Tag Archives: Curtis Sittenfeld

The Best Books from the First Half of 2023

Yes, it’s that time of year already! It remains to be seen how many of these will make it onto my overall best-of year list, but for now, these are my 20 highlights. Plus, I sneakily preview another great novel that won’t release until September. (For now I’m highlighting 2023 releases, whereas at the end of the year I divide my best-of lists into current year and backlist. I’ve read 86 current-year releases so far and am working on another 20, so I’m essentially designating a top 20% here.) I give review excerpts and link to the full text from this site or elsewhere. Pictured below are the books I read in print; all the others were e-copies.

Fiction

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman: In 16 sumptuous historical stories, outsiders and pioneers face disability and prejudice with poise. The flash entries crystallize moments of realization, often about health. Longer pieces shine as their out-of-the-ordinary romances have space to develop. In the novella Casting Grand Titans, a botany professor in 1850s Iowa learns her salary is 6% of a male colleague’s. She strives for intellectual freedom, reporting a new-to-science species of moss, while working towards liberation for runaway slaves.

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman: In 16 sumptuous historical stories, outsiders and pioneers face disability and prejudice with poise. The flash entries crystallize moments of realization, often about health. Longer pieces shine as their out-of-the-ordinary romances have space to develop. In the novella Casting Grand Titans, a botany professor in 1850s Iowa learns her salary is 6% of a male colleague’s. She strives for intellectual freedom, reporting a new-to-science species of moss, while working towards liberation for runaway slaves.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland: Moving at a propulsive pace, Beanland’s powerful second novel rotates through the perspectives of these main characters – two men and two women; two white people and two enslaved Black people – caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811 (one of the deadliest events in early U.S. history) and its aftermath. Painstakingly researched and full of historical detail and full-blooded characters, it dramatizes the range of responses to tragedy and how people rebuild their lives.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland: Moving at a propulsive pace, Beanland’s powerful second novel rotates through the perspectives of these main characters – two men and two women; two white people and two enslaved Black people – caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811 (one of the deadliest events in early U.S. history) and its aftermath. Painstakingly researched and full of historical detail and full-blooded characters, it dramatizes the range of responses to tragedy and how people rebuild their lives.

The New Life by Tom Crewe: Two 1890s English sex researchers (based on John Addington Symonds and Havelock Ellis) write a book called Sexual Inversion drawing on ancient Greek history and containing case studies of homosexual behaviour. Oscar Wilde’s trial puts everyone on edge; not long afterwards, their own book becomes the subject of an obscenity trial, and each man has to decide what he’s willing to give up in devotion to his principles. This is deeply, frankly erotic stuff, and, on the sentence level, just exquisite writing.

The New Life by Tom Crewe: Two 1890s English sex researchers (based on John Addington Symonds and Havelock Ellis) write a book called Sexual Inversion drawing on ancient Greek history and containing case studies of homosexual behaviour. Oscar Wilde’s trial puts everyone on edge; not long afterwards, their own book becomes the subject of an obscenity trial, and each man has to decide what he’s willing to give up in devotion to his principles. This is deeply, frankly erotic stuff, and, on the sentence level, just exquisite writing.

Daughters of Nantucket by Julie Gerstenblatt: (Yes, another historical fire novel, and I reviewed both for Shelf Awareness!) This engrossing debut explores the options for women in the mid-19th century. Metaphorical conflagrations blaze in the background in the days leading up to the great Nantucket fire of 1846: each of three female protagonists (a whaling captain’s wife, a museum curator, and a pregnant Black entrepreneur) holds a burning secret and longs for a more expansive, authentic life. Tense and sultry; for Sue Monk Kidd fans.

Daughters of Nantucket by Julie Gerstenblatt: (Yes, another historical fire novel, and I reviewed both for Shelf Awareness!) This engrossing debut explores the options for women in the mid-19th century. Metaphorical conflagrations blaze in the background in the days leading up to the great Nantucket fire of 1846: each of three female protagonists (a whaling captain’s wife, a museum curator, and a pregnant Black entrepreneur) holds a burning secret and longs for a more expansive, authentic life. Tense and sultry; for Sue Monk Kidd fans.

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai: When an invitation comes from her boarding school alma mater, Granby, to teach a two-week course on podcasting, Bodie indulges her obsession with the 1995 murder of her former roommate. Makkai has taken her cues from the true crime genre and constructed a convincing mesh of evidence and theories. She so carefully crafts her pen portraits, and so intimately involves us in Bodie’s psyche, that it’s impossible not to get invested. This is timely, daring, intelligent, enthralling storytelling.

