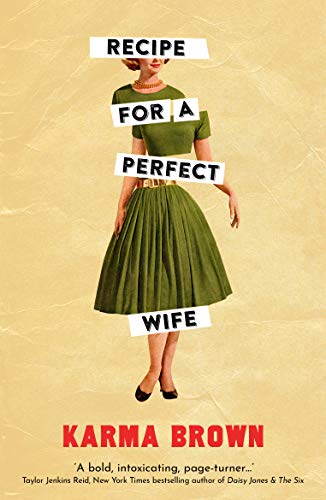

Literary Wives Club: Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown (2019)

{SPOILERS IN THIS REVIEW!}

Canadian author Karma Brown’s fifth novel features two female protagonists who lived in the same house in different decades. The dual timeline, which plays out in alternating chapters, contrasts the mid-1950s and late 2010s to ask 1) whether the situation of women has really improved and 2) if marriage is always and inevitably an oppressive force.

Nellie Murdoch loves cooking and gardening – great skills for a mid-twentieth-century housewife – but can’t stay pregnant, which provokes the anger of her abusive husband, Richard. To start with, Alice Hale can’t cook or garden for toffee and isn’t sure she wants a baby at all, but as she reads through Nellie’s unsent letters and recipes, interspersed with Ladies’ Home Journal issues in the boxes in the basement, she starts to not just admire Nellie but emulate her. She’s keeping several things from her husband Nate: she was fired from her publicist job after a pre-#MeToo scandal involving a handsy male author, she’s had an IUD fitted, and she’s made zero progress on the novel she’s supposed to be writing. But Nellie’s correspondence reveals secrets that inspire Alice to compose Recipe for a Perfect Wife.

The chapter epigraphs, mostly from period etiquette and relationship guides for young wives, provide ironic commentary on this pair of not-so-perfect marriages. Brown has us wondering how closely Alice will mirror Nellie’s trajectory (aborting her pregnancy? poisoning her husband?). There were clichéd elements, such as Richard’s adultery, glitzy New York City publishing events, Alice’s quirky-funny friend, and each woman having a kindly elderly (maternal) neighbour who looks out for her and gives her valuable advice. I felt uncomfortable with how Nellie’s mother’s suicide makes it seem like Nellie’s radical acts are borne out of inherited mental illness rather than a determination to make her own path.

Often, I felt Brown was “phoning it in,” if that phrase means anything to you. In other words, playing it safe and taking an easy and previously well-trodden path. Parallel stories like this can be clever, or can seem too simple and coincidental. However, I can affirm that the novel is highly readable and has vintage charm. I always enjoy epistolary inclusions like letters and recipes, and it was intriguing to see how Nellie uses her garden herbs and flowers for pharmaceutical uses. Our first foxglove just came into flower – eek! (Kindle purchase) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

- Being a wife does not have to mean being a housewife. (It also doesn’t have to mean being a mother, if you don’t want to be one.)

- Secrets can be lethal to a marriage. Even if they aren’t literally so, they’re a really bad idea.

This was, overall, a very bleak picture of marriage. In the 1950s strand there is a scene of marital rape – one of two I’ve read recently, and I find these particularly difficult to take. Alice’s marriage might not have blown up as dramatically, but still doesn’t appear healthy. She forced Nate to choose between her and the baby, and his job promotion in California. The fallout from that ultimatum is not going to make for a happy relationship. I almost thought that Nellie wields more power. However, both women get ahead through deception and manipulation. I think we are meant to cheer for what they achieve, and I did for Nellie’s revenge at Richard’s vileness, but Alice I found brattish and calculating.

See Kate’s, Kay’s and Naomi’s reviews, too!

Coming up next, in September: Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

Three “Love” or “Heart” Books for Valentine’s Day: Ephron, Lischer and Nin

Every year I say I’m really not a Valentine’s Day person and yet put together a themed post featuring books that have “Love” or a similar word in the title. This is the eighth year in a row, in fact (after 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023)! Today I’m looking at two classic novellas, one of them a reread and the other my first taste of a writer I’d expected more from; and a wrenching, theologically oriented bereavement memoir.

