Library Checkout, December 2020

I resumed my twice-weekly library volunteering on the 3rd but had to stop again after the 17th because West Berkshire moved into Tier 4, which means people should stay at home except for essential activities (work and schooling). Who knows when I’ll be able to go back!

I managed to squeeze in a good few 2020 releases before the end of the year. I’ve started amassing a pile of backlist reads, but I’m also placing requests on 2021 releases that the library has on order. The usual limit for reservations is 15, but by commandeering my husband’s unused library card I’ve effectively doubled my allowance. I don’t expect I’ll be able to pick up any more books until this new lockdown is over, though, so I can start off the year by focusing on a neglected pile of university library books and especially my own shelves – always a good thing.

I would be delighted to have other bloggers – and not just book bloggers – join in this meme. Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (on the last Monday of every month), or tag me on Twitter and/or Instagram: @bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout.

I rate most books I read or skim, and include links to reviews not already featured on the blog.

READ

- Mr. Wilder & Me by Jonathan Coe

- Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan

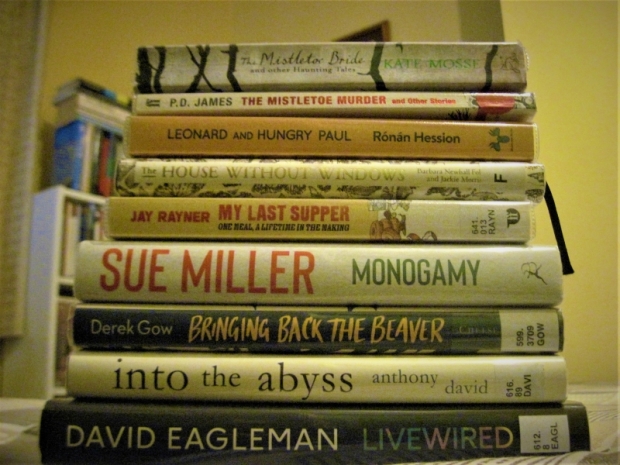

- Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways by Derek Gow

- The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

- Kay’s Anatomy: A Complete (and Completely Disgusting) Guide to the Human Body by Adam Kay

- To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss

- A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth by Daniel Mason

- Monogamy by Sue Miller

- First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger

SKIMMED

- Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain by David Eagleman

- Christmas: A Biography by Judith Flanders

- Growing Goats and Girls: Living the Good Life on a Cornish Farm by Rosanne Hodin

- Village Christmas and Other Notes on the English Year by Laurie Lee

- My Last Supper: One Meal, a Lifetime in the Making by Jay Rayner

- The Invention of Surgery: A History of Modern Medicine: From the Renaissance to the Implant Revolution by David Schneider, MD

CURRENTLY READING

- Leonard and Hungry Paul by Rónán Hession (a buddy read with Annabel)

- The Marriage of Opposites by Alice Hoffman (for January book club)

- The Dickens Boy by Thomas Keneally

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- Hormonal: A Conversation about Women’s Bodies, Mental Health and Why We Need to Be Heard by Eleanor Morgan

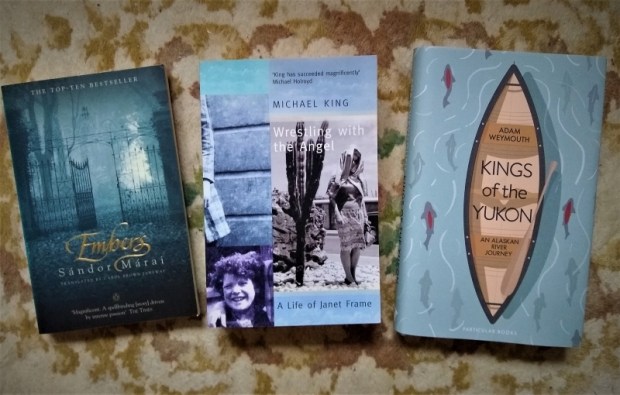

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Mama’s Boy: A Memoir by Dustin Lance Black

- In Our Mad and Furious City by Guy Gunaratne

- Country Doctor: Hilarious True Stories from a Country Practice by Michael Sparrow

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- The Idea of the Brain: A History by Matthew Cobb

- Big Girl, Small Town by Michelle Gallen

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Things I Learned on the 6.28: A Commuter’s Guide to Reading by Stig Abell

- A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion by Fay Bound Alberti

- Can Bears Ski? by Raymond Antrobus

- The Cat and the City by Nick Bradley

- All the Young Men by Ruth Coker Burks

- Breathtaking: Life and Death in a Time of Contagion by Rachel Clarke

- The Living Sea of Waking Dreams by Richard Flanagan

- In the Woods by Tana French

- Begin Again by Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.

- Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden

- Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed by Lori Gottlieb

- The Sealwoman’s Gift by Sally Magnusson

- A Burning by Megha Majumdar

- A Crooked Tree by Una Mannion

- A Promised Land by Barack Obama

- A Fire in My Head (poetry) by Ben Okri

- Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud

- How We Met: A Memoir of Love and Other Misadventures by Huma Qureshi

- My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell

- My US Election Diary by Jon Sopel

- The Mystery of Charles Dickens by A.N. Wilson

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang

RETURNED UNFINISHED

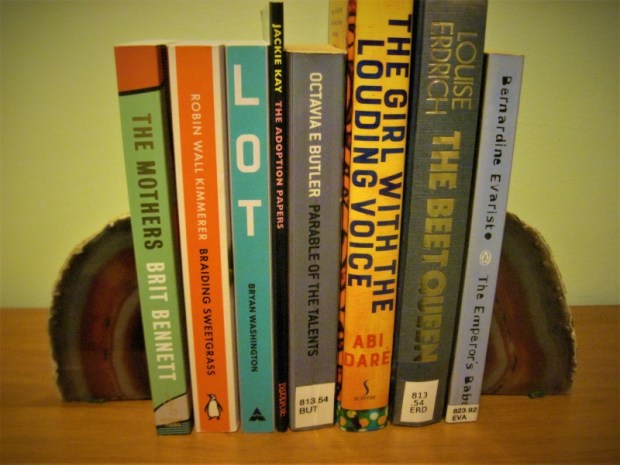

- The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré

RETURNED UNREAD

- Star Over Bethlehem and Other Stories by Agatha Christie

- The Mistletoe Murder and Other Stories by P.D. James

- Manchester Happened by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

- A Box of Delights by John Masefield

- The Mistletoe Bride & Other Haunting Tales by Kate Mosse

(I lost interest in all of these. I don’t gravitate towards crime or short stories, so shouldn’t have been surprised that once I had them in front of me they didn’t appeal. Also, I didn’t realize the Masefield was abridged, and I prefer not to read altered editions.)

What appeals from my stacks?

The Ones that Got Away: DNFs, Most Anticipated Reads & More

Following on from my late June list of DNFs, here are the rest of the books I abandoned this year (asterisks next to the ones I intend to try again someday):

Summer before the Dark: Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth, Ostend 1936 by Volker Weidermann – Too niche.

The Motion of the Body through Space by Lionel Shriver – Too non-PC.

When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir by Patrisse Khan-Cullors – Too been-there.

*The Wild Laughter by Caoilinn Hughes – Too much economics.

Birdsong on Mars by Jon Glover & Two Tongues by Claudine Toutoungi – Carcanet poetry releases. Style/reader mismatch issue for both.

That Reminds Me by Derek Owusu – Too dull.

3 Summers by Lisa Robertson (poetry) – Too weird.

Apeirogon by Colum McCann – Too long.

*We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates – Too much of quirky folks.

Persuasion by Jane Austen – Too much telling.

Golden Boy by Abigail Tarttelin – Too brutal.

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller – Too much Greek myth.

*Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart – Too misery-memoir.

Night-Gaunts and Other Tales of Suspense by Joyce Carol Oates – Maddening punctuation.

The Corset by Laura Purcell – Too lifeless.

True Story by Kate Reed Petty – Too consciously relevant.

As You Were by Elaine Feeney – Too much of mental hospitals.

*House of Glass by Hadley Freeman – Too detailed.

Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent – Too much snowflake woe.

Le Bal by Irène Némirovsky – Too gloomy.

The Wasp Factory by Iain Banks – Too disturbing.

The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré – Too precocious.

Restless by William Boyd – Too ordinary.

No getting around it: I have lots of DNFs. I’ve not done a great job recording them this year, but I think it was 46, which works out to about 12% of the books I’ve started. Most years it’s around 15%, so for me that’s not too bad, but I know some of you never have DNFs, or could count them on one hand. How do you do it? Do you sample books beforehand? Do you make yourself finish everything you start even if you’re not enjoying it? Or are you just that good at picking what will suit your tastes? Sometimes I overestimate my interest in a subject or my tolerance for subpar writing. In recent years my patience for mediocre books has waned, and I’m allergic to some writers’ style for reasons that are often difficult to pinpoint.

In early July, I highlighted the 15 releases from the second half of the year that I was most looking forward to reading. Here’s how I did:

Read: 10 [Slight disappointments (i.e., rated 3 stars): 4]

Languishing on my Kindle, but I still intend to read: 2

Haven’t managed to find yet: 3

Getting to two-thirds of my most anticipated books is really good for me!

I regret not having enough time left in 2020 to finish Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann, especially because Cathy and Susan both named it as one of their favorite books of the year.

I regret not having enough time left in 2020 to finish Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann, especially because Cathy and Susan both named it as one of their favorite books of the year.

The additional 2020 releases I most wished I’d found time for before the end of this year (from my late November list of year-end reading plans) include Marram by Leonie Charlton, D by Michel Faber, and Alone Together: Love, Grief, and Comfort in the Time of COVID-19. This last one was offered to me by the editor on Goodreads and I feel bad for not following through with a review, but somehow the subject feels too close to the bone. Maybe next year?

The additional 2020 releases I most wished I’d found time for before the end of this year (from my late November list of year-end reading plans) include Marram by Leonie Charlton, D by Michel Faber, and Alone Together: Love, Grief, and Comfort in the Time of COVID-19. This last one was offered to me by the editor on Goodreads and I feel bad for not following through with a review, but somehow the subject feels too close to the bone. Maybe next year?

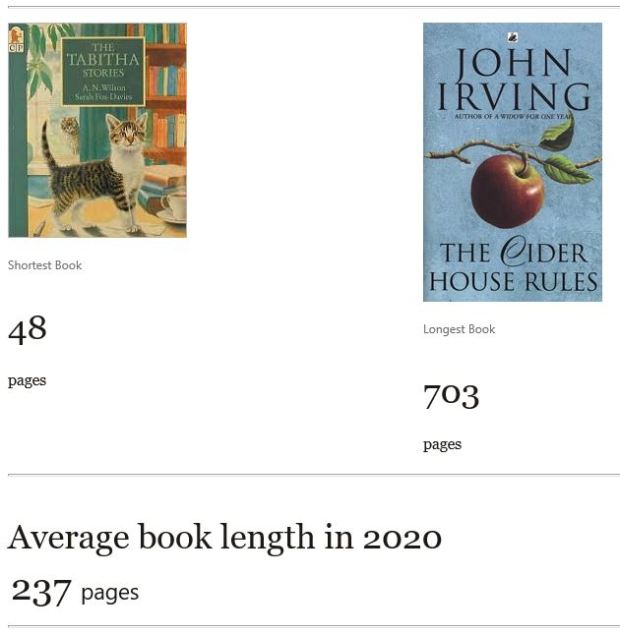

I’ll be back to start the countdown of my favorite books of the year on the 26th, starting with fiction and poetry. On the 27th it’s all about nonfiction. A break for Library Checkout on the 28th, followed by 2020 runners-up on the 29th, best backlist reads on the 30th, and some superlatives and statistics on the 31st.

Merry Christmas!

Mrs. Shields & Me: (Re)reading Carol Shields in 2020

It’s pure happenstance that I started reading Carol Shields’s work in 2006.

2005: When I first returned to England for my MA program at Leeds, I met a PhD student who was writing a dissertation on contemporary Canadian women writers. At that point I could literally name only one – Margaret Atwood – and I hadn’t even read anything by her yet.

2006: Back in the States after that second year abroad, living with my parents and killing time until my wedding, I got an evening job behind the circulation desk of the local community college library. A colleague passed on four books to me one day. By tying them up in a ribbon, she made a gift out of hand-me-downs: The Giant’s House, The Secret History, and two by Shields: Happenstance and The Stone Diaries. I’ve gone on to read most or all of the books by these authors, so I’m grateful to this acquaintance I’ve since lost touch with.

The inspiration for my post title.

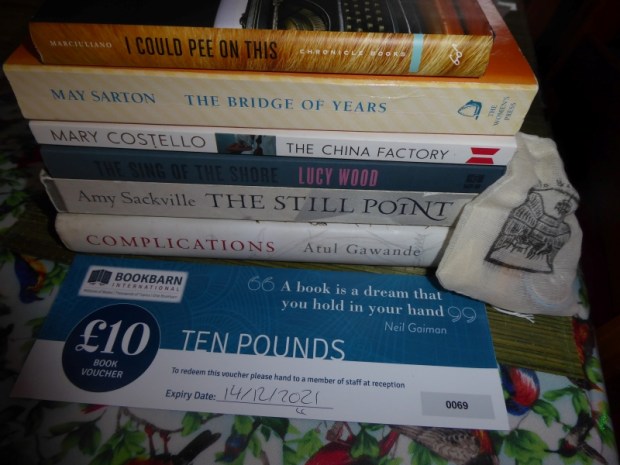

Starting in June this year, I joined Marcie of Buried in Print in reading or rereading six Shields novels. She’s been rereading Shields for many years, and I benefited from her insight and careful attention to connections between the works’ characters and themes during our buddy reads. I’d treated myself to a secondhand book binge in the first lockdown, including copies of three Shields novels I’d not read before. We started with these.

Small Ceremonies (1976)

Shields’s debut ended up being my surprise favorite. A flawless novella, it brings its many elements to a satisfying conclusion and previews the author’s enduring themes in 180 pages. Judith is working on a third biography, of Susanna Moodie, and remembering the recent sabbatical year that she and her husband, a Milton scholar, spent with their two children in Birmingham. High tea is a compensating ritual she imported from a dismal England. She also brought back an idea for a novel. Meanwhile family friend Furlong Eberhardt, author of a string of twee, triumphantly Canadian novels, is casting around for plots.

What ensues is something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Specific links to her later work include a wonderful dinner party scene with people talking over each other and a craft project.

What ensues is something of a sly academic comedy à la David Lodge, laced with Shields’s quiet wisdom on marriage, parenting, the writer’s vocation, and the difficulty of ever fully understanding another life. Specific links to her later work include a wonderful dinner party scene with people talking over each other and a craft project.

The Box Garden (1977)

The companion novel to Small Ceremonies is narrated by Judith’s sister Charleen, a poet and single mother who lives in Vancouver and produces the National Botanical Journal. I imagined the sisters representing two facets of Shields, who had previously published poetry and a Moodie biography. Charleen is preparing to travel to Toronto for their 70-year-old mother’s wedding to Louis, an ex-priest. Via flashbacks and excruciating scenes at the family home, we learn how literally and emotionally stingy their mother has always been. If Charleen’s boyfriend Eugene’s motto is to always assume the best of people, her mother’s modus operandi is to assume she’s been hard done by.

The companion novel to Small Ceremonies is narrated by Judith’s sister Charleen, a poet and single mother who lives in Vancouver and produces the National Botanical Journal. I imagined the sisters representing two facets of Shields, who had previously published poetry and a Moodie biography. Charleen is preparing to travel to Toronto for their 70-year-old mother’s wedding to Louis, an ex-priest. Via flashbacks and excruciating scenes at the family home, we learn how literally and emotionally stingy their mother has always been. If Charleen’s boyfriend Eugene’s motto is to always assume the best of people, her mother’s modus operandi is to assume she’s been hard done by.

The title comes from the time when a faithful Journal correspondent, the mysterious Brother Adam, sent Charleen some grass seed to grow in a window box – a symbol of thriving in spite of restrictive circumstances. I thought the plot went off in a silly direction, but loved the wedding reception. Specific links to Shields’s later work include a botanical hobby, a long train journey, and a final scene delivered entirely in dialogue.

A Celibate Season (1991)

“We’re suffering a communication gap, that’s obvious.”

This epistolary novel was a collaboration: Blanche Howard wrote the letters by Jocelyn (“Jock”), who’s gone to Ottawa to be the legal counsel for a commission looking into women’s poverty, while Shields wrote the replies from her husband Charles (“Chas”), an underemployed architect who’s keeping the home fire burning back in Vancouver. He faces challenges large and small: their daughter’s first period versus meal planning (“Found the lentils. Now what?”). The household starts comically expanding to include a housekeeper, Chas’s mother-in-law, a troubled neighbor, and so on.

This epistolary novel was a collaboration: Blanche Howard wrote the letters by Jocelyn (“Jock”), who’s gone to Ottawa to be the legal counsel for a commission looking into women’s poverty, while Shields wrote the replies from her husband Charles (“Chas”), an underemployed architect who’s keeping the home fire burning back in Vancouver. He faces challenges large and small: their daughter’s first period versus meal planning (“Found the lentils. Now what?”). The household starts comically expanding to include a housekeeper, Chas’s mother-in-law, a troubled neighbor, and so on.

Both partners see how the other half lives. The misunderstandings between them become worse during their separation. Howard and Shields started writing in 1983, and the book does feel dated; they later threw in a jokey reference to the unreliability of e-mail to explain why the couple are sending letters and faxes. Two unsent letters reveal secrets Jock and Chas are keeping from each other, which felt like cheating. I remained unconvinced that so much could change in 10 months, and the weird nicknames were an issue for me. Plus, arguing about a solarium building project? Talk about First World problems! All the same, the letters are amusing.

Rereads

Happenstance (1980/1982)

This was the first novel I read by Shields. My Penguin paperback gives the wife’s story first and then you flip it over to read the husband’s story. But the opposite reflects the actual publishing order: Happenstance is Jack’s story; two years later came Brenda’s story in A Fairly Conventional Woman. The obvious inheritor of the pair is A Celibate Season with the dual male/female narratives, and the setups are indeed similar: a man is left at home alone with his teenage kids, having to cope with chores and an unexpected houseguest.

This was the first novel I read by Shields. My Penguin paperback gives the wife’s story first and then you flip it over to read the husband’s story. But the opposite reflects the actual publishing order: Happenstance is Jack’s story; two years later came Brenda’s story in A Fairly Conventional Woman. The obvious inheritor of the pair is A Celibate Season with the dual male/female narratives, and the setups are indeed similar: a man is left at home alone with his teenage kids, having to cope with chores and an unexpected houseguest.

What I remembered beforehand: The wife goes to a quilting conference; an image of a hotel corridor and elevator.

Happenstance

Jack, a museum curator in Chicago, is writing a book about “Indian” trading practices (this isn’t the word we’d use nowadays, but the terminology ends up being important to the plot). He and his best friend Bernie, who’s going through a separation, are obsessed with questions of history: what gets written down, and what it means to have a sense of the past (or not). I loved all the little threads, like Jack’s father’s obsession with self-help books, memories of Brenda’s vivacious single mother, and their neighbor’s failure as Hamlet in a local production. I also enjoyed an epic trek in the snow in a final section potentially modeled on Ulysses.

A Fairly Conventional Woman

“Aside from quiltmaking, pleasantness was her one talent. … She had come to this awkward age, forty, at an awkward time in history – too soon to be one of the new women, whatever that meant, and too late to be an old-style woman.”

Brenda is in Philadelphia for a quilting conference. Quilting, once just a hobby, is now part of a modern art movement and she earns prizes and hundreds of dollars for her pieces. The hotel is overbooked, overlapping with an International Society of Metallurgists gathering, and both she and Barry from Vancouver, an attractive metallurgist in a pinstriped suit whom she meets in the elevator, are driven from their shared rooms by roommates bringing back one-night stands. This doesn’t add anything to the picture of a marriage in Jack’s story and I only skimmed it this time. It’s a wonder I kept reading Shields after this, but I’m so glad I did!

I reviewed these last two earlier this year. They were previously my joint favorites of Shields’s work, linked by a gardening hobby, the role of chance, and the unreliability of history and (auto)biography. They remain in my top three.

The Stone Diaries (1995)

The Stone Diaries (1995)

What I remembered beforehand: a long train ride, a friend who by the feeling ‘down there’ thought that someone had had sex with her the night before, and something about the Orkney Islands.

Larry’s Party (1997)

Larry’s Party (1997)

What I remembered beforehand: a food poisoning incident (though I’d thought it was in one of Shields’s short stories), a climactic event involving a garden maze, a chapter entitled “Larry’s Penis,” and the closing dinner party scene.

Looking back: Fortunately, in the last 15 years I’ve done something to redress my ignorance, discovering Canadian women writers whom I admire greatly: Elizabeth Hay, Margaret Laurence, Mary Lawson and especially Margaret Atwood and Carol Shields.

Looking out: “I am watching. My own life will never be enough for me. It is a congenital condition, my only, only disease in an otherwise lucky life. I am a watcher, an outsider whether I like it or not, and I’m stuck with the dangers that go along with it. And the rewards.”

- That’s Judith on the last page of Small Ceremonies. It’s also probably Shields. And, to an extent, it seems like me. A writer, but mostly a reader, absorbing other lives.

Looking forward: I’m interested in rereading Shields’s short stories and Mary Swann (to be reissued by World Editions in 2021). And, though I’ve read 13 of her books now, there are still plenty of unread, lesser-known ones I’ll have to try to find secondhand one day. Her close attention to ordinary lives and relationships and the way we connect to the past makes her work essential.

Book Serendipity in the Final Months of 2020

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. (Earlier incidents from the year are here, here, and here.)

- Eel fishing plays a role in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson.

- A girl’s body is found in a canal in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and Carrying Fire and Water by Deirdre Shanahan.

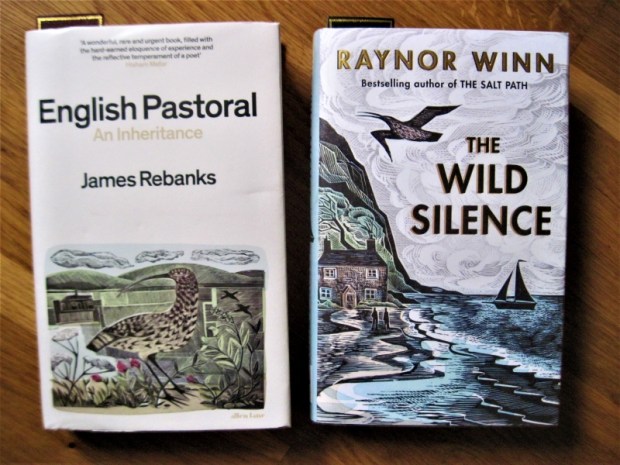

- Curlews on covers by Angela Harding on two of the most anticipated nature books of the year, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn (and both came out on September 3rd).

- Thanksgiving dinner scenes feature in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid.

- A gay couple has the one man’s mother temporarily staying on the couch in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Memorial by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading two “The Gospel of…” titles at once, The Gospel of Eve by Rachel Mann and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson (and I’d read a third earlier in the year, The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving).

- References to Dickens’s David Copperfield in The Cider House Rules by John Irving and Mudbound by Hillary Jordan.

- The main female character has three ex-husbands, and there’s mention of chin-tightening exercises, in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer.

- A Welsh hills setting in On the Red Hill by Mike Parker and Along Came a Llama by Ruth Janette Ruck.

- Rachel Carson and Silent Spring are mentioned in A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee, The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson. SS was also an influence on Losing Eden by Lucy Jones, which I read earlier in the year.

- There’s nude posing for a painter or photographer in The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel, How to Be Both by Ali Smith, and Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- A weird, watery landscape is the setting for The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey and Piranesi by Susanna Clarke.

- Bawdy flirting between a customer and a butcher in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Just Like You by Nick Hornby.

- Corbels (an architectural term) mentioned in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver.

- Near or actual drownings (something I encounter FAR more often in fiction than in real life, just like both parents dying in a car crash) in The Idea of Perfection, The Glass Hotel, The Gospel of Eve, Wakenhyrst, and Love and Other Thought Experiments.

- Nematodes are mentioned in The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A toxic lake features in The New Wilderness by Diane Cook and Real Life by Brandon Taylor (both were also on the Booker Prize shortlist).

- A black scientist from Alabama is the main character in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- Graduate studies in science at the University of Wisconsin, and rivals sabotaging experiments, in Artifact by Arlene Heyman and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A female scientist who experiments on rodents in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Artifact by Arlene Heyman.

- There are poems about blackberrying in Dearly by Margaret Atwood, Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols, and How to wear a skin by Louisa Adjoa Parker. (Nichols’s “Blackberrying Black Woman” actually opens with “Everyone has a blackberry poem. Why not this?” – !)

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Library Checkout, November 2020

Although lockdown precluded me from doing my usual volunteering at the public library this month, it has remained open for collecting reservations, so I was able to pick up another small pile of 2020 titles last week. Meanwhile, I worked my way through a big pile of recent releases that were reserved after me, plus a few novellas. With any luck, I’ll be back to my biweekly volunteering sessions starting on the first Thursday in December. I’ve missed having a reason to leave the house, see people, and find more books at random.

I would be delighted to have other bloggers – and not just book bloggers – join in this meme. Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (on the last Monday of every month), or tag me on Twitter and/or Instagram: @bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout.

I rate most books I read or skim, and include links to reviews not already featured on the blog.

READ

- Surge by Jay Bernard

- Your House Will Pay by Steph Cha

- The Last Runaway by Tracy Chevalier

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Just Like You by Nick Hornby

- Tilly and the Map of Stories (Pages & Co., #3) by Anna James

- Vesper Flights: New and Selected Essays by Helen Macdonald

- The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

- Something Special by Iris Murdoch

- Dear Reader: The Comfort and Joy of Books by Cathy Rentzenbrink

- The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

- Real Life by Brandon Taylor

- The Order of the Day, Éric Vuillard

- Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward

- The Courage to Care: A Call for Compassion by Christie Watson

+ Children’s picture books (don’t worry, these don’t count towards my year’s reading list!)

- Six Dinner Sid: A Highland Adventure by Inga Moore

- Bad Cat! by Nicola O’Byrne

- One Smart Fish by Christopher Wormell

SKIMMED

- The Book of Gutsy Women by Chelsea Clinton and Hillary Rodham Clinton

- Dependency by Tove Ditlevsen

- What Have I Done? An Honest Memoir about Surviving Postnatal Mental Illness by Laura Dockrill

- Untamed: Stop Pleasing, Start Living by Glennon Doyle

- Mantel Pieces: Royal Bodies and Other Writing from the London Review of Books by Hilary Mantel

- Duty of Care: One NHS Doctor’s Story of Courage and Compassion on the COVID-19 Frontline by Dr Dominic Pimenta

CURRENTLY READING

- The Girl with the Louding Voice by Abi Daré

- The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

- A Registry of My Passage upon the Earth by Daniel Mason

- First Time Ever: A Memoir by Peggy Seeger

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- Kay’s Anatomy: A Complete (and Completely Disgusting) Guide to the Human Body by Adam Kay

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- The Marriage of Opposites by Alice Hoffman (for January book club)

- The Dickens Boy by Thomas Keneally

- To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss

- Growing Goats and Girls: Living the Good Life on a Cornish Farm by Rosanne Hodin

+ A small Christmas-themed stack I’ve set aside to peruse next month.

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Mr Wilder & Me by Jonathan Coe

- My Last Supper: One Meal, a Lifetime in the Making by Jay Rayner

- The Invention of Surgery: A History of Modern Medicine: From the Renaissance to the Implant Revolution by David Schneider, MD

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- The Idea of the Brain: A History by Matthew Cobb

- Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan

- Livewired: The Inside Story of the Ever-Changing Brain by David Eagleman

- Maybe You Should Talk to Someone: A Therapist, Her Therapist, and Our Lives Revealed by Lori Gottlieb

- Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways by Derek Gow

- Leonard and Hungry Paul by Rónán Hession

- Manchester Happened by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

- Monogamy by Sue Miller

- Hormonal: A Conversation about Women’s Bodies, Mental Health and Why We Need to Be Heard by Eleanor Morgan

- A Promised Land by Barack Obama

- Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud

- The Mystery of Charles Dickens by A.N. Wilson

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney – I read the first chapter. I think I’ve simply had too many quirky narrators and/or mental hospital stories recently.

- House of Glass: The Story and Secrets of a Twentieth-Century Jewish Family by Hadley Freeman – I read to page 30 but, as with The Yellow House by Sarah Broom, I realized there is far more detail in this family memoir than I am able to absorb. And here, the writing is only average. It reminded me of Esther Safran Foer’s memoir.

- Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent – I didn’t enjoy the style of the first few pages, so didn’t want to commit to another 300+ about a twentysomething’s job, housing, and relationship woes.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Travels in the Scriptorium by Paul Auster – I couldn’t fit this in for Novellas for November. Maybe another year.

- Kill My Mother: A Graphic Novel by Jules Feiffer – I couldn’t stand the drawing style.

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson – After a skim back through Gilead, I felt I knew enough about Jack and didn’t need yet another sequel.

What appeals from my stacks?

Thinking Realistically about Reading Plans for the Rest of the Year

The other year I did something dangerous: I started an exclusive Goodreads shelf (i.e., an option besides the standard “Read,” “Currently Reading” and “Want to Read”) called “Set Aside Temporarily,” where I stick a book I have to put on hiatus for whatever reason, whether I’d read 20 pages or 200+. This enabled me to continue in my bad habit of leaving part-read books lying around. I know I’m unusual for taking multi-reading to an extreme with 20‒30 books on the go at a time. For the most part, this works for me, but it does mean that less compelling books or ones that don’t have a review deadline attached tend to get ignored.

I swore I’d do away with the Set Aside shelf in 2020, but it hasn’t happened. In fact, I made another cheaty shelf, “Occasional Reading,” for bedside books and volumes I read a few pages in once a week or so (e.g. devotional works on lockdown Sundays), but I don’t perceive this one to be a problem; no matter if what’s on it carries over into 2021.

Looking at the five weeks left in the year and adapting the End of the Year Book Tag Laura did recently, I’ve been thinking about what I can realistically read in 2020.

Is there a book that you started that you still need to finish by the end of the year?

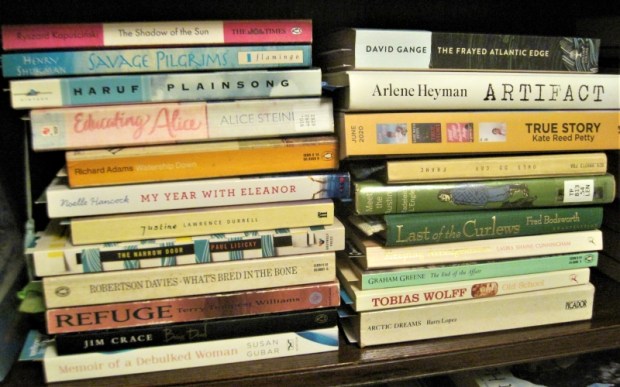

So many! I hope to finish most, if not all, of the books I’m currently reading, plus I’d like to clear these set aside stacks as much as possible. If nothing else, I have to finish the two review books (Gange and Heyman, on the top of the right-hand stack).

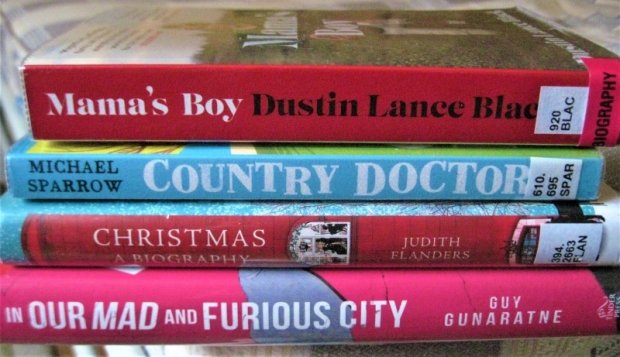

Name some books you want to read by the end of the year.

I still have these four print books to review on the blog. The Shields, a reissue, is for a December blog tour; I might save the snowy one for later in the winter.

I will also be reading an e-copy of Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce for a BookBrowse review.

The 2020 releases I’d placed holds on are still arriving to the library for me. Of them, I’d most like to get to:

The 2020 releases I’d placed holds on are still arriving to the library for me. Of them, I’d most like to get to:

- Mr Wilder & Me by Jonathan Coe

- Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways by Derek Gow

- To Be a Man by Nicole Krauss

My Kindle is littered with 2020 releases I purchased or downloaded from NetGalley and intended to get to this year, including buzzy books like My Dark Vanessa. I don’t read so much on my e-readers anymore, but I’ll see if I can squeeze in one or two of these:

Fat by Hanne Blank

Fat by Hanne Blank- Marram by Leonie Charlton

- D by Michel Faber

- Alone Together: Love, Grief, and Comfort in the Time of COVID-19, edited by Jennifer Haupt

- Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann

- Avoid the Day by Jay Kirk*

- World of Wonders by Aimee Nezhukumatathil*

*These were on my Most Anticipated list for the second half of 2020.

The Nezhukumatathil would also count towards the #DiverseDecember challenge Naomi F. is hosting. I assembled this set of potentials: four books that I own and am eager to read on the left, and four books from libraries on the right.

Is there a book that could still shock you and become your favorite of the year?

Two books I didn’t finish until earlier this month, The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel and Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald, leapt into contention for first place for the year in fiction and nonfiction, respectively, and it’s entirely possible that something I’ve got out from the library or on my Kindle (as listed above) could be just as successful. That’s why I wait until the last week of the year to finalize Best Of lists.

Do you have any books that are partly read and languishing? How do you decide on year-end reading priorities?

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.  The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.  I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread. The facts are these. Daisy’s mother, Mercy, dies giving birth to her in rural Manitoba. Raised by a neighbor, Daisy later moves to Indiana with her stonecutter father, Cuyler. After a disastrously short first marriage, Daisy returns to Canada to marry Barker Flett. Their three children and Ottawa garden become her life. She temporarily finds purpose in her empty-nest years by writing a “Mrs. Green Thumb” column for a local newspaper, but her retirement in Florida is plagued by illness and the feeling that she has missed out on what matters most.

The facts are these. Daisy’s mother, Mercy, dies giving birth to her in rural Manitoba. Raised by a neighbor, Daisy later moves to Indiana with her stonecutter father, Cuyler. After a disastrously short first marriage, Daisy returns to Canada to marry Barker Flett. Their three children and Ottawa garden become her life. She temporarily finds purpose in her empty-nest years by writing a “Mrs. Green Thumb” column for a local newspaper, but her retirement in Florida is plagued by illness and the feeling that she has missed out on what matters most. As in Moon Tiger, one of my absolute favorites, the author explores how events and memories turn into artifacts. The meta approach also, I suspect, tips the hat to other works of Canadian literature: in her introduction, Margaret Atwood mentions that the poet whose story inspired Shields’s Mary Swann had a collection entitled A Stone Diary, and surely the title’s similarity to Margaret Laurence’s

As in Moon Tiger, one of my absolute favorites, the author explores how events and memories turn into artifacts. The meta approach also, I suspect, tips the hat to other works of Canadian literature: in her introduction, Margaret Atwood mentions that the poet whose story inspired Shields’s Mary Swann had a collection entitled A Stone Diary, and surely the title’s similarity to Margaret Laurence’s