Advent Reading: In the Bleak Midwinter by Rachel Mann & More

Today marks 189 years since poet Christina Rossetti’s birth in 1830. You could hardly find better reading for Advent than poet–priest Rachel Mann’s new seasonal devotional, In the Bleak Midwinter, which journeys through Advent and the 12 days of Christmas via short essays on about 40 Rossetti poems.

If your mental picture of Rossetti’s work is, like mine was, limited to twee repetition (“Snow had fallen, snow on snow, / Snow on snow,” as the title carol from 1872 goes), you’ll gain a new appreciation after reading this. Yes, Rossetti’s poetry may strike today’s readers as sentimental, with a bit too much rhyming and overt religion, but it is important to understand it as a product of the Victorian era.

If your mental picture of Rossetti’s work is, like mine was, limited to twee repetition (“Snow had fallen, snow on snow, / Snow on snow,” as the title carol from 1872 goes), you’ll gain a new appreciation after reading this. Yes, Rossetti’s poetry may strike today’s readers as sentimental, with a bit too much rhyming and overt religion, but it is important to understand it as a product of the Victorian era.

Mann gives equal focus to Rossetti’s techniques and themes. Repetition is indeed one of her main tools, used “to build intensity and rhythm,” and some of her poems are psalm-like in their diction and emotion. I had no idea that Rossetti had written so much – and so much that’s specific to the Christmas season. She has multiple poems entitled “Advent” and “A Christmas Carol” (the technical title of “In the Bleak Midwinter”) or variations thereon.

The book’s commentary spins out the many potential metaphorical connotations of Advent: anticipation, hope, suffering, beginnings versus endings. Mann notes that Rossetti often linked Advent and apocalypse as times of change and preparation. Even as Christians await the birth of Christ, the poet seems to say, they should keep the end of all things in mind. Thus, some of the poems include surprisingly dark or premonitory language:

The days are evil looking back,

The coming days are dim;

Yet count we not His promise slack,

But watch and wait for Him. (from “Advent,” 1858)

Death is better far than birth,

You shall turn again to earth. (from “For Advent”)

Along with that note of memento mori, Mann suggests other hidden elements of Rossetti’s poetry, like desire (as in the sensual vocabulary of “Goblin Market”) and teasing mystery (“Winter: My Secret,” which reminded me of Emily Dickinson). Not all of her work is devotional or sweet; those who feel overwhelmed or depressed at Christmastime will also find lines that resonate for them here.

Along with that note of memento mori, Mann suggests other hidden elements of Rossetti’s poetry, like desire (as in the sensual vocabulary of “Goblin Market”) and teasing mystery (“Winter: My Secret,” which reminded me of Emily Dickinson). Not all of her work is devotional or sweet; those who feel overwhelmed or depressed at Christmastime will also find lines that resonate for them here.

Mann helped me to notice Rossetti’s sense of “divine time” that moves in cycles. She also makes a strong case for reading Rossetti to understand how we envision Christmas even now: “In some ways, ‘In the Bleak Midwinter’ offers the acme of our European cultural representations of this season.”

My rating:

With thanks to Canterbury Press for the free copy for review.

(I also reviewed Mann’s poetry collection, A Kingdom of Love, earlier in the year.)

For December I’m reading Do Nothing, the Advent booklet Stephen Cottrell (now the Bishop of Chelmsford; formerly Bishop of Reading) wrote in 2008 about a minimalist, low-stress approach to the holidays. I have to say, it’s inspiring me to cut way back on card-sending and gift-giving this year.

For December I’m reading Do Nothing, the Advent booklet Stephen Cottrell (now the Bishop of Chelmsford; formerly Bishop of Reading) wrote in 2008 about a minimalist, low-stress approach to the holidays. I have to say, it’s inspiring me to cut way back on card-sending and gift-giving this year.

A few seasonal snippets spotted in my recent reading:

“December darkens and darkens, and the streets sprout forth their Christmas tinsel, and the Salvation Army brass band sings hymns and jingles its bells and stirs up its cauldron of money, and loneliness blows in the snowflurries”

(from The Robber Bride by Margaret Atwood)

“Fine old Christmas, with the snowy hair and ruddy face, had done his duty that year in the noblest fashion, and had set off his rich gifts of warmth and colour with all the heightening contrast of frost and snow.”

(from The Mill on the Floss by George Eliot)

A week to Christmas, cards of snow and holly,

Gimcracks in the shops,

Wishes and memories wrapped in tissue paper,

Trinkets, gadgets and lollipops

And as if through coloured glasses

We remember our childhood’s thrill

… And the feeling that Christmas Day

Was a coral island in time where we land and eat our lotus

But where we can never stay.

(from Autumn Journal by Louis MacNeice)

