Some 2024 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Bee Sting by Paul Murray

Shortest books read this year: The Wood at Midwinter by Susanna Clarke – a standalone short story (unfortunately, it was kinda crap); After the Rites and Sandwiches by Kathy Pimlott – a poetry pamphlet

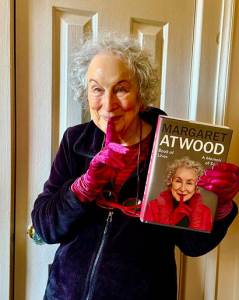

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Authors I read the most by this year: Alice Oseman (5 rereads), Carol Shields (3 rereads); Margaret Atwood, Rachel Cusk, Pam Houston, T. Kingfisher, Sarah Manguso, Maggie O’Farrell, and Susan Allen Toth (2 each)

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints,) Carcanet (15), Bloomsbury & Faber (12 each), Alice James Books & Picador/Pan Macmillan (9 each)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year: Sherman Alexie and Bernardine Bishop

Proudest bookish achievements: Reading almost the entire Carol Shields Prize longlist; seeing The Bookshop Band on their huge Emerge, Return tour and not just getting my photo with them but having it published on both the Foreword Reviews and Shelf Awareness websites

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Getting a chance to judge published debut novels for the McKitterick Prize

Books that made me laugh: Lots, but particularly Fortunately, the Milk… by Neil Gaiman, The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs, and You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here by Benji Waterhouse

Books that made me cry: On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan, My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Two books that hit the laughing-and-crying-at-the-same-time sweet spot: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie and I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

Best book club selections: Clear by Carys Davies, Howards End by E.M. Forster, Strange Sally Diamond by Liz Nugent

Best first lines encountered this year:

- From Cocktail by Lisa Alward: “The problem with parties, my mother says, is people don’t drink enough.”

- From A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg: “Oh, the games families play with each other.”

- From The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham: “A celestial light appeared to Barrett Meeks in the sky over Central Park, four days after Barrett had been mauled, once again, by love.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”

From The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley: “Forgiveness and hope are miracles. They let you change your life. They are time-travel.”- From Mammoth by Eva Baltasar: “May I know to be alert when, at the stroke of midnight, life sends me its cavalry.”

- From Private Rites by Julia Armfield: “For now, they stay where they are and listen to the unwonted quiet, the hush in place of rainfall unfamiliar, the silence like a final snuffing out.”

- From Come to the Window by Howard Norman: “Wherever you sit, so sit all the insistences of fate. Still, the moment held promise of a full life.”

- From Intermezzo by Sally Rooney: “It doesn’t always work, but I do my best. See what happens. Go on in any case living.”

- From Barrowbeck by Andrew Michael Hurley: “And she thought of those Victorian paintings of deathbed scenes: the soul rising vaporously out of a spent and supine body and into a starry beam of light; all tears wiped away, all the frailty and grossness of a human life transfigured and forgiven at last.”

- From Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: “Pure life.”

Books that put a song in my head every time I picked them up: I’m the King of the Castle by Susan Hill (“Crash” by Dave Matthews Band); Y2K by Colette Shade (“All Star” by Smashmouth)

Shortest book titles encountered: Feh (Shalom Auslander) and Y2K (Colette Shade), followed by Keep (Jenny Haysom)

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best 2024 book titles: And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound, I Can Outdance Jesus, Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Best book titles from other years: Recipe for a Perfect Wife, Tripping over Clouds, Waltzing the Cat, Dressing Up for the Carnival, The Met Office Advises Caution

Favourite title and cover combo of the year: I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol

Best punning title (and nominative determinism): Knead to Know: A History of Baking by Dr Neil Buttery

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

Biggest disappointments: The Glassmaker by Tracy Chevalier (I didn’t get past the first chapter because of all the info dumping from her research); The Year of the Cat by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett; milk and honey by Rupi Kaur (that … ain’t poetry); 2 from the Observer’s 10 best new novelists feature (here and here)

A couple of 2024 books that everyone was reading but I decided not to: Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, You Are Here by David Nicholls

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The worst books I read this year: Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, A Spy in the House of Love by Anaïs Nin

The downright strangest books I read this year: Zombie Vomit Mad Libs, followed by The Peculiar Life of a Lonely Postman. All Fours by Miranda July (I am at 44% now) is pretty weird, too.

Doorstopper of the Month: The Absolute Book by Elizabeth Knox (2019)

Epic fantasy is far from my usual fare, but this was a book worth getting lost in. The reading experience reminded me of what I had with A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami, or perhaps Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke – though it’s possible this last association was only in my mind because of Dan Kois. You see, we have Kois, an editor at Slate, to thank for this novel being published outside of Knox’s native New Zealand. He wrote an enthusiastic Slate review of an amazing novel he’d found that was only available through a small university press, and Clarke’s novel was his main point of reference. How’s that for the power of a book review?

Taryn Cornick, 33, has adapted her PhD thesis into a popular history of libraries – the search for absolute knowledge; the perennial threats that libraries face, from budget cuts to burnings – that she’s been discussing at literary festivals around the world. One particular burning looms large in her family’s history: the library at her grandfather’s country estate near the border of England and Wales, Princes Gate. As girls, Taryn and her older sister, Beatrice, helped to raise the alarm and saved the bulk of their grandfather’s collection. But one key artifact has been missing ever since: the Firestarter, an ancient scroll box that is said to have been through five fires and will survive another arson attempt before the book is through.

Nearly 15 years ago now, Beatrice was the victim of a random act of violence. Soon after her killer was released from prison, he turned up dead in unusual circumstances. Ever since, Detective Inspector Jacob Berger has suspected that Taryn arranged a revenge killing, but he has no proof. His cold case heats back up when Taryn lands in the hospital and complains of a series of prank calls.

