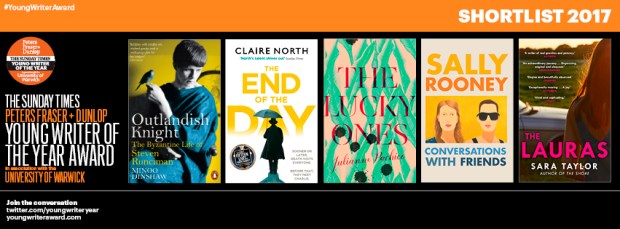

Young Writer of the Year Award Ceremony

Yesterday evening all of us on the Sunday Times / Peters Fraser + Dunlop Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel met up again for the official prize-giving ceremony at the London Library.

My train arrived late and then I got lost, twice (I don’t own a smartphone and hadn’t brought a map – foolish!), so I walked through the door just moments before the prize announcement, but as that was the most important part of the event it didn’t matter in the end. If you haven’t already heard, the prize went to Sally Rooney for Conversations with Friends. She’s the first Irish winner and the joint youngest along with Zadie Smith.

This did not really come as a surprise to the shadow panel, even though we unanimously chose Julianne Pachico’s The Lucky Ones as our winner.

Julianne Pachico is third from left.

Three of us had chosen Rooney’s novel as our runner-up, and when I saw it appear in the Times’ Books of the Year feature, I thought to myself that this was probably a clue. In the official press release, judge and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes, “for line by line quality, emotional complexity, sly sophistication and sheer brio and enjoyment, Sally Rooney’s Conversations with Friends really stood out.”

Judge Elif Shafak states, “I salute Rooney’s intelligent prose, lucid style, and fierce intensity.” Judge Lucy Hughes-Hallett says, “This book stood out for its glittering intelligence, its formal elegance and its capacity to grip the reader. At first reading I was looking forward to bus journeys so that I could read some more. Second time round I was still delighted by the sophistication of its erotic quadrille.”

Being a part of the shadow panel was a wonderful experience and one of the highlights of my literary year.

Novellas in November, Part 1

This is my second year of joining Laura (Reading in Bed) and others in reading mostly novellas in November. I’ve trawled my shelves and my current library pile for short books, limiting myself to ones of around 150 pages or fewer. First up: four short works of fiction. (I’m at work on various ‘nonfiction novellas’, too.) For the first two I give longer reviews as I got the books from the publishers; the other two are true minis.

Swallowing Mercury by Wioletta Greg

(translated from the Polish by Eliza Marciniak)

[146 pages]

I heard about this one via the Man Booker International Prize longlist. Quirkiness is particularly common in indie and translated books, I find, and while it’s often off-putting for me, I loved it here. Greg achieves an impressive balance between grim subject matter and simple enjoyment of remembered childhood activities. Her novella is, after all, set in Poland in the 1980s, the last decade of it being a Communist state in the Soviet Union.

The narrator (and autobiographical stand-in?) is Wiolka Rogalówna, who lives with her parents in a moldering house in the fictional town of Hektary. Her father, one of the most striking characters, was arrested for deserting from the army two weeks before she was born, and now works for a paper mill and zealously pursues his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and taxidermy. The signs of their deprivation – really the whole country’s poverty – are subtle: Wiolka has to go selling hand-picked sour cherries with her grandmother at the market even though she’s embarrassed to run into her classmates; she goes out collecting scrap metal with a gang of boys; and she ties up her hair with a rubber band she cut from an inner tube.

The narrator (and autobiographical stand-in?) is Wiolka Rogalówna, who lives with her parents in a moldering house in the fictional town of Hektary. Her father, one of the most striking characters, was arrested for deserting from the army two weeks before she was born, and now works for a paper mill and zealously pursues his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and taxidermy. The signs of their deprivation – really the whole country’s poverty – are subtle: Wiolka has to go selling hand-picked sour cherries with her grandmother at the market even though she’s embarrassed to run into her classmates; she goes out collecting scrap metal with a gang of boys; and she ties up her hair with a rubber band she cut from an inner tube.