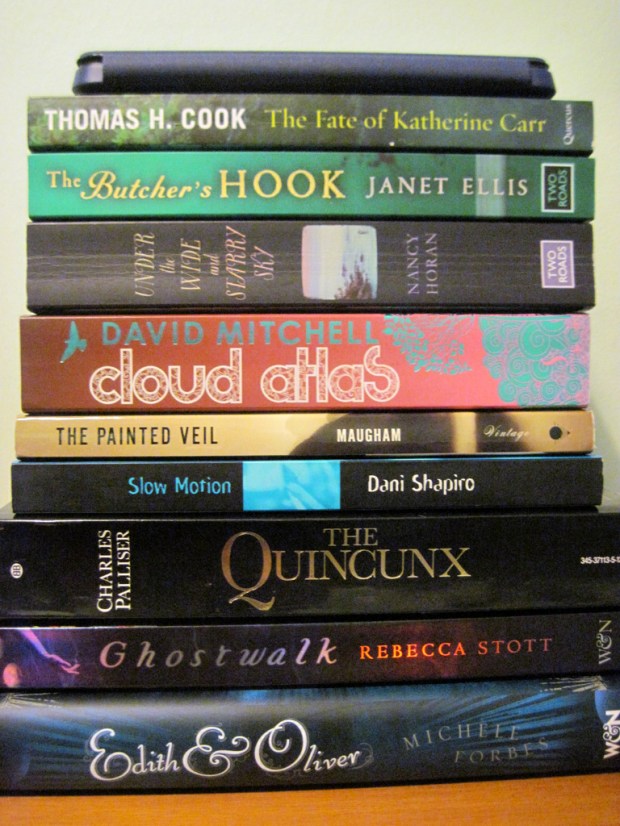

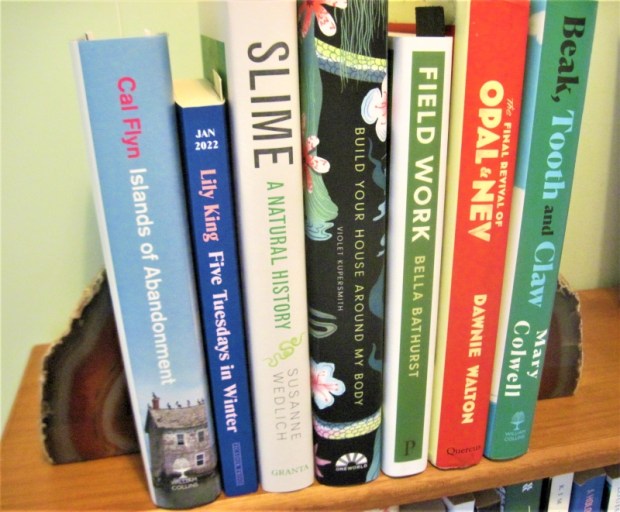

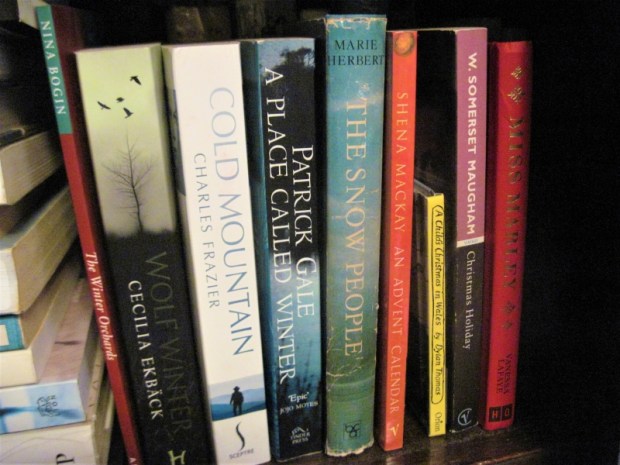

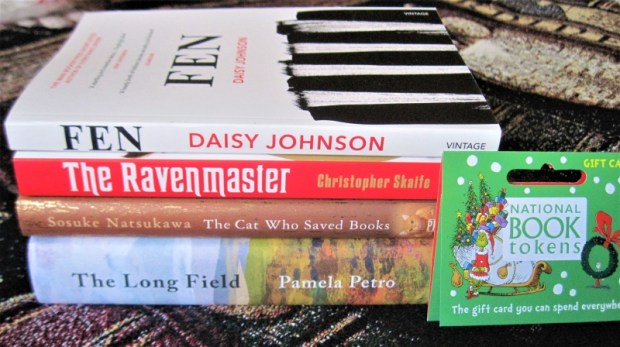

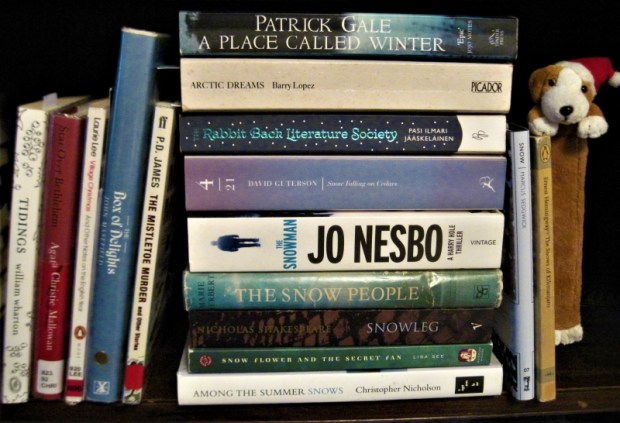

I’m always on the lookout for books that seem to fit the season. Here are the piles I’ve amassed for winter (Early Riser imagines a human hibernation system for the winters), Christmas and snow. I’ll dip into these over the next couple of months. I plan to get more “winter,” “snow” and “ice” titles out from the library. Plus I have this review book (at left), newly in paperback, to start soon.

I’m always on the lookout for books that seem to fit the season. Here are the piles I’ve amassed for winter (Early Riser imagines a human hibernation system for the winters), Christmas and snow. I’ll dip into these over the next couple of months. I plan to get more “winter,” “snow” and “ice” titles out from the library. Plus I have this review book (at left), newly in paperback, to start soon.

Have you read any Advent or wintry books recently?

Snow-y Reads

It’s been a frigid start to March here in Europe. Even though it only amounted to a few inches in total, this is still the most snow we’ve seen in years. We were without heating for 46 hours during the coldest couple of days due to an inaccessible frozen pipe, so I’m grateful that things have now thawed and spring is looking more likely. During winter’s last gasp, though, I’ve been dipping into a few appropriately snow-themed books. I had more success with some than with others. I’ll start with the one that stood out.

Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow by Peter Høeg (1992)

[trans. from the Danish by Felicity David]

Nordic noir avant la lettre? I bought this rather by accident; had I realized it was a murder mystery, I never would have taken a chance on this international bestseller. That would have been too bad, as it’s much more interesting than your average crime thriller. The narrator/detective is Smilla Jaspersen: a 37-year-old mathematician and former Arctic navigator with a Danish father and Greenlander mother, she’s a stylish dresser and a shrewd, bold questioner who makes herself unpopular by nosing about where she doesn’t belong.