What ensues is complicated, but in essence, the ongoing fallout of Beatrice’s murder and a cosmic battle over the Firestarter are twin forces that plunge Taryn and Jacob into the faerie realm (Sidh). Their guide to the Sidh is Shift, a shapeshifter who can create impromptu gates between the two worlds (while others, like Princes Gate, are permanent passageways).

Fairies (sidhe), demons, talking ravens … there’s some convoluted world-building here, and when I reached the end I realized I still had many ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, though often this was because I hadn’t paid close enough attention and if I glanced back I’d see that Knox did indeed tell us how characters got from A to B, and who was after the Firestarter and why.

The book travels everywhere from Provence to Purgatory, but I particularly liked the descriptions of the primitive lifestyle in the faerie realm. Knox gives enough detail about things like food and clothing that you can really imagine yourself into each setting, and there’s the occasional funny turn of phrase that inserts the magical into everyday life in a tongue-in-cheek way, like “The Nespresso [machine] made hatching-dragon sounds.”

My two favorite scenes were an intense escape from a marsh and one that delightfully blends the human world and faerie: Taryn’s father, Basil Cornick, is a Kiwi actor best known for his role in a Game of Thrones-style television show. He’s roped into what he thinks is a screen test, playing Odin opposite a very convincing animatronic monster and pair of talking birds. We and Taryn know what he doesn’t: that he was used to negotiate with a real demon. The terrific epilogue also offers an appealing vision of how the sidhe might save the world.

If, like me, all you know of Knox’s previous work is the bizarre and kind of awful The Vintner’s Luck (which I read for a book club a decade or so ago), you’ll be intrigued to learn that angels play a role here, too. But beneath all the magical stuff, which is sometimes hard to follow or believe in, the novel is a hymn to language and libraries. A number of books are mentioned, starting with the one that was in Beatrice’s backpack at the time of her death: “the blockbuster of that year, 2003, a novel about tantalising, epoch-spanning conspiracies. Beatrice enjoyed those books, perhaps because they were often set in libraries.” (That’s The Da Vinci Code, of course.) Also mentioned: Labyrinth by Kate Mosse, the Moomin books, and the film Spirited Away – no doubt these were beloved influences for Knox.

I appreciated the words about libraries’ enduring value, even on a poisoned planet. “I want there to be libraries in the future. I want today to give up being so smugly sure about what tomorrow won’t need,” Taryn says. She knows that, for this to happen, people must “care about the transmission of knowledge from generation to generation, and about keeping what isn’t immediately necessary because it might be vital one day. Or simply intriguing, or beautiful.” That’s an analogy for species, too, I think, and a reminder of our responsibility: to preserve human accomplishments, yes, but also the more-than-human world (even if that ‘more’ might not include fairies).

Page count: 626 (my only 500+-page doorstopper so far this year!)

My rating:

Women’s Prize Longlist Reviews (Leilani, Lockwood, and Lyon) & Predictions

Tomorrow, Wednesday the 28th, the Women’s Prize shortlist will be revealed. I have read just over half of the longlist so far and have a few more of the nominees on order from the library – though I may cancel one or two of my holds if they don’t advance to the shortlist. Also, my neighbourhood book club has applied to be one of six reading groups shadowing the shortlist this year via a Reading Agency initiative. If I do say so myself, I think we put in a rather strong application. We’ll hear later this week if we’ve been chosen – fingers crossed!

The three longlisted novels I’ve read most recently were all by L authors:

Luster by Raven Leilani

Edie’s voice is immediately engaging: cutting, funny, pithy. It reminded me of Ava’s in a fellow Women’s Prize nominee, Exciting Times, and both novels even employ a near-identical metaphor: “I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat” (Dolan) versus “all the kids stacked underneath my trench coat rejoice” (Leilani). They are also both concerned with how young women negotiate a confusing romantic landscape and look for meaning beyond a dead-end career. The African-American Edie’s entry-level work for a New York City publisher barely covers her rent at a squalid shared apartment. She’s shagged every male in the office and is now on to one she met online: Eric, a white, middle-aged archivist with an open marriage and a Black adopted daughter.

Edie’s voice is immediately engaging: cutting, funny, pithy. It reminded me of Ava’s in a fellow Women’s Prize nominee, Exciting Times, and both novels even employ a near-identical metaphor: “I wondered if Victoria was a real person or three Mitford sisters in a long coat” (Dolan) versus “all the kids stacked underneath my trench coat rejoice” (Leilani). They are also both concerned with how young women negotiate a confusing romantic landscape and look for meaning beyond a dead-end career. The African-American Edie’s entry-level work for a New York City publisher barely covers her rent at a squalid shared apartment. She’s shagged every male in the office and is now on to one she met online: Eric, a white, middle-aged archivist with an open marriage and a Black adopted daughter.

As Edie insinuates herself into Eric’s suburban New Jersey life in peculiar and sometimes unwitting ways, we learn more about her traumatic past: Both of her parents are dead, one by suicide, and she had an abortion at age 16. Along with sex, her main escape is her painting, which is described in tender detail. There are a number of amusing scenes set at off-the-wall locations, like a theme park, a clown school, and Comic Con. Leilani has a knack for capturing an entire realm of experience in just a few pages, as when she satirizes current publishing trends or encapsulates what it’s like to be a bicycle delivery person.

