The Booker Prize 2023 Ceremony

Yesterday evening Eleanor Franzen of Elle Thinks and I had the enormous pleasure of attending the Booker Prize awards ceremony at Old Billingsgate in London. I won tickets through “The Booker Prize Book Club” Facebook group, which launched just 10 or so weeks ago but has already garnered over 6000 members from around the world. They ran a competition for shortlist book reviews and probably did not attract nearly as many entries as they expected to. This probably worked to my advantage, but as it’s the only prize I can recall winning for my writing, I am going to take it as a compliment nonetheless! I submitted versions of my reviews of If I Survive You and Western Lane – the only shortlistees that I’ve read – and it was the latter that won us tickets.

We arrived at the venue 15 minutes before the doors opened, sheltering from the drizzle under an overhang and keeping a keen eye on arrivals (Paul Lynch and sodden Giller Prize winner Sarah Bernstein, her partner wearing both a kilt and their several-week-old baby). Elle has a gift for small talk and we had a nice little chat with Jonathan Escoffery and his 4th Estate publicist before they were whisked inside. His head was spinning from the events of the week, including being part of a Booker delegation that met Queen Camilla.

There was a glitzy atmosphere, with a photographer-surrounded red carpet and large banners for each shortlisted novel along the opposite wall, plus an exhibit of the hand-bound editions created for each book. We enjoyed some glasses of champagne and canapés (the haddock tart was the winner) and collared Eric Karl Anderson of Lonesome Reader. It was lovely to catch up with him and Eleanor and do plenty of literary celebrity spotting: Graeme Macrae Burnet, Eleanor Catton, judge Mary Jean Chan, Natalie Haynes, Alan Hollinghurst, Anna James, Jean McNeil, Johanna Thomas-Corr (literary editor of the Sunday Times) and Sarah Waters. Later we were also able to chat with Julianne Pachico, our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel winner from 2017. She has recently gotten married and released her third novel.

We were allocated to Table 11 in the front right corner. Also at our table were some Booker Prize editorial staff members, the other competition winner (for a video review) and her guest, an Instagram influencer, a Reading Agency employee, and several more people. The three-course dinner was of a very high standard for mass catering and the wine flowed generously. I thoroughly enjoyed my meal. Afterward we had a bit of time for taking red carpet photos and one of Eleanor with the banner for our predicted winner, Prophet Song.

Some of you may have watched the YouTube livestream, or listened to the Radio 4 live broadcast. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s speech was a highlight. She spoke about the secret library at the Iranian prison where she was held for six years. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (there was a long waiting list among the prisoners and wardens, she said), and especially The Return by Hisham Matar meant a lot to her. From earlier on in the evening, I also enjoyed judge Adjoa Andoh’s dramatic reading of an excerpt from Possession in honour of the late Booker winner A.S. Byatt, and Shehan Karunatilaka’s tongue-in-cheek reflections on winning the Booker – he warned the next winner that they won’t write a word for a whole year.

There was a real variety of opinion in the room as to who would win. Earlier in the evening we’d spoken to people who favoured Western Lane, This Other Eden and The Bee Sting. But both Elle and I were convinced that Prophet Song would take home the trophy, and so it did. Despite his genuine display of shock, Paul Lynch was well prepared with an excellent speech in which he cited the apocrypha and Albert Camus. In a rapid-fire interview with host Samira Ahmed, he added that he can still remember sitting down and weeping after finishing The Mayor of Casterbridge, age 15 or 16, and hopes that his work might elicit similar emotion. I’m not sure that I plan on reading it myself, but from what I’ve heard it’s a powerfully convincing dystopian novel that brings political and social collapse home in a realistic way.

All in all, a great experience for which I am very grateful! (Thanks to Eleanor for all the photos.)

Have you read Prophet Song? Did you expect it to win the Booker Prize?

Six Degrees of Separation: From Our Wives Under the Sea to Groundskeeping

This month we began with Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield, one of my favourite novels of the year so far. It fuses horror-tinged magic realism with an emotionally resonant story of disconnection and grief. My review is here. I met the lovely Julia Armfield at the 2019 Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award ceremony at the London Library. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

This month we began with Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield, one of my favourite novels of the year so far. It fuses horror-tinged magic realism with an emotionally resonant story of disconnection and grief. My review is here. I met the lovely Julia Armfield at the 2019 Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award ceremony at the London Library. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

#1 This morning I was reading in Slime, Susanne Wedlich’s wide-ranging popular science book about primordial slime and mucus and biofilms and everything in between, about the peculiar creatures that thrive in the high-pressure deep sea level known as the hadal zone – which is of great significance in Armfield’s book. One of these is the hadal snailfish.