Nordic noir avant la lettre? I bought this rather by accident; had I realized it was a murder mystery, I never would have taken a chance on this international bestseller. That would have been too bad, as it’s much more interesting than your average crime thriller. The narrator/detective is Smilla Jaspersen: a 37-year-old mathematician and former Arctic navigator with a Danish father and Greenlander mother, she’s a stylish dresser and a shrewd, bold questioner who makes herself unpopular by nosing about where she doesn’t belong.

Isaiah, a little Greenlander boy, has fallen to his death from the roof of the Copenhagen apartment complex where Smilla also lives, and she’s convinced foul play was involved. In Part I she enlists the help of a mechanic neighbor (and love interest), a translator, an Arctic medicine specialist, and a mining corporation secretary to investigate Isaiah’s father’s death on a 1991 Arctic expedition and how it might be connected to Isaiah’s murder. In Part II she tests her theories by setting sail on the Greenland-bound Kronos as a stewardess. At every turn her snooping puts her in danger – there are some pretty violent scenes.

I read this fairly slowly, over the course of a month (alongside lots of other books); it’s absorbing but in a literary style, so not as pacey or full of cliffhangers as you’d expect from a suspense novel. I got myself confused over all the minor characters and the revelations about the expeditions, so made pencil notes inside the front cover to keep things straight. Setting aside the plot, which gets a bit silly towards the end, I valued this most for Smilla’s self-knowledge and insights into what it’s like to be a Greenlander in Denmark. I read this straight after Gretel Ehrlich’s travel book about Greenland, This Cold Heaven – an excellent pairing I’d recommend to anyone who wants to spend time vicariously traveling in the far north.

Favorite wintry passage:

“I’m not perfect. I think more highly of snow and ice than of love. It’s easier for me to be interested in mathematics than to have affection for my fellow human beings.”

My rating:

One that I left unfinished:

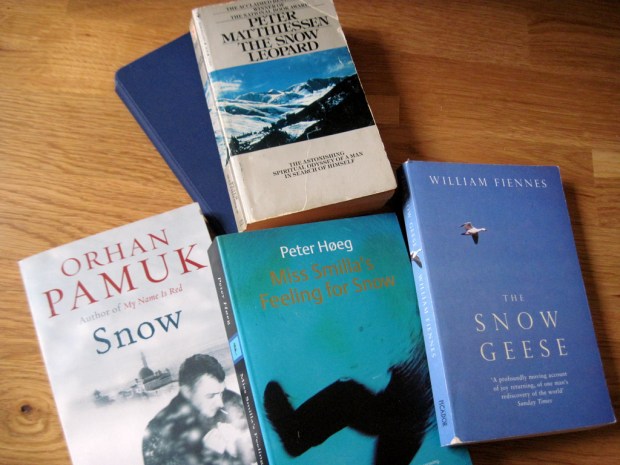

Snow by Orhan Pamuk (2002)

[trans. from the Turkish by Maureen Freely]

This novel seems to be based around an elaborate play on words: it’s set in Kars, a Turkish town where the protagonist, a poet known by the initials Ka, becomes stranded by the snow (Kar in Turkish). After 12 years in political exile in Germany, Ka is back in Turkey for his mother’s funeral. While he’s here, he decides to investigate a recent spate of female suicides, keep tabs on the upcoming election, and see if he can win the love of divorcée Ipek, daughter of the owner of the Snow Palace Hotel, where he’s staying. There’s a hint of magic realism to the novel: the newspaper covers Ka’s reading of a poem called “Snow” before he’s even written it. He and Ipek witness the shooting of the director of the Institute of Education. The attempted assassination is revenge for him banning girls who wear headscarves from schools.

This novel seems to be based around an elaborate play on words: it’s set in Kars, a Turkish town where the protagonist, a poet known by the initials Ka, becomes stranded by the snow (Kar in Turkish). After 12 years in political exile in Germany, Ka is back in Turkey for his mother’s funeral. While he’s here, he decides to investigate a recent spate of female suicides, keep tabs on the upcoming election, and see if he can win the love of divorcée Ipek, daughter of the owner of the Snow Palace Hotel, where he’s staying. There’s a hint of magic realism to the novel: the newspaper covers Ka’s reading of a poem called “Snow” before he’s even written it. He and Ipek witness the shooting of the director of the Institute of Education. The attempted assassination is revenge for him banning girls who wear headscarves from schools.

As in Elif Shafak’s Three Daughters of Eve, the emphasis is on Turkey’s split personality: a choice between fundamentalism (= East, poverty) and secularism (= West, wealth). Pamuk is pretty heavy-handed with these rival ideologies and with the symbolism of the snow. By the time I reached page 165, having skimmed maybe two chapters’ worth along the way, I couldn’t bear to keep going. However, if I get a recommendation of a shorter and subtler Pamuk novel I would give him another try. I did enjoy the various nice quotes about snow (reminiscent of Joyce’s “The Dead”) – it really was atmospheric for this time of year.

Favorite wintry passage:

“That’s why snow drew people together. It was as if snow cast a veil over hatreds, greed and wrath and made everyone feel close to one another.”

My rating:

One that I only skimmed:

The Snow Geese by William Fiennes (2002)

Having recovered from an illness that hit at age 25 while he was studying for a doctorate, Fiennes set off to track the migration route of the snow goose, which starts in the Gulf of Mexico and goes to the Arctic territories of Canada. He was inspired by his father’s love of birdwatching and Paul Gallico’s The Snow Goose (which I haven’t read). I thought this couldn’t fail to be great, what with its themes of travel, birds, illness and identity. However, Fiennes gets bogged down in details. When he stays with friendly Americans in Texas he gives you every detail of their home décor, meals and way of speaking; when he takes a Greyhound bus ride he recounts every conversation he had with his random seatmates. This is too much about the grind of travel and not enough about the natural spectacles he was searching for. And then when he gets up to the far north he eats snow goose. So I ended up just skimming this one for the birdwatching bits. I did like Fiennes’s writing, just not what he chose to focus on, so I’ll read his other memoir, The Music Room.

Having recovered from an illness that hit at age 25 while he was studying for a doctorate, Fiennes set off to track the migration route of the snow goose, which starts in the Gulf of Mexico and goes to the Arctic territories of Canada. He was inspired by his father’s love of birdwatching and Paul Gallico’s The Snow Goose (which I haven’t read). I thought this couldn’t fail to be great, what with its themes of travel, birds, illness and identity. However, Fiennes gets bogged down in details. When he stays with friendly Americans in Texas he gives you every detail of their home décor, meals and way of speaking; when he takes a Greyhound bus ride he recounts every conversation he had with his random seatmates. This is too much about the grind of travel and not enough about the natural spectacles he was searching for. And then when he gets up to the far north he eats snow goose. So I ended up just skimming this one for the birdwatching bits. I did like Fiennes’s writing, just not what he chose to focus on, so I’ll read his other memoir, The Music Room.

My rating:

Considered but quickly abandoned: In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

Considered but quickly abandoned: In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

Would like to read soon: The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen – my husband recently rated this 5 stars and calls it a spiritual quest memoir, with elements of nature and travel writing.

What’s been your snowbound reading this year?

December Reading Plans & Year-End Goals

Somehow the end of the year is less than four weeks away, so it’s time to start getting realistic about what I can read before 2018 begins. I wish I was the sort of person who was always reading books 4+ months before the release date and setting trends, but I’ve only read three 2018 releases so far, and it’s doubtful I’ll get to more than another handful before the end of the year. Any that I do read and can recommend I will round up briefly in a couple weeks or so.

I’m at least feeling pleased with myself for resuming and/or finishing all but two of the 14 books I had on hold as of last month; one I finally DNFed (The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen) and another I’m happy to put off until the new year (Paradise Road: Jack Kerouac’s Lost Highway and My Search for America by Jay Atkinson – since he’s recreating the journey taken for On the Road, I should look over a copy of that first). Ideally, the plan is to finish all the books I’m currently reading to clear the decks for a new year.

Some other vague reading plans for the month:

I might do a Classic of the Month (I’m currently reading The Awakening by Kate Chopin) … but a Doorstopper isn’t looking likely unless I pick up Hillary Clinton’s Living History. However, there are a few books of doorstopper length pictured in the piles below.

Christmas-themed books. The title-less book with the ribbon is Seven Days of Us by Francesca Hornak, a Goodreads giveaway win. I think I’ll start that plus the Amory today since I’m going to a carol service this evening. On Kindle: A Very Russian Christmas, a story anthology I read about half of last year and might finish this year.

Winter-themed books. On Kindle: currently reading When the Professor Got Stuck in the Snow by Dan Rhodes; Winter by Karl Ove Knausgaard is to be read. (The subtitle of Spufford’s book is “Ice and the English Imagination”.)

As the holidays approach, I start to daydream about what books I might indulge in during the time off. (I’m giving myself 11 whole days off of editing, though I may still have a few paid reviews to squeeze in.) The kinds of books I would like to prioritize are:

Absorbing reads. Books that promise to be thrilling (says the person who doesn’t generally read crime thrillers); books I can get lost in (often long ones). On Kindle: The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden.

Cozy reads. Animal books, especially cat books, generally fall into this category, as do funny books and children’s books. My mother and I love Braun’s cat mysteries; I read them all starting when I was about 11. I’ve never reread any, so I’d like to see how they stand up years later. Goodreads has been trying to recommend me Duncton Wood for ages, which is funny as I’ve had my eye on it anyway. My husband read the series when he was a kid and we still own some well-worn copies. Given how much I loved Watership Down and Brian Jacques’ novels as a child, I’m hoping it’s a pretty safe bet.

Books I’ve been meaning to read for ages. ’Nuff said. On Kindle: far too many.

And, as always, I’m in the position of wishing I’d gotten to many more of this year’s releases. In fact, there are at least 22 books from 2017 on my e-readers that I still intend to read:

- A Precautionary Tale: How One Small Town Banned Pesticides, Preserved Its Food Heritage, and Inspired a Movement by Philip Ackerman-Leist

- In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

The Floating World by C. Morgan Babst

The Floating World by C. Morgan Babst- The Day that Went Missing by Richard Beard

- The Best American Series taster volume (skim only?)

- The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne*

- Guesswork: A Memoir in Essays by Martha Cooley

- The Night Brother by Rosie Garland

- Difficult Women by Roxane Gay

- The Twelve-Mile Straight by Eleanor Henderson

- Eco-Dementia by Janet Kauffman [poetry]

- The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy

- A Stitch of Time: The Year a Brain Injury Changed My Language and Life by Lauren Marks

- Hug Everyone You Know: A Year of Community, Courage, and Cancer by Antoinette Truglio Martin

Homing Instinct: Early Motherhood on a Midwestern Farm by Sarah Menkedick

Homing Instinct: Early Motherhood on a Midwestern Farm by Sarah Menkedick- One Station Away by Olaf Olafsson

- Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone by Richard Lloyd Parry

- Memory’s Last Breath: Field Notes on My Dementia by Gerda Saunders

- See What I Have Done by Sarah Schmidt

- What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories by Laura Shapiro

- Midnight at the Bright Ideas Bookstore by Matthew J. Sullivan

- Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward*

* = The two I most want to read, and thus will try hardest to get to before the end of the year. But the Boyne sure is long.

[The 2017 book I most wanted to read but never got hold of in any form was The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas.]

Are there any books from my stacks or lists that you want to put in a good word for?

How does December’s reading look for you?

More Seasonal Reading

I like this reading with the seasons lark. It’s a shame that my library hold on Ali Smith’s Autumn didn’t come in until well after it turned to winter here in England, but I was intrigued by the sound of her post-Brexit seasonal quartet. Then, as if one winter anthology wasn’t enough, I tried another – this time a broader range of literature, history and travel writing.

Autumn by Ali Smith

Smith is attempting a sort of state-of-the-nation novel in four parts. Her two main characters are Daniel Gluck, a centenarian dying at a care home, and his former next-door neighbor, Elisabeth Demand, in her early thirties and still figuring out her path in life. The present world Elisabeth and her mother navigate is a true-to-life post-Brexit bureaucratic nightmare where people are building walls and hurling racist epithets – “news right now is like a flock of speeded-up sheep running off the side of a cliff.” Mostly the book is composed of flashbacks to wordplay-filled conversations between Elisabeth and Daniel when he used to babysit for her, as well as dreams/hallucinations Daniel is having on his deathbed. But there’s also a lot of seemingly irrelevant material about pop artist Pauline Boty and Christine Keeler.

Smith is attempting a sort of state-of-the-nation novel in four parts. Her two main characters are Daniel Gluck, a centenarian dying at a care home, and his former next-door neighbor, Elisabeth Demand, in her early thirties and still figuring out her path in life. The present world Elisabeth and her mother navigate is a true-to-life post-Brexit bureaucratic nightmare where people are building walls and hurling racist epithets – “news right now is like a flock of speeded-up sheep running off the side of a cliff.” Mostly the book is composed of flashbacks to wordplay-filled conversations between Elisabeth and Daniel when he used to babysit for her, as well as dreams/hallucinations Daniel is having on his deathbed. But there’s also a lot of seemingly irrelevant material about pop artist Pauline Boty and Christine Keeler.

This was most likely written very quickly in response to current events, and while some of Smith’s strengths benefit from immediacy – the nearly stream-of-consciousness style (no speech marks) and the jokey dialogue – I think I would have preferred a more circumspect, compressed narrative. In places this was too repetitive, and the seasonal theme felt neither here nor there. I’ll listen out for what the other books are like, but doubt I’ll bother reading them. Aspects of this are very similar to Number 11 by Jonathan Coe (the state-of-Britain remit, even the single mother hoping to appear on a reality show), but I much preferred his take. [Gorgeous cover, though – David Hockney’s Early November Tunnel (2006).]

My rating:

[For more positive reviews, see those by Eric of Lonesome Reader, and Lucy of Hard Book Habit.]

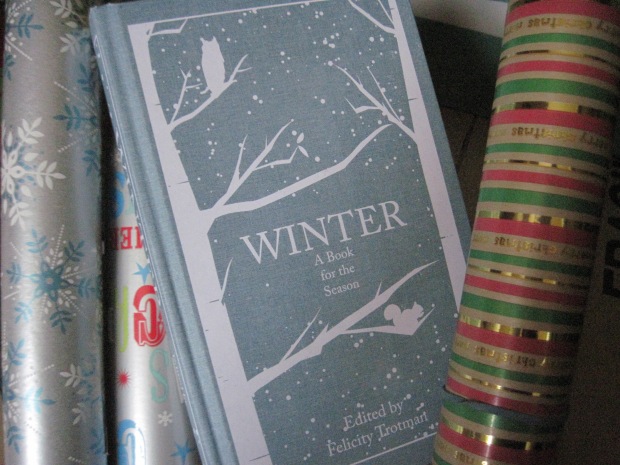

Winter: A Book for the Season, edited by Felicity Trotman

This seasonal anthology contains a nice mixture of poetry, nature and travel pieces, and excerpts from longer works of fiction. Some favorite pieces were W.H. Hudson on the town birds of Bath in the late nineteenth century, Mark Twain on his determination to keep wearing his trademark white through the winter, a Hans Christian Andersen dialogue between a snowman who longs to be by the stove and the yard-dog that warns him away, and Richard Jefferies on those who go out to work on a winter morning. But I enjoyed the poetry the most. Trotman includes a wide range of celebrated poets, from Shakespeare and Keats to John Clare and Wordsworth. I particularly liked a more recent contribution from Carolyn King, “First Snow,” in which a cat imagines that a giant wallpaper stripper has produced the flakes.

This seasonal anthology contains a nice mixture of poetry, nature and travel pieces, and excerpts from longer works of fiction. Some favorite pieces were W.H. Hudson on the town birds of Bath in the late nineteenth century, Mark Twain on his determination to keep wearing his trademark white through the winter, a Hans Christian Andersen dialogue between a snowman who longs to be by the stove and the yard-dog that warns him away, and Richard Jefferies on those who go out to work on a winter morning. But I enjoyed the poetry the most. Trotman includes a wide range of celebrated poets, from Shakespeare and Keats to John Clare and Wordsworth. I particularly liked a more recent contribution from Carolyn King, “First Snow,” in which a cat imagines that a giant wallpaper stripper has produced the flakes.

All told, though, there are too many seventeenth-century and older pieces with archaic spellings, and a number of the history and travel extracts, in particular, feel overlong – with nearly 40 pages in total from Ernest Shackleton’s South. Especially given the thin pages and small type, this represents a tediously large chunk of the book. Shorter pieces increase the variety in an anthology and mean the book lends itself to being picked up and read a few stories at a time. This is one to keep on the coffee table each winter and dip into over several years rather than read straight through. (See my full review at The Bookbag.)

My rating:

As it happens, I’ve now read five books titled Winter: besides the Wildlife Trusts anthology and the novel about Thomas Hardy, both of which I’ve already reviewed here, there’s also Rick Bass’s wonderful memoir of his first year in Montana and Adam Gopnik’s wide-ranging book about the season. But beyond those with the simple one-word title, there are a whole host of titles on my TBR containing the word “Winter”. Here’s the whole list!

Aiken’s books were not part of my childhood, but I was vaguely aware of this first book in a long series when I plucked it from a neighbor’s giveaway pile. The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. In this alternative version of the 1830s, Britain already had an extensive railway network and wolves regularly used the Channel Tunnel (which did not actually open until 1994) to escape the Continent’s brutal winters for somewhat milder climes.

Aiken’s books were not part of my childhood, but I was vaguely aware of this first book in a long series when I plucked it from a neighbor’s giveaway pile. The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. In this alternative version of the 1830s, Britain already had an extensive railway network and wolves regularly used the Channel Tunnel (which did not actually open until 1994) to escape the Continent’s brutal winters for somewhat milder climes. My first 5-star read of the year! It certainly took a while, but I’m now on a roll with a bunch of 4.5- and 5-star ratings bunching together. I remember the buzz surrounding this novel, mostly because of the Ethan Hawke film version that came out when I was a teenager. Even though I didn’t see it, I was aware of it, as I was of other literary fiction that got turned into Oscar-worthy films at about that time, like The Shipping News and House of Sand and Fog.

My first 5-star read of the year! It certainly took a while, but I’m now on a roll with a bunch of 4.5- and 5-star ratings bunching together. I remember the buzz surrounding this novel, mostly because of the Ethan Hawke film version that came out when I was a teenager. Even though I didn’t see it, I was aware of it, as I was of other literary fiction that got turned into Oscar-worthy films at about that time, like The Shipping News and House of Sand and Fog.

Ten-year-old Ruby and her mother Yasmin have arrived in Alaska to visit Ruby’s dad, Matt, who makes nature documentaries. When they arrive, police inform them that the town where he was living has been destroyed by fire and he is presumed dead. But Yasmin won’t believe it and they set out on a 500-mile journey north to find her husband, first hitching a ride with a trucker and then going it alone in a stolen vehicle. All the time, with the weather increasingly brutal, they’re aware of someone following them – someone with malicious intent.

Ten-year-old Ruby and her mother Yasmin have arrived in Alaska to visit Ruby’s dad, Matt, who makes nature documentaries. When they arrive, police inform them that the town where he was living has been destroyed by fire and he is presumed dead. But Yasmin won’t believe it and they set out on a 500-mile journey north to find her husband, first hitching a ride with a trucker and then going it alone in a stolen vehicle. All the time, with the weather increasingly brutal, they’re aware of someone following them – someone with malicious intent.

This was my first time trying the late Lopez. It was supposed to be a buddy read with my husband because we ended up with two free copies, but he raced ahead while I limped along just a few pages at a time before admitting defeat and skimming to the end (it was the 20 pages on musk oxen that really did me in). For me, the reading experience was most akin to

This was my first time trying the late Lopez. It was supposed to be a buddy read with my husband because we ended up with two free copies, but he raced ahead while I limped along just a few pages at a time before admitting defeat and skimming to the end (it was the 20 pages on musk oxen that really did me in). For me, the reading experience was most akin to

During a laughably basic New Testament class in college, a friend and I passed endless notes back and forth, discussing everything but the Bible. I found these the last time I was back in the States going through boxes. My friend’s methodical cursive looked so much more grown-up than my off-topic scrawls. Though she was only two years older, I saw her as a kind of mentor, and when she told me the gist of this Hemingway story I took heed. We must have been comparing our writing ambitions, and I confessed a lack of belief in my ability. She summed up the point of this story more eloquently than Hem himself: if you waited until you were ready to write something perfectly, you’d never write it at all. Well, 19 years later and I’m still held back by lack of confidence, but I have, finally, read the story itself. It’s about a writer on safari in Africa who realizes he is going to die of this gangrene in his leg.

During a laughably basic New Testament class in college, a friend and I passed endless notes back and forth, discussing everything but the Bible. I found these the last time I was back in the States going through boxes. My friend’s methodical cursive looked so much more grown-up than my off-topic scrawls. Though she was only two years older, I saw her as a kind of mentor, and when she told me the gist of this Hemingway story I took heed. We must have been comparing our writing ambitions, and I confessed a lack of belief in my ability. She summed up the point of this story more eloquently than Hem himself: if you waited until you were ready to write something perfectly, you’d never write it at all. Well, 19 years later and I’m still held back by lack of confidence, but I have, finally, read the story itself. It’s about a writer on safari in Africa who realizes he is going to die of this gangrene in his leg. I couldn’t resist the title and creepy Magritte cover, so added this to my basket during the Waterstones online sale at the start of the year. Liardet’s name was unfamiliar to me, though this was the Bath University professor’s tenth poetry collection. Most of the unusual titles begin with “Self-Portrait” – for instance, “Self-Portrait as the Nashua Girl’s Reverse Nostalgia” and “Self-Portrait with Blind-Hounding Viewed in Panoramic Lens.” Apparently there is a throughline here, but if it weren’t for the blurb I would have missed it entirely. (“During a record-breaking blizzard in Boston, two poets met, one American and one English. This meeting marked the beginning of a life-transforming love affair.”) There were some turns of phrase and alliteration I liked, but overall I preferred the few poems that were not part of that pretentious central plot, e.g. “Ommerike” (part I) about mysterious mass deaths of birds and fish, “Nonagenaria,” a portrait of an old woman, and “The Guam Fever,” voiced by an ill soldier.

I couldn’t resist the title and creepy Magritte cover, so added this to my basket during the Waterstones online sale at the start of the year. Liardet’s name was unfamiliar to me, though this was the Bath University professor’s tenth poetry collection. Most of the unusual titles begin with “Self-Portrait” – for instance, “Self-Portrait as the Nashua Girl’s Reverse Nostalgia” and “Self-Portrait with Blind-Hounding Viewed in Panoramic Lens.” Apparently there is a throughline here, but if it weren’t for the blurb I would have missed it entirely. (“During a record-breaking blizzard in Boston, two poets met, one American and one English. This meeting marked the beginning of a life-transforming love affair.”) There were some turns of phrase and alliteration I liked, but overall I preferred the few poems that were not part of that pretentious central plot, e.g. “Ommerike” (part I) about mysterious mass deaths of birds and fish, “Nonagenaria,” a portrait of an old woman, and “The Guam Fever,” voiced by an ill soldier.

I’d only seen covers with a rabbit and top hat, so was confused that the secondhand copy I ordered with a birthday voucher featured a lit-up farmhouse set back into snowy woods. The first third of the novel takes place in Los Angeles, where Sabine lived with her husband Parsifal, the magician she assisted for 20 years, but the rest is set in winter-encased Nebraska. The contrast between the locations forms a perfect framework for a story of illusions versus reality.

I’d only seen covers with a rabbit and top hat, so was confused that the secondhand copy I ordered with a birthday voucher featured a lit-up farmhouse set back into snowy woods. The first third of the novel takes place in Los Angeles, where Sabine lived with her husband Parsifal, the magician she assisted for 20 years, but the rest is set in winter-encased Nebraska. The contrast between the locations forms a perfect framework for a story of illusions versus reality. This Little Toller book is, at just over 100 pages, the perfect read for a wintry afternoon. It’s a lot like

This Little Toller book is, at just over 100 pages, the perfect read for a wintry afternoon. It’s a lot like  A taut early novella (just 110 pages) set in an Australian valley called the Sink. Animals have been disappearing: a pet dog snatched from its chain; livestock disemboweled. Four locals are drawn together by fear of an unidentified killer. Maurice Stubbs is the only one given a first-person voice, but passages alternate between his perspective and those of his wife Ida, Murray Jaccob, and Veronica, a pregnant teen. These are people on the edge, reckless and haunted by the past. The malevolent force comes to take on a vengeful nature. I was reminded of Andrew Michael Hurley’s novels. My first taste of Winton’s fiction has whetted my appetite to read more by him – I have Cloudstreet on the shelf.

A taut early novella (just 110 pages) set in an Australian valley called the Sink. Animals have been disappearing: a pet dog snatched from its chain; livestock disemboweled. Four locals are drawn together by fear of an unidentified killer. Maurice Stubbs is the only one given a first-person voice, but passages alternate between his perspective and those of his wife Ida, Murray Jaccob, and Veronica, a pregnant teen. These are people on the edge, reckless and haunted by the past. The malevolent force comes to take on a vengeful nature. I was reminded of Andrew Michael Hurley’s novels. My first taste of Winton’s fiction has whetted my appetite to read more by him – I have Cloudstreet on the shelf.

Many of these 30 short stories originally appeared in publications like the Scotsman, Tablet and Glasgow Herald between the 1940s and 1990s, with some also reprinted in previous Mackay Brown story volumes. This posthumous collection of seasonal tales by Orkney’s best-known writer runs the gamut from historical fiction to timeless fable, and travels from the Holy Land to Scotland’s islands. Often, Orkney is contrasted with Edinburgh, as in one of my favorites, “A Christmas Exile,” in which a boy is sent off to Granny’s house in Orkney one winter while his mother is in hospital and longs to make it home in time for Christmas.

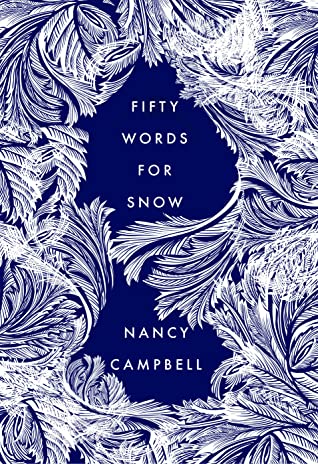

Many of these 30 short stories originally appeared in publications like the Scotsman, Tablet and Glasgow Herald between the 1940s and 1990s, with some also reprinted in previous Mackay Brown story volumes. This posthumous collection of seasonal tales by Orkney’s best-known writer runs the gamut from historical fiction to timeless fable, and travels from the Holy Land to Scotland’s islands. Often, Orkney is contrasted with Edinburgh, as in one of my favorites, “A Christmas Exile,” in which a boy is sent off to Granny’s house in Orkney one winter while his mother is in hospital and longs to make it home in time for Christmas. Words for snow exist in most of the world’s languages – even those spoken in countries where it rarely, if ever, snows. For instance, Thai has “hima” at the ready even though there were only once claims of a snow flurry in Thailand, in 1955. Campbell meanders through history, legend, and science in these one- to five-page essays. I was most taken by the pieces on German “kunstschnee” (the fake snow used on movie sets), Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” (snowflakes big as a dog’s paw, a phrase used as a track title on one of Jónsi’s albums – an excuse for discussing the amazing Sigur Rós), and Estonian “jäätee” (the terrifying ice road that runs between the mainland and the island of Hiiumaa – only when the ice is 22 cm thick, and with cars traveling 2 minutes apart and maintaining a speed of 25–40 km/hour).

Words for snow exist in most of the world’s languages – even those spoken in countries where it rarely, if ever, snows. For instance, Thai has “hima” at the ready even though there were only once claims of a snow flurry in Thailand, in 1955. Campbell meanders through history, legend, and science in these one- to five-page essays. I was most taken by the pieces on German “kunstschnee” (the fake snow used on movie sets), Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” (snowflakes big as a dog’s paw, a phrase used as a track title on one of Jónsi’s albums – an excuse for discussing the amazing Sigur Rós), and Estonian “jäätee” (the terrifying ice road that runs between the mainland and the island of Hiiumaa – only when the ice is 22 cm thick, and with cars traveling 2 minutes apart and maintaining a speed of 25–40 km/hour). This

This

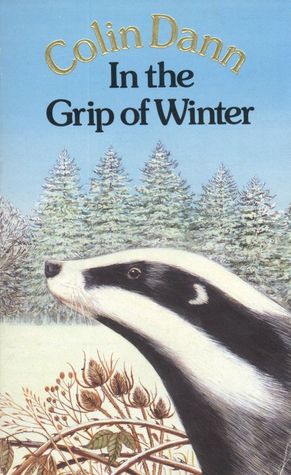

In this second book of the Farthing Wood series, the animals endure a harsh winter in their new home, the White Deer Park. When Badger falls down a slope and injures his leg, he’s nursed back to health at the Warden’s cottage, where Ginger Cat tempts him to join in a life of comfort and plenty. Meanwhile, Fox, Tawny Owl and the others are near starvation, and resort to leaving the park and stealing food from farms and rubbish bins. They have to band together and use their cunning to survive. This was a sweet book that reminded me of my childhood love of anthropomorphized animal stories (like Watership Down and the Redwall series). I doubt I’ll read another from the series, but this was a quaint read for the season.

In this second book of the Farthing Wood series, the animals endure a harsh winter in their new home, the White Deer Park. When Badger falls down a slope and injures his leg, he’s nursed back to health at the Warden’s cottage, where Ginger Cat tempts him to join in a life of comfort and plenty. Meanwhile, Fox, Tawny Owl and the others are near starvation, and resort to leaving the park and stealing food from farms and rubbish bins. They have to band together and use their cunning to survive. This was a sweet book that reminded me of my childhood love of anthropomorphized animal stories (like Watership Down and the Redwall series). I doubt I’ll read another from the series, but this was a quaint read for the season.

Once a year or so I encounter a book that’s so flawlessly written you could pick out just about any sentence and marvel at its construction. That’s certainly the case here. I never want to go to Greenland; English winters are quite dark and cold enough for me, and I don’t know if I could stomach seal meat at all, let alone for most meals and often raw. But that’s okay: I don’t need to book a flight to Qaanaaq, because through reading this I’ve already been in Greenland in every season, and I thoroughly enjoyed my armchair trek. Impressively, Ehrlich is always describing the same sorts of scenery, and yet every time finds a fresh way to write about ice and sun glare and frigid temperatures. I’ll be looking into her other books for sure.

Once a year or so I encounter a book that’s so flawlessly written you could pick out just about any sentence and marvel at its construction. That’s certainly the case here. I never want to go to Greenland; English winters are quite dark and cold enough for me, and I don’t know if I could stomach seal meat at all, let alone for most meals and often raw. But that’s okay: I don’t need to book a flight to Qaanaaq, because through reading this I’ve already been in Greenland in every season, and I thoroughly enjoyed my armchair trek. Impressively, Ehrlich is always describing the same sorts of scenery, and yet every time finds a fresh way to write about ice and sun glare and frigid temperatures. I’ll be looking into her other books for sure. This short novel from 2005 deserves to be better known. It reminded me of

This short novel from 2005 deserves to be better known. It reminded me of  This is my favorite of the three Knausgaard books I’ve read so far, and miles better than his Autumn. These short essays successfully evoke the sensations of winter and the conflicting emotions elicited by family life and childhood memories. The series is, loosely speaking, a set of instruction manuals for his unborn daughter, who is born a month premature in the course of this volume. So in the first book he starts with the basics of bodily existence – orifices, bodily fluids and clothing – and now he’s moving on to slightly more advanced but still everyday things she’ll encounter, like coins, stuffed animals, a messy house, toothbrushes, and the moon. I’ll see out this series, and see afterwards if I have the nerve to return to My Struggle.

This is my favorite of the three Knausgaard books I’ve read so far, and miles better than his Autumn. These short essays successfully evoke the sensations of winter and the conflicting emotions elicited by family life and childhood memories. The series is, loosely speaking, a set of instruction manuals for his unborn daughter, who is born a month premature in the course of this volume. So in the first book he starts with the basics of bodily existence – orifices, bodily fluids and clothing – and now he’s moving on to slightly more advanced but still everyday things she’ll encounter, like coins, stuffed animals, a messy house, toothbrushes, and the moon. I’ll see out this series, and see afterwards if I have the nerve to return to My Struggle. Many poetry volumes get a middling rating from me because some of the poems are memorable but others do nothing for me. This is on the longer side for a collection at 120+ pages, but only a handful of its poems fell flat. The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe (my cover depicts the Avebury stone circle in the gloom), menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. The title poem, which appears first, has a slightly melancholy tone with its focus on the short days of winter, but the poet defiantly asserts meaning despite the mood: “Even the dead of winter: it seethes with more / than I can ever live to name and speak.” Piercy was a great discovery, and I’ll be trying lots more of her books from various genres.

Many poetry volumes get a middling rating from me because some of the poems are memorable but others do nothing for me. This is on the longer side for a collection at 120+ pages, but only a handful of its poems fell flat. The subjects are diverse: travels in Europe (my cover depicts the Avebury stone circle in the gloom), menstruation, identifying as a Jew as well as a feminist, scattering her father’s ashes, the stresses of daily life, and being in love. The title poem, which appears first, has a slightly melancholy tone with its focus on the short days of winter, but the poet defiantly asserts meaning despite the mood: “Even the dead of winter: it seethes with more / than I can ever live to name and speak.” Piercy was a great discovery, and I’ll be trying lots more of her books from various genres.

The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden: Some striking turns of phrase, an enchanting wintry atmosphere … but a little Disney-fied for me. I got this free for Kindle so may come back to it at some point.

The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden: Some striking turns of phrase, an enchanting wintry atmosphere … but a little Disney-fied for me. I got this free for Kindle so may come back to it at some point.