#NonFicNov: Being the Expert on Covid Diaries

This year the Be/Ask/Become the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Veronica of The Thousand Book Project. (In previous years I’ve contributed lists of women’s religious memoirs (twice), accounts of postpartum depression, and books on “care”.)

I’ve been devouring nonfiction responses to COVID-19 for over a year now. Even memoirs that are not specifically structured as diaries take pains to give a sense of what life was like from day to day during the early months of the pandemic, including the fear of infection and the experience of lockdown. Covid is mentioned in lots of new releases these days, fiction or nonfiction, even if just via an introduction or epilogue, but I’ve focused on books where it’s a major element. At the end of the post I list others I’ve read on the theme, but first I feature four recent releases that I was sent for review.

Year of Plagues: A Memoir of 2020 by Fred D’Aguiar

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

Cancer needs a song: tambourine and cymbals and a choir, not to raise it from the dead but [to] lay it to rest finally.

Tracing the effects of his cancer on his wife and children as well as on his own body, he wonders if the treatment will disrupt his sense of his own masculinity. I thought the narrative would hit home given that I have a family member going through the same thing, but it struck me as a jumble, full of repetition and TMI moments. Expecting concision from a poet, I wanted the highlights reel instead of 323 rambling pages.

(Carcanet Press, August 26.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Still, I appreciated Josipovici’s thoughts on literature and his own aims for his work (more so than the rehashing of Covid statistics and official briefings from Boris Johnson et al., almost unbearable to encounter again):

In my writing I have always eschewed visual descriptions, perhaps because I don’t have a strong visual memory myself, but actually it is because reading such descriptions in other people’s novels I am instantly bored and feel it is so much dead wood.

nearly all my books and stories try to force the reader (and, I suppose, as I wrote, to force me) to face the strange phenomenon that everything does indeed pass, and that one day, perhaps sooner than most people think, humanity will pass and, eventually, the universe, but that most of the time we live as though all was permanent, including ourselves. What rich soil for the artist!

Why have I always had such an aversion to first person narratives? I think precisely because of their dishonesty – they start from a falsehood and can never recover. The falsehood that ‘I’ can talk in such detail and so smoothly about what has ‘happened’ to ‘me’, or even, sometimes, what is actually happening as ‘I’ write.

You never know till you’ve plunged in just what it is you really want to write. When I started writing The Inventory I had no idea repetition would play such an important role in it. And so it has been all through, right up to The Cemetery in Barnes. If I was a poet I would no doubt use refrains – I love the way the same thing becomes different the second time round

To write a novel in which nothing happens and yet everything happens: a secret dream of mine ever since I began to write

I did sense some misogyny, though, as it’s generally female writers he singles out for criticism: Iris Murdoch is his prime example of the overuse of adjectives and adverbs, he mentions a “dreadful novel” he’s reading by Elizabeth Bowen, and he describes Jean Rhys and Dorothy Whipple as women “who, raised on a diet of the classic English novel, howled with anguish when life did not, for them, turn out as they felt it should.”

While this was enjoyable to flip through, it’s probably more for existing fans than for readers new to the author’s work, and the Covid connection isn’t integral to the writing experiment.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

A stanza from the below collection to link the first two books to this next one:

Have they found him yet, I wonder,

whoever it is strolling

about as a plague doctor, outlandish

beak and all?

The Crash Wake and Other Poems by Owen Lowery

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

As the seventh anniversary of his wedding to Jayne nears, Lowery reflects on how love has kept him going despite flashbacks to the accident and feeling written off by his doctors. In the second section of the book, the subjects vary from the arts (Paula Rego’s photographs, Stanley Spencer’s paintings, R.S. Thomas’s theology) to sport. There is also a lovely “Remembrance Day Sequence” imagining what various soldiers, including Edward Thomas and his own grandfather, lived through. The final piece is a prose horror story about a magpie. Like a magpie, I found many sparkly gems in this wide-ranging collection.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free e-copy for review.

Behind the Mask: Living Alone in the Epicenter by Kate Walter

[135 pages, so I’m counting this one towards #NovNov, too]

For Walter, a freelance journalist and longtime Manhattan resident, coronavirus turned life upside down. Retired from college teaching and living in Westbeth Artists Housing, she’d relied on activities outside the home for socializing. To a single extrovert, lockdown offered no benefits; she spent holidays alone instead of with her large Irish Catholic family. Even one of the world’s great cities could be a site of boredom and isolation. Still, she gamely moved her hobbies onto Zoom as much as possible, and welcomed an escape to Jersey Shore.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

There’s a lot here to relate to – being glued to the news, anxiety over Trump’s possible re-election, looking forward to vaccination appointments – and the book is also revealing on the special challenges for older people and those who don’t live with family. However, I found the whole fairly repetitive (perhaps as a result of some pieces originally appearing in The Village Sun and then being tweaked and inserted here).

Before an appendix of four short pre-Covid essays, there’s a section of pandemic writing prompts: 12 sets of questions to use to think through the last year and a half and what it’s meant. E.g. “Did living through this extraordinary experience change your outlook on life?” If you’ve been meaning to leave a written record of this time for posterity, this list would be a great place to start.

(Heliotrope Books, November 16.) With thanks to the publicist for the free e-copy for review.

Other Covid-themed nonfiction I have read:

Medical accounts

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

- Intensive Care by Gavin Francis

- Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer and Dan Koeppel (reviewed for Shelf Awareness)

- Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta

- Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

+ I have a proof copy of Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki, coming out in January.

Nature writing

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

- The Heeding by Rob Cowen (in poetry form)

- Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt

- The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

- Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss

General responses

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

- The Rome Plague Diaries by Matthew Kneale

- Quarantine Comix by Rachael Smith (in graphic novel form; reviewed for Foreword Reviews)

- UnPresidented by Jon Sopel

+ on my Kindle: Alone Together, an anthology of personal essays

+ on my TBR: What Just Happened: Notes on a Long Year by Charles Finch

If you read just one… Make it Intensive Care by Gavin Francis. (And, if you love nature books, follow that up with The Consolation of Nature.)

Can you see yourself reading any of these?

The Fell by Sarah Moss for #NovNov

Sarah Moss’s latest three releases have all been of novella length. I reviewed Ghost Wall for Novellas in November in 2018, and Summerwater in August 2020. In this trio, she’s demonstrated a fascination with what happens when people of diverging backgrounds and opinions are thrown together in extreme circumstances. Moss almost stops time as her effortless third-person omniscient narration moves from one character’s head to another. We feel that we know each one’s experiences and motivations from the inside. Whereas Ghost Wall was set in two weeks of a late-1980s summer, Summerwater and now the taut The Fell have pushed that time compression even further, spanning a day and about half a day, respectively.

