A May Sarton Birthday Celebration

These days I consider May Sarton one of my favourite authors, but I’ve only been reading her for about nine years, since I picked up Journal of a Solitude on a whim. (Ten years prior, when I was a senior in college working in a used bookstore on evenings and weekends, a customer came up and asked me if we had anything by May Sarton. I had never heard of her so said no, only later discovering that we shelved her in with Classic literature. Huh. I can only apologize to that long-ago customer for my ignorance and negligence.)

A general-interest article I wrote on May Sarton’s life and work appears in the May/June 2023 issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I am an associate editor. I submitted this feature back in August 2019, so it’s taken quite some time for it to see the light of day, but I’m pleased that the publication happened to coincide with the anniversary of her birth. In fact, today, May 3rd, would have been her 111th birthday. For the article, I covered a selection of Sarton’s fiction and nonfiction, and gave a brief discussion of her poetry (which the magazine doesn’t otherwise cover).

A general-interest article I wrote on May Sarton’s life and work appears in the May/June 2023 issue of Bookmarks magazine, for which I am an associate editor. I submitted this feature back in August 2019, so it’s taken quite some time for it to see the light of day, but I’m pleased that the publication happened to coincide with the anniversary of her birth. In fact, today, May 3rd, would have been her 111th birthday. For the article, I covered a selection of Sarton’s fiction and nonfiction, and gave a brief discussion of her poetry (which the magazine doesn’t otherwise cover).

The two below, a journal and a novel, are works I’ve read more recently. Both were secondhand purchases, I think from Awesomebooks.com.

Encore: A Journal of the Eightieth Year (1993)

Sarton is one of those reasonably rare authors who published autobiography, fiction AND poetry. I know I’m not alone in thinking that the journals and memoirs are where she really shines. (She herself was proudest of her poetry, and resented the fact that publishers only seemed to be interested in novels because they were what sold.) I came to her through her journals, which she started writing in her sixties, and I love them for how frankly they come to terms with ageing and the ill health and loss it inevitably involves. They are also such good, gentle companions in that they celebrate seasonality and small joys: her beautiful New England homes, her gardening hobby, her pets, and her writing routines and correspondence.

Sarton is one of those reasonably rare authors who published autobiography, fiction AND poetry. I know I’m not alone in thinking that the journals and memoirs are where she really shines. (She herself was proudest of her poetry, and resented the fact that publishers only seemed to be interested in novels because they were what sold.) I came to her through her journals, which she started writing in her sixties, and I love them for how frankly they come to terms with ageing and the ill health and loss it inevitably involves. They are also such good, gentle companions in that they celebrate seasonality and small joys: her beautiful New England homes, her gardening hobby, her pets, and her writing routines and correspondence.

Encore was the only journal I had left unread; soon it will be time to start rereading my top few. When Sarton wrote this in 1991–2, she was recovering from a spell of illness and assumed it would be her final journal. (In fact, At Eighty-Two would appear two years later.) Although she still struggles with pain and low energy, the overall tone is of gratitude and rediscovery of wonder. Whereas a few of the later journals can get a bit miserable because she’s so anxious about her health and the state of the world, here there is more looking back at life’s highlights. Perhaps because Margot Peters was in the process of researching her biography (which would not appear until after her death), she was nudged into the past more often. I especially appreciated a late entry where she lists “peak experiences,” ranging from her teen years to age 80. What a positive way of thinking about one’s life!

For many months I kept this as a bedside book and read just an entry or two a night. When I started reading it more quickly and straight through, I did note some repetition, which Sarton worried would result from her dictating into a recording device. But I don’t think this detracts significantly. In this volume, events of note include a trip to London and commemorative publications plus a conference all to mark her 80th birthday. She’s just as pleased with tiny signs of her success, though, such as a fan letter saying The House by the Sea inspired the reader to put up a bird feeder.

