Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

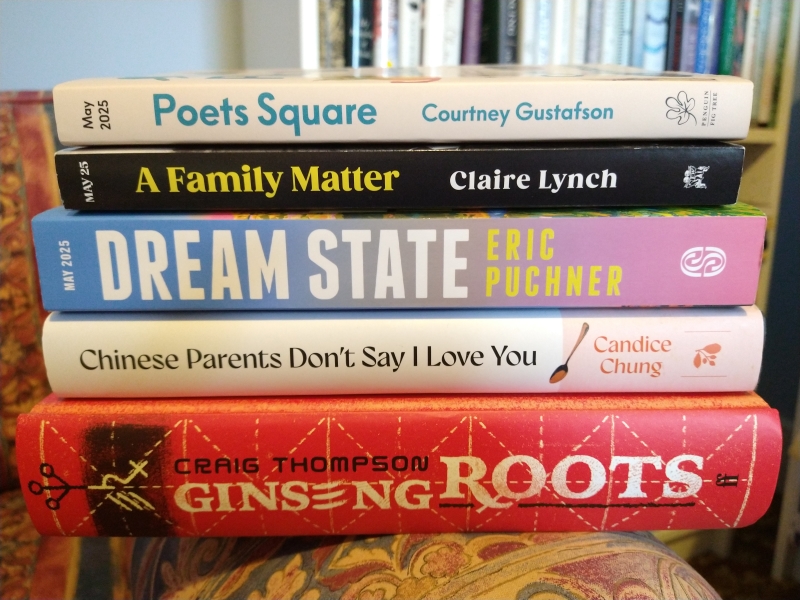

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

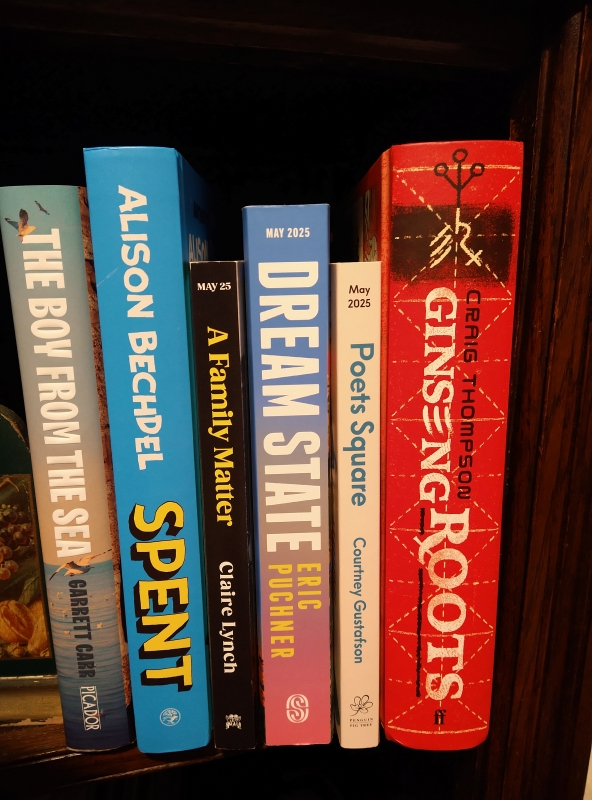

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

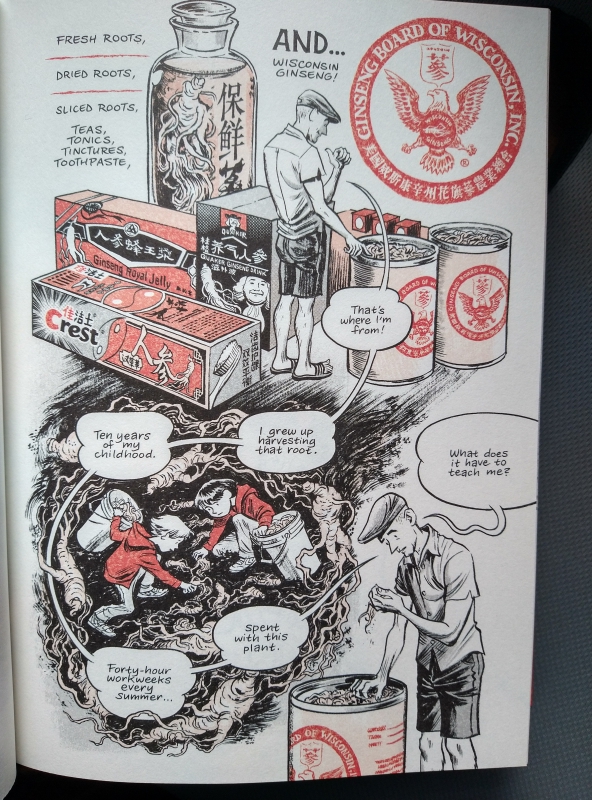

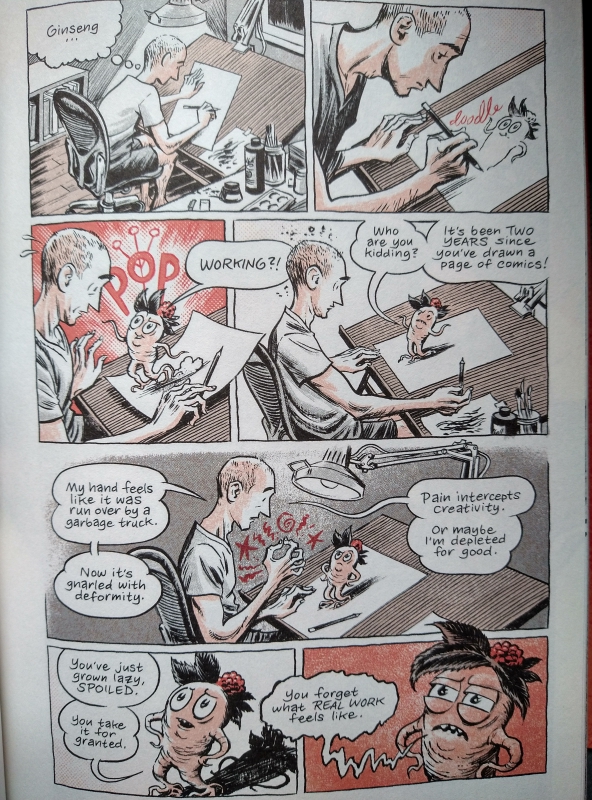

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Three May Graphic Novel Releases: Orwell, In, and Coma

These three terrific graphic novels all have one-word titles and were published on the 13th of May. Outwardly, they are very different: a biography of a famous English writer, the story of an artist looking for authentic connections, and a memoir of a medical crisis that had permanent consequences. The drawing styles are varied as well. But if the books share one thing, it’s an engagement with loneliness: It’s tempting to see the self as being pitted against the world, with illness an additional isolating force, but family, friends and compatriots are there to help us feel less alone and like we are a part of something constructive.