A circadian narrative holds a lot of appeal – we’re all tantalized, I think, by the potential difference that one day can make. The particular day chosen as the backdrop for The Fell offers an ideal combination of the mundane and the climactic because it was during the UK’s November 2020 lockdown. On top of that blanket restriction, single mum Kate has been exposed to Covid-19 via a café colleague, so she and her teenage son Matt are meant to be in strict two-week quarantine. Except Kate can’t bear to be cooped up one minute longer and, as dusk falls, she sneaks out of their home in the Peak District National Park to climb a nearby hill. She knows this fell like the back of her hand, so doesn’t bother taking her phone.

Over the next 12 hours or so, we dart between four stream-of-consciousness internal monologues: besides Kate and Matt, the two main characters are their neighbour, Alice, an older widow who has undergone cancer treatment; and Rob, part of the volunteer hill rescue crew sent out to find Kate when she fails to return quickly. For the most part – as befits the lockdown – each is stuck in their solitary musings (Kate regrets her marriage, Alice reflects on a bristly relationship with her daughter, Rob remembers a friend who died up a mountain), but there are also a few brief interactions between them. I particularly enjoyed time spent with Kate as she sings religious songs and imagines a raven conducting her inquisition.

What Moss wants to do here, is done well. My misgiving is to do with the recycling of an identical approach from Summerwater – not just the circadian limit, present tense, no speech marks and POV-hopping, but also naming each short chapter after a random phrase from it. Another problem is one of timing. Had this come out last November, or even this January, it might have been close enough to events to be essential. Instead, it seems stuck in a time warp. Early on in the first lockdown, when our local arts venue’s open mic nights had gone online, one participant made a semi-professional music video for a song with the refrain “everyone’s got the same jokes.”

That’s how I reacted to The Fell: baking bread and biscuits, a family catch-up on Zoom, repainting and clearouts, even obsessive hand-washing … the references were worn out well before a draft was finished. Ironic though it may seem, I feel like I’ve found more cogent commentary about our present moment from Moss’s historical work. Yet I’ve read all of her fiction and would still list her among my favourite contemporary writers. Aspiring creative writers could approach the Summerwater/The Fell duology as a masterclass in perspective, voice and concise plotting. But I hope for something new from her next book.

[180 pages]

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Other reviews:

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (#NovNov Nonfiction Buddy Read)

For nonfiction week of Novellas in November, our buddy read is The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (1903). You can download the book for free from Project Gutenberg here if you’d still like to join in.

Keller’s story is culturally familiar to us, perhaps from the William Gibson play The Miracle Worker, but I’d never read her own words. She was born in Alabama in 1880; her father had been a captain in the Confederate Army. An illness (presumed to be scarlet fever) left her blind and deaf at the age of 19 months, and she describes herself in those early years as mischievous and hot-tempered, always frustrated at her inability to express herself. The arrival of her teacher, Anne Sullivan, when Helen was six years old transformed her “silent, aimless, dayless life.”

I was fascinated by the glimpses into child development and education. Especially after she learned Braille, Keller loved books, but she believed she learned just as much from nature: “everything that could hum or buzz, or sing, or bloom, had a part in my education.” She loved to sit in the family orchard and would hold insects or fossils and track plant and tadpole growth. Her first trip to the ocean (Chapter 10) was a revelation, and rowing and sailing became two of her chief hobbies, along with cycling and going to the theatre and museums.

At age 10 Keller relearned to speak – a more efficient way to communicate than her usual finger-spelling. She spent winters in Boston and eventually attended the Cambridge School for Young Ladies in preparation for starting college at Radcliffe. Her achievements are all the more remarkable when you consider that smell and touch – senses we tend to overlook – were her primary ones. While she used a typewriter to produce schoolwork, a teacher spelling into her hand was still her main way to intake knowledge. Specialist textbooks for mathematics and multiple languages were generally not available in Braille. Digesting a lesson and completing homework thus took her much longer than it did her classmates, but still she felt “impelled … to try my strength by the standards of those who see and hear.”

It was surprising to find, at the center of the book, a detailed account of a case of unwitting plagiarism (Chapter 14). Eleven-year-old Keller wrote a story called “The Frost King” for a beloved teacher at the Perkins Institution for the Blind. He was so pleased that he printed it in one of their publications, but it soon came to his attention that the plot was very similar to “The Frost Fairies” in Birdie and His Friends by Margaret T. Canby. The tale must have been read to Keller long ago but become so deeply buried in the compost of a mind’s memories that she couldn’t recall its source. Some accused Keller and Sullivan of conspiring, and this mistrust more than the incident itself cast a shadow over her life for years to come. I was impressed by Keller discussing in depth something that it would surely have been more comfortable to bury. (I’ve sometimes had the passing thought that if I wrote a memoir I would structure it around my regrets or most embarrassing moments. Would that be penance or masochism?)

This short memoir was first serialized in the Ladies’ Home Journal. Keller was only 23 and partway through her college degree at the time of publication. An initial chronological structure later turns more thematic and the topics are perhaps a little scattershot. I would attribute this, at least in part, to the method of composition: it would be difficult to make large-scale edits on a manuscript because everything she typed had to be spelled back to her for approval. Minor line edits would be easy enough, but not big structural changes. (I wonder if it’s similar with work that’s been dictated, like May Sarton’s later journals.)

Helen Keller in graduation cap and gown. (PPOC, Library of Congress. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Keller went on to write 12 more books. It would be interesting to follow up with another one to learn about her travels and philanthropic work. For insight into a different aspect of her life – bearing in mind that it’s fiction – I recommend Helen Keller in Love by Rosie Sultan. In a couple of places Keller mentions Laura Bridgman, her less famous predecessor in the deaf–blind community; Kimberly Elkins’ 2014 What Is Visible is a stunning novel about Bridgman.

For such a concise book – running to just 75 pages in my Dover Thrift Editions paperback – this packs in so much. Indeed, I’ve found more to talk about in this review than I might have expected. The elements that most intrigued me were her early learning about abstractions like love and thought, and her enthusiastic rundown of her favorite books: “In a word, literature is my Utopia. Here I am not disenfranchised. No barrier of the senses shuts me out from the sweet, gracious discourse of my book-friends.”

