Christmas Gift Recommendations for 2017

Something tells me my readers are the sort of people who buy books for their family and friends at the holidays. Consider any rating of 3.5 or above on this blog a solid recommendation; 3 stars is still a qualified recommendation, and by my comments you should be able to tell whether the book would be right for you or a friend. I’ll make another plug for the books I’ve already mentioned here as gift ideas and highlight other books I think would be ideal for the right reader. I read all these books this year, and most were released in 2017, but I have a few backlist titles, too – in those cases I’ve specified the publication year. Since I recommend fiction all the time through my reviews, I’ve given significantly more space to nonfiction.

General suggestions:

For the Shiny New Books Christmas special I chose two books I could see myself giving to lots of people. One was A Glorious Freedom: Older Women Leading Extraordinary Lives by Lisa Congdon, my overall top gift idea. It’s a celebration of women’s attainments after age 40, especially second careers and late-life changes of course. There’s a lively mixture of interviews, first-person essays, inspirational quotes, and profiles of figures like Vera Wang, Laura Ingalls Wilder and Grandma Moses, with Congdon’s whimsical drawings dotted all through. This would make a perfect gift for any woman who’s feeling her age, even if that’s younger than 40. (An essay on gray hair particularly hit home for me.) It’s a reminder that great things can be achieved at any age, and that with the right attitude, we will only grow in confidence and courage over the years. (See my full Nudge review.)

For the Shiny New Books Christmas special I chose two books I could see myself giving to lots of people. One was A Glorious Freedom: Older Women Leading Extraordinary Lives by Lisa Congdon, my overall top gift idea. It’s a celebration of women’s attainments after age 40, especially second careers and late-life changes of course. There’s a lively mixture of interviews, first-person essays, inspirational quotes, and profiles of figures like Vera Wang, Laura Ingalls Wilder and Grandma Moses, with Congdon’s whimsical drawings dotted all through. This would make a perfect gift for any woman who’s feeling her age, even if that’s younger than 40. (An essay on gray hair particularly hit home for me.) It’s a reminder that great things can be achieved at any age, and that with the right attitude, we will only grow in confidence and courage over the years. (See my full Nudge review.)

One Year Wiser: An Illustrated Guide to Mindfulness by Mike Medaglia

One Year Wiser: An Illustrated Guide to Mindfulness by Mike Medaglia

Drawn like an adult coloring book, this mindfulness guide is divided into color-block sections according to the seasons and tackles themes like happiness, gratitude, fighting anxiety and developing a healthy thought life. The layout is varied and unexpected, with abstract ideas represented by bodies in everyday situations. It’s a fresh delivery of familiar concepts.

My thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

An Almost Perfect Christmas by Nina Stibbe

With its short chapters and stocking stuffer dimensions, this is a perfect book to dip into over the holidays. The autobiographical pieces involve Stibbe begrudgingly coming round to things she’s resisted, from Slade’s “Merry Xmas Everybody” to a flaming Christmas pudding. The four short stories, whether nostalgic or macabre, share a wicked sense of humor. You’ll also find an acerbic shopping guide and – best of all – a tongue-in-cheek Christmas A-to-Z. Nearly as funny as Love, Nina. (I reviewed this for the Nov. 29th Stylist “Book Wars” column.)

With its short chapters and stocking stuffer dimensions, this is a perfect book to dip into over the holidays. The autobiographical pieces involve Stibbe begrudgingly coming round to things she’s resisted, from Slade’s “Merry Xmas Everybody” to a flaming Christmas pudding. The four short stories, whether nostalgic or macabre, share a wicked sense of humor. You’ll also find an acerbic shopping guide and – best of all – a tongue-in-cheek Christmas A-to-Z. Nearly as funny as Love, Nina. (I reviewed this for the Nov. 29th Stylist “Book Wars” column.)

For some reason book- and nature-themed books seem to particularly lend themselves to gifting. Do you find that too?

For the fellow book and word lovers in your life:

The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell

The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell

It’s a pleasure to spend a vicarious year running The Book Shop in Wigtown, Scotland with the curmudgeonly Bythell. I enjoyed the nitty-gritty details about acquiring and pricing books, and the unfailingly quirky customer encounters. This would make a great one-year bedside book. (See my full review.)

The Cabinet of Linguistic Curiosities: A Yearbook of Forgotten Words by Paul Anthony Jones

Another perfect bedside book: this is composed of daily one-page entries that link etymology with events from history. I’ve been reading it a page a day since mid-October. A favorite word so far: “vandemonianism” (rowdy, unmannerly behavior), named after the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), first sighted by Europeans on 24 November 1642.

Another perfect bedside book: this is composed of daily one-page entries that link etymology with events from history. I’ve been reading it a page a day since mid-October. A favorite word so far: “vandemonianism” (rowdy, unmannerly behavior), named after the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), first sighted by Europeans on 24 November 1642.

“The Gifts of Reading” by Robert Macfarlane (2016)

This was my other Christmas recommendation for Shiny New Books. A love of literature shared with friends and the books he now gifts to students and a new generation of nature writers are the main themes of this perfect essay. First printed as a stand-alone pamphlet in aid of the Migrant Offshore Aid Station, this is just right for slipping in a stocking.

This was my other Christmas recommendation for Shiny New Books. A love of literature shared with friends and the books he now gifts to students and a new generation of nature writers are the main themes of this perfect essay. First printed as a stand-alone pamphlet in aid of the Migrant Offshore Aid Station, this is just right for slipping in a stocking.

A Girl Walks into a Book: What the Brontës Taught Me about Life, Love, and Women’s Work by Miranda K. Pennington

This charming bibliomemoir reflects on Pennington’s two-decade love affair with the work of the Brontë sisters, especially Charlotte. It cleverly gives side-by-side chronological tours through the Brontës’ biographies and careers and her own life, drawing parallels and noting where she might have been better off if she’d followed in Brontë heroines’ footsteps.

This charming bibliomemoir reflects on Pennington’s two-decade love affair with the work of the Brontë sisters, especially Charlotte. It cleverly gives side-by-side chronological tours through the Brontës’ biographies and careers and her own life, drawing parallels and noting where she might have been better off if she’d followed in Brontë heroines’ footsteps.

For the nature enthusiasts in your life:

A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There by Aldo Leopold

A Sand County Almanac and Sketches Here and There by Aldo Leopold

Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was first published in 1949, but it still rings true. A month-by-month account of life in Wisconsin gives way to pieces set everywhere from Mexico to Manitoba. Beautiful, incisive prose; wonderful illustrations by Charles W. Schwartz.

The History of Bees by Maja Lunde

Blending historical, contemporary and future story lines, this inventive novel, originally published in Norway in 2015, is a hymn to the dying art of beekeeping and a wake-up call about the environmental disaster the disappearance of bees signals. The plot strands share the themes of troubled parenthood and the drive to fulfill one’s purpose. Like David Mitchell, Lunde juggles her divergent time periods and voices admirably. It’s also a beautifully produced book, with an embossed bee on the dust jacket and a black and gold honeycomb pattern across the spine and boards. (See my full Bookbag review.)