Catholicism plays a major role in these characters’ lives: Wiolka wins a blessed figure in a church raffle, the Pope is rumored to be on his way, and a picture of the Black Madonna visits the town. A striking contrast is set up between the threat of molestation – Wiolka is always fending off unwanted advances, it seems – and lighthearted antics like school competitions and going to great lengths to get rare matchbox labels for her collection. This almost madcap element balances out some of the difficulty of her upbringing.

What I most appreciated was the way Greg depicts some universalities of childhood and adolescence, such as catching bugs, having eerie experiences in the dark, and getting one’s first period. This is a book of titled vignettes of just five to 10 pages, but it feels much more expansive than that, capturing the whole of early life. The Polish title translates as “Unripe,” which better reflects the coming-of-age theme; the English translator has gone for that quirk instead.

A favorite passage:

“Then I sat at the table, which was set with plates full of pasta, laid my head down on the surface and felt the pulsating of the wood. In its cracks and knots, christenings, wakes and name-day celebrations were in full swing, and woodworms were playing dodgeball using poppy seeds that had fallen from the crusts of freshly baked bread.”

Thanks to Portobello Books for the free copy for review.

A Field Guide to the North American Family by Garth Risk Hallberg

[126 pages]

Written somewhat in the style of a bird field guide, this is essentially a set of flash fiction stories you have to put together in your mind to figure out what happens to two seemingly conventional middle-class families: the Harrisons and the Hungates, neighbors on Long Island. Frank Harrison dies suddenly in 2008, and the Hungates divorce soon after. Their son Gabe devotes much of his high school years to drug-taking before an accident lands him in a burn unit. Here he’s visited by his girlfriend, Lacey Harrison. Her little brother, Tommy, is a compulsive liar but knows a big secret his late father was keeping from his wife.

Written somewhat in the style of a bird field guide, this is essentially a set of flash fiction stories you have to put together in your mind to figure out what happens to two seemingly conventional middle-class families: the Harrisons and the Hungates, neighbors on Long Island. Frank Harrison dies suddenly in 2008, and the Hungates divorce soon after. Their son Gabe devotes much of his high school years to drug-taking before an accident lands him in a burn unit. Here he’s visited by his girlfriend, Lacey Harrison. Her little brother, Tommy, is a compulsive liar but knows a big secret his late father was keeping from his wife.

The chapters, each just a paragraph or two, are given alphabetical, cross-referenced headings and an apparently thematic photograph. For example, “Entertainment,” one of my favorite stand-alone pieces, opens “In the beginning was the Television. And the Television was large and paneled in plastic made to look like wood. It dwelled in a dim corner of the living room and came on for national news, Cosby, Saturday cartoons, and football.”

This is a Franzen-esque take on family dysfunction and, like City on Fire, is best devoured in large chunks at a time so you don’t lose momentum: as short as this is, I found it easy to forget who the characters were and had to keep referring to the (handy) family tree at the start. Ultimately I found the mixed-media format just a little silly, and the photos often seem to bear little relation to the text. It’s interesting to see how this idea evolved into the mixed-media sections of City on Fire, which is as epic as this is minimalist, though the story line of this novella is so thin as to be almost incidental.

This is a Franzen-esque take on family dysfunction and, like City on Fire, is best devoured in large chunks at a time so you don’t lose momentum: as short as this is, I found it easy to forget who the characters were and had to keep referring to the (handy) family tree at the start. Ultimately I found the mixed-media format just a little silly, and the photos often seem to bear little relation to the text. It’s interesting to see how this idea evolved into the mixed-media sections of City on Fire, which is as epic as this is minimalist, though the story line of this novella is so thin as to be almost incidental.

