A Contemporary Classic: Foster by Claire Keegan (#NovNov22)

This year for Novellas in November, Cathy and I chose to host one overall buddy read, Foster by Claire Keegan. I ended up reviewing it for BookBrowse. My full review is here and I also wrote a short related article on Keegan’s career and the unusual publishing history of this particular novella. Here are short excerpts from both:

Claire Keegan’s delicate, heart-rending novella tells the story of a deprived young Irish girl sent to live with rural relatives for one pivotal summer. Although Foster feels like a timeless fable, a brief mention of IRA hunger strikers dates it to 1981. It bears all the hallmarks of a book several times its length: a convincing and original voice, rich character development, an evocative setting, just enough backstory, psychological depth, conflict and sensitive treatment of difficult themes like poverty and neglect. I finished the one-sitting read in a flood of tears, hoping the Kinsellas’ care might be enough to protect the girl from the harshness she may face in the rest of her growing-up years. Keegan unfolds a cautionary tale of endangered childhood, also hinting at the enduring difference a little compassion can make. [128 pages]

Foster is now in print for the first time in the USA (from Grove Atlantic), having had an unusual path to publication. It first appeared in the New Yorker in 2010, but in abridged form. Keegan told the Guardian she felt the condensed version “was very well done but wasn’t the whole story. It had some of the layers taken out, but I think the heart was the same.” She herself has described Foster as a long short story; “It is definitely not a novella. It doesn’t have the pace of a novella.” Faber & Faber first published it as a standalone volume in the UK in 2010. A 2022 Irish-language film version of Foster, called The Quiet Girl (which names the main character Cait) became a favorite on the international film festival circuit.

Foster is now in print for the first time in the USA (from Grove Atlantic), having had an unusual path to publication. It first appeared in the New Yorker in 2010, but in abridged form. Keegan told the Guardian she felt the condensed version “was very well done but wasn’t the whole story. It had some of the layers taken out, but I think the heart was the same.” She herself has described Foster as a long short story; “It is definitely not a novella. It doesn’t have the pace of a novella.” Faber & Faber first published it as a standalone volume in the UK in 2010. A 2022 Irish-language film version of Foster, called The Quiet Girl (which names the main character Cait) became a favorite on the international film festival circuit.

[Edited on December 1st]

A number of you joined us in reading Foster this month:

Lynne at Fictionophile

Karen at The Simply Blog

Davida at The Chocolate Lady’s Book Reviews

Tony at Tony’s Book World

Brona at This Reading Life

Janet at Love Books Read Books

Jane at Just Reading a Book

Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best

Carol at Reading Ladies

(Cathy also reviewed it last year.)

Our bloggers have been impressed with the spare, precise writing style and the emotional heft of this little tale. Their only complaint? The slight ambiguity of the ending. Read it yourself to find out what you think! If you’d still like to take part in the buddy read and have an hour or two free, remember you can access the original version of the story here.

Two for #NovNov22 and #NonFicNov: Recipe and Shameless

Contrary to my usual habit of leaving new books on the shelf for years before actually reading them, these two are ones I just got as birthday gifts last month. They were great choices from my wish list from my best friend and reflect our mutual interests (foodie lit) and experiences (ex-Evangelicals raised in the Church).

Recipe by Lynn Z. Bloom (2022)

This is part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series of short nonfiction works (I’ve only read a few of the other releases, but I’d also recommend Fat by Hanne Blank). Bloom, an esteemed academic based in Connecticut, envisions a recipe as being like a jazz piece: it arises from a clear tradition, yet offers a lot of scope for creativity and improvisation.

A recipe is a paradoxical construct, a set of directions that specify precision but—baking excepted—anticipate latitude. A recipe is an introduction to the logic of a dish, a scaffold bringing order to the often casual process of making it.

A recipe supplies the bridge between hope and fulfilment, for a recipe offers innumerable opportunities to review, revise, adapt, and improve, to make the dish the cook’s and eater’s own.

She considers the typical recipe template, the spread of international dishes, how particular chefs incorporate stories in their cookbooks, and the role that food plays in celebrations. To illustrate her points, she traces patterns via various go-to recipes: for chicken noodle soup, crepes, green salad, mac and cheese, porridge, and melting-middle chocolate pots.

She considers the typical recipe template, the spread of international dishes, how particular chefs incorporate stories in their cookbooks, and the role that food plays in celebrations. To illustrate her points, she traces patterns via various go-to recipes: for chicken noodle soup, crepes, green salad, mac and cheese, porridge, and melting-middle chocolate pots.

I most enjoyed the sections on comfort food (“a platterful of stability in a turbulent, ever-changing world beset by traumas and tribulations”) and Thanksgiving – coming up on Thursday for Americans. Best piece of trivia: in 1909, President Taft, known for being a big guy, served a 26-pound opossum as well as a 30-pound turkey for the White House holiday dinner. (Who knew possums came that big?!)

Bloom also has a social conscience: in Chapters 5 and 6, she writes about the issues of food insecurity, and child labour in the chocolate production process. As important as these are to draw attention to, it did feel like these sections take away from the main focus of the book. Recipe also feels like it was hurriedly put together – with more typos than I’m used to seeing in a published work. Still, it was an engaging read. [136 pages]

Shameless: A Sexual Reformation by Nadia Bolz-Weber (2019)

“Shame is the lie someone told you about yourself.” ~Anaïs Nin

Bolz-Weber, founding Lutheran pastor of House for All Sinners and Saints in Denver, Colorado, was a mainstay on the speaker programme at Greenbelt Festival in the years I attended. Her main arguments here: people matter more than doctrines, sex (like alcohol, food, work, and anything else that can become the object of addiction) is morally neutral, and Evangelical/Religious Right teachings on sexuality are not biblical.

She believes that purity culture – familiar to any Church kid of my era – did a whole generation a disservice; that teaching young people to view sex as amazing-but-deadly unless you’re a) cis-het and b) married led instead to “a culture of secrecy, hypocrisy, and double standards.”

She believes that purity culture – familiar to any Church kid of my era – did a whole generation a disservice; that teaching young people to view sex as amazing-but-deadly unless you’re a) cis-het and b) married led instead to “a culture of secrecy, hypocrisy, and double standards.”

Purity most often leads to pride or to despair, not to holiness. … Holiness happens when we are integrated as physical, spiritual, sexual, emotional, and political beings.

A number of chapters are built around anecdotes about her parishioners, many of them queer or trans, and about her own life. “The Rocking Chair” is an excellent essay about her experience of pregnancy and parenthood, which includes having an abortion at age 24 before later becoming a mother of two. She knows she would have loved that baby, yet she doesn’t regret her choice at all. She was not ready.

This chapter is followed by an explanation of how abortion became the issue for the political right wing in the USA. Spoiler alert: it had nothing to do with morality; it was all about increasing the voter base. In most Judeo-Christian theology prior to the 1970s, by contrast, it was believed that life started with breath (i.e., at birth, rather than at conception, as the pro-life lobby contends). In other between-chapter asides, she retells the Creation story and proffers an alternative to the Nashville Statement on marriage and gender roles.

Bolz-Weber is a real badass, but it’s not just bravado: she has the scriptures to back it all up. This was a beautiful and freeing book. [198 pages]

The Heart of Things by Richard Holloway (#NovNov22 Nonfiction Week)

This was my sixth book by Holloway, a retired Bishop of Edinburgh whose perspective is maybe not what you would expect from a churchman – he focuses on this life and on practical and emotional needs rather than on the supernatural or abstruse points of theology. His recent work, such as Waiting for the Last Bus, also embraces melancholy in a way that many on the more evangelical end of Christianity might deem shamefully negative.

Being a pessimist myself, though, I find that his outlook resonates. The title of this 2021 release, originally subtitled “An Anthology of Memory and Regret,” comes from Virgil’s Aeneid (“there are tears at the heart of things [sunt lacrimae rerum]”), and that context makes it clearer where he’s coming from. In the same paragraph in which he reveals that source, he defines melancholia as “sorrowing empathy for the constant defeats of the human condition.”

Being a pessimist myself, though, I find that his outlook resonates. The title of this 2021 release, originally subtitled “An Anthology of Memory and Regret,” comes from Virgil’s Aeneid (“there are tears at the heart of things [sunt lacrimae rerum]”), and that context makes it clearer where he’s coming from. In the same paragraph in which he reveals that source, he defines melancholia as “sorrowing empathy for the constant defeats of the human condition.”

The book is in six thematic essays that plait Holloway’s own thoughts with lengthy quotations, especially from 19th- and 20th-century poetry: Passing – Mourning – Warring – Ruining – Regretting – Forgiving. The war chapter, though appropriate for it having just been Remembrance Day, engaged me the least, while the section on ruin sticks closely to the author’s Glasgow childhood and so seems to offer less universal value than the rest. I most appreciated the first two chapters and the one on regret, which features musings on Nietzsche’s “amor fati” and extended quotes from Borges, Housman and MacNeice.

We melancholics are prone to looking backwards, even when we know it’s not good for us; to dwelling on our losses and failures. The final chapter, then, is key, insisting on self-forgiveness because of the forgiveness modelled by Christ (in whatever way you understand that). Holloway believes in the edifying wisdom of poetry, which he calls “greater than the intention of its makers and [continuing] to reveal new meanings long after they are gone.” He’s created an unusual and pensive collection that will perform the same role.

[147 pages]

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

#NovNov22 Nonfiction Week Begins! with Strangers on a Pier by Tash Aw

Short nonfiction week of Novellas in November is (not so) secretly my favourite theme of this annual challenge. About 40% of my reading is nonfiction, and I love finding books that illuminate a topic or a slice of life in well under 200 pages. I’ll see if I can review one per day this week.

Back in 2013 I read Tash Aw’s Booker-longlisted Five Star Billionaire and thought it was a fantastic novel about strangers thrown together in contemporary Shanghai. I don’t know why it hadn’t occurred to me to find something else by him in the meantime, but when I spotted this slim volume up in the library’s biography section, I knew it had to come home with me.

Originally published in the USA as The Face in 2016, this is a brief family memoir reflecting on migration and belonging. Aw was born in Taiwan and grew up in Malaysia in an ethnically Chinese family; wherever he goes, he can pass as any number of Asian ethnicities. Both of his grandfathers were Chinese immigrants to Malaysia, but from different regions and speaking separate dialects. (This is something those of us in the West unfamiliar with China can struggle to understand: it has no monolithic identity or language. The food and culture might vary as much by region as they do in, say, different countries of Europe.)

Originally published in the USA as The Face in 2016, this is a brief family memoir reflecting on migration and belonging. Aw was born in Taiwan and grew up in Malaysia in an ethnically Chinese family; wherever he goes, he can pass as any number of Asian ethnicities. Both of his grandfathers were Chinese immigrants to Malaysia, but from different regions and speaking separate dialects. (This is something those of us in the West unfamiliar with China can struggle to understand: it has no monolithic identity or language. The food and culture might vary as much by region as they do in, say, different countries of Europe.)

Aw imagines his ancestors’ arrival and the disorientation they must have known as they made their way to an address on a piece of paper. His family members never spoke about their experiences, but the sense of being an outsider, a minority is something that has recurred through their history. Aw himself felt it keenly as a university student in Britain.

After the first long essay, “The Face,” comes a second, “Swee Ee, or Eternity,” addressed in the second person to his late grandmother, about whom, despite having worked in her shop as a boy, he knew next to nothing before he spent time with her as she was dying of cancer.

When is short nonfiction too short? Well, I feel that what I just read was actually two extended magazine articles rather than a complete book – that I read a couple of stories rather than the whole story. Perhaps that is inevitable for such a short autobiographical work, though I can think of two previous memoirs from last year alone that managed to be comprehensive, self-contained and concise: The Story of My Life by Helen Keller and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy. (Public library)

[91 pages]

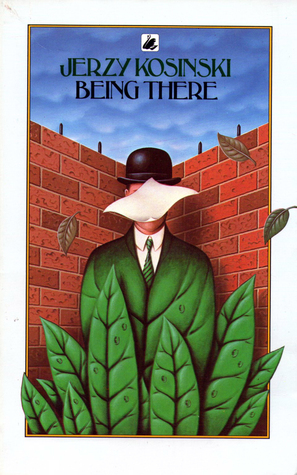

Being There by Jerzy Kosiński (#NovNov22 Short Classics Week)

I knew pretty much nothing about this when I went into it and that was for the best. Only after I’d finished reading it (in one sitting) did I remember that there’s a Peter Sellers film; I’m glad I wasn’t imagining him in my head the whole time.

If you keep in mind that this is a satire on certain American qualities – gullibility, the obsession with money and appearance – you can probably, like I did, excuse the thinness of the plot, the clichéd behaviour of the characters, and the sometimes dated feel (this is from 1970).

Chance is an utter innocent, an illiterate orphan; his whole history is a blank. Most of what he knows comes from television, which he watches devotedly. He lives in one half of a house; the Old Man in the other. Apart from one maid or another, he sees no one else and has never left the complex for any reason. Aside from TV, his only hobby is gardening. The house’s walled garden is his haven and his joy. When the Old Man dies, the lawyers can find no record of a hired gardener or other retainer so Chance, like Adam, is cast out of his Eden and into … suburban New York City. Where he’s promptly hit by a limo, then taken to recuperate at the home of the rich businessman’s wife who was riding in it, Elizabeth Eve (or EE) Rand.

Chance is an utter innocent, an illiterate orphan; his whole history is a blank. Most of what he knows comes from television, which he watches devotedly. He lives in one half of a house; the Old Man in the other. Apart from one maid or another, he sees no one else and has never left the complex for any reason. Aside from TV, his only hobby is gardening. The house’s walled garden is his haven and his joy. When the Old Man dies, the lawyers can find no record of a hired gardener or other retainer so Chance, like Adam, is cast out of his Eden and into … suburban New York City. Where he’s promptly hit by a limo, then taken to recuperate at the home of the rich businessman’s wife who was riding in it, Elizabeth Eve (or EE) Rand.

With his gardening stories that everyone takes to be metaphorical, Chase soon wins over Wall Street and White House alike, and fields propositions from men and women just the same. He takes his cues for how to act in social situations from his extensive mental archive of TV programs. It all gets a bit silly, but the naïf at the heart of it is so sweet that I didn’t mind. He’s like Forrest Gump or any number of other simple characters who get drawn into current events (it seems like quite the Hollywood trope, in fact); just by going along with what people assume about him, he comes across as intelligent and wise. His name can’t be coincidental, with its connotations of risk, fate, or just seizing opportunities. Luckily, the satire doesn’t outstay its welcome. However, I felt that the book just stops, with no proper ending.

(Kosiński’s life story is its own stranger-than-fiction tale; the biographical essay in the back of my paperback is only about five pages long but there were many points where I wondered if it was a tongue-in-cheek appendix! The novella is autobiographical, it seems, in that the author was married to a rich American widow and moved in the kind of wealthy circles the Rands do.)

[105 pages] (Secondhand purchase)

Up at the Villa by W. Somerset Maugham (#NovNov22 Short Classics Week)

This was just what I want from a one-sitting read: surprising and satisfying, and in this case with enough suspense to keep the pages turning. When beautiful 30-year-old widow Mary Panton, staying in a villa in the hills overlooking Florence, receives two marriage proposals within the first 33 pages, I worried I was in for a boring, conventional story.

However, things soon get much more interesting. Her suitors are Sir Edgar Swift of the Indian Civil Service, 24 years her senior and just offered a job as the governor of Bengal; and Rowley Flint, a notorious lady’s man. Edgar has to go away on business and will ask for her answer when he’s back in several days. He leaves her with a revolver to take with her if she goes out in the car. A Chekhov’s gun? Absolutely. And it’ll be up to Mary and Rowley to deal with the consequences.