But, as a Goodreads acquaintance put it, all this sharp writing is rather wasted on the plot. I found the direction of the book in its second half utterly unrealistic, and never believed that Edie would have found Eric attractive in any way. (His interest in her is beyond creepy, really.) What I found most intriguing, along with the painting hobby, were Edie’s interactions with other Black characters, such as a publishing company colleague and Eric’s adopted daughter – there’s an uncomfortable sense that they should have a natural camaraderie and/or that Edie should be some kind of role model. I might have liked more of that dynamic, instead of the unbearable awkwardness of temporary instalment in a white neighbourhood. Other readalikes: Queenie, Here Is the Beehive, and On Beauty.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

Priestdaddy is one of my absolute favourite books, so Lockwood’s debut novel was one of the 2021 releases I was most looking forward to reading. It took me a while to warm to, but ultimately did not disappoint. It probably helped that I was familiar with the author’s iconoclastic sense of humour. This is a work of third-person autofiction – much more so than I’d realized before I read the Acknowledgments – and to start with it feels like a flippant skewering of modern life, which for some is all about online personality and performance. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.”

Priestdaddy is one of my absolute favourite books, so Lockwood’s debut novel was one of the 2021 releases I was most looking forward to reading. It took me a while to warm to, but ultimately did not disappoint. It probably helped that I was familiar with the author’s iconoclastic sense of humour. This is a work of third-person autofiction – much more so than I’d realized before I read the Acknowledgments – and to start with it feels like a flippant skewering of modern life, which for some is all about online personality and performance. A woman who became a social media star by tweeting quips like “Can a dog be twins?” reflects on life on “the portal” and under “the dictator.”

Midway through the book, she receives a wake-up call in the form of texts from her mother summoning her back to the Midwest for a family emergency. “It was a marvel how cleanly and completely this lifted her out of the stream of regular life.” Shit just got real, as they say. But “Would it change her?” she asks herself. Apparently, this very thing happened to Lockwood’s own family, which accounts for how heartfelt the second half is – still funny, but with an ache behind it, the same that I sensed and loved in Priestdaddy.

It is the about-face that makes this novel, forcing readers to question the value of a digital existence based on glib pretence. As the protagonist tells her students at one point, “Your attention is holy,” and with life so fragile there is no time to waste. What Lockwood is trying to do here is even bigger than that, though, I think. She mocks the whole idea of plot yet takes up the mantle of the “social novel,” as if creating a new format for the Internet-age novel in short, digestible sections. I’m not sure this is as earth-shattering as all that, but it is entertaining and deceptively deep. It also feels like a very current book, playing the role that Weather did in last year’s Women’s Prize race. (See my Goodreads review for more quotes, spoiler-y discussion, and why this book held personal poignancy for me.)

Consent by Annabel Lyon

I’m always drawn to stories of sisters and this was an intriguing one, though the jacket text sets it up to be more of a thriller than it actually is. After their mother’s death, Sara, a medical ethicist, looks after Mattie, her intellectually disabled sister. When Mattie is lured into eloping, Sara’s protective instinct goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, Saskia, a graduate student in French literature, feels obliged to put her twin sister Jenny’s needs first after a car accident leaves Jenny in a coma. There are two decades separating the sets of sisters, but aspects of their experiences reverberate, with fashion, perfume, and alcoholism appearing as connecting elements even before a more concrete link emerges.

I’m always drawn to stories of sisters and this was an intriguing one, though the jacket text sets it up to be more of a thriller than it actually is. After their mother’s death, Sara, a medical ethicist, looks after Mattie, her intellectually disabled sister. When Mattie is lured into eloping, Sara’s protective instinct goes into overdrive. Meanwhile, Saskia, a graduate student in French literature, feels obliged to put her twin sister Jenny’s needs first after a car accident leaves Jenny in a coma. There are two decades separating the sets of sisters, but aspects of their experiences reverberate, with fashion, perfume, and alcoholism appearing as connecting elements even before a more concrete link emerges.

For much of the novel, Lyon bounces between the two storylines. I occasionally confused Sara and Saskia, but I think that’s part of the point (why else would an author select two S-a names?) – their stories overlap as they find themselves in the position of making decisions on behalf of an incapacitated sister. The title invites deliberation about how control is parcelled out in these parallel situations, but I’m not sure consent was the right word to encapsulate the whole plot; it seems to give too much importance to some fleeting sexual relationships.

At times I found Lyon’s prose repetitive or detached, but I enjoyed the overall dynamic and the medical threads. There are some stylish lines that land perfectly, like “There she goes … in her lovely coat, that cashmere-and-guilt blend so few can afford. That lovely perfume she trails, lilies and guilt.” The Vancouver setting and French–English bilingualism, not things I often encounter in fiction, were also welcome, and the last few chapters are killer.

The other nominees I’ve read, with ratings and links to reviews, are:

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller

The rest of the longlist is:

- Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers – I might read this from the library.

- The Golden Rule by Amanda Craig – I’d thought I’d give this one a miss, but I recently found a copy in a Little Free Library. My plan is to read it later in the year as part of a Patricia Highsmith kick, but I’ll move it up the stack if it makes the shortlist.

- Because of You by Dawn French – Not a chance. Right? Please!

- How the One-Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones – A DNF; I would only try it again from the library if it was shortlisted.

- Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon – I might read this from the library.

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters – I will definitely read this from the library.

- Summer by Ali Smith – I struggle with her work and haven’t enjoyed this series; I would only read this if it was shortlisted and my book club was assigned it!

My ideal shortlist (a wish list based on my reading and what I still want to read):

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

- No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

vs.