Orwell by Pierre Christin; illustrated by Sébastien Verdier

[Translated from the French by Edward Gauvin]

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

George Orwell was born Eric Blair in Bengal, where his father worked for the colonial government. As a boy, he loved science fiction and knew that he would become a writer. He had an unhappy time at prep school, where he was on reduced fees, and proceeded to Eton and then police training in Burma. Already he felt that “imperialism was an evil thing.” Among this book’s black-and-white panes, the splashes of colour – blood, a British flag – stand out, and guest artists contribute a two-page colour spread each, illustrating scenes from Orwell’s major works. His pen name commemorates a local river and England’s patron saint, marking his preoccupation with the essence of Englishness: something deeper than his hated militarism and capitalism. Even when he tried to ‘go native’ for embedded journalism (Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier), his accent marked him out as posh. He was opinionated and set out “rules” for clear writing and the proper making of tea.

The book’s settings range from Spain, where Orwell went to fight in the Civil War, via a bomb shelter in London’s Underground, to the island of Jura, where he retired after the war. I particularly loved the Scottish scenery. I also appreciated the notes on where his life story entered into his fiction (especially in A Clergyman’s Daughter and Keep the Aspidistra Flying). During World War II he joined the Home Guard and contributed to BBC broadcasting alongside T.S. Eliot. He had married Eileen, adopted a baby boy, and set up a smallholding. Even when hospitalized for tuberculosis, he wouldn’t stop typing (or smoking).

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

Christin creates just enough scenes to give a sense of the sweep of Orwell’s life, and incorporates plenty of the author’s own words in a typewriter font. He recognizes all the many aspects, sometimes contradictory, of his subject’s life. And in an afterword, he makes a strong case for Orwell’s ideas being more important now than ever before. My knowledge of Orwell’s oeuvre, apart from the ones everyone has read – Animal Farm and 1984 – is limited; luckily this is suited not just to Orwell fans but to devotees of life stories of any kind.