Blending historical, contemporary and future story lines, this inventive novel, originally published in Norway in 2015, is a hymn to the dying art of beekeeping and a wake-up call about the environmental disaster the disappearance of bees signals. The plot strands share the themes of troubled parenthood and the drive to fulfill one’s purpose. Like David Mitchell, Lunde juggles her divergent time periods and voices admirably. It’s also a beautifully produced book, with an embossed bee on the dust jacket and a black and gold honeycomb pattern across the spine and boards. (See my full Bookbag review.)

Epitaph for a Peach: Four Seasons on My Family Farm by David Mas Masumoto (1995)

Epitaph for a Peach: Four Seasons on My Family Farm by David Mas Masumoto (1995)

Masumoto is a third-generation Japanese-American peach and grape farmer in California. He takes readers on a quiet journey through the typical events of the farming calendar. It’s a lovely, meditative book about the challenges and joys of this way of life. I would highly recommend it to readers of Wendell Berry.

A Wood of One’s Own by Ruth Pavey

This pleasantly meandering memoir, an account of two decades spent restoring land to orchard in Somerset, will appeal to readers of modern nature writers. Local history weaves through this story, too: everything from the English Civil War to Cecil Sharp’s collecting of folk songs. Bonus: Pavey’s lovely black-and-white line drawings. (See my full review.)

This pleasantly meandering memoir, an account of two decades spent restoring land to orchard in Somerset, will appeal to readers of modern nature writers. Local history weaves through this story, too: everything from the English Civil War to Cecil Sharp’s collecting of folk songs. Bonus: Pavey’s lovely black-and-white line drawings. (See my full review.)

It’s not just books…

There are terrific ideas for other book-related gifts at Sarah’s Book Shelves and Parchment Girl.

With this year’s Christmas money from my mother I bought the five-disc back catalogue of albums from The Bookshop Band. I crowdfunded their nine-disc, 100+-track recording project last year; it was money extremely well spent. So much quality music, and all the songs are based on books. I listen to these albums all the time while I’m working. I look forward to catching up on older songs I don’t know. Check out their Bandcamp site and see if there’s a physical or digital album you’d like to own or give to a fellow book and music lover. They played two commissioned songs at the launch event for The Book of Dust: La Belle Sauvage, so if you’re a Philip Pullman fan you might start by downloading those.

With this year’s Christmas money from my mother I bought the five-disc back catalogue of albums from The Bookshop Band. I crowdfunded their nine-disc, 100+-track recording project last year; it was money extremely well spent. So much quality music, and all the songs are based on books. I listen to these albums all the time while I’m working. I look forward to catching up on older songs I don’t know. Check out their Bandcamp site and see if there’s a physical or digital album you’d like to own or give to a fellow book and music lover. They played two commissioned songs at the launch event for The Book of Dust: La Belle Sauvage, so if you’re a Philip Pullman fan you might start by downloading those.

Would you like to give – or get – any of my recommendations for Christmas?

Nonfiction Novellas for November

Nonfiction novellas – that’s a thing, right? Lots of bloggers are doing Nonfiction November, but I feel like I pick up enough nonfiction naturally (at least 40% of my reading, I’d estimate) that I don’t need a special challenge related to it. I’ve read seven nonfiction works this month that aren’t much longer than 100 pages, or sometimes significantly shorter. For the most part these are nature books and memoirs. I’m finishing off a few more fiction novellas and will post a roundup of mini reviews before the end of the month, along with a list of the titles that didn’t take and some general thoughts on novellas.

“We Should All Be Feminists” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

[48 pages]

This isn’t even a novella, but an essay published in pamphlet form, based on a TED talk Adichie gave as part of a conference on Africa. I appreciate and agree with everything she has to say, yet didn’t find it particularly groundbreaking. Her discussion of the various stereotypes associated with feminists and macho males is more applicable to a society like Lagos, though of course the pay gap and negative connotations placed on women managers are as relevant in the West.

This isn’t even a novella, but an essay published in pamphlet form, based on a TED talk Adichie gave as part of a conference on Africa. I appreciate and agree with everything she has to say, yet didn’t find it particularly groundbreaking. Her discussion of the various stereotypes associated with feminists and macho males is more applicable to a society like Lagos, though of course the pay gap and negative connotations placed on women managers are as relevant in the West.

Favorite line: “At some point I was a Happy African Feminist Who Does Not Hate Men And Who Likes To Wear Lip Gloss And High Heels For Herself And Not For Men.”

Orison for a Curlew: In search of a bird on the edge of extinction by Horatio Clare

[101 pages]

Clare was commissioned to tell the story of the slender-billed curlew, a critically endangered marsh-dwelling bird that might be holding out in places like Siberia and Syria but is largely inaccessible to the European birding community. With little hope of finding a bird as good as extinct, he set out instead to speak to those in Greece, Romania and Bulgaria who had last seen the bird before its disappearance: conservationists, hunters, bird watchers and photographers. Clare writes well about nostalgia, hope and the difference individuals can make, but there’s no getting around the fact that this book doesn’t really do what it promises to. [Also, much as I hate to say it, this is atrociously edited. I know Little Toller is a small operation, but there are some shocking typos in here: “pilgrimmage,” “bridwatching,” “govenor,” “refinerey”; even the name of the author’s town, “Hebdon Bridge”!]

Clare was commissioned to tell the story of the slender-billed curlew, a critically endangered marsh-dwelling bird that might be holding out in places like Siberia and Syria but is largely inaccessible to the European birding community. With little hope of finding a bird as good as extinct, he set out instead to speak to those in Greece, Romania and Bulgaria who had last seen the bird before its disappearance: conservationists, hunters, bird watchers and photographers. Clare writes well about nostalgia, hope and the difference individuals can make, but there’s no getting around the fact that this book doesn’t really do what it promises to. [Also, much as I hate to say it, this is atrociously edited. I know Little Toller is a small operation, but there are some shocking typos in here: “pilgrimmage,” “bridwatching,” “govenor,” “refinerey”; even the name of the author’s town, “Hebdon Bridge”!]

Some favorite lines:

“A huge cloud of black storks jump up like an ambush of Hussars in their red bills and leggings, white fronts and dark uniforms.”

“The wheels click-beat the rails as we follow a river valley north past dozy dolomitic scenery in ageing lemon sunlight”

Herbaceous by Paul Evans

[106 pages]

This was Evans’s first book, and the first issued in the Little Toller monograph series. These are generally exceptionally produced nature books on niche subjects. Herbaceous is hard to categorize. In some ways it’s similar to Evans’s Guardian Country Diary columns: short pieces blending straightforward observations with poetic musings. However, some of them read more like short stories, and the language – appropriately for a book about flora? – can be florid. They probably work better read aloud as poems: I remember him reading “Skunk cabbage” at the New Networks for Nature conference some years back, for instance. Some lines are a little oversaturated with metaphor. But others are truly lovely.

This was Evans’s first book, and the first issued in the Little Toller monograph series. These are generally exceptionally produced nature books on niche subjects. Herbaceous is hard to categorize. In some ways it’s similar to Evans’s Guardian Country Diary columns: short pieces blending straightforward observations with poetic musings. However, some of them read more like short stories, and the language – appropriately for a book about flora? – can be florid. They probably work better read aloud as poems: I remember him reading “Skunk cabbage” at the New Networks for Nature conference some years back, for instance. Some lines are a little oversaturated with metaphor. But others are truly lovely.

A few favorite lines:

“The following morning the text of journeys appear[s] on snow: trident marks of pheasant, double slots of fallow deer, dabs of rabbit.”

“Bordello black and scarlet, six-spot burnet moths swing on the nodding idiot scabious flower through a lavender-blue sky and deep, deep under roots, the fossilised fury of the mollusc’s empire heaves.”

“A bed of pansies tilts flat blue faces to the sun like a deaf and dumb funeral.”

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman

[83 pages]

Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own bout with breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. For instance, “Choose Whose Advice to Take” and “Choose to Enjoy Yourself.” This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help edge, and I think most people would appreciate being given a copy. The only element that felt out of place was the five-page knitting pattern for a hat. Though very similar to Cathy Rentzenbrink’s A Manual for Heartache, this is that tiny bit better.

Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own bout with breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. For instance, “Choose Whose Advice to Take” and “Choose to Enjoy Yourself.” This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help edge, and I think most people would appreciate being given a copy. The only element that felt out of place was the five-page knitting pattern for a hat. Though very similar to Cathy Rentzenbrink’s A Manual for Heartache, this is that tiny bit better.

Favorite lines:

“Make a list of what all you have loved in this unfair and beautiful world.”

“When I couldn’t write about characters that didn’t have cancer and worried I might never get past this single experience, my oncologist told me that cancer didn’t have to be my entire novel. It was just a chapter.”

Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

[130 pages]

Though written in 1955 (I read a 50th anniversary edition copy), this still resonates and deserves to be read alongside feminist nonfiction by Virginia Woolf, May Sarton and Madeleine L’Engle. Solitude is essential for women’s creativity, Lindbergh writes, and this little book, written during a beach vacation in Florida, is about striving for balance in a midlife busy with family commitments. Like Joan Anderson, Lindbergh celebrates the pull of the sea and speaks of life, and especially marriage, as a fluid thing that ebbs and flows. Divided into short, meditative chapters named after different types of shells, this is a relatable work about the search for a simple, whole, purposeful life. The afterword from 1975 and her daughter Reeve’s introduction from 2005 testify to how lasting an influence the book has had.

Though written in 1955 (I read a 50th anniversary edition copy), this still resonates and deserves to be read alongside feminist nonfiction by Virginia Woolf, May Sarton and Madeleine L’Engle. Solitude is essential for women’s creativity, Lindbergh writes, and this little book, written during a beach vacation in Florida, is about striving for balance in a midlife busy with family commitments. Like Joan Anderson, Lindbergh celebrates the pull of the sea and speaks of life, and especially marriage, as a fluid thing that ebbs and flows. Divided into short, meditative chapters named after different types of shells, this is a relatable work about the search for a simple, whole, purposeful life. The afterword from 1975 and her daughter Reeve’s introduction from 2005 testify to how lasting an influence the book has had.

Favorite lines:

“Patience, patience, patience, is what the sea teaches. Patience and faith.”

“The most exhausting thing in life, I have discovered, is being insincere.”

“I no longer pull out grey hairs or sweep down cobwebs.”

“It is fear, I think, that makes one cling nostalgically to the last moment or clutch greedily toward the next.”

Before I Say Goodbye by Ruth Picardie

[116 pages]

Ruth Picardie, an English freelance journalist and newspaper editor, was younger than I am now when she died of breast cancer in September 1997. The cancer had moved into her liver, lungs, bones and brain, and she only managed to write 6.5 weekly columns for Observer Life magazine, which her older sister, Justine Picardie, edited. Matt Seaton, Ruth’s widower, and Justine gathered a selection of e-mails exchanged with friends and letters sent by Observer readers and put them together with the columns to make a brief chronological record of Ruth’s final illness, ending with a 20-page epilogue by Seaton. Ruth comes across as down-to-earth and self-deprecating. All the rather Bridget Jones-ish fretting over her weight and complexion perhaps reflects that it felt easier to think about daily practicalities than about the people she was leaving behind. This is a poignant book, for sure, but feels fixed in time, not really reaching into Ruth’s earlier life or assessing her legacy. I’ve moved straight on to Justine’s bereavement memoir, If the Spirit Moves You, and hope it adds more context.

Ruth Picardie, an English freelance journalist and newspaper editor, was younger than I am now when she died of breast cancer in September 1997. The cancer had moved into her liver, lungs, bones and brain, and she only managed to write 6.5 weekly columns for Observer Life magazine, which her older sister, Justine Picardie, edited. Matt Seaton, Ruth’s widower, and Justine gathered a selection of e-mails exchanged with friends and letters sent by Observer readers and put them together with the columns to make a brief chronological record of Ruth’s final illness, ending with a 20-page epilogue by Seaton. Ruth comes across as down-to-earth and self-deprecating. All the rather Bridget Jones-ish fretting over her weight and complexion perhaps reflects that it felt easier to think about daily practicalities than about the people she was leaving behind. This is a poignant book, for sure, but feels fixed in time, not really reaching into Ruth’s earlier life or assessing her legacy. I’ve moved straight on to Justine’s bereavement memoir, If the Spirit Moves You, and hope it adds more context.

Favorite lines:

“You ram a non-organic carrot up the arse of the next person who advises you to start drinking homeopathic frogs’ urine.”

“Worse than the God botherers, though, are the road accident rubber-neckers, who seem to find terminal illness exciting, the secular Samaritans looking for glory.”

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd

[108 pages]

This is something of a lost nature classic that has been championed by Robert Macfarlane (who contributes a 25-page introduction to this Canongate edition). Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing: “the most appalling quality of water is its strength. I love its flash and gleam, its music, its pliancy and grace, its slap against my body; but I fear its strength.” Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude: “Yet often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.”

This is something of a lost nature classic that has been championed by Robert Macfarlane (who contributes a 25-page introduction to this Canongate edition). Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing: “the most appalling quality of water is its strength. I love its flash and gleam, its music, its pliancy and grace, its slap against my body; but I fear its strength.” Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude: “Yet often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination, when I reach nowhere in particular, but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him.”

Have you read any of these novellas? Which one takes your fancy?

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel

I’m delighted to announce that I’ve been invited to be on the official shadow panel for the Sunday Times / Peters Fraser + Dunlop Young Writer of the Year Award, in association with The University of Warwick (to give it its full and proper title). Here’s a bit of background on the prize, from its website:

The prize “is awarded annually to the best work of published or self-published fiction, non-fiction or poetry by a British or Irish author aged between 18 and 35, and has gained attention and acclaim across the publishing industry and press. £5,000 is given to the overall winner and £500 to each of the three runners-up.

“Since it began in 1991, the award has had a striking impact, boasting a stellar list of alumni that have gone on to become leading lights of contemporary literature. The 2016 Award was presented to Max Porter for his extraordinary debut, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. Following a five-year break, the prestigious award returned with a bang in 2015, awarding debut poet Sarah Howe the top prize for her phenomenal first collection, Loop of Jade.”

Past winners include Ross Raisin, Adam Foulds, Naomi Alderman, Robert Macfarlane, William Fiennes, Zadie Smith, Sarah Waters, Francis Spufford, Simon Armitage and Helen Simpson.

This year’s official judging panel is made up of Andrew Holgate, literary editor of the Sunday Times, and writers Lucy Hughes-Hallett and Elif Shafak.