However, things soon get much more interesting. Her suitors are Sir Edgar Swift of the Indian Civil Service, 24 years her senior and just offered a job as the governor of Bengal; and Rowley Flint, a notorious lady’s man. Edgar has to go away on business and will ask for her answer when he’s back in several days. He leaves her with a revolver to take with her if she goes out in the car. A Chekhov’s gun? Absolutely. And it’ll be up to Mary and Rowley to deal with the consequences.

I’ll avoid further details; it’s too much fun to discover those for yourself. I’ll just mention that some intriguing issues get brought in, such as political dissidence in the early days of WWII, charity vs. pity, and the double standard of promiscuity in men vs. women.

Compared to something like Of Human Bondage, sure, this 1941 novella is a minor work, but I found it hugely enjoyable and would recommend it to anyone looking for a short classic or wanting to try Maugham (from here advance to The Painted Veil and The Moon and Sixpence before trying one of the chunksters).

Some plot points are curiously similar to Downton Abbey seasons 1–3, leading me to wonder if this was actually a conscious or unconscious influence on Julian Fellowes. Mostly, though, this reminded me of The Talented Mr. Ripley. It’s a deliciously twisted little book where you find yourself rooting for people you might not sympathize with in real life.

And how’s this for a last line? “Darling, that’s what life’s for – to take risks.”

(See also Simon’s review.)

[120 pages] (Public library)

We Have Always Lived in the Castle (#NovNov22 Short Classics Week)

Novellas in November is here! Our first weekly theme is short classics. (Leave your links with Cathy, here.)

Left over from a planned second R.I.P. post that I didn’t get a chance to finish:

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson (1962)

A few years ago for the R.I.P. challenge I read The Haunting of Hill House, which is a terrific haunted house/horror novel, a genre I almost never read. I was expecting this to be more of the same from Jackson, but instead it’s a brooding character study of two sisters isolated by their scandalous family history and the suspicion of the townspeople. Narrator Merricat (Mary Katherine Blackwood) tells us in the first paragraph that she is 18, but she sounds and acts more like a half-feral child of 10 who makes shelters in the woods for her and her cat Jonas; I wasn’t sure if I should understand her to be intellectually disabled, or willfully childish, or some combination thereof.

A few years ago for the R.I.P. challenge I read The Haunting of Hill House, which is a terrific haunted house/horror novel, a genre I almost never read. I was expecting this to be more of the same from Jackson, but instead it’s a brooding character study of two sisters isolated by their scandalous family history and the suspicion of the townspeople. Narrator Merricat (Mary Katherine Blackwood) tells us in the first paragraph that she is 18, but she sounds and acts more like a half-feral child of 10 who makes shelters in the woods for her and her cat Jonas; I wasn’t sure if I should understand her to be intellectually disabled, or willfully childish, or some combination thereof.

Her older sister Constance does everything for her and for wheelchair-bound Uncle Julian, the only family they have left after most of their relatives died of poisoning six years ago. Constance stood trial for their murder and was acquitted, but the locals haven’t let the incident go and even chant a cruel rhyme whenever Merricat comes into town for shopping: “Merricat, said Connie, would you like a cup of tea? / Oh, no, said Merricat, you’ll poison me.” Julian obsessively mulls over the details of the poisoning, building a sort of personal archive of tragedy, while in everyday life a curtain of dementia separates him from reality. When cousin Charles comes to visit, perhaps to get a share of the money they have hidden around the place, he threatens the idyll they’ve created, and Merricat starts joking about poisonous mushrooms…

I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

Joyce Carol Oates’s afterword brings up an interesting point about how food is fetishized in Jackson’s fiction – I look forward to trying more of it. (Public library)

Need some more ideas of short classics? Here’s a list of favourites I posted a couple of years ago, and a Book Riot list with only a couple of overlaps.

This month I also hope to have a look through Great Short Books by Kenneth C. Davis, a selection of 58 classic and contemporary works (some of them perhaps a bit longer than our cutoff of 200 pages). It’s forthcoming from Scribner on the 22nd, but I have an e-copy via Edelweiss that I will skim.