With thanks to SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

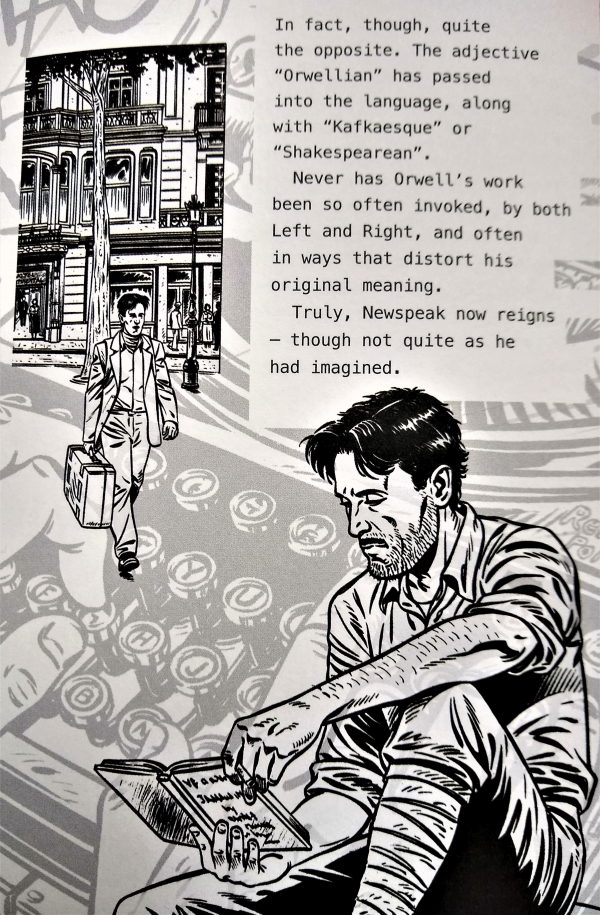

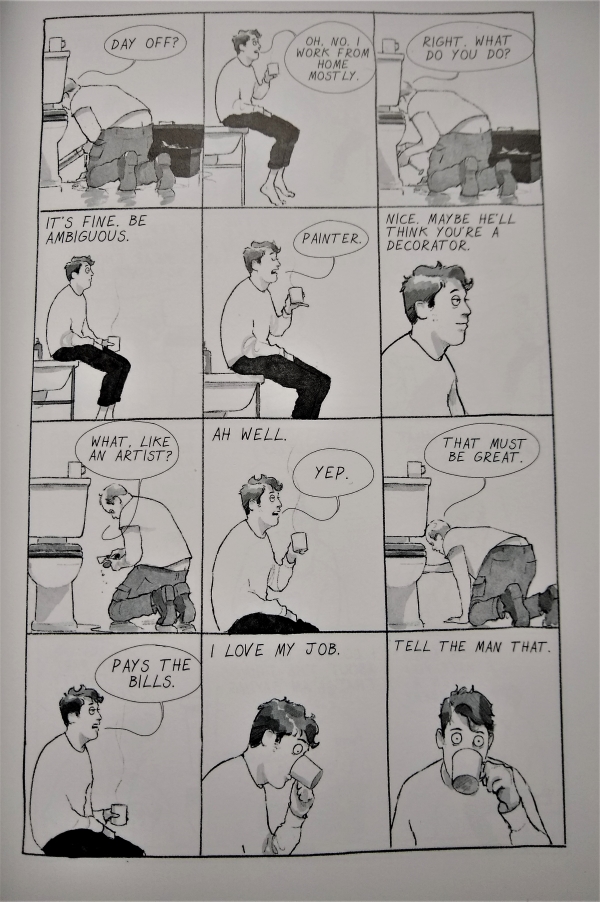

In by Will McPhail

Nick never knows the right thing to say. The bachelor artist’s well-intentioned thoughts remain unvoiced, such that all he can manage is small talk. Whether he’s on a subway train, interacting with his mom and sister, or sitting in a bar with a tongue-in-cheek name (like “Your Friends Have Kids” or “Gentrificchiato”), he’s conscious of being the clichéd guy who’s too clueless or pathetic to make a real connection with another human being. That starts to change when he meets Wren, a Black doctor who instantly sees past all his pretence.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Like Orwell, In makes strategic use of colour spreads. “Say something that matters,” Nick scolds himself, and on the rare occasions when he does figure out what to say or ask – the magic words that elicit an honest response – it’s as if a new world opens up. These full-colour breakthrough scenes are like dream sequences, filled with symbols such as a waterfall, icy cliff, or half-submerged building with classical façade. Each is heralded by a close-up image on the other person’s eyes: being literally close enough to see their eye colour means being metaphorically close enough to be let in. Nick achieves these moments with everyone from the plumber to his four-year-old nephew.

Alternately laugh-out-loud funny and tender, McPhail’s debut novel is as hip as it is genuine. It’s a spot-on picture of modern life in a generic city. I especially loved the few pages when Nick is on a Zoom call with carefully ironed shirt but no trousers and the potential employers on the other end get so lost in their own jargon that they forget he’s there. His banter with Wren or with his sister reveals a lot about these characters, but there’s also an amazing 12-page wordless sequence late on that conveys so much. While I’d recommend this to readers of Alison Bechdel, Craig Thompson, and Chris Ware (and expect it to have a lot in common with Kristen Radtke’s forthcoming Seek You: A Journey through American Loneliness), it’s perfect for those brand new to graphic novels, too – a good old-fashioned story, with all the emotional range of Writers & Lovers. I hope it’ll be a wildcard entry on the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist.

With thanks to Sceptre for the free copy for review.

Coma by Zara Slattery

In May 2013, Zara Slattery’s life changed forever. What started as a nagging sore throat developed into a potentially deadly infection called necrotising fascitis. She spent 15 days in a medically induced coma and woke up to find that one of her legs had been amputated. As in Orwell and In, colour is used to differentiate different realms. Monochrome sketches in thick crayon illustrate her husband Dan’s diary of the everyday life that kept going while she was in hospital, yet it’s the coma/fantasy pages in vibrant blues, reds and gold that feel more real.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Slattery remembers, or perhaps imagines, being surrounded by nightmarish skulls and menacing animals. She feels accused and guilty, like she has to justify her continued existence. In one moment she’s a puppet; in another she’s in ancient China, her fate being decided for her. Some of the watery landscapes and specific images here happen to echo those in McPhail’s novel: a splash park, a sunken theatre; a statue on a plinth. There’s also a giant that reminded me a lot of one of the monsters in Spirited Away.

Meanwhile, Dan was holding down the fort, completing domestic tasks and reassuring their three children. Relatives came to stay; neighbours brought food, ran errands, and gave him lifts to the hospital. He addresses the diary directly to Zara as a record of the time she spent away from home and acknowledges that he doesn’t know if she’ll come back to them. A final letter from Zara’s nurse reveals how bad off she was, maybe more so than Dan was aware.

This must have been such a distressing time to revisit. In this interview, Slattery talks about the courage it took to read Dan’s diary even years after the fact. I admired how the book’s contrasting drawing styles recreate her locked-in mental state and her family’s weeks of waiting – both parties in limbo, wondering what will come next.

Brighton, where Slattery is based, is a hotspot of the Graphic Medicine movement spearheaded by Ian Williams (author of The Lady Doctor). Regular readers know how much I love health narratives, and with my keenness for graphic novels this series couldn’t be better suited to my interests.

With thanks to Myriad Editions for the free copy for review.

Read any graphic novels recently?

Spinning by Tillie Walden (A Graphic Memoir)

I’m uncomfortable with the term “graphic memoir,” which to me connotes a memoir with graphically violent or sexual content. However, it seems to be accepted parlance nowadays for a graphic novel that’s autobiographical rather than fictional. Tillie Walden’s Spinning is in the same vein as Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Craig Thompson’s Blankets: a touching coming-of-age story delivered through the medium of comics.

Specifically, this is about the 12 years Walden spent in the competitive figure skating world. She grew up in New Jersey, and when the family moved to Austin, Texas the bullying she’d experienced in her previous school continued. Mornings started at 4 a.m. when she got up for individual skating lessons; after school she had synchronized skating practice at another rink.

Specifically, this is about the 12 years Walden spent in the competitive figure skating world. She grew up in New Jersey, and when the family moved to Austin, Texas the bullying she’d experienced in her previous school continued. Mornings started at 4 a.m. when she got up for individual skating lessons; after school she had synchronized skating practice at another rink.

These years were full of cello lessons, unrequited crushes and skating competitions she rode to with her friend Lindsay and Lindsay’s mother. The femininity of the skating world – the slicked-back buns and thick make-up; the way every girl was made to look the same – chafed with Walden because she’d known since age five that she was gay. All told, she was disillusioned with what once seemed like her whole life:

Skating changed when I came to Texas. It wasn’t strict or beautiful or energizing any more. Now it just felt dull and exhausting. I couldn’t understand why I should keep skating after it lost all its shine.

Every chapter is named after a different skating move: waltz jump, axel, camel spin, etc. Walden’s drawing style initially reminded me most of This One Summer by Jillian and Mariko Tamaki, which is also about teens finding their way in the world and shares the same mostly purple and gray coloring. Walden’s work is more sketch-like, and also includes yellow on certain pages. The last third or so of the book is the most momentous: between when Walden comes out at 15 and when she gives up skating at 17.

Believe it or not, Walden was born in 1996 and this is her fourth book. She’s already won two Ignatz Awards. I felt this book would have benefited from more hindsight: time to mull over her skating experience and figure out what it all meant. The Author’s note at the end struck me as particularly shallow, like this project was about quick catharsis rather than considered reflection. However, the book’s scope (nearly 400 pages) is impressive, and Walden is adept at capturing the emotional milestones of her early life.

Published in the UK on September 12th. With thanks to Paul Smith of SelfMadeHero – celebrating its 10th anniversary this year – for the free copy for review.

My rating:

Reviews Roundup, March–April

One of my goals with this blog was to have one convenient place where I could gather together all my writing that appears in disparate online locations. To that end, once a month I provide links to all book reviews I’ve published elsewhere, with a rating (below each description) and a taster so you can decide whether to read more. A few exceptions: I don’t point out my Kirkus Indie, BlueInk or Publishers Weekly reviews since I don’t get a byline.

The Bookbag

The Improbability of Love by Hannah Rothschild: From the Baileys Prize longlist, an enchanting debut novel that blends art and cooking, mystery and romance. Annie McDee, a heartbroken PA and amateur chef, pays £75 for a painting from a junk shop, not realizing it’s a lost Watteau that will spark bidding wars and uncover a sordid chapter of history. In a triumph of playful narration, we mostly learn about the artwork’s history from the painting ‘herself’. She recounts her turbulent 300-year-history and lists her many illustrious owners, including Marie Antoinette, Napoleon and Queen Victoria. These are the novel’s only first-person sections; you can just imagine a voiceover from Helen Mirren or Judi Dench.

The Improbability of Love by Hannah Rothschild: From the Baileys Prize longlist, an enchanting debut novel that blends art and cooking, mystery and romance. Annie McDee, a heartbroken PA and amateur chef, pays £75 for a painting from a junk shop, not realizing it’s a lost Watteau that will spark bidding wars and uncover a sordid chapter of history. In a triumph of playful narration, we mostly learn about the artwork’s history from the painting ‘herself’. She recounts her turbulent 300-year-history and lists her many illustrious owners, including Marie Antoinette, Napoleon and Queen Victoria. These are the novel’s only first-person sections; you can just imagine a voiceover from Helen Mirren or Judi Dench.

Max Gate by Damien Wilkins: This is a novel of Thomas Hardy’s last days, but we get an unusual glimpse into his household at Max Gate, Dorchester through the point-of-view of his housemaid, twenty-six-year-old Nellie Titterington. Ultimately I suspect a third-person omniscient voice would have worked better. In fact, some passages – recounting scenes Nellie is not witness to – are in the third person, which felt a bit like cheating. Fans familiar with the excellent Claire Tomalin biography might not learn much about Hardy and his household dynamics, but it was fun to spend some imaginary time at a place I once visited. [First published in New Zealand in 2013; releases in the US and UK on June 6th.]

Max Gate by Damien Wilkins: This is a novel of Thomas Hardy’s last days, but we get an unusual glimpse into his household at Max Gate, Dorchester through the point-of-view of his housemaid, twenty-six-year-old Nellie Titterington. Ultimately I suspect a third-person omniscient voice would have worked better. In fact, some passages – recounting scenes Nellie is not witness to – are in the third person, which felt a bit like cheating. Fans familiar with the excellent Claire Tomalin biography might not learn much about Hardy and his household dynamics, but it was fun to spend some imaginary time at a place I once visited. [First published in New Zealand in 2013; releases in the US and UK on June 6th.]

Dust by Michael Marder: A philosopher carries out an interdisciplinary study of dust: what it’s made of, what it means, and how it informs our metaphors. In itself, he points out, dust is neither positive nor negative, but we give it various cultural meanings. In the Bible, it is the very substance of mortality. Meanwhile “The war on dust, a hallmark of modern hygiene, reverberates with the political hygiene of the war on terror.” The contemporary profusion of allergies may, in fact, be an unintended consequence of our crusade against dust. The discussion is pleasingly wide-ranging, with some unexpected diversions – such as the metaphorical association between ‘stardust’ and celebrity – but also some impenetrable jargon. I’d be interested to try other titles from Bloomsbury’s “Object Lessons” series.

Dust by Michael Marder: A philosopher carries out an interdisciplinary study of dust: what it’s made of, what it means, and how it informs our metaphors. In itself, he points out, dust is neither positive nor negative, but we give it various cultural meanings. In the Bible, it is the very substance of mortality. Meanwhile “The war on dust, a hallmark of modern hygiene, reverberates with the political hygiene of the war on terror.” The contemporary profusion of allergies may, in fact, be an unintended consequence of our crusade against dust. The discussion is pleasingly wide-ranging, with some unexpected diversions – such as the metaphorical association between ‘stardust’ and celebrity – but also some impenetrable jargon. I’d be interested to try other titles from Bloomsbury’s “Object Lessons” series.

Foreword Reviews

How to Cure Bedwetting by Lane Robson (Oh, the interesting topics my work with self-published books introduces me to!): Explaining the anatomical and behavioral reasons behind bedwetting, the Calgary-based physician gives practical tips for curing the problem within six to twelve months. Throughout, the text generally refers to “pee” and “poop,” which detracts slightly from the professionalism of the work. All the same, this compendium of knowledge, drawing as it does on the author’s forty years of experience, should answer every possible question on the subject. Highly recommended to parents of younger elementary school children, this book will be an invaluable reference in tackling bedwetting.

Nudge

The Prophets of Eternal Fjord by Kim Leine: An epic novel about an unconventional priest, set in late-eighteenth-century Denmark and Greenland. This struck me as a cross between Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned, another historical saga from Denmark and one of my favorite novels of all time, and Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. Like the former, it features perilous sea voyages and ambivalent father–son relationships; like the latter, it’s edgy and sexualized, full of lechery and bodily fluids. No airbrushing the more unpleasant aspects of history here. The entire story is told in the present tense, with no speech marks. It took me nearly a month and a half to read; by the end I felt I’d been on an odyssey as long and winding as Morten’s.

The Prophets of Eternal Fjord by Kim Leine: An epic novel about an unconventional priest, set in late-eighteenth-century Denmark and Greenland. This struck me as a cross between Carsten Jensen’s We, the Drowned, another historical saga from Denmark and one of my favorite novels of all time, and Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White. Like the former, it features perilous sea voyages and ambivalent father–son relationships; like the latter, it’s edgy and sexualized, full of lechery and bodily fluids. No airbrushing the more unpleasant aspects of history here. The entire story is told in the present tense, with no speech marks. It took me nearly a month and a half to read; by the end I felt I’d been on an odyssey as long and winding as Morten’s.

PANK

Still the Animals Enter by Jane Hilberry: A rich, strange, and gently erotic collection featuring diverse styles and blurring the lines between child and adult, human and animal, life and death through the language of metamorphosis. Ambivalence about the moments of transition between childhood and adulthood infuses Part One. Early on, “A Hole in the Fence” finishes on a whispered offer: “You could be part of this.” The message in this resonant collection, though, is that we already are a part of it: part of a shared life that moves beyond the individual family or even the human species. We are all connected—to the children we once were, to lovers and family members lost and found, and to the animals we watch in wonder.

Still the Animals Enter by Jane Hilberry: A rich, strange, and gently erotic collection featuring diverse styles and blurring the lines between child and adult, human and animal, life and death through the language of metamorphosis. Ambivalence about the moments of transition between childhood and adulthood infuses Part One. Early on, “A Hole in the Fence” finishes on a whispered offer: “You could be part of this.” The message in this resonant collection, though, is that we already are a part of it: part of a shared life that moves beyond the individual family or even the human species. We are all connected—to the children we once were, to lovers and family members lost and found, and to the animals we watch in wonder.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Relief Map by Rosalie Knecht: Lomath, Pennsylvania consists of a half-mile stretch between old textile mills and is home to just 150 people. During one unpredictable summer, blackouts and the arrival of an Eastern European fugitive draw the residents into a welter of paranoia and misguided choices. Our eyewitness to provincial commotion is 16-year-old Livy Marko, who considers herself plain and awkward – her childhood style was supplied by Anne of Green Gables and Goodwill. Knecht’s writing is marked by carefully chosen images and sounds. The novel maintains a languid yet subtly tense ambience. For Livy, coming of age means realizing actions always have consequences. Offbeat and atmospheric, this debut is probably too quiet to make a major splash, but has its gentle rewards.

Relief Map by Rosalie Knecht: Lomath, Pennsylvania consists of a half-mile stretch between old textile mills and is home to just 150 people. During one unpredictable summer, blackouts and the arrival of an Eastern European fugitive draw the residents into a welter of paranoia and misguided choices. Our eyewitness to provincial commotion is 16-year-old Livy Marko, who considers herself plain and awkward – her childhood style was supplied by Anne of Green Gables and Goodwill. Knecht’s writing is marked by carefully chosen images and sounds. The novel maintains a languid yet subtly tense ambience. For Livy, coming of age means realizing actions always have consequences. Offbeat and atmospheric, this debut is probably too quiet to make a major splash, but has its gentle rewards.

Shiny New Books

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot: Put simply, this is a memoir about Amy Liptrot’s slide into alcoholism and her subsequent recovery. Liptrot grew up on mainland Orkney, a tight-knit Scottish community she was eager to leave as a teenager but found herself returning to a decade later, washed up after the dissolute living and heartbreak she left behind in London. A simple existence, close to nature and connected to other people, was just what she needed during her first two years of sobriety. Her atmospheric writing about the magical Orkney Islands and their wildlife, rather than the slightly clichéd ruminating on alcoholism, is what sets the book apart. (On the Wellcome Prize shortlist.)

The Outrun by Amy Liptrot: Put simply, this is a memoir about Amy Liptrot’s slide into alcoholism and her subsequent recovery. Liptrot grew up on mainland Orkney, a tight-knit Scottish community she was eager to leave as a teenager but found herself returning to a decade later, washed up after the dissolute living and heartbreak she left behind in London. A simple existence, close to nature and connected to other people, was just what she needed during her first two years of sobriety. Her atmospheric writing about the magical Orkney Islands and their wildlife, rather than the slightly clichéd ruminating on alcoholism, is what sets the book apart. (On the Wellcome Prize shortlist.)

I also post reviews of most of my casual reading and skimming on Goodreads:

Look We Have Coming to Dover! by Daljit Nagra: The dialect was a bit too heavy for me in some of these poems about the Sikh experience in Britain. By far my favorite was “In a White Town,” which opens: “She never looked like other boys’ mums. / No one ever looked without looking again / at the pink kameez and balloon’d bottoms, // mustard-oiled trail of hair, brocaded pink / sandals and the smell of curry. That’s why / I’d bin the letters about Parents’ Evenings …”

Look We Have Coming to Dover! by Daljit Nagra: The dialect was a bit too heavy for me in some of these poems about the Sikh experience in Britain. By far my favorite was “In a White Town,” which opens: “She never looked like other boys’ mums. / No one ever looked without looking again / at the pink kameez and balloon’d bottoms, // mustard-oiled trail of hair, brocaded pink / sandals and the smell of curry. That’s why / I’d bin the letters about Parents’ Evenings …”

Work Like Any Other by Virginia Reeves: Between the blurb and the first paragraph, you already know everything that’s going to happen. I admire books that can keep you reading with interest even though you know exactly what’s coming, but this isn’t really one of those. Ultimately I would have preferred for the whole novel, rather than just alternating chapters, to be in Roscoe’s first-person voice, set wholly in prison (where he helps out in the library and with the guard dogs) but with brief flashbacks to his electricity siphoning and the circumstances of his manslaughter conviction. The writing is entirely capable, but the structure made it so I felt the story wasn’t worth my time.

Work Like Any Other by Virginia Reeves: Between the blurb and the first paragraph, you already know everything that’s going to happen. I admire books that can keep you reading with interest even though you know exactly what’s coming, but this isn’t really one of those. Ultimately I would have preferred for the whole novel, rather than just alternating chapters, to be in Roscoe’s first-person voice, set wholly in prison (where he helps out in the library and with the guard dogs) but with brief flashbacks to his electricity siphoning and the circumstances of his manslaughter conviction. The writing is entirely capable, but the structure made it so I felt the story wasn’t worth my time.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. Flashbacks to the late 1920s bring an uncomfortable racial subtext to the surface, suggesting that the Toneybee has been involved in dodgy anthropological research over the decades. This is a deep and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions. I much preferred it to We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves.

We Love You, Charlie Freeman by Kaitlyn Greenidge: The Freemans are raising Charlie, a chimpanzee, as part of their family for a Toneybee Institute experiment and teaching him to communicate via sign language. Flashbacks to the late 1920s bring an uncomfortable racial subtext to the surface, suggesting that the Toneybee has been involved in dodgy anthropological research over the decades. This is a deep and unsettling story of human–human interactions, even more so than human–animal interactions. I much preferred it to We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves.

Love Like Salt by Helen Stevenson: Stevenson’s daughter Clara has cystic fibrosis, so I approached and enjoyed this as an illness memoir. However, it’s very scattered, with lots of seemingly irrelevant material included simply because it happened to the author: her mother’s dementia, their life in France, her work as a translator and her hobby of playing the piano, her older husband’s love for Italy and Italian literature, etc. Really the central drama is their seemingly idyllic life in France, Clara being bullied there, and the decision to move back to England (near Bristol), where the girls would attend a Quaker school on scholarships and Clara was enrolled in a widespread clinical trial with modest success. Enjoyable enough if you share some of the author’s interests.

Love Like Salt by Helen Stevenson: Stevenson’s daughter Clara has cystic fibrosis, so I approached and enjoyed this as an illness memoir. However, it’s very scattered, with lots of seemingly irrelevant material included simply because it happened to the author: her mother’s dementia, their life in France, her work as a translator and her hobby of playing the piano, her older husband’s love for Italy and Italian literature, etc. Really the central drama is their seemingly idyllic life in France, Clara being bullied there, and the decision to move back to England (near Bristol), where the girls would attend a Quaker school on scholarships and Clara was enrolled in a widespread clinical trial with modest success. Enjoyable enough if you share some of the author’s interests.

Springtime: A Ghost Story by Michelle de Kretser: Ghost story? Really? There’s very little in the way of suspense, and not too much plot either, in this Australia-set novella. I would expect tension to linger and questions to remain unanswered. Instead, the author exposes Frances’s ‘ghost’ as harmless. What I think de Kretser is trying to do here is show that ghosts can be people we have known and loved or, alternatively, places we have left behind. There is some nice descriptive writing (e.g. “three staked camellias stood as whitely upright as martyrs”), but not enough story to hold the interest.

Springtime: A Ghost Story by Michelle de Kretser: Ghost story? Really? There’s very little in the way of suspense, and not too much plot either, in this Australia-set novella. I would expect tension to linger and questions to remain unanswered. Instead, the author exposes Frances’s ‘ghost’ as harmless. What I think de Kretser is trying to do here is show that ghosts can be people we have known and loved or, alternatively, places we have left behind. There is some nice descriptive writing (e.g. “three staked camellias stood as whitely upright as martyrs”), but not enough story to hold the interest.

Let the Empire Down by Alexandra Oliver: This debut collection is heavily inspired by history and travel, as well as Serbian poetry and personal anecdote. I enjoyed the earlier poems, especially the ones with ABAB or ABBA rhyme schemes. My favorite was “Plans,” about a twenty-something manicurist who abandoned her talent for science to get ready cash: “A girl’s future should be full and bright, a marble, / but (alas for her) there is a catch: / we take on the immediate. Hope flags: / wishing to be wise and come out shining, / we pop a beaker over our own flame. / We do it cheerfully. We do it coldly.” The last quarter is devoted to poems about films, especially Italian cinema.

Let the Empire Down by Alexandra Oliver: This debut collection is heavily inspired by history and travel, as well as Serbian poetry and personal anecdote. I enjoyed the earlier poems, especially the ones with ABAB or ABBA rhyme schemes. My favorite was “Plans,” about a twenty-something manicurist who abandoned her talent for science to get ready cash: “A girl’s future should be full and bright, a marble, / but (alas for her) there is a catch: / we take on the immediate. Hope flags: / wishing to be wise and come out shining, / we pop a beaker over our own flame. / We do it cheerfully. We do it coldly.” The last quarter is devoted to poems about films, especially Italian cinema.

Vinegar Girl by Anne Tyler: This is the most fun I’ve had with the Hogarth Shakespeare series so far, as well as my favorite of the three Anne Tyler novels I’ve read. Yes, it’s set in Baltimore. Kate Battista, the utterly tactless preschool assistant, kept cracking me up. Her father, an autoimmune researcher, schemes for her to marry his lab assistant, Pyotr, so he can stay in the country after his visa expires. The plot twists of the final quarter felt a little predictable, but I was won over by the good-natured storytelling and prickly heroine. (I don’t know The Taming of the Shrew well enough to comment on how this functions as a remake.) Releases in June.

Vinegar Girl by Anne Tyler: This is the most fun I’ve had with the Hogarth Shakespeare series so far, as well as my favorite of the three Anne Tyler novels I’ve read. Yes, it’s set in Baltimore. Kate Battista, the utterly tactless preschool assistant, kept cracking me up. Her father, an autoimmune researcher, schemes for her to marry his lab assistant, Pyotr, so he can stay in the country after his visa expires. The plot twists of the final quarter felt a little predictable, but I was won over by the good-natured storytelling and prickly heroine. (I don’t know The Taming of the Shrew well enough to comment on how this functions as a remake.) Releases in June.

The Assistants by Camille Perri: At age 30, Tina Fontana has been a PA to media mogul Robert Barlow for six years. He’s worth millions; she lives in a tiny Brooklyn apartment. One day a mix-up in refunding expenses lands her with a check for $19,147. If she cashes it she can pay off her debts once and for all and no one at Titan Corporation will be any the wiser, right? This is a fun and undemanding read that will probably primarily appeal to young women. I would particularly recommend it to readers of Friendship by Emily Gould and A Window Opens by Elisabeth Egan. Releases May 3rd.

The Assistants by Camille Perri: At age 30, Tina Fontana has been a PA to media mogul Robert Barlow for six years. He’s worth millions; she lives in a tiny Brooklyn apartment. One day a mix-up in refunding expenses lands her with a check for $19,147. If she cashes it she can pay off her debts once and for all and no one at Titan Corporation will be any the wiser, right? This is a fun and undemanding read that will probably primarily appeal to young women. I would particularly recommend it to readers of Friendship by Emily Gould and A Window Opens by Elisabeth Egan. Releases May 3rd.

Carnet de Voyage by Craig Thompson: A sketchbook Thompson kept on his combined European book tour for Blankets and research trip for Habibi in March–May 2004. It doesn’t really work as a stand-alone graphic memoir because there isn’t much of a narrative, just a series of book signings, random encounters with friends and strangers, and tourism. My favorite two-page spread is about a camel ride he took into the Moroccan desert. I could also sympathize with his crippling hand pain (from all that drawing) and his “chaos tolerance” overload from the stress of travel.

Carnet de Voyage by Craig Thompson: A sketchbook Thompson kept on his combined European book tour for Blankets and research trip for Habibi in March–May 2004. It doesn’t really work as a stand-alone graphic memoir because there isn’t much of a narrative, just a series of book signings, random encounters with friends and strangers, and tourism. My favorite two-page spread is about a camel ride he took into the Moroccan desert. I could also sympathize with his crippling hand pain (from all that drawing) and his “chaos tolerance” overload from the stress of travel.

Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place by Philip Marsden: Some very nice writing indeed, but not much of a storyline. The book is something of a jumble of mythology, geology, prehistory, and more recent biographical information about some famous Cornish residents, overlaid on a gentle travel memoir. I enjoyed learning about the meanings of Cornish place names, in particular, and spotting locations I’ve visited.

Rising Ground: A Search for the Spirit of Place by Philip Marsden: Some very nice writing indeed, but not much of a storyline. The book is something of a jumble of mythology, geology, prehistory, and more recent biographical information about some famous Cornish residents, overlaid on a gentle travel memoir. I enjoyed learning about the meanings of Cornish place names, in particular, and spotting locations I’ve visited.

And my highest recommendation goes to…

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett: It all starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny. DA Bert Cousins turns up, uninvited, with a bottle of gin the grateful guests quickly polish off in their fresh-squeezed orange juice. He also kisses the hostess, sparking a chain of events that will rearrange the Keating and Cousins families in the decades to come. The novel spends time with all six step-siblings, but Franny is definitely the main character – and likely an autobiographical stand-in for Patchett. As a waitress in Chicago, she meets a famous novelist who’s in a slump; the story of her childhood gives him his next bestseller but forces the siblings to revisit a tragic accident they never fully faced up to. Sophisticated and atmospheric; perfect for literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular. Releases September 13th.

by Ann Patchett: It all starts with an early 1960s christening party Los Angeles policeman Fix Keating is throwing for his younger daughter, Franny. DA Bert Cousins turns up, uninvited, with a bottle of gin the grateful guests quickly polish off in their fresh-squeezed orange juice. He also kisses the hostess, sparking a chain of events that will rearrange the Keating and Cousins families in the decades to come. The novel spends time with all six step-siblings, but Franny is definitely the main character – and likely an autobiographical stand-in for Patchett. As a waitress in Chicago, she meets a famous novelist who’s in a slump; the story of her childhood gives him his next bestseller but forces the siblings to revisit a tragic accident they never fully faced up to. Sophisticated and atmospheric; perfect for literary fiction fans in general and Patchett fans in particular. Releases September 13th.

Graphic Novels for Newbies

Following on from last week’s article on quick reads…

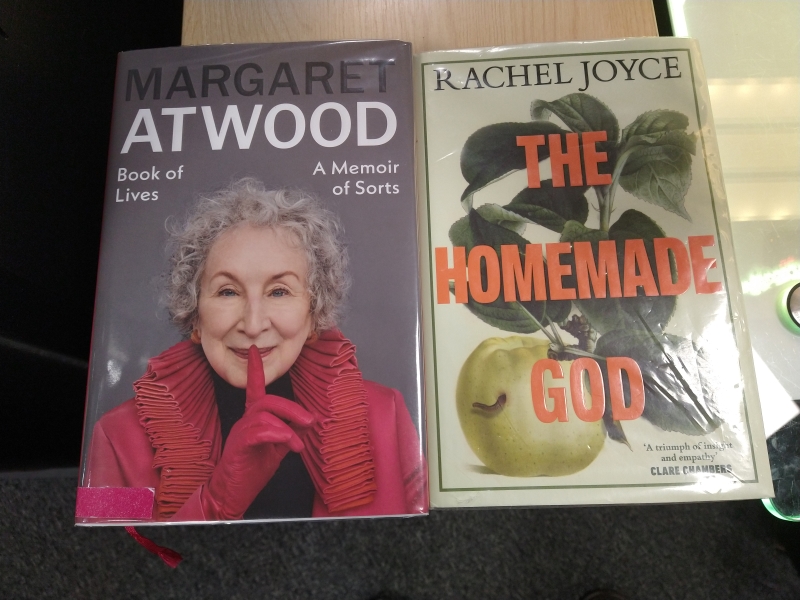

I sometimes wonder if counting graphic novels on my year lists is a bit like cheating, since some are little more than comic books. However, the majority of graphic novels I read have a definite storyline and more words on a page than your average comic. When I worked in London I took advantage of the extensive public library holdings there and tried out a lot of graphic novelists’ work that was new to me. Some of my favorites are Alison Bechdel, Posy Simmonds, Audrey Niffenegger and Joe Sacco. As it happens, I’ve never officially reviewed graphic novels (nor do I own any), but here’s a handful I’ve enjoyed, along with my reading notes:

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

This memoir in graphic novel form is super. Bechdel puts the ‘fun’ in both dysfunctional family and funeral home – the family business her father inherited in small-town Pennsylvania. All through her 1970s upbringing, as Alison grew up coveting men’s shirts and feeling strange quivers of suspicion when she encountered the word “lesbian” in the dictionary, her father was leading a double life, sleeping with the younger men who babysat his kids or helped out with his twin passions of gardening and home renovation.

In an ironic sequence of events, the coming-out letter Alison sent home from college was followed just weeks later by her mother’s revelation of her father’s homosexual indiscretions and their upcoming divorce, and then no more than a few months later by her father’s sudden death. Bruce Bechdel was run down by a Sunbeam Bread truck as he was crossing the road with an armload of cleared brush from a property he was renovating. Was it suicide, or just a horribly arbitrary accident? (The Sunbeam Bread detail sure makes one cringe.) In any case, it was a “mort imbécile,” just as Camus characterized any death by automobile.

Bechdel traces the hints of queerness in her family, the moments when she and her father saw into each other and recognized something familiar. She also muses on the family as a group of frustrated and isolated artists each striving, unfulfilled, towards perfection. This is a thoughtful, powerful memoir, and no less so for being told through a comic strip.

(Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? was also on my BookTrib list of mother–daughter memoirs to read for Mother’s Day.)

This sweet, autobiographical coming-of-age story in graphic novel form is not quite as likable and quick-witted as Fun Home, but it has similar themes such as sexual awakening and the difficulty of understanding one’s parents. Blankets are a linking metaphor: the quilt Craig’s first love, Raina, makes for him; huddling in the same bed with his little brother Phil for warmth during freezing Wisconsin winters; and playing ‘storm at sea’ with the covers.

There’s also an interesting loss-of-faith element to the narrative. Craig is brought up in your average Midwestern fundamentalist Evangelical church and attends youth group, camp, etc. (where he meets Raina); the pastor even wants him to consider going into the ministry, but he doesn’t fit in here – even in the Christian subculture he’s forced into a fringe group of outsiders. Writing and drawing are acts of self-creation and self-preservation. He wants to find a way to use his drawing for good but no one seems to see a value in it. Thus everything, or nothing in particular, leads him to reject his faith when he gets to college.

How satisfying it is to leave a mark on a blank surface. To make a map of my movement – no matter how temporary.

The drawings are lush and bold (though even more so in Thompson’s Habibi). [SPOILERS ahead!] I appreciated how Thompson denies the satisfaction of a happy ending to Craig and Raina’s love story; it’s more realistic this way, recognizing that high school sweethearts rarely stay together. As Raina says, “everything ENDS…everything DEGENERATES, CRUMBLES – so why bother getting started in the first place?” And yet the beauty and power in memory of young love remains, thus Thompson’s rhapsodizing here.

Mrs Weber’s Omnibus by Posy Simmonds

Mrs Weber’s Omnibus by Posy Simmonds

[a collection of her comics for the Guardian]

As with the Garfield cartoons, you get to see the development of Simmonds’s style and the characters, as well as the march of fashion over the period 1977–1993. Very clever skewering of middle class liberal values and political correctness gone mad: the characters (especially polytechnic sociology lecturer George, in the Department of Liberal Studies, and children’s book author Wendy Weber) espouse these values, but their actions don’t always live up to the tolerance they preach. Here are some of the themes:

- 1980s politics: reactionary against Thatcherism; youth unemployment and purposelessness; income inequality; economic and social injustice

- Hypocrisy, avoiding unpleasant truths, compromising youthful ideals

- Middle vs. upper-middle / upper class: second homes, private education

- Place of women: the irony that stay-at-home motherhood is idealized and the difficulties of working motherhood denied (women – liberated to do what?)

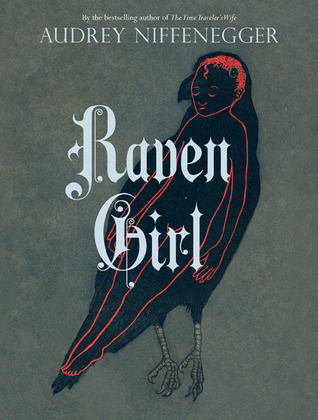

Raven Girl by Audrey Niffenegger

Raven Girl by Audrey Niffenegger

A lovely and simple fairy tale, with classical plot elements like transformation and true love transcending all boundaries. In a quaint English setting, a country postman is tasked with delivering a letter to an address he’s never seen before:

Dripping Rock

Raven’s Nest

2 Flat Drab Manor

East Underwhelm, Otherworld

EE1 LH9 [postcode = East of East, Lower Heights]

Here the postman meets a young raven fallen out of her nest, takes her home to mend her and they fall in love. Even when her wing heals and she can fly, she chooses to stay with him. Their daughter is a mixed creature; she can only croak, but she has no wings and so is raised as a human child. At university she meets a plastic surgeon who can create human-animal chimeras; she begs him to make her wings – a mixture of science and magic. It involves bloody surgery and painful recovery, but in the end she has the wings she’s always felt were hers. Her identity is described in terms very much like Jan Morris’s in Conundrum, when describing her sex change and her knowledge that she was really a girl: “My mother is a raven and my father is a postman, but I feel that truly I should have been a raven.”

Like Niffenegger’s other work, there’s an ever so slightly uncomfortable blend of sinister/grotesque elements with charming, innocuous magic.

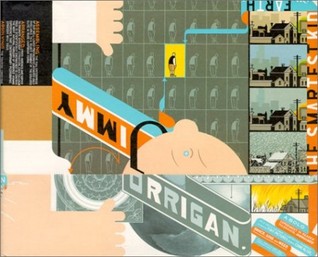

Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware

Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware

This is probably the most peculiar graphic novel I’ve ever read. It’s the story of Jimmy Corrigan, a sad-sack workaholic who, at 36, has no friends apart from his mother, who constantly telephones him. One day he gets a letter from the father he’s never met, asking him to come meet him. And so Jimmy gets on a plane from Chicago out to suburban Michigan. Corrigan is one of those unfortunate-looking fellows who has a potato for a head and a wispy comb-over, and could be anywhere between 30 and 60; he looked little different as a child in the flashback scenes – somewhat like Charlie Brown, also in his depression, diffidence and inability to speak to women.

I much preferred the historical interludes looking at his grandfather (another Jimmy) and his years growing up in Chicago with the World’s Fair under construction. I also liked the more random additions such as patterns for cutting and folding your own model village or business cards with ‘scenic views’ of today’s Waukosha, MI on them.

Parental (verbal) abuse and neglect is a recurring theme, as are bullying from peers, car accidents, and Superman. There’s also an uncomfortable amount of imagined violence – either homicide or suicide.

Also recommended:

Palestine by Joe Sacco

Couch Fiction by Philippa Perry

Days of the Bagnold Summer by Joff Winterhart

Do you read graphic novels? What are some of your favorites?

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

The Boy from the Sea by Garrett Carr: I was entranced by this story of an Irish family in the 1970s–80s: Ambrose, a fisherman left behind by technology; his wife Christine, walked all over by her belligerent father and sister; their son Declan, a budding foodie; and the title character, Brendan, a foundling they adopt and raise. Narrated by a chorus of village voices, this debut has the heart of Claire Keegan and the humour of Paul Murray. It reimagines biblical narratives, too: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau (brotherly rivalry!); Job and more.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,