I’m joined on the shadow panel by four other book bloggers, several of whom you will recognize as long-time friends of this blog:

- Dane Cobain (SocialBookshelves)

- Eleanor Franzen (Elle Thinks)

- Annabel Gaskell (Annabookbel)

- Clare Rowland (A Little Blog of Books)

Here are some key upcoming dates:

- Sunday October 29th: shortlist announced in Sunday Times

- November 18th: book bloggers event with readings from the shortlisted authors (Groucho Club, London)

- November 27th: deadline for shadow panel winner decision

- November 29th: shadow panel winner announced on STPFD website

- December 3rd: shadow panel winner announced in Sunday Times

- December 7th: prize-giving ceremony and winner announcement (London Library)

I’m so looking forward to getting stuck into the shortlisted books and discussing them! I’ll be posting a review of each one in November.

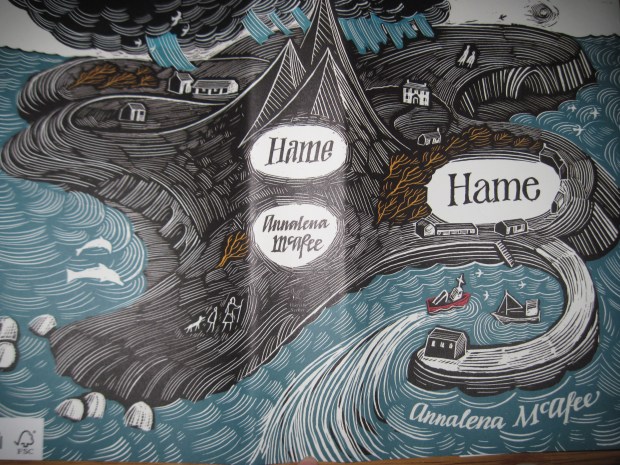

Review & Giveaway: Hame by Annalena McAfee

As I mentioned on Tuesday, I previously knew of Annalena McAfee only as Mrs. Ian McEwan, though she has a distinguished literary background: she founded the Guardian Review and edited it for six years, was Arts and Literary Editor of the Financial Times, and is the author of multiple children’s books and one previous novel for adults, The Spoiler (2011).

As I mentioned on Tuesday, I previously knew of Annalena McAfee only as Mrs. Ian McEwan, though she has a distinguished literary background: she founded the Guardian Review and edited it for six years, was Arts and Literary Editor of the Financial Times, and is the author of multiple children’s books and one previous novel for adults, The Spoiler (2011).

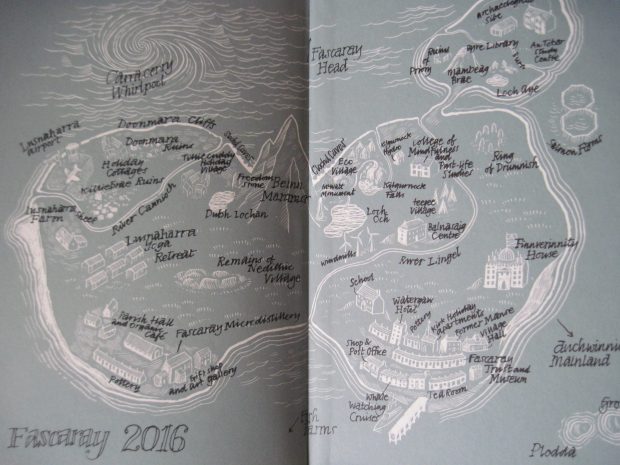

Well, anyone who reads Hame will be saying “Ian who?” as this is on such a grand scale compared to anything McEwan has ever attempted. The subtitle, “The Fascaray Archives,” gives an idea of how thorough McAfee means to be: the life of fictional poet Grigor McWatt is her way into everything that forms the Scottish identity. Her invented island of Fascaray is a carefully constructed microcosm of Scotland from ancient times to today. I loved the little glimpses of recent history, like the referendum on independence and a Donald Trump figure, billionaire “Archie Tupper,” bulldozing an environmentally sensitive area to build his new golf course (this really happened, in Aberdeenshire in 2012).

Narrator Mhairi McPhail arrives on Fascaray in August 2014, her nine-year-old daughter Agnes in tow. She’s here to oversee the opening of a new museum, edit a seven-volume edition of McWatt’s magnum opus, The Fascaray Compendium (a 70-year journal detailing the island’s history, language, flora, fauna and customs), and complete a critical biography of the poet. Over the next four months she often questions the feasibility of her multi-strand project. She also frets about her split from Marco, whom she left back in New York City after their separate infidelities. And her rootlessness – she’s Canadian via Scotland but has spent a lot of time in the States, giving her a mixed-up heritage and accent – is a constant niggle.

Mhairi’s narrative sections share space with excerpts from her biography of McWatt and extracts from McWatt’s own writing: The Fascaray Compendium, newspaper columns, letters to on-again, off-again lover Lilias Hogg, and Scots translations of famous poets from Blake to Yeats. We learn of key events from the island’s history through Mhairi’s biography and McWatt’s prose, including ongoing tension between lairds and crofters, Finnverinnity House being used as a Special Ops training school during World War II, a lifeboat lost in a gale in the 1970s, and the way the fishing industry is now ceding to hydroelectric power.

The balance between the alternating elements isn’t quite right – sections from Mhairi’s contemporary diary seem to get shorter as the novel goes along, such that it feels like there’s not enough narrative to anchor the book. Faced with yet more Scots poetry and vocabulary lists, or passages from Mhairi’s dry biography, it’s mighty tempting to skim.

That’s a shame, as the novel contains some truly lovely writing, particularly in McWatt’s nature observations:

In July and August, on rare days of startling and sustained heat, dragonflies as blue as the cloudless skies shimmer over cushions of moss by the burn while the midges, who abhor direct sunlight, are nowhere to be seen. Out to sea, somnolent groups of whales pass like cortèges of cruise ships and around them dolphins and porpoises joyously arc and dip as if stitching the ocean’s silken canopy of turquoise, gentian and cobalt.

For centuries male Fascaradians have sailed in the autumn, at the time of the ripe barley and the fruiting buckthorn, to hunt the plump young solan geese or gannets – the guga – near their nesting sites on the uninhabited rock pinnacles of Plodda and Grodda. No true Fascaradian can suffer vertigo since the scaling of these granite towers is done without the aid of mountaineers’ crampons or picks.

“Hame” means home in Scots – like in McWatt’s claim to fame, the folk-pop song “Hame tae Fascaray” – and themes of home and identity are strong here. The novel asks to what extent identity is bound up with a particular country and language, and whether we can craft our own selves. Must the place you come from always be the same as the home you choose? I could relate to Mhairi’s feeling that there’s nowhere she belongs, whether she’s in the bustle of New York or “marooned on a patch of damp peat floating in the North Sea.”

A map of the island from the inside of the back cover.

Although the blend of elements initially made me think that this would resemble A.S. Byatt’s Possession, it’s actually more like Rachel Cantor’s Good on Paper, which similarly stars a scholar who’s a single parent to a precocious daughter. In places I was also reminded of the work of Scarlett Thomas, Sara Maitland and Sarah Moss, and there’s even an echo of Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks in the inventories of dialect words.

