The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo

I have a soft spot for uncategorizable nonfiction like this. My expectation was for a food memoir, but while the essays incorporate shards of autobiography and, yes, recipes, they also dive into everything from botany and cultural history to medicinal uses. Kate Lebo has a finger in many pies – a figure of speech I use deliberately, as she is primarily a baker (but also a poet) and her three previous books are about pie.

You won’t find any ordinary apples or oranges here. Difficult fruit – “the Tart, Tender, and Unruly,” as the subtitle elaborates – is different: rarer to find, more challenging to process, perhaps harder to love. Instead of bananas and pears, then, you’ll read about the niche (aronia and thimbleberries), the rotten and malodorous (medlars and durian fruit), and the downright inedible (just one: the Osage orange, only suitable for repelling spiders or turning into decorations). These fruits might be foraged on hikes, sent by friends and relatives in other parts of the USA, or sold at Lebo’s local Spokane, Washington farmer’s market. Occasionally the ‘recipes’ are for non-food items, such as a pomegranate face mask or yuzu body oil.

The A-to-Z format required some creativity and occasions great trivia but also poignant stories. J is for juniper berry, a traditional abortifacient, and brings to mind for Lebo the time she went to Denver to accompany a friend to an abortion appointment. N is for the Norton grape, an American variety whose wine is looked down upon compared to European cultivars. Q is for quince, what Eve likely ate in the Garden of Eden; like the first humans in the biblical account, Lebo’s pair of adopted aunts were cast out for their badness. W is for wheat, a reminder of her doomed relationship with a man who strictly avoided gluten; X is for xylitol, whose structure links to her stepdaughter’s belief in the power of crystals.

Health is a recurring element that intersects with eating habits: Lebo has ulcerative colitis, depression and allergies; her grandfather was a pharmacist and her mother is a physical therapist who suffers from migraines and is always trying out different diets. The extent to which a fruit can genuinely promote wellness is a question that is pondered more than once. Whether the main focus is on the foodstuff or the family experience, each piece is carefully researched so as to be authoritative yet conversational. The author is particularly good at describing smells and tastes, which can be so difficult to translate into words:

My first taste of durian was as candy, a beige lozenge with a slight pink blush that my boss at the time dared me to try. … It tasted of strawberries and old garlic. I had to will myself to finish. … My second taste of durian was at dim sum in New York City, visiting a man who would never love me. The durian was stewed, sweetened, and crenellated with flaky dough. … [It] was like peaches laced with onions, and had a richness that made my chest tight. Each bite was a dare. Could I keep going?

A single medlar that has been bletted outdoors through early December can be eaten in three bites. The first taste will be of spiced applesauce. … The second taste, because the medlar has spent long cold weeks on the branch, is sparkling wine. Not a good sparkling wine, but pleasant enough. Slightly explosive-tasting, like certain manufactured candies. Ugly, but what a personality. The third taste is a cold mildew one usually only smells, and generally interprets as a warning not to eat any more. You have now finished the medlar.

Two essays in a row best exemplified the book’s approach for me. The chapter on gooseberries, the cover stars, captures everything I love about them (we have two bushes; this year we turned our haul into a couple of Nigel Slater’s crumble cakes and a batch of gingery jam) and gives tips on preparation plus recipes I could see myself making. “Gooseberries are sour like you’ve arrived before they were ready for company, like they wanted you to see them in a better dress,” Lebo writes. The piece on huckleberries then shares Indigenous (Salish) wisdom about the fruit and notes that in a Spokane McDonald’s you can buy a huckleberry shake.

Over the eight months I spent with this collection – picking it up once in a while to read an essay, or a portion of one – I absorbed a lot of information, as well as some ideas for dishes I might actually try. Most of all, I admired how this book manages to be about everything, which makes sense because food is not just central to our continued survival but also bound up with collective and personal identity, memory, and traditions. Though it started off slightly scattershot for me, it’s ended up being one of my favorite reading experiences of the year.

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

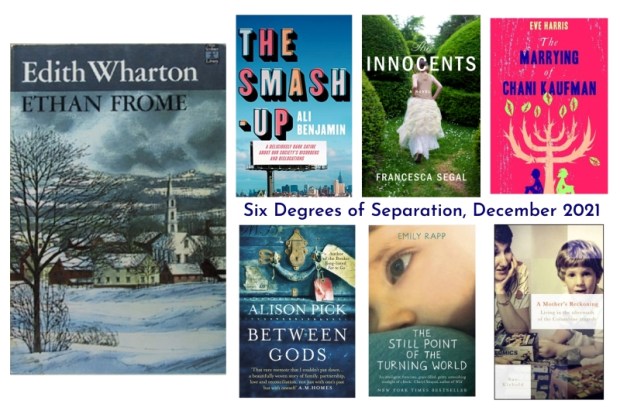

Six Degrees: Ethan Frome to A Mother’s Reckoning

This month we began with Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton, which was our buddy read for the short classics week of Novellas in November. I reread and reviewed it recently. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 When I posted an excerpt of my Ethan Frome review on Instagram, I got a comment from the publicist who was involved with the recent UK release of The Smash-Up by Ali Benjamin, a modern update of Wharton’s plot. Here’s part of the blurb: “Life for Ethan and Zo used to be simple. Ethan co-founded a lucrative media start-up, and Zo was well on her way to becoming a successful filmmaker. Then they moved to a rural community for a little more tranquility—or so they thought. … Enter a houseguest who is young, fun, and not at all concerned with the real world, and Ethan is abruptly forced to question everything: his past, his future, his marriage, and what he values most.” I’m going to try to get hold of a review copy when the paperback comes out in February.

#1 When I posted an excerpt of my Ethan Frome review on Instagram, I got a comment from the publicist who was involved with the recent UK release of The Smash-Up by Ali Benjamin, a modern update of Wharton’s plot. Here’s part of the blurb: “Life for Ethan and Zo used to be simple. Ethan co-founded a lucrative media start-up, and Zo was well on her way to becoming a successful filmmaker. Then they moved to a rural community for a little more tranquility—or so they thought. … Enter a houseguest who is young, fun, and not at all concerned with the real world, and Ethan is abruptly forced to question everything: his past, his future, his marriage, and what he values most.” I’m going to try to get hold of a review copy when the paperback comes out in February.

#2 One of my all-time favourite debut novels is The Innocents by Francesca Segal, which won the Costa First Novel Award in 2012. It is also a contemporary reworking of an Edith Wharton novel, this time The Age of Innocence. Segal’s love triangle, set in a world I know very little about (the tight-knit Jewish community of northwest London), stays true to the emotional content of the original: the interplay of love and desire, jealousy and frustration. Adam Newman has been happily paired with Rachel Gilbert for nearly 12 years. Now engaged, Adam and Rachel seem set to become pillars of the community. Suddenly, their future is threatened by the return of Rachel’s bad-girl American cousin, Ellie Schneider.

#2 One of my all-time favourite debut novels is The Innocents by Francesca Segal, which won the Costa First Novel Award in 2012. It is also a contemporary reworking of an Edith Wharton novel, this time The Age of Innocence. Segal’s love triangle, set in a world I know very little about (the tight-knit Jewish community of northwest London), stays true to the emotional content of the original: the interplay of love and desire, jealousy and frustration. Adam Newman has been happily paired with Rachel Gilbert for nearly 12 years. Now engaged, Adam and Rachel seem set to become pillars of the community. Suddenly, their future is threatened by the return of Rachel’s bad-girl American cousin, Ellie Schneider.

#3 Also set in north London’s Jewish community is The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Chani is the fifth of eight daughters in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Golders Green. The story begins and closes with Chani and Baruch’s wedding ceremony, and in between it loops back to detail their six-month courtship and highlight a few events from their family past. It’s a light-hearted, gossipy tale of interclass matchmaking in the Jane Austen vein.

#3 Also set in north London’s Jewish community is The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Chani is the fifth of eight daughters in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Golders Green. The story begins and closes with Chani and Baruch’s wedding ceremony, and in between it loops back to detail their six-month courtship and highlight a few events from their family past. It’s a light-hearted, gossipy tale of interclass matchmaking in the Jane Austen vein.

#4 I learned more about Jewish beliefs and rituals via several memoirs, including Between Gods by Alison Pick. Her paternal grandparents escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Holocaust; she only found out that her father was Jewish through eavesdropping. In 2008 the author (a Toronto-based novelist and poet) decided to convert to Judaism. The book vividly depicts a time of tremendous change, covering a lot of other issues Pick was dealing with simultaneously, such as depression, preparation for marriage, pregnancy, and so on.

#4 I learned more about Jewish beliefs and rituals via several memoirs, including Between Gods by Alison Pick. Her paternal grandparents escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Holocaust; she only found out that her father was Jewish through eavesdropping. In 2008 the author (a Toronto-based novelist and poet) decided to convert to Judaism. The book vividly depicts a time of tremendous change, covering a lot of other issues Pick was dealing with simultaneously, such as depression, preparation for marriage, pregnancy, and so on.

#5 One small element of Pick’s story was her decision to be tested for the BRCA gene because it’s common among Ashkenazi Jews. Tay-Sachs disease is usually found among Ashkenazi Jews, but because only her husband was Jewish, Emily Rapp never thought to be tested before she became pregnant with her son Ronan. Had she known she was also a carrier, things might have gone differently. The Still Point of the Turning World was written while her young son was still alive, but terminally ill.

#5 One small element of Pick’s story was her decision to be tested for the BRCA gene because it’s common among Ashkenazi Jews. Tay-Sachs disease is usually found among Ashkenazi Jews, but because only her husband was Jewish, Emily Rapp never thought to be tested before she became pregnant with her son Ronan. Had she known she was also a carrier, things might have gone differently. The Still Point of the Turning World was written while her young son was still alive, but terminally ill.

#6 Another wrenching memoir of losing a son: A Mother’s Reckoning by Sue Klebold, whose son Dylan was one of the Columbine school shooters. I was in high school myself at the time, and the event made a deep impression on me. Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is Klebold’s determination to reclaim Columbine as a murder–suicide and encourage mental health awareness; all author proceeds were donated to suicide prevention and mental health charities. There’s no real redemptive arc, though, no easy answers; just regrets. If something similar could happen to any family, no one is immune. And Columbine was only one of many major shootings. I finished this feeling spent, even desolate. Yet this is a vital book everyone should read.

#6 Another wrenching memoir of losing a son: A Mother’s Reckoning by Sue Klebold, whose son Dylan was one of the Columbine school shooters. I was in high school myself at the time, and the event made a deep impression on me. Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is Klebold’s determination to reclaim Columbine as a murder–suicide and encourage mental health awareness; all author proceeds were donated to suicide prevention and mental health charities. There’s no real redemptive arc, though, no easy answers; just regrets. If something similar could happen to any family, no one is immune. And Columbine was only one of many major shootings. I finished this feeling spent, even desolate. Yet this is a vital book everyone should read.

So, I’ve gone from one unremittingly bleak book to another, via sex, religion and death. Nothing for cheerful holiday reading – or a polite dinner party conversation – here! All my selections were by women this month.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Next month’s starting point is Rules of Civility by Amor Towles; I have a copy on the shelf and this would be a good excuse to read it!

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Novellas in November Wrap-Up

Last year, our first of hosting Novellas in November as an official blogger challenge, we had 89 posts by 30 bloggers. This year, Cathy and I have been simply blown away by the level of participation: as of this afternoon, our count is that 49 bloggers have taken part, publishing just over 200 posts and covering over 270 books. We’ve done our best to keep up with the posts, which we’ve each been collecting as links on the opening master post. (Here’s mine.)

Thank you all for being so engaged with #NovNov, including with the buddy reads we tried out for the first time this year. We’re already thinking about changes we might implement for next year.

A special mention goes to Simon of Stuck in a Book for being such a star supporter and managing to review a novella on most days of the month.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Some authors who were reviewed more than once (highlighting different works) were Margaret Atwood, Henry James, Elizabeth Jolley, Amos Oz, George Simenon, and Muriel Spark.

Of course, novellas are great to read the whole year round and not just in November, but we hope this has been a good excuse to pick up some short books and appreciate how much can be achieved with such a limited number of pages. If we missed any of your coverage, let us know and we will gladly add it in to the master list.

See you next year!

Love Your Library, November 2021

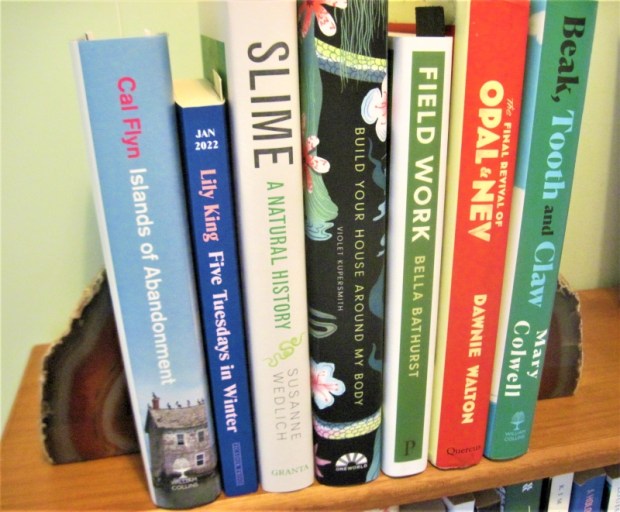

It’s the second month of the new Love Your Library feature.

I’d like to start out by thanking all those who have taken part since last month’s post:

Adrian shared lovely stories about the libraries he’s used in Ireland, from childhood onwards.

Laila, Lori and Margaret highlighted their recent loans and reads.

Laura sent a photo of her shiny new library copy of Sally Rooney’s latest novel.

Finally, Marcie contributed this TikTok video of her library stacks!

As for my recent library experiences…

A stand-out read:

The Performance by Claire Thomas: What a terrific setup: three women are in a Melbourne theatre watching a performance of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days. Margot is a veteran professor whose husband is developing dementia. Ivy is a new mother whose wealth hardly makes up for the devastating losses of her earlier life. Summer is a mixed-race usher concerned about her girlfriend during the fires rampaging outside the city. In rotating close third person sections, Thomas takes us into these characters’ inner worlds, contrasting their personal worries with wider issues of women’s and indigenous people’s rights and the environmental crisis, as well as with the increasingly claustrophobic scene on stage. In “The Interval,” written as a script, the main characters interact with each other, with the “forced intimacy between strangers” creating opportunities for chance meetings and fateful decisions.

The Performance by Claire Thomas: What a terrific setup: three women are in a Melbourne theatre watching a performance of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days. Margot is a veteran professor whose husband is developing dementia. Ivy is a new mother whose wealth hardly makes up for the devastating losses of her earlier life. Summer is a mixed-race usher concerned about her girlfriend during the fires rampaging outside the city. In rotating close third person sections, Thomas takes us into these characters’ inner worlds, contrasting their personal worries with wider issues of women’s and indigenous people’s rights and the environmental crisis, as well as with the increasingly claustrophobic scene on stage. In “The Interval,” written as a script, the main characters interact with each other, with the “forced intimacy between strangers” creating opportunities for chance meetings and fateful decisions.

Doorstoppers: A problem

Aware that I’m heading to the States for Christmas on the 14th of December (only a couple of weeks from now!), I’ve started culling my library stacks, returning any books that I’m not super-keen to read before the end of the year. A few I’ll borrow another time, but most I decided weren’t actually for me, even if raved about elsewhere.

I mentioned in a post last week that I’ve had a hard time finding the concentration for doorstoppers lately, which is ironic giving how many high-profile ones there have been this year – or even just this autumn. (For example, seven of BookPage’s top 20 fiction releases of 2021 are over 450 pages.) I gave up twice on Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead, swiftly abandoned Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr (a silly bookish attempt at something like Cloud Atlas), didn’t have time to attempt Tenderness by Alison Macleod and The Magician by Colm Tóibín, and recently returned The Morning Star by Karl Ove Knausgaard unread.

Why so many chunky reads this year, and this season in particular? I’ve wondered if it has had something to do with the lockdown mentality – for authors or readers, or both. It can be awfully cozy, especially as winter advances (in this hemisphere), to sink into a big book. But I find that I’m always looking for an excuse to not engage with a doorstopper.

I generally enjoy the scope, detail and moral commentary of Jonathan Franzen’s novels; his previous two, Freedom and Purity, which also numbered 500+ pages, were fantastic. But Crossroads wasn’t happening for me, at least not right now. I only got to page 23 on this attempt. The Chicago setting was promising, and I’m there for the doubt and hypocrisy of church-bound characters. But with text this dense, it feels like it takes SO MANY WORDS to convey just one scene or conversation. I was finding the prose a little obnoxious, too, e.g.

I generally enjoy the scope, detail and moral commentary of Jonathan Franzen’s novels; his previous two, Freedom and Purity, which also numbered 500+ pages, were fantastic. But Crossroads wasn’t happening for me, at least not right now. I only got to page 23 on this attempt. The Chicago setting was promising, and I’m there for the doubt and hypocrisy of church-bound characters. But with text this dense, it feels like it takes SO MANY WORDS to convey just one scene or conversation. I was finding the prose a little obnoxious, too, e.g.

Of Santa the Hildebrandts had always said, Bah, humbug. And yet somehow, long past the age of understanding that presents don’t just buy and wrap themselves, he’d accepted their sudden annual appearance as, if not a miraculous provision, then a phenomenon like his bladder filling with urine, part of the normal course of things. How had he not grasped at nine a truth so obvious to him at ten? The epistemological disjunction was absolute.

Problems here: How many extra words do you need to say “He stopped believing in Santa at age 10”? When is the phrase “epistemological disjunction” ever anything other than showing off? And why did micturition present itself as an apt metaphor?

But anyway, I’ve hardly given this a fair shake yet. I daresay I’ll read it another time; it’ll be my eighth book by Franzen.

Do share a link to your own post in the comments, and feel free to use the above image. I’ve co-opted a hashtag that is already popular on Twitter and Instagram: #LoveYourLibrary.

Here’s a reminder of my ideas of what you might choose to post (this list will stay up on the project page):

- Photos or a list of your latest library book haul

- An account of a visit to a new-to-you library

- Full-length or mini reviews of some recent library reads

- A description of a particular feature of your local library

- A screenshot of the state of play of your online account

- An opinion piece about library policies (e.g. Covid procedures or fines amnesties)

- A write-up of a library event you attended, such as an author reading or book club.

If it’s related to libraries, I want to hear about it!

The Blind Assassin Reread for #MARM, and Other Doorstoppers

It’s the fourth annual Margaret Atwood Reading Month (#MARM), hosted by Canadian blogger extraordinaire Marcie of Buried in Print. In previous years, I’ve read Surfacing and The Edible Woman, The Robber Bride and Moral Disorder, and Wilderness Tips. This year Laila at Big Reading Life and I did a buddy reread of The Blind Assassin, which was historically my favourite Atwood novel. I’d picked up a free paperback the last time I was at The Book Thing of Baltimore. Below are some quick thoughts based on what I shared with Laila as I was reading.

The Blind Assassin (2000)

Winner of the Booker Prize and Hammett Prize; shortlisted for the Orange Prize

I must have first read this about 13 years ago. The only thing I remembered before I started my reread was that there is a science fiction book-within-the-book. I couldn’t recall anything else about the setup before I read in the blurb about the suspicious circumstances of Laura’s death in 1945. Indeed, the opening line, which deserves to be famous, is “Ten days after the war ended, my sister Laura drove a car off a bridge.”

I always love novels about sisters, and Iris is a terrific narrator. Now a cantankerous elderly woman, she takes us back through her family history: her father’s button factory and his clashes with organizing workers, her mother’s early death, and her enduring relationship with their housekeeper, Reenie. Iris and Laura met a young man named Alex Thomas, a war orphan with radical views, at the factory’s Labour Day picnic, and it was clear early on that Laura was smitten, while Iris went on to marry Richard Griffen, a nouveau riche industrialist.

Interspersed with Iris’s recollections are newspaper articles that give a sense that the Chase family might be cursed, and excerpts from The Blind Assassin, Laura’s posthumously published novel. Daring for its time in terms of both explicit content and literary form (e.g., no speech marks), it has a storyline rather similar to 1984, with an upper-crust woman having trysts with a working-class man in his squalid lodgings. During their time snatched together, he also tells her a story inspired by the pulp sci-fi of the time. I was less engaged by the story-within-the-story(-within-the-story) this time around compared to Iris’s current life and flashbacks.

In the back of my mind, I had a vague notion that there was a twist coming, and in my impatience to see if I was right I ended up skimming much of the second half of the novel. My hunch was proven correct, but I was disappointed with myself that I wasn’t able to enjoy the journey more a second time around. Overall, this didn’t wow me on a reread, but then again, I am less dazzled by literary “tricks” these days. At the sentence level, however, the writing was fantastic, including descriptions of places, seasons and characters’ psychology. It’s intriguing to think about whether we can ever truly know Laura given Iris’s guardianship of her literary legacy.

If you haven’t read this before, find a time when you can give it your full attention and sink right in. It’s so wise on family secrets and the workings of memory and celebrity, and the weaving in of storylines in preparation for the big reveal is masterful.

Some favourite passages:

“What fabrications they are, mothers. Scarecrows, wax dolls for us to stick pins into, crude diagrams. We deny them an existence of their own, we make them up to suit ourselves – our own hungers, our own wishes, our own deficiencies.”

“Beginnings are sudden, but also insidious. They creep up on you sideways, they keep to the shadows, they lurk unrecognized. Then, later, they spring.”

“The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read. Not by any other person, and not even by yourself at some later date. Otherwise you begin excusing yourself. You must see the writing as emerging like a long scroll of ink from the index finger of your right hand; you must see your left hand erasing it. Impossible, of course.”

My original rating (c. 2008):

My rating now:

What to read for #MARM next year, I wonder??

In general, I have been struggling mightily with doorstoppers this year. I just don’t seem to have the necessary concentration, so Novellas in November has been a boon. I’ve been battling with Ruth Ozeki’s latest novel for months, and another attempted buddy read of 460 pages has also gone by the wayside. I’ll write a bit more on this for #LoveYourLibrary on Monday, including a couple of recent DNFs. The Blind Assassin was only my third successful doorstopper of the year so far. After The Absolute Book, the other one was:

The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

In Towles’ third novel – a big, old-fashioned dose of Americana – brothers and pals set out from Nebraska on road and rail adventures to find a fortune in 1950s New York. The book features some fantastic characters. Precocious Billy steals every scene he appears in. Duchess is a delightfully flamboyant bounder, peppering his speech with malapropisms and Shakespeare quotes. However, Emmett is a dull protagonist, and it’s disappointing that Sally, one of just two main female characters, plays such a minor role. A danger with an episodic narrative is that random events and encounters pile up but don’t do much to further the plot. At nearly 200 pages in, I realized little of consequence had happened yet. A long road, then, with some ups and downs along the way, but Towles’ fans will certainly want to sign up for the ride.

See my full review for BookBrowse; see also my related article on Studebaker cars.

With thanks to Hutchinson for the free copy for review.

Katerina Canyon is from Los Angeles and now lives in Seattle. This is her second collection. As the poem “Involuntary Endurance” makes clear, you survive an upbringing like hers only because you have to. This autobiographical collection is designed to earn the epithet “unflinching,” with topics including domestic violence, parental drug abuse, and homelessness. When you hear that her father once handcuffed and whipped her autistic brother, you understand why “No More Poems about My Father” ends up breaking its title’s New Year’s resolution!

Katerina Canyon is from Los Angeles and now lives in Seattle. This is her second collection. As the poem “Involuntary Endurance” makes clear, you survive an upbringing like hers only because you have to. This autobiographical collection is designed to earn the epithet “unflinching,” with topics including domestic violence, parental drug abuse, and homelessness. When you hear that her father once handcuffed and whipped her autistic brother, you understand why “No More Poems about My Father” ends up breaking its title’s New Year’s resolution! I was a huge fan of Edward Carey’s

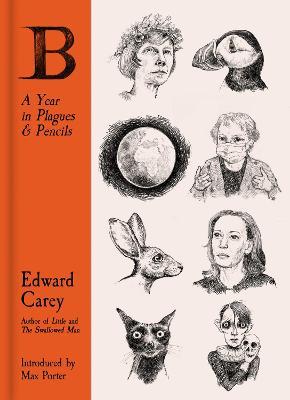

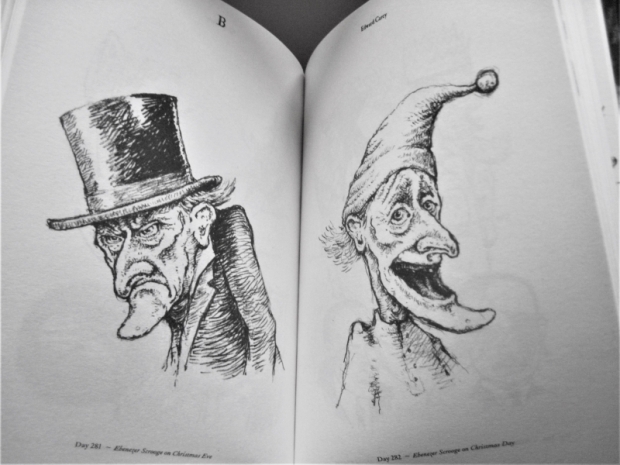

I was a huge fan of Edward Carey’s

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed

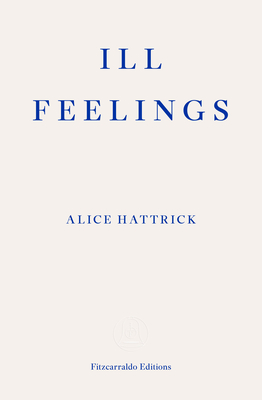

After a fall landed her in hospital with a cracked skull, Abbs couldn’t wait to roam again and vowed all her future holidays would be walking ones. What time she had for pleasure reading while raising children was devoted to travel books; looking at her stacks, she realized they were all by men. Her challenge to self was to find the women and recreate their journeys. I was drawn to this because I’d enjoyed  “My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,

“My mother and I have symptoms of illness without any known cause,” Hattrick writes. When they showed signs of the ME/CFS their mother had suffered from since 1995, it was assumed there was imitation going on – that a “shared hysterical language” was fuelling their continued infirmity. It didn’t help that both looked well, so could pass as normal despite debilitating fatigue. Into their own family’s story, Hattrick weaves the lives and writings of chronically ill women such as Elizabeth Barrett Browning (see my review of Fiona Sampson’s biography,  I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,

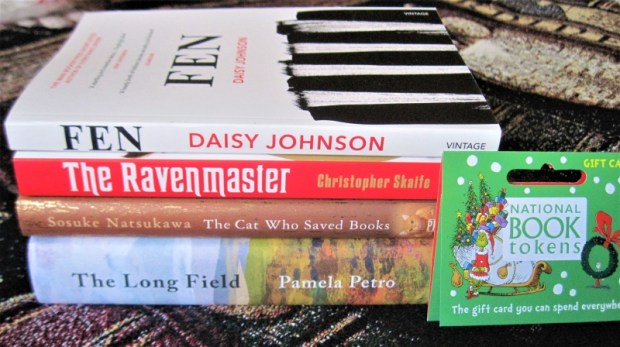

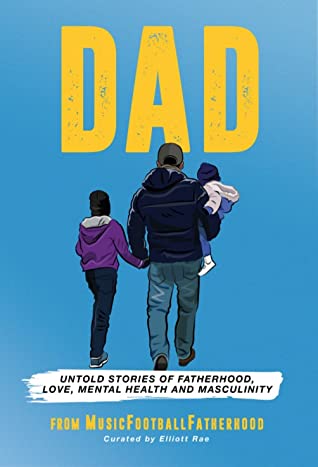

I loved Powles’s bite-size food memoir,  Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on

Music.Football.Fatherhood, a British equivalent of Mumsnet, brings dads together in conversation. These 20 essays by ordinary fathers run the gamut of parenting experiences: postnatal depression, divorce, single parenthood, a child with autism, and much more. We’re used to childbirth being talked about by women, but rarely by their partners, especially things like miscarriage, stillbirth and trauma. I’ve already written on  Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in

Santhouse is a consultant psychiatrist at London’s Guy’s and Maudsley hospitals. This book was an interesting follow-up to Ill Feelings (above) in that the author draws an important distinction between illness as a subjective experience and disease as an objective medical reality. Like Abdul-Ghaaliq Lalkhen does in  I reviewed

I reviewed  A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)

A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)  This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed  A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s  After reviewing Josipovici’s

After reviewing Josipovici’s  Otsuka’s

Otsuka’s