#1 This morning I was reading in Slime, Susanne Wedlich’s wide-ranging popular science book about primordial slime and mucus and biofilms and everything in between, about the peculiar creatures that thrive in the high-pressure deep sea level known as the hadal zone – which is of great significance in Armfield’s book. One of these is the hadal snailfish.

#2 I wish I could remember how I first heard about The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey (2010). Possibly the Bas Bleu catalogue? In any case, it was one of the books I requested on interlibrary loan during one of our stays with my parents in Maryland. Bailey, bedbound by chronic illness, saw in the snail that lived on her bedside table a microcosm of nature and animal behaviour. It’s a peaceful book about changing one’s pace and expectations, and thereby appreciating life.

#2 I wish I could remember how I first heard about The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey (2010). Possibly the Bas Bleu catalogue? In any case, it was one of the books I requested on interlibrary loan during one of our stays with my parents in Maryland. Bailey, bedbound by chronic illness, saw in the snail that lived on her bedside table a microcosm of nature and animal behaviour. It’s a peaceful book about changing one’s pace and expectations, and thereby appreciating life.

#3 The book is still much admired in nature writing circles. In fact, it was mentioned by Anita Roy, one of the panellists at last year’s New Networks for Nature conference – except she couldn’t remember the author’s name so asked the audience if anyone knew. Yours truly called it out (twice, so I could be heard over my face mask). Anyway, Josie George is in a similar position to Bailey and A Still Life records how she has cultivated close observation skills of the nature around her. I believe she was even inspired to keep a snail at one point.

#3 The book is still much admired in nature writing circles. In fact, it was mentioned by Anita Roy, one of the panellists at last year’s New Networks for Nature conference – except she couldn’t remember the author’s name so asked the audience if anyone knew. Yours truly called it out (twice, so I could be heard over my face mask). Anyway, Josie George is in a similar position to Bailey and A Still Life records how she has cultivated close observation skills of the nature around her. I believe she was even inspired to keep a snail at one point.

#4 Still Life is one of my favourite A.S. Byatt novels (this is not the first time I’ve used one of her novels that happens to have the same title as another book as a link in my chain; see also September 2020’s). Back in 2010, Erica Wagner, then literary editor of The Times and one of my idols (she’s American), happened to mention in her column the manner of death of a character in Still Life. Except she had it wrong. I e-mailed to say so, and got referred to in a follow-up column soon thereafter as a “perceptive reader” (i.e., know-it-all) who spotted the error; she used it as an opportunity to reflect on the tricksy nature of memory.

#4 Still Life is one of my favourite A.S. Byatt novels (this is not the first time I’ve used one of her novels that happens to have the same title as another book as a link in my chain; see also September 2020’s). Back in 2010, Erica Wagner, then literary editor of The Times and one of my idols (she’s American), happened to mention in her column the manner of death of a character in Still Life. Except she had it wrong. I e-mailed to say so, and got referred to in a follow-up column soon thereafter as a “perceptive reader” (i.e., know-it-all) who spotted the error; she used it as an opportunity to reflect on the tricksy nature of memory.

#5 When I wrote to Wagner, I remarked that the real means of death was similar to Thomas Merton’s, which is why it was fresh in mind though I hadn’t read the Byatt in years. (It would be ripe for rereading, in fact.) No spoilers here, so only look into Merton’s death if you’re morbidly curious and don’t mind having a novel’s ending ruined. I’ve not read an entire book by Merton yet, but have encountered his wisdom piecemeal via lots of references made by other authors and the daily excerpts in the one-year devotional book A Year with Thomas Merton, which I must have worked my way through in 2009.

#5 When I wrote to Wagner, I remarked that the real means of death was similar to Thomas Merton’s, which is why it was fresh in mind though I hadn’t read the Byatt in years. (It would be ripe for rereading, in fact.) No spoilers here, so only look into Merton’s death if you’re morbidly curious and don’t mind having a novel’s ending ruined. I’ve not read an entire book by Merton yet, but have encountered his wisdom piecemeal via lots of references made by other authors and the daily excerpts in the one-year devotional book A Year with Thomas Merton, which I must have worked my way through in 2009.

#6 Merton was a Trappist monk based in Kentucky. In the process of introducing his girlfriend, Alma, a Bosnian American who grew up in northern Virginia, to the state where she’s come to live, Owen, the protagonist of Lee Cole’s debut novel, Groundskeeping, takes her to see Merton’s grave at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, near Bardstown, Kentucky. Literary grave hunting is one of my niche hobbies, and Groundskeeping, like Our Wives Under the Sea, is one of my top novels of 2022 so far.

#6 Merton was a Trappist monk based in Kentucky. In the process of introducing his girlfriend, Alma, a Bosnian American who grew up in northern Virginia, to the state where she’s come to live, Owen, the protagonist of Lee Cole’s debut novel, Groundskeeping, takes her to see Merton’s grave at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, near Bardstown, Kentucky. Literary grave hunting is one of my niche hobbies, and Groundskeeping, like Our Wives Under the Sea, is one of my top novels of 2022 so far.

So, I’ve gone from one reading year highlight to another, via two instances of me being a book nerd. Deep sea creatures, slime and snails, accidental deaths, and literary grave spotting: it’s been an odd chain! That’s just what I happened to come up with this morning, right after I wrote my review of Groundskeeping for BookBrowse; I’d started a chain yesterday afternoon and came up with something completely different before getting stuck on link #4. It goes to show you how arbitrary and off-the-cuff this meme can be, though I know others pick a strategy and stick with it, or first choose the books and then shoehorn them in.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point is True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey. I can’t remember if I still have a copy – pretty much all of my books are now packed in advance of our mid-May move – but if I find it, I should be sure to actually read it!

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

“Today Is the Day” stands out for its fable-like setup: “Today is the day the women of our village go out along the highway planting blisterlilies.” With the ritualistic activity and the arcane language, it seems borne out of women’s secret history; if it weren’t for mentions of a few modern things like a basketball court, it could have taken place in medieval times.

“Today Is the Day” stands out for its fable-like setup: “Today is the day the women of our village go out along the highway planting blisterlilies.” With the ritualistic activity and the arcane language, it seems borne out of women’s secret history; if it weren’t for mentions of a few modern things like a basketball court, it could have taken place in medieval times. And my overall favourite, 3) “Fuel for the Fire,” a lovely festive-season story that gets beyond the everything-going-wrong-on-a-holiday stereotypes, even though the oven does play up as the narrator is trying to cook a New Year’s Day goose. The things her widowed father brings along to burn on their open fire – a shed he demolished, lilac bushes he took out because they reminded him of his late wife, bowling pins from a derelict alley – are comical yet sad at base, like so much of the story. “Other people might see something nostalgic or sad, but he took a look and saw fuel.” Fire is a force that, like time, will swallow everything.

And my overall favourite, 3) “Fuel for the Fire,” a lovely festive-season story that gets beyond the everything-going-wrong-on-a-holiday stereotypes, even though the oven does play up as the narrator is trying to cook a New Year’s Day goose. The things her widowed father brings along to burn on their open fire – a shed he demolished, lilac bushes he took out because they reminded him of his late wife, bowling pins from a derelict alley – are comical yet sad at base, like so much of the story. “Other people might see something nostalgic or sad, but he took a look and saw fuel.” Fire is a force that, like time, will swallow everything.

Basics: 11 stories, grouped under 4 mythical locales

Basics: 11 stories, grouped under 4 mythical locales Basics: 8 linked stories following 7th-grade teacher Beatrice Hempel through her twenties and thirties

Basics: 8 linked stories following 7th-grade teacher Beatrice Hempel through her twenties and thirties Basics: 18 stories, some of flash fiction length

Basics: 18 stories, some of flash fiction length

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

Our joint highest rating, and one of our best discussions – taking in mental illness and its diagnosis and treatment, marriage, childlessness, alcoholism, sisterhood, creativity, neglect, unreliable narrators and loneliness. For several of us, these issues hit close to home due to personal or family experience. We particularly noted the way that Mason sets up parallels between pairs of characters, accurately reflecting how family dynamics can be replicated in later generations.

This was a cute read about two little girls helping their father in the garden and discovering the natural wonders of the season, like tadpoles in a pond, birds building nests, and insects and worms in the compost heap. A section at the end gives more information about the science of spring – unfortunately, it mislabels one bird and includes North American species without labelling them as such, whereas the rest of the book was clearly set in the UK. The strategy reminded me of that in Wild Child by Dara McAnulty. This year is the first time a children’s book Wainwright Prize will be awarded, so we’ll see this kind of book being recognized more.

This was a cute read about two little girls helping their father in the garden and discovering the natural wonders of the season, like tadpoles in a pond, birds building nests, and insects and worms in the compost heap. A section at the end gives more information about the science of spring – unfortunately, it mislabels one bird and includes North American species without labelling them as such, whereas the rest of the book was clearly set in the UK. The strategy reminded me of that in Wild Child by Dara McAnulty. This year is the first time a children’s book Wainwright Prize will be awarded, so we’ll see this kind of book being recognized more. Encore is my last unread journal of May Sarton’s. It begins in May 1991, when she’s 79 and in recovery from major illness. She’s still plagued by pain and fatigue, but her garden and visits from friends are a solace. Although she has to lie down to garden, “to put my hands in the earth to dig is life giving … it is almost as if the earth were nourishing me at the moment.” As usual, there are lovely reflections on the freedoms as well as the losses of ageing. This book, like the previous, was dictated, so there is a bit of repetition. I’ve been amused to see how pretentious she found A.S. Byatt’s Possession! An entry or two at a sitting helped calm my mind during the stress of moving week.

Encore is my last unread journal of May Sarton’s. It begins in May 1991, when she’s 79 and in recovery from major illness. She’s still plagued by pain and fatigue, but her garden and visits from friends are a solace. Although she has to lie down to garden, “to put my hands in the earth to dig is life giving … it is almost as if the earth were nourishing me at the moment.” As usual, there are lovely reflections on the freedoms as well as the losses of ageing. This book, like the previous, was dictated, so there is a bit of repetition. I’ve been amused to see how pretentious she found A.S. Byatt’s Possession! An entry or two at a sitting helped calm my mind during the stress of moving week.

I saw it on shelf at the library and knew now was the perfect time to read My Life in Houses by Margaret Forster, a memoir via the places she’s lived, starting with the house where she was born in 1938, on a council estate in Carlisle. There’s something appealing to me about tracing a life story through homes – Paul Auster did the same in part of Winter Journal. I’d be tempted to undertake a similar exercise myself someday.

I saw it on shelf at the library and knew now was the perfect time to read My Life in Houses by Margaret Forster, a memoir via the places she’s lived, starting with the house where she was born in 1938, on a council estate in Carlisle. There’s something appealing to me about tracing a life story through homes – Paul Auster did the same in part of Winter Journal. I’d be tempted to undertake a similar exercise myself someday. The swifts come screeching down our new street and we saw one investigating a crevice in our back roof for a nest! In Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor, she is lonely in rural Ghana, where she and her husband had moved for his work, and takes in a young swift displaced from its nest. I’m only in the early pages, but can tell that her care for the bird will be a way of exploring her own feeling of displacement and the desire to belong. “Although I was unaware of it at the time, the English countryside and the birds had turned into my anchor of home.”

The swifts come screeching down our new street and we saw one investigating a crevice in our back roof for a nest! In Fledgling by Hannah Bourne-Taylor, she is lonely in rural Ghana, where she and her husband had moved for his work, and takes in a young swift displaced from its nest. I’m only in the early pages, but can tell that her care for the bird will be a way of exploring her own feeling of displacement and the desire to belong. “Although I was unaware of it at the time, the English countryside and the birds had turned into my anchor of home.” The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest)

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (back to school in the Midwest) I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf.

I’ll admit it: it was Angela Harding’s gorgeous cover illustration that drew me to this one. But I found a story that lived up to it, too. October, who has just turned 11 and is named after her birth month, lives in the woods with her father. Their shelter and their ways are fairly primitive, but it’s what October knows and loves. When her father has an accident and she’s forced into joining her mother’s London life, her only consolations are her rescued barn owl chick, Stig, and the mudlarking hobby she takes up with her new friend, Yusuf. The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)

The second in the quartet of seasonal “Brambly Hedge” stories. Autumn is a time for stocking the pantry shelves with preserves, so the mice are out gathering berries, fruit and mushrooms. Young Primrose wanders off, inadvertently causing alarm – though all she does is meet a pair of elderly harvest mice and stay for tea and cake in their round nest amid the cornstalks. I love all the little touches in the illustrations: the patchwork tea cosy matches the quilt on the bed one floor up, and nearly every page is adorned with flowers and other foliage. After we get past the mild peril that seems to be de rigueur for any children’s book, all is returned to a comforting normal. Time to get the Winter volume out from the library. (Public library)  The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)

The first whole book I’ve read in French in many a year. I just about coped, given that it’s a picture book with not all that many words on a page; any vocabulary I didn’t know offhand, I could understand in context. It’s late into the autumn and Papa Bear is ready to start hibernating for the year, but Little Bear spies a late-flying bee and follows it out of the woods and all the way to the big city. Papa Bear, realizing his lad isn’t beside him in the cave, sets out in pursuit and bee, cub and bear all end up at the opera hall, to the great surprise of the audience. What will Papa do with his moment in the spotlight? This is a lovely book that, despite the whimsy, still teaches about the seasons and parent–child bonds as it offers a vision of how humans and animals could coexist. I’ve since found out that this was made into a series of four books, all available in English translation. (Little Free Library)  This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

This YA graphic novel is set on a Nebraska pumpkin patch that’s more like Disney World than a simple field down the road. Josiah and Deja have worked together at the Succotash Hut for the last three autumns. Today they’re aware that it’s their final Halloween before leaving for college. Deja’s goal is to try every culinary delicacy the patch has to offer – a smorgasbord of foodstuffs that are likely to be utterly baffling to non-American readers: candy apples, Frito pie (even I hadn’t heard of this one), kettle corn, s’mores, and plenty of other saccharine confections.

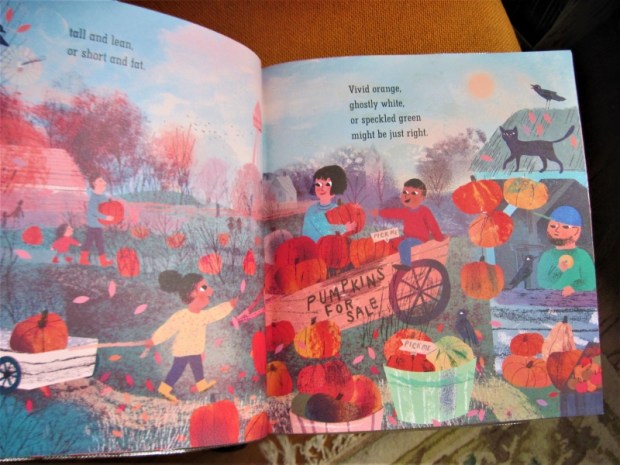

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)

From picking the best pumpkin at the patch to going out trick-or-treating, this is a great introduction to Halloween traditions. It even gives step-by-step instructions for carving a jack-o’-lantern. The drawing style – generally 2D, and looking like it could be part cut paper collages, with some sponge painting – reminds me of Ezra Jack Keats and most of the characters are not white, which is refreshing. There are lots of little autumnal details to pick out in the two-page spreads, with a black cat and crows on most pages and a set of twins and a mouse on some others. The rhymes are either in couplets or ABCB patterns. Perfect October reading. (Public library)  Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?

Any super-autumnal reading for you this year?

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also

A debut trio of raw stories set in the Yorkshire countryside. In “Offcomers,” the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak threatens the happiness of a sheep-farming couple. The effects of rural isolation on a relationship resurface in “Outside Are the Dogs.” In “Cull Yaw,” a vegetarian gets involved with a butcher who’s keen on marketing mutton and ends up helping him with a grisly project. This was the stand-out for me. I appreciated the clear-eyed look at where food comes from. At the same time, narrator Star’s mother is ailing: a reminder that decay is inevitable and we are all naught but flesh and blood. I liked the prose well enough, but found the characterization a bit thin. One for readers of Andrew Michael Hurley and Cynan Jones. (See also  Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins.

Okorie emigrated from Nigeria to Ireland in 2005. Her time living in a direct provision hostel for asylum seekers informed the title story about women queuing for and squabbling over food rations, written in an African pidgin. In “Under the Awning,” a Black woman fictionalizes her experiences of racism into a second-person short story her classmates deem too bleak. The Author’s Note reveals that Okorie based this one on comments she herself got in a writers’ group. “The Egg Broke” returns to Nigeria and its old superstition about twins. This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after

This is the third time Simpson has made it into one of my September features (after  Sara has made a new life for herself in Dublin, with a boyfriend and an avocado tree. She rarely thinks about her past in Bosnia or hears her mother tongue. It’s a rude awakening, then, when she gets a phone call from her childhood best friend, Lejla Begić. Her bold, brassy pal says she needs Sara to pick her up in Mostar and drive her to Vienna to find her brother, Armin. No matter that Sara and Lejla haven’t been in contact in 12 years. But Lejla still has such a hold over Sara that she books a plane ticket right away.

Sara has made a new life for herself in Dublin, with a boyfriend and an avocado tree. She rarely thinks about her past in Bosnia or hears her mother tongue. It’s a rude awakening, then, when she gets a phone call from her childhood best friend, Lejla Begić. Her bold, brassy pal says she needs Sara to pick her up in Mostar and drive her to Vienna to find her brother, Armin. No matter that Sara and Lejla haven’t been in contact in 12 years. But Lejla still has such a hold over Sara that she books a plane ticket right away.

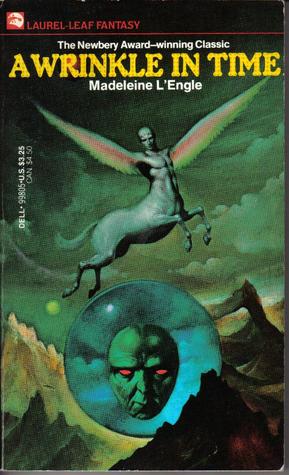

I probably picked this up at age seven or so as a natural follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia – both are well-regarded children’s sci fi/fantasy from an author with a Christian worldview. In my memory I didn’t connect with L’Engle’s work particularly well, finding it vague and cerebral, if creative, compared to Lewis’s. I don’t think I ever went on to the multiple sequels. As an adult I’ve enjoyed L’Engle’s autobiographical and spiritual writing, especially the Crosswicks Journals, so I thought I’d give her best-known book another try.

I probably picked this up at age seven or so as a natural follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia – both are well-regarded children’s sci fi/fantasy from an author with a Christian worldview. In my memory I didn’t connect with L’Engle’s work particularly well, finding it vague and cerebral, if creative, compared to Lewis’s. I don’t think I ever went on to the multiple sequels. As an adult I’ve enjoyed L’Engle’s autobiographical and spiritual writing, especially the Crosswicks Journals, so I thought I’d give her best-known book another try.

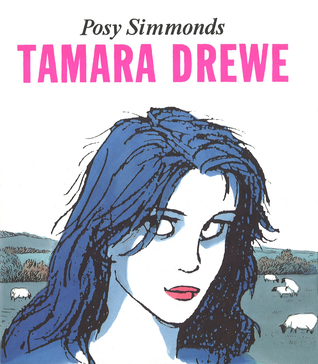

Simmonds recreates the central situation of FFTMC – an alluring young woman returns to her ancestral village and enraptures three very different men – but doesn’t stick slavishly to its plot. Her greatest innovation is in the narration. Set in and around a writers’ retreat, the novel is told in turns by Dr. Glen Larson, a (chubby, Bryson-esque) visiting American academic trying to get to grips with his novel; Beth Hardiman, who runs the retreat center and does all the admin for her philandering crime writer husband, Nicholas; and Casey Shaw, a lower-class teenager who, with her bold pal Jody, observes all the goings-on among the posh folk from the local bus shelter and later gets unexpectedly drawn in to their lives.

Simmonds recreates the central situation of FFTMC – an alluring young woman returns to her ancestral village and enraptures three very different men – but doesn’t stick slavishly to its plot. Her greatest innovation is in the narration. Set in and around a writers’ retreat, the novel is told in turns by Dr. Glen Larson, a (chubby, Bryson-esque) visiting American academic trying to get to grips with his novel; Beth Hardiman, who runs the retreat center and does all the admin for her philandering crime writer husband, Nicholas; and Casey Shaw, a lower-class teenager who, with her bold pal Jody, observes all the goings-on among the posh folk from the local bus shelter and later gets unexpectedly drawn in to their lives. I’ve long considered A.S. Byatt a favorite author, and early last year

I’ve long considered A.S. Byatt a favorite author, and early last year