If you’ve done much traveling in Scotland, an added pleasure of the novel is trying to spot places you’ve been. (I thought I could see traces of Stromness, Orkney; indeed, McWatt reminded me most of Orcadian poet George Mackay Brown.) The comprehensive, archival approach didn’t completely win me over, but I was impressed by the book’s scope and its affectionate portrait of a beloved country. McAfee is of Scots-Irish parentage herself, and you can tell this is a true labor of love, and a cogent tribute.

Hame was published by Harvill Secker on February 9th. With thanks to Anna Redman for sending a free copy for review.

My rating:

Giveaway Announcement!

I was accidentally sent two copies of Hame, so I am giving one away to a reader. Alas, this giveaway will have to be UK-only – the book is a hardback of nearly 600 pages, so would be prohibitively expensive to send abroad.

If you’re interested in winning a copy, simply leave a comment to that effect below. The competition will be open through the end of Friday the 17th and I will choose a winner at random on Saturday the 18th, to be announced via the comments and a personal e-mail.

Good luck!

What I’ve Been Reading Recently

My own paper books! Really! Not exclusively; I still find Kindle books easiest to read during lunches and on the cross trainer. Still, I’m pleased with the progress I’ve made towards my summer resolution of reading my own books. In August I’ll have to get to grips with some of those doorstoppers I’ve been meaning to pick up. Below I give brief write-ups of what I’ve gotten through lately and recall how these books came into my collection to start with.

June by Gerbrand Bakker: It seemed to make sense to read this during the month of June. I loved Bakker’s The Twin, but struggled to connect with this one. The first chapter and the last three (starting with “June”) are the best – I felt that the core 1969 material about the Queen’s visit and the family’s tragedy would make for a great short story or novella, but the bulk of the novel is languid contemporary moping about the ongoing effects on the Kaans. It took me forever to figure out who all the characters were and keep them straight (brothers Jan and Johan, for instance), and the way the perspective drifts from one to another doesn’t help with that. Matriarch Anna, with her habit of going up and lying in the hayloft when life gets to be too much for her, was my favorite character.

June by Gerbrand Bakker: It seemed to make sense to read this during the month of June. I loved Bakker’s The Twin, but struggled to connect with this one. The first chapter and the last three (starting with “June”) are the best – I felt that the core 1969 material about the Queen’s visit and the family’s tragedy would make for a great short story or novella, but the bulk of the novel is languid contemporary moping about the ongoing effects on the Kaans. It took me forever to figure out who all the characters were and keep them straight (brothers Jan and Johan, for instance), and the way the perspective drifts from one to another doesn’t help with that. Matriarch Anna, with her habit of going up and lying in the hayloft when life gets to be too much for her, was my favorite character.

[Bought in a local charity shop for 20 pence.]

Uncommon Ground by Dominick Tyler: This is like a photographic companion to Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks. Journeying around Britain, Tyler illustrates different geographical features, many of them known by archaic or folksy names. Some are just record shots, while others are true works of art. I especially liked the more whimsical terms: “Monkey’s birthday” for simultaneous rain and sunshine, and “Witches’ knickers” for plastic scraps waving from a tree or fence.

Uncommon Ground by Dominick Tyler: This is like a photographic companion to Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks. Journeying around Britain, Tyler illustrates different geographical features, many of them known by archaic or folksy names. Some are just record shots, while others are true works of art. I especially liked the more whimsical terms: “Monkey’s birthday” for simultaneous rain and sunshine, and “Witches’ knickers” for plastic scraps waving from a tree or fence.

[I won a copy in a Guardian giveaway.]

Wave by Sonali Deraniyagala: The author was vacationing with her family at a national park on the southeast coast of her native Sri Lanka in December 2004 when the Boxing Day tsunami hit, killing her parents, husband, and two sons. Job-like, Deraniyagala gives shape to her grief and lovingly remembers a family life now gone forever as she tours her childhood home in Colombo and her London house. It’s not until over six years later that she feels “I can rest … with the impossible truth of my loss, which I have to compress often and misshape, just so I can bear it—so I can cook or teach or floss my teeth.” This is a wonderful tribute to everyone she lost. Her husband and sons, especially, come through clearly as individuals you feel that you know. Although it’s not a focus of the memoir, Sri Lanka’s natural beauty and food culture struck me – this would be an appealing place to visit.

Wave by Sonali Deraniyagala: The author was vacationing with her family at a national park on the southeast coast of her native Sri Lanka in December 2004 when the Boxing Day tsunami hit, killing her parents, husband, and two sons. Job-like, Deraniyagala gives shape to her grief and lovingly remembers a family life now gone forever as she tours her childhood home in Colombo and her London house. It’s not until over six years later that she feels “I can rest … with the impossible truth of my loss, which I have to compress often and misshape, just so I can bear it—so I can cook or teach or floss my teeth.” This is a wonderful tribute to everyone she lost. Her husband and sons, especially, come through clearly as individuals you feel that you know. Although it’s not a focus of the memoir, Sri Lanka’s natural beauty and food culture struck me – this would be an appealing place to visit.

[Borrowed from a friend in America.]

Out of Sheer Rage by Geoff Dyer: This is a book about D.H. Lawrence in the same way that Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation is a film of The Orchid Thief. In other words, it’s not particularly about Lawrence at all; it’s just as much, if not more, about Geoff Dyer – his laziness, his procrastination, his curmudgeonly attitude, his futile search for the perfect places to read Lawrence’s works and write about Lawrence, his failure to feel the proper reverence at Lawrence sites, and so on. While I can certainly sympathize with Dyer’s wry comments about his work habits (“I hate doing anything in life that requires an effort”; “better reading than writing”; “all things in which I am interested … [are] a source of stress and anxiety”), I liked best the parts of the book where he actually writes about Lawrence. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

Out of Sheer Rage by Geoff Dyer: This is a book about D.H. Lawrence in the same way that Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation is a film of The Orchid Thief. In other words, it’s not particularly about Lawrence at all; it’s just as much, if not more, about Geoff Dyer – his laziness, his procrastination, his curmudgeonly attitude, his futile search for the perfect places to read Lawrence’s works and write about Lawrence, his failure to feel the proper reverence at Lawrence sites, and so on. While I can certainly sympathize with Dyer’s wry comments about his work habits (“I hate doing anything in life that requires an effort”; “better reading than writing”; “all things in which I am interested … [are] a source of stress and anxiety”), I liked best the parts of the book where he actually writes about Lawrence. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

[Bought – I think in the Hay Cinema Bookshop – for £2.99.]

The Middlesteins by Jami Attenberg: I was surprised how much I loved this. On the face of it it’s a fairly conventional dysfunctional family novel à la Jonathan Franzen, set among a Jewish family in Chicago. The main drama is provided by the mother, Edie, who seems to be slowly eating herself to death: she gorges herself on snacks and fast food several times a day even though she’s facing a third major surgery for diabetes. Her husband, Richard, ditched her in her time of need, leaving their adult children to pick up the slack. Every character is fully rounded (pun intended?) and the family interactions feel perfectly true to life. This isn’t really an ‘issues’ book, yet it deals with obesity in a much more subtle and compassionate way than Lionel Shriver’s Big Brother. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

The Middlesteins by Jami Attenberg: I was surprised how much I loved this. On the face of it it’s a fairly conventional dysfunctional family novel à la Jonathan Franzen, set among a Jewish family in Chicago. The main drama is provided by the mother, Edie, who seems to be slowly eating herself to death: she gorges herself on snacks and fast food several times a day even though she’s facing a third major surgery for diabetes. Her husband, Richard, ditched her in her time of need, leaving their adult children to pick up the slack. Every character is fully rounded (pun intended?) and the family interactions feel perfectly true to life. This isn’t really an ‘issues’ book, yet it deals with obesity in a much more subtle and compassionate way than Lionel Shriver’s Big Brother. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

[In last year’s Christmas stocking, from the Waynesboro, Pennsylvania Dollar Tree.]