It’s possible some readers will find her writing style old-fashioned. It would be hard to forget you’re reading a work from nearly 120 years ago, given the sentimentality and religious metaphors. But the book moves briskly between anecdotes, with no filler. I remained absorbed in Keller’s story throughout, and so admired her determination to obtain a quality education. I know we’re not supposed to refer to disabled authors’ work as “inspirational,” so instead I’ll call it both humbling and invigorating – a reminder of my privilege and of the force of the human will. (Secondhand purchase, Barter Books)

Also reviewed by:

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Short Nature Books for #NovNov by John Burnside, Jim Crumley and Aimee Nezhukumatathil

#NovNov meets #NonfictionNovember as nonfiction week of Novellas in November continues!

Tomorrow I’ll post my review of our buddy read for the week, The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free from Project Gutenberg, here).

Today I review four nature books that celebrate marvelous but threatened creatures and ponder our place in relation to them.

Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction by John Burnside (2021)

[127 pages]

I’ve read a novel, a memoir, and several poetry collections by Burnside. He’s a multitalented author who’s written in many different genres. These four essays are rich with allusions and chewy with philosophical questions. “Aurochs” traces ancient bulls from the classical world onward and notes the impossibility of entering others’ subjectivity – true for other humans, so how much more so for extinct animals. Imagination and empathy are required. Burnside recounts an incident from when he went to visit his former partner’s family cattle farm in Gloucestershire and a poorly cow fell against his legs. Sad as he felt for her, he couldn’t help.

I’ve read a novel, a memoir, and several poetry collections by Burnside. He’s a multitalented author who’s written in many different genres. These four essays are rich with allusions and chewy with philosophical questions. “Aurochs” traces ancient bulls from the classical world onward and notes the impossibility of entering others’ subjectivity – true for other humans, so how much more so for extinct animals. Imagination and empathy are required. Burnside recounts an incident from when he went to visit his former partner’s family cattle farm in Gloucestershire and a poorly cow fell against his legs. Sad as he felt for her, he couldn’t help.

“Auks” tells the story of how we drove the Great Auk to extinction and likens it to whaling, two tragic cases of exploiting species for our own ends. The second and fourth essays stood out most to me. “The hint half guessed, the gift half understood” links literal species extinction with the loss of a sense of place. The notion of ‘property’ means that land becomes a space to be filled. Contrast this with places devoid of time and ownership, like Chernobyl. Although I appreciated the discussion of solastalgia and ecological grief, much of the material here felt a rehashing of my other reading, such as Footprints, Islands of Abandonment, Irreplaceable, Losing Eden and Notes from an Apocalypse. Some Covid references date this one in an unfortunate way, while the final essay, “Blossom Ruins,” has a good reason for mentioning Covid-19: Burnside was hospitalized for it in April 2020, his near-death experience a further spur to contemplate extinction and false hope.

The academic register and frequent long quotations from other thinkers may give other readers pause. Those less familiar with current environmental nonfiction will probably get more out of these essays than I did, though overall I found them worth engaging with.

With thanks to Little Toller Books for the proof copy for review.

Kingfisher and Otter by Jim Crumley (2018)

[59 pages each]

Part of Crumley’s “Encounters in the Wild” series for the publisher Saraband, these are attractive wee hardbacks with covers by Carry Akroyd. (I’ve previously reviewed his The Company of Swans.) Each is based on the Scottish nature writer’s observations and serendipitous meetings, while an afterword gives additional information on the animal and its appearances in legend and literature.

An unexpected link between these two volumes was beavers, now thriving in Scotland after a recent reintroduction. Crumley marvels that, 400 years after their kind could last have interacted with beavers, otters have quickly gotten used to sharing rivers – to him this “suggests that race memory is indestructible.” Likewise, kingfishers gravitate to where beaver dams have created fish-filled ponds.

Kingfisher was, marginally, my preferred title from the pair. It sticks close to one spot, a particular “bend in the river” where the author watches faithfully and is occasionally rewarded by the sight of one or two kingfishers. As the book opens, he sees what at first looks like a small brown bird flying straight at him, until the head-on view becomes a profile that reveals a flash of electric blue. As the Gerard Manley Hopkins line has it (borrowed for the title of Alex Preston’s book on birdwatching), kingfishers “catch fire.” Lyrical writing and self-deprecating honesty about the necessity of waiting (perhaps in the soaking rain) for moments of magic made this a lovely read. “Colour is to kingfishers what slipperiness is to eels. … Vanishing and theory-shattering are what kingfishers do best.”

In Otter, Crumley ranges a bit more widely, prioritizing outlying Scottish islands from Shetland to Skye. It’s on Mull that he has the best views, seeing four otters in one day, though “no encounter is less than unforgettable.” He watches them playing with objects and tries to talk back to them by repeating their “Haah?” sound. “Everything I gather from familiar landscapes is more precious as a beholder, as a nature writer, because my own constant presence in that landscape is also a part of the pattern, and I reclaim the ancient right of my own species to be part of nature myself.”

From time to time we see a kingfisher flying down the canal. Some of our neighbors have also seen an otter swimming across from the end of the gardens, but despite our dusk vigils we haven’t been so lucky as to see one yet. I’ve only seen a wild otter once, at Ham Wall Nature Reserve in Somerset. One day, maybe there will be one right here in my backyard. (Public library)

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil (2020)

[160 pages]

Nezhukumatathil, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi, published four poetry collections before she made a splash with this beautifully illustrated collection of brief musings on species and the self – this was shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize. Some of the 28 pieces spotlight an animal simply for how head-shakingly wondrous it is, like the dancing frog or the cassowary. More often, though, a creature or plant is a figurative vehicle for uncovering an aspect of her past. An example: “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun. Don’t get too dark … our mother would remind us as we ambled out into the relentless midwestern light.”

Nezhukumatathil, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi, published four poetry collections before she made a splash with this beautifully illustrated collection of brief musings on species and the self – this was shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize. Some of the 28 pieces spotlight an animal simply for how head-shakingly wondrous it is, like the dancing frog or the cassowary. More often, though, a creature or plant is a figurative vehicle for uncovering an aspect of her past. An example: “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun. Don’t get too dark … our mother would remind us as we ambled out into the relentless midwestern light.”