My predicted shortlist and reasoning:

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett – A dead cert. I’ve said so since I reviewed it in June 2020.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett – A dead cert. I’ve said so since I reviewed it in June 2020.- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi – Others don’t seem to fancy Doshi’s chances, and it’s true that she was already shortlisted for the Booker, but I feel like this could be more unifying a choice for the judges than, e.g. Clarke or Lockwood.

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi – Another definite.

- Luster by Raven Leilani – Not as strong as the Dolan, in my opinion, but it seems to have a lot of love from these judges (especially Vick Hope, who emphasized how perfectly it captured what it’s like to be young today), and from critics generally.

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters – Ordinarily I would have said the Prize is too staid to shortlist a trans author, but after all the online abuse that has been directed at Peters, I think the judges will want to make a stand in support of her legitimacy.

- Summer by Ali Smith – The most establishment author on the list, and not one I generally care for, but this would be a way of recognizing the four-part Seasons opus and her work in general. Of the middle-aged white cohort, she seems most likely.

I will happily accept some mixture of my wished-for and predicted titles, and would be surprised if any of the five books I have not mentioned is shortlisted. (Though quite a few others are predicting that Claire Fuller will advance; I’d have no problem with that.) I don’t think my book club would get a say in which of the six titles we’d be sent to read for the shadowing project, which is risky as I may have already read it and not want to reread, or it may be a surprise nominee that I don’t want to read, but I’ll cross that bridge if we come to it.

Callum, Eric, Laura and Rachel have been posting lots of reviews and thoughts related to the Women’s Prize. Have a look at their blogs!

Rachel also produced a priceless spreadsheet of all the Prize nominees by year, so you can tick off the ones you’ve read. I’m up to 150 now!

Women’s Prize 2021: Predictions & Eligible Titles

In previous years I’ve been a half-hearted follower of the Women’s Prize – often half or more of the longlist doesn’t interest me – but given that nearly two-thirds of my annual reading is by women, and that I so enjoyed catching up on the previous winners last year, I somehow feel more invested this year. Following literary prizes is among my greatest bookish joys, so this time round I’ve made more of an effort to look back through a year of UK fiction releases by women, whether I’ve read the books or not, and make some informed predictions.

Here is the scope of the prize: “Any woman writing in English – whatever her nationality, country of residence, age or subject matter – is eligible. Novels must be published in the United Kingdom between 1 April in the year the Prize calls for entries, and 31 March the following year, when the Prize is announced.” (Note: no novellas or short stories; the judges are looking for the best work by a woman – or a trans person legally defined as a woman.)

Based on the books by women that I have admired, loved, or found most relevant in 2020‒21, here are my predictions for the longlist, which will be revealed on March 10th (two weeks from today) and will contain 16 titles. I’ve aimed for a balance between new and established voices, and a mix of genres. I link to my reviews where available.

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

- Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

- Sisters by Daisy Johnson

- Pew by Catherine Lacey

- No One Is Talking about This by Patricia Lockwood – currently reading

- A Burning by Megha Majumdar*

- The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

- Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley**

- Outlawed by Anna North

- Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud

- The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey***

- The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams

* Not read yet. It seems like this year’s Home Fire.

** Not read yet, but I loved Elmet so much that I’m confident this will be a hit with me, too.

*** Not read yet. I plan to read it, but after its Costa win there’s a long library holds queue.

Note: “The Prize only accepts novels entered by publishers, who may each submit a maximum of two titles per imprint and one title for imprints with a list of five fiction titles or fewer published in a year. Previously shortlisted and winning authors are awarded a ‘free pass’ in addition to a publisher’s general submissions.”

- Because of all the funds the publishers are expected to contribute to the Prize’s publicity at each level of judging, the process unfairly discriminates against small, independent publishers.

Bernardine Evaristo is the chair of judges this year, so I expect a strong showing from BIPOC and LGBTQ authors AND a leaning towards experimental prose, probably even more so than my above list reflects.

Other novels I considered:

Runners-up – books that I enjoyed and would be perfectly happy to see nominated:

- Milk Fed by Melissa Broder – not reviewed yet

- Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan

- The Group by Lara Feigel

- Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller – not reviewed yet

- Artifact by Arlene Heyman

- The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd

- A Town Called Solace by Sue Lawson – not reviewed yet

- Monogamy by Sue Miller

- What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez

- Islands of Mercy by Rose Tremain

Reads that didn’t match up for me, but would be eligible:

- When the Lights Go Out by Carys Bray

- The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

- Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey

- The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney (DNF)

- The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin

- Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce

- The Animals in That Country by Laura Jean McKay

- Scenes of a Graphic Nature by Caroline O’Donoghue

- True Story by Kate Reed Petty (DNF)

- Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld

- The Lamplighters by Emma Stonex – currently reading

- Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler

- little scratch by Rebecca Watson

- Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson

Haven’t had a chance to read yet / don’t have access to, so can only list without comment (most likely alternative nominees in bold):

- Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa

- You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

- The Push by Ashley Audrain

- If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

- [The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi] – Update: would not be eligible according to the new requirement that trans people be legally defined as female; before that regulation was in place, Emezi was longlisted for Freshwater.

- Sea Wife by Amity Gaige

- The Wild Laughter by Caoilinn Hughes

- How We Are Translated by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson

- Consent by Annabel Lyon

- A Crooked Tree by Una Mannion

- The Last Migration by Charlotte McConaghy

- The Art of Falling by Danielle McLaughlin

- His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

- A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa

- Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

- Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler

- An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson – gets a “free pass” entry as MR is a previous winner

- Belladonna by Anbara Salam

- Kololo Hill by Neema Shah

- All Adults Here by Emma Straub

- Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan

- Saving Lucia by Anna Vaught

- We Are All Birds of Uganda by Hafsa Zayyan

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang

I overlapped with this Goodreads list (which I didn’t look at until after compiling mine) on 28 titles. It erroneously includes The Anthill by Julianne Pachico – not released in the UK until May 2021 – but otherwise has another nearly 50, mostly solid, ideas, such as Luster by Raven Leilani, Blue Ticket by Sophie Mackintosh, and Death in her Hands by Ottessa Moshfegh.