The Republic of Love by Carol Shields: Not one of my favorites from Shields, but still enjoyable and reminiscent of Anne Tyler’s The Accidental Tourist. Her chapters alternate between the perspectives of radio disc jockey Tom Avery and folklorist Fay McLeod, two Winnipeg lonely hearts who each have their share of broken relationships behind them. It’s clear they’re going to meet and fall in love, but Shields is careful to interrogate myths of love at first sight and happily ever after. I especially liked the surprising interconnectedness of everyone in Winnipeg, the subplot about Fay’s parents’ marriage, and the habit of recording minor characters’ monologues. My major points of criticism would be that Tom sometimes feels like a caricature and I wasn’t entirely sure what the mermaid material was meant to achieve. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

The Republic of Love by Carol Shields: Not one of my favorites from Shields, but still enjoyable and reminiscent of Anne Tyler’s The Accidental Tourist. Her chapters alternate between the perspectives of radio disc jockey Tom Avery and folklorist Fay McLeod, two Winnipeg lonely hearts who each have their share of broken relationships behind them. It’s clear they’re going to meet and fall in love, but Shields is careful to interrogate myths of love at first sight and happily ever after. I especially liked the surprising interconnectedness of everyone in Winnipeg, the subplot about Fay’s parents’ marriage, and the habit of recording minor characters’ monologues. My major points of criticism would be that Tom sometimes feels like a caricature and I wasn’t entirely sure what the mermaid material was meant to achieve. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

[In poor condition, so free from the Oxfam bookshop where I volunteered in Romsey in 2007–8.]

Not That Kind of Girl: A Memoir by Carlene Bauer: Lena Dunham forever rendered this memoir obscure by stealing the title. I read it because I adored Bauer’s debut novel, Frances and Bernard. This could accurately be described as a spiritual memoir, and I think will probably appeal most to readers who grew up in a restrictive religious setting. A bookish, introspective adolescent, Bauer was troubled by how her church and Christian school denied the validity of secular art, including the indie rock she loved and the literature she lost herself in. All the same, Christian notions of purity and purpose stuck with her throughout her college days in Baltimore and then when she was trying to make it in publishing in New York City. This book resonated with my experience in many ways. What Bauer does best is to capture a fleeting mindset and its evolution into a broader way of thinking. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

Not That Kind of Girl: A Memoir by Carlene Bauer: Lena Dunham forever rendered this memoir obscure by stealing the title. I read it because I adored Bauer’s debut novel, Frances and Bernard. This could accurately be described as a spiritual memoir, and I think will probably appeal most to readers who grew up in a restrictive religious setting. A bookish, introspective adolescent, Bauer was troubled by how her church and Christian school denied the validity of secular art, including the indie rock she loved and the literature she lost herself in. All the same, Christian notions of purity and purpose stuck with her throughout her college days in Baltimore and then when she was trying to make it in publishing in New York City. This book resonated with my experience in many ways. What Bauer does best is to capture a fleeting mindset and its evolution into a broader way of thinking. (Expanded review on Goodreads.)

[Bought cheap on Amazon USA to qualify for super saver shipping.]

A statue of Alexander von Humboldt, in the grand stairwell of the Natural History Museum in Vienna.

Measuring the World by Daniel Kehlmann: “Whenever things were frightening, it was a good idea to measure them.” This is a delightful historical picaresque about two late-eighteenth-century German scientists: Alexander von Humboldt, who valiantly explored South America and the Russian steppes, and Carl Friedrich Gauss, a misanthropic mathematician whose true genius wasn’t fully realized in his surveying and astronomical work. Both difficult in their own way, the men represent different models for how to do science: an adventurous one who goes on journeys of discovery, and one who stays at home looking at what’s right under his nose. I especially loved Gauss’s hot-air balloon ride and Humboldt’s attempt to summit a mountain. The lack of speech marks somehow adds to the dry wit.

[Purchased via a donation to the Book-Cycle of Exeter.]

What have you been reading recently?

My Favorite Nonfiction Reads of 2015

Without further ado, I present to you my 15 favorite non-fiction books read in 2015. I’m a memoir junkie so many of these fit under that broad heading, but I’ve dipped into other areas too. I give two favorites for each category, then count down my top 7 memoirs read this year.

Note: Only four of these were actually published in 2015; for the rest I’ve given the publication year. Many of them I’ve already previewed through the year, so – like I did yesterday for fiction – I’m limiting myself to two sentences per title: the first is a potted summary; the second tells you why you should read this book. (Links given to full reviews.)

Foodie Lit

A Homemade Life: Stories and Recipes from My Kitchen Table by Molly Wizenberg (2009): Wizenberg reflects on the death of her father Burg from cancer, time spent living in Paris, building a new life in Seattle, starting her food blog, and meeting her husband through it. Each brief autobiographical essay is perfectly formed and followed by a relevant recipe, capturing precisely how food is tied up with memories.

A Homemade Life: Stories and Recipes from My Kitchen Table by Molly Wizenberg (2009): Wizenberg reflects on the death of her father Burg from cancer, time spent living in Paris, building a new life in Seattle, starting her food blog, and meeting her husband through it. Each brief autobiographical essay is perfectly formed and followed by a relevant recipe, capturing precisely how food is tied up with memories.

Comfort Me with Apples: More Adventures at the Table by Ruth Reichl (2001): Reichl traces the rise of American foodie culture in the 1970s–80s (Alice Waters and Wolfgang Puck) through her time as a food critic for the Los Angeles Times, also weaving in personal history – from a Berkeley co-op with her first husband to a home in the California hills with her second after affairs and a sticky divorce. Throughout she describes meals in mouth-watering detail, like this Thai dish: “The hot-pink soup was dotted with lacy green leaves of cilantro, like little bursts of breeze behind the heat. … I took another spoonful of soup and tasted citrus, as if lemons had once gone gliding through and left their ghosts behind.”

Comfort Me with Apples: More Adventures at the Table by Ruth Reichl (2001): Reichl traces the rise of American foodie culture in the 1970s–80s (Alice Waters and Wolfgang Puck) through her time as a food critic for the Los Angeles Times, also weaving in personal history – from a Berkeley co-op with her first husband to a home in the California hills with her second after affairs and a sticky divorce. Throughout she describes meals in mouth-watering detail, like this Thai dish: “The hot-pink soup was dotted with lacy green leaves of cilantro, like little bursts of breeze behind the heat. … I took another spoonful of soup and tasted citrus, as if lemons had once gone gliding through and left their ghosts behind.”

Nature Books

Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field by John Lewis-Stempel (2014): Lewis-Stempel is a proper third-generation Herefordshire farmer, but also a naturalist with a poet’s eye. Magical moments and lovely prose, as in “The dew, trapped in the webs of countless money spiders, has skeined the entire field in tiny silken pocket squares, gnomes’ handkerchiefs dropped in the sward.”

Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field by John Lewis-Stempel (2014): Lewis-Stempel is a proper third-generation Herefordshire farmer, but also a naturalist with a poet’s eye. Magical moments and lovely prose, as in “The dew, trapped in the webs of countless money spiders, has skeined the entire field in tiny silken pocket squares, gnomes’ handkerchiefs dropped in the sward.”

Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane: This new classic of nature writing zeroes in on the language we use to talk about our environment, both individual words – which Macfarlane celebrates in nine mini-glossaries alternating with the prose chapters – and the narratives we build around places, via discussions of the work of nature writers he admires. Whether poetic (“heavengravel,” Gerard Manley Hopkins’s term for hailstones), local and folksy (“wonty-tump,” a Herefordshire word for a molehill), or onomatopoeic (on Exmoor, “zwer” is the sound of partridges taking off), his vocabulary words are a treasure trove.

Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane: This new classic of nature writing zeroes in on the language we use to talk about our environment, both individual words – which Macfarlane celebrates in nine mini-glossaries alternating with the prose chapters – and the narratives we build around places, via discussions of the work of nature writers he admires. Whether poetic (“heavengravel,” Gerard Manley Hopkins’s term for hailstones), local and folksy (“wonty-tump,” a Herefordshire word for a molehill), or onomatopoeic (on Exmoor, “zwer” is the sound of partridges taking off), his vocabulary words are a treasure trove.

Theology Books

Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith by Kathleen Norris (1998): In few-page essays, Norris gives theological words and phrases a rich, jargon-free backstory through anecdote, scripture and lived philosophy. This makes the shortlist of books I would hand to skeptics to show them there might be something to this Christianity nonsense after all.

Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith by Kathleen Norris (1998): In few-page essays, Norris gives theological words and phrases a rich, jargon-free backstory through anecdote, scripture and lived philosophy. This makes the shortlist of books I would hand to skeptics to show them there might be something to this Christianity nonsense after all.

My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer by Christian Wiman (2013): Seven years into a cancer journey, Wiman, a poet, gives an intimate picture of faith and doubt as he has lived with them in the shadow of death. Nearly every page has a passage that cuts right to the quick of what it means to be human and in interaction with other people and the divine.

My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer by Christian Wiman (2013): Seven years into a cancer journey, Wiman, a poet, gives an intimate picture of faith and doubt as he has lived with them in the shadow of death. Nearly every page has a passage that cuts right to the quick of what it means to be human and in interaction with other people and the divine.

General Nonfiction

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life by Hermione Lee (2013): Although Penelope Fitzgerald always guarded literary ambitions, she was not able to pursue her writing wholeheartedly until she had reared three children and nursed her hapless husband through his last illness. This is a thorough and sympathetic appreciation of an underrated author, and another marvellously detailed biography from Lee.

Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life by Hermione Lee (2013): Although Penelope Fitzgerald always guarded literary ambitions, she was not able to pursue her writing wholeheartedly until she had reared three children and nursed her hapless husband through his last illness. This is a thorough and sympathetic appreciation of an underrated author, and another marvellously detailed biography from Lee.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande (2014): A surgeon’s essential guide to decision-making about end-of-life care, but also a more philosophical treatment of the question of what makes life worth living: When should we extend life, and when should we concentrate more on the quality of our remaining days than their quantity? The title condition applies to all, so this is a book everyone should read.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande (2014): A surgeon’s essential guide to decision-making about end-of-life care, but also a more philosophical treatment of the question of what makes life worth living: When should we extend life, and when should we concentrate more on the quality of our remaining days than their quantity? The title condition applies to all, so this is a book everyone should read.

Memoirs

The Year My Mother Came Back by Alice Eve Cohen: Wry and heartfelt, this is a wonderful memoir about motherhood in all its variations and complexities; the magic realism (Cohen’s dead mother keeps showing up) is an added delight. I recommend this no matter what sort of relationship, past or present, you have with your mother, especially if you’re also a fan of Anne Lamott and Abigail Thomas.

The Year My Mother Came Back by Alice Eve Cohen: Wry and heartfelt, this is a wonderful memoir about motherhood in all its variations and complexities; the magic realism (Cohen’s dead mother keeps showing up) is an added delight. I recommend this no matter what sort of relationship, past or present, you have with your mother, especially if you’re also a fan of Anne Lamott and Abigail Thomas.

- The Art of Memoir

by Mary Karr: There is a wealth of practical advice here, on topics such as choosing the right carnal details (not sexual – or not only sexual – but physicality generally), correcting facts and misconceptions, figuring out a structure, and settling on your voice. Karr has been teaching (and writing) memoirs at Syracuse University for years now, so she’s thought deeply about what makes them work, and sets her theories out clearly for readers at any level of familiarity.

by Mary Karr: There is a wealth of practical advice here, on topics such as choosing the right carnal details (not sexual – or not only sexual – but physicality generally), correcting facts and misconceptions, figuring out a structure, and settling on your voice. Karr has been teaching (and writing) memoirs at Syracuse University for years now, so she’s thought deeply about what makes them work, and sets her theories out clearly for readers at any level of familiarity.

A Circle of Quiet by Madeleine L’Engle (1971): In this account of a summer spent at her family’s Connecticut farmhouse, L’Engle muses on theology, purpose, children’s education, the writing life, the difference between creating stories for children and adults, neighbors and fitting into a community, and much besides. If, like me, you only knew L’Engle through her Wrinkle in Time children’s series, this journal should come as a revelation.

A Circle of Quiet by Madeleine L’Engle (1971): In this account of a summer spent at her family’s Connecticut farmhouse, L’Engle muses on theology, purpose, children’s education, the writing life, the difference between creating stories for children and adults, neighbors and fitting into a community, and much besides. If, like me, you only knew L’Engle through her Wrinkle in Time children’s series, this journal should come as a revelation.

-

Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh (2014): “Terrible job, neurosurgery. Don’t do it.” – luckily for us, Henry Marsh reports back from the frontlines of brain surgery so we don’t have to. In my favorite passages, Marsh reflects on the mind-blowing fact that the few pounds of tissue stored in our heads could be the site of our consciousness, our creativity, our personhood – everything we traditionally count as the soul.

Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh (2014): “Terrible job, neurosurgery. Don’t do it.” – luckily for us, Henry Marsh reports back from the frontlines of brain surgery so we don’t have to. In my favorite passages, Marsh reflects on the mind-blowing fact that the few pounds of tissue stored in our heads could be the site of our consciousness, our creativity, our personhood – everything we traditionally count as the soul.

I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place by Howard Norman (2013): Norman has quickly become one of my favorite writers. You wouldn’t think these disparate autobiographical essays would fit together as a whole, given that they range in subject from Inuit folktales and birdwatching to a murder–suicide committed in Norman’s Washington, D.C. home and a girlfriend’s death in a plane crash, but somehow they do; after all, “A whole world of impudent detours, unbridled perplexities, degrading sorrow, and exacting joys can befall a person in a single season, not to mention a lifetime.”