Favorite lines:

“Depending on parent genotype, the crossbreeding of a Bad Habit and Boredom will result in either Chemistry or Entertainment.”

“Though hardly the most visible member of its kingdom, Love has never been as endangered as conservationists would have us believe, for without it, the Family would cease to function.”

Thanks to Vintage Books for the free copy for review.

The Comfort of Strangers by Ian McEwan

[100 pages]

This is the earliest McEwan work I’ve read (1981). I could see the seeds of some of his classic themes: obsession, sexual and otherwise; the slow building of suspense and awareness until an inevitable short burst of violence. Mary and Colin are a vacationing couple in Venice. One evening they’ve spent so long in bed that by the time they get out all the local restaurants have shut, but a bar-owner takes pity and gives them sustenance, then a place to rest and wash when they get lost and fail to locate their hotel. Soon neighborly solicitude turns into a creepy level of attention. McEwan has a knack for presenting situations that are just odd enough to stand out but not odd enough to provoke an instant recoil, so along with the characters we keep thinking all will turn out benignly. This reminded me of Death in Venice and The Talented Mr. Ripley.

This is the earliest McEwan work I’ve read (1981). I could see the seeds of some of his classic themes: obsession, sexual and otherwise; the slow building of suspense and awareness until an inevitable short burst of violence. Mary and Colin are a vacationing couple in Venice. One evening they’ve spent so long in bed that by the time they get out all the local restaurants have shut, but a bar-owner takes pity and gives them sustenance, then a place to rest and wash when they get lost and fail to locate their hotel. Soon neighborly solicitude turns into a creepy level of attention. McEwan has a knack for presenting situations that are just odd enough to stand out but not odd enough to provoke an instant recoil, so along with the characters we keep thinking all will turn out benignly. This reminded me of Death in Venice and The Talented Mr. Ripley.

First Love by Gwendoline Riley

[167 pages – on the long side, but I had a library copy to read anyway]

Neve tells us about her testy marriage with Edwyn, a Jekyll & Hyde type who sometimes earns our sympathy for his health problems and other times seems like a verbally abusive misogynist. But she also tells us about her past: her excess drinking, her unpleasant father, her moves between various cities in the north of England and Scotland, a previous relationship that broke down, her mother’s failed marriages, and so on. There’s a lot of very good dialogue in this book – I was reminded of Conversations with Friends – and Neve’s needy mum is a great character, but I wasn’t sure what this all amounts to. As best I can make out, we are meant to question Neve’s self-destructive habits, with Edwyn being just the latest example of a poor, masochistic decision. Every once in a while you get Riley waxing lyrical in a way that suggests she’s a really great author who got stuck with a somber, limited subject: “Outside the sunset abetted one last queer revival of light, so the outlook was torched; wet bus stop, wet shutters, all deep-dyed.”

Neve tells us about her testy marriage with Edwyn, a Jekyll & Hyde type who sometimes earns our sympathy for his health problems and other times seems like a verbally abusive misogynist. But she also tells us about her past: her excess drinking, her unpleasant father, her moves between various cities in the north of England and Scotland, a previous relationship that broke down, her mother’s failed marriages, and so on. There’s a lot of very good dialogue in this book – I was reminded of Conversations with Friends – and Neve’s needy mum is a great character, but I wasn’t sure what this all amounts to. As best I can make out, we are meant to question Neve’s self-destructive habits, with Edwyn being just the latest example of a poor, masochistic decision. Every once in a while you get Riley waxing lyrical in a way that suggests she’s a really great author who got stuck with a somber, limited subject: “Outside the sunset abetted one last queer revival of light, so the outlook was torched; wet bus stop, wet shutters, all deep-dyed.”

Other favorite lines:

“An illusion of freedom: snap-twist getaways with no plans: nothing real. I’d given my freedom away. Time and again. As if I had contempt for it. Or was it hopelessness I felt, that I was so negligent? Or did it hardly matter, in fact? … Could I trust myself? Not to make my life a lair.”

Have you read any of these novellas? Which one takes your fancy?

Talking ’bout My Generation? Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #2

Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist review #2

The first thing to note about a novel with “Conversations” in the title is that there are no quotation marks denoting speech. In a book so saturated with in-person chats, telephone calls, texts, e-mails and instant messages, the lack of speech marks reflects the swirl of voices in twenty-one-year-old Frances’ head; thought and dialogue run together. This is a work in which communication is a constant struggle but words have lasting significance.

It’s the summer between years at uni in Dublin, and Frances is interning at a literary agency and collaborating with her best friend (and ex-girlfriend) Bobbi on spoken word poetry events. She’s the ideas person, and Bobbi brings her words to life. At an open mic night they meet Melissa, an essayist and photographer in her mid-thirties who wants to profile the girls. She invites them back for a drink and Frances, who is from a slightly rough background – divorced parents and an alcoholic father who can’t be relied on to send her allowance – is dazzled by the apparent wealth of Melissa and her handsome actor husband, Nick. Bobbi develops a crush on Melissa, and before too long Frances falls for Nick. The stage is set for some serious amorous complications over the next six months or so.

It’s the summer between years at uni in Dublin, and Frances is interning at a literary agency and collaborating with her best friend (and ex-girlfriend) Bobbi on spoken word poetry events. She’s the ideas person, and Bobbi brings her words to life. At an open mic night they meet Melissa, an essayist and photographer in her mid-thirties who wants to profile the girls. She invites them back for a drink and Frances, who is from a slightly rough background – divorced parents and an alcoholic father who can’t be relied on to send her allowance – is dazzled by the apparent wealth of Melissa and her handsome actor husband, Nick. Bobbi develops a crush on Melissa, and before too long Frances falls for Nick. The stage is set for some serious amorous complications over the next six months or so.

Young woman and older, married man: it may seem like a cliché, but Sally Rooney is doing a lot more here than just showing us an affair. For one thing, this is a coming of age in the truest sense: Frances, forced into independence for the first time, is figuring out who she is as she goes along and in the meantime has to play roles and position herself in relation to other people:

At any time I felt I could do or say anything at all, and only afterwards think: oh, so that’s the kind of person I am.

I couldn’t think of anything witty to say and it was hard to arrange my face in a way that would convey my sense of humour. I think I laughed and nodded a lot.

What will be her rock in the uncertainty? She can’t count on her parents; she alienates Bobbi as often as not; she reads the Gospels out of curiosity but finds no particular solace in religion. Her other challenge is coping with the chronic pain of a gynecological condition. More than anything else, this brings home to her the disappointing nature of real life:

I realised my life would be full of mundane physical suffering, and that there was nothing special about it. Suffering wouldn’t make me special, and pretending not to suffer wouldn’t make me special. Talking about it, or even writing about it, would not transform the suffering into something useful. Nothing would.

Rooney writes in a sort of style-less style that slips right down. There’s a flatness to Frances’ demeanor: she’s always described as “cold” and has trouble expressing her emotions. I recognized the introvert’s risk of coming across as aloof. Before I started this I worried that I’d fail to connect to a novel about experiences so different from mine. I was quite the strait-laced teen and married at 23, so I wasn’t sure I’d be able to relate to Frances and Bobbi’s ‘wildness’. But this is much more about universals than it is about particulars: realizing that you’re stuck with yourself, exploring your sexuality and discovering that sex is its own kind of conversation, and deciding whether ‘niceness’ is really the same as morality.

Rooney writes in a sort of style-less style that slips right down. There’s a flatness to Frances’ demeanor: she’s always described as “cold” and has trouble expressing her emotions. I recognized the introvert’s risk of coming across as aloof. Before I started this I worried that I’d fail to connect to a novel about experiences so different from mine. I was quite the strait-laced teen and married at 23, so I wasn’t sure I’d be able to relate to Frances and Bobbi’s ‘wildness’. But this is much more about universals than it is about particulars: realizing that you’re stuck with yourself, exploring your sexuality and discovering that sex is its own kind of conversation, and deciding whether ‘niceness’ is really the same as morality.

With its prominent dialogue and discrete scenes, I saw the book functioning like a minimalist play, and I could also imagine it working as an on-location television miniseries. In some ways the dynamic between Frances and Bobbi mirrors that between the main characters in Paulina and Fran by Rachel B. Glaser, Friendship by Emily Gould, and The Animators by Kayla Rae Whitaker, so if you enjoyed any of those I highly recommend this, too. Rooney really captures the angst of youth:

You’re twenty-one, said Melissa. You should be disastrously unhappy.

I’m working on it, I said.

This is a book I was surprised to love, but love it I did. Rooney is a tremendous talent whose career we’ll have the privilege to watch unfolding. I’ve told the shadow panel that if we decide our focus is on the “Young” in Young Writer, there’s no doubt that this nails the zeitgeist and should win.

The conversations even spill out onto the endpapers.

Reviews of Conversations with Friends:

From the shadow panel:

Annabel’s at Annabookbel

Clare’s at A Little Blog of Books

Dane’s at Social Book Shelves

Eleanor’s at Elle Thinks

Others:

Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty: In MacLaverty’s quietly beautiful fifth novel, a retired couple faces up to past trauma and present incompatibility during a short vacation in Amsterdam. My overall response was one of admiration for what this couple has survived and sympathy for their current situation – with hope that they’ll make it through this, too. (Reviewed for

Midwinter Break by Bernard MacLaverty: In MacLaverty’s quietly beautiful fifth novel, a retired couple faces up to past trauma and present incompatibility during a short vacation in Amsterdam. My overall response was one of admiration for what this couple has survived and sympathy for their current situation – with hope that they’ll make it through this, too. (Reviewed for

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: The residents of Georgetown cemetery limbo don’t know they’re dead – or at least won’t accept it. An entertaining and truly original treatment of life’s transience; I know it’s on every other best-of-year list out there, but it really is a must-read.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders: The residents of Georgetown cemetery limbo don’t know they’re dead – or at least won’t accept it. An entertaining and truly original treatment of life’s transience; I know it’s on every other best-of-year list out there, but it really is a must-read.

A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin: Tomalin is best known as a biographer of literary figures including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, but her memoir is especially revealing about the social and cultural history of the earlier decades her life covers. A dignified but slightly aloof book – well worth reading for anyone interested in spending time in London’s world of letters in the second half of the twentieth century.

A Life of My Own by Claire Tomalin: Tomalin is best known as a biographer of literary figures including Mary Wollstonecraft, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, but her memoir is especially revealing about the social and cultural history of the earlier decades her life covers. A dignified but slightly aloof book – well worth reading for anyone interested in spending time in London’s world of letters in the second half of the twentieth century. Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward: The story of a mixed-race family haunted – both literally and figuratively – by the effects of racism, drug abuse and incarceration in Bois Sauvage, a fictional Mississippi town. Beautiful language; perfect for fans of Toni Morrison and Cynthia Bond.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward: The story of a mixed-race family haunted – both literally and figuratively – by the effects of racism, drug abuse and incarceration in Bois Sauvage, a fictional Mississippi town. Beautiful language; perfect for fans of Toni Morrison and Cynthia Bond. What It Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Reviewed for

What It Means when a Man Falls from the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah (Reviewed for  The Education of a Coroner by John Bateson: The coroner’s career is eventful no matter what, but Marin County, California has its fair share of special interest, what with Golden Gate Bridge suicides, misdeeds at San Quentin Prison, and various cases involving celebrities (e.g. Harvey Milk, Jerry Garcia and Tupac) in addition to your everyday sordid homicides. Ken Holmes was a death investigator and coroner in Marin County for 36 years; Bateson successfully recreates Holmes’ cases with plenty of (sometimes gory) details.

The Education of a Coroner by John Bateson: The coroner’s career is eventful no matter what, but Marin County, California has its fair share of special interest, what with Golden Gate Bridge suicides, misdeeds at San Quentin Prison, and various cases involving celebrities (e.g. Harvey Milk, Jerry Garcia and Tupac) in addition to your everyday sordid homicides. Ken Holmes was a death investigator and coroner in Marin County for 36 years; Bateson successfully recreates Holmes’ cases with plenty of (sometimes gory) details. Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker: Tasting notes: gleeful, ebullient, learned, self-deprecating; suggested pairings: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler; Top Chef, The Great British Bake Off. A delightful blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine.

Cork Dork by Bianca Bosker: Tasting notes: gleeful, ebullient, learned, self-deprecating; suggested pairings: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler; Top Chef, The Great British Bake Off. A delightful blend of science, memoir and encounters with people who are deadly serious about wine. A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light, edited by Eleanor Brown: A highly enjoyable set of 18 autobiographical essays that celebrate what’s wonderful about the place but also acknowledge disillusionment; highlights are from Maggie Shipstead, Paula McLain, Therese Anne Fowler, Jennifer Coburn, Julie Powell and Michelle Gable. If you have a special love for Paris, have always wanted to visit, or just enjoy armchair traveling, this collection won’t disappoint you.

A Paris All Your Own: Bestselling Women Writers on the City of Light, edited by Eleanor Brown: A highly enjoyable set of 18 autobiographical essays that celebrate what’s wonderful about the place but also acknowledge disillusionment; highlights are from Maggie Shipstead, Paula McLain, Therese Anne Fowler, Jennifer Coburn, Julie Powell and Michelle Gable. If you have a special love for Paris, have always wanted to visit, or just enjoy armchair traveling, this collection won’t disappoint you. Ashland & Vine by John Burnside: Essentially, it’s about the American story, individual American stories, and how these are constructed out of the chaos and violence of the past – all filtered through a random friendship that forms between a film student and an older woman in the Midwest. This captivated me from the first page.

Ashland & Vine by John Burnside: Essentially, it’s about the American story, individual American stories, and how these are constructed out of the chaos and violence of the past – all filtered through a random friendship that forms between a film student and an older woman in the Midwest. This captivated me from the first page. Tragic Shores: A Memoir of Dark Travel, Thomas H. Cook: In 28 non-chronological chapters, Cook documents journeys he’s made to places associated with war, massacres, doomed lovers, suicides and other evidence of human suffering. This is by no means your average travel book and it won’t suit those who seek high adventure and/or tropical escapism; instead, it’s a meditative and often melancholy picture of humanity at its best and worst. (Reviewed for

Tragic Shores: A Memoir of Dark Travel, Thomas H. Cook: In 28 non-chronological chapters, Cook documents journeys he’s made to places associated with war, massacres, doomed lovers, suicides and other evidence of human suffering. This is by no means your average travel book and it won’t suit those who seek high adventure and/or tropical escapism; instead, it’s a meditative and often melancholy picture of humanity at its best and worst. (Reviewed for  The Valentine House by Emma Henderson: This is a highly enjoyable family saga set mostly between 1914 and 1976 at an English clan’s summer chalet in the French Alps near Geneva, with events seen from the perspective of a local servant girl. You can really imagine yourself into all the mountain scenes and the book moves quickly –a great one to take on vacation.

The Valentine House by Emma Henderson: This is a highly enjoyable family saga set mostly between 1914 and 1976 at an English clan’s summer chalet in the French Alps near Geneva, with events seen from the perspective of a local servant girl. You can really imagine yourself into all the mountain scenes and the book moves quickly –a great one to take on vacation.

The 2017 Book Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman. (See

The 2017 Book Everybody Else Loved but I Didn’t: Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman. (See  The Downright Strangest Book I Read This Year: An English Guide to Birdwatching by Nicholas Royle.

The Downright Strangest Book I Read This Year: An English Guide to Birdwatching by Nicholas Royle. The Best First Line of the Year: “History has failed us, but no matter.” (Pachinko, Min Jin Lee)

The Best First Line of the Year: “History has failed us, but no matter.” (Pachinko, Min Jin Lee)

Claire North, aka “Cat” (real name: Catherine Webb; her fantasy and science fiction books are under various names) was in a way the odd one out at this event. Collins opened by saying that this award is all about getting in on the ground level with these writers, several of whom are debut authors. But North is a teen phenom who published her first book at age 14 and is set to release #20 next year. All along her parents called her a freak and demanded that she get her GCSEs and go to uni because writing “isn’t a proper job” (“but we’re very proud of you!” they’d usually append). She’s experienced the full gamut of responses over the years: some swore she wouldn’t have anything to say until age 40; others sighed that once she turned 18 she could no longer be marketed as “young.” She read the perfect passage from The End of the Day: a frantic, bravura account of the riders of the apocalypse together on a plane. She loves that science fiction “makes the extraordinary domestic” and playing with death appealed to her “flippant nature.” Charlie is, she thinks, the kindest character she’s ever written.

Claire North, aka “Cat” (real name: Catherine Webb; her fantasy and science fiction books are under various names) was in a way the odd one out at this event. Collins opened by saying that this award is all about getting in on the ground level with these writers, several of whom are debut authors. But North is a teen phenom who published her first book at age 14 and is set to release #20 next year. All along her parents called her a freak and demanded that she get her GCSEs and go to uni because writing “isn’t a proper job” (“but we’re very proud of you!” they’d usually append). She’s experienced the full gamut of responses over the years: some swore she wouldn’t have anything to say until age 40; others sighed that once she turned 18 she could no longer be marketed as “young.” She read the perfect passage from The End of the Day: a frantic, bravura account of the riders of the apocalypse together on a plane. She loves that science fiction “makes the extraordinary domestic” and playing with death appealed to her “flippant nature.” Charlie is, she thinks, the kindest character she’s ever written. Sara Taylor read from one of Ma’s earliest stories about how her parents met. She wrote The Lauras while she was supposed to be completing her PhD thesis on censorship in American literature. At the time she was coming to terms with the fact that she was going to be staying in the UK, as well as remembering family road trips and aspects of her relationship with her mother that she wishes were otherwise. Her agent wasn’t comfortable with the focus on an “agender” character, but Taylor held firm. She’s used to ignoring the advice her (older, male) professors and advisors tend to give her. Instead, she gets tips from her ten-years-younger sister back in the States, who knows exactly how to “fix” her work. Taylor feels the USA is 5–10 years behind the UK on gender issues, and revealed that The Lauras is a response to the novel Love Child (1971) by Maureen Duffy. She has recently finished her third novel and hopes to get back into teaching since writing non-stop for nine months makes her “go a little funny.”

Sara Taylor read from one of Ma’s earliest stories about how her parents met. She wrote The Lauras while she was supposed to be completing her PhD thesis on censorship in American literature. At the time she was coming to terms with the fact that she was going to be staying in the UK, as well as remembering family road trips and aspects of her relationship with her mother that she wishes were otherwise. Her agent wasn’t comfortable with the focus on an “agender” character, but Taylor held firm. She’s used to ignoring the advice her (older, male) professors and advisors tend to give her. Instead, she gets tips from her ten-years-younger sister back in the States, who knows exactly how to “fix” her work. Taylor feels the USA is 5–10 years behind the UK on gender issues, and revealed that The Lauras is a response to the novel Love Child (1971) by Maureen Duffy. She has recently finished her third novel and hopes to get back into teaching since writing non-stop for nine months makes her “go a little funny.”