A Bouquet of Spring Reading

In March through May I often try to read a few gardening-themed books and/or ones with “spring” in the title. Here are some of the ones that I have on the go as occasional reading:

Flowers and gardens

The Florist’s Daughter by Patricia Hampl: Her mother’s final illness led Hampl to reflect on her upbringing in St. Paul, Minnesota as the daughter of an Irish Catholic library clerk and a Czech florist. I love how she writes about small-town life and helping out in her father’s flower shop:

“These apparently ordinary people in our ordinary town, living faultlessly ordinary lives … why do I persist in thinking—knowing—they weren’t ordinary at all? … Nostalgia is really a kind of loyalty”

“it was my father’s domain, but it was also marvelously other, this place heavy with the drowsy scent of velvet-petaled roses and Provençal freesias in the middle of winter, the damp-earth spring fragrance of just-watered azaleas and cyclamen”

Led by the Nose: A Garden of Smells by Jenny Joseph: Joseph’s name might not sound familiar, but she was the author of the famous poem “Warning: When I Am an Old Woman I Shall Wear Purple” and died early last year. This is a pleasant set of short pieces about what you might see and sense in your garden month by month. “Gardeners do indeed look before and after, at the same time living, as no one else, in the now of the nose,” she maintains. I’m particularly fascinated by the sense of smell and how a writer can describe odors, so I was delighted to find this in a charity shop in Edinburgh last year and have been reading it a few pages at a time as a bedside book. I especially like the wood engravings by Yvonne Skargon that head each chapter.

Led by the Nose: A Garden of Smells by Jenny Joseph: Joseph’s name might not sound familiar, but she was the author of the famous poem “Warning: When I Am an Old Woman I Shall Wear Purple” and died early last year. This is a pleasant set of short pieces about what you might see and sense in your garden month by month. “Gardeners do indeed look before and after, at the same time living, as no one else, in the now of the nose,” she maintains. I’m particularly fascinated by the sense of smell and how a writer can describe odors, so I was delighted to find this in a charity shop in Edinburgh last year and have been reading it a few pages at a time as a bedside book. I especially like the wood engravings by Yvonne Skargon that head each chapter.

Green Thoughts: A Writer in the Garden by Eleanor Perényi: A somewhat dense collection of few-page essays, arranged in alphabetical order, on particular plants, tools and techniques. I tried reading it straight through last year and only made it as far as “Beans.” My new strategy is to keep it on my bedside shelves and dip into whichever pieces catch my attention. I don’t have particularly green fingers, so it’s not a surprise that my eye recently alighted on the essay “Failure,” which opens, “Sooner or later every gardener must face the fact that certain things are going to die on him. It is a temptation to be anthropomorphic about plants, to suspect that they do it to annoy.”

With One Lousy Free Packet of Seed by Lynne Truss (DNF at page 131 out of 210): A faltering gardening magazine is about to be closed down, but Osborne only finds out when he’s already down in Devon doing the research for his regular “Me and My Shed” column with a TV actress. Hijinks were promised as the rest of the put-out staff descend on Honiton, but by nearly the two-thirds point it all still felt like preamble, laying out the characters and their backstories, connections and motivations. My favorite minor character was Makepeace, a pugnacious book reviewer: “he used his great capacities as a professional know-all as a perfectly acceptable substitute for either insight or style.”

With One Lousy Free Packet of Seed by Lynne Truss (DNF at page 131 out of 210): A faltering gardening magazine is about to be closed down, but Osborne only finds out when he’s already down in Devon doing the research for his regular “Me and My Shed” column with a TV actress. Hijinks were promised as the rest of the put-out staff descend on Honiton, but by nearly the two-thirds point it all still felt like preamble, laying out the characters and their backstories, connections and motivations. My favorite minor character was Makepeace, a pugnacious book reviewer: “he used his great capacities as a professional know-all as a perfectly acceptable substitute for either insight or style.”

Spring

The Seasons, a Faber & Faber / BBC Radio 4 poetry anthology: From Chaucer and other Old English poets to Seamus Heaney (“Death of a Naturalist”) and Philip Larkin (“The Trees”), the spring section offers a good mixture of recent and traditional, familiar and new. A favorite passage was “May come up with fiddle-bows, / May come up with blossom, / May come up the same again, / The same again but different” (from “Nuts in May” by Louis MacNeice). Once we’re back from America I’ll pick up with the summer selections.

In the Springtime of the Year by Susan Hill: Early one spring, Ruth Bryce’s husband, Ben, dies in a forestry accident. They had only been married a year and here she is, aged twenty-one and a widow. Ben’s little brother, 14-year-old Jo, is a faithful visitor, but after the funeral many simply leave Ruth alone. I’m 100 pages in and still waiting for there to be a plot as such; so far it’s a lovely, quiet meditation on grief and solitude amid the rhythms of country life. Ben’s death is described as a “stone cast into still water,” and here at nearly the halfway point we’re seeing how some of the ripples spread out beyond his immediate family. I’m enjoying the writing more than in the three other Hill books I’ve read.

Absent in the Spring by Mary Westmacott: (The title doesn’t actually have anything to do with the season; it’s a quotation from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 98: “From you have I been absent in the spring.”) From 1944, this is the third of six novels Agatha Christie published under the alias Mary Westmacott. Joan Scudamore, traveling back to London from Baghdad after a visit to her adult daughter, encounters bad weather and misses her train, which leaves her stranded in the desert for days that feel more like weeks. We’re led back through scenes from Joan’s earlier life and realize that she’s utterly clueless about what those closest to her want and think. Rather like Olive Kitteridge, Joan is difficult in ways she doesn’t fully acknowledge. Like a desert mirage, the truth of who she’s been and what she’s done is hazy, and her realization feels a little drawn out and obvious. Once she gets back to London, will she act on what she’s discovered about herself and reform her life, or just slip back into her old habits? This is a short and immersive book, and a cautionary tale to boot. It examines the interplay between duty and happiness, and the temptation of living vicariously through one’s children.

Absent in the Spring by Mary Westmacott: (The title doesn’t actually have anything to do with the season; it’s a quotation from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 98: “From you have I been absent in the spring.”) From 1944, this is the third of six novels Agatha Christie published under the alias Mary Westmacott. Joan Scudamore, traveling back to London from Baghdad after a visit to her adult daughter, encounters bad weather and misses her train, which leaves her stranded in the desert for days that feel more like weeks. We’re led back through scenes from Joan’s earlier life and realize that she’s utterly clueless about what those closest to her want and think. Rather like Olive Kitteridge, Joan is difficult in ways she doesn’t fully acknowledge. Like a desert mirage, the truth of who she’s been and what she’s done is hazy, and her realization feels a little drawn out and obvious. Once she gets back to London, will she act on what she’s discovered about herself and reform her life, or just slip back into her old habits? This is a short and immersive book, and a cautionary tale to boot. It examines the interplay between duty and happiness, and the temptation of living vicariously through one’s children.

Have you been reading anything particularly appropriate for spring this year?

Four Recent Review Books: Butler, Hunt, Paralkar and Vestre

Four February–April releases: A quiet novel about the clash of religion and reason; a birdwatching odyssey in London; a folktale-inspired story of the undead descending on an Indian medical clinic; and a layman’s introduction to fetal development – you can’t say I don’t read a wide variety of books! See if any of these tempt you.

Little Faith by Nickolas Butler

Butler follows in Kent Haruf’s footsteps with this quiet story of ordinary Midwesterners facing a series of small crises. Lyle Hovde works at a local Wisconsin orchard but is more interested in spending time with Isaac, his five-year-old grandson. Lyle has been an atheist since he and Peg lost a child in infancy, making it all the more ironic that their adopted daughter, Shiloh, has recently turned extremely religious. She attends a large non-denominational church that meets in an old movie theatre and is engaged to Pastor Steven*, whose hardline opinions are at odds with his hipster persona.

Steven and Shiloh believe Isaac has a healing gift – perhaps he can even help Lyle’s old pal, Hoot, who’s just been diagnosed with advanced cancer? The main story line reminded me most of Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves (health and superstition collide) and Carolyn Parkhurst’s Harmony (the dangers of a charismatic leader). It’s all well and good to have faith in supernatural healing, but not if it means rejecting traditional medicine.

Steven and Shiloh believe Isaac has a healing gift – perhaps he can even help Lyle’s old pal, Hoot, who’s just been diagnosed with advanced cancer? The main story line reminded me most of Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves (health and superstition collide) and Carolyn Parkhurst’s Harmony (the dangers of a charismatic leader). It’s all well and good to have faith in supernatural healing, but not if it means rejecting traditional medicine.

This is the epitome of a slow burner, though: things don’t really heat up until the final 35 pages, and there were a few chapters that could have been cut altogether. The female characters struck me as underdeveloped, but I did have a genuine warm feeling for Lyle. There are some memorable scenes, like Lyle’s heroic effort to save the orchard from an ice storm – a symbolic act that’s more about his desperation to save his grandson from toxic religion. But mostly this is a book to appreciate for the slow, predictable rhythms of a small-town life lived by the seasons.

[*So funny because that’s my brother-in-law’s name! I’ve also visited a Maryland church that meets in a former movie theatre. I was a part of somewhat extreme churches and youth groups in my growing-up years, but luckily nowhere that would have advocated foregoing traditional medicine in favor of faith healing. There were a few false notes here that told me Butler was writing about a world he wasn’t familiar with.]

A favorite passage:

“‘Silent Night’ in a darkened country chapel was, to Lyle, more powerful than any atomic bomb. He was incapable of singing it without feeling his eyes go misty, without feeling that his voice was but one link in a chain of voices connected over the generations and centuries, that line we sometimes call family. Or memory itself.”

With thanks to Faber & Faber for the free copy for review.

The Parakeeting of London: An Adventure in Gonzo Ornithology by Nick Hunt

Rose-ringed parakeets were first recorded in London in the 1890s, but only in the last couple of decades have they started to seem ubiquitous. I remember seeing them clustered in treetops and flying overhead in various Surrey, Kent and Berkshire suburbs we’ve lived in. They’re even more noticeable in London’s parks and cemeteries. “When did they become as established as beards and artisan coffee?” Nick Hunt wonders about his home in Hackney. He and photographer Tim Mitchell set out to canvass public opinion about London’s parakeets and look into conspiracy theories about how they escaped (Henry VIII and Jimi Hendrix are rumored to have released them; the set of The African Queen is another purported origin) and became so successful an invasive species.

Rose-ringed parakeets were first recorded in London in the 1890s, but only in the last couple of decades have they started to seem ubiquitous. I remember seeing them clustered in treetops and flying overhead in various Surrey, Kent and Berkshire suburbs we’ve lived in. They’re even more noticeable in London’s parks and cemeteries. “When did they become as established as beards and artisan coffee?” Nick Hunt wonders about his home in Hackney. He and photographer Tim Mitchell set out to canvass public opinion about London’s parakeets and look into conspiracy theories about how they escaped (Henry VIII and Jimi Hendrix are rumored to have released them; the set of The African Queen is another purported origin) and became so successful an invasive species.

A surprising cross section of the population is aware of the birds, and opinionated about them. Language of “immigrants” versus “natives” comes up frequently in the interviews, providing an uncomfortable parallel to xenophobic reactions towards human movement – “people had a tendency to conflate the avian with the human, turning the ornithological into the political. Invading, colonizing, taking over.” This is a pleasant little book any Londoner or British birdwatcher in general would appreciate.

With thanks to Paradise Road for the free copy for review.

Night Theatre by Vikram Paralkar

This short novel has an irresistible (cover and) setup: late one evening a surgeon in a rural Indian clinic gets a visit from a family of three: a teacher, his pregnant wife and their eight-year-old son. But there’s something different about this trio: they’re dead. They each bear hideous stab wounds from being set upon by bandits while walking home late from a fair. In the afterlife, an angel reluctantly granted them a second chance at life. If the surgeon can repair their gashes before daybreak, and as long as they stay within the village boundaries, their bodies will be revivified at dawn.

This short novel has an irresistible (cover and) setup: late one evening a surgeon in a rural Indian clinic gets a visit from a family of three: a teacher, his pregnant wife and their eight-year-old son. But there’s something different about this trio: they’re dead. They each bear hideous stab wounds from being set upon by bandits while walking home late from a fair. In the afterlife, an angel reluctantly granted them a second chance at life. If the surgeon can repair their gashes before daybreak, and as long as they stay within the village boundaries, their bodies will be revivified at dawn.

Paralkar draws on dreams, folktales and superstition, and the descriptions of medical procedures are vivid, as you would expect given the author’s work as a research physician at the University of Pennsylvania. The double meaning of the word “theatre” in the title encompasses the operating theatre and the dramatic spectacle that is taking place in this clinic. But somehow I never got invested in any of these characters and what might happen to them; the précis is more exciting than the narrative as a whole.

A favorite passage:

“Apart from the whispering of the dead in the corridor, the silence was almost deliberate – as if the crickets had been bribed and the dogs strangled. The village at the base of the hillock was perfectly still, its houses like polyps erupting from the soil. The rising moon had dusted them all with white talc. They appeared to have receded in the hours after sunset, abandoning the clinic to its unnatural deeds.”

With thanks to Serpent’s Tail for the free copy for review.

The Making of You: A Journey from Cell to Human by Katharina Vestre

A sprightly layman’s guide to genetics and embryology, written by Doctoral Research Fellow at the University of Oslo Department of Biosciences. Addressed in the second person, as the title suggests, the book traces your development from the sperm Leeuwenhoek studied under a microscope up to labor and delivery. Vestre looks at all the major organs and the five senses and discusses what can go wrong along with the normal quirks of the body.

A sprightly layman’s guide to genetics and embryology, written by Doctoral Research Fellow at the University of Oslo Department of Biosciences. Addressed in the second person, as the title suggests, the book traces your development from the sperm Leeuwenhoek studied under a microscope up to labor and delivery. Vestre looks at all the major organs and the five senses and discusses what can go wrong along with the normal quirks of the body.

I learned all kinds of bizarre facts. For instance, did you know that sperm have a sense of smell? And that until the 1960s pregnancy tests involved the death of a mouse or rabbit? Who knew that babies can remember flavors and sounds experienced in utero?

Vestre compares human development with other creatures’, including fruit flies (with whom we share half of our DNA), fish and alligators (which have various ways of determining gender), and other primates (why is it that they stay covered in fur and we don’t?). The charming style is aimed at the curious reader; I rarely felt that things were being dumbed down. Most chapters open with a fetal illustration by the author’s sister. I’m passing this on to a pregnant friend who will enjoy marveling at everything that’s happening inside her.

A representative passage:

“This may not sound terribly impressive; I promised you dramatic changes, and all that’s happened is that a round plate has become a triple-decker cell sandwich. But you’re already infinitely more interesting than the raspberry you were a short while ago. These cells are no longer confused, needy newcomers with no idea where they are or what they’re supposed to do. They have completed a rough division of labour. The cells on the top layer will form, among other things, skin, hair, nails, eye lenses, nerves and your brain. From the bottom layer you’ll get intestines, liver, trachea and lungs. And the middle layer will become your bones, muscles, heart and blood vessels.”

With thanks to Wellcome Collection/Profile Books for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Hard Pushed: A Midwife’s Story by Leah Hazard

“For fans of Adam Kay’s This Is Going to Hurt and Christie Watson’s The Language of Kindness,” the blurb on my press release for Leah Hazard’s memoir opens. The publisher’s comparisons couldn’t be more perfect: Hard Pushed has the gynecological detail and edgy sense of humor of Kay’s book (“Another night, another vagina” is its first line, and the author has been known to introduce herself with “Midwife Hazard, at your cervix!”), and matches Watson’s with its empathetic picture of patients’ plights and medical professionals’ burnout.

Hazard alternates between anonymized case studies of patients she has treated and general thoughts on her chosen career (e.g. “Notes on Triage” and “Notes on Being from Somewhere Else”). Although all of the patients in her book are fictional composites, their circumstances are rendered so vividly that you quickly forget these particular characters never existed. Visceral details of sights, smells and feelings put you right there in the delivery room with Eleanor, one-half of a lesbian couple welcoming a child thanks to the now-everyday wonder of IVF; Hawa, a Somali woman whose pregnancy is complicated by the genital mutilation she underwent as a child; and Pei Hsuan, a Chinese teenager who was trafficked into sex work in Britain.

Sometimes we don’t learn the endings to these stories. Will 15-year-old Crystal have a healthy baby after she starts leaking fluid at 23 weeks? What will happen next for Pei Hsuan after her case is passed on to refugee services? Hazard deliberately leaves things uncertain to reflect the partial knowledge a hospital midwife often has of her patients: they’re taken off to surgery or discharged, and when they eventually come back to deliver someone else may be on duty. All she can do is to help each woman the best she can in the moment.

A number of these cases allow the author to comment on the range of modern opinions about pregnancy and childrearing, including some controversies. A pushy new grandmother tries to pressure her daughter into breastfeeding; a woman struggles with her mental health while on maternity leave; a rape victim is too far along to have a termination. At the other end of the spectrum, we meet a hippie couple in a birthing pool who prefer to speak of “surges” rather than contractions. Hazard rightly contends that it’s not her place to cast judgment on any of her patients’ decisions; her job is simply to deal with the situation at hand.

A number of these cases allow the author to comment on the range of modern opinions about pregnancy and childrearing, including some controversies. A pushy new grandmother tries to pressure her daughter into breastfeeding; a woman struggles with her mental health while on maternity leave; a rape victim is too far along to have a termination. At the other end of the spectrum, we meet a hippie couple in a birthing pool who prefer to speak of “surges” rather than contractions. Hazard rightly contends that it’s not her place to cast judgment on any of her patients’ decisions; her job is simply to deal with the situation at hand.

I especially liked reading about the habits that keep the author going through long overnight shifts, such as breaking the time up into 15-minute increments, each with its own assigned task. The excerpts from her official notes – in italics and full of shorthand and jargon – are a neat window into the science and reality of a midwife’s work, with a glossary at the end of the book ensuring that nothing is too technical for laypeople.

Hazard, an American, lives in Scotland and has a Glaswegian husband and two daughters. Her experience of being an NHS midwife has not always been ideal; there were even moments when she was ready to quit. Like Kay and Watson, she has found that the medical field can be unforgiving what with low pay, little recognition and hardly any time to wolf down your dinner during a break, let alone reflect on the life-and-death situations you’ve been a part of. Yet its rewards outweigh the downsides.

Hard Pushed has none of the sentimentality of Call the Midwife – a relief since I’m not one to gush over babies. Still, it’s a heartfelt read as well as a vivid and pacey one, and it’s alternately funny and sobering. If you like books that follow doctors and nurses down hospital hallways, you’ll love it. This was one of my most anticipated books of the first half of the year, and it lived up to my expectations. It’s also one of my top contenders for the 2020 Wellcome Book Prize so far.

A few favorite passages:

“So many things in midwifery are ‘wee’ [in Scotland, at least!] – a wee cut, a wee tear, a wee bleed, the latter used to describe anything from a trickle to a torrent. Euphemisms are one of our many small mercies: we learn early on to downplay and dissemble. The brutality of birth is often self-evident; there is little need to elaborate.”

“Whenever I dress a wound in this way, I remember that this is an act of loving validation; every wound tells a story, and every dressing is an acknowledgement of that story – the midwife’s way of saying, I hear you, and I believe you.”

“midwives do so much more than catch babies. We devise and implement plans of care; we connect, console, empathise and cheerlead; we prescribe; we do minor surgery. … We may never have met you until the day we ride into battle for you and your baby; … you may not even recognise the cavalry that’s been at your back until the drapes are down and the blood has dried beneath your feet.”

My rating:

Hard Pushed was published in the UK on May 2nd (just a few days before International Midwives’ Day) by Hutchinson. My thanks to the publisher for the free proof copy for review.

The Wellcome Book Prize 2019 Awards Ceremony

The winner of the 10th anniversary Wellcome Book Prize is Murmur, Will Eaves’s experimental novel about Alan Turing’s state of mind and body after being subjected to chemical castration for homosexuality. It is the third novel to win the Prize. Although it fell in the middle of the pack in our shadow panel voting because of drastically differing opinions, it was a personal favorite for Annabel and myself – though we won’t gloat (much) for predicting it as the winner!

Clare, Laura and I were there for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. It was also lovely to meet Chloe Metzger, another book blogger who was on the blog tour, and to see UK book v/blogging legends Eric Karl Anderson and Simon Savidge again.

The judges’ chair, novelist Elif Shafak, said, “This prize is very special. It opens up new and vital conversations and creates bridges across disciplines.” At a time when we “are pushed into monolithic tribes and artificial categories, these interdisciplinary conversations can take us out of our comfort zones, encouraging cognitive flexibility.” She praised the six shortlisted books for their energy and the wide range of styles and subjects. “Each book, each author, from the beginning, has been treated with the utmost respect,” she reassured the audience, and the judges approached their task with “an open mind and an open heart,” arriving at an “inspiring, thought-provoking, but we believe also accessible, shortlist.”

The judges brought each of the five authors present (all but Thomas Page McBee) onto the stage one at a time for recognition. Shafak admired how Sandeep Jauhar weaves together his professional expertise with stories in Heart, and called Sarah Krasnostein’s The Trauma Cleaner a “strangely life-affirming and uplifting book about a remarkable woman. … It’s about transitions.”

Doctor and writer Kevin Fong championed Amateur, his answer to the question “which of these books, if I gave it to someone, would make them better.” McBee’s Canongate editor received the recognition/flowers on the author’s behalf.

Writer and broadcaster Rick Edwards chose Arnold Thomas Fanning’s Mind on Fire for its “pressability factor” – the book about which he kept saying to friends and family, “you must read this.” It’s an “uncomfortably honest” memoir, he remarked, “a vivid and unflinching window, and for me it was revelatory.”

Writer, critic and academic Jon Day spoke up for Murmur, “a novel of great power and astonishing achievement,” about “what it means to know another person.”

Lastly, writer, comedian and presenter Viv Groskop spoke about Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which she described as “Jane Eyre meets Prozac Nation.” The judges “had a lot of fun” with this novel, she noted; it’s “caustic, feminist … original, playful, [and] strangely profound.”

But only one book could win the £30,000 10th anniversary prize, and it was one that Shafak predicted will be “a future classic,” Murmur. Will Eaves thanked Charles Boyle of CB Editions for taking a chance on his work. He also acknowledged Alan Turing, who, like him, attended King’s College, Cambridge. As he read Turing’s papers, Eaves reported, he was gripped by the quality of the writing – “there’s a voice there.” Finally, in a clearly emotional moment, he thanked his mother, who died several years ago and grew up in relative poverty. She was a passionate believer in education, and Eaves encouraged the audience to bear in mind the value of a state education when going to the polls.

Photo by Eric Karl Anderson.

After the announcement we found Sarah Krasnostein, our shadow panel winner, and got a photo and a signature. She gave us the scoop on her work-in-progress, which examines six case studies, three from Australia and three from the USA, of people with extreme religious or superstitious beliefs, such as a widow who believes her husband was abducted by aliens. She’s exploring the “cognitive dissonance” that goes on in these situations, she said. Can’t wait for the new book!

Laura, Sarah Krasnostein, me, Clare.

I also congratulated Will Eaves, whose book I’d covered for the blog tour, and got a signature. Other ‘celebrities’ spotted: Suzanne O’Sullivan, Ruth Padel and Robin Robertson. (Also a couple of familiar faces from Twitter that I couldn’t place, one of whom I later identified as Katya Taylor.)

I again acquired a Wellcome goody bag: this year’s limited-edition David Shrigley tote (I now have two so will pass one on to Annabel, who couldn’t be there) with an extra copy of The Trauma Cleaner to give to my sister.

Another great year of Wellcome festivities! Thanks to Midas PR, the Wellcome Book Prize and my shadow panel. Looking forward to next year already – I have a growing list of 2020 hopefuls I’ve read or intend to read.

See also: Laura’s post on the ceremony and the 5×15 event that took place the night before.

Classics and Doorstoppers of the Month

April was something of a lackluster case for my two monthly challenges: two slightly disappointing books were partially read (and partially skimmed), and two more that promise to be more enjoyable were not finished in time to review in full.

Classics

Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor (1952)

When Hazel Motes, newly released from the Army, arrives back in Tennessee, his priorities are to get a car and to get laid. In contrast to his preacher grandfather, “a waspish old man who had ridden over three counties with Jesus hidden in his head like a stinger,” he founds “The Church Without Christ.” Heaven, hell and sin are meaningless concepts for Haze; “I don’t have to run from anything because I don’t believe in anything,” he declares. But his vociferousness belies his professed indifference. He’s particularly invested in exposing Asa Hawkes, a preacher who vowed to blind himself, but things get complicated when Haze is seduced by Hawkes’s 15-year-old illegitimate daughter, Sabbath – and when his groupie, eighteen-year-old Enoch Emery, steals a shrunken head from the local museum and decides it’s just the new Jesus this anti-religion needs. O’Connor is known for her very violent and very Catholic vision of life. In a preface she refers to this, her debut, as a comic novel, but I found it bizarre and unpleasant and only skimmed the final two-thirds after reading the first 55 pages.

When Hazel Motes, newly released from the Army, arrives back in Tennessee, his priorities are to get a car and to get laid. In contrast to his preacher grandfather, “a waspish old man who had ridden over three counties with Jesus hidden in his head like a stinger,” he founds “The Church Without Christ.” Heaven, hell and sin are meaningless concepts for Haze; “I don’t have to run from anything because I don’t believe in anything,” he declares. But his vociferousness belies his professed indifference. He’s particularly invested in exposing Asa Hawkes, a preacher who vowed to blind himself, but things get complicated when Haze is seduced by Hawkes’s 15-year-old illegitimate daughter, Sabbath – and when his groupie, eighteen-year-old Enoch Emery, steals a shrunken head from the local museum and decides it’s just the new Jesus this anti-religion needs. O’Connor is known for her very violent and very Catholic vision of life. In a preface she refers to this, her debut, as a comic novel, but I found it bizarre and unpleasant and only skimmed the final two-thirds after reading the first 55 pages.

In progress: Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee (1959) – I love to read ‘on location’ when I can, so this was a perfect book to start during a weekend when I visited Stroud, Gloucestershire for the first time.* Lee was born in Stroud and grew up there and in the neighboring village of Slad. I’m on page 65 and it’s been a wonderfully evocative look at a country childhood. The voice reminds me slightly of Gerald Durrell’s in his autobiographical trilogy.

*We spent one night in Stroud on our way home from a short holiday in Devon so that I could see The Bookshop Band and member Beth Porter’s other band, Marshes (formerly Beth Porter and The Availables) live at the Prince Albert pub. It was a terrific night of new songs and old favorites. I also got to pick up my copy of the new Marshes album, When the Lights Are Bright, which I supported via an Indiegogo campaign, directly from Beth.

Doorstoppers

The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas (2017)

Joan Ashby’s short story collection won a National Book Award when she was 21 and was a bestseller for a year; her second book, a linked story collection, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. In contravention of her childhood promise to devote herself to her art, she marries Martin Manning, an eye surgeon, and is soon a mother of two stuck in the Virginia suburbs. Two weeks before Daniel’s birth, she trashes a complete novel. Apart from a series of “Rare Babies” stories that never circulate outside the family, she doesn’t return to writing until both boys are in full-time schooling. When younger son Eric quits school at 13 to start a computer programming business, she shoves an entire novel in a box in the garage and forgets about it.

I chose this for April based on the Easter-y title (it’s a stretch, I know!).

Queasy feelings of regret over birthing parasitic children – Daniel turns out to be a fellow writer (of sorts) whose decisions sap Joan’s strength – fuel the strong Part I, which reminded me somewhat of Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook in that the protagonist is trying, and mostly failing, to reconcile the different parts of her identity. However, this debut novel is indulgently long, and I lost interest by Part III, in which Joan travels to Dharamshala, India to reassess her relationships and career. I skimmed most of the last 200 pages, and also skipped pretty much all of the multi-page excerpts from Joan’s fiction. At a certain point it became hard to sympathize with Joan’s decisions, and the narration grew overblown (“arc of tragedy,” “tortured irony,” etc.) [Read instead: Forty Rooms by Olga Grushin]

Page count: 523

In progress: Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly, a 613-page historical novel in verse narrated by a semi-literate servant from Stroud, then a cloth mill town. I’d already committed to read it for a Nudge/New Books magazine review, having had my interest redoubled by its shortlisting for the Rathbones Folio Prize, but it was another perfect choice for a weekend that involved a visit to that part of Gloucestershire. Once you’re in the zone, and so long as you can guarantee no distractions, this is actually a pretty quick read. I easily got through the first 75 pages in a couple of days.

My Stroud-themed reading.

Next month’s plan: As a doorstopper Annabel and I are going to read The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon (636 pages, or roughly 20 pages a day for the whole month of May). Join us if you like! I’m undecided about a classic, but might choose between George Eliot, William Faulkner, Robert Louis Stevenson and Emile Zola.

Library Checkout: April 2019

This was a huge library reading month for me! I finished off a lot of books that I’d started last month, several of which were requested after me, and picked up a novel from the Women’s Prize longlist plus a few that have attracted a lot of buzz. Looking ahead, I’ve placed holds on a bunch of recent nonfiction: nature, medicine, current events and essays. [I give links to reviews of any books that I haven’t already featured on the blog in some way, and ratings for all.]

What have you been reading from your local library? I don’t have an official link-up system, so please just pop a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout this month. Feel free to use this image in your post.

LIBRARY BOOKS READ

- A Breath of French Air, H.E. Bates

- 21st-Century Yokel by Tom Cox

- Murmur by Will Eaves

- Also Human: The Inner Lives of Doctors by Caroline Elton

- Ordinary People by Diana Evans

- Faces in the Water by Janet Frame

- The Garden of Eden by Ernest Hemingway

- Injury Time by Clive James [poetry]

- Lanny by Max Porter

- The World I Fell Out Of by Melanie Reid

- Daisy Jones & the Six, Taylor Jenkins Reid

- Bottled Goods by Sophie van Llewyn

- The Dreamers, Karen Thompson Walker

SKIMMED

- Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-wage Britain by James Bloodworth

- It’s All a Game: A Short History of Board Games by Tristan Donovan

- The Village News: The Truth behind England’s Rural Idyll by Tom Fort

- Outsiders: Five Women Writers Who Changed the World by Lyndall Gordon

- The Recovering: Intoxication and Its Aftermath by Leslie Jamison

- To Obama: With Love, Joy, Hate and Despair by Jeanne Marie Laskas

- Amateur: A Reckoning with Gender, Identity and Masculinity by Thomas Page McBee [a look back through before finalizing our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel vote]

- Lost and Found: Memory, Identity, and Who We Become when We’re No Longer Ourselves by Jules Montague

- Still Water: The Deep Life of the Pond by John Lewis-Stempel

- The Uninhabitable Earth: A Story of the Future by David Wallace-Wells

CURRENTLY READING

- Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson

- I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer by Michelle McNamara

- The Crossway by Guy Stagg

CURRENTLY SKIMMING

- The Seasons, a Faber & Faber / BBC Radio 4 poetry anthology (the “Spring” section, naturally)

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Stroke: A 5% Chance of Survival by Ricky Monahan Brown

- Because: A Lyric Memoir by Joshua Mensch

- The Lost Properties of Love: An Exhibition of Myself by Sophie Ratcliffe

- First Time Ever by Peggy Seeger

- The Butcher’s Hands [poetry] by Catherine Smith

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

- Our Place: Can We Save Britain’s Wildlife before It Is Too Late? by Mark Cocker

- How to Catch a Mole and Find Yourself in Nature by Marc Hamer

- Under the Camelthorn Tree: Raising a Family among Lions by Kate Nicholls

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- How to Treat People: A Nurse’s Notes by Molly Case

- Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene

- Lowborn: Growing Up, Getting Away and Returning to Britain’s Poorest Towns by Kerry Hudson

- Horizon by Barry Lopez

- The Doll Factory by Elizabeth Macneal

- The Electricity of Every Living Thing: One Woman’s Walk with Asperger’s by Katherine May

- Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan

- The Wild Remedy: How Nature Mends Us: A Diary by Emma Mitchell

- Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

- Feel Free: Essays by Zadie Smith

- A Farmer’s Diary: A Year at High House Farm by Sally Urwin

- Frankisstein: A Love Story by Jeanette Winterson

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Seven Signs of Life: Stories from an Intensive Care Doctor by Aoife Abbey

- Remembered by Yvonne Battle-Felton

RETURNED UNREAD

- The Pebbles on the Beach: A Spotter’s Guide by Clarence Ellis

- Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli

- Taking the Arrow out of the Heart by Alice Walker [poetry]

- The Face Pressed against a Window: A Memoir by Tim Waterstone

(I lost interest in all of these.)

Does anything appeal from my stacks?

Wellcome Book Prize 2019: Our Shadow Panel Winner Is…

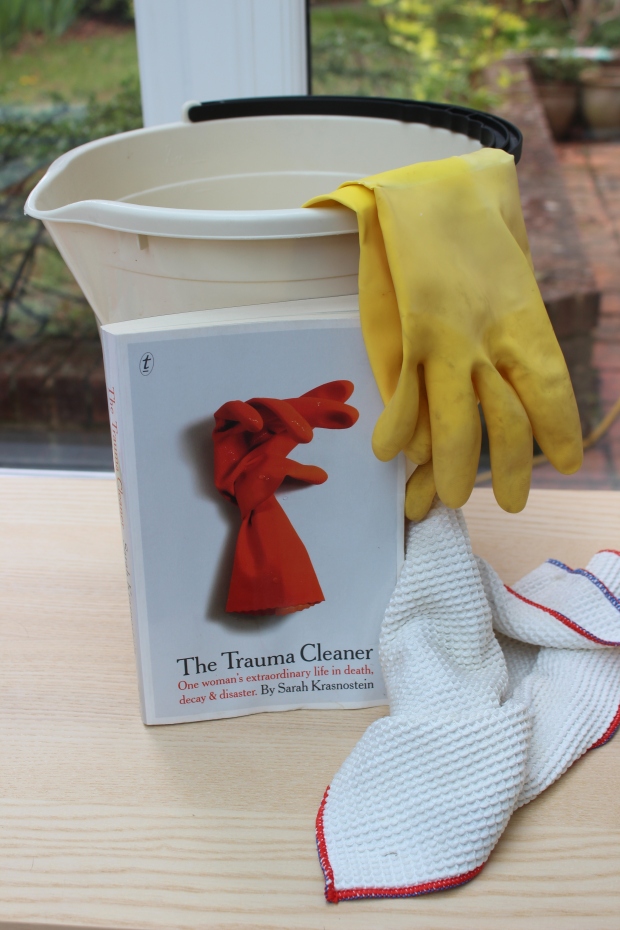

The Trauma Cleaner: One Woman’s Extraordinary Life in Death, Decay and Disaster by Sarah Krasnostein

This year there was no clear favourite among the shadow panel. Two of us picked one book as our favourite, two picked another, and a third picked yet another book! However, by each person assigning each book a point value from 1 to 6, we were able to decide based on the one that got the most points in total. (Though there was only 1 point separating our first place from our runner-up!)

Here’s what the shadow panel have to say about our pick:

Annabel: “I was glad to have read this book. It was an easy read despite its oft grim subject matter, fascinating and very sympathetic too.”

Clare: “The structure of the book reveals the many layers and contradictions of Sandra gradually … even though it’s one of the least objective biographies I’ve read in a very long time, it is also one of the most memorable and fascinating.”

Laura: “The Trauma Cleaner is a book it will be difficult to forget in a hurry. … Krasnostein is rightly impressed by Sandra’s resilience, and, in telling her story, she makes the right choice, I think, to remain as a largely invisible presence.”

Paul: “Pankhurst is one remarkable lady, even after a horrendous childhood and working in the prostitution trade, she has an amazing amount of empathy for all of her clients. … if you want to have a no-holds-barred look at a part of society that almost everyone will be unaware of then this is one to read.”