This month I also hope to have a look through Great Short Books by Kenneth C. Davis, a selection of 58 classic and contemporary works (some of them perhaps a bit longer than our cutoff of 200 pages). It’s forthcoming from Scribner on the 22nd, but I have an e-copy via Edelweiss that I will skim.

Novellas in November: A Change of Plans

I will be leaving Novellas in November in Cathy’s very capable hands this year. From tomorrow there will be a pinned post on her blog, 746 Books, where you can leave your links throughout the month.

We lost my mother yesterday evening, suddenly, and I’ll be flying out to the States in the next couple of days to help with arrangements and attend the funeral.

I happen to have read a few novellas already so will schedule in reviews of those, but won’t be able to read or write as much as I’d like. I might not manage to reply to comments or keep up with social media and your own blogs – forgive me.

I’ll be taking plenty of books with me, including lots of novellas. Perfect for travel days and moments stolen away from tedious admin tasks. And (books in general, of course) for distraction, comfort and good cheer. One thing I was sure to mention in the obituary I wrote this morning was that my mother passed on to me and to her many students her great love of reading.

This short memoir could have fit next week’s nonfiction focus, but because it is translated from the Hebrew I’ve chosen to use it to round off our literature in translation week. Poet Anat Levit didn’t start off as a cat lady, yet in the year following her divorce she adopted five kittens. The first, Shelly, was a present for her small daughters, Daphna and Shlomit, and then another four fluffballs tempted her at the pet store: Afro, Lady, Mocha and Jesse. Add on Cleo, a beautiful Siamese she bought on impulse from a neighbour, and Mishely, a local stray she started to look after, and there you have it: the seven cats who took over her life.

This short memoir could have fit next week’s nonfiction focus, but because it is translated from the Hebrew I’ve chosen to use it to round off our literature in translation week. Poet Anat Levit didn’t start off as a cat lady, yet in the year following her divorce she adopted five kittens. The first, Shelly, was a present for her small daughters, Daphna and Shlomit, and then another four fluffballs tempted her at the pet store: Afro, Lady, Mocha and Jesse. Add on Cleo, a beautiful Siamese she bought on impulse from a neighbour, and Mishely, a local stray she started to look after, and there you have it: the seven cats who took over her life. Rather like a linked short story collection, it presents vignettes from the lives of two female artists – Mari, a writer and illustrator; and Jonna, a visual artist and filmmaker – who are long-term, devoted partners. Of course, this cannot be read as other than autobiographical of Jansson and her partner of 45 years, Tuulikki Pietilä. There are other specific details drawn from life, too.

Rather like a linked short story collection, it presents vignettes from the lives of two female artists – Mari, a writer and illustrator; and Jonna, a visual artist and filmmaker – who are long-term, devoted partners. Of course, this cannot be read as other than autobiographical of Jansson and her partner of 45 years, Tuulikki Pietilä. There are other specific details drawn from life, too. This potted biography of the author best known for the Moomins showcases the development of her artistic style and literary themes. Born at the start of World War I into a family of artists (her father a sculptor, her mother a graphic designer, her brother Lars a collaborator on her comics), Jansson wanted to paint but had limited opportunities as a woman. The book contains a wealth of illustrations – over 100, so nearly one per page – including photographs and high-quality reproductions, many in color and some in black and white, of Jansson’s comics, paintings and book covers. Gravett also probes the autobiographical influences on Jansson’s work, which are particularly clear in her 15 books for adults. A sensitive portrayal of Finland’s most widely translated author, this is itself a work of art.

This potted biography of the author best known for the Moomins showcases the development of her artistic style and literary themes. Born at the start of World War I into a family of artists (her father a sculptor, her mother a graphic designer, her brother Lars a collaborator on her comics), Jansson wanted to paint but had limited opportunities as a woman. The book contains a wealth of illustrations – over 100, so nearly one per page – including photographs and high-quality reproductions, many in color and some in black and white, of Jansson’s comics, paintings and book covers. Gravett also probes the autobiographical influences on Jansson’s work, which are particularly clear in her 15 books for adults. A sensitive portrayal of Finland’s most widely translated author, this is itself a work of art.