The author’s Indian/Filipina family moved frequently for her mother’s medical jobs, and sometimes they were the only brown people around. Loneliness, the search for belonging and a compulsion to blend in are thus recurrent themes. As an adult, traveling for poetry residencies and sabbaticals exposes her to new species like whale sharks. Childhood trips back to India allowed her to spend time among peacocks, her favorite animal. In the American melting pot, her elementary school drawing of a peacock was considered unacceptable, but when she featured a bald eagle and flag instead she won a prize.

These pinpricks of the BIPOC experience struck me more powerfully than the actual nature writing, which can be shallow and twee. Talking to birds, praising the axolotl’s “smile,” directly addressing the reader – it’s all very nice, but somewhat uninformed; while she does admit to sadness and worry about what we are losing, her sunny outlook seemed out of touch at times. On the one hand, it’s great that she wanted to structure her fragments of memoir around amazing animals; on the other, I suspect that it cheapens a species to only consider it as a metaphor for the self (a vampire squid or potoo = her desire to camouflage herself in high school; flamingos = herself and other fragile long-legged college students; a bird of paradise = the guests dancing the Macarena at her wedding reception).

My favorite pieces were one on the corpse flower and the bookend duo on fireflies – she hits just the right note of nostalgia and warning: “I know I will search for fireflies all the rest of my days, even though they dwindle a little bit more each year. I can’t help it. They blink on and off, a lime glow to the summer night air, as if to say, I am still here, you are still here.”

With thanks to Souvenir Press for the free copy for review.

Any nature books on your reading pile?

Nonfiction Week of #NovNov: Short Memoirs by Lucille Clifton, Alice Thomas Ellis and Deborah Levy

It’s nonfiction week of Novellas in November, which for me usually means short memoirs (today) and nature books (coming up on Wednesday). However, as my list of 10 nonfiction favorites from last year indicates, there’s no shortage of subjects covered in nonfiction works of under 200 pages; whether you’re interested in bereavement, food, hospitality, illness, mountaineering, nature, politics, poverty or social justice, you’ll find something that suits. This week is a great excuse to combine challenges with Nonfiction November, too.

We hope some of you will join in with our buddy read for the week, The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free to download here from Project Gutenberg if you don’t already have access). At a mere 85 pages, it’s a quick read. I’ve been enjoying learning about her family history and how meeting her teacher was the solution to her desperate need to communicate.

My first three short nonfiction reads of the month are all in my wheelhouse of women’s life writing, with each one taking on a slightly different fragmentary form.

Generations: A Memoir by Lucille Clifton (1976)

[87 pages]

After her father’s death, Clifton, an award-winning poet, felt compelled to delve into her African American family’s history. Echoing biblical genealogies, she recites her lineage in a rhythmic way and delivers family anecdotes that had passed into legend. First came Caroline, “Mammy Ca’line”: born in Africa in 1822 and brought to America as a child slave, she walked north from New Orleans to Virginia at age eight, became a midwife, and died free. Mammy Ca’line’s sayings lived on through Clifton’s father, her grandson: she “would tell us that we was Sayle people and we didn’t have to obey nobody. You a Sayle, she would say. You from Dahomey women.” Then came Caroline’s daughter, Lucy Sale, famously the first Black woman hanged in Virginia – for shooting her white lover. And so on until we get to Clifton herself, who grew up near Buffalo, New York and attended Howard University.

After her father’s death, Clifton, an award-winning poet, felt compelled to delve into her African American family’s history. Echoing biblical genealogies, she recites her lineage in a rhythmic way and delivers family anecdotes that had passed into legend. First came Caroline, “Mammy Ca’line”: born in Africa in 1822 and brought to America as a child slave, she walked north from New Orleans to Virginia at age eight, became a midwife, and died free. Mammy Ca’line’s sayings lived on through Clifton’s father, her grandson: she “would tell us that we was Sayle people and we didn’t have to obey nobody. You a Sayle, she would say. You from Dahomey women.” Then came Caroline’s daughter, Lucy Sale, famously the first Black woman hanged in Virginia – for shooting her white lover. And so on until we get to Clifton herself, who grew up near Buffalo, New York and attended Howard University.

The chapter epigraphs from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” call into question how much of an individual’s identity is determined by their family circumstances. While I enjoyed the sideways look at slavery and appreciated the poetic take on oral history, I thought more detail and less repetition would have produced greater intimacy.

Reissued by NYRB Classics tomorrow, November 9th, with a new introduction by Tracy K. Smith. My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review.

Home Life, Book Four by Alice Thomas Ellis (1989)

[169 pages]

For four years, Ellis wrote a weekly “Home Life” column for the Spectator. Her informal pieces remind me of Caitlin Moran’s 2000s writing for the Times – what today might form the kernel of a mums’ blog. In short, we have a harried mother of five trying to get writing done while maintaining a household – but given she has homes in London and Wales AND a housekeeper, and that her biggest problems include buying new carpet and being stuck in traffic, it’s hard to work up much sympathy. These days we’d say, Check your privilege.

For four years, Ellis wrote a weekly “Home Life” column for the Spectator. Her informal pieces remind me of Caitlin Moran’s 2000s writing for the Times – what today might form the kernel of a mums’ blog. In short, we have a harried mother of five trying to get writing done while maintaining a household – but given she has homes in London and Wales AND a housekeeper, and that her biggest problems include buying new carpet and being stuck in traffic, it’s hard to work up much sympathy. These days we’d say, Check your privilege.

The sardonic complaining rubbed me the wrong way, especially when the subject was not finding anything she wanted to read even though she’d just shipped four boxes of extraneous books off to her country house, or using noxious sprays to get rid of one harmless fly, or a buildup of rubbish bags because they’d been “tidying.” These essays feel of their time for the glib attitude and complacent consumerism. It’s rather a shame they served as my introduction to Ellis, but I think I’d still give her fiction a try. (Secondhand purchase, Barter Books)

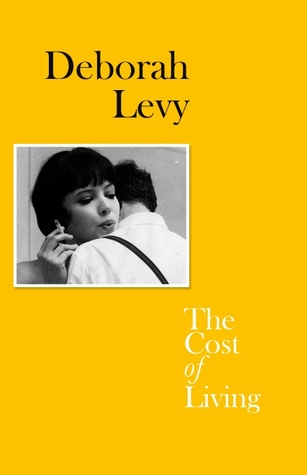

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy (2018)

[187 pages]

In the space of a year, Levy separated from her husband and her mother fell ill with the cancer that would kill her. Living with her daughters in a less-than-desirable London flat, she longed for a room of her own. Her octogenarian neighbor, Celia, proffered her garden shed as a writing studio, and that plus an electric bike conferred the intellectual and physical freedom she needed to reinvent her life. That is the bare bones of this sparse volume, the middle one in an autobiographical trilogy, onto which Levy grafts the tissue of experience: conversations and memories; travels and quotations that have stuck with her.