I Hate to Leave This Beautiful Place by Howard Norman (2013): Norman has quickly become one of my favorite writers. You wouldn’t think these disparate autobiographical essays would fit together as a whole, given that they range in subject from Inuit folktales and birdwatching to a murder–suicide committed in Norman’s Washington, D.C. home and a girlfriend’s death in a plane crash, but somehow they do; after all, “A whole world of impudent detours, unbridled perplexities, degrading sorrow, and exacting joys can befall a person in a single season, not to mention a lifetime.”

Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man by Bill Clegg (2010): Through this book I followed literary agent Bill Clegg on dozens of taxi rides between generic hotel rooms and bar toilets and New York City offices and apartments; together we smoked innumerable crack pipes and guzzled dozens of bottles of vodka while letting partners and family members down and spiraling further down into paranoia and squalor. He achieves a perfect balance between his feelings at the time – being out of control and utterly enslaved to his next hit – and the hindsight that allows him to see what a pathetic figure he was becoming.

Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man by Bill Clegg (2010): Through this book I followed literary agent Bill Clegg on dozens of taxi rides between generic hotel rooms and bar toilets and New York City offices and apartments; together we smoked innumerable crack pipes and guzzled dozens of bottles of vodka while letting partners and family members down and spiraling further down into paranoia and squalor. He achieves a perfect balance between his feelings at the time – being out of control and utterly enslaved to his next hit – and the hindsight that allows him to see what a pathetic figure he was becoming.

And my overall favorite nonfiction book of the year:

1. The Light of the World by Elizabeth Alexander: In short vignettes, beginning afresh with every chapter, Alexander conjures up the life she lived with – and after the sudden death of – her husband Ficre Ghebreyesus, an Eritrean chef and painter. This book is the most wonderful love letter you could imagine, and no less beautiful for its bittersweet nature.

1. The Light of the World by Elizabeth Alexander: In short vignettes, beginning afresh with every chapter, Alexander conjures up the life she lived with – and after the sudden death of – her husband Ficre Ghebreyesus, an Eritrean chef and painter. This book is the most wonderful love letter you could imagine, and no less beautiful for its bittersweet nature.

What were some of your best nonfiction reads of the year?

I’ve been interested in

I’ve been interested in

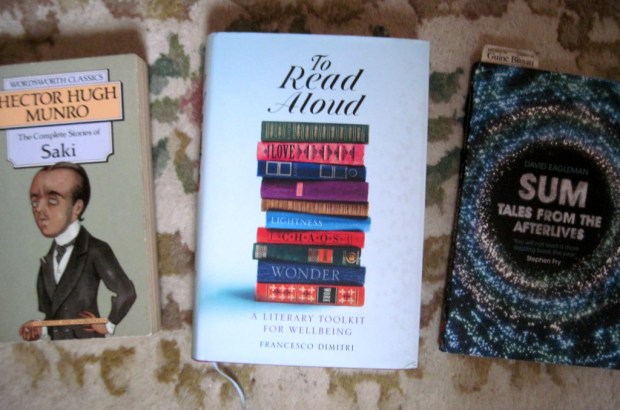

For reading aloud with my husband, Ella prescribed one short story per evening sitting – a way for me to get through short story collections, which I sometimes struggle to finish, and a different way to engage with books. We also talked about the value of rereading childhood favorites such as Watership Down and Little Women, which I haven’t gone back to since I was nine and 12, respectively. In this anniversary year, Little Women would be the ideal book to reread (and the new television adaptation is pretty good too, Ella thinks).

For reading aloud with my husband, Ella prescribed one short story per evening sitting – a way for me to get through short story collections, which I sometimes struggle to finish, and a different way to engage with books. We also talked about the value of rereading childhood favorites such as Watership Down and Little Women, which I haven’t gone back to since I was nine and 12, respectively. In this anniversary year, Little Women would be the ideal book to reread (and the new television adaptation is pretty good too, Ella thinks). Various books came up over the course of our conversation: Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone [appearance in The Novel Cure: The Ten Best Novels to Cure the Xenophobic, but Ella brought it up because of the medical theme], Tom Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume [cure: ageing, horror of], and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, a nonfiction guide to thinking creatively about your life, chiefly through 20-minute automatic writing exercises every morning. We agreed that it’s impossible to dismiss a whole genre, even if I do find myself weary of certain trends, like dystopian fiction (I introduced Ella to Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus, one of my favorite recent examples).

Various books came up over the course of our conversation: Abraham Verghese’s Cutting for Stone [appearance in The Novel Cure: The Ten Best Novels to Cure the Xenophobic, but Ella brought it up because of the medical theme], Tom Robbins’ Jitterbug Perfume [cure: ageing, horror of], and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way, a nonfiction guide to thinking creatively about your life, chiefly through 20-minute automatic writing exercises every morning. We agreed that it’s impossible to dismiss a whole genre, even if I do find myself weary of certain trends, like dystopian fiction (I introduced Ella to Claire Vaye Watkins’ Gold Fame Citrus, one of my favorite recent examples). I came away with two instant prescriptions: Heligoland by Shena Mackay [cure: moving house], about a shell-shaped island house that used to be the headquarters of a cult. It’s a perfect short book, Ella tells me, and will help dose my feelings of rootlessness after moving more than 10 times in the last 10 years. She also prescribed Family Matters by Rohinton Mistry [cure: ageing parents] and an eventual reread of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections. As we discussed various other issues, such as my uncertainty about having children, Ella said she could think of 20 or more books to recommend me. “That’s a good thing, right?!” I asked.

I came away with two instant prescriptions: Heligoland by Shena Mackay [cure: moving house], about a shell-shaped island house that used to be the headquarters of a cult. It’s a perfect short book, Ella tells me, and will help dose my feelings of rootlessness after moving more than 10 times in the last 10 years. She also prescribed Family Matters by Rohinton Mistry [cure: ageing parents] and an eventual reread of Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections. As we discussed various other issues, such as my uncertainty about having children, Ella said she could think of 20 or more books to recommend me. “That’s a good thing, right?!” I asked.

As soon as I got back from London I ordered secondhand copies of Heligoland, Jitterbug Perfume and The Artist’s Way, and borrowed Family Matters from the public library the next day. Within a few days four further book prescriptions arrived for me by e-mail. Ella did say that her job is made harder when her clients read a lot, so kudos to her for prescribing books I’d not read – with the one exception of Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, which I love.

As soon as I got back from London I ordered secondhand copies of Heligoland, Jitterbug Perfume and The Artist’s Way, and borrowed Family Matters from the public library the next day. Within a few days four further book prescriptions arrived for me by e-mail. Ella did say that her job is made harder when her clients read a lot, so kudos to her for prescribing books I’d not read – with the one exception of Sebastian Barry’s Days Without End, which I love.

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.

So I’m ambivalent about winter, and was interested to see how the authors collected in Melissa Harrison’s final seasonal anthology would explore its inherent contradictions. I especially appreciated the views of outsiders. Jini Reddy, a Quebec native, calls British winters “a long, grey sigh or a drawn-out ache.” In two of my favorite pieces, Christina McLeish and Nakul Krishna – from Australia and India, respectively – compare the warm, sunny winters they experienced in their homelands with their early experiences in Britain. McLeish remembers finding a disembodied badger paw on a frosty day during one of her first winters in England, while Krishna tells of a time he spent dogsitting in Oxford when all the students were on break. His decorous, timeless prose reminded me of J.R. Ackerley’s.