The Education of Harriet Hatfield (1988)

This is my eighth Sarton novel. In general, I’ve had less success with her fiction as it can be formulaic: characters exist to play stereotypical roles and/or serve as mouthpieces for the author’s opinions. That’s certainly true of Harriet Hatfield, who, like the protagonist of Mrs. Stevens Hears the Mermaids Singing, is fairly similar to Sarton. After the death of her long-time partner, Vicky, who ran a small publishing house, sixty-year-old Harriet decides to open a women’s bookstore in a Boston suburb. She has no business acumen, just enthusiasm (and money, via the inheritance from Vicky). College girls, housewives, nuns and older feminists all become regulars, but Hatfield House also attracts unwanted attention in this dodgy neighbourhood, especially after a newspaper outs Harriet: graffiti, petty theft and worse. The police are little help, but Harriet’s brothers and a local gay couple promise to look out for her.

The central struggle for Harriet is whether she will remain a private lesbian – as one customer says to her, “you are old and respectable and no one would ever guess”; that is, she can pass as straight – or become part of a more audible, visible movement toward equal rights. It’s cringe-worthy how unsubtly Sarton has Harriet recognize (the “Education” the title speaks of) her privilege and accept her parity with other minorities through friendships with a Black mother, a battered wife who gets an abortion, and a man whose partner is dying of AIDS. Harriet’s brother, too, comes out to her as gay, and I was uneasy with the portrayal of him and the AIDS patient as promiscuous to the point of bringing any suffering on themselves.

The central struggle for Harriet is whether she will remain a private lesbian – as one customer says to her, “you are old and respectable and no one would ever guess”; that is, she can pass as straight – or become part of a more audible, visible movement toward equal rights. It’s cringe-worthy how unsubtly Sarton has Harriet recognize (the “Education” the title speaks of) her privilege and accept her parity with other minorities through friendships with a Black mother, a battered wife who gets an abortion, and a man whose partner is dying of AIDS. Harriet’s brother, too, comes out to her as gay, and I was uneasy with the portrayal of him and the AIDS patient as promiscuous to the point of bringing any suffering on themselves.

Still, when I consider that Sarton was in her late seventies at the time she was writing this, and that public knowledge of AIDS would have been poor at best, I think this was admirably edgy. Harriet’s dilemma reflects Sarton’s own identity crisis, as expressed in Encore: “I do not wish to be labeled as a lesbian and do not wish to be labeled as a woman writer but consider myself a universal writer who is writing for human beings.” Nowadays, though, what Harriet deems discretion comes across as cowardice and priggishness.

While there are elements of Harriet Hatfield that have not aged well, if you focus on the Bythell-esque bookshop stuff (“I find that the people I love best are those who come in to browse, the silent shy ones, who are hungry for books rather than for conversation”) rather than the consciousness-raising or the mystery subplot, you might enjoy it as much as I did. Kudos for the first and last lines, anyway: “How rarely is it possible for anyone to begin a new life at sixty!” and “It’s the real world and I am fully alive in it.”

The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry (2022)

“What’s lost when your idea of the other dies? He knows the answer: only the entire world.”

Elizabeth Lowry’s utterly immersive third novel, The Chosen, currently on the shortlist for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction*, examines Thomas Hardy’s relationship with his first wife, Emma Gifford. The main storyline is set in November–December 1912 and opens on the morning of Emma’s death at Max Gate, their Dorchester home of 27 years. The couple had long been estranged and effectively lived separate lives on different floors of the house, but instantly Hardy is struck with pangs of grief – and remorse for how he had treated Emma. (He would pour these emotions out into some of his most famous poems.)

That guilt is only compounded by what he finds in her desk: her short memoir, Some Recollections, with an account of their first meeting in Cornwall; and her journals going back two decades, wherein she is brutally honest about her husband’s failings and pretensions. “I expect nothing from him now & that is just as well – neither gratitude nor attention, love, nor justice. He belongs to the public & all my years of devotion count for nothing.” She describes him as little better than a jailor, and blames him for their lifelong childlessness.

It’s an exercise in self-flagellation, yet as weeks crawl by after her funeral, Hardy continues to obsessively read Emma’s “catalogue of her grievances.” In the fog of grief, he relives scenes his late wife documented – especially the composition and controversial publication of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Emma hoped to be his amanuensis and so share in the thrill of creation, but he nipped a potential reunion in the bud. Lowry intercuts these flashbacks with the central narrative in a way that makes Hardy feel like a bumbling old man; he has trouble returning to reality afterwards, and his sisters and the servants are concerned for him.

Hardy was that stereotypical figure: the hapless man who needs women around to do everything for him. Luckily, he’s surrounded by an abundance of strong female characters: his sister Kate, who takes temporary control of the household; his secretary, Florence Dugdale, who had been his platonic companion and before long became his second wife; even Emma’s money-grubbing niece, Lilian, who descends to mine her aunt’s wardrobe.

I particularly enjoyed Hardy’s literary discussions with Edmund Gosse, who urged him to temper the bleakness of his plots, and the stranger-than-fiction incident of a Chinese man visiting Hardy at home and telling him his own story of neglecting his wife and repenting his treatment of her after her death.

For anyone who’s read and loved Hardy’s major works, or visited his homes, this feels absolutely true to his life story, and so evocative of the places involved. I could picture every locale, from Stinsford churchyard to Emma’s attic bedroom. It was perfect reading for my short break in Dorset earlier in the month and brought back memories of the Hardy tourism I did at the end of my study abroad year in 2004. Although Hardy’s written words permeate the book, I was impressed to learn that Lowry invented all of Emma’s journal entries, based on feelings she had expressed in letters.

But there is something universal, of course, about a tale of waning romance, unexpected loss, and regret for all that is left undone. This is such a beautifully understated novel, perfectly convincing for the period but also timeless. It’s one to shelve alongside Winter by Christopher Nicholson, another favourite of mine about Hardy’s later life.

With thanks to riverrun (Quercus) for the free copy for review. The Chosen came out in paperback on 13 April.

*The winner will be announced on 15 June.

Spring Reads, Part I: Violets and Rain

We had both rain and spring sunshine on a recent overnight trip to Bridport, Dorset – a return visit after enjoying it so much in 2019. Several elements were repeated: Dorset Nectar cider farm, dinner at Dorshi, and a bookshop and charity shop crawl of the main streets. While we didn’t revisit Thomas Hardy sites, I spent plenty of time at Max Gate by reading Elizabeth Lowry’s The Chosen. Beach walks plus one in the New Forest on the way back were splendid. This was my haul from Bridport Old Books. Stocking up on novellas and poetry, plus a novel by a Canadian author I’ve enjoyed work from before.

Now for a quick look at two tangentially spring-related books I’ve read recently: a short novel about two women’s wartime experiences of motherhood and an elegiac and allusive poetry collection.

Violets by Alex Hyde (2022)

I was intrigued by the sound of this debut novel, which juxtaposes the lives of two young British women named Violet at the close of the Second World War. One miscarries twins and, told she’ll not be able to bear children, has to rethink her whole future; another sails from Wales to Italy on ATS war service, hiding the fact that she’s pregnant by a departed foreign soldier. Hyde’s spare style – no speech marks; short paragraphs or solitary lines separated by spaces – alternates between their stories in brief numbered chapters, bringing them together in a perhaps predictable way that also forms a reimagining of her father’s life story. The narration at times addresses this future character in poems that I think are supposed to be fond and prophetic but I instead found strangely blunt and even taunting (as in the excerpt below). There’s inadequate time to get to know, or care about, either Violet.

Can you feel it, Pram Boy?

Can you march in time?

A change, a hardening,

the jarring of the solid ground as she treads,

gets her pockets picked.

[…]

Quick! March!

And your Mama, Pram Boy,

yeasty in her private parts.

Granta sent a free copy. Violets came out in paperback in February.

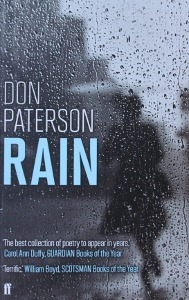

Rain by Don Paterson (Faber, 2009)

I’d previously read Paterson’s 40 Sonnets, in 2015. This collection is in memoriam of the late poet Michael Donaghy, the subject of the late multi-part “Phantom.” There are a couple of poems in Scots and a sequence of seven nature-infused ones designated as being “after” poets from Li Po to Robert Desnos. Several appear to express concern for a son. There’s a haiku-like rhythm to the short stanzas of “Renku: My Last Thirty-Five Deaths.” I didn’t understand why “Unfold i.m. Akira Yoshizawa” was a blank page until I looked him up and learned that he was a famous origamist. The title poem closes the collection:

I’d previously read Paterson’s 40 Sonnets, in 2015. This collection is in memoriam of the late poet Michael Donaghy, the subject of the late multi-part “Phantom.” There are a couple of poems in Scots and a sequence of seven nature-infused ones designated as being “after” poets from Li Po to Robert Desnos. Several appear to express concern for a son. There’s a haiku-like rhythm to the short stanzas of “Renku: My Last Thirty-Five Deaths.” I didn’t understand why “Unfold i.m. Akira Yoshizawa” was a blank page until I looked him up and learned that he was a famous origamist. The title poem closes the collection:

I love all films that start with rain:

rain, braiding a windowpane

or darkening a hung-out dress

or streaming down her upturned face;

one big thundering downpour

right through the empty script and score

before the act, before the blame,

before the lens pulls through the frame

to where the woman sits alone

beside a silent telephone

I liked individual passages or images but didn’t find much of a connecting theme behind Paterson’s disparate interests. (University library)

Another favourite passage:

So I collect the dull things of the day

in which I see some possibility

[…]

I look at them and look at them until

one thing makes a mirror in my eyes

then I paint it with the tear to make it bright.

This is why I sit up through the night.

(from “Why Do You Stay Up So Late?”)

And a DNF:

Corpse Beneath the Crocus by N.N. Nelson – I loved the title and the cover, and a widow’s bereavement memoir in poems seemed right up my street. I wish I’d realized Atmosphere is a vanity press, which would explain why these are among the worst poems I’ve read: cliché-riddled and full of obvious sentiments and metaphors as she explores specific moments but mostly overall emotions. Three excerpts:

Corpse Beneath the Crocus by N.N. Nelson – I loved the title and the cover, and a widow’s bereavement memoir in poems seemed right up my street. I wish I’d realized Atmosphere is a vanity press, which would explain why these are among the worst poems I’ve read: cliché-riddled and full of obvious sentiments and metaphors as she explores specific moments but mostly overall emotions. Three excerpts:

All things die

In the flowering cycle

Of growth and life

Time passes

Like sand in an hourglass

Feelings are changeful

Like the tide

Ebbing and flowing

“Love Letter,” a prose piece, held the most promise, which suggests Nelson would have been better off attempting memoir. I slogged (hate-read, really) my way through to the halfway point but could bear it no longer. (NetGalley)

I have a few more spring-themed books on the go: Hoping for a better set next time!

Any spring reads on your plate?

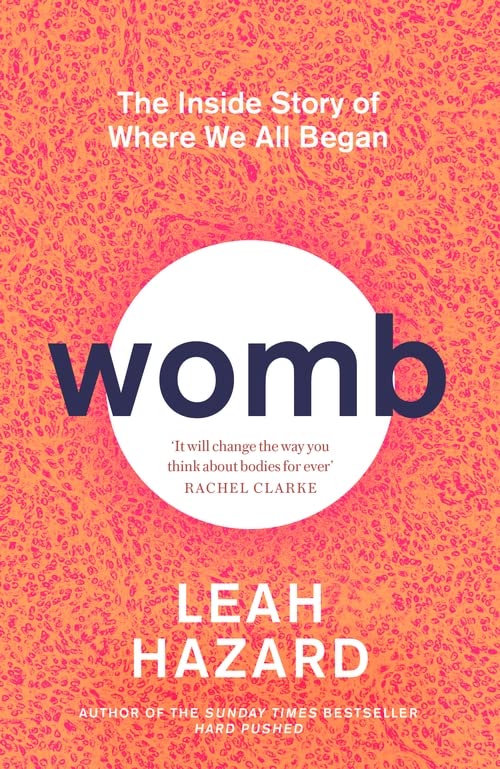

Womb: The Inside Story of Where We All Began by Leah Hazard

Back in 2019, I reviewed Hard Pushed, Leah Hazard’s memoir of being a midwife in a busy Glasgow hospital. Here she widens the view to create a wide-ranging and accessible study of the uterus. As magisterial in its field as Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Emperor of All Maladies was for cancer, it might have shared that book’s ‘A Biography’ subtitle and casts a feminist eye over history and future alike. Blending medical knowledge and cultural commentary, it cannot fail to have both personal and political significance for readers of any gender.

The thematic structure of the chapters also functions as a roughly chronological tour of how life with a uterus might proceed: menstruation, conception, pregnancy, labour, caesarean section, ongoing health issues, menopause. With much of Hazard’s research taking place at the height of the pandemic, she had to conduct many of her interviews online. She consults mostly female experts and patients, meeting people with surprisingly different opinions. For instance, she encounters opposing views on menstruation from American professors: one who believes it is now optional, a handicap – for teenagers, especially – and that the body was never meant to endure 350–400 periods compared to the historical average of 100 (based on shorter lifespan plus more frequent pregnancy and breastfeeding); versus another who is concerned about the cognitive effects of constant hormonal intervention.

The book forcefully conveys how gynaecological wellness is threatened by a lack of knowledge, sexist stereotypes, and devaluation of certain wombs. Even today, little is known about the placenta, she reports, so research involves creating organoids from stem cells that act like it would. The use of emotionally damaging language like “irritable/hostile uterus,” “incompetent cervix” and “too posh to push” is a major problem. The sobering chapter on “Reprocide” elaborates on enduring threats to reproductive freedom, such as non-consensual sterilization of women in detention centres and the revoking of abortion rights. And even routine problems like endometriosis and fibroids disproportionately affect women of colour.

Hazard has taken pains to adopt an inclusive perspective, referring to “menstruators” or “people with a uterus” as often as to women and mentioning health concerns specific to transgender people. She is also careful to depict the sheer variety of experience: age at first menses, subjective reactions to labour or hysterectomy, severity of menopause symptoms, and so on. Where events have potentially traumatic effects, she presents alternatives, such as a “gentle” or “natural” Caesarean, which is less clinical and more empowering. The prose is pitched at a good level for laypeople: conversational, and never bombarding with information. That I have not had children myself was no obstruction to my enjoyment of the book. It is full of fascinating content that is relevant to all (as in the Harry and Chris solidarity-themed song “Womb with a View,” which has the repeated line “we’ve all been in a womb”).

Here are just some of the mind-blowing facts I learned:

- Infant girls bleed in what as known as pseudomenses.

- Research is underway to regularly test menstrual effluent for endometriosis, etc. and the uterine microbiome for signs of cancer.

- The cervix can store sperm and release it later for optimal fertilization.

- Caesarean section and induction with oxytocin now occur in one-third of pregnancies, despite the WHO recommendation of no more than 10% for the former and the danger of postpartum haemorrhage with the latter.

- After childbirth, a discharge called lochia continues for 4–6 weeks.

- There have been successful uterine transplants from living donors and cadavers.

- Artificial wombs (“biobags”) have been used for other mammals and are in development; Hazard cautions about possible misogynistic exploitation.

With thanks to Virago Press for the free copy for review.

Rathbones Folio Prize Fiction Shortlist: Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout

I’ve enjoyed engaging with this year’s Rathbones Folio Prize shortlists, reading the entire poetry shortlist and two each from the nonfiction and fiction lists. These two I accessed from the library. Both Sheila Heti and Elizabeth Strout featured in the 5×15 event I attended on Tuesday evening, so in the reviews below I’ll weave in some insights from that.

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

Sheila Heti is a divisive author; I’m sure there are those who detest her indulgent autofiction, though I’ve loved it (How Should a Person Be? and especially Motherhood). But this is another thing entirely: Heti puts two fingers up to the whole notion of rounded characterization or coherent plot. This is the thinnest of fables, fascinating for its ideas and certainly resonant for me what with the themes of losing a parent and searching for purpose in life on an earth that seems doomed to destruction … but is it a novel?

My summary for Bookmarks magazine gives an idea of the ridiculous plot:

Heti imagines that the life we live now—for Mira, studying at the American Academy of American Critics, working in a lamp store, grieving her father, and falling in love with Annie—is just God’s first draft. In this creation myth of sorts, everyone is born a “bear” (lover), “bird” (achiever), or “fish” (follower). Mira has a mystical experience in which she and her dead father meet as souls in a leaf, where they converse about the nature of time and how art helps us face the inevitability of death. If everything that exists will soon be wiped out, what matters?

The three-creature classification is cute enough, but a copout because it means Heti doesn’t have to spend time developing Mira (a bird), Annie (a fish), or Mira’s father (a bear), except through surreal philosophical dialogues that may or may not take place whilst she is disembodied in a leaf. It’s also uncomfortable how Heti uses sexual language for Mira’s communion with her dead dad: “she knew that the universe had ejaculated his spirit into her”.

Heti explained that the book came to her in discrete chunks, from what felt like a more intuitive place than the others, which were more of an intellectual struggle, and that she drew on her own experience of grief over her father’s death, though she had been writing it for a year beforehand.

Indeed, she appears to be tapping into primordial stories, the stuff of Greek myth or Jewish kabbalah. She writes sometimes of “God” and sometimes of “the gods”: the former regretting this first draft of things and planning how to make things better for himself the second time around; the latter out to strip humans of what they care about: “our parents, our ambitions, our friendships, our beauty—different things from different people. They strip some people more and others less. They strip us of whatever they need to in order to see us more clearly.” Appropriately, then, we follow Mira all the way through to her end, when, stripped of everything but love, she rediscovers the two major human connections of her life.

Given Ali Smith’s love of the experimental, it’s no surprise that she as a judge shortlisted this. If you’re of a philosophical bent, don’t mind negligible/non-existent plot in your novels and aren’t turned off by literary pretension, you should be fine. If you are new to Heti or unsure about trying her, though, this is probably not the right place to start. See my Goodreads review for some sample quotes, good and bad.

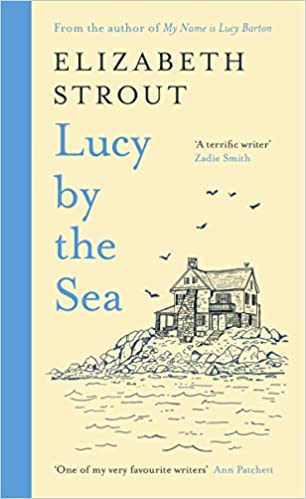

Lucy by the Sea by Elizabeth Strout

This was by far the best of the three Amgash books I’ve read. I think it must be the first time that Strout has set a book not in the past or at some undated near-contemporary moment but in the actual world with its current events, which inevitably means it gets political. I had my doubts about how successful she’d be with such hyper-realism, but this really worked.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

As Covid hits, William whisks Lucy away from her New York City apartment to a house at the coast in Crosby, Maine. She’s an Everywoman recounting the fear and confusion of those early pandemic days, hearing of friends and relatives falling ill and knowing there’s nothing she can do about it. Isolation, mostly imposed on her but partially chosen – she finally gets a writing studio, the first ‘room of her own’ she’s ever had – gives her time to ponder the trauma of her childhood and what went wrong in her marriage to William. She worries for her two adult daughters but, for the first time, you get the sense that the strength and wisdom she’s earned through bitter experience will help her support them in making good choices.

Here in rural Maine, Lucy sees similar deprivation to what she grew up with in Illinois and also meets real people – nice, friendly people – who voted for Trump and refuse to be vaccinated. I loved how Strout shows us Lucy observing and then, through a short story, compassionately imagining herself into the situation of conservative cops and drug addicts. “Try to go outside your comfort level, because that’s where interesting things will happen on the page,” is her philosophy. This felt like real insight into a writer’s inspirations.

Another neat thing Strout does here, as she has done before, is to stitch her oeuvre together by including references to most of her other books. So she becomes friends with Bob Burgess, volunteers alongside Olive Kitteridge’s nursing home caregiver (and I expect their rental house is supposed to be the one Olive vacated), and meets the pastor’s daughter from Abide with Me. My only misgiving is that she recounts Bob Burgess’s whole story, replete with spoilers, such that I don’t feel I need to read The Burgess Boys.

Lucy has emotional intelligence (“You’re not stupid about the human heart,” Bob Burgess tells her) and real, hard-won insight into herself (“My childhood had been a lockdown”). Readers as well as writers have really taken this character to heart, admiring her seemingly effortless voice. Strout said she does not think of this as a ‘pandemic novel’ because she’s always most interested in character. She believes the most important thing is the sound of the sentences and that a writer has to determine the shape of the material from the inside. She was very keen to separate herself from Lucy, and in fact came across as rather terse. I had somehow expected her to have a higher voice, to be warmer and softer. (“Ah, you’re not Lucy, you’re Olive!” I thought to myself.)

Predictions

This year’s judges are Guy Gunaratne, Jackie Kay and Ali Smith. Last year’s winner was a white man, so I’m going to say in 2023 the prize should go to a woman of colour, and in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if all three category winners were women of colour. My own taste in the shortlists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, very white-lady-ish and non-experimental. But I think Amy Bloom and Elizabeth Strout’s books are too straightforward and Fiona Benson’s not edgy enough. So I’m expecting:

Fiction: Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Nonfiction: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson

Poetry: Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (or Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa)

Overall winner: Constructing a Nervous System by Margo Jefferson (or Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley)

This is my 1,200th blog post!

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating.

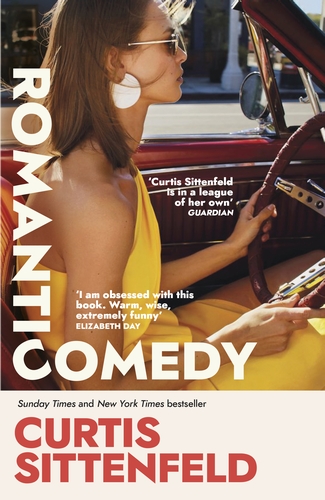

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating. Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.) The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,  Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Nancy appeals to the Colberts’ adult daughter, Rachel Blake, to accompany her on her walks so that Martin will not “overtake” her in the woods. Although none of the white characters take the repeated threat of attempted rape seriously enough, Henry and Rachel do eventually help Nancy escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. When Sapphira realizes her ‘property’ has been taken from her, she informs Rachel she is now persona non grata, but changes her mind when illness brings tragedy into Rachel’s household.

Nancy appeals to the Colberts’ adult daughter, Rachel Blake, to accompany her on her walks so that Martin will not “overtake” her in the woods. Although none of the white characters take the repeated threat of attempted rape seriously enough, Henry and Rachel do eventually help Nancy escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad. When Sapphira realizes her ‘property’ has been taken from her, she informs Rachel she is now persona non grata, but changes her mind when illness brings tragedy into Rachel’s household. Published when Thomas was in his mid-twenties, this is a series of 10 sketches, some of which are more explicitly autobiographical (as in first person, with a narrator named Dylan Thomas) than others. There is a rough chronological trajectory to the stories, with the main character a mischievous boy, then a grandstanding teenager, then a young journalist in his first job. The countryside and seaside towns of South Wales recur as settings, and – as will be no surprise to readers of Under Milk Wood – banter-filled dialogue is the priority. I most enjoyed the childhood japes in the first two pieces, “The Peaches” and “A Visit to Grandpa’s.” The rest failed to hold my attention, but I marked out two long passages that to me represent the voice and scene-setting that the Dylan Thomas Prize is looking for. The latter is the ending of the book and reminds me of the close of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” (University library)

Published when Thomas was in his mid-twenties, this is a series of 10 sketches, some of which are more explicitly autobiographical (as in first person, with a narrator named Dylan Thomas) than others. There is a rough chronological trajectory to the stories, with the main character a mischievous boy, then a grandstanding teenager, then a young journalist in his first job. The countryside and seaside towns of South Wales recur as settings, and – as will be no surprise to readers of Under Milk Wood – banter-filled dialogue is the priority. I most enjoyed the childhood japes in the first two pieces, “The Peaches” and “A Visit to Grandpa’s.” The rest failed to hold my attention, but I marked out two long passages that to me represent the voice and scene-setting that the Dylan Thomas Prize is looking for. The latter is the ending of the book and reminds me of the close of James Joyce’s “The Dead.” (University library) This was my second Arachne Press collection after

This was my second Arachne Press collection after  A couple of years ago I reviewed Evans’s second short story collection,

A couple of years ago I reviewed Evans’s second short story collection,  I was a big fan of Katherine May’s

I was a big fan of Katherine May’s  The title refers to a Middle Eastern dish (see this

The title refers to a Middle Eastern dish (see this  Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – This year’s Klara and the Sun for me: I have trouble remembering why I was so excited about Catton’s third novel that I put it on my

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton – This year’s Klara and the Sun for me: I have trouble remembering why I was so excited about Catton’s third novel that I put it on my  There is something very insular about this narrative, such that I had trouble gauging the passage of time. Raising the two birds, adopting street dogs, going on a pangolin patrol with a conservation charity – was this a matter of a couple of months, or were events separated by years? Ghana is an intriguing setting, yet because there is no attempt to integrate, she can only give a white outsider’s perspective on the culture, and indigenous people barely feature. I was sympathetic to the author’s feelings of loneliness and being trapped between countries, not belonging in either, but she overstates the lessons of compassion and freedom the finch taught. The writing, while informed and passionate about nature, needs a good polish (many misplaced modifiers, wrong prepositions, errors in epigraph quotes, homonym slips – “sight” instead of “site”; “balled” in place of “bawled”; “base” where it should be “bass,” twice – and so on). Still, it’s a promising debut from a valuable nature advocate, and I share her annual delight in welcoming England’s swifts, as in the scenes that open and close the book.

There is something very insular about this narrative, such that I had trouble gauging the passage of time. Raising the two birds, adopting street dogs, going on a pangolin patrol with a conservation charity – was this a matter of a couple of months, or were events separated by years? Ghana is an intriguing setting, yet because there is no attempt to integrate, she can only give a white outsider’s perspective on the culture, and indigenous people barely feature. I was sympathetic to the author’s feelings of loneliness and being trapped between countries, not belonging in either, but she overstates the lessons of compassion and freedom the finch taught. The writing, while informed and passionate about nature, needs a good polish (many misplaced modifiers, wrong prepositions, errors in epigraph quotes, homonym slips – “sight” instead of “site”; “balled” in place of “bawled”; “base” where it should be “bass,” twice – and so on). Still, it’s a promising debut from a valuable nature advocate, and I share her annual delight in welcoming England’s swifts, as in the scenes that open and close the book.

Through secondary characters, we glimpse other options for people of colour: one, Lucien Winters, is a shopkeeper (reminding me of the title character of The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho, a historical figure) but intends to move to Sierra Leone via a colonisation project; another passes as white to have a higher position in the theatre world. It felt odd, though, how different heritages were conflated, such that Zillah, of Caribbean descent, learns a few words of “Zulu” to speak to the Leopard Lady, and Lucien explains Africanness to her as if it is one culture. Perhaps this was an attempt to demonstrate solidarity among oppressed peoples.

Through secondary characters, we glimpse other options for people of colour: one, Lucien Winters, is a shopkeeper (reminding me of the title character of The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho, a historical figure) but intends to move to Sierra Leone via a colonisation project; another passes as white to have a higher position in the theatre world. It felt odd, though, how different heritages were conflated, such that Zillah, of Caribbean descent, learns a few words of “Zulu” to speak to the Leopard Lady, and Lucien explains Africanness to her as if it is one culture. Perhaps this was an attempt to demonstrate solidarity among oppressed peoples. A love of journalism kept Foo from committing suicide, got her into college and landed her podcast roles followed by her dream job with public radio programme This American Life in New York City. However, she struggled with a horrible, exacting boss and, when her therapist issued the diagnosis, she left to commit to the healing process, aided by her new partner, Joey. C-PTSD was named in the 1990s but is not recognised in the DSM; The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk is its alternative bible. Repeated childhood trauma, as opposed to a single event, rewires the brain to identify threats that might not seem rational, leading to self-destructive behaviour and difficulty maintaining healthy relationships.

A love of journalism kept Foo from committing suicide, got her into college and landed her podcast roles followed by her dream job with public radio programme This American Life in New York City. However, she struggled with a horrible, exacting boss and, when her therapist issued the diagnosis, she left to commit to the healing process, aided by her new partner, Joey. C-PTSD was named in the 1990s but is not recognised in the DSM; The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk is its alternative bible. Repeated childhood trauma, as opposed to a single event, rewires the brain to identify threats that might not seem rational, leading to self-destructive behaviour and difficulty maintaining healthy relationships.