See also Laura’s and Rachel’s predictions.

Any predictions or wishes for the Women’s Prize longlist?

Book Serendipity in the Final Months of 2020

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. (Earlier incidents from the year are here, here, and here.)

- Eel fishing plays a role in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson.

- A girl’s body is found in a canal in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and Carrying Fire and Water by Deirdre Shanahan.

- Curlews on covers by Angela Harding on two of the most anticipated nature books of the year, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn (and both came out on September 3rd).

- Thanksgiving dinner scenes feature in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid.

- A gay couple has the one man’s mother temporarily staying on the couch in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Memorial by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading two “The Gospel of…” titles at once, The Gospel of Eve by Rachel Mann and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson (and I’d read a third earlier in the year, The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving).

- References to Dickens’s David Copperfield in The Cider House Rules by John Irving and Mudbound by Hillary Jordan.

- The main female character has three ex-husbands, and there’s mention of chin-tightening exercises, in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer.

- A Welsh hills setting in On the Red Hill by Mike Parker and Along Came a Llama by Ruth Janette Ruck.

- Rachel Carson and Silent Spring are mentioned in A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee, The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson. SS was also an influence on Losing Eden by Lucy Jones, which I read earlier in the year.

- There’s nude posing for a painter or photographer in The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel, How to Be Both by Ali Smith, and Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- A weird, watery landscape is the setting for The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey and Piranesi by Susanna Clarke.

- Bawdy flirting between a customer and a butcher in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Just Like You by Nick Hornby.

- Corbels (an architectural term) mentioned in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver.

- Near or actual drownings (something I encounter FAR more often in fiction than in real life, just like both parents dying in a car crash) in The Idea of Perfection, The Glass Hotel, The Gospel of Eve, Wakenhyrst, and Love and Other Thought Experiments.

- Nematodes are mentioned in The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A toxic lake features in The New Wilderness by Diane Cook and Real Life by Brandon Taylor (both were also on the Booker Prize shortlist).

- A black scientist from Alabama is the main character in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- Graduate studies in science at the University of Wisconsin, and rivals sabotaging experiments, in Artifact by Arlene Heyman and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A female scientist who experiments on rodents in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Artifact by Arlene Heyman.

- There are poems about blackberrying in Dearly by Margaret Atwood, Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols, and How to wear a skin by Louisa Adjoa Parker. (Nichols’s “Blackberrying Black Woman” actually opens with “Everyone has a blackberry poem. Why not this?” – !)

I gave some initial thoughts about the book

I gave some initial thoughts about the book

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

This is a mash-up of the campus novel, the Victorian pastiche, and the time travel adventure. Ariel Manto is a PhD student working on thought experiments. Inciting incidents come thick and fast: her supervisor disappears, the building that houses her office partially collapses as it’s on top of an old railway tunnel, and she finds a copy of Thomas Lumas’s vanishingly rare The End of Mr. Y in a box of mixed antiquarian stock going for £50 at a secondhand bookshop. Rumour has it the book is cursed, and when Ariel realises that the key page – giving a Victorian homoeopathic recipe for entering the “Troposphere,” a dream/thought realm where one travels through time and space – has been excised, she knows the quest has only just begun. It will involve the book within a book, Samuel Butler novels, a theologian and a shrine, lab mice plus the God of Mice, and a train line whose destinations are emotions.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African-American twins’ paths divide in 1950s Louisiana. Perceptive and beautifully written, this has characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent.

The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett: Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity. Light-skinned African-American twins’ paths divide in 1950s Louisiana. Perceptive and beautifully written, this has characters whose struggles feel genuine and pertinent. Piranesi by Susanna Clarke: To start with, Piranesi traverses his watery labyrinth like he’s an eighteenth-century adventurer, his resulting notebooks reading rather like Alexander von Humboldt’s writing. I admired how the novel moved from the fantastical and abstract into the real and gritty. Read it even if you say you don’t like fantasy.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke: To start with, Piranesi traverses his watery labyrinth like he’s an eighteenth-century adventurer, his resulting notebooks reading rather like Alexander von Humboldt’s writing. I admired how the novel moved from the fantastical and abstract into the real and gritty. Read it even if you say you don’t like fantasy. Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan: At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens and almost accidentally embarks on affairs with an English guy and a Chinese girl. Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners.

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan: At 22, Ava leaves Dublin to teach English as a foreign language to wealthy preteens and almost accidentally embarks on affairs with an English guy and a Chinese girl. Dolan has created a funny, deadpan voice that carries the entire novel. I loved the psychological insight, the playfulness with language, and the zingy one-liners. *A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: Issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance in a perfect-seeming North Carolina community. This is narrated in a first-person plural voice, like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved An American Marriage, it should be next on your list. I’m puzzled by how overlooked it’s been this year.