In the space of a year, Levy separated from her husband and her mother fell ill with the cancer that would kill her. Living with her daughters in a less-than-desirable London flat, she longed for a room of her own. Her octogenarian neighbor, Celia, proffered her garden shed as a writing studio, and that plus an electric bike conferred the intellectual and physical freedom she needed to reinvent her life. That is the bare bones of this sparse volume, the middle one in an autobiographical trilogy, onto which Levy grafts the tissue of experience: conversations and memories; travels and quotations that have stuck with her.

It’s hard to convey just what makes this brilliant. The scenes are everyday – set at her apartment complex, during her teaching work or on a train; the dialogue might be overheard. Yet each moment feels perfectly chosen to reveal her self, or the emotional truth of a situation, or the latent sexism of modern life. “All writing is about looking and listening and paying attention to the world,” she writes, and it’s that quality of attention that sets this apart. I’ve had mixed success with Levy’s fiction (though I loved Hot Milk), but this was flawless from first line to last. I can only hope the rest of the memoir lives up to it. (New purchase)

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Any short nonfiction on your reading pile?

Open Water & Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year (#NovNov)

Open Water is our first buddy read, for Contemporary week of Novellas in November (#NovNov). Look out for the giveaway running on Cathy’s blog today!

I read this one back in April–May and didn’t get a chance to revisit it, but I’ll chime in with my brief thoughts recorded at the time. I then take a look back at 14 other novellas I’ve read this year; many of them I originally reviewed here. I also have several more contemporary novellas on the go to round up before the end of the month.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (2021)

[145 pages]

I always enjoy the use of second person narration, and it works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles.

I always enjoy the use of second person narration, and it works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles.

Ultimately, I wasn’t convinced that fiction was the right vehicle for this story, especially with all the references to other authors, from Hanif Abdurraqib to Zadie Smith (NW, in particular); I think a memoir with cultural criticism was what the author really intended. I’ll keep an eye out for Nelson, though – I wouldn’t be surprised if this makes it onto the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist in January. I feel like with his next book he might truly find his voice.

Readalikes:

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (also appears below)

- Poor by Caleb Femi (poetry with photographs)

- Normal People by Sally Rooney

Other reviews:

Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year:

(Post-1980; under 200 pages)

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

Assembly by Natasha Brown

Indelicacy by Amina Cain

A Lie Someone Told You About Yourself by Peter Ho Davies

Blue Dog by Louis de Bernières

The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans

Anarchipelago by Jay Griffiths

Tinkers by Paul Harding

An Island by Karen Jennings

Ness by Robert Macfarlane

Black Dogs by Ian McEwan

Broke City by Wendy McGrath

A Feather on the Breath of God by Sigrid Nunez

In the Winter Dark by Tim Winton

Currently reading:

- Inside the Bone Box by Anthony Ferner

- My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson

- The Cemetery in Barnes by Gabriel Josipovici

What novellas do you have underway this month? Have you read any of my selections?

Novellas in November (#NovNov) Begins! Leave Your Links Here

I always look forward to November’s reading. Since 2016 I’ve been prioritizing novellas in this month, but this is only the second year that Cathy of 746 Books and I have co-hosted Novellas in November as a proper reading challenge.

We have four weekly prompts and “buddy reads” as below. We hope you’ll join in reading one or more of these with us. The host for the week will aim to publish her review on the Thursday, but feel free to post yours at any time in the month. (A reminder that we suggest 150–200 pages as the upper limit for a novella, and post-1980 for the contemporary week.)

1–7 November: Contemporary fiction (Cathy)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson – including a giveaway of a signed copy!

8–14 November: Short nonfiction (Rebecca)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free to download here from Project Gutenberg. Note: only the first 85 pages constitute her memoir; the rest is letters and supplementary material.)

15–21 November: Literature in translation (Cathy)

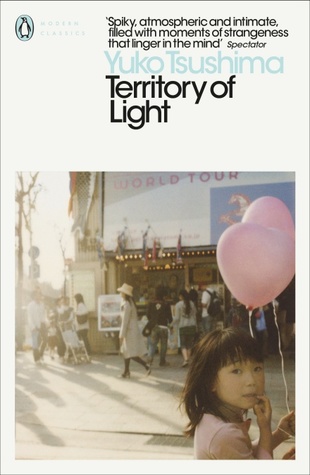

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima

22–28 November: Short classics (Rebecca)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (free to download here from Project Gutenberg)

Leave links to any of your novellas coverage in the comments below or tag us on Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and/or Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books) and we’ll add them to a master list.

Enjoy your reading!

Ongoing list of Novellas in November 2021 posts:

Five novellas: de Kat, Lynch, Mingarelli, Sjón, Terrin (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

The Disinvent Movement by Susanna Gendall (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Four novellas with screen adaptations (a list by Diana at Ripple Effects)

Contemporary novellas from the archives (a list by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Moral Hazard by Kate Jennings (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

A Child in the Theatre by Rachel Ferguson (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Death of the Author by Gilbert Adair (reviewed by Karen at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings)

Come Closer by Sara Gran (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Amsterdam by Ian McEwan (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Five novellas: Burley, Capote, Hill, Steinbeck, Welsh (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Often I Am Happy by Jens Christian Grøndahl (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Vertigo by Amanda Lohrey (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Open Water & Other Contemporary Novellas Read This Year

An Island by Karen Jennings (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

At Night All Blood Is Black by David Diop (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

Stone in a Landslide by Maria Barbal (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

I’m Ready Now by Nigel Featherstone (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Lonely by Paul Gallico (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Love Child by Edith Olivier (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Murder Included by Joanna Cannan (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald: From Novella to Movie (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

The River by Rumer Godden (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Rector and The Doctor’s Family by Mrs Oliphant (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Less than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis (reviewed by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

Foe by J.M. Coetzee (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Short Non-fiction from the archives (a list by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Nonfiction November: Book Pairing – Novellas and Nonfiction (a list by Cathy at 746 Books)

Casanova’s Homecoming by Arthur Schnitzler (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Which Way? by Theodora Benson (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Short Memoirs by Lucille Clifton, Alice Thomas Ellis and Deborah Levy

Aimez-vous Brahms? by Françoise Sagan (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Birds of the Innocent Wood by Deirdre Madden (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Baron Bagge by Alexander Lernet-Holenia (reviewed by Grant at 1streading)

The Poor Man by Stella Benson (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Short Nature Books by John Burnside, Jim Crumley and Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Hiroshima by John Hersey (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Short nonfiction by Athill, Herriot and Mantel (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Story of Stanley Brent by Elizabeth Berridge (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Parakeeting of London by Nick Hunt and Tim Mitchell (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

Taking a Look Back at Novellas Read in 2021 (a list by JDC at Gallimaufry Book Studio)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (a review by Mairead at Swirl and Thread)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Faces by Tove Ditlevsen (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

Coda by Thea Astley (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

I’d Rather Be Reading by Anne Bogel (reviewed by Karen at The Simply Blog)

Notes from an Island by Tove Jansson (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Clare at Years of Reading Selfishly)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Looking Glass by Carla Sarett (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Daisy Miller by Henry James (reviewed by Diana at Thoughts on Papyrus)

Heritage by Vita Sackville-West (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

One Billion Years to the End of the World by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes (reviewed by Tracy at Bitter Tea and Mystery)

We Kill Stella by Marlen Haushofer and Come Closer by Sara Gran (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Tea and Sympathetic Magic by Tansy Rayner Roberts (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Passing by Nella Larsen, from Novella to Screen (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

The Employees by Olga Ravn and A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Maigret in Court by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

No. 91/92: A Diary of a Year on the Bus by Lauren Elkin (reviewed by Rebecca at Reading Indie)

Six Scottish Novellas: Gray, Mackay Brown, Mitchison, Muir, Owens, Smith (reviewed by Grant at 1streading)

Cain by José Saramago (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Pear Field by Nana Ekvtimishvili (Booktube review by Jennifer at Insert Literary Pun Here)

Tinkers by Paul Harding (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Concrete by Thomas Bernhard (reviewed by Emma at Book Around the Corner)

Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg by Emily Rapp Black (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

Utility Furniture by Jon Mills (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Symposium by Muriel Spark (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

Griffith Review #66, The Light Ascending, annual Novella Project edition (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

SixforSunday: Novellas Read in 2021 before November (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

The Silent Traveller in Oxford by Chiang Yee (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The War of the Poor by Éric Vuillard (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Spoke by Friedrich Glauser (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Dinner by César Aira (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Scrolls from the Dead Sea by Edmund Wilson (reviewed by Reese at Typings)

The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

The White Riband by F. Tennyson Jesse (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Translated fiction novellas from the archives, including Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

I Don’t Want to Go to the Taj Mahal by Charlie Hill (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Miss Peabody’s Inheritance by Elizabeth Jolley (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

Hotel Iris by Yoko Ogawa (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Crusade by Amos Oz (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

Barbarian Spring by Jonas Lüscher (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Eric at Lonesome Reader)

Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Particularly Cats by Doris Lessing (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

The Murder Farm by Andrea Maria Schenkel and The Peacock by Isabel Bogdan (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Assembly by Natasha Brown (reviewed at Radhika’s Reading Retreat)

Ludmilla by Paul Gallico (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

The Woman from Uruguay by Pedro Mairal (reviewed by Susan at A life in books)

An interview with Stella Sabin of Peirene Press (by Cathy at 746 Books)

Behind the Mask by Kate Walter

The Pigeon and The Appointment

In the Company of Men and Winter Flowers

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns

The Deal of a Lifetime by Fredrik Backman (reviewed by Karen at The Simply Blog)

Carte Blanche by Carlo Lucarelli (reviewed by Tracy at Bitter Tea and Mystery)

Inspector Chopra & the Million Dollar Motor Car by Vaseem Khan (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

Bunner Sisters by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

Father Malachy’s Miracle by Bruce Marshall (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Ignorance by Milan Kundera (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Rider on the Rain by Sébastien Japrisot and The Saint-Fiacre Affair by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Hotel Splendid by Marie Redonnet and Fear by Stefan Zweig (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Some classics from my archives (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

The Cardinals by Bessie Head (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

These Lifeless Things by Premee Mohamed, A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers, The Deep by Rivers Solomon (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

Four novellas, four countries, four decades (reviewed by Emma at Book Around the Corner)

Daphnis and Chloe by Longus (reviewed by Reese at Typings)

The Invisible Host by Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

In Youth Is Pleasure by Denton Welch (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

The Newspaper of Claremont Street by Elizabeth Jolley (reviewed by Nancy Elin)

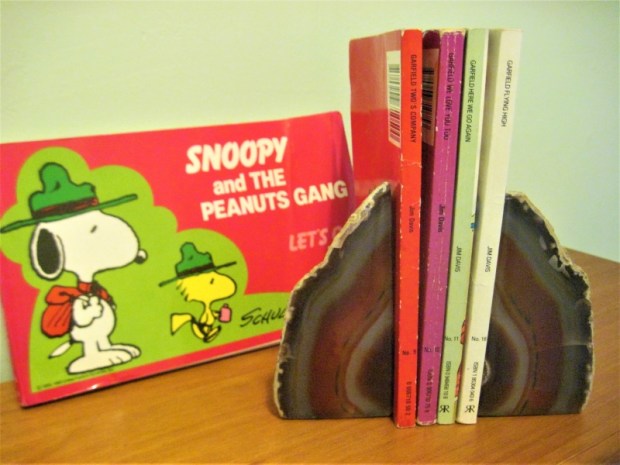

Six Short Cat Books: Muriel Barbery, Garfield and More

Catholics by Brian Moore (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

I’d Rather Be Reading by Anne Bogel (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

A River in Darkness by Masaji Ishikawa (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

The Witch of Clatteringshaws by Joan Aiken (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

The Turn of the Screw by Henry James (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Three to See the King by Magnus Mills (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Touring the Land of the Dead by Maki Kashimada and Stranger Faces by Namwali Serpell (reviewed by Dr Laura Tisdall)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Love by Angela Carter (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Novellas in November 2021 Wrap Up (by Carol at Reading Ladies)

A Guide to Modernism in Metroland by Joshua Abbott and Black London by Avril Nanton and Jody Burton (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Karen at The Simply Blog)

Signs Preceding the End of the World by Yuri Herrera (reviewed by Karen at BookerTalk)

Madonna in a Fur Coat by Sabahattin Ali (reviewed by Imogen at Reading and Watching the World)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Davida at TCL Book Reviews)

Clara’s Daughter by Meike Ziervogel (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

Breakfast at Tiffany’s: from Novella to Screen (reviewed by Diana at Ripple Effects)

Child of All Nations by Irmgard Keun (reviewed by Marina Sofia at Finding Time to Write)

Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

Three Contemporary Novellas: Moss, Brown and Gaitskill (reviewed by Cathy at 746 Books)

Seven Final Novellas: Crumley, Morris, Rapp Black; Hunter, Johnson, Josipovici, Otsuka

In Pious Memory by Margery Sharp (reviewed by HeavenAli)

Murder in the Dark by Margaret Atwood, The Story of Stanley Brent by Elizabeth Berridge, Under the Tripoli Sky by Kamal Ben Hameda (reviewed by HeavenAli)

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood (reviewed by She Reads Novels)

Caravan Story by Wayne Macauley (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Farmer Giles of Ham by J.R.R. Tolkien (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

I Am God, a Novel by Giacomo Sartori (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die by Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay (reviewed by Erdeaka at The Bookly Purple)

Second-Class Citizen by Buchi Emecheta (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Invention of Morel by Adolfo Bioy Casares (reviewed by Emma at Words and Peace)

The Fell by Sarah Moss (reviewed by Callum McLaughlin)

Women & Power by Mary Beard and Come Closer by Sara Gran (reviewed by Callum McLaughlin)

The Tobacconist by Robert Seethaler and I Was Jack Mortimer by Alexander Lernet-Holenia (reviewed by Madame Bibi Lophile)

Things I Don’t Want to Know and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy (reviewed by Madame Bibi Lophile)

Touch the Water, Touch the Wind by Amos Oz (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

The Woman in the Blue Cloak by Deon Meyer (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

The White Woman by Liam Davison (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

Boys Don’t Cry by Fiona Scarlett (reviewed by Kim at Reading Matters)

Fludd by Hilary Mantel (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Pietr the Latvian by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

In Translation by Annamarie Jagose (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

The Red Chesterfield by Wayne Arthurson, The Book of Eve by Constance Beresford-Howe, Tower by Frances Boyle, Winter Wren by Theresa Kishkan, and The Santa Rosa Trilogy by Wendy McGrath (reviewed by Naomi at Consumed by Ink)

An essay on Kate Jennings’ Snake (reviewed by Whispering Gums)

Life in Translation by Anthony Ferner and Friend Indeed by Katharine d’Souza (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Every Day Is Gertie Day by Helen Meany (reviewed by Whispering Gums)

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au (reviewed by Brona’s Books at This Reading Life)

A Dream Life by Claire Messud (reviewed by Brona’s Books at This Reading Life)

Why Do I Like Novellas? Barnes, Brown, Jones, Ravn (reviewed by Stargazer)

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Callum McLaughlin)

Foster by Claire Keegan (reviewed by Smithereens)

The Light in the Piazza by Elizabeth Spencer (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

King City by Stephen Pennell (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

Missus by Ruth Park (reviewed by Lisa at ANZ LitLovers)

Inseparable by Simone de Beauvoir (reviewed by Anokatony at Tony’s Book World)

I Heard the Owl Call My Name by Margaret Craven (reviewed by Robin at A Fondness for Reading)

Maigret Defends Himself by Georges Simenon (reviewed by Chris at Calmgrove)

My Week with Marilyn by Colin Clark (reviewed by Kate at Books Are My Favourite and Best)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Margaret at BooksPlease)

Miguel Street by V.S. Naipaul (reviewed by Liz at Adventures in reading, running and working from home)

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey, Naturally Supernatural by Wendy Mann, The Hothouse by the East River by Muriel Spark, Trouble with Lichen by John Wyndham (reviewed by Simon at Stuck in a Book)

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton (reviewed by Laura at Reading in Bed)

Assembly by Natasha Brown, Treacle Walker by Alan Garner, All the Devils Are Here by David Seabrook, Space Exploration by Dhara Patel (reviewed by Annabel at Annabookbel)

Bellow, Powell, Wolkers, Bomans, al-Saadawi, de Jong, Buck, Simenon, Boschwitz (reviewed by Sarah at Market Garden Reader)

More Ideas of Novellas to Read for #NovNov

Still in need of ideas for what to read in November? Here are our novella-friendly lists of authors and publishers that fit the bill!

Authors who tend(ed) to write short books:

- James Baldwin

- J.L. Carr

- Barbara Comyns

- Alice Thomas Ellis

- Penelope Fitzgerald

- Paul Gallico

- Kaye Gibbons

- Susan Hill

- Denis Johnson – Train Dreams was one of our most-reviewed books last year

- Gabriel Josipovici

- Claire Keegan

- Shena Mackay

- Ian McEwan

- Sarah Moss’s three latest

- Jean Rhys

- Georges Simenon

- Muriel Spark

- John Steinbeck

- Nathanael West

- Jacqueline Woodson

In nonfiction – nature books:

- Jim Crumley

- John Lewis-Stempel

In nonfiction – animal/pet books:

- Derek Tangye

- Doreen Tovey

UK publishers that specialize in novellas:

Fitzcarraldo Editions (especially their early releases)

Penguin’s Little Black Classics series

Worldwide publishers that specialize in novellas:

Fish Gotta Swim Editions (Canada)

Melville House – “The Art of the Novella” series (USA)

Nouvella (USA) – Take a look at the last couple of rows on their merchandise page!

Quattro Books (Canada)

UK publishers that specialize in novellas in translation:

Charco Press – contemporary Latin American literature

Fitzcarraldo Editions

Holland Park Press

Les Fugitives – translations from the French

Lolli Editions (thanks to Annabel for this one)

Peirene Press – Cathy will be hosting an interview with them during translation week!

Pushkin Press

UK sources of short nonfiction:

Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series

Fitzcarraldo Editions – some of their longform essays are under 200 pages

Penguin’s Great Ideas series

Little Toller Books – mostly nature and travel monographs

The School of Life – most of the ones in this particular series are under 200 pages

Oxford University Press’s Very Short Introductions series

Wellcome Collection Books – a number of their recent releases are under 200 pages

You could also check out some of last year’s Novellas in November content: 89 posts from 30 bloggers, including single reviews, multi-reviews and favourites lists.

Still stumped? Try these articles:

(Note: not all of the suggestions stick to our definition of a novella.)

- Brona’s list of Australian novellas

- “20 of the Best Short Classic Books” (Book Riot)

- Novellas: A Life List (Fish Gotta Swim)

- “10 Best Books Shorter than 150 Pages” (Publishers Weekly)

- “50 Must-Read Short Books in Translation” (Book Riot)

- “50 Must-Read Short Books under 250 Pages” (Book Riot)

- “50 Short Nonfiction Books You Can Read in a Day (or Two)” (Book Riot)

And, if you’re looking for a bit of context, the other year Laura F. put together a history of the Novellas in November challenge.

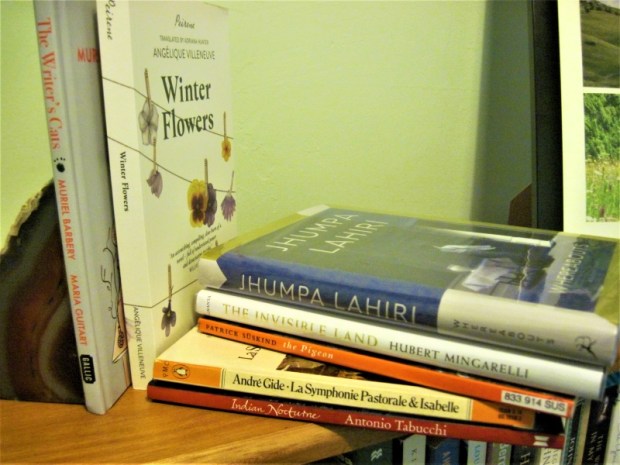

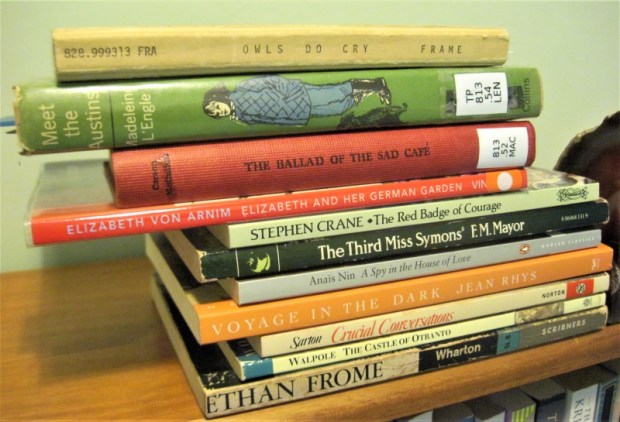

Planning My Reading Stacks for Novellas in November 2021

Not much more than a week until Novellas in November (#NovNov) begins! I gathered up all of my potential reads for a photo shoot. Review copies are stood upright and library loans are toggled in a separate pile on top; all the rest are from my shelves.

Week One: Contemporary Fiction

Week Two: Short Nonfiction

Week Three: Novellas in Translation

A rather pathetic little pile there, but I also have a copy of that week’s buddy read, Territory of Light by Yuko Tsushima, on the way. (The Pigeon by Patrick Süskind would be my token contribution to German Literature Month.)

Week Four: Short Classics

Last but not least, some comics collections that don’t seem to fit in one of the other categories. Of course, some books fit into two or more categories, and contemporary vs. classic feels like a fluid division – I haven’t checked rigorously for our suggested 1980 cut-off date, so some older stuff might have made it into different piles.

Also available on my Kindle: The Therapist by Nial Giacomelli, Record of a Night too Brief by Hiromi Kawakami, Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Reve, and Milton in Purgatory by Edward Vass. As an additional review copy on my Nook, I have Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg by Emily Rapp Black, which is 140-some pages.

Also available on my Kindle: The Therapist by Nial Giacomelli, Record of a Night too Brief by Hiromi Kawakami, Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Reve, and Milton in Purgatory by Edward Vass. As an additional review copy on my Nook, I have Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg by Emily Rapp Black, which is 140-some pages.

Plus … I recently placed an order for some new and secondhand books with my birthday money (and then some), and it should arrive before the end of the month. On the way and of novella length are Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns, Bear by Marian Engel, The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy, and In the Company of Men by Véronique Tadjo.

Plus … I recently placed an order for some new and secondhand books with my birthday money (and then some), and it should arrive before the end of the month. On the way and of novella length are Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns, Bear by Marian Engel, The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy, and In the Company of Men by Véronique Tadjo.

I also recently requested review copies of Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan (128 pages; coming out from Faber today) and The Fell by Sarah Moss (160 pages; coming out from Picador on November 11th), so hope to have those in hand soon.

Remember that this year we have chosen a buddy read for each week. I’m again looking after short nonfiction in the second week of the month and short classics in the final week. We plan to post our reviews on the Thursday or Friday of the week in question. Feel free to publish yours at any time in the month and we’ll round up the links on our review posts.

Superman Simon is thinking of reading a novella a day in November! Taken together, I’d have enough novellas here for TWO per day. But my record thus far (in 2018) is 26; since then, I’ve managed 16 per year.

I have no specific number in mind this time. Considering I also plan to read one or two books for Margaret Atwood Reading Month (and perhaps one for AusReading Month) and have a blog tour date, as well as other review books to catch up on and in-demand library books to keep on top of, I can’t devote my full attention to novellas.

If I can read all the review copies, mop up the 4–5 set-aside titles on the pile (the ones with bookmarks in), maybe manage two rereads (the Wharton plus Conundrum), make a dent in my owned copies, and get to one or more from the library, I’ll be happy.

Karen, Kate and Margaret have already come up with their lists of possible titles. Cathy’s has gone up today, too.

Dark and carefully chiselled, the chapters are like tiny diamonds that you have to hold up to the light to see the glitter. Newly separated from her husband, the unnamed narrator, who works at a music library, entrusts us with vignettes from her first year of single parenthood. She is honest about her bad behaviour – the nights she got falling down drunk and invited men back to the apartment; the mornings she missed the daycare dropoff deadline and let her two-year-old fend for herself while she stayed in bed. Alongside the custody battle with her ex are smaller feuds, like with her neighbour, who’s had enough of the little girl dropping things onto his roof from the windows above and gets the landlord to do something about it.

Dark and carefully chiselled, the chapters are like tiny diamonds that you have to hold up to the light to see the glitter. Newly separated from her husband, the unnamed narrator, who works at a music library, entrusts us with vignettes from her first year of single parenthood. She is honest about her bad behaviour – the nights she got falling down drunk and invited men back to the apartment; the mornings she missed the daycare dropoff deadline and let her two-year-old fend for herself while she stayed in bed. Alongside the custody battle with her ex are smaller feuds, like with her neighbour, who’s had enough of the little girl dropping things onto his roof from the windows above and gets the landlord to do something about it.