Heartburn by Nora Ephron (1983)

I’d already pulled this out for my planned reread of books published in my birth year, so it’s pleasing that it can do double duty here. I can’t say it better than my original 2013 review:

The funniest book you’ll ever read about heartbreak and betrayal, this is full of wry observations about the compromises we make to marry – and then stay married to – people who are very different from us. Ephron readily admitted that her novel is more than a little autobiographical: it’s based on the breakdown of her second marriage to investigative journalist Carl Bernstein (All the President’s Men), who had an affair with a ludicrously tall woman – one element she transferred directly into Heartburn.

Ephron’s fictional counterpart is Rachel Samstad, a New Yorker who writes cookbooks or, rather, memoirs with recipes – before that genre really took off. Seven months pregnant with her second child, she has just learned that her second husband is having an affair. What follows is her uproarious memories of life, love and failed marriages. Indeed, as Ephron reflected in a 2004 introduction, “One of the things I’m proudest of is that I managed to convert an event that seemed to me hideously tragic at the time to a comedy – and if that’s not fiction, I don’t know what is.”

As one might expect from a screenwriter, there is a cinematic – that is, vivid but not-quite-believable – quality to some of the moments: the armed robbery of Rachel’s therapy group, her accidentally flinging an onion into the audience during a cooking demonstration, her triumphant throw of a key lime pie into her husband’s face in the final scene. And yet Ephron was again drawing on experience: a friend’s therapy group was robbed at gunpoint, and she’d always filed the experience away in a mental drawer marked “Use This Someday” – “My mother taught me many things when I was growing up, but the main thing I learned from her is that everything is copy.” This is one of celebrity chef Nigella Lawson’s favorite books ever, for its mixture of recipes and rue, comfort food and folly. It’s a quick read, but a substantial feast for the emotions.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Sometimes I wonder why I bother when I can’t improve on reviews I wrote over a decade ago (see also another upcoming reread). What I would add now, without disputing any of the above, is that there’s more bitterness to the tone than I’d recalled, even though Ephron does, yes, play it for laughs. But also, some of the humour hasn’t aged well, especially where based on race/culture or sexuality. I’d forgotten that Rachel’s husband isn’t the only cheater here; pretty much every couple mentioned is currently working through the aftermath of an affair or has survived one in the past. In one of these, the wife who left for a woman is described not as a lesbian but by another word, each time, which felt unkind rather than funny.

Still, the dialogue, the scenes, the snarky self-portrayal: it all pops. This was autofiction before that was a thing, but anyone working in any genre could learn how to write readable content by studying Ephron. “‘I don’t have to make everything into a joke,’ I said. ‘I have to make everything into a story.’ … I think you often have that sense when you write – that if you can spot something in yourself and set it down on paper, you’re free of it. And you’re not, of course; you’ve just managed to set it down on paper, that’s all.” (Little Free Library)

My original rating (2013):

My rating now:

Stations of the Heart: Parting with a Son by Richard Lischer (2013)

“What we had taken to be a temporary unpleasantness had now burrowed deep into the family pulp and was gnawing us from the inside out.” Like all life writing, the bereavement memoir has two tasks: to bear witness and to make meaning. From a distance that just happens to be Mary Karr’s prescribed seven years, Lischer opens by looking back on the day when his 33-year-old son Adam called to tell him that his melanoma, successfully treated the year before, was back. Tests revealed that the cancer’s metastases were everywhere, including in his brain, and were “innumerable,” a word that haunted Lischer and his wife, their daughter, and Adam’s wife, who was pregnant with their first child.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The next few months were a Calvary of sorts, and Lischer, an emeritus professor at Duke Divinity School, draws deliberate parallels with the biblical and liturgical preparations for Good Friday that feel appropriate for this Ash Wednesday. Lischer had no problem with Adam’s late-life conversion from Protestantism to Catholicism, whose rites he followed with great piety in his final summer. He traces Adam and Jenny’s daily routines as well as his own helpless attendance at hospital appointments. Doped up on painkillers, Adam attended one last Father’s Day baseball game with him; one last Fourth of July picnic. Everyone so desperately wanted him to keep going long enough to meet his baby girl. To think that she is now a young woman and has opened all the presents Adam bought to leave behind for her first 18 birthdays.

The facts of the story are heartbreaking enough, but Lischer’s prose is a perfect match: stately, resolute and weighted with spiritual allusion, yet never morose. He approaches the documenting of his son’s too-short life with a sense of sacred duty: “I have acquired a new responsibility: I have become the interpreter of his death. God, I must do a better job. … I kissed his head and thanked him for being my son. I promised him then that his death would not ruin my life.” This memoir brought back so much about my brother-in-law’s death from brain cancer in 2015, from the “TEAM [ADAM/GARNET]” T-shirts to Adam’s sister’s remark, “I never dreamed this would be our family’s story.” We’re not alone. (Remainder book from the Bowie, Maryland Dollar Tree)

A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin (1954)

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

I’d heard Nin spoken of in the same breath as D.H. Lawrence, so thought I might similarly appreciate her because of, or despite, comically overblown symbolism around sex. I think I was also expecting something more titillating? (I guess I had this confused for Delta of Venus, her only work that would be shelved in an Erotica section.) Many have tried to make a feminist case for this novella about Sabina, an early liberated woman in New York City who has extramarital sex with four other men who appeal to her for various not particularly good reasons (the traumatized soldier whom she comforts like a mother; the exotic African drummer – “Sabina did not feel guilty for drinking of the tropics through Mambo’s body”). She herself states, “I want to trespass boundaries, erase all identifications, anything which fixes one permanently into one mould, one place without hope of change.” The most interesting aspect of the book was Sabina’s questioning of whether she inherited her promiscuity from her father (it’s tempting to read this autobiographically as Nin’s own father left the family for another woman, a foundational wound in her life).

Come on, though, “fecundated,” “fecundation” … who could take such vocabulary seriously? Or this sex writing (snort!): “only one ritual, a joyous, joyous, joyous impaling of woman on a man’s sensual mast.” I charge you to use the term “sensual mast” wherever possible in the future. (Secondhand – Oxfam, Newbury)

But hey, check out my score for the Faber Valentine’s quiz!

August Releases: Bright Fear, Uprooting, The Farmer’s Wife, Windswept

This month I have three memoirs by women, all based on a connection to land – whether gardening, farming or crofting – and a sophomore poetry collection that engages with themes of pandemic anxiety as well as crossing cultural and gender boundaries.

My August highlight:

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan

Chan’s Flèche was my favourite poetry collection of 2019. Their follow-up returns to many of the same foundational subjects: race, family, language and sexuality. But this time, the pandemic is a lens through which all is filtered. This is particularly evident in Part I, “Grief Lessons.” “London, 2020” and “Hong Kong, 2003,” on facing pages, contrast Covid-19 with SARS, the major threat when they were a teenager. People have always made assumptions about them based on their appearance or speech. At a time when Asian heritage merited extra suspicion, English was both a means of frank expression and a source of ambivalence:

“At times, English feels like the best kind of evening light. On other days, English becomes something harder, like a white shield.” (from “In the Beginning Was the Word”)

“my Chinese / face struck like the glow of a torch on a white question: / why is your English so good, the compliment uncertain / of itself.” (from “Sestina”)

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

The poems’ structure varies, with paragraphs and stanzas of different lengths and placement on the page (including, in one instance, a goblet shape). The enjambment, as you can see in lines I’ve quoted above and below, is noteworthy. Part III, “Field Notes on a Family,” reflects on the pressures of being an only child whose mother would prefer to pretend lives alone rather than with a female partner. The book ends with hope that Chan might be able to be open about their identity. The title references the paradoxical nature of the sublime, beautifully captured via the alliteration that closes “Circles”: “a commotion of coots convincing / me to withstand the quotidian tug-/of-war between terror and love.”

Although Flèche still has the edge for me, this is another excellent work I would recommend even to those wary of poetry.

Some more favourite lines, from “Ars Poetica”:

“What my mother taught me was how

to revere the light language emitted.”

“Home, my therapist suggests, is where

you don’t have to explain yourself.”

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Three land-based memoirs:

(All:  )

)

Uprooting: From the Caribbean to the Countryside – Finding Home in an English Country Garden by Marchelle Farrell

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Farmer’s Wife: My Life in Days by Helen Rebanks

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

Growing up, Rebanks started cooking for her family early on, and got a job in a café as a teenager; her mother ran their farm home as a B&B but was forgetful to the point of being neglectful. She met James at 17 and accompanied him to Oxford, where they must have been the only student couple cooking and eating proper food. This period, when she was working an office job, baking cakes for a café, and mourning the devastating foot-and-mouth disease epidemic from a distance, is most memorable. Stories from travels, her wedding, and the births of her four children are pleasant enough, yet there’s nothing to make these experiences, or the telling of them, stand out. I wouldn’t make any of the dishes; most you could find a recipe for anywhere. Eleanor Crow’s black-and-white illustrations are lovely, though.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands by Annie Worsley

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

With thanks to William Collins for the free copy for review.

Would you read one or more of these?

20 Books of Summer, 9: Search by Michelle Huneven (2022)

Now this is what I want from my summer reading: pure pleasure; lit fic full of gossip and good food; the kind of novel I was always relieved to pick up and spend time with, usually as a reward for having gotten through my daily allotment in paid-review books and some more challenging reads. The Kirkus review was appealing enough to land this a place on my Most Anticipated list last year, but the only way to get hold of a copy was to spend my Bookshop.org voucher from my sister and have her bring it over in her suitcase in December.

The setup to Search might seem niche to many: a Southern California Unitarian church undergoes a months-long process to replace its retiring senior minister via a nationwide application process. But in fact it will resonate with, and elicit chuckles from, anyone who’s had even the most fleeting brush with bureaucracy – whether serving on a committee, conducting interviews, or trying to get a unanimous decision out of three or more people – and the framing story makes it warm and engrossing.

Dana Potowski is a middle-aged restaurant critic who has just released a successful cookbook based on what she grows on her smallholding. When she’s invited to be part of an eight-member task force looking for the right next minister for Arroyo Unitarian Universalist Community Church –

a “little chugger” of a church in a small unincorporated suburb of LA … three acres of raffish gardens, an ugly sanctuary, a deliquescing Italianate mansion, a jewel-box chapel used mostly for yoga classes

– she reluctantly agrees but soon wonders whether this could be interesting fodder for a second memoir (with identifying details changed, to be sure). You’ll quickly forget about the layers of fictionalization and become immersed in the interactions between the search committee members, who are of different genders, races and generations. They range from stalwart members, including a former church president and Dana the one-time seminarian, to a Filipino American recent Evangelical defector with a husband and young children.

Like the ministerial candidates, they’re all gloriously individual. You realize, however, that most of them have agendas and preconceived ideas. The church as a whole agreed that it wanted a gifted preacher and skilled site manager, but there’s also a collective sense that it’s time for a demographic change. A woman of colour is therefore a priority after decades of white male control, but a facilitator warns: “If you’re too focused on a specific category, you could overlook the best hire for your needs. Our goal is to get beyond thinking in categories to see the whole person.” Still, fault lines develop, with the younger contingent on the panel pushing for a thirtysomething candidate and the others giving more weight to experience.

Huneven develops all of her characters through the dialogue and repartee at the search committee’s meetings, which always take place over snacks, if not full meals with cocktails. Dana is not the only gifted home cook among the bunch (a section at the end gives recipes for some of the star dishes, like “Belinda’s Preserved Lemon Chicken,” “Dana’s Seafood Chowder,” and “Jennie’s Midmorning Glory Muffins”), and she also takes turns inviting her fellow committee members out on her restaurant assignments for the paper.

I was amazed by the formality and intensity of this decision-making process: a lengthy application packet, Skype interviews, watching/reading multiple sermons by the candidates, speaking to their references, and then an entire weekend of in-person activities with each of three top contenders. It’s clear that Huneven did a lot of research about how this works. The whole thing starts out casual and fun – Dana refers to the church and minister packets as “dating profiles” – but grows increasingly momentous. Completely different worship and leadership styles are at stake. People have their favourites, and with the future of a beloved institution at stake, compromise comes to feel more like a failure of integrity.

Keep in mind, of course, that we’re getting all of it from Dana’s perspective. She sets herself up as the objective recorder, but our admiration and distrust can only be guided by hers. And she’s a very likable narrator: intelligent and quick-witted, fond of gardening, passionate about food and spirituality, comfortable in her quiet life with her Jewish husband and her dog and donkeys. It’s possible not everyone will relate to her, or read meal plans and sermon transcripts as raptly, as I did. At the same time as I was totally absorbed in the narrative, I was also mentally transported to churches and pastors past, to petty dramas the ministers in my family have navigated, to the one Unitarian service I attended in Santa Fe in the summer of 2005… For me, this had it all. Both light and consequential; nostalgic and resolute about the future; frustrated with yet tender towards humanity. Delicious! I’ll seek out more by Huneven.

(New purchase with birthday money)

20 Books of Summer, 1: Small Fires by Rebecca May Johnson

So far I’m sticking to my vague plan and reading foodie lit, like it’s 2020 all over again. At the same time, I’m tackling a few books that I received as review copies last year but that have been on my set-aside pile for longer than I’d like to admit. Later in the summer I’ll branch out from the food theme, but always focusing on books I own and have been meaning to read.

Without further ado, my first of 20 Books of Summer:

Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson (2022)

“I tried to write about cooking, but I wrote a hot red epic.”

Johnson’s debut is a hybrid work, as much a feminist essay collection as it is a memoir about the role that cooking has played in her life. She chooses to interpret apron strings erotically, such that the preparation of meals is not gendered drudgery or oppression but an act of self-care and love for others.

“The kitchen is a space for theorizing!”

While completing a PhD on the reception of The Odyssey and its translation history, Johnson began to think about dishes as translations, or even performances, of a recipe. In two central chapters, “Hot Red Epic” and “Tracing the Sauce Text,” she reckons that she has cooked the same fresh Italian tomato sauce, with nearly infinite small variations, a thousand times over ten years. Where she lived, what she looked like, who she cooked for: so many external details changed, but this most improvisational of dishes stayed the same.

Just a peek at the authors cited in her bibliography – not just the expected subjects like MFK Fisher and Nigella Lawson but also Goethe, Lorde, Plath, Stein, Weil, Winnicott – gives you an idea of how wide-ranging and academically oriented the book is, delving into the psychology of cooking and eating. Oh yes, there will be Freudian sausages. There are also her own recipes, of a sort: one is a personal prose piece (“Bad News Potatoes”) and another is in poetic notation, beginning “I made Mrs Beeton’s / recipe for frying sausages”.

“The recipe is an epic without a hero.”

I particularly enjoyed the essay “Again and Again, There Is That You,” in which Johnson determinedly if chaotically cooks a three-course meal for someone who might be a lover. The mixture of genres and styles is inventive, but a bit strange; my taste would call for more autobiographical material and less theory. The most similar work I’ve read is Recipe by Lynn Z. Bloom, which likewise pulled in some seemingly off-topic strands. I’d be likely to recommend Small Fires to readers of Supper Club.

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the free copy for review.

Two for #NovNov22 and #NonFicNov: Recipe and Shameless

Contrary to my usual habit of leaving new books on the shelf for years before actually reading them, these two are ones I just got as birthday gifts last month. They were great choices from my wish list from my best friend and reflect our mutual interests (foodie lit) and experiences (ex-Evangelicals raised in the Church).

Recipe by Lynn Z. Bloom (2022)

This is part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series of short nonfiction works (I’ve only read a few of the other releases, but I’d also recommend Fat by Hanne Blank). Bloom, an esteemed academic based in Connecticut, envisions a recipe as being like a jazz piece: it arises from a clear tradition, yet offers a lot of scope for creativity and improvisation.

A recipe is a paradoxical construct, a set of directions that specify precision but—baking excepted—anticipate latitude. A recipe is an introduction to the logic of a dish, a scaffold bringing order to the often casual process of making it.

A recipe supplies the bridge between hope and fulfilment, for a recipe offers innumerable opportunities to review, revise, adapt, and improve, to make the dish the cook’s and eater’s own.

She considers the typical recipe template, the spread of international dishes, how particular chefs incorporate stories in their cookbooks, and the role that food plays in celebrations. To illustrate her points, she traces patterns via various go-to recipes: for chicken noodle soup, crepes, green salad, mac and cheese, porridge, and melting-middle chocolate pots.

She considers the typical recipe template, the spread of international dishes, how particular chefs incorporate stories in their cookbooks, and the role that food plays in celebrations. To illustrate her points, she traces patterns via various go-to recipes: for chicken noodle soup, crepes, green salad, mac and cheese, porridge, and melting-middle chocolate pots.

I most enjoyed the sections on comfort food (“a platterful of stability in a turbulent, ever-changing world beset by traumas and tribulations”) and Thanksgiving – coming up on Thursday for Americans. Best piece of trivia: in 1909, President Taft, known for being a big guy, served a 26-pound opossum as well as a 30-pound turkey for the White House holiday dinner. (Who knew possums came that big?!)

Bloom also has a social conscience: in Chapters 5 and 6, she writes about the issues of food insecurity, and child labour in the chocolate production process. As important as these are to draw attention to, it did feel like these sections take away from the main focus of the book. Recipe also feels like it was hurriedly put together – with more typos than I’m used to seeing in a published work. Still, it was an engaging read. [136 pages]

Shameless: A Sexual Reformation by Nadia Bolz-Weber (2019)

“Shame is the lie someone told you about yourself.” ~Anaïs Nin

Bolz-Weber, founding Lutheran pastor of House for All Sinners and Saints in Denver, Colorado, was a mainstay on the speaker programme at Greenbelt Festival in the years I attended. Her main arguments here: people matter more than doctrines, sex (like alcohol, food, work, and anything else that can become the object of addiction) is morally neutral, and Evangelical/Religious Right teachings on sexuality are not biblical.

She believes that purity culture – familiar to any Church kid of my era – did a whole generation a disservice; that teaching young people to view sex as amazing-but-deadly unless you’re a) cis-het and b) married led instead to “a culture of secrecy, hypocrisy, and double standards.”

She believes that purity culture – familiar to any Church kid of my era – did a whole generation a disservice; that teaching young people to view sex as amazing-but-deadly unless you’re a) cis-het and b) married led instead to “a culture of secrecy, hypocrisy, and double standards.”

Purity most often leads to pride or to despair, not to holiness. … Holiness happens when we are integrated as physical, spiritual, sexual, emotional, and political beings.

A number of chapters are built around anecdotes about her parishioners, many of them queer or trans, and about her own life. “The Rocking Chair” is an excellent essay about her experience of pregnancy and parenthood, which includes having an abortion at age 24 before later becoming a mother of two. She knows she would have loved that baby, yet she doesn’t regret her choice at all. She was not ready.

This chapter is followed by an explanation of how abortion became the issue for the political right wing in the USA. Spoiler alert: it had nothing to do with morality; it was all about increasing the voter base. In most Judeo-Christian theology prior to the 1970s, by contrast, it was believed that life started with breath (i.e., at birth, rather than at conception, as the pro-life lobby contends). In other between-chapter asides, she retells the Creation story and proffers an alternative to the Nashville Statement on marriage and gender roles.

Bolz-Weber is a real badass, but it’s not just bravado: she has the scriptures to back it all up. This was a beautiful and freeing book. [198 pages]