*A Good Neighborhood by Therese Anne Fowler: Issues of race and privilege undermine a teen romance in a perfect-seeming North Carolina community. This is narrated in a first-person plural voice, like the Greek chorus of a classical tragedy. If you loved An American Marriage, it should be next on your list. I’m puzzled by how overlooked it’s been this year. Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi: A more subdued and subtle book than Homegoing, but its treatment of themes of addiction, grief, racism, and religion is so spot on that it packs a punch. Gifty is a PhD student at Stanford, researching reward circuits in the mouse brain. There’s also a complex mother–daughter relationship and musings on love and risk. [To be published in the UK in March]

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi: A more subdued and subtle book than Homegoing, but its treatment of themes of addiction, grief, racism, and religion is so spot on that it packs a punch. Gifty is a PhD student at Stanford, researching reward circuits in the mouse brain. There’s also a complex mother–daughter relationship and musings on love and risk. [To be published in the UK in March] The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave: A rich, natural exploration of a place and time period – full of detail but wearing its research lightly. Inspired by a real-life storm that struck on Christmas Eve 1617 and wiped out the male population of the Norwegian island of Vardø, it intimately portrays the lives of the women left behind. Tender, surprising, and harrowing.

The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave: A rich, natural exploration of a place and time period – full of detail but wearing its research lightly. Inspired by a real-life storm that struck on Christmas Eve 1617 and wiped out the male population of the Norwegian island of Vardø, it intimately portrays the lives of the women left behind. Tender, surprising, and harrowing. Sisters by Daisy Johnson: Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. For much of this short novel, Johnson keeps readers guessing as to why the girls’ mother, Sheela, took them away to Settle House, her late husband’s family home in the North York Moors. As mesmerizing as it is unsettling.

Sisters by Daisy Johnson: Teenagers September and July were born just 10 months apart, with July always in thrall to her older sister. For much of this short novel, Johnson keeps readers guessing as to why the girls’ mother, Sheela, took them away to Settle House, her late husband’s family home in the North York Moors. As mesmerizing as it is unsettling. The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd: Kidd’s bold fourth novel started as a what-if question: What if Jesus had a wife? Although this retells biblical events, it is chiefly an attempt to illuminate women’s lives in the 1st century and to chart the female contribution to sacred literature and spirituality. An engrossing story of women’s intuition and yearning.

The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd: Kidd’s bold fourth novel started as a what-if question: What if Jesus had a wife? Although this retells biblical events, it is chiefly an attempt to illuminate women’s lives in the 1st century and to chart the female contribution to sacred literature and spirituality. An engrossing story of women’s intuition and yearning. *The Ninth Child by Sally Magnusson: Intense and convincing, this balances historical realism and magical elements. In mid-1850s Scotland, there is a move to ensure clean water. The Glasgow waterworks’ physician’s wife meets a strange minister who died in 1692. A rollicking read with medical elements and a novel look into Victorian women’s lives.

*The Ninth Child by Sally Magnusson: Intense and convincing, this balances historical realism and magical elements. In mid-1850s Scotland, there is a move to ensure clean water. The Glasgow waterworks’ physician’s wife meets a strange minister who died in 1692. A rollicking read with medical elements and a novel look into Victorian women’s lives. *The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting: In this first book of a magic-fueled historical trilogy, progress, religion, and superstition are forces fighting for the soul of a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian village. Mytting constructs the novel around compelling dichotomies. Astrid, a feminist ahead of her time, vows to protect the ancestral church bells.

*The Bell in the Lake by Lars Mytting: In this first book of a magic-fueled historical trilogy, progress, religion, and superstition are forces fighting for the soul of a late-nineteenth-century Norwegian village. Mytting constructs the novel around compelling dichotomies. Astrid, a feminist ahead of her time, vows to protect the ancestral church bells. What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is called upon to help a terminally ill friend commit suicide. The voice is not solely or even primarily the narrator’s but Other: art consumed and people encountered become part of her own story; curiosity about other lives fuels empathy. A quiet novel that sneaks up to seize you by the heartstrings.

What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez: The narrator is called upon to help a terminally ill friend commit suicide. The voice is not solely or even primarily the narrator’s but Other: art consumed and people encountered become part of her own story; curiosity about other lives fuels empathy. A quiet novel that sneaks up to seize you by the heartstrings. Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, written in an aphoristic style. Set either side of Trump’s election in 2016, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are dead right. This felt like a perfect book for 2020 and its worries.

Weather by Jenny Offill: A blunt, unromanticized, wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, written in an aphoristic style. Set either side of Trump’s election in 2016, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom. Offill’s observations are dead right. This felt like a perfect book for 2020 and its worries. Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward: An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. I was particularly taken by the chapter narrated by the ant. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one.

Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward: An intriguing set of linked short stories that combine philosophy and science fiction. Rachel and Eliza are preparing to have a baby together when an ant crawls into Rachel’s eye and she falls ill. I was particularly taken by the chapter narrated by the ant. It’s well worth making a rare dip into sci-fi for this one. *The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Against a backdrop of flooding and bush fires, a series of personal catastrophes play out. A timely, quietly forceful story of how women cope with concrete and existential threats.

*The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts: The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Against a backdrop of flooding and bush fires, a series of personal catastrophes play out. A timely, quietly forceful story of how women cope with concrete and existential threats. To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss: These 10 stories from the last 18 years are melancholy and complex, often featuring several layers of Jewish family history. Europe, Israel, and film are frequent points of reference. “Future Emergencies,” though set just after 9/11, ended up feeling the most contemporary because it involves gas masks and other disaster preparations.

To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss: These 10 stories from the last 18 years are melancholy and complex, often featuring several layers of Jewish family history. Europe, Israel, and film are frequent points of reference. “Future Emergencies,” though set just after 9/11, ended up feeling the most contemporary because it involves gas masks and other disaster preparations. *Help Yourself by Curtis Sittenfeld: A bonus second UK release from Sittenfeld in 2020 after Rodham. Just three stories, but not leftovers; a strong follow-up to You Think It, I’ll Say It. They share the theme of figuring out who you really are versus what others think of you. “White Women LOL,” especially, compares favorably to Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age.

*Help Yourself by Curtis Sittenfeld: A bonus second UK release from Sittenfeld in 2020 after Rodham. Just three stories, but not leftovers; a strong follow-up to You Think It, I’ll Say It. They share the theme of figuring out who you really are versus what others think of you. “White Women LOL,” especially, compares favorably to Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age. You Will Never Be Forgotten by Mary South: In this debut collection, characters turn to technology to stake a claim on originality, compensate for losses, and leave a legacy. These 10 quirky, humorous stories never strayed so far into science fiction as to alienate me. I loved the medical themes and subtle, incisive observations about a technology-obsessed culture.

You Will Never Be Forgotten by Mary South: In this debut collection, characters turn to technology to stake a claim on originality, compensate for losses, and leave a legacy. These 10 quirky, humorous stories never strayed so far into science fiction as to alienate me. I loved the medical themes and subtle, incisive observations about a technology-obsessed culture. *Survival Is a Style by Christian Wiman: Wiman examines Christian faith in the shadow of cancer. This is the third of his books that I’ve read, and I’m consistently impressed by how he makes room for doubt, bitterness, and irony – yet a flame of faith remains. There is really interesting phrasing and vocabulary in this volume.

*Survival Is a Style by Christian Wiman: Wiman examines Christian faith in the shadow of cancer. This is the third of his books that I’ve read, and I’m consistently impressed by how he makes room for doubt, bitterness, and irony – yet a flame of faith remains. There is really interesting phrasing and vocabulary in this volume. Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho: Cho experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She alternates between her time in the mental hospital and her life before the breakdown, weaving in family history and Korean sayings and legends. It’s a painstakingly vivid account.

Inferno: A Memoir by Catherine Cho: Cho experienced stress-induced postpartum psychosis after the birth of her son. She alternates between her time in the mental hospital and her life before the breakdown, weaving in family history and Korean sayings and legends. It’s a painstakingly vivid account. *The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: DNA tests can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction.

*The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are by Libby Copeland: DNA tests can find missing relatives within days. But there are troubling aspects to this new industry, including privacy concerns, notions of racial identity, and criminal databases. A thought-provoking book with all the verve and suspense of fiction. *Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes: Fabes is an emergency room doctor in London and spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents. This warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of his travels achieves a perfect balance between world events, everyday discomforts, and humanitarian volunteering.

*Signs of Life: To the Ends of the Earth with a Doctor by Stephen Fabes: Fabes is an emergency room doctor in London and spent six years of the past decade cycling six continents. This warm-hearted and laugh-out-loud funny account of his travels achieves a perfect balance between world events, everyday discomforts, and humanitarian volunteering. Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: Nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, but Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming in lots of information yet never losing sight of the big picture.

Losing Eden: Why Our Minds Need the Wild by Lucy Jones: Nature’s positive effect on human mental health is something we know intuitively and can explain anecdotally, but Jones wanted to investigate the scientific mechanism behind it. Losing Eden is full of common sense and passion, cramming in lots of information yet never losing sight of the big picture. *Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb: Jewish grandmothers are renowned for their fiercely protective love, but also for nagging. Both sides of the stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny, heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother. A real delight.

*Nobody Will Tell You This But Me: A True (As Told to Me) Story by Bess Kalb: Jewish grandmothers are renowned for their fiercely protective love, but also for nagging. Both sides of the stereotypical matriarch are on display in this funny, heartfelt family memoir, narrated in the second person – as if from beyond the grave – by her late grandmother. A real delight. Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is a leader in the UK’s youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year and the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism.

Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty: McAnulty is a leader in the UK’s youth environmental movement and an impassioned speaker on the love of nature. This is a wonderfully observant and introspective account of his fifteenth year and the joys of everyday encounters with wildlife. Impressive perspective and lyricism. Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey: Trethewey grew up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, then moved with her mother to Atlanta. Her stepfather was abusive; her mother’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to their Memorial Drive apartment after 30 years had passed. A striking memoir, delicate and painful.

Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey: Trethewey grew up biracial in 1960s Mississippi, then moved with her mother to Atlanta. Her stepfather was abusive; her mother’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to their Memorial Drive apartment after 30 years had passed. A striking memoir, delicate and painful.

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey [Nov. 5, Gallic / Oct. 27, Riverhead] “A beautiful and haunting imagining of the years Geppetto spends within the belly of a sea beast. Drawing upon the Pinocchio story while creating something entirely his own, Carey tells an unforgettable tale of fatherly love and loss, pride and regret, and of the sustaining power of art and imagination.” His

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.”

Dearly: New Poems by Margaret Atwood [Nov. 10, Chatto & Windus / Ecco / McClelland & Stewart] “By turns moving, playful and wise, the poems … are about absences and endings, ageing and retrospection, but also about gifts and renewals. They explore bodies and minds in transition … Werewolves, sirens and dreams make their appearance, as do various forms of animal life and fragments of our damaged environment.” Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially

Bright Precious Thing: A Memoir by Gail Caldwell [July 7, Random House] “In a voice as candid as it is evocative, Gail Caldwell traces a path from her west Texas girlhood through her emergence as a young daredevil, then as a feminist.” I’ve enjoyed two of Caldwell’s previous books, especially  The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.”

The Fragments of My Father by Sam Mills [July 9, Fourth Estate] A memoir of being the primary caregiver for her father, who had schizophrenia; with references to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Leonard Woolf, who also found themselves caring for people struggling with mental illness. “A powerful and poignant memoir about parents and children, freedom and responsibility, madness and creativity and what it means to be a carer.” Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.”

Avoid the Day: A New Nonfiction in Two Movements by Jay Kirk [July 28, Harper Perennial] Transylvania, Béla Bartók’s folk songs, an eco-tourist cruise in the Arctic … “Avoid the Day is part detective story, part memoir, and part meditation on the meaning of life—all told with a dark pulse of existential horror.” It was Helen Macdonald’s testimonial that drew me to this: it “truly seems to me to push nonfiction memoir as far as it can go.” World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover?

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil [Aug. 3, Milkweed Editions] “From beloved, award-winning poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil comes a debut work of nonfiction—a collection of essays about the natural world, and the way its inhabitants can teach, support, and inspire us. … Even in the strange and the unlovely, Nezhukumatathil finds beauty and kinship.” Who could resist that title or cover? Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.”

Antlers of Water: Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland, edited by Kathleen Jamie [Aug. 6, Canongate] Contributors include Amy Liptrot, musician Karine Polwart and Malachy Tallack. “Featuring prose, poetry and photography, this inspiring collection takes us from walking to wild swimming, from red deer to pigeons and wasps, from remote islands to back gardens … writing which is by turns celebratory, radical and political.” The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from

The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric [Aug. 27, W.H. Allen] “Drawing on radical solutions from around the world, Krznaric celebrates the innovators who are reinventing democracy, culture and economics so that we all have the chance to become good ancestors and create a better tomorrow.” I’ve been reading a fair bit around this topic. I got a sneak preview of this one from  Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating.

Eat the Buddha: The Story of Modern Tibet through the People of One Town by Barbara Demick [Sept. 3, Granta / July 28, Random House] “Illuminating a culture that has long been romanticized by Westerners as deeply spiritual and peaceful, Demick reveals what it is really like to be a Tibetan in the twenty-first century, trying to preserve one’s culture, faith, and language.” I read her book on North Korea and found it eye-opening. I’ve read a few books about Tibet over the years; it is fascinating. Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake [Sept. 3, Bodley Head / May 12, Random House] “Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into this hidden kingdom of life, and shows that fungi are key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways we think, feel and behave.” I like spotting fungi. Yes, yes, the title and cover are amazing, but also the author’s name!! – how could you not want to read this?

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake [Sept. 3, Bodley Head / May 12, Random House] “Entangled Life is a mind-altering journey into this hidden kingdom of life, and shows that fungi are key to understanding the planet on which we live, and the ways we think, feel and behave.” I like spotting fungi. Yes, yes, the title and cover are amazing, but also the author’s name!! – how could you not want to read this? Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take.

Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson [Sept. 3, Granta] “Woolfson considers prehistoric human‒animal interaction and traces the millennia-long evolution of conceptions of the soul and conscience in relation to the animal kingdom, and the consequences of our belief in human superiority.” I’ve read two previous nature books by Woolfson and have done some recent reading around deep time concepts. This is sure to be a thoughtful and nuanced take. The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary by Melissa Harrison [Nov. 5, Faber & Faber] “Moving from scrappy city verges to ancient, rural Suffolk, where Harrison eventually relocates, this diary—compiled from her beloved “Nature Notebook” column in The Times—maps her joyful engagement with the natural world and demonstrates how we must first learn to see, and then act to preserve, the beauty we have on our doorsteps.” I love seeing her nature finds on Twitter. I think her writing will suit this format.

The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary by Melissa Harrison [Nov. 5, Faber & Faber] “Moving from scrappy city verges to ancient, rural Suffolk, where Harrison eventually relocates, this diary—compiled from her beloved “Nature Notebook” column in The Times—maps her joyful engagement with the natural world and demonstrates how we must first learn to see, and then act to preserve, the beauty we have on our doorsteps.” I love seeing her nature finds on Twitter. I think her writing will suit this format. Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic by David Quammen: This is top-notch scientific journalism: pacey, well-structured, and gripping. The best chapters are on Ebola and SARS; the SARS chapter, in particular, reads like a film screenplay, if this were a far superior version of Contagion. It’s a sobering subject, with some quite alarming anecdotes and statistics, but this is not scare-mongering for the sake of it; Quammen is frank about the fact that we’re still all more likely to get heart disease or be in a fatal car crash.

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

Infinite Home by Kathleen Alcott: “Edith is a widowed landlady who rents apartments in her Brooklyn brownstone to an unlikely collection of humans, all deeply in need of shelter.” (I haven’t read it, but I do have a copy; now would seem like the time to read it!)

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

I love the sound of A Journey Around My Room by Xavier de Maistre: “Finding himself locked in his room for six weeks, a young officer journeys around his room in his imagination, using the various objects it contains as inspiration for a delightful parody of contemporary travel writing and an exercise in Sternean picaresque.”

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

Sourdough by Robin Sloan: Lois Clary, a Bay Area robot programmer, becomes obsessed with baking. “I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.” She attempts to link her job and her hobby by teaching a robot arm to knead the bread she makes for a farmer’s market. Madcap adventures ensue. It’s a funny and original novel and it makes you think, too – particularly about the extent to which we should allow technology to take over our food production.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

The Egg & I by Betty Macdonald: MacDonald and her husband started a rural Washington State chicken farm in the 1940s. Her account of her failure to become the perfect farm wife is hilarious. The voice reminded me of Doreen Tovey’s: mild exasperation at the drama caused by household animals, neighbors, and inanimate objects. “I really tried to like chickens. But I couldn’t get close to the hen either physically or spiritually, and by the end of the second spring I hated everything about the chicken but the egg.” Perfect pre-Easter reading.

Anything by Bill Bryson

Anything by Bill Bryson

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott