20 Books of Summer, #15–16: Andrew Beahrs and Elizabeth Graver

Today I have a biography-cum-cultural history of America’s wild foods and a novel about beekeeping and mental illness.

Twain’s Feast: Searching for America’s Lost Foods in the Footsteps of Samuel Clemens by Andrew Beahrs (2010)

(20 Books of Summer, #15) In 1879, Mark Twain, partway through the Grand Tour immortalized in A Tramp Abroad, was sick of bland, poor-quality European food and hankering for down-home American cooking. He drew up a list of 80 foodstuffs he couldn’t wait to get back to: everything from soft-shell crabs to proper ice water. “The menu shouts of a joyous abundance,” Beahrs writes. “It testifies to a deep bond in Twain’s mind between eating and tasting and celebrating … rooted food that would live forever in his memory.”

(20 Books of Summer, #15) In 1879, Mark Twain, partway through the Grand Tour immortalized in A Tramp Abroad, was sick of bland, poor-quality European food and hankering for down-home American cooking. He drew up a list of 80 foodstuffs he couldn’t wait to get back to: everything from soft-shell crabs to proper ice water. “The menu shouts of a joyous abundance,” Beahrs writes. “It testifies to a deep bond in Twain’s mind between eating and tasting and celebrating … rooted food that would live forever in his memory.”

Beahrs goes in search of some of those trademark dishes and explores their changes in production over the last 150 years. In some cases, the creatures and their habitats are so endangered that we don’t eat them anymore, like Illinois’ prairie chickens and Maryland’s terrapins, but he has experts show him where remnant populations live. In San Francisco Bay, he helps construct an artificial oyster reef. He meets cranberry farmers in Massachusetts and maple tree tappers in Vermont. At the Louisiana Foodservice EXPO he gorges on “fried oysters and fried shrimp and fries. I haven’t had much green, but I’ve had pecan waffles with bacon, and I’ve inserted beignets and café au lait between meals with the regularity of an Old Testament prophet chanting ‘begat.’”

But my favorite chapter was about attending a Coon Supper in Arkansas, a local tradition that has been in existence since the 1930s. Raccoons are hunted, butchered, steamed in enormous kettles, and smoked before the annual fundraising meal attended by 1000 people. Raccoon meat is greasy and its flavor sounds like an acquired taste: “a smell like nothing I’ve smelled before but which I’ll now recognize until I die (not, I hope, as a result of eating raccoon).” Beahrs has an entertaining style and inserts interesting snippets from Twain’s life story, as well as recipes from 19th-century cookbooks. There are lots of books out there about the country’s increasingly rare wild foods, but the Twain connection is novel, if niche.

Source: A remainder book from Wonder Book (Frederick, Maryland)

My rating:

The Honey Thief by Elizabeth Graver (1999)

(20 Books of Summer, #16) Ever since I read The End of the Point (which featured in one of my Six Degrees posts), I’ve meant to try more by Graver. This was her second novel, a mother-and-daughter story that unearths the effects of mental illness on a family. Eleven-year-old Eva has developed a bad habit of shoplifting, so her mother Miriam moves them out from New York City to an upstate farmhouse for the summer. But in no time Eva, slipping away from her elderly babysitter’s supervision and riding her bike into the countryside, is stealing jars of honey from a roadside stand. She keeps going back and strikes up a friendship with the middle-aged beekeeper, Burl, whom she seems to see as a replacement for her father, Francis, who died of a heart attack when she was six.

(20 Books of Summer, #16) Ever since I read The End of the Point (which featured in one of my Six Degrees posts), I’ve meant to try more by Graver. This was her second novel, a mother-and-daughter story that unearths the effects of mental illness on a family. Eleven-year-old Eva has developed a bad habit of shoplifting, so her mother Miriam moves them out from New York City to an upstate farmhouse for the summer. But in no time Eva, slipping away from her elderly babysitter’s supervision and riding her bike into the countryside, is stealing jars of honey from a roadside stand. She keeps going back and strikes up a friendship with the middle-aged beekeeper, Burl, whom she seems to see as a replacement for her father, Francis, who died of a heart attack when she was six.

Alternating chapters look back at how Miriam met Francis and how she gradually became aware of his bipolar disorder. This strand seems to be used to prop up Miriam’s worries about Eva (since bipolar has a genetic element); while it feels true to the experience of mental illness, it’s fairly depressing. Meanwhile, Burl doesn’t become much of a presence in his own right, so he and the beekeeping feel incidental, maybe only included because Graver kept/keeps bees herself. Although Eva is an appealingly plucky character, I’d recommend any number of bee-themed novels, such as The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd, The History of Bees by Maja Lunde, and even Generation A by Douglas Coupland, over this one.

Source: Secondhand copy from Beltie Books, Wigtown

My rating:

The Bitch by Pilar Quintana: Blog Tour and #WITMonth 2020, Part I

My first selection for Women in Translation Month is an intense Colombian novella originally published in 2017 and translated from the Spanish by Lisa Dillman. The Bitch, which won the Colombian Biblioteca de Narrativa Prize and has been preserved in a time capsule in Bogotá, is Pilar Quintana’s first book to become available in English translation.

The title is literal, yet its harshness is deliberate: It’s clear from the first scene onwards that this is no cosy tale for animal lovers. Doña Elodia, who runs a beachfront restaurant, has just found her dog dead on the sand, killed either accidentally or intentionally by rat poison. Just six days before, the dog had given birth to 10 puppies. Damaris agrees to adopt a grey female from the litter. Her husband Rogelio already keeps three guard dogs at their shantytown shack and is mean to them, but Damaris is determined things will be different with this pup.

Damaris seems to be cursed, though: she’s still haunted by the death by drowning of a neighbour boy, Nicolasito Reyes, who didn’t heed her warning about the dangerous rocks and waves; she lost her mother to a stray bullet when she was 14; and despite trying many herbs and potions she and Rogelio have not been able to have children. Tenderness has ebbed and flowed in her marriage; “She was over forty now, the age women dry up.” Her cousin disapproves of the attention she lavishes on the puppy, Chirli – the name she would have given a daughter.

Chirli doesn’t repay Damaris’ love with the devotion she expects. She’d been hoping for a faithful companion during her work as a caretaker and cleaner at the big houses on the bluff, but Chirli keeps running off – once disappearing for 33 days – and coming back pregnant. The dog serves as a symbol of parts of herself she doesn’t want to acknowledge, and desires she has repressed. This dark story of guilt and betrayal set at the edge of a menacing jungle can be interpreted at face value or as an allegory – the latter was the only way I could accept.

I appreciated the endnotes about the book design. The terrific cover photograph by Felipe Manorov Gomes was taken on a Brazilian beach. The stray’s world-weary expression is perfect.

The Bitch is published by World Editions on the 20th of August. I was delighted to be asked to participate in the blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Are you doing any special reading for Women in Translation month this year?

Summery Classics by J. L. Carr and L. P. Hartley

“Do you remember what that summer was like? – how much more beautiful than any since?”

These two slightly under-the-radar classics made for perfect heatwave reading over the past couple of weeks: very English and very much of the historical periods that they evoke, they are nostalgic works remembering one summer when everything changed – or could have.

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr (1980)

Summer 1920, North Yorkshire. Tom Birkin, a First World War veteran whose wife has left him, arrives in Oxgodby to uncover the local church’s wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long since whitewashed over. With nothing waiting for him back in London and no plans beyond this commission, he gives himself over to the daily rhythms of working, eating and sleeping – “There was so much time that marvelous summer.” This simple life is punctuated by occasional incidents like a Sunday school hayride and picnic, and filling in as a lay preacher at a nearby chapel. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, who is searching for the grave of their patroness’ ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget.

Summer 1920, North Yorkshire. Tom Birkin, a First World War veteran whose wife has left him, arrives in Oxgodby to uncover the local church’s wall painting of the Judgment Day, assumed to be the work of a medieval monk and long since whitewashed over. With nothing waiting for him back in London and no plans beyond this commission, he gives himself over to the daily rhythms of working, eating and sleeping – “There was so much time that marvelous summer.” This simple life is punctuated by occasional incidents like a Sunday school hayride and picnic, and filling in as a lay preacher at a nearby chapel. Also embarked on a quest into the past is Charles Moon, who is searching for the grave of their patroness’ ancestor in the churchyard. Moon, too, has a war history he’d rather forget.

Though it barely exceeds 100 pages, this novella is full of surprises – about Moon, about the presumed identity and fate of the centuries-dead figures he and Birkin come to be obsessed with, and about the emotional connection that builds between Birkin and Reverend Keach’s wife, Alice. “It is now or never; we must snatch at happiness as it flies,” Birkin declares, but did he take his own advice? There is something achingly gorgeous about this not-quite-love story, as evanescent as ideal summer days. Carr writes in a foreword that he intended to write “a rural idyll along the lines of Thomas Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree.” He indeed created something Hardyesque with this tragicomic rustic romance; I was also reminded of another very English classic I reviewed earlier in the year: Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee.

Source: Free bookshop

My rating:

A contemporary readalike: The Offing by Benjamin Myers

The Go-Between by L. P. Hartley (1953)

Summer 1900, Norfolk. Twelve-year-old Leo Colston is invited to spend the several July weeks leading up to his birthday at his school friend Marcus Maudsley’s home, Brandham Hall. Although the fatherless boy is keenly aware of the class difference between their families, in a year of learning to evade bullies he’s developed some confidence in his skills and pluck, fancying himself an amateur magician and gifted singer. Being useful makes him feel less like a charity case, so he eagerly agrees to act as “postman” for Marcus’s older sister, Marian, who exchanges frequent letters with their tenant farmer, Ted Burgess. Marian, engaged to Hugh, a viscount and injured Boer War veteran, insists the correspondence is purely business-related, but Leo suspects he’s abetting trysts the family would disapprove of.

Leo is right on the cusp of adolescence, a moment of transition that mirrors the crossing into a new century. As he glories in the summer’s mounting heat, “a liberating power with its own laws,” and mentally goads the weather into hitting ever greater extremes, he pushes against the limits of his innocence, begging Ted to tell him about “spooning” (that is, the facts of life). The heat becomes a character in its own right, gloweringly presiding over the emotional tension caused by secrets, spells and betrayals. And yet this is also a very funny novel: I loved Leo’s Franglais conversations with Marcus, and the confusion over mispronouncing “Hugh” as “you.” In places the tone even reminded me of Cold Comfort Farm.

Leo is right on the cusp of adolescence, a moment of transition that mirrors the crossing into a new century. As he glories in the summer’s mounting heat, “a liberating power with its own laws,” and mentally goads the weather into hitting ever greater extremes, he pushes against the limits of his innocence, begging Ted to tell him about “spooning” (that is, the facts of life). The heat becomes a character in its own right, gloweringly presiding over the emotional tension caused by secrets, spells and betrayals. And yet this is also a very funny novel: I loved Leo’s Franglais conversations with Marcus, and the confusion over mispronouncing “Hugh” as “you.” In places the tone even reminded me of Cold Comfort Farm.

Like A Month in the Country, this autobiographical story is an old man’s reminiscences, going back half a century in memory – but here Leo gets the chance to go back in person as well, seeing what has become of Brandham Hall and meeting one of the major players from that summer drama that branded him for life. I thought this masterfully done in every way: the class divide, the picture of childhood tipping over into the teenage years, the oppressive atmosphere, the comical touches. You know from the famous first line onwards (“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”) that this will juxtapose past and present – which, of course, has now become past and further past – in a powerful way, similar to Moon Tiger, my favorite fiction read of last year. I’ll be exploring more of Hartley’s work.

(Note: Although I am a firm advocate of DNFing if a book is not working for you, I would also like to put in a good word for trying a book again another time. Ironically, this had been a DNF for me last summer: I found the prologue, with all its talk of the zodiac, utterly dull. I had the same problem with Cold Comfort Farm, literally trying about three times to get through the prologue and failing. So, for both, I eventually let myself skip the prologue, read the whole novel, and then go back to the prologue. Worked a treat.)

Source: Ex-library copy bought from Lambeth Library when I worked in London

My rating:

A contemporary readalike: Atonement by Ian McEwan

20 Books of Summer, #13–14: Ruth Reichl and Alice Steinbach

Just three weeks remain in this challenge. I’m reading another four books towards it, and have two more to pick up during our mini-break to Devon and Dorset this coming weekend. A few of my choices are long and/or slow-moving reads, though, so I have a feeling I’ll be reading right down to the wire…

Today I have another two memoirs linked by France and its cuisine.

Tender at the Bone: Growing Up at the Table by Ruth Reichl (1998)

(20 Books of Summer, #13) I’ve read Reichl’s memoirs out of order, starting with Garlic and Sapphires (2005), about her time as a New York Times food critic, and moving on to Comfort Me with Apples (2001), about her involvement in California foodie culture in the 1970s–80s. Whether because I’d been primed by the disclaimer in the author’s note (“I have occasionally embroidered. I learned early that the most important thing in life is a good story”) or not, I sensed that certain characters and scenes were exaggerated here. Although I didn’t enjoy her memoir of her first 30 years as much as either of the other two I’d read, it was still worth reading.

(20 Books of Summer, #13) I’ve read Reichl’s memoirs out of order, starting with Garlic and Sapphires (2005), about her time as a New York Times food critic, and moving on to Comfort Me with Apples (2001), about her involvement in California foodie culture in the 1970s–80s. Whether because I’d been primed by the disclaimer in the author’s note (“I have occasionally embroidered. I learned early that the most important thing in life is a good story”) or not, I sensed that certain characters and scenes were exaggerated here. Although I didn’t enjoy her memoir of her first 30 years as much as either of the other two I’d read, it was still worth reading.

The cover image is a genuine photograph taken by Reichl’s German immigrant father, book designer Ernst Reichl, in 1955. Early on, Reichl had to fend for herself in the kitchen: her bipolar mother hoarded discount food even it was moldy, so the family quickly learned to avoid her dishes made with ingredients that were well past their best. Like Eric Asimov and Anthony Bourdain, whose memoirs I’ve also reviewed this summer, Reichl got turned on to food by a top-notch meal in France. Food was a form of self-expression as well as an emotional crutch in many situations to come: during boarding school in Montreal, her rebellious high school years, and while living off of trendy grains and Dumpster finds at a co-op in Berkeley.

Reichl worked with food in many ways during her twenties. She was a waitress during college in Michigan, and a restaurant collective co-owner in California; she gave cooking lessons; she catered parties; and she finally embarked on a career as a restaurant critic. Her travels took her to France (summer camp counselor; later, wine aficionado), Morocco (with her college roommate), and Crete (a honeymoon visit to her favorite professor). Raised in New York City, she makes her way back there frequently, too. Overall, the book felt a bit scattered to me, with few if any recipes that I would choose to make, and the relationship with a mentally ill mother was so fraught that I will probably avoid Reichl’s two later books focusing on her mother.

Source: Awesomebooks.com

My rating:

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman by Alice Steinbach (2004)

(20 Books of Summer, #14) Steinbach makes a repeat appearance in my summer reading docket: her 2000 travel book Without Reservations was one of my 2018 selections. In that book, she took a sabbatical during her 50s to explore Paris, England, and Italy. Here she continues her efforts at lifelong learning by taking up some sort of lessons everywhere she goes. The long first section sees her back in Paris, enrolling at the Hotel Ritz’s Escoffier École de Gastronomie Française. She’s self-conscious about having joined late, being older than the other students and having to rely on the translator rather than the chef’s instructions, but she’s determined to keep up as the class makes omelettes, roast quail and desserts.

(20 Books of Summer, #14) Steinbach makes a repeat appearance in my summer reading docket: her 2000 travel book Without Reservations was one of my 2018 selections. In that book, she took a sabbatical during her 50s to explore Paris, England, and Italy. Here she continues her efforts at lifelong learning by taking up some sort of lessons everywhere she goes. The long first section sees her back in Paris, enrolling at the Hotel Ritz’s Escoffier École de Gastronomie Française. She’s self-conscious about having joined late, being older than the other students and having to rely on the translator rather than the chef’s instructions, but she’s determined to keep up as the class makes omelettes, roast quail and desserts.

Full disclosure: I’ve only read the first chapter for now as it’s the only one directly relevant to food – in others she takes dance lessons in Japan, studies art in Cuba, trains Border collies in Scotland, etc. – but I was enjoying it and will go back to it before the end of the year.

Source: Free bookshop

Recommended July Releases: Donoghue, Maizes, Miller, Parikian, Trethewey

My five new releases for July include historical pandemic fiction, a fun contemporary story about a father-and-daughter burglar team, a new poetry collection from Carcanet Press, a lighthearted nature/travel book, and a poetic bereavement memoir about a violent death.

The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

Donoghue’s last two novels, The Wonder and Akin, were big hits with me. Less than a year after the contemporary-set Akin, she’s back to a historical setting – and an uncannily pertinent pandemic theme – with her latest. In 1918, Julia Power is a nurse on a Dublin maternity ward. It’s Halloween and she is about to turn 30, making her a spinster for her day; she lives with her mute, shell-shocked veteran brother, Tim, and his pet magpie.

Donoghue’s last two novels, The Wonder and Akin, were big hits with me. Less than a year after the contemporary-set Akin, she’s back to a historical setting – and an uncannily pertinent pandemic theme – with her latest. In 1918, Julia Power is a nurse on a Dublin maternity ward. It’s Halloween and she is about to turn 30, making her a spinster for her day; she lives with her mute, shell-shocked veteran brother, Tim, and his pet magpie.

Because she’s already had “the grip” (influenza), she is considered immune and is one of a few staff members dealing with the flu-ridden expectant mothers in quarantine in her overcrowded hospital. Each patient serves as a type, and Donoghue whirls through all the possible complications of historical childbirth: stillbirth, obstructed labor, catheterization, forceps, blood loss, transfusion, maternal death, and so on.

It’s not for the squeamish, and despite my usual love of medical reads, I felt it was something of a box-ticking exercise, with too much telling about medical procedures and recent Irish history. Because of the limited time frame – just three days – the book is far too rushed. We simply don’t have enough time to get to know Julia through and through, despite her first-person narration; the final 20 pages, in particular, are so far-fetched and melodramatic it’s hard to believe in a romance you’d miss if you blinked. And the omission of speech marks just doesn’t work – it’s downright confusing with so many dialogue-driven scenes.

Donoghue must have been writing this well before Covid-19, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the publication was hurried forward to take advantage of the story’s newfound relevance. It shows: what I read in May and June felt like an unpolished draft, with threads prematurely tied up to meet a deadline. This was an extremely promising project that, for me, was let down by the execution, but it’s still a gripping read that I wouldn’t steer you away from if you find the synopsis appealing. (Some more spoiler-y thoughts here.)

Prescient words about pandemics:

“All over the globe … some flu patients are dropping like flies while others recover, and we can’t solve the puzzle, nor do a blasted thing about it. … There’s no rhyme or reason to who’s struck down.”

“Doctor Lynn went on, As for the authorities, I believe the epidemic will have run its course before they’ve agreed to any but the most feeble action. Recommending onions and eucalyptus oil! Like sending beetles to stop a steamroller.”

Why the title?

Flu comes from the phrase “influenza delle stelle” – medieval Italians thought that illness was fated by the stars. There’s also one baby born a “stargazer” (facing up) and some literal looking up at the stars in the book.

My rating:

My thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

Other People’s Pets by R.L. Maizes

This is Maizes’ debut novel, after her 2019 short story collection We Love Anderson Cooper. Louise “La La” Fine and her father, Zev, share an unusual profession: While outwardly they are a veterinary student and a locksmith, respectively, for many years they broke into homes and sold the stolen goods. Despite close shaves, they’ve always gotten away with it – until now. When Zev is arrested, La La decides to return to her criminal ways just long enough to raise the money to post bail for him. But she doesn’t reckon on a few complications, like her father getting fed up with house arrest, her fiancé finding out about her side hustle, and her animal empathy becoming so strong that when she goes into a house she not only pilfers valuables but also cares for the needs of ailing pets inside.

This is Maizes’ debut novel, after her 2019 short story collection We Love Anderson Cooper. Louise “La La” Fine and her father, Zev, share an unusual profession: While outwardly they are a veterinary student and a locksmith, respectively, for many years they broke into homes and sold the stolen goods. Despite close shaves, they’ve always gotten away with it – until now. When Zev is arrested, La La decides to return to her criminal ways just long enough to raise the money to post bail for him. But she doesn’t reckon on a few complications, like her father getting fed up with house arrest, her fiancé finding out about her side hustle, and her animal empathy becoming so strong that when she goes into a house she not only pilfers valuables but also cares for the needs of ailing pets inside.

Flashbacks to La La’s growing-up years, especially her hurt over her mother leaving, take this deeper than your average humorous crime caper. The way the plot branches means that for quite a while Zev and La La are separated, and I grew a bit weary of extended time in Zev’s company, but this was a great summer read – especially for animal lovers – that never lost my attention. The magic realism of the human‒pet connection is believable and mild enough not to turn off readers who avoid fantasy. Think The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley meets Hollow Kingdom.

My rating:

My thanks to the author and Celadon Books for the free e-copy for review.

The Long Beds by Kate Miller

Here and there; now and then: the poems in Miller’s second collection enlarge such dichotomies by showcasing the interplay of the familiar and the foreign. A scientist struggles to transcribe birdsong, and a poppy opens in slow motion. “Flag” evokes the electric blue air and water of a Greek island, while “The Quarters” is set in the middle of the night in a French village. A few commissions, including “Waterloo Sunrise,” stick close to home in London or other southern England locales.

Here and there; now and then: the poems in Miller’s second collection enlarge such dichotomies by showcasing the interplay of the familiar and the foreign. A scientist struggles to transcribe birdsong, and a poppy opens in slow motion. “Flag” evokes the electric blue air and water of a Greek island, while “The Quarters” is set in the middle of the night in a French village. A few commissions, including “Waterloo Sunrise,” stick close to home in London or other southern England locales.

Various poems, including the multi-part “Album Without Photographs,” are about ancestor Muriel Miller’s experiences in India and Britain in the 1910s-20s. “Keepers of the States of Sleep and Wakefulness, fragment from A Masque,” patterned after “The Second Masque” by Ben Jonson, is an up-to-the-minute one written in April that names eight nurses from the night staff at King’s College Hospital (and the short YouTube film based on it is dedicated to all NHS nurses).

My two favorites were “Outside the Mind Shop,” in which urban foxes tear into bags of donations outside a charity shop one night while the speaker lies awake, and “Knapsack of Parting Gifts” a lovely elegy to a lost loved one. I spotted a lot of alliteration and assonance in the former, especially. Thematically, the collection is a bit scattered, but there are a lot of individual high points.

My rating:

My thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

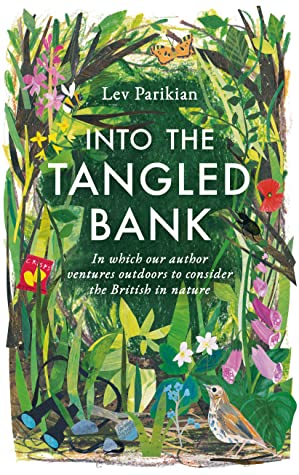

Into the Tangled Bank: In Which Our Author Ventures Outdoors to Consider the British in Nature by Lev Parikian

In the same way that kids sometimes write their address by going from the specific to the cosmic (street, city, country, continent, hemisphere, planet, galaxy), this book, a delightfully Bryson-esque tour, moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature.

In the same way that kids sometimes write their address by going from the specific to the cosmic (street, city, country, continent, hemisphere, planet, galaxy), this book, a delightfully Bryson-esque tour, moves ever outwards, starting with the author’s own home and garden and proceeding to take in his South London patch and his journeys around the British Isles before closing with the wonders of the night sky. By slowing down to appreciate what is all around us, he proposes, we might enthuse others to engage with nature.

With the zeal of a recent convert, he guides readers through momentous sightings and everyday moments of connection. As they were his gateway, many of these memories involve birds: looking for the year’s first swifts, trying to sketch a heron and realizing he’s never looked at one properly before, avoiding angry terns on the Farne Islands, ringing a storm petrel on Skokholm, and seeing white-tailed eagles on the Isle of Skye. He brings unique places to life, and pays tribute to British naturalists who paved the way for today’s nature-lovers by visiting the homes of Charles Darwin, Gilbert White, Peter Scott, and more.

I was on the blog tour for Parikian’s previous book, Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear?, in 2018. While the books are alike in levity (pun intended!), being full of self-deprecation and witty asides along with the astute observations, I think I enjoyed this one that little bit more for its all-encompassing approach to the experience of nature. I fully expect to see it on next year’s Wainwright Prize longlist (speaking of the Wainwright Prize, in yesterday’s post I correctly predicted four on the UK nature shortlist and two on the global conservation list!).

Readalikes (that happen to be from the same publisher): Under the Stars by Matt Gaw and The Seafarers by Stephen Rutt

My rating:

My thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey

Trethewey grew up in 1960s Mississippi with a Black mother and a white Canadian father, at a time when interracial marriage remained illegal in parts of the South. After her parents’ divorce, she and her mother, Gwen, moved to Georgia to start a new life, but her stepfather Joel was physically and psychologically abusive. Gwen’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to that Atlanta apartment on Memorial Drive after 30 years had passed. The blend of the objective (official testimonies and transcripts) and the subjective (interpreting photographs, and rendering dream sequences in poetic language) makes this a striking memoir, as delicate as it is painful. I recommend it highly to readers of Elizabeth Alexander and Dani Shapiro. (Full review forthcoming at Shiny New Books.)

Trethewey grew up in 1960s Mississippi with a Black mother and a white Canadian father, at a time when interracial marriage remained illegal in parts of the South. After her parents’ divorce, she and her mother, Gwen, moved to Georgia to start a new life, but her stepfather Joel was physically and psychologically abusive. Gwen’s murder opens and closes the book. Trethewey only returned to that Atlanta apartment on Memorial Drive after 30 years had passed. The blend of the objective (official testimonies and transcripts) and the subjective (interpreting photographs, and rendering dream sequences in poetic language) makes this a striking memoir, as delicate as it is painful. I recommend it highly to readers of Elizabeth Alexander and Dani Shapiro. (Full review forthcoming at Shiny New Books.)

My rating:

My thanks to Bloomsbury for the proof copy for review.

I’m reading two more July releases, Mostly Dead Things by Kristen Arnett (Corsair, 2 July; for Shiny New Books review), about a family taxidermy business in Florida, and The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams (William Heinemann, 2 July), about an unusual dictionary being compiled in the Victorian period and digitized in the present day.

I’m reading two more July releases, Mostly Dead Things by Kristen Arnett (Corsair, 2 July; for Shiny New Books review), about a family taxidermy business in Florida, and The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams (William Heinemann, 2 July), about an unusual dictionary being compiled in the Victorian period and digitized in the present day.

What July releases can you recommend?

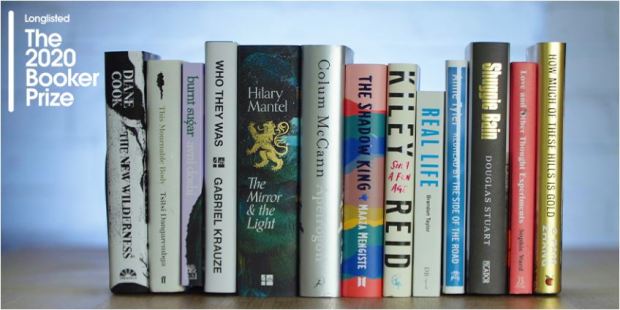

Quick Thoughts on the Booker Prize Longlist

The 13-strong 2020 Booker Prize longlist was announced this morning. Looking at friends’ Booker predictions/wish lists (Clare’s and Susan’s), I didn’t think I would be invested in this year’s prize race, yet the moment I saw the longlist I scurried to look up the titles I hadn’t heard of and to request others I realized I wanted to read after all.

In general, the list achieves a nice balance between established names and debut authors, and the gender, ethnicity and sexuality statistics are good.

(Descriptions of books not experienced are from the Goodreads blurbs.)

Read:

Only one so far and, alas, I thought it among the author’s poorest work to date:

- Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler (Chatto & Windus) – While this novella is perfectly readable – Tyler could write sympathetic characters like Micah and his Baltimore neighbors in her sleep – it felt incomplete and inconsequential, like an early draft that needed another subplot and plenty more scenes added in before it was ready for publication. Any potential controversy (illegitimate offspring and a few post-apocalyptic imaginings) is instantly neutralized, making the story feel toothless.

DNFed earlier in the year (but what do I know?):

The Mirror & The Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate) – I only managed to read 80 pages or so, then skimmed to page 200 before admitting defeat. I would be totally engrossed for up to 10 pages (exposition and Cromwell one-liners), but then everything got talky or plotty and I’d skim for 20‒30 pages and set it down. I lacked the necessary singlemindedness and felt overwhelmed by the level of detail and cast of characters, so never built up momentum. Still, I can objectively recognize the prose as top-notch. But is 900 pages not a wee bit indulgent? No editor would have dared cut it…

The Mirror & The Light by Hilary Mantel (4th Estate) – I only managed to read 80 pages or so, then skimmed to page 200 before admitting defeat. I would be totally engrossed for up to 10 pages (exposition and Cromwell one-liners), but then everything got talky or plotty and I’d skim for 20‒30 pages and set it down. I lacked the necessary singlemindedness and felt overwhelmed by the level of detail and cast of characters, so never built up momentum. Still, I can objectively recognize the prose as top-notch. But is 900 pages not a wee bit indulgent? No editor would have dared cut it…- Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (Bloomsbury) – “In the midst of a family crisis one late evening, white blogger Alix Chamberlain calls her African American babysitter, Emira, asking her to take toddler Briar to the local market for distraction. There, the security guard accuses Emira of kidnapping Briar, and Alix’s efforts to right the situation turn out to be good intentions selfishly mismanaged.”

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang (Virago) – “Both epic and intimate, blending Chinese symbolism and re-imagined history with fiercely original language and storytelling, How Much of These Hills Is Gold is a haunting adventure story … An electric debut novel set against the twilight of the American gold rush, two siblings are on the run in an unforgiving landscape—trying not just to survive but to find a home.”

On the shelf to read soon:

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (Picador) – “The unforgettable story of young Hugh ‘Shuggie’ Bain, a sweet and lonely boy who spends his 1980s childhood in run-down public housing in Glasgow, Scotland. Thatcher’s policies have put husbands and sons out of work, and the city’s notorious drugs epidemic is waiting in the wings.” (Out on August 6th. Proof copy from publisher)

Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (Picador) – “The unforgettable story of young Hugh ‘Shuggie’ Bain, a sweet and lonely boy who spends his 1980s childhood in run-down public housing in Glasgow, Scotland. Thatcher’s policies have put husbands and sons out of work, and the city’s notorious drugs epidemic is waiting in the wings.” (Out on August 6th. Proof copy from publisher)

Already wanted to read:

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (Bloomsbury) – Yes, I’m going to try this one again! (Requested from library)

Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid (Bloomsbury) – Yes, I’m going to try this one again! (Requested from library)- Real Life by Brandon Taylor (Daunt Books) – “An introverted young man from Alabama, black and queer, he has left behind his family without escaping the long shadows of his childhood. But over the course of a late-summer weekend, a series of confrontations with colleagues, and an unexpected encounter with an ostensibly straight, white classmate, conspire to fracture his defenses while exposing long-hidden currents of hostility and desire within their community.”

- Love and Other Thought Experiments by Sophie Ward (Corsair) – “Rachel and Eliza are hoping to have a baby. The couple spend many happy evenings together planning for the future. One night Rachel wakes up screaming and tells Eliza that an ant has crawled into her eye and is stuck there. She knows it sounds mad – but she also knows it’s true. As a scientist, Eliza won’t take Rachel’s fear seriously and they have a bitter fight. Suddenly their entire relationship is called into question.” (Requested from library)

Heard about for the first time and leapt to find:

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook (Oneworld) – “Bea, Agnes, and eighteen others volunteer to live in the Wilderness State as part of a study to see if humans can co-exist with nature … [This] explores a moving mother‒daughter relationship in a world ravaged by climate change and overpopulation.” (Out on August 13th. Requested from publisher)

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook (Oneworld) – “Bea, Agnes, and eighteen others volunteer to live in the Wilderness State as part of a study to see if humans can co-exist with nature … [This] explores a moving mother‒daughter relationship in a world ravaged by climate change and overpopulation.” (Out on August 13th. Requested from publisher)- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi (Hamish Hamilton) – “A searing debut novel about mothers and daughters, obsession and betrayal – for fans of Deborah Levy, Jenny Offill and Diana Evans … unpicks the slippery, choking cord of memory and myth that binds two women together, making and unmaking them endlessly.” (Out on July 30th. Requested from publisher)

Thought I didn’t want to read, but changed my mind:

Apeirogon by Colum McCann (Bloomsbury) – I’ve only read one book by McCann and have always meant to read more. But I judged this one by the title and assumed it was going to be yet another Greek myth update. (What an eejit!) “Bassam Aramin is Palestinian. Rami Elhanan is Israeli. They inhabit a world of conflict that colors every aspect of their daily lives, from the roads they are allowed to drive on, to the schools their daughters, Abir and Smadar, each attend, to the checkpoints, both physical and emotional, they must negotiate.” (Reading from library)

Apeirogon by Colum McCann (Bloomsbury) – I’ve only read one book by McCann and have always meant to read more. But I judged this one by the title and assumed it was going to be yet another Greek myth update. (What an eejit!) “Bassam Aramin is Palestinian. Rami Elhanan is Israeli. They inhabit a world of conflict that colors every aspect of their daily lives, from the roads they are allowed to drive on, to the schools their daughters, Abir and Smadar, each attend, to the checkpoints, both physical and emotional, they must negotiate.” (Reading from library)

Would read if it fell in my lap, but I’m not too bothered:

- Who They Was by Gabriel Krauze (4th Estate) – “An electrifying autobiographical British novel … This is a story of a London you won’t find in any guidebooks. This is a story about what it’s like to exist in the moment, about boys too eager to become men, growing up in the hidden war zones of big cities – and the girls trying to make it their own way.”

- The Shadow King by Maaza Mengiste (Canongate) – “A gripping novel set during Mussolini’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia, The Shadow King takes us back to the first real conflict of World War II, casting light on the women soldiers who were left out of the historical record.” I have seen unenthusiastic reviews from friends.

Don’t plan to read:

- This Mournable Body by Tsitsi Dangarembga (Faber & Faber) – “Anxious about her prospects after leaving a stagnant job, Tambudzai finds herself living in a run-down youth hostel in downtown Harare. … at every turn in her attempt to make a life for herself, she is faced with a fresh humiliation, until the painful contrast between the future she imagined and her daily reality ultimately drives her to a breaking point.” This is the third book in a trilogy and I have seen unfavorable reviews from friends.

Of course, Hilary will win; skip the shortlist announcement in September and go ahead and give her the Triple Crown! But I always discover at least a couple of gems through the Booker longlist each year, so I’m grateful to the judges (Margaret Busby (chair), editor, literary critic and former publisher; Lee Child, author; Sameer Rahim, author and critic; Lemn Sissay, writer and broadcaster; and Emily Wilson, classicist and translator) for highlighting some exciting books that I may not have been induced to try otherwise. I will probably end up reading only half of the longlist, but may readjust my plans after the shortlist comes out.

What do you think about the longlist? Have you read anything from it? Which nominees appeal to you?

Sarah Bennett, who went straight from university in Oxford to Paris for want of a better idea of what to do with her life, is called home to Warwickshire to be a bridesmaid in the wedding of her older sister, Louise, to Stephen Halifax, a wealthy novelist. Afterwards, Sarah decides to move to London and share a flat with a friend whose marriage has recently ended. As the months pass, she figures out life as a single girl in a big city and attends parties hosted by Louise – back from an extended European honeymoon – and others. Sarah eventually works out, from gossip and from confronting Louise herself, that her sister’s marriage isn’t as idyllic as it appeared. Both sisters find themselves at a loss as for what to do next.

Sarah Bennett, who went straight from university in Oxford to Paris for want of a better idea of what to do with her life, is called home to Warwickshire to be a bridesmaid in the wedding of her older sister, Louise, to Stephen Halifax, a wealthy novelist. Afterwards, Sarah decides to move to London and share a flat with a friend whose marriage has recently ended. As the months pass, she figures out life as a single girl in a big city and attends parties hosted by Louise – back from an extended European honeymoon – and others. Sarah eventually works out, from gossip and from confronting Louise herself, that her sister’s marriage isn’t as idyllic as it appeared. Both sisters find themselves at a loss as for what to do next. Another sisters novel, and the first book in my

Another sisters novel, and the first book in my

In 2009, Barkham set out to revive the childhood butterfly-watching hobby he’d shared with his father. The UK is home to 59 species, a manageable number to attempt to see in a season, although it does require a fair bit of travel and insider knowledge. I’ve read too much general history about the human relationship with butterflies (via Rainbow Dust by Peter Marren, which came out a few years later, and

In 2009, Barkham set out to revive the childhood butterfly-watching hobby he’d shared with his father. The UK is home to 59 species, a manageable number to attempt to see in a season, although it does require a fair bit of travel and insider knowledge. I’ve read too much general history about the human relationship with butterflies (via Rainbow Dust by Peter Marren, which came out a few years later, and

#3 A quote from McEwan on the cover convinced my book club to read the mediocre She’s Not There by Tamsin Grey. (I think the author was also a friend of a friend of someone in the group.) One morning, nine-year-old Jonah wakes up to find the front door of the house open and his mum gone. It takes just a week for the household to descend into chaos as Jonah becomes sole carer for his foul-mouthed little brother, six-year-old Raff. In this vivid London community, children are the stars and grown-ups, only sketchily drawn, continually fail them.

#3 A quote from McEwan on the cover convinced my book club to read the mediocre She’s Not There by Tamsin Grey. (I think the author was also a friend of a friend of someone in the group.) One morning, nine-year-old Jonah wakes up to find the front door of the house open and his mum gone. It takes just a week for the household to descend into chaos as Jonah becomes sole carer for his foul-mouthed little brother, six-year-old Raff. In this vivid London community, children are the stars and grown-ups, only sketchily drawn, continually fail them.

#6 The Mauritius location, plus a return to the “pigeon/pidgin” pun of the Kelman title, leads me to my final book, Genie and Paul by Natasha Soobramanien, about a brother and sister pair who left Mauritius for London as children and still speak Creole when joking. I reviewed this postcolonial response to Paul et Virginie (1788), the classic novel by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, for Wasafiri literary magazine in 2013. It was among my first professional book reviews, and I’ve enjoyed reviewing occasionally for Wasafiri since then – it gives me access to small-press books and BAME authors, which I otherwise don’t read often enough.

#6 The Mauritius location, plus a return to the “pigeon/pidgin” pun of the Kelman title, leads me to my final book, Genie and Paul by Natasha Soobramanien, about a brother and sister pair who left Mauritius for London as children and still speak Creole when joking. I reviewed this postcolonial response to Paul et Virginie (1788), the classic novel by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, for Wasafiri literary magazine in 2013. It was among my first professional book reviews, and I’ve enjoyed reviewing occasionally for Wasafiri since then – it gives me access to small-press books and BAME authors, which I otherwise don’t read often enough.

This was meant to be a buddy read with

This was meant to be a buddy read with

Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash: In her early 20s, Ash made multiple trips from London to stay in Newlyn: walking to the cove that bears her name, going out on fishing trawlers, and getting accepted into the small community. Gruelling and lonely, the fishermen’s way of life is fading away. The book goes deeper into Cornish history than non-locals need, but I enjoyed the literary allusions – the title is from Elizabeth Bishop. I liked the writing, but this was requested after me at the library, so I could only skim it.

Dark, Salt, Clear: Life in a Cornish Fishing Town by Lamorna Ash: In her early 20s, Ash made multiple trips from London to stay in Newlyn: walking to the cove that bears her name, going out on fishing trawlers, and getting accepted into the small community. Gruelling and lonely, the fishermen’s way of life is fading away. The book goes deeper into Cornish history than non-locals need, but I enjoyed the literary allusions – the title is from Elizabeth Bishop. I liked the writing, but this was requested after me at the library, so I could only skim it.

Bird Therapy by Joe Harkness: In 2013, Harkness was in such a bad place that he attempted suicide. Although he’s continued to struggle with OCD and depression in the years since then, birdwatching has given him a new lease on life. Avoiding the hobby’s more obsessive, competitive aspects (like listing and twitching), he focuses on the benefits of outdoor exercise and mindfulness. He can be lyrical when describing his Norfolk patch and some of his most magical sightings, but the writing is weak. (My husband helped crowdfund the book via Unbound.)

Bird Therapy by Joe Harkness: In 2013, Harkness was in such a bad place that he attempted suicide. Although he’s continued to struggle with OCD and depression in the years since then, birdwatching has given him a new lease on life. Avoiding the hobby’s more obsessive, competitive aspects (like listing and twitching), he focuses on the benefits of outdoor exercise and mindfulness. He can be lyrical when describing his Norfolk patch and some of his most magical sightings, but the writing is weak. (My husband helped crowdfund the book via Unbound.)

Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. Allotment gardening gives her opportunities to observe bee behaviour and marvel at their various lookalikes (like hoverflies), identify plants, work on herbal remedies, and photograph her finds. She delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning in a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. (On my runners-up of 2019 list)

Dancing with Bees: A Journey Back to Nature by Brigit Strawbridge Howard: Bees were the author’s gateway into a general appreciation of nature, something she lost for a time in midlife because of the rat race and family complications. Allotment gardening gives her opportunities to observe bee behaviour and marvel at their various lookalikes (like hoverflies), identify plants, work on herbal remedies, and photograph her finds. She delights in discovery and is devoted to lifelong learning in a book characterized by curiosity and warmth. (On my runners-up of 2019 list)

I think this year’s is an especially appealing longlist. It’s great to see small presses and debut authors getting recognition. I’ve now read 8 out of 13 (and skimmed one), and am interested in the rest, too, especially The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange. The final three, all combining nature and (auto)biographical writing, are On the Red Hill by Mike Parker, The Well-Gardened Mind by Sue Stuart-Smith, and Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent.

I think this year’s is an especially appealing longlist. It’s great to see small presses and debut authors getting recognition. I’ve now read 8 out of 13 (and skimmed one), and am interested in the rest, too, especially The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange. The final three, all combining nature and (auto)biographical writing, are On the Red Hill by Mike Parker, The Well-Gardened Mind by Sue Stuart-Smith, and Rootbound: Rewilding a Life by Alice Vincent.

Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back by Mark O’Connell: The same satirical outlook that made

Notes from an Apocalypse: A Personal Journey to the End of the World and Back by Mark O’Connell: The same satirical outlook that made