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai: When an invitation comes from her boarding school alma mater, Granby, to teach a two-week course on podcasting, Bodie indulges her obsession with the 1995 murder of her former roommate. Makkai has taken her cues from the true crime genre and constructed a convincing mesh of evidence and theories. She so carefully crafts her pen portraits, and so intimately involves us in Bodie’s psyche, that it’s impossible not to get invested. This is timely, daring, intelligent, enthralling storytelling.

Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain: In this debut collection of 22 short stories, loosely linked by their location in the Appalachian hills in western Pennsylvania and a couple of recurring minor characters, McIlwain softens the harsh realities of addiction, poverty and violence with the tender bruises of infertility and lost love. Grief is a resonant theme in many of the stories, with pregnancy or infant loss a recurring element. At times harrowing, always clear-eyed, these stories are true to life and compassionate about human foibles and animal pain.

Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain: In this debut collection of 22 short stories, loosely linked by their location in the Appalachian hills in western Pennsylvania and a couple of recurring minor characters, McIlwain softens the harsh realities of addiction, poverty and violence with the tender bruises of infertility and lost love. Grief is a resonant theme in many of the stories, with pregnancy or infant loss a recurring element. At times harrowing, always clear-eyed, these stories are true to life and compassionate about human foibles and animal pain.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano: Oprah’s 100th book club pick. It’s a family story spanning three decades and focusing on the Padavanos, a working-class Italian American Chicago clan with four daughters. Julia meets melancholy basketball player William Waters while at Northwestern in the late 1970s. There is such warmth and intensity to the telling, and brave reckoning with bereavement, mental illness, prejudice and trauma. I love sister stories in general, and the subtle echoes of Leaves of Grass and Little Women add heft.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano: Oprah’s 100th book club pick. It’s a family story spanning three decades and focusing on the Padavanos, a working-class Italian American Chicago clan with four daughters. Julia meets melancholy basketball player William Waters while at Northwestern in the late 1970s. There is such warmth and intensity to the telling, and brave reckoning with bereavement, mental illness, prejudice and trauma. I love sister stories in general, and the subtle echoes of Leaves of Grass and Little Women add heft.

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld: Through her work as a writer for a sketch comedy show modelled on Saturday Night Live, Sally Milz meets Noah Brewster, a pop star with surfer-boy good looks. Plain Jane getting the hot guy – that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma… As always, Sittenfeld’s inhabiting of a first-person narrator is flawless, and Sally’s backstory and Covid-lockdown existence endeared her to me. Could this be called predictable? Well, what does one want from a romcom?

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld: Through her work as a writer for a sketch comedy show modelled on Saturday Night Live, Sally Milz meets Noah Brewster, a pop star with surfer-boy good looks. Plain Jane getting the hot guy – that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma… As always, Sittenfeld’s inhabiting of a first-person narrator is flawless, and Sally’s backstory and Covid-lockdown existence endeared her to me. Could this be called predictable? Well, what does one want from a romcom?

In Memoriam by Alice Winn: Heartstopper on the Western Front; swoon! Will Sidney Ellwood and Henry Gaunt both acknowledge that this is love and not just sex, as it is for so many teenage boys at their English boarding school? And will one or both survive the trenches of the First World War? Winn depicts the full horror of war, but in between there is banter, friendship and poetry. Some moments are downright jolly. This debut is obsessively researched, but Winn has a light touch with it. Engaging, thrilling, and, yes, romantic.

In Memoriam by Alice Winn: Heartstopper on the Western Front; swoon! Will Sidney Ellwood and Henry Gaunt both acknowledge that this is love and not just sex, as it is for so many teenage boys at their English boarding school? And will one or both survive the trenches of the First World War? Winn depicts the full horror of war, but in between there is banter, friendship and poetry. Some moments are downright jolly. This debut is obsessively researched, but Winn has a light touch with it. Engaging, thrilling, and, yes, romantic.

A bonus:

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff (Riverhead/Hutchinson Heinemann, 12 September): Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel. (Review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff (Riverhead/Hutchinson Heinemann, 12 September): Groff’s fifth novel combines visceral detail and magisterial sweep as it chronicles a runaway Jamestown servant’s struggle to endure the winter of 1610. Flashbacks to traumatic events seep into her mind as she copes with the harsh reality of life in the wilderness. The style is archaic and postmodern all at once. Evocative and affecting – and as brutal as anything Cormac McCarthy wrote. A potent, timely fable as much as a historical novel. (Review forthcoming for Shelf Awareness.)

Nonfiction

All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett: A lovely memoir about grief and gardening, caring for an ill child and a dying parent. The book is composed of dozens of brief autobiographical, present-tense essays, each titled after a wildflower with traditional healing properties. The format realistically presents bereavement and caring as ongoing, cyclical challenges rather than one-time events. Sitting somewhere between creative nonfiction and nature essays, it’s a beautiful read for any fan of women’s life writing.

All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett: A lovely memoir about grief and gardening, caring for an ill child and a dying parent. The book is composed of dozens of brief autobiographical, present-tense essays, each titled after a wildflower with traditional healing properties. The format realistically presents bereavement and caring as ongoing, cyclical challenges rather than one-time events. Sitting somewhere between creative nonfiction and nature essays, it’s a beautiful read for any fan of women’s life writing.

Monsters by Claire Dederer: The question posed by this hybrid work of memoir and cultural criticism is “Are we still allowed to enjoy the art made by horrible people?” It begins, in the wake of #MeToo, by reassessing the work of film directors Roman Polanski and Woody Allen. The book is as compassionate as it is incisive. While there is plenty of outrage, there is also much nuance. Dederer’s prose is forthright and droll; lucid even when tackling thorny issues. Erudite, empathetic and engaging from start to finish.

Monsters by Claire Dederer: The question posed by this hybrid work of memoir and cultural criticism is “Are we still allowed to enjoy the art made by horrible people?” It begins, in the wake of #MeToo, by reassessing the work of film directors Roman Polanski and Woody Allen. The book is as compassionate as it is incisive. While there is plenty of outrage, there is also much nuance. Dederer’s prose is forthright and droll; lucid even when tackling thorny issues. Erudite, empathetic and engaging from start to finish.

Womb by Leah Hazard: A wide-ranging and accessible study of the uterus, this casts a feminist eye over history and future alike. Blending medical knowledge and cultural commentary, it cannot fail to have both personal and political significance for readers of any gender. The thematic structure of the chapters also functions as a roughly chronological tour of how life with a uterus might proceed: menstruation, conception, pregnancy, labour, caesarean section, ongoing health issues, menopause. Inclusive and respectful of diversity.

Womb by Leah Hazard: A wide-ranging and accessible study of the uterus, this casts a feminist eye over history and future alike. Blending medical knowledge and cultural commentary, it cannot fail to have both personal and political significance for readers of any gender. The thematic structure of the chapters also functions as a roughly chronological tour of how life with a uterus might proceed: menstruation, conception, pregnancy, labour, caesarean section, ongoing health issues, menopause. Inclusive and respectful of diversity.

Sea Bean by Sally Huband: Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects, and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding vibrant beachcombing cultures. In many ways, this is about coming to terms with loss, and the author presents the facts about climate crisis with sombre determination. She writes with such poetic tenderness in this radiant debut memoir.

Sea Bean by Sally Huband: Stories of motherhood, the quest to find effective treatment in a patriarchal medical system, volunteer citizen science projects, and studying Shetland’s history and customs mingle in a fascinating way. Huband travels around the archipelago and further afield, finding vibrant beachcombing cultures. In many ways, this is about coming to terms with loss, and the author presents the facts about climate crisis with sombre determination. She writes with such poetic tenderness in this radiant debut memoir.

Marry Me a Little by Robert Kirby: Hopping around in time, this graphic memoir tells the story of how the author and his partner John decided to get married in 2013. The blue and red color scheme is effective at evoking a polarized America and the ebb and flow of emotions, with blue for calm, happy scenes and concentrated red for confusion or anger. This is political, for sure, but it’s also personal, and it balances those two aims well by tracing the history of gay marriage in the USA and memorializing his own relationship.

Marry Me a Little by Robert Kirby: Hopping around in time, this graphic memoir tells the story of how the author and his partner John decided to get married in 2013. The blue and red color scheme is effective at evoking a polarized America and the ebb and flow of emotions, with blue for calm, happy scenes and concentrated red for confusion or anger. This is political, for sure, but it’s also personal, and it balances those two aims well by tracing the history of gay marriage in the USA and memorializing his own relationship.

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer: In 2019, Vollmer’s mother died of complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Months later, his father reported blinking lights in the woods near the family cemetery. Although Vollmer had left the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in college, his religious upbringing influenced his investigation, which overlapped with COVID-19. Grief, mysticism, and acceptance of the unexplained are resonant themes. An unforgettable record of “a collision with the ineffable.”

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer: In 2019, Vollmer’s mother died of complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Months later, his father reported blinking lights in the woods near the family cemetery. Although Vollmer had left the Seventh-Day Adventist Church in college, his religious upbringing influenced his investigation, which overlapped with COVID-19. Grief, mysticism, and acceptance of the unexplained are resonant themes. An unforgettable record of “a collision with the ineffable.”

Eggs in Purgatory by Genanne Walsh: This autobiographical essay tells the story of the last few months of her father’s life. Aged 89, he lived downstairs from Walsh and her wife in San Francisco. He was quite the character: idealist, stubborn, outspoken; a former Catholic priest. Although he had no terminal conditions, he was sick of old age and its indignities and ready to exit. The task of a memoir is to fully mine the personal details of a situation but make of it something universal, and that’s just what she does here. Stunning.

Eggs in Purgatory by Genanne Walsh: This autobiographical essay tells the story of the last few months of her father’s life. Aged 89, he lived downstairs from Walsh and her wife in San Francisco. He was quite the character: idealist, stubborn, outspoken; a former Catholic priest. Although he had no terminal conditions, he was sick of old age and its indignities and ready to exit. The task of a memoir is to fully mine the personal details of a situation but make of it something universal, and that’s just what she does here. Stunning.

Poetry

More Sky by Joe Carrick-Varty: In this debut collection, the fact of his alcoholic father’s suicide is inescapable. The poet alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it becomes just a sibilant collection of syllables. The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

More Sky by Joe Carrick-Varty: In this debut collection, the fact of his alcoholic father’s suicide is inescapable. The poet alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it becomes just a sibilant collection of syllables. The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

Lo by Melissa Crowe: This incandescent autobiographical collection delves into the reality of sexual abuse and growing up in rural poverty. Guns are insidious, used for hunting or mass shootings. Trauma lingers. “Maybe home is what gets on you and can’t / be shaken loose.” The collection is so carefully balanced in tone that it never feels bleak. In elegies and epithalamiums (poems celebrating marriage), Crowe honors family ties that bring solace. The collection has emotional range: sensuality, fear, and wonder at natural beauty.

Lo by Melissa Crowe: This incandescent autobiographical collection delves into the reality of sexual abuse and growing up in rural poverty. Guns are insidious, used for hunting or mass shootings. Trauma lingers. “Maybe home is what gets on you and can’t / be shaken loose.” The collection is so carefully balanced in tone that it never feels bleak. In elegies and epithalamiums (poems celebrating marriage), Crowe honors family ties that bring solace. The collection has emotional range: sensuality, fear, and wonder at natural beauty.

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of haemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Review forthcoming at The Rumpus.)

Standing in the Forest of Being Alive by Katie Farris: This debut collection addresses the symptoms and side effects of breast cancer treatment at age 36, but often in oblique or cheeky ways – it can be no mistake that “assistance” appears two lines before a mention of haemorrhoids, for instance, even though it closes an epithalamium distinguished by its gentle sibilance (Farris’s husband is Ukrainian American poet Ilya Kaminsky.) She crafts sensual love poems, and exhibits Japanese influences. (Review forthcoming at The Rumpus.)

The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly: Kelly is half-Danish and has single-sided deafness, and her second collection engages with questions of split identity. One section ends with the Deaf community’s outrage that the Prime Minister’s Covid briefings were not translated into BSL. Bizarre but delightful is the sequence of alliteration-rich poems about fungi, followed by a miscellany of autobiographical poems full of references to colour, nature and travel.

The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly: Kelly is half-Danish and has single-sided deafness, and her second collection engages with questions of split identity. One section ends with the Deaf community’s outrage that the Prime Minister’s Covid briefings were not translated into BSL. Bizarre but delightful is the sequence of alliteration-rich poems about fungi, followed by a miscellany of autobiographical poems full of references to colour, nature and travel.

What are some of the best books you’ve read so far this year?

What 2023 releases should I catch up on right away?

April Releases: Frida Kahlo, Games and Rituals, Romantic Comedy

It’s been a big month for new releases and I have loads more April books on the go or waiting in the wings to be reviewed in catch-up posts in the future. For now, I have a biographical graphic novel about a celebrated painter whose medical struggles coloured her art, a set of witty short stories about modern preoccupations and relationships, and a guilty pleasure of a novel from one of my favourite contemporary authors.

Frida Kahlo: Her Life, Her Work, Her Home by Francisco de la Mora

[Translated from the Spanish by Lawrence Schimel]

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on Munch, Van Gogh, Gauguin and O’Keeffe). De la Mora imagines Kahlo (1907–1954) hosting a party at her famous blue house in Coyoacán, Mexico in her final summer – unknown to everyone there, it’s exactly one week before her death. “Hola, come in, welcome. I’m so glad you’re all here. Today is my birthday, and I want to tell all of you the story of my life…” she invites her guests, and thereby the reader. It’s a handy conceit that justifies a chronological approach.

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on Munch, Van Gogh, Gauguin and O’Keeffe). De la Mora imagines Kahlo (1907–1954) hosting a party at her famous blue house in Coyoacán, Mexico in her final summer – unknown to everyone there, it’s exactly one week before her death. “Hola, come in, welcome. I’m so glad you’re all here. Today is my birthday, and I want to tell all of you the story of my life…” she invites her guests, and thereby the reader. It’s a handy conceit that justifies a chronological approach.

I was reminded of traumatic events from Kahlo’s life that I’d already encountered in various places (such as Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson and Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg by Emily Rapp Black): childhood polio and the Mexican Revolution, the hideous bus accident that reshaped her body, and two miscarriages. Periods of confinement alternate with travels. We see her devotion to traditional dress and the development of her frank self-portraiture style. I’d forgotten, or never knew, that she married Diego Rivera twice and divorced in between. They hosted many cultural giants of the time (e.g., Trotsky’s stay with them forms part of Barbara Kingsolver’s The Lacuna), and both had their infidelities. I loved the use of vibrant colours, but learned little. This is really only an introduction for those new to her.

With thanks to Paul Smith and SelfMadeHero for the free copy for review.

Games and Rituals by Katherine Heiny

Early Morning Riser was one of my favourite books of 2021, and I caught up earlier this year with Heiny’s only previous novel, Standard Deviation. Both are hilarious takes on the quirks of relationships, exploring a specific dynamic that recurs in a couple of these stories: the uncomfortable triangle between a man, his second (invariably younger) wife, and the very different, generally formidable, woman he was formerly married to and who continues to play a role in his life. One of the strongest stories is “561,” which was first published as a stand-alone e-book in 2018. Charlie stole Forrest away from Barbara and now the two women have a frosty relationship. It might seem like poetic justice that Charlie later has to load all of Barbara’s possessions into a moving van, but the notion of penance gets murkier when we learn what happened when they worked together on a suicide prevention hotline.

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating.

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating.

Heiny mixes humour with bitter truths in engaging stories about characters whose mistakes and futile attempts to escape the past only make them the more relatable. Her first and last lines are particularly strong; who could resist a piece that opens with “Your elderly father has mistaken his four-thousand-dollar hearing aid for a cashew and eaten it”?

With thanks to 4th Estate for the proof copy for review.

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Curtis Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary authors (I’ve also reviewed You Think It, I’ll Say It and Rodham) and I’ve read everything she’s published. Her work might seem lighter than my usual fare, but I’ve always maintained that she, like Maggie O’Farrell, perfectly treads the line between literary fiction and women’s fiction. This was one of my most anticipated releases of the year and it met my expectations.

Sally Milz is a mid-thirties writer for The Night Owls, a long-running sketch comedy show modelled on Saturday Night Live. Sittenfeld clearly did a lot of research into women in comedy, and Chapter 1 is a convincing blow-by-blow of a typical TNO schedule of pitches, edits, rehearsals, all-nighters and afterparties. This particular week in 2018, the host and musical guest are the same person: Noah Brewster, a pop star with surfer-boy good looks who rose to fame in the early 2000s with radio singles like “Making Love in July” and has maintained steady popularity since then. (I imagined him as a cross between Robbie Williams and Chris Hemsworth.) Sally had been expecting a self-absorbed ignoramus so, when she helps Noah edit a sketch he’s