Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau (Blog Tour)

Are you having a groovy June yet? If not, I have just the remedy: a juicy coming-of-age novel that drops you directly into the Baltimore summer of 1975. Mary Jane Dillard, 14, lives in the upper-class white neighborhood of Roland Park. Her parents are prim types who attend church every week, belong to a country club, and pray for the (Republican) president’s health before each sit-down family dinner. When Mary Jane starts working as a daytime nanny for five-year-old Izzy, the Cones’ way of life is a revelation to her. They are messy bohemians who think nothing of walking around the house half-naked, shouting up and down the stairs at each other, or leaving a fridge full of groceries to rot and going out for fast food instead.

Dr. Cone is a psychiatrist whose top-secret assignment is helping a rock star to kick his drug addiction. Jimmy and his actress wife, Sheba, move into the Cones’ attic for the summer. If they go out in public, they wear wigs and pretend to be friends visiting from Rhode Island. While the Cones are busy monitoring or trying to imitate their celebrity guests, Mary Jane introduces discipline by cleaning the kitchen, alphabetizing the bookcase, and replicating her mother’s careful weekly menus with food she buys from Eddie’s market. In some ways she seems the most responsible member of the household, but in others she’s painfully naïve, entirely ignorant of sex and unaware that her name is a slang term for marijuana.

Dr. Cone is a psychiatrist whose top-secret assignment is helping a rock star to kick his drug addiction. Jimmy and his actress wife, Sheba, move into the Cones’ attic for the summer. If they go out in public, they wear wigs and pretend to be friends visiting from Rhode Island. While the Cones are busy monitoring or trying to imitate their celebrity guests, Mary Jane introduces discipline by cleaning the kitchen, alphabetizing the bookcase, and replicating her mother’s careful weekly menus with food she buys from Eddie’s market. In some ways she seems the most responsible member of the household, but in others she’s painfully naïve, entirely ignorant of sex and unaware that her name is a slang term for marijuana.

Open marriage, sex addiction and group therapy are new concepts that soon become routine for our confiding narrator, as she adopts a ‘What they don’t know can’t hurt them’ stance towards her trusting parents. Blau is the author of four previous YA novels, and while this is geared towards adults, it resonates for how it captures the uncertainty and swirling hormones of the teenage years. Who didn’t share Mary Jane’s desperate curiosity to learn about sex? Who can’t remember a moment of realization that parents aren’t right about everything?

Music runs all through the book, creating and cementing bonds between the characters. Mary Jane sings in the choir and shares her mother’s love of both church music and show tunes. Jimmy and Sheba are always making up little songs on which Mary Jane harmonizes, and a clandestine trip to a record store in an African American part of town forms one of the novel’s pivotal scenes. The relationship between Mary Jane and Izzy, who is precocious and always coming out with malapropisms, is touching, and Blau cleverly inserts references to the casual racism and antisemitism of the 1970s.

I love it when a novel has a limited setting and can evoke a sense of wistfulness for a golden time that will never come again. I highly recommend this for nostalgic summer reading, particularly if you’ve enjoyed work by Curtis Sittenfeld – especially Prep and Rodham.

My thanks to Harper360 UK and Anne Cater for arranging my proof copy for review.

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for Mary Jane. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Library Checkout, May 2021

Another big library reading month for me as I scrambled to get through the books that were reserved after me and then wrangle the remaining pile under some semblance of control before heading back to the USA for my mother’s wedding. I’ve also suspended any holds that look like they might arrive imminently – the first time I’ve taken advantage of this option. Once I’m back I’m sure I’ll quickly build up another goodly stack to last me through the summer.

I give links to reviews of books I haven’t already featured here, as well as ratings for most reads and skims. I would be delighted to have other bloggers – not just book bloggers – join in with this meme. Feel free to use the image above and leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part in Library Checkout (on the last Monday of each month), or tag me on Twitter and Instagram: @bookishbeck / #TheLibraryCheckout & #LoveYourLibraries.

READ

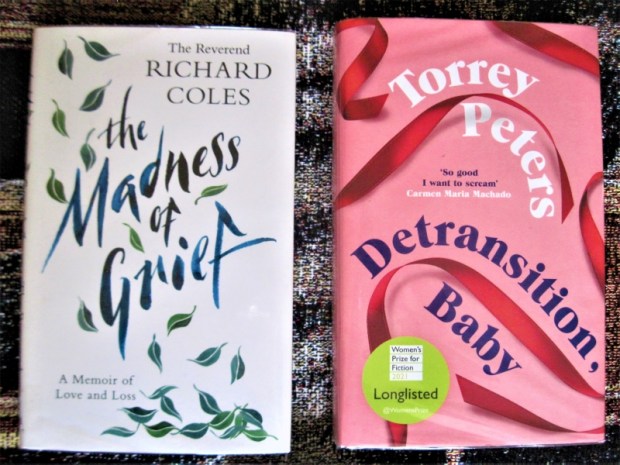

- The Madness of Grief: A Memoir of Love and Loss by Reverend Richard Coles

- Ten Days by Austin Duffy

- Featherhood: On Birds and Fathers by Charlie Gilmour

- Deep Water by Patricia Highsmith

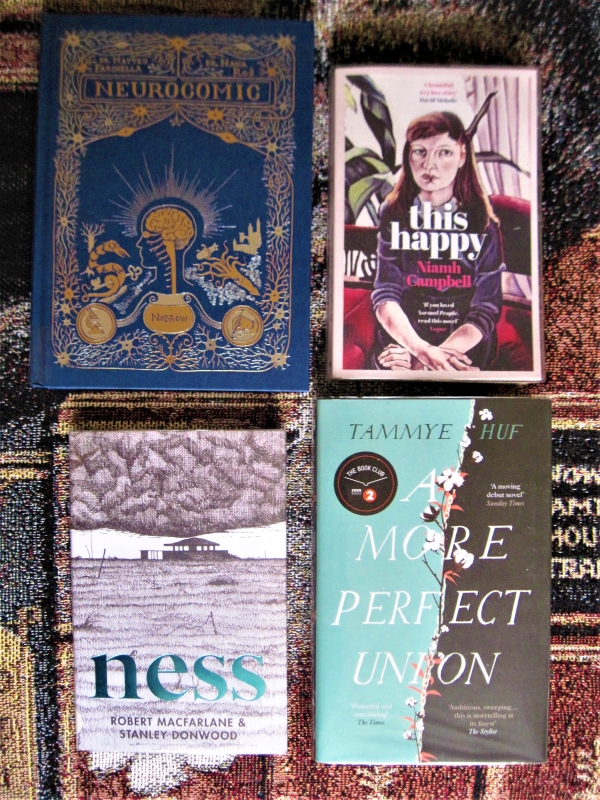

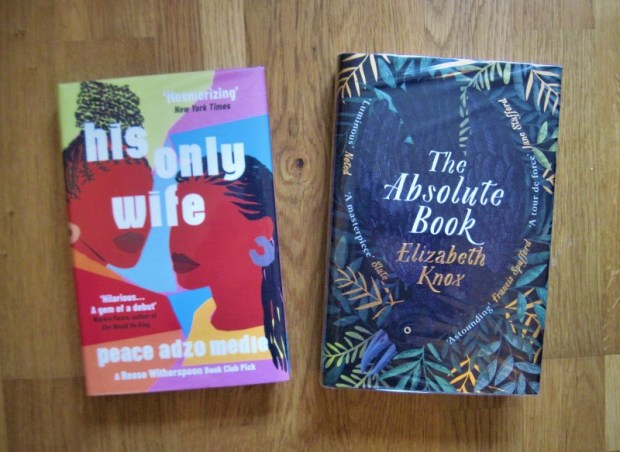

- The Absolute Book by Elizabeth Knox

- Ness by Robert Macfarlane and Stanley Donwood

- The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by Brian Moore

- The Pleasure Steamers by Andrew Motion

- You’re Not Listening: What You’re Missing and Why It Matters by Kate Murphy

- Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson

- Woods etc. by Alice Oswald

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

- Neurocomic by Dr. Matteo Farinella (illustrations) and Dr. Hana Roš

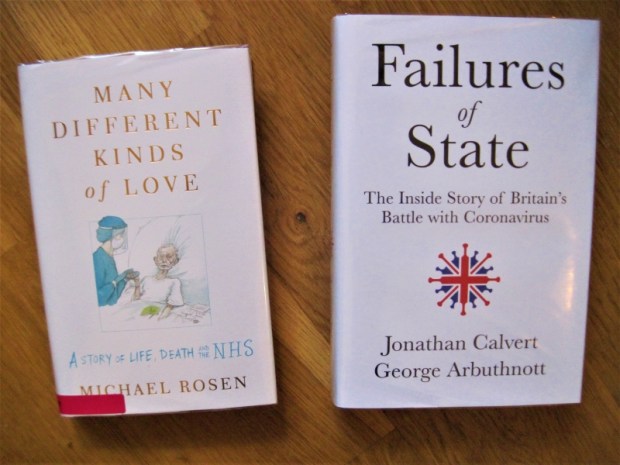

- Many Different Kinds of Love: A Story of Life, Death and the NHS by Michael Rosen

- When We Went Wild by Isabella Tree and Allira Tee (a children’s picture book; doesn’t count towards my year total)

SKIMMED

- After: A Doctor Explores What Near-Death Experiences Reveal about Life and Beyond by Bruce Greyson

- The Ministry of Bodies: Life and Death in a Modern Hospital by Seamus O’Mahony

CURRENTLY READING

- Blue Dog by Louis de Bernières

- Becoming a Man: Half a Life Story by Paul Monette [set aside temporarily]

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Under the Blue by Oana Aristide

- Summer Story and Autumn Story by Jill Barklem

- This Happy by Niamh Campbell

- The Pure Gold Baby by Margaret Drabble

- Lakewood by Megan Giddings

- The Master Bedroom by Tessa Hadley

- A More Perfect Union by Tammye Huf

- The Rome Plague Diaries: Lockdown Life in the Eternal City by Matthew Kneale

- His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

- Dreamland by Rosa Rankin-Gee

- How to Be Sad: Everything I’ve Learned about Getting Happier, by Being Sad, Better by Helen Russell

- Earthed: A Memoir by Rebecca Schiller

- The Color Purple by Alice Walker (to reread)

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Who Is Maud Dixon? by Alexandra Andrews

- Misplaced Persons by Susan Beale

- Civilisations by Laurent Binet

- Medusa’s Ankles: Selected Stories by A.S. Byatt

- Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers

- Heavy Light: A Journey through Madness, Mania and Healing by Horatio Clare

- Second Place by Rachel Cusk

- Darwin’s Dragons by Lindsay Galvin

- Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny

- The Premonition: A Pandemic Story by Michael Lewis

- Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon

- Circus of Wonders by Elizabeth Macneal

- Demystifying the Female Brain by Sarah McKay

- When the Stars Go Dark by Paula McLain

- Elegy for a River: Whiskers, Claws and Conservation’s Last, Wild Hope by Tom Moorhouse

- Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

- Heartstoppers, Volume 1 by Alice Oseman

- Joe Biden: American Dreamer by Evan Osnos

- The Dig by John Preston

- My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

- I Belong Here: A Journey along the Backbone of Britain by Anita Sethi

- Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

- Broke Vegan: Over 100 Plant-Based Recipes that Don’t Cost the Earth by Saskia Sidey

- Still Life by Sarah Winman

- The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

- The Last Migration by Charlotte McConaghy – I read the first 22 pages. The plot felt very similar to Ankomst and I didn’t get drawn in by the prose, but this has been a huge word-of-mouth hit among my Goodreads friends. I’ll try it again another time.

- Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley

RETURNED UNREAD

- Failures of State: The Inside Story of Britain’s Battle with Coronavirus by Jonathan Calvert and George Arbuthnott – I think I’m finally tiring of Covid stories.

- Life Support: Diary of an ICU Doctor on the Frontline of the COVID Crisis by Jim Down – Ditto, though having now seen him at a Hay Festival event I might give this a try another time.

- Life Sentences by Billy O’Callaghan – I can’t even remember how I heard about this or why I put a request on it!

What appeals from my stacks?

Recommended May Releases: Adichie, Pavey and Unsworth

Three very different works of women’s life writing: heartfelt remarks on bereavement, a seasonal diary of stewarding four wooded acres in Somerset, and a look back at postnatal depression.

Notes on Grief by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

This slim hardback is an expanded version of an essay Adichie published in the New Yorker in the wake of her father’s death in June 2020. With her large family split across three continents and coronavirus lockdown precluding in-person get-togethers, they had a habit of frequent video calls. She had seen her father the day before on Zoom and knew he was feeling unwell and in need of rest, but the news of his death still came as a complete shock.

Adichie anticipates all the unhelpful platitudes people could and did send her way: he lived to a ripe old age (he was 88), he had a full life and was well respected (he was Nigeria’s first statistics professor), he had a mercifully swift end (kidney failure). Her logical mind knows all of these facts, and her writer’s imagination has depicted grief many times. Still, this loss blindsided her.

Adichie anticipates all the unhelpful platitudes people could and did send her way: he lived to a ripe old age (he was 88), he had a full life and was well respected (he was Nigeria’s first statistics professor), he had a mercifully swift end (kidney failure). Her logical mind knows all of these facts, and her writer’s imagination has depicted grief many times. Still, this loss blindsided her.

She’d always been a daddy’s girl, but the anecdotes she tells confirm how special he was: wise and unassuming; a liberal Catholic suspicious of materialism and with a dry humour. I marvelled at one such story: in 2015 he was kidnapped and held in the boot of a car for three days, his captors demanding a ransom from his famous daughter. What did he do? Correct their pronunciation of her name, and contradict them when they said that clearly his children didn’t love him. “Grief has, as one of its many egregious components, the onset of doubt. No, I am not imagining it. Yes, my father truly was lovely.” With her love of fashion, one way she dealt with her grief was by designing T-shirts with her father’s initials and the Igbo words for “her father’s daughter” on them.

I’ve read many a full-length bereavement memoir, and one might think there’s nothing new to say, but Adichie writes with a novelist’s eye for telling details and individual personalities. She has rapidly become one of my favourite authors: I binged on most of her oeuvre last year and now have just one more to read, Purple Hibiscus, which will be one of my 20 Books of Summer. I love her richly evocative prose and compassionate outlook, no matter the subject. At £10, this 85-pager is pricey, but I was lucky to get it free with Waterstones loyalty points.

Favourite lines:

“In the face of this inferno that is sorrow, I am callow and unformed.”

“How is it that the world keeps going, breathing in and out unchanged, while in my soul there is a permanent scattering?”

Deeper Into the Wood by Ruth Pavey

In 1999 Ruth Pavey bought four acres of scrubland at auction, happy to be returning to her family’s roots in the Somerset Levels and hoping to work alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. Her account of the first two decades of this ongoing project, A Wood of One’s Own, was published in 2017.

In 1999 Ruth Pavey bought four acres of scrubland at auction, happy to be returning to her family’s roots in the Somerset Levels and hoping to work alongside nature to restore some of her land to orchard and maintain the rest in good health. Her account of the first two decades of this ongoing project, A Wood of One’s Own, was published in 2017.

In this sequel, she gives peaceful snapshots of the wood throughout 2019, from first snowdrops to final apple pressing, but also faces up to the environmental degradation that is visible even in this pocket of the countryside. “I am sure there has been a falling off in numbers of insects, smaller birds and rabbits on my patch,” she insists. Without baseline data, it is hard to support this intuition, but she has botanical and bird surveys done, and invites an expert in to do a moth-trapping evening. The resulting species lists are included as appendices. In addition, Pavey weaves a backstory for her land. She meets a daffodil breeder, investigates the source of her groundwater, and visits the head gardener at the Bishop’s Palace in Wells, where her American black walnut sapling came from. She also researches the Sugg family, associated with the land (“Sugg’s Orchard” on the deed) from the 1720s.

Pavey aims to treat this landscape holistically: using sheep to retain open areas instead of mowing the grass, and weighing up the benefits of the non-native species she has planted. She knows her efforts can only achieve so much; the pesticides standard to industrial-scale farming may still be reaching her trees on the wind, though she doesn’t apply them herself. “One sad aspect of worrying about the state of the natural world is that everything starts to look wrong,” she admits. Starting in that year’s abnormally warm January, it was easy for her to assume that the seasons can no longer be relied on.

Pavey aims to treat this landscape holistically: using sheep to retain open areas instead of mowing the grass, and weighing up the benefits of the non-native species she has planted. She knows her efforts can only achieve so much; the pesticides standard to industrial-scale farming may still be reaching her trees on the wind, though she doesn’t apply them herself. “One sad aspect of worrying about the state of the natural world is that everything starts to look wrong,” she admits. Starting in that year’s abnormally warm January, it was easy for her to assume that the seasons can no longer be relied on.

Compared with her first memoir, this one is marked by its intellectual engagement with the principles and practicalities of rewilding. Clearly, her inner struggle is motivated less by the sense of ownership than by the call of stewardship. While this book is likely be of most interest to those with a local connection or a similar project underway, it offers a universal model of how to mitigate our environmental impact. Pavey’s black-and-white sketches of the flora and fauna on her patch, reminiscent of Quentin Blake, are a highlight.

With thanks to Duckworth for the proof copy for review. The book will be published tomorrow, the 27th of May.

After the Storm: Postnatal Depression and the Utter Weirdness of New Motherhood by Emma Jane Unsworth

The author’s son was born on the day Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election. Six months later, she realized that she was deep into postnatal depression and finally agreed to get help. The breaking point came when, with her husband* away at a conference, she got frustrated with her son’s constant fussing and pushed him over on the bed. He was absolutely fine, but the guilty what-ifs proliferated, making this a wake-up call for her.

In this succinct, wry and hard-hitting memoir, Unsworth exposes the conspiracies of silence that lead new mothers to lie and pretend that everything is fine. Since her son’s traumatic birth (which I first read about in Dodo Ink’s Trauma anthology), she hadn’t been able to write and was losing her sense of self. To add insult to injury, her baby had teeth at 16 weeks and bit her as he breastfed. She couldn’t even admit her struggles to her fellow mum friends. But “if a woman is in pain for long enough, and denied sleep for long enough, and at the same time feels as though she has to keep going and put a ‘brave’ face on, she’s going to crack.”

In this succinct, wry and hard-hitting memoir, Unsworth exposes the conspiracies of silence that lead new mothers to lie and pretend that everything is fine. Since her son’s traumatic birth (which I first read about in Dodo Ink’s Trauma anthology), she hadn’t been able to write and was losing her sense of self. To add insult to injury, her baby had teeth at 16 weeks and bit her as he breastfed. She couldn’t even admit her struggles to her fellow mum friends. But “if a woman is in pain for long enough, and denied sleep for long enough, and at the same time feels as though she has to keep going and put a ‘brave’ face on, she’s going to crack.”

The book’s titled mini-essays give snapshots into the before and after, but particularly the agonizing middle of things. I especially liked the chapter “The Weirdest Thing I’ve Ever Done in a Hotel Room,” in which she writes about borrowing her American editor’s room to pump breastmilk. Therapy, antidepressants and hiring a baby nurse helped her to ease back into her old life and regain some part of the party girl persona she once exuded – enough so that she was willing to give it all another go (her daughter was born late last year).

While Unsworth mostly writes from experience, she also incorporates recent research and makes bold statements of how cultural norms need to change. “You are not monsters,” she writes to depressed mums. “You need more support. … Motherhood is seismic. It cracks open your life, your relationship, your identity, your body. It features the loss, grief and hardship of any big life change.” I can imagine this being hugely helpful to anyone going through PND (see also my Three on a Theme post on the topic), but I’m not a mother and still found plenty to appreciate (especially “We have to smash the dichotomy of mums/non-mums … being maternal has nothing to do with actually physically being a mother”).

I’m attending a Wellcome Collection online event with Unsworth and midwife Leah Hazard (author of Hard Pushed) this evening and look forward to hearing more from both authors.

*It took me no time at all to identify him from the bare facts: Brighton + doctor + graphic novelist = Ian Williams (author of The Lady Doctor)! I had no idea. What a fun connection.

With thanks to Profile Books/Wellcome Collection for the free copy for review.

This was the nonfiction work of Auster’s I was most keen to read, and I thoroughly enjoyed its first part, “Portrait of an Invisible Man,” which includes a depiction of his late father, a discussion of his relationship with his son, and a brief investigation into his grandmother’s murder of his grandfather, which I’d first learned about from

This was the nonfiction work of Auster’s I was most keen to read, and I thoroughly enjoyed its first part, “Portrait of an Invisible Man,” which includes a depiction of his late father, a discussion of his relationship with his son, and a brief investigation into his grandmother’s murder of his grandfather, which I’d first learned about from  I assumed this was a stand-alone from Knausgaard; when it popped up during an author search on Awesomebooks.com and I saw how short it was, I thought why not? As it happens, this Vintage Minis paperback is actually a set of excerpts from A Man in Love, the second volume of his huge autofiction project, My Struggle (I’ve only read the first book,

I assumed this was a stand-alone from Knausgaard; when it popped up during an author search on Awesomebooks.com and I saw how short it was, I thought why not? As it happens, this Vintage Minis paperback is actually a set of excerpts from A Man in Love, the second volume of his huge autofiction project, My Struggle (I’ve only read the first book,  This was expanded from an occasional series of essays Lewis published in Slate in the 2000s, responding to the births of his three children, Quinn, Dixie and Walker, and exploring the modern father’s role, especially “the persistent and disturbing gap between what I was meant to feel and what I actually felt.” It took time for him to feel more than simply mild affection for each child; often the attachment didn’t arrive until after a period of intense care (as when his son Walker was hospitalized with RSV and he stayed with him around the clock). I can’t seem to find the exact line now, but Jennifer Senior (author of

This was expanded from an occasional series of essays Lewis published in Slate in the 2000s, responding to the births of his three children, Quinn, Dixie and Walker, and exploring the modern father’s role, especially “the persistent and disturbing gap between what I was meant to feel and what I actually felt.” It took time for him to feel more than simply mild affection for each child; often the attachment didn’t arrive until after a period of intense care (as when his son Walker was hospitalized with RSV and he stayed with him around the clock). I can’t seem to find the exact line now, but Jennifer Senior (author of

This was my last remaining unread book by Adichie, and that probably goes a long way toward explaining why I found it underwhelming. In comparison to her two later novels, and even her short stories (of which this reminded me the most), the canvas is small and the emotional scope limited. Kambili is a Nigerian teenager caught between belief systems: her grandfather’s traditional (“pagan”) ancestor worship versus the strict Catholicism that is the preserve of her abusive father, but also of the young priest on whom she has a crush. She and her brother try to stay out of their father’s way, but they are held to such an impossibly high standard of behaviour that it seems inevitable that they will disappoint him.

This was my last remaining unread book by Adichie, and that probably goes a long way toward explaining why I found it underwhelming. In comparison to her two later novels, and even her short stories (of which this reminded me the most), the canvas is small and the emotional scope limited. Kambili is a Nigerian teenager caught between belief systems: her grandfather’s traditional (“pagan”) ancestor worship versus the strict Catholicism that is the preserve of her abusive father, but also of the young priest on whom she has a crush. She and her brother try to stay out of their father’s way, but they are held to such an impossibly high standard of behaviour that it seems inevitable that they will disappoint him. A sweet coming-of-age novella about a boy moving to the Australian Outback to live with his grandfather in the 1960s and adopting a stray dog – a red cloud kelpie, but named Blue. I didn’t realize that this is a prequel (to Red Dog), and based on a screenplay. It was my third book by de Bernières, and it was interesting to read in the afterword that he sees this one as being suited to 12-year-olds, yet most likely to be read by adults.

A sweet coming-of-age novella about a boy moving to the Australian Outback to live with his grandfather in the 1960s and adopting a stray dog – a red cloud kelpie, but named Blue. I didn’t realize that this is a prequel (to Red Dog), and based on a screenplay. It was my third book by de Bernières, and it was interesting to read in the afterword that he sees this one as being suited to 12-year-olds, yet most likely to be read by adults. Each of these 11 stories has a fantastic first line – my favorite, from “Sacred Heart,” being “In ninth grade I was a great admirer of Jesus Christ” – but often I felt that these stories of relationships on the brink did not live up to their openers. Most take place in a major city (Chicago, New York, San Francisco) or a holiday destination (Bora Bora, China, Mexico, Spain), but no matter the setting, the terrain is generally a teen girl flirting with danger or a marriage about to implode because the secret of a recent or long-ago affair has come out into the open.

Each of these 11 stories has a fantastic first line – my favorite, from “Sacred Heart,” being “In ninth grade I was a great admirer of Jesus Christ” – but often I felt that these stories of relationships on the brink did not live up to their openers. Most take place in a major city (Chicago, New York, San Francisco) or a holiday destination (Bora Bora, China, Mexico, Spain), but no matter the setting, the terrain is generally a teen girl flirting with danger or a marriage about to implode because the secret of a recent or long-ago affair has come out into the open. (Visible darkness must have a colour, right?) I had long wanted to read this and finally came across a secondhand copy the other day. What I never realized was that, at 84 pages, it is essentially an extended essay: It started life as a lecture given at Johns Hopkins in 1989, was expanded into a Vanity Fair essay, and then further expanded into this short book.

(Visible darkness must have a colour, right?) I had long wanted to read this and finally came across a secondhand copy the other day. What I never realized was that, at 84 pages, it is essentially an extended essay: It started life as a lecture given at Johns Hopkins in 1989, was expanded into a Vanity Fair essay, and then further expanded into this short book. Rewilding is a big buzz word in current nature and environmental writing. Few could be said to have played as major a role in the UK’s successful species reintroduction projects as Roy Dennis, who has been involved with the RSPB and other key organizations since the late 1950s. He trained as a warden at two of the country’s most famous bird observatories, Lundy Island and Fair Isle. Most of his later work was to focus on birds: white-tailed eagles, red kites, and ospreys. Some of these projects extended into continental Europe. He also writes about the special challenges posed by mammal reintroductions; beavers get a chapter of their own. Every initiative is described in exhaustive detail, full of names and dates, whereas I would have been okay with an overview. This feels like more of an insider’s history rather than a layman’s introduction. I have popped it on my husband’s bedside table in hopes that, with his degree in wildlife conservation, he’ll be more interested in the nitty-gritty.

Rewilding is a big buzz word in current nature and environmental writing. Few could be said to have played as major a role in the UK’s successful species reintroduction projects as Roy Dennis, who has been involved with the RSPB and other key organizations since the late 1950s. He trained as a warden at two of the country’s most famous bird observatories, Lundy Island and Fair Isle. Most of his later work was to focus on birds: white-tailed eagles, red kites, and ospreys. Some of these projects extended into continental Europe. He also writes about the special challenges posed by mammal reintroductions; beavers get a chapter of their own. Every initiative is described in exhaustive detail, full of names and dates, whereas I would have been okay with an overview. This feels like more of an insider’s history rather than a layman’s introduction. I have popped it on my husband’s bedside table in hopes that, with his degree in wildlife conservation, he’ll be more interested in the nitty-gritty. The title is the word for winter in the Northern Sámi language. Galloway, a journalist, traded in New York City for Arctic Norway after a) a DNA test told her that she had Sámi blood and b) she met and fell for Áilu, a reindeer herder, at a wedding. She enrolled in an intensive language learning course at university level and got used to some major cultural changes: animals were co-workers here rather than pets (like the two cats she brought with her); communal meals and drawn-out goodbyes were not the done thing; and shamans were still active (one helped them find a key she lost). Footwear neatly sums up the difference. The Prada heels she brought “just in case” ended up serving as hammers; instead, she helped Áilu’s mother make reindeer skins into boots. Two factors undermined my enjoyment: Alternating chapters about her unhappy upbringing in Indiana don’t add much of interest, and, after her relationship with Áilu ends, the book feels aimless. However, I appreciated her words about DNA not defining you, and family being what you make it.

The title is the word for winter in the Northern Sámi language. Galloway, a journalist, traded in New York City for Arctic Norway after a) a DNA test told her that she had Sámi blood and b) she met and fell for Áilu, a reindeer herder, at a wedding. She enrolled in an intensive language learning course at university level and got used to some major cultural changes: animals were co-workers here rather than pets (like the two cats she brought with her); communal meals and drawn-out goodbyes were not the done thing; and shamans were still active (one helped them find a key she lost). Footwear neatly sums up the difference. The Prada heels she brought “just in case” ended up serving as hammers; instead, she helped Áilu’s mother make reindeer skins into boots. Two factors undermined my enjoyment: Alternating chapters about her unhappy upbringing in Indiana don’t add much of interest, and, after her relationship with Áilu ends, the book feels aimless. However, I appreciated her words about DNA not defining you, and family being what you make it. Native American poet Sharmagne Leland St.-John’s fifth collection is a nostalgic and bittersweet look at people and places from one’s past. There are multiple elegies for public figures – everyone from Janis Joplin to Virginia Woolf – as well as for some who aren’t household names but have important stories that should be commemorated, like Hector Pieterson, a 12-year-old boy killed during the Soweto Uprising for protesting enforced teaching of Afrikaans in South Africa in 1976. Many of the elegies are presented as songs. Personal sources of sadness, such as a stillbirth, disagreements with a daughter, and ageing, weigh as heavily as tragic world events.

Native American poet Sharmagne Leland St.-John’s fifth collection is a nostalgic and bittersweet look at people and places from one’s past. There are multiple elegies for public figures – everyone from Janis Joplin to Virginia Woolf – as well as for some who aren’t household names but have important stories that should be commemorated, like Hector Pieterson, a 12-year-old boy killed during the Soweto Uprising for protesting enforced teaching of Afrikaans in South Africa in 1976. Many of the elegies are presented as songs. Personal sources of sadness, such as a stillbirth, disagreements with a daughter, and ageing, weigh as heavily as tragic world events. Coming in at under 260 pages, this isn’t your standard comprehensive biography. Sampson instead describes it as a “portrait,” one that takes up the structure of EBB’s nine-book epic poem, Aurora Leigh, and is concerned with themes of identity and the framing of stories. Elizabeth, as she is cosily called throughout the book, wrote poems that lend themselves to autobiographical interpretation – “her body of work creates a kind of looking glass in which, dimly, we make out the person who wrote it,” Sampson asserts.

Coming in at under 260 pages, this isn’t your standard comprehensive biography. Sampson instead describes it as a “portrait,” one that takes up the structure of EBB’s nine-book epic poem, Aurora Leigh, and is concerned with themes of identity and the framing of stories. Elizabeth, as she is cosily called throughout the book, wrote poems that lend themselves to autobiographical interpretation – “her body of work creates a kind of looking glass in which, dimly, we make out the person who wrote it,” Sampson asserts.

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Merritt asked about the novel’s magic realist element and how stylistically different his novels have been from each other. He was glad she found the book funny, as “life is tragicomic.” In an effort not to get stuck in a rut, he deliberately ‘breaks the mould’ after each book and starts over. This has not made him popular with his publisher!

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Last year’s Dylan Thomas Prize winner interviewed this year’s winner, and it was clear that the mutual admiration was strong. Though I had mixed feelings about Luster (

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Shipstead (also a Dylan Thomas Prize winner) echoed something Leilani had said: that she starts a novel with questions, not answers. Such humility is refreshing, and a sure way to avoid being preachy in fiction. Her new novel, Great Circle, is among my

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Lockwood is the only novelist to be included on the Atlantic’s roster of best tweets. She and Nina Stibbe, who interviewed her, agreed that 1) things aren’t funny when they try too hard and 2) the Internet used to be a taboo subject for fiction – producing time-stamped references that editors used to remove. “I had so many observations and I didn’t know where to put them,” Lockwood said, and it seems to her perverse to not write about something that is such a major part of our daily lives. The title of her Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel, No One Is Talking About This (

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Like Lockwood, Pachico was part of the “10 @ 10” series featuring debut novelists (though her first book, the linked story collection

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

Speaking to Arifa Akbar about

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

I’ve read more of and gotten on better with Heti’s work than Cusk’s, so this was a rare case of being perhaps more interested in interviewer than interviewee. Heti said that, compared with the Outline trilogy, Cusk’s new novel Second Place feels wilder and more instinctual. Cusk, speaking from the Greek island of Tinos, where she is researching marble quarrying, described her book in often vague yet overall intriguing terms: it’s about exile and the illicit, she said; about femininity and entitlement to speak; about the domestic space and how things are legitimized; about the adoption of male values and the “rightness of the artist.”

Ante remembers the years when her mother was absent but promised to send for the rest of the family soon: “You said all I needed to do was to sleep and before I knew it, / you’d be back. But I woke to the rice that needed rinsing, / my siblings’ school uniforms that needed ironing.” The medical profession as a family legacy and noble calling is a strong element of these poems, especially in “Invisible Women,” an ode to the “goddesses of caring and tending” who walk the halls of any hospital. Hard work is a matter of survival, and family – whether physically present or not – bolsters weary souls. A series of short, untitled poems are presented as tape recordings made for her mother.

Ante remembers the years when her mother was absent but promised to send for the rest of the family soon: “You said all I needed to do was to sleep and before I knew it, / you’d be back. But I woke to the rice that needed rinsing, / my siblings’ school uniforms that needed ironing.” The medical profession as a family legacy and noble calling is a strong element of these poems, especially in “Invisible Women,” an ode to the “goddesses of caring and tending” who walk the halls of any hospital. Hard work is a matter of survival, and family – whether physically present or not – bolsters weary souls. A series of short, untitled poems are presented as tape recordings made for her mother. In “Happily Ever After,” Lyssa works in the gift shop of a Titanic replica and is cast as an extra in a pop star’s music video. Mythical sea monsters are contrasted with the real dangers of her life, like cancer and racism. “Anything Could Disappear” was a favourite of mine, though it begins with that unlikely scenario of a single woman acquiring a baby as if by magic. What starts off as a burden becomes a bond she can’t bear to let go. A family is determined to clear the name of their falsely imprisoned ancestor in “Alcatraz.” In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” (a mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow), photojournalist Rena is wary about attending the wedding of a friend she met when their plane was detained in Africa some years ago. The only wedding she’s been in is her sister’s, which ended badly.

In “Happily Ever After,” Lyssa works in the gift shop of a Titanic replica and is cast as an extra in a pop star’s music video. Mythical sea monsters are contrasted with the real dangers of her life, like cancer and racism. “Anything Could Disappear” was a favourite of mine, though it begins with that unlikely scenario of a single woman acquiring a baby as if by magic. What starts off as a burden becomes a bond she can’t bear to let go. A family is determined to clear the name of their falsely imprisoned ancestor in “Alcatraz.” In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” (a mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow), photojournalist Rena is wary about attending the wedding of a friend she met when their plane was detained in Africa some years ago. The only wedding she’s been in is her sister’s, which ended badly. The obsession began when he was eight years old and someone brought him a dead swift fledgling for his taxidermy hobby. Ever since, he’s dated the summer by their arrival. “It is always summer for them,” though, as his opening line has it. This monograph is structured chronologically. Much like Tim Dee does in

The obsession began when he was eight years old and someone brought him a dead swift fledgling for his taxidermy hobby. Ever since, he’s dated the summer by their arrival. “It is always summer for them,” though, as his opening line has it. This monograph is structured chronologically. Much like Tim Dee does in  As I’ve found with a number of Little Toller releases now (On Silbury Hill,

As I’ve found with a number of Little Toller releases now (On Silbury Hill,  Whitney’s father, Ron Davis, is a Stanford geneticist whose research has contributed to the Human Genome Project. He has devoted himself to studying ME/CFS, which affects 20 million people worldwide yet receives little research funding; he calls it “the last major disease we know nothing about.” Testing his son’s blood, he found a problem with the citric acid cycle that produces ATP, essential fuel for the body’s cells – proof that there was a physiological reason for Whitney’s condition. Frustratingly, though, a Stanford colleague who examined Whitney prescribed a psychological intervention. This is in line with the current standard of care for ME/CFS: a graded exercise regime (nigh on impossible for someone who can’t get out of bed) and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Whitney’s father, Ron Davis, is a Stanford geneticist whose research has contributed to the Human Genome Project. He has devoted himself to studying ME/CFS, which affects 20 million people worldwide yet receives little research funding; he calls it “the last major disease we know nothing about.” Testing his son’s blood, he found a problem with the citric acid cycle that produces ATP, essential fuel for the body’s cells – proof that there was a physiological reason for Whitney’s condition. Frustratingly, though, a Stanford colleague who examined Whitney prescribed a psychological intervention. This is in line with the current standard of care for ME/CFS: a graded exercise regime (nigh on impossible for someone who can’t get out of bed) and cognitive behavioural therapy.

One that’s not pictured but that I definitely plan to read and review over the summer is God Is Not a White Man by Chine McDonald, which came out earlier this month.

One that’s not pictured but that I definitely plan to read and review over the summer is God Is Not a White Man by Chine McDonald, which came out earlier this month.

In mid-June I’m on the blog tour for Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau, a novel that’s perfect for the season’s reading – nostalgic for a teen girl’s music-drenched 1970s summer, and reminiscent of Curtis Sittenfeld’s work.

In mid-June I’m on the blog tour for Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau, a novel that’s perfect for the season’s reading – nostalgic for a teen girl’s music-drenched 1970s summer, and reminiscent of Curtis Sittenfeld’s work.

Silly Stuff (Recent Follows, Likes, Searches, and Comments)

Another review catch-up post and the first few of my 20 Books of Summer are coming up later this week. Before that … I’ve been saving up some funny follows and spam comments, as well as a couple of likes on Goodreads that were too apt not to share. I also always enjoy looking at the random searches that have led people to my blog. (Previously surveyed in May 2016, October 2016, June 2017, and July 2020.)

My blog has divine approval.

(I especially love the idea that I can find out “what he’s up to” by reading his blog.)

The right readers found my reviews.

Random searches:

July 29, 2020: shaun bythell anna, val howlett, ruth pavey, romance novel with a butler named bolt

September 15: meaning of ian love doreen, what is the meaning of the title clock dance?

November 20: ordinary planet comic, isabelle’s appearance in olive again

February 10, 2021: promise and fail soap by celestial church, review of the moon and sixpence, books less than 50 pages, winter soldier novel zimmer smoking pipe

March 24: one foot in the grave mr prosnett, employer and “silvie braun”, short poem about a black cat called scarlett

May 7: shaun bythell wedding, jessica fox shaun, who is shaun bythell wife, shaun bythell partner anna

(So much enduring interest in Shaun Bythell’s love life!!)

Spam comments that made me laugh:

August 22, 2020: “Ranunculus, Wax Flowers, Combined Greenery.” (from “Get well soon cards with flowers”)

November 27: “Hi there mates, fastidious paragraph and nice urging commented here, I am truly enjoying by these.”

December 2: “hi, i am woo from Sweden and i want to explain any thing about “pandemic”. Please ask me 🙂”

March 2, 2021: “carrie underwood songs sad”

If you blog, too, do you keep an eye on these things?

What’s the funniest one you had lately?