Rebecca: “I guarantee you’ve never read a biography quite like this one. … It’s part journalistic exposé and part ‘love letter’; it’s part true crime and part ordinary life story. It considers gender, mental health, addiction, trauma and death. It’s also simply a terrific read that should draw in lots of people who wouldn’t normally pick up nonfiction.”

Photo by Annabel Gaskell.

On Wednesday, at an evening ceremony at the Wellcome Collection, we will find out which book the official judges have chosen as the winner of the 10th anniversary prize. I have no idea who it will be!

Who are you rooting for?

Stanley and Elsie by Nicola Upson & A Visit to Sandham Memorial Chapel

“I don’t want them to look like war paintings, Elsie. I want them to look like heaven.”

When I was offered a copy of this novel to review as part of the blog tour, I was unfamiliar with the name of its subject, the artist Sir Stanley Spencer (1891–1959) – until I realized that he painted the WWI-commemorative Sandham Memorial Chapel in Hampshire, which I had never visited* but knew was just 5.5 miles from our home in Berkshire.

Take another look at the title, though: two characters are given double billing, the second of whom is Elsie Munday, who in the opening chapter presents herself for an interview with Stanley and his wife, Hilda (also a painter), who promptly hire her to be their housemaid at Chapel View in 1928. This creates a setup similar to that in Girl with a Pearl Earring, with a lower-class character observing the inner workings of an artist’s household and giving plain-speaking commentary on what she sees. Upson’s close third-person narration sticks with Elsie for the whole of Part I, but in Part II the picture widens out, with the point of view rotating between Hilda, Elsie and Dorothy Hepworth, the reluctant third side in a love triangle that develops between Stanley and her partner, Patricia Preece.

Hilda and Stanley argue about everything, from childrearing to art: they even paint dueling portraits of Elsie – with Hilda’s Country Girl winning out. Elsie knows she’s lucky to have such a comfortable position with the Spencers and their daughters at Burghclere, and later at Cookham, but she’s uneasy at how Stanley turns her into a confidante in his increasingly tempestuous marriage. Hilda, frustrated at Stanley’s selfish, demanding ways, often returns to her family home in Hampstead, leaving Elsie alone with her employer. Stanley doesn’t give a fig for local opinion, but Elsie knows she has a reputation to protect – especially considering that her moments alone with Stanley aren’t entirely free of sexual tension.

I love reading about artists’ habits – how creative work actually gets done – so I particularly loved the scenes where Elsie, sent on errands, finds Stanley up a ladder in the chapel, pondering how to get a face or object just right. On more than one occasion he borrows her kitchen items, such as a sponge and cooked and uncooked rashers of bacon, so he can render them perfectly in his paintings. I also loved that this is a local interest book for me, with Newbury, where I live, mentioned four or five times in passing as the nearest big town. Part II, with its account of Stanley’s extramarital doings becoming ever more sordid, didn’t grip me as much as Part I, but I found the whole to be an elegantly written study of a very difficult man and the ties that he made and broke over the course of several decades.

I love reading about artists’ habits – how creative work actually gets done – so I particularly loved the scenes where Elsie, sent on errands, finds Stanley up a ladder in the chapel, pondering how to get a face or object just right. On more than one occasion he borrows her kitchen items, such as a sponge and cooked and uncooked rashers of bacon, so he can render them perfectly in his paintings. I also loved that this is a local interest book for me, with Newbury, where I live, mentioned four or five times in passing as the nearest big town. Part II, with its account of Stanley’s extramarital doings becoming ever more sordid, didn’t grip me as much as Part I, but I found the whole to be an elegantly written study of a very difficult man and the ties that he made and broke over the course of several decades.

For the tone as well as the subject matter, I would particularly recommend it to readers of Jonathan Smith’s Summer in February and Graham Swift’s Mothering Sunday, and especially Esther Freud’s Mr. Mac and Me.

My rating:

Stanley and Elsie will be published by Duckworth on May 2nd. My thanks to the publisher for the proof copy for review. They also sent a stylish tote bag!

Nicola Upson

Nicola Upson is best known for her seven Josephine Tey crime novels. She has also published nonfiction, including a book on the sculpture of Helaine Blumenfeld. This is her first stand-alone novel.

*Until now. On a gorgeous Easter Saturday that felt more like summer than spring, I had my husband drop me off on his way to a country walk so I could tour the chapel. I appreciated Spencer’s “holy box” so much more having read the novel than I ever could have otherwise – even though the paintings were nothing like I’d imagined from Upson’s descriptions.

You enter the chapel through the wooden double doors at the center.

What struck me immediately is that, for war art, the focus is so much more on domesticity. Spencer briefly served in Salonika, Macedonia (like his patrons’ brother, Harry Sandham, to whose memory the chapel is dedicated), but had initially been rejected by the army and started off as a medical orderly in an English hospital. Both Salonika and Beaufort hospital appear in the paintings, but there are no battle scenes or bloody injuries. Instead we see tableaux of cooking, doing laundry, making beds, inventorying kitbags, filling canteens, reading maps, dressing under mosquito nets and making stone mosaics. It’s as if Spencer wanted to spotlight what happens in between the fighting. These everyday activities would have typified the soldiers’ lives more than active combat, after all.

I was reminded of how Stanley explains his approach in the novel:

“There’s something heroic in the everyday, don’t you think?”

“Isn’t that what peace is sometimes? A succession of bland moments? We have to cherish them, though, otherwise what was the point of fighting for them?”

The paintings show inventive composition but are in an unusual style that sometimes verges on the grotesque. Many of the figures are lumpen and childlike, especially in Tea in the Hospital Ward, where the soldiers scoffing bread and jam look like cheeky schoolboys. There are lots of animals on display, especially horses and donkeys, but they often look enormous and not entirely realistic. The longer you look, the more details you spot, like a dog raiding a stash of Fray Bentos tins and a young man looking at his reflection in a picture frame to part his hair with a comb. These aren’t desolate, burnt-out landscapes but rich with foliage and blossom, even in Macedonia, which recalls the Holy Land and seems timeless.

The central painting behind the altar, The Resurrection of the Soldiers, imagines the dead rising out of their graves, taking up their white crosses and delivering them to Jesus, a white-clad figure in the middle distance. There’s an Italian Renaissance feeling to this one, with one face in particular looking like it could have come straight out of Giotto (an acknowledged influence on Spencer’s chapel work). It’s as busy as Bosch, but not as dark thematically or in terms of the color scheme – while some of the first paintings in the sequence, like the one of scrubbing hospital floors, recall Edward Hopper with their somber realism. We see all these soldiers intact: at their resurrection they are whole, with no horrific wounds or humiliating nudity. Like Stanley says to Elsie, it’s more heaven than war.

If you are ever in the area, I highly recommend even a quick stop at this National Trust property. I showed a few workers my advanced copy of the novel; while the reception staff were unaware of its existence, a manager I caught up with after my tour knew about it and had plans to read it soon. She also said they will stock it in the NT shop on site.

Rathbones Folio Prize Shortlist: The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus

The Rathbones Folio Prize is unique in that nominations come from The Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, and any book written in English is eligible, so there’s nonfiction and poetry as well as fiction on this year’s varied shortlist of eight titles:

Can You Tolerate This? by Ashleigh Young [essays]

Can You Tolerate This? by Ashleigh Young [essays]- The Crossway by Guy Stagg [travel memoir]

- Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly [historical fiction]

- Milkman by Anna Burns [literary fiction]

- Ordinary People by Diana Evans [literary fiction]

- The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus [poetry]

- There There by Tommy Orange [literary fiction]

- West by Carys Davies [historical fiction]

I’m helping to kick off the Prize’s social media tour by championing the debut poetry collection The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus (winner of the 2018 Geoffrey Dearmer Award from the Poetry Society), issued by the London publisher Penned in the Margins last year. Antrobus is a British-Jamaican poet with an MA in Spoken Word Education who has held multiple residencies in London schools and works as a freelance teacher and poet. His poems dwell on the uneasiness of bearing a hybrid identity – he’s biracial and deaf but functional in the hearing world – and reflect on the loss of his father and the intricacies of Deaf history.

I was previously unaware of the difference between “deaf” and “Deaf,” but it’s explained in the book’s endnotes: Deaf refers to those who are born deaf and learn sign before any spoken language, so they tend to consider deafness part of their cultural identity; deaf means that the deafness was acquired later in life and is a medical consequence rather than a defining trait.

The opening poem, “Echo,” recalls how Antrobus’s childhood diagnosis came as a surprise because hearing problems didn’t run in the family.

I sat in saintly silence

during my grandfather’s sermons when he preached

The Good News I only heard

as Babylon’s babbling echoes.

Raymond Antrobus. Photo credit: Caleb Femi.

Nowadays he uses hearing aids and lip reading, but still frets about how much he might be missing, as expressed in the prose poem “I Move through London like a Hotep” (his mishearing when a friend said, “I’m used to London life with no sales tax”). But if he had the choice, would Antrobus reverse his deafness? As he asks himself in one stanza of “Echo,” “Is paradise / a world where / I hear everything?”

Learning how to live between two worlds is a major theme of the collection, applying not just to the Deaf and hearing communities but also to the balancing act of a Black British identity. I first encountered Antrobus through the recent Black British poetry anthology Filigree (I assess it as part of a review essay in an upcoming issue of Wasafiri literary magazine), which reprints his poem “My Mother Remembers.” A major thread in that volume is art as a means of coming to terms with racism and constructing an individual as well as a group identity. The ghazal “Jamaican British” is the clearest articulation of that fight for selfhood, reinforced by later poems on being called a foreigner and harassment by security staff at Miami airport.

The title comes from the name of the pub where Antrobus’s father drank while his son waited outside. The title poem is an elegant sestina in which “perseverance” is the end word of one line per stanza. The relationship with his father is a connecting thread in the book, culminating in the several tender poems that close the book. Here he remembers caring for his father, who had dementia, in the final two years of his life, and devotes a final pantoum to the childhood joy of reading aloud with him.

The title comes from the name of the pub where Antrobus’s father drank while his son waited outside. The title poem is an elegant sestina in which “perseverance” is the end word of one line per stanza. The relationship with his father is a connecting thread in the book, culminating in the several tender poems that close the book. Here he remembers caring for his father, who had dementia, in the final two years of his life, and devotes a final pantoum to the childhood joy of reading aloud with him.

A number of poems broaden the perspective beyond the personal to give a picture of early Deaf history. Several mention Alexander Graham Bell, whose wife and mother were both deaf, while in one the ghost of Laura Bridgeman (the subject of Kimberly Elkins’s excellent novel What Is Visible) warns Helen Keller about the unwanted fame that comes with being a poster child for disability. The poet advocates a complete erasure of Ted Hughes’s offensive “Deaf School” (sample lines: “Their faces were alert and simple / Like faces of little animals”; somewhat ironically, Antrobus went on to win the Ted Hughes Award last month!) and bases the multi-part “Samantha” on interviews with a Deaf Jamaican woman who moved to England in the 1980s. The text also includes a few sign language illustrations, including numbers that mark off section divisions.

The Perseverance is an issues book that doesn’t resort to polemic; a bereavement memoir that never turns overly sentimental; and a bold statement of identity that doesn’t ignore complexities. Its mixture of classical forms and free verse, the historical and the personal, makes it ideal for those relatively new to poetry, while those who enjoy the sorts of poets he quotes and tips the hat to (like Kei Miller, Danez Smith and Derek Walcott) will find a resonant postcolonial perspective.

A favorite passage from “Echo” (I’m a sucker for alliteration):

the ravelled knot of tongues,

of blaring birds, consonant crumbs

of dull doorbells, sounds swamped

in my misty hearing aid tubes.

The winner of the Rathbones Folio Prize will be announced on May 20th.

My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

Swan Song by Kelleigh Greenberg-Jephcott: Full of glitzy atmosphere contrasted with washed-up torpor. I have no doubt the author’s picture of Truman Capote is accurate, and there are great glimpses into the private lives of his catty circle. I always enjoy first person plural narration, too. However, I quickly realized I don’t have sufficient interest in the figures or time period to sustain me through nearly 500 pages. I read the first 18 pages and skimmed to p. 35.

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker