Tag Archives: R.O. Kwon

My Life in Book Titles from 2024

As usual for January, I’m in the middle of lots of books but hardly finishing anything, so consider this a placeholder until my Love Your Library and January releases posts later in the month. It’s a fun meme that goes around every year; I first spotted it on Annabel’s blog and Susan also took part. I’ve never had a go before but when I looked at the prompts I realized some books I read in 2024 have titles that work awfully well. Links are to my reviews.

In high school I was [one of the] Remarkably Bright Creatures (Shelby Van Pelt)

In high school I was [one of the] Remarkably Bright Creatures (Shelby Van Pelt)

- People might be surprised by All the Beauty in the World (Patrick Bringley)

- I will never be A Spy in the House of Love (Anaïs Nin)

My fantasy job is To Be a Cat (Matt Haig)

My fantasy job is To Be a Cat (Matt Haig)

- At the end of a long day, I need [a] Cocktail (Lisa Alward)

- I hate being [an] Exhibit (R.O. Kwon)

- Wish I had Various Miracles (Carol Shields)

- My family reunions are The Grief Cure (Cory Delistraty)

At a party you’d find me with Orphans of the Carnival (Carol Birch)

At a party you’d find me with Orphans of the Carnival (Carol Birch)

- I’ve never been to Jungle House (Julianne Pachico)

A happy day includes The Old Haunts (Allan Radcliffe)

A happy day includes The Old Haunts (Allan Radcliffe)

- Motto I live by: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself (Glynnis MacNicol)

On my bucket list is A Bookshop of One’s Own (Jane Cholmeley)

On my bucket list is A Bookshop of One’s Own (Jane Cholmeley)

- In my next life, I want to have A House Full of Daughters (Juliet Nicolson)

Carol Shields Prize Longlist Reads: Cocktail & Land of Milk and Honey

Two final reviews in advance of tomorrow’s shortlist announcement: a sophisticated, nostalgic short story collection and an intense future-set novel full of the pleasures of the flesh. Both make it onto my wish list at the end of this post.

Cocktail by Lisa Alward

The 12 stories of this debut collection brought to mind Tessa Hadley and Alice Munro for their look back at chic or sordid 1960s–1980s scenes and dysfunctional families or faltering marriages. They’re roughly half and half first-person and third-person (five versus seven). The title story opens the book with a fantastic line: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.” Later, the narrator elaborates:

Her meaning is that if people drank more, they’d loosen up. Parties would be more fun, like they used to be. And I laugh along. Yes, I say, letting her top up my glass of Chardonnay. That’s it, not enough booze. But I’m thinking about Tom Collins.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

Not the drink, but an alias a party guest used when he stumbled into her bedroom looking for a toilet. She was about eleven at this point and she and her brother vaguely resented being shut away from their parents’ parties. While for readers this is an uncomfortable moment as we wonder if she’s about to be molested, in memory it’s taken on a rosy glow for her – a taste of adult composure and freedom that she has sought with every partner and every glass of booze since. This was a pretty much perfect story, with a knock-out ending to boot.

Dependence on alcohol recurs, and “Hawthorne Yellow,” is also about a not-quite affair, between a restless stay-at-home mother and the decorator who discovers antique sketches in the old servants’ quarters of her home. “Orlando, 1974” again contrasts childhood nostalgia with seedy reality: Disney World should have been an idyll, but the narrator mostly remembers a lot of vomiting. “Old Growth” and “Bear Country” have Ray renegotiating his relationship with his son after divorcing Gwyneth. “Hyacinth Girl,” too, is about complicated stepfamilies, while “Wise Men Say” looks back at cross-class romance. The protagonist of “Maeve” feels she can’t match the title character’s perfect parenting skills; the first-person plural in “Pomegranate” portrays a group of wild convent schoolgirls.

“Little Girl Lost” was the most Hadley-meets-Munro, with an alcoholic painter’s daughter seen first as a half-feral child and later as a hippie young woman. “How the Smoke Gets in Your Eyes” was the least essential with its elderly narrator piecing things together in the aftermath of a burglary. Along with the title story, the standout for me was “Bundle of Joy,” about a persnickety grandmother going to her daughter’s place to spend time with her new grandson. She disapproves of just about every decision Erin has made (leaving the dogs’ frozen turds in the backyard all winter, for instance), but her interference threatens to have lasting consequences. Not a dud in the dozen, and a very strong voice I’ll expect to read much more from. (Read via Edelweiss; published by Biblioasis) ![]()

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang

We all die. We have only the choice, if we are privileged, of whether death comes with a whimper or a bang; of what worlds we taste before we go.

A real step up from How Much of These Hills Is Gold, which I read for book club last year – while it was interesting to see the queer, BIPOC spin Zhang put on the traditional Western, I found her Booker-longlisted debut bleak and strange in such a detached way that it was hard to care about. By contrast, I was fully involved in her sensuous and speculative second novel.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

A 29-year-old Chinese American chef is exiled when the USA closes its borders while she’s working in London. On a smog-covered planet where 98% of crops have failed, scarcity reigns – but there is a world apart, a mountaintop settlement at the Italian border where money can buy any ingredient desired and threatened foods are cultivated in a laboratory setting. While peasants survive on mung bean flour, wealthy backers indulge in classic French cuisine. The narrator’s job is to produce lavish, evocative multi-course meals to bring investors on board. Foie gras, oysters, fine wines; heirloom vegetables; fruits not seen for years. But also endangered creatures and mystery meat wrested back from extinction. Her employer’s 21-year-old daughter, Aida, oversees the lab where these rarities are kept alive.

Ironically, surrounded with such delicacies, the chef loses her appetite for all but cigarettes – yet another hunger takes over. Her relationship with Aida is a passionate secret made all the more peculiar by the fact that the chef’s other role is to impersonate Aida’s dead mother, Eun-Young. It’s clear this precarious setup can’t last; ambition and technology keep moving on. The novel presents such a striking picture of desire at the end of the world. Each sentence is honed to flawlessness, with whole paragraphs of fulsome descriptions of meals. Zhang’s prose reminded me of Stephanie Danler’s and R.O. Kwon’s – no surprise, then, that they’re on the Acknowledgments list, as are a cornucopia of foods and other literary influences.

I’m not usually one for a dystopian novel, but the emotional territory keeps this one grounded even as the plot grows more sinister. My only complaint is that I would have left off the final chapter as I don’t think tracing the protagonist through four more decades of life adds much. I would rather have left this world in limbo than thought of the episode as a blip in a facile regeneration process – that’s the most unrealistic element of all. But this has still been my favourite read from the longlist so far. And there’s even a faithful pet cat, a “recalcitrant beast” that keeps coming back to the chef despite benign neglect. (Public library) ![]()

My ideal shortlist, based on what I’ve read and still want to read, would be:

Cocktail by Lisa Alward

Dances by Nicole Cuffey

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang

I wouldn’t be averse to seeing The Future or Chrysalis on there either. (Just not Loot, please!)

See Laura’s post for a recap of her reviews and her wish list. Marcie has also been reading from the longlist; see her first write-up here.

Book Serendipity, January to February 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- I finished two poetry collections by a man with the surname Barnett within four days in January: Murmur by Cameron Barnett and Birds Knit My Ribs Together by Phil Barnett.

- I came across the person or place name Courtland in The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty, then Cortland in a story from The Orange Fish by Carol Shields, then Cotland (but where? I couldn’t locate it again! Was it in Elizabeth Is Missing by Emma Healey?).

- The Manet painting Olympia is mentioned in Christmas Holiday by W. Somerset Maugham and The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl (both of which are set in Paris).

- There’s an “Interlude” section in Babel by R.F. Kuang and The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez.

- The Morris (Minor) car is mentioned in Elizabeth Is Missing by Emma Healey and Various Miracles by Carol Shields.

- The “flour/flower” homophone is mentioned in Babel by R.F. Kuang and Various Miracles by Carol Shields.

- A chimney swift flies into the house in Cat and Bird by Kyoko Mori and The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty.

- A character named Cornelius in The Fruit Cure by Jacqueline Alnes and Wellness by Nathan Hill.

- Reading two year challenge books at the same time, A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Local by Alastair Humphreys, both of which are illustrated with frequent black-and-white photos by and of the author.

- A woman uses a bell to summon children in one story of Universally Adored and Other One Dollar Stories by Elizabeth Bruce and The Optimist’s Daughter by Eudora Welty.

- Apple turnovers get a mention in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Wellness by Nathan Hill.

- A description of rolling out pie crust in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Cat and Bird by Kyoko Mori.

- The idea of a house giving off good or bad vibrations in Wellness by Nathan Hill and a story from Various Miracles by Carol Shields.

- Emergency C-sections described or at least mentioned in Brother Do You Love Me by Manni Coe, The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan, Wellness by Nathan Hill, and lots more.

- Frustration with a toddler’s fussy eating habits, talk of “gentle parenting” methods, and mention of sea squirts in Wellness by Nathan Hill and Matrescence by Lucy Jones.

- The nickname “Poet” in The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and My Friends by Hisham Matar.

- A comment about seeing chicken bones on the streets of London in The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and Went to London, Took the Dog by Nina Stibbe.

- Swans in poetry in The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and Egg/Shell by Victoria Kennefick.

- A mention or image of Captcha technology in Egg/Shell by Victoria Kennefick and Went to London, Took the Dog by Nina Stibbe.

- An animal automaton in Loot by Tania James and Egg/Shell by Victoria Kennefick.

- A mention of Donna Tartt in The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley, Looking in the Distance by Richard Holloway, and Matrescence by Lucy Jones.

- Cathy Rentzenbrink appears in The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and Went to London, Took the Dog by Nina Stibbe.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

- An account of a man being forced to marry the sister of his beloved in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans, Wellness by Nathan Hill, and The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht.

- Saying that one doesn’t want to remember the loved one as ill (but really, not wanting to face death) so not saying goodbye (in Cat and Bird by Kyoko Mori) or having a closed coffin (Wellness by Nathan Hill).

- An unhappy, religious mother who becomes a hoarder in Wellness by Nathan Hill and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy.

- Characters called Lidija and Jin in Exhibit by R. O. Kwon and Lydia and Jing in the first story of This Is Salvaged by Vauhini Vara.

- Distress at developing breasts in Cactus Country by Zoë Bossiere and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy.

- I came across mentions of American sportscaster Howard Cosell in Heartburn by Nora Ephron and Stations of the Heart by Richard Lischer (two heart books I was planning on reviewing together) on the same evening. So random!

- Girls kissing and flirting with each other (but it’s clear one partner is serious about it whereas the other is only playing or considers it practice for being with boys) in Cactus Country by Zoë Bossiere and Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell.

- A conversion to Catholicism in Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown and Stations of the Heart by Richard Lischer.

- A zookeeper is attacked by a tiger when s/he goes into the enclosure (maybe not the greatest idea!!) in Tiger by Polly Clark and The Tiger’s Wife by Téa Obreht.

- The nickname Frodo appears in Tiger by Polly Clark and Brother Do You Love Me by Manni Coe.

- Opening scene of a parent in a coma, California setting, and striking pink and yellow cover to Death Valley by Melissa Broder and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy.

- An Englishman goes to Nigeria in Howards End by E.M. Forster and Immanuel by Matthew McNaught.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

- A mother continues washing her daughter’s hair until she is a teenager old enough to leave home in Mrs. March by Virginia Feito and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy.

- Section 28 (a British law prohibiting the “promotion of homosexuality” in schools) is mentioned in A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me by Kate Clanchy, and Brother Do You Love Me by Manni Coe.

- Characters named Gord (in one story from Various Miracles by Carol Shields, and in Fight Night by Miriam Toews), Gordy (in The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie), and Gordo (in Blood Red by Gabriela Ponce).

- Montessori and Waldorf schools are mentioned in Cactus Country by Zoë Bossiere and When Fragments Make a Whole by Lory Widmer Hess.

- A trailer burns down in The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and Cactus Country by Zoë Bossiere.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

My Most Anticipated Releases of 2024

I feel a sense of freedom and anticipation about the reading opportunities stretching out ahead of me and want to preserve that, so apart from participating in my usual challenges and trying to read more from my own shelves, I have no specific reading goals for the year. (My ever-growing set-aside shelf does make me feel guilty, though.)

Knowing myself, close to half of my reading will be current-year releases. I’ve already read 10 releases from 2024 (8 are written up here), and I’m also looking forward to new work from Julia Armfield, Tracy Chevalier, Matt Gaw, Garth Risk Hallberg, Sheila Heti, Ann Hood, Rachel Khong, Sarah Manguso, Tommy Orange, Francesca Segal, Joe Shute and J. Courtney Sullivan. If there’s a recurring theme here, it’s sophomore novels from authors whose debuts I loved. Only a few nonfiction releases are musts for me.

I’ve chosen the dozen below as my most anticipated titles that I know about so far. They are arranged in UK release date order, within sections by genre. (U.S. details given too/instead if USA-only.) Quotes are excerpts from the publisher blurbs, e.g., from Goodreads. I’ve noted if I have sourced a review copy already.

Fiction

Wellness by Nathan Hill [Jan. 25, Picador; has been out since September from Knopf] Hill’s debut novel, The Nix, was fantastic. I’ve developed an allergy to doorstoppers over the past year, but am determined to read this anyway. “Moving from the gritty 90s Chicago art scene to a suburbia of detox diets and home renovation hysteria, Wellness mines the absurdities of modern technology and modern love to reveal profound, startling truths about intimacy and connection.” Has been likened to Egan, Franzen and Strout. (Print proof copy)

Wellness by Nathan Hill [Jan. 25, Picador; has been out since September from Knopf] Hill’s debut novel, The Nix, was fantastic. I’ve developed an allergy to doorstoppers over the past year, but am determined to read this anyway. “Moving from the gritty 90s Chicago art scene to a suburbia of detox diets and home renovation hysteria, Wellness mines the absurdities of modern technology and modern love to reveal profound, startling truths about intimacy and connection.” Has been likened to Egan, Franzen and Strout. (Print proof copy)

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez [Jan. 25, Virago; has been out since November from Riverhead] I’ve read and loved three of Nunez’s novels. I’m a third of the way into this, “a meditation on our contemporary era, as a solitary female narrator asks what it means to be alive at this complex moment in history … Humor, to be sure, is a priceless refuge. Equally vital is connection with others, who here include an adrift member of Gen Z and a spirited parrot named Eureka.” (Print proof copy)

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez [Jan. 25, Virago; has been out since November from Riverhead] I’ve read and loved three of Nunez’s novels. I’m a third of the way into this, “a meditation on our contemporary era, as a solitary female narrator asks what it means to be alive at this complex moment in history … Humor, to be sure, is a priceless refuge. Equally vital is connection with others, who here include an adrift member of Gen Z and a spirited parrot named Eureka.” (Print proof copy)

Come and Get It by Kiley Reid [Jan. 30, Bloomsbury / Jan. 9, G.P. Putnam’s] Such a Fun Age was a surprise hit with me, so I’m keen to try her second novel, set on a college campus. “It’s 2017 at the University of Arkansas. Millie Cousins, a senior resident assistant, wants to graduate, get a job, and buy a house. So when Agatha Paul, a [lesbian] visiting professor and writer, offers Millie an easy yet unusual opportunity, she jumps at the chance. But Millie’s starry-eyed hustle becomes jeopardised by odd new friends, vengeful dorm pranks and illicit intrigue.” (NetGalley download / public library reservation)

Come and Get It by Kiley Reid [Jan. 30, Bloomsbury / Jan. 9, G.P. Putnam’s] Such a Fun Age was a surprise hit with me, so I’m keen to try her second novel, set on a college campus. “It’s 2017 at the University of Arkansas. Millie Cousins, a senior resident assistant, wants to graduate, get a job, and buy a house. So when Agatha Paul, a [lesbian] visiting professor and writer, offers Millie an easy yet unusual opportunity, she jumps at the chance. But Millie’s starry-eyed hustle becomes jeopardised by odd new friends, vengeful dorm pranks and illicit intrigue.” (NetGalley download / public library reservation)

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar [March 7, Picador /Jan. 23, Knopf] I’ve read Akbar’s two full-length poetry collections and particularly admired Pilgrim Bell. His debut novel sounds kind of unhinged, but I figure it’s worth a try. “When Cyrus’s obsession with the lives of the martyrs – Bobby Sands, Joan of Arc – leads him to a chance encounter with a dying artist, he finds himself drawn towards the mysteries of an uncle who rode through Iranian battlefields dressed as the Angel of Death; and toward his [late] mother, who may not have been who or what she seemed.” (NetGalley download)

Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar [March 7, Picador /Jan. 23, Knopf] I’ve read Akbar’s two full-length poetry collections and particularly admired Pilgrim Bell. His debut novel sounds kind of unhinged, but I figure it’s worth a try. “When Cyrus’s obsession with the lives of the martyrs – Bobby Sands, Joan of Arc – leads him to a chance encounter with a dying artist, he finds himself drawn towards the mysteries of an uncle who rode through Iranian battlefields dressed as the Angel of Death; and toward his [late] mother, who may not have been who or what she seemed.” (NetGalley download)

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko [March 7, Dialogue Books / March 19, Riverhead] Ko’s debut, The Leavers, was a favourite of mine from 2018, so it was great to hear that she is coming out with a new book. “Moving from the predigital 1980s to the art and tech subcultures of the 1990s to a strikingly imagined portrait of the 2040s, Memory Piece is an innovative and audacious story of three lifelong [female, Asian American] friends as they strive to build satisfying lives in a world that turns out to be radically different from the one they were promised.”

Memory Piece by Lisa Ko [March 7, Dialogue Books / March 19, Riverhead] Ko’s debut, The Leavers, was a favourite of mine from 2018, so it was great to hear that she is coming out with a new book. “Moving from the predigital 1980s to the art and tech subcultures of the 1990s to a strikingly imagined portrait of the 2040s, Memory Piece is an innovative and audacious story of three lifelong [female, Asian American] friends as they strive to build satisfying lives in a world that turns out to be radically different from the one they were promised.”

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 23, Random House] I’m reading this for an early Shelf Awareness review. It’s fairly breezy but enjoyable, with an expected foodie theme plus hints of magic but also trauma from the protagonist’s upbringing. “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” (PDF review copy)

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 23, Random House] I’m reading this for an early Shelf Awareness review. It’s fairly breezy but enjoyable, with an expected foodie theme plus hints of magic but also trauma from the protagonist’s upbringing. “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.” (PDF review copy)

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry [May 2, Jonathan Cape / May 7, Mariner Books] “Thomas Hart and Grace Macauley are fellow worshippers at the Bethesda Baptist chapel in the small Essex town of Aldleigh. Though separated in age by three decades, the pair are kindred spirits – torn between their commitment to religion and their desire for more. But their friendship is threatened by the arrival of love.” Sounds a lot like The Essex Serpent (which is a very good thing) but with astronomy. (Print proof copy)

Enlightenment by Sarah Perry [May 2, Jonathan Cape / May 7, Mariner Books] “Thomas Hart and Grace Macauley are fellow worshippers at the Bethesda Baptist chapel in the small Essex town of Aldleigh. Though separated in age by three decades, the pair are kindred spirits – torn between their commitment to religion and their desire for more. But their friendship is threatened by the arrival of love.” Sounds a lot like The Essex Serpent (which is a very good thing) but with astronomy. (Print proof copy)

The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley [May 7, Sceptre/Avid Reader Press] “A time travel romance, a speculative spy thriller, a workplace comedy, and an ingeniously constructed exploration of the nature of truth and power and the potential for love to change it. In the near future, a civil servant is offered the salary of her dreams and is, shortly afterward, told what project she’ll be working on. A recently established government ministry is gathering ‘expats’ from across history to establish whether time travel is feasible—for the body, but also for the fabric of space-time.” Promises to be zany and fun.

The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley [May 7, Sceptre/Avid Reader Press] “A time travel romance, a speculative spy thriller, a workplace comedy, and an ingeniously constructed exploration of the nature of truth and power and the potential for love to change it. In the near future, a civil servant is offered the salary of her dreams and is, shortly afterward, told what project she’ll be working on. A recently established government ministry is gathering ‘expats’ from across history to establish whether time travel is feasible—for the body, but also for the fabric of space-time.” Promises to be zany and fun.

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [May 21, Virago/Riverhead] I loved The Incendiaries and look forward to reading this next month for an early Shelf Awareness review. “At a lavish party in the hills outside of San Francisco, Jin Han meets Lidija Jung and nothing will ever be the same for either woman. A brilliant, young photographer, Jin is at a crossroads in her work, in her marriage to college sweetheart Phillip, in who she is and who she wants to be. Lidija is a glamorous, injured world-class ballerina on hiatus from her ballet company under mysterious circumstances. Drawn to each other by their intense artistic drives, the two women talk all night.” Bisexual rep from Kwon. (PDF review copy)

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [May 21, Virago/Riverhead] I loved The Incendiaries and look forward to reading this next month for an early Shelf Awareness review. “At a lavish party in the hills outside of San Francisco, Jin Han meets Lidija Jung and nothing will ever be the same for either woman. A brilliant, young photographer, Jin is at a crossroads in her work, in her marriage to college sweetheart Phillip, in who she is and who she wants to be. Lidija is a glamorous, injured world-class ballerina on hiatus from her ballet company under mysterious circumstances. Drawn to each other by their intense artistic drives, the two women talk all night.” Bisexual rep from Kwon. (PDF review copy)

Nonfiction

Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller [April 9, Grove Press] Fuller is one of the best memoirists out there (Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and Leaving Before the Rains Come), and I read pretty much every bereavement memoir I can get my hands on anyway. “It’s midsummer in Wyoming and Alexandra is barely hanging on. Grieving her father and pining for her home country of Zimbabwe, reeling from a midlife breakup, freshly sober and piecing her way uncertainly through a volatile new relationship with a younger woman, Alexandra vows to get herself back on even keel. And then – suddenly and incomprehensibly – her son Fi, at 21 years old, dies in his sleep.” (PDF review copy)

Fi: A Memoir of My Son by Alexandra Fuller [April 9, Grove Press] Fuller is one of the best memoirists out there (Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and Leaving Before the Rains Come), and I read pretty much every bereavement memoir I can get my hands on anyway. “It’s midsummer in Wyoming and Alexandra is barely hanging on. Grieving her father and pining for her home country of Zimbabwe, reeling from a midlife breakup, freshly sober and piecing her way uncertainly through a volatile new relationship with a younger woman, Alexandra vows to get herself back on even keel. And then – suddenly and incomprehensibly – her son Fi, at 21 years old, dies in his sleep.” (PDF review copy)

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie [June 13, Sort Of Books] Thanks to Paul (I link to his list below) for letting me know about this one. I’ll read anything Kathleen Jamie writes. “Cairn: A marker on open land, a memorial, a viewpoint shared by strangers. For the last five years … Kathleen Jamie has been turning her attention to a new form of writing: micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments. Placed together, like the stones of a wayside cairn, they mark a changing psychic and physical landscape.” Which leads nicely into…

Cairn by Kathleen Jamie [June 13, Sort Of Books] Thanks to Paul (I link to his list below) for letting me know about this one. I’ll read anything Kathleen Jamie writes. “Cairn: A marker on open land, a memorial, a viewpoint shared by strangers. For the last five years … Kathleen Jamie has been turning her attention to a new form of writing: micro-essays, prose poems, notes and fragments. Placed together, like the stones of a wayside cairn, they mark a changing psychic and physical landscape.” Which leads nicely into…

Poetry

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt [Jan. 11, Jonathan Cape] Hewitt’s debut collection, Tongues of Fire, was brilliant. This sounds like more of the same: “these poems forge their own unique path through the landscape. … Following the reciprocal relationship between queer sexuality and the natural world that he explored in [his previous book, the poet conjures us here into a trance: a deep delirium of hypnotic, hectic rapture where everything is called into question, until a union is finally achieved – a union in nature, with nature.”

Rapture’s Road by Seán Hewitt [Jan. 11, Jonathan Cape] Hewitt’s debut collection, Tongues of Fire, was brilliant. This sounds like more of the same: “these poems forge their own unique path through the landscape. … Following the reciprocal relationship between queer sexuality and the natural world that he explored in [his previous book, the poet conjures us here into a trance: a deep delirium of hypnotic, hectic rapture where everything is called into question, until a union is finally achieved – a union in nature, with nature.”

Other lists for more ideas:

Electric Lit (all by women of color, as chosen by R.O. Kwon)

Kate – we overlap on a couple of our picks

Laura – we overlap on a few of our picks

Paul (mostly nonfiction)

What catches your eye here? What other 2024 titles do I need to know about?

R.I.P. Reads for Halloween: Ashworth, Bazterrica, Hill, Machado & More

I don’t often read anything that could be classed as suspense or horror, so the R.I.P. challenge is a fun excuse to dip a toe into these genres each year. This year I have an eerie relationship study, a dystopian scenario where cannibalism has become the norm, some traditional ghost stories old and new, and a bonus story encountered in an unrelated anthology.

Ghosted: A Love Story by Jenn Ashworth (2021)

Laurie’s life is thrown off kilter when, after they’ve been together 15 years, her husband Mark disappears one day, taking nothing with him. She continues in her job as a cleaner on a university campus in northwest England. After work she visits her father, who is suffering from dementia, and his Ukrainian carer Olena. In general, she pretends that nothing has happened, caring little how odd it will appear that she didn’t call the police until Mark had been gone for five weeks. Despite her obsession with true crime podcasts, she can’t seem to imagine that anything untoward has happened to him. What happened to Mark, and what’s with that spooky spare room in their flat that Laurie won’t let anyone enter?

If you find unreliable narrators delicious, you’re in the right place. The mood is confessional, yet Laurie is anything but confiding. Occasionally she apologizes for her behaviour: “I realise this does not sound very sane” is one of her concessions to readers’ rationality. So her drinking problem doesn’t become evident until nearly halfway through, and a bombshell is still to come. It’s the key to understanding our protagonist and why she’s acted this way.

If you find unreliable narrators delicious, you’re in the right place. The mood is confessional, yet Laurie is anything but confiding. Occasionally she apologizes for her behaviour: “I realise this does not sound very sane” is one of her concessions to readers’ rationality. So her drinking problem doesn’t become evident until nearly halfway through, and a bombshell is still to come. It’s the key to understanding our protagonist and why she’s acted this way.

Ghosted wasn’t what I expected. Its air of supernatural menace mellows; what is to be feared is much more ordinary. The subtitle should have been more of a clue for me. I appreciated the working class, northern setting (not often represented; Ashworth is up for this year’s Portico Prize) and the unusual relationships Laurie has with Olena, as well as with co-worker Eddie and neighbour Katrina. Reminiscent of Jo Baker’s The Body Lies and Sue Miller’s Monogamy, this story of a storm-tossed marriage was a solid introduction to Ashworth’s fiction – this is her fifth novel – but I’m not sure the payoff lived up to that amazing cover.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Tender Is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica (2017; 2020)

[Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses]

This sledgehammer of a short Argentinian novel has a simple premise: not long ago, animals were found to be infected with a virus that made them toxic to humans. During the euphemistic “Transition,” all domesticated and herd animals were killed and the roles they once held began to be filled by humans – hunted, sacrificed, butchered, scavenged, cooked and eaten. A whole gastronomic culture quickly developed around cannibalism.

This sledgehammer of a short Argentinian novel has a simple premise: not long ago, animals were found to be infected with a virus that made them toxic to humans. During the euphemistic “Transition,” all domesticated and herd animals were killed and the roles they once held began to be filled by humans – hunted, sacrificed, butchered, scavenged, cooked and eaten. A whole gastronomic culture quickly developed around cannibalism.

Marcos is our guide to this horrific near-future world. Although he works in a slaughterhouse, he’s still uneasy with some aspects of the arrangement. The standard terminology is an attempt at dispassion: the “heads” are “processed” for their “meat.” Smarting from the loss of his baby son and with his father in a nursing home, Marcos still has enough compassion that when he’s gifted a high-quality female he views her as a person rather than potential cuts of flesh. His decisions from here on will call into question his loyalty to the new system.

I wondered if there would come a point where I was no longer physically able to keep reading. But it’s fiendishly clever how the book beckons you into analogical situations and then forces you to face up to cold truths. It’s impossible to avoid the animal-rights message (in a book full of gruesome scenes, the one that involves animals somehow hits hardest), but I also thought a lot about how human castes might work – dooming some to muteness, breeding and commodification, while others are the privileged overseers granted peaceful ends. Bazterrica also conflates sex and death in uncomfortable ways. In one sense, this was not easy to read. But in another, I was morbidly compelled to turn the pages. Brutal but brilliant stuff. (Public library/Edelweiss)

Fear: Tales of Terror and Suspense, selected by Roald Dahl (2017)

I reviewed the five female-penned ghost stories for R.I.P. back in 2019. This year I picked out another five, leaving a final four for another year. (Review copy)

I reviewed the five female-penned ghost stories for R.I.P. back in 2019. This year I picked out another five, leaving a final four for another year. (Review copy)

“W.S.” by L.P. Hartley: The only thing I’ve read of Hartley’s besides The Go-Between. Novelist Walter Streeter is confronted by one of his characters, to whom he gave the same initials. What’s real and what’s only going on in his head? Perfectly plotted and delicious.

“In the Tube” by E.F. Benson: The concept of time is called into question when someone witnesses a suicide on the London Underground some days before it could actually have happened. All recounted as a retrospective tale. Believably uncanny.

“Elias and the Draug” by Jonas Lie: A sea monster and ghost ship plague Norwegian fishermen.

“The Ghost of a Hand” by J. Sheridan Le Fanu: A disembodied hand wreaks havoc in an eighteenth-century household.

“On the Brighton Road” by Richard Middleton: A tramp meets an ill boy on a road in the Sussex Downs. A classic ghost story that pivots on its final line.

The Small Hand: A Ghost Story by Susan Hill (2010)

This was my fourth of Hill’s classic ghost stories, after The Woman in Black, The Man in the Picture and Dolly. They’re always concise and so fluently written that the storytelling voice feels effortless. I wondered if this one might have been inspired by “The Ghost of a Hand” (above). It doesn’t feature a disembodied hand, per se, but the presence of a young boy who slips his hand into antiquarian book dealer Adam Snow’s when he stops at an abandoned house in the English countryside, and again when he goes to a French monastery to purchase a Shakespeare First Folio. Each time, Adam feels the ghost is pulling him to throw himself into a pond. When Adam confides in the monks and in his brother, he gets different advice. A pleasant and very quick read, if a little predictable. (Free from a neighbour)

This was my fourth of Hill’s classic ghost stories, after The Woman in Black, The Man in the Picture and Dolly. They’re always concise and so fluently written that the storytelling voice feels effortless. I wondered if this one might have been inspired by “The Ghost of a Hand” (above). It doesn’t feature a disembodied hand, per se, but the presence of a young boy who slips his hand into antiquarian book dealer Adam Snow’s when he stops at an abandoned house in the English countryside, and again when he goes to a French monastery to purchase a Shakespeare First Folio. Each time, Adam feels the ghost is pulling him to throw himself into a pond. When Adam confides in the monks and in his brother, he gets different advice. A pleasant and very quick read, if a little predictable. (Free from a neighbour)

And a bonus story:

Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror” appears in Kink (2021), a short story anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. (I requested it from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Machado and Brandon Taylor.) It opens “I would never forget the night I saw Maxa decompose before me.” A seamstress, obsessed with an actress, becomes her dresser. Set in the 19th-century Parisian theatre world, this pairs queer desire and early special effects and is over-the-top sensual in the vein of Angela Carter, with hints of the sadomasochism that got it a place here.

Carmen Maria Machado’s “The Lost Performance of the High Priestess of the Temple of Horror” appears in Kink (2021), a short story anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. (I requested it from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Machado and Brandon Taylor.) It opens “I would never forget the night I saw Maxa decompose before me.” A seamstress, obsessed with an actress, becomes her dresser. Set in the 19th-century Parisian theatre world, this pairs queer desire and early special effects and is over-the-top sensual in the vein of Angela Carter, with hints of the sadomasochism that got it a place here.

Sample lines: “Women seep because they occupy the filmy gauze between the world of the living and the dead.” & “Her body blotted out the moon. She was an ambulatory garden, a beacon in a dead season, life where life should not grow.”

Also counting the short stories by Octavia E. Butler and Bradley Sides, I did some great R.I.P. reading this year! I think the book that will stick with me the most is Tender Is the Flesh.

Short Stories in September, Part II: Tove Jansson, Brandon Taylor, Eley Williams

Each September I make a special effort to read short stories, which otherwise tend to languish on my shelves and TBR unread. After my first four reviewed last week, I have another three wonderfully different collections, ranging from bittersweet children’s fantasy in translation to offbeat, wordplay-filled love notes via linked stories suffused with desire and desperation.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson (1962; 1963)

[Trans. from the Swedish by Thomas Warburton]

I only discovered the Moomins in my late twenties, but soon fell in love with the quirky charm of Jansson’s characters and their often melancholy musings. Her stories feel like they can be read on multiple levels, with younger readers delighting in the bizarre creations and older ones sensing the pensiveness behind their quests. There are magical events here: Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter is enough to bring a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings—

I only discovered the Moomins in my late twenties, but soon fell in love with the quirky charm of Jansson’s characters and their often melancholy musings. Her stories feel like they can be read on multiple levels, with younger readers delighting in the bizarre creations and older ones sensing the pensiveness behind their quests. There are magical events here: Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter is enough to bring a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings—

“we are so very small and insignificant, and so are our tea cakes and carpets and all those things, you know, and still they’re important, but always they’re threatened by mercilessness…”

—but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy:

“the strange thing was that she suddenly felt quite safe. It was a very strange feeling, and she found it indescribably nice. But what was there to worry about? The disaster had come at last.”

My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. The final story, “The Fir Tree,” is a lovely Christmas one in which the Moomins, awoken midway through their winter hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience the holiday for the first time. (Public library)

Filthy Animals by Brandon Taylor (2021)

Real Life was one of my five favourite novels of 2020, and we are in parallel fictional territory here. Lionel, the protagonist in four of the 11 stories, is similar to Wallace insomuch as both are gay African Americans at a Midwestern university who become involved with a (straight?) white guy. The main difference is that Lionel has just been released from hospital after a suicide attempt. A mathematician (rather than a biochemist like Wallace), he finds numbers soothingly precise in comparison to the muddle of his thoughts and emotions.

In the opening story, “Potluck,” he meets Charles, a dancer who’s dating Sophie, and the three of them shuffle into a kind of awkward love triangle where, as in Real Life, sex and violence are uncomfortably intertwined. It’s a recurring question in the stories, even those focused around other characters: how does tenderness relate to desire? In the throes of lust, is there room for a gentler love? The troubled teens of the title story are “always in the thick of violence. It moves through them like the Holy Ghost might.” Milton, soon to be sent to boot camp, thinks he’d like to “pry open the world, bone it, remove the ugly hardness of it all.”

In the opening story, “Potluck,” he meets Charles, a dancer who’s dating Sophie, and the three of them shuffle into a kind of awkward love triangle where, as in Real Life, sex and violence are uncomfortably intertwined. It’s a recurring question in the stories, even those focused around other characters: how does tenderness relate to desire? In the throes of lust, is there room for a gentler love? The troubled teens of the title story are “always in the thick of violence. It moves through them like the Holy Ghost might.” Milton, soon to be sent to boot camp, thinks he’d like to “pry open the world, bone it, remove the ugly hardness of it all.”

Elsewhere, young adults face a cancer diagnosis (“Mass” and “What Made Them Made You”); a babysitter is alarmed by her charge’s feral tendencies (“Little Beast”); and same-sex couples renegotiate their relationships (Simon and Hartjes in “As Though That Were Love” and Sigrid and Marta in “Anne of Cleves,” one of my favourites). While the longer Lionel/Charles/Sophie stories, “Potluck” and “Proctoring,” are probably the best and a few others didn’t make much of an impression, the whole book has an icy angst that resonates. Taylor is a confident orchestrator of scenes and conversations, and the slight detachment of the prose only magnifies his characters’ longing for vulnerability (Marta says to Sigrid before they have sex for the first time: “I’m afraid I’ll mess it up. I’m afraid you’ll see me.” To which Sigrid replies, “I see you. You’re wonderful.”). (New purchase, Forum Books)

A bonus story: “Oh, Youth” was published in Kink (2021), an anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. I requested this from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Carmen Maria Machado and Brandon Taylor. All of Taylor’s work feels of a piece, such that his various characters might be rubbing shoulders at a party – which is appropriate because the centrepiece of Real Life is an excruciating dinner party, Filthy Animals opens at a potluck, and “Oh, Youth” is set at a dinner party.

A bonus story: “Oh, Youth” was published in Kink (2021), an anthology edited by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon. I requested this from NetGalley just so I could read the stories by Carmen Maria Machado and Brandon Taylor. All of Taylor’s work feels of a piece, such that his various characters might be rubbing shoulders at a party – which is appropriate because the centrepiece of Real Life is an excruciating dinner party, Filthy Animals opens at a potluck, and “Oh, Youth” is set at a dinner party.

Grisha is here with Enid and Victor, his latest summer couple. He’s been a boytoy for hire since his architecture professor, Nate, surprised him by inviting him into his open marriage with Brigid. “His life at the time was a series of minor discomforts that accumulated like grit in a socket until rotation was no longer possible.” The liaisons are a way to fund a more luxurious lifestyle and keep himself in cigarettes.

While Real Life brought to mind Virginia Woolf, Taylor’s stories recall E.M. Forster or Thomas Mann. In other words, he’s the real deal: a blazing talent, here to stay.

Attrib. and Other Stories by Eley Williams (2017)

After enjoying her debut novel, The Liar’s Dictionary, this time last year, I was pleased to find Williams’s first book in a charity shop last year. Her stories are brief (generally under 10 pages) and 15 of the 17 are first-person narratives, often voiced by a heartbroken character looking for the words to describe their pain or woo back a departed lover. A love of etymology is patent and, as in Ali Smith’s work, the prose is enlivened by the wordplay.

After enjoying her debut novel, The Liar’s Dictionary, this time last year, I was pleased to find Williams’s first book in a charity shop last year. Her stories are brief (generally under 10 pages) and 15 of the 17 are first-person narratives, often voiced by a heartbroken character looking for the words to describe their pain or woo back a departed lover. A love of etymology is patent and, as in Ali Smith’s work, the prose is enlivened by the wordplay.

The settings range from an art gallery to a beach where a whale has washed up, and the speakers tend to have peculiar careers like an ortolan chef or a trainer of landmine-detecting rats. My favourite was probably “Synaesthete, Would Like to Meet,” whose narrator is coached through online dating by a doctor.

I found a number of the stories too similar and thin, and it’s a shame that the hedgehog featured on the cover of the U.S. edition has to embody human carelessness in “Spines,” which is otherwise one of the standouts. But the enthusiasm and liveliness of the language were enough to win me over. (Secondhand purchase from the British Red Cross shop, Hay-on-Wye – how fun, then, to find the line “Did you know Timbuktu is twinned with Hay-on-Wye?”)

I found a number of the stories too similar and thin, and it’s a shame that the hedgehog featured on the cover of the U.S. edition has to embody human carelessness in “Spines,” which is otherwise one of the standouts. But the enthusiasm and liveliness of the language were enough to win me over. (Secondhand purchase from the British Red Cross shop, Hay-on-Wye – how fun, then, to find the line “Did you know Timbuktu is twinned with Hay-on-Wye?”)

I’ll have one more set of short story reviews coming up before the end of the month, with a few other collections then spilling into October for R.I.P.

Other 2018 Superlatives and Some Early 2019 Recommendations

My Best Discoveries of the Year: Neil Ansell, James Baldwin, Janet Frame, Rohinton Mistry, Blake Morrison, Dani Shapiro, Sarah Vowell; Roald Dahl’s work for adults

The Author I Read the Most By: Anne Tyler (four novels)

My Proudest Reading Achievement: Getting through a whole Rachel Cusk book (it was my third attempt to read her).

My Proudest Reading Achievement: Getting through a whole Rachel Cusk book (it was my third attempt to read her).

The 2018 Books Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Melmoth by Sarah Perry and Normal People by Sally Rooney

The Year’s Biggest Disappointments: The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa and Sabrina by Nick Drnaso

The Funniest Books I Read This Year: Fox 8 by George Saunders and Calypso by David Sedaris

The Funniest Books I Read This Year: Fox 8 by George Saunders and Calypso by David Sedaris

Books that Made Me Cry: Leaving Before the Rains Come by Alexandra Fuller and The Long Goodbye by Meghan O’Rourke

The Downright Strangest Books I Read This Year: The Bus on Thursday by Sheila Barrett, The Pisces by Melissa Broder and I Love Dick by Chris Kraus

The Downright Strangest Books I Read This Year: The Bus on Thursday by Sheila Barrett, The Pisces by Melissa Broder and I Love Dick by Chris Kraus

The Debut Authors Whose Next Work I’m Most Looking Forward To: Julie Buntin, Lisa Ko and R.O. Kwon

The Best First Line of the Year: “Dust and ashes though I am, I sleep the sleep of angels.” (from The Western Wind by Samantha Harvey)

Some Early 2019 Recommendations

(in release date order)

Book Love by Debbie Tung: Bookworms will get a real kick out of these cartoons, which capture everyday moments in the life of a book-obsessed young woman (perpetually in hoodie and ponytail). She reads anything, anytime, anywhere. Even though she has piles of books staring her in the face everywhere she looks, she can never resist a trip to the bookstore or library. The very idea of culling her books or finding herself short of reading material makes her panic, and she makes a friend sign a written agreement before he can borrow one of her books. Her partner and friends think she’s batty, but she doesn’t care. I found the content a little bit repetitive and the drawing style not particularly distinguished, but Tung gets the bibliophile’s psyche just right. (Out January 1.)

Book Love by Debbie Tung: Bookworms will get a real kick out of these cartoons, which capture everyday moments in the life of a book-obsessed young woman (perpetually in hoodie and ponytail). She reads anything, anytime, anywhere. Even though she has piles of books staring her in the face everywhere she looks, she can never resist a trip to the bookstore or library. The very idea of culling her books or finding herself short of reading material makes her panic, and she makes a friend sign a written agreement before he can borrow one of her books. Her partner and friends think she’s batty, but she doesn’t care. I found the content a little bit repetitive and the drawing style not particularly distinguished, but Tung gets the bibliophile’s psyche just right. (Out January 1.)

When Death Becomes Life: Notes from a Transplant Surgeon by Joshua D. Mezrich: In this debut memoir a surgeon surveys the history of organ transplantation, recalling his own medical education and the special patients he’s met along the way. In the 1940s and 1950s patient after patient was lost to rejection of the transplanted organ, post-surgery infection, or hemorrhaging. Mezrich marvels at how few decades passed between transplantation seeming like something out of a science-fiction future and becoming a commonplace procedure. His aim is to never lose his sense of wonder at the life-saving possibilities of organ donation, and he conveys that awe to readers through his descriptions of a typical procedure. One day I will likely need a donated kidney to save my life. How grateful I am to live at a time when this is a possibility. (Out January 15.)

When Death Becomes Life: Notes from a Transplant Surgeon by Joshua D. Mezrich: In this debut memoir a surgeon surveys the history of organ transplantation, recalling his own medical education and the special patients he’s met along the way. In the 1940s and 1950s patient after patient was lost to rejection of the transplanted organ, post-surgery infection, or hemorrhaging. Mezrich marvels at how few decades passed between transplantation seeming like something out of a science-fiction future and becoming a commonplace procedure. His aim is to never lose his sense of wonder at the life-saving possibilities of organ donation, and he conveys that awe to readers through his descriptions of a typical procedure. One day I will likely need a donated kidney to save my life. How grateful I am to live at a time when this is a possibility. (Out January 15.)

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love by Dani Shapiro: Shapiro was used to strangers’ comments about her blond hair and blue eyes. How could it be that she was an Orthodox Jew? people wondered. It never occurred to her that there was any truth to these hurtful jokes. On a whim, in her fifties, she joined her husband in sending off a DNA test kit. It came back with alarming results. Within 36 hours of starting research into her origins, Shapiro had found her biological father, a sperm donor whom she calls Dr. Ben Walden, and in the year that followed, their families carefully built up a relationship. The whole experience was memoirist’s gold, for sure. This is a moving account of her emotional state as she pondered her identity and what her sense of family would be in the future. (Out January 15.)

Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love by Dani Shapiro: Shapiro was used to strangers’ comments about her blond hair and blue eyes. How could it be that she was an Orthodox Jew? people wondered. It never occurred to her that there was any truth to these hurtful jokes. On a whim, in her fifties, she joined her husband in sending off a DNA test kit. It came back with alarming results. Within 36 hours of starting research into her origins, Shapiro had found her biological father, a sperm donor whom she calls Dr. Ben Walden, and in the year that followed, their families carefully built up a relationship. The whole experience was memoirist’s gold, for sure. This is a moving account of her emotional state as she pondered her identity and what her sense of family would be in the future. (Out January 15.)

Constellations: Reflections from Life by Sinéad Gleeson: Perfect for fans of I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell, this is a set of trenchant autobiographical essays about being in a female body, especially one wracked by pain. As a child Gleeson had arthritis that weakened her hip bones, and eventually she had to have a total hip replacement. She ranges from the seemingly trivial to life-and-death matters as she writes about hairstyles, blood types, pregnancy, the abortion debate in Ireland and having a rare type of leukemia. In the tradition of Virginia Woolf, Frida Kahlo and Susan Sontag, Gleeson turns pain into art, particularly in a set of 20 poems based on the McGill Pain Index. The book feels timely and is inventive in how it brings together disparate topics to explore the possibilities and limitations of women’s bodies. (Out April 4.)

Constellations: Reflections from Life by Sinéad Gleeson: Perfect for fans of I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell, this is a set of trenchant autobiographical essays about being in a female body, especially one wracked by pain. As a child Gleeson had arthritis that weakened her hip bones, and eventually she had to have a total hip replacement. She ranges from the seemingly trivial to life-and-death matters as she writes about hairstyles, blood types, pregnancy, the abortion debate in Ireland and having a rare type of leukemia. In the tradition of Virginia Woolf, Frida Kahlo and Susan Sontag, Gleeson turns pain into art, particularly in a set of 20 poems based on the McGill Pain Index. The book feels timely and is inventive in how it brings together disparate topics to explore the possibilities and limitations of women’s bodies. (Out April 4.)

The Hot Young Widows Club: Lessons on Survival from the Front Lines of Grief by Nora McInerny: In June 2016 I read It’s Okay to Laugh (Crying Is Cool Too), McInerny’s memoir about losing her father and her husband to cancer and her second child to a miscarriage – all within a few weeks – when she was 31. In this short book, an expansion of her TED talk, she argues that we are all incompetent when it comes to grief. There’s no rule book for how to do it well or how to help other people who are experiencing a bereavement, and comparing one loss to another doesn’t help anyone. I especially appreciated her rundown of the difference between pity and true empathy. “Pity keeps our hearts closed up, locked away. Empathy opens our heart up to the possibility that the pain of others could one day be our own pain.” (Out April 30.)

The Hot Young Widows Club: Lessons on Survival from the Front Lines of Grief by Nora McInerny: In June 2016 I read It’s Okay to Laugh (Crying Is Cool Too), McInerny’s memoir about losing her father and her husband to cancer and her second child to a miscarriage – all within a few weeks – when she was 31. In this short book, an expansion of her TED talk, she argues that we are all incompetent when it comes to grief. There’s no rule book for how to do it well or how to help other people who are experiencing a bereavement, and comparing one loss to another doesn’t help anyone. I especially appreciated her rundown of the difference between pity and true empathy. “Pity keeps our hearts closed up, locked away. Empathy opens our heart up to the possibility that the pain of others could one day be our own pain.” (Out April 30.)

Coming tomorrow: Library Checkout & Final statistics for the year

Have you read any 2019 releases you can recommend?

Best Fiction & Poetry of 2018

Below I’ve chosen my top 12 fiction releases from 2018 (eight of them happen to be by women!). Many of these books have already featured on my blog in some way over the course of the year. To keep things simple, as with my nonfiction selections, I’m limiting myself to two sentences per title: the first is a potted summary; the second tells you why you should read it. I’ve also highlighted my three favorites from the year’s poetry releases.

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes: From the Iraq War protests to the Occupy movement in New York City, we follow antiheroine Gael Foess as she tries to get her brother’s art recognized. This debut novel is a potent reminder that money and skills don’t get distributed fairly in this life.

Orchid & the Wasp by Caoilinn Hughes: From the Iraq War protests to the Occupy movement in New York City, we follow antiheroine Gael Foess as she tries to get her brother’s art recognized. This debut novel is a potent reminder that money and skills don’t get distributed fairly in this life.

Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller: Fuller’s third novel tells the suspenseful story of the profligate summer of 1969 spent at a dilapidated English country house. The characters and atmosphere are top-notch; this is an absorbing, satisfying novel to swallow down in big gulps.

Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller: Fuller’s third novel tells the suspenseful story of the profligate summer of 1969 spent at a dilapidated English country house. The characters and atmosphere are top-notch; this is an absorbing, satisfying novel to swallow down in big gulps.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: It may be a familiar story – a May–December romance that fizzles out – but, as Paul believes, we only really get one love story, the defining story of our lives. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes: It may be a familiar story – a May–December romance that fizzles out – but, as Paul believes, we only really get one love story, the defining story of our lives. The picture of romantic youth shading into cynical but still hopeful middle age really resonates, as do the themes of unconventionality, memory, addiction and pity.

The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Summer 1969: four young siblings escape a sweltering New York City morning by visiting a fortune teller who can tell you the day you’ll die; in the decades that follow, they have to decide what to do with this advance knowledge: will it spur them to live courageous lives, or drive them to desperation? This compelling family story lives up to the hype.

The Immortalists by Chloe Benjamin: Summer 1969: four young siblings escape a sweltering New York City morning by visiting a fortune teller who can tell you the day you’ll die; in the decades that follow, they have to decide what to do with this advance knowledge: will it spur them to live courageous lives, or drive them to desperation? This compelling family story lives up to the hype.

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. This would make a great book club pick: I ached for all the main characters in their impossible situation; there’s a lot to probe about their personalities and motivations, and about how they reveal or disguise themselves through their narration and letters.

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones: Roy and Celestial only get a year of happy marriage before he’s falsely accused of rape and sentenced to 12 years in prison in Louisiana. This would make a great book club pick: I ached for all the main characters in their impossible situation; there’s a lot to probe about their personalities and motivations, and about how they reveal or disguise themselves through their narration and letters.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is an Italian teacher; as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he’d follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts, but along the way something went wrong. This is a rewarding novel about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman: Charles “Pinch” Bavinsky is an Italian teacher; as a boy in Rome in the 1950s–60s he believed he’d follow in the footsteps of his sculptor mother and his moderately famous father, Bear Bavinsky, who paints close-ups of body parts, but along the way something went wrong. This is a rewarding novel about the desperation to please, or perhaps exceed, one’s parents and the legacy of artists in a fickle market.

The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon: A sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word.

The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon: A sophisticated, unsettling debut novel about faith and its aftermath, fractured through the experience of three people coming to terms with painful circumstances. Kwon spent 10 years writing this book, and that time and diligence come through in how carefully honed the prose is: such precise images; not a single excess word.

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver’s bold eighth novel has a dual timeline that compares the America of the 1870s and the recent past and finds that they are linked by distrust and displacement. There’s so much going on that it feels like it encompasses all of human life; it’s by no means a subtle book, but it’s an important one for our time, with many issues worth pondering and discussing.

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver: Kingsolver’s bold eighth novel has a dual timeline that compares the America of the 1870s and the recent past and finds that they are linked by distrust and displacement. There’s so much going on that it feels like it encompasses all of human life; it’s by no means a subtle book, but it’s an important one for our time, with many issues worth pondering and discussing.

Southernmost by Silas House: In House’s sixth novel, a Tennessee preacher’s family life falls apart when he accepts a gay couple into his church. We go on a long journey with Asher Sharp: not just a literal road trip from Tennessee to Florida, but also a spiritual passage from judgment to grace in this beautiful, quietly moving novel of redemption and openness to what life might teach us.

Southernmost by Silas House: In House’s sixth novel, a Tennessee preacher’s family life falls apart when he accepts a gay couple into his church. We go on a long journey with Asher Sharp: not just a literal road trip from Tennessee to Florida, but also a spiritual passage from judgment to grace in this beautiful, quietly moving novel of redemption and openness to what life might teach us.

Little by Edward Carey: This is a deliciously macabre, Dickensian novel about Madame Tussaud, who started life as Anne Marie Grosholtz in Switzerland in 1761. From a former monkey house to the Versailles palace and back, Marie must tread carefully as the French Revolution advances and a desire for wax heads is replaced by that for decapitated ones.

Little by Edward Carey: This is a deliciously macabre, Dickensian novel about Madame Tussaud, who started life as Anne Marie Grosholtz in Switzerland in 1761. From a former monkey house to the Versailles palace and back, Marie must tread carefully as the French Revolution advances and a desire for wax heads is replaced by that for decapitated ones.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti: Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti: Chance, inheritance, and choice vie for pride of place in this relentless, audacious inquiry into the purpose of a woman’s life. The book encapsulates nearly every thought that has gone through my mind over the last decade as I’ve faced the intractable question of whether to have children.

Florida by Lauren Groff: There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout these 11 short stories, with violent storms reminding the characters of an uncaring universe, falling-apart relationships, and the threat of environmental catastrophe. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant; any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece. (I never would have predicted that a short story collection would be my favorite fiction read of the year!)

Florida by Lauren Groff: There’s an oppressive atmosphere throughout these 11 short stories, with violent storms reminding the characters of an uncaring universe, falling-apart relationships, and the threat of environmental catastrophe. Florida feels innovative and terrifyingly relevant; any one of its stories is a bracing read; together they form a masterpiece. (I never would have predicted that a short story collection would be my favorite fiction read of the year!)

My 2018 fiction books of the year (the ones I own in print, anyway).

Poetry selections:

-

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan: These poem-essays give fragmentary images of city life and question the notion of progress and what meaning a life leaves behind. “The Sandpit after Rain” stylishly but grimly juxtaposes her father’s death and her son’s birth.

Three Poems by Hannah Sullivan: These poem-essays give fragmentary images of city life and question the notion of progress and what meaning a life leaves behind. “The Sandpit after Rain” stylishly but grimly juxtaposes her father’s death and her son’s birth.

-

Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016 by Rafael Campo: Superb, poignant poetry about illness and the physician’s duty. A good bit of this was composed in response to the AIDS crisis; it’s remarkable how Campo wrings beauty out of clinical terminology and tragic situations.

Comfort Measures Only: New and Selected Poems, 1994–2016 by Rafael Campo: Superb, poignant poetry about illness and the physician’s duty. A good bit of this was composed in response to the AIDS crisis; it’s remarkable how Campo wrings beauty out of clinical terminology and tragic situations.

-

The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain: St. Germain’s seventh collection is in memory of her son Gray, who died of a drug overdose in 2014, aged 30. She turns her family history of alcohol and drug use into a touchpoint and affirms life’s sensual pleasures – everything from the smell of brand-new cowboy boots to luscious fruits.

The Small Door of Your Death by Sheryl St. Germain: St. Germain’s seventh collection is in memory of her son Gray, who died of a drug overdose in 2014, aged 30. She turns her family history of alcohol and drug use into a touchpoint and affirms life’s sensual pleasures – everything from the smell of brand-new cowboy boots to luscious fruits.

What were some of your top fiction (or poetry) reads of the year?

Tomorrow I’ll be naming some runners-up (both fiction and nonfiction).

Vocabulary Words I Learned from Books This Year

These are in chronological order by my reading.

- borborygmi = stomach rumblings caused by the movement of fluid and gas in the intestines

- crapula = sickness caused by excessive eating and drinking

- olm = a cave-dwelling aquatic salamander

~The Year of the Hare, Arto Paasilinna

- befurbelowed = ornamented with frills (the use seems to be peculiar to this book, as it is the example in every online dictionary!)

~The Awakening, Kate Chopin

roding = the sound produced during the mating display of snipe and woodcock, also known as drumming

roding = the sound produced during the mating display of snipe and woodcock, also known as drumming- peat hag = eroded ground from which peat has been cut

~Deep Country, Neil Ansell

- rallentando = a gradual decrease in speed

~Sight, Jessie Greengrass

- piceous = resembling pitch

~March, Geraldine Brooks

- soffit = the underside of eaves or an arch, balcony, etc.

~The Only Story, Julian Barnes

lemniscate = the infinity symbol, here used as a metaphor for the pattern of pipe smoke

lemniscate = the infinity symbol, here used as a metaphor for the pattern of pipe smoke

~The Invisible Bridge, Julie Orringer

- purfling = a decorative border

- lamingtons = sponge cake squares coated in chocolate and desiccated coconut (sounds yummy!)

~The Life and Loves of Lena Gaunt, Tracy Farr

- ocellated = having eye-shaped markings

~Red Clocks, Leni Zumas

- balloonatic (WWI slang) = a ballooning enthusiast

- skinkling = sparkling

- preludial = introductory

- claustral = confining

- baccalà = salted cod

~The Incendiaries, R. O. Kwon

(There were so many words I didn’t immediately recognize in this novel that I thought Kwon must have made them up; preludial and claustral, especially, are words I didn’t know existed but that one might have extrapolated from their noun forms.)

bronies = middle-aged male fans of My Little Pony (wow, who knew this was a thing?! I feel like I’ve gone down a rabbit hole just by Googling it.)

bronies = middle-aged male fans of My Little Pony (wow, who knew this was a thing?! I feel like I’ve gone down a rabbit hole just by Googling it.)- callipygian = having well-shaped buttocks

~Gross Anatomy, Mara Altman

- syce = someone who looks after horses; a groom (especially in India; though here it was Kenya)

- riem = a strip of rawhide or leather

- pastern = a horse’s ankle equivalent

~West with the Night, Beryl Markham

- blintering = flickering, glimmering (Scottish)

- sillion = shiny soil turned over by a plow

~The Light in the Dark: A Winter Journal, Horatio Clare

- whiffet = a small, young or unimportant person

~Ladder of Years, Anne Tyler

- trilliant = a triangular gemstone cut

- cabochon = a gemstone that’s polished but not faceted

- blirt = a gust of wind and rain (but here used as a verb: “Coldness blirted over her”)

- contumacious = stubbornly disobedient

~Four Bare Legs in a Bed, Helen Simpson

xeric = very dry (usually describes a habitat, but used here for a person’s manner)

xeric = very dry (usually describes a habitat, but used here for a person’s manner)

~Unsheltered, Barbara Kingsolver

- twitten = a narrow passage between two walls or hedges (Sussex dialect – Marshall is based near Brighton)

~The Power of Dog, Andrew Marshall

- swither (Scottish) = to be uncertain as to which course of action to take

- strathspey = a dance tune, a slow reel

~Stargazing, Peter Hill

- citole = a medieval fiddle

- naker = a kettledrum

- amice = a liturgical vestment that resembles a cape

~The Western Wind, Samantha Harvey

pareidolia = seeing faces in things, an evolutionary adaptation (check out @FacesPics on Twitter!)

pareidolia = seeing faces in things, an evolutionary adaptation (check out @FacesPics on Twitter!)

~The Overstory, Richard Powers

Have you learned any new vocabulary words recently?

How likely am I to use any of these words in the next year?

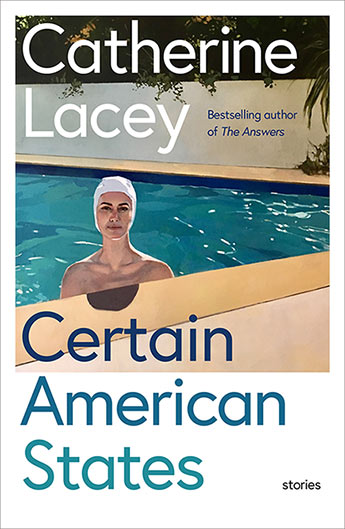

Certain American States: Stories by Catherine Lacey

The loneliness of certain American states is enough to kill a person if you look too closely

I come from a certain American state: Maryland. Before I first came to England 15 years ago, I’d never lived anywhere else. It’s the ninth-smallest state but has a little bit of everything – mountains, lakes and farmland; coast and bayfront; rough cities and pleasant towns; plus proximity to the nation’s capital – which is why it’s nicknamed “America in Miniature.” Brits say Merry-Land (it’s more like the name Marilyn, with a faint D on the end) and more than once when asked where I’m from I’ve heard in reply,“like the cookies?” No, not like the cookies!

Anyway, the characters in Catherine Lacey’s short story collection move through various states – Texas, North Dakota, Virginia, Montana – but the focus is more on their emotional states. Ten of the 12 stories are in the first person, giving readers a deep dive into the psyches of damaged or bereaved people. I particularly liked “ur heck box,” in which the narrator, troubled by the death of her brother and wary of her mother joining her in New York City, starts getting garbled messages from a deaf man. Whether a result of predictive text errors or mental illness, these notes on his phone echo her confusion at what’s become of her life.

Two other favorites were “Touching People,” in which a sixty-something woman takes a honeymooning couple to see her ex-husband’s grave, and “Small Differences,” about a woman who’s cat-sitting for her on-and-off boyfriend and remembers the place faith used to have in her life. Both dramatize the divide between youth and age; in the latter the cat is named Echo, a reminder that the past still resonates. Another standout is “Learning,” about a painting teacher with a crumbling house and marriage whose deadbeat college friend has become a parenting guru. (This one reminded me of Curtis Sittenfeld’s “The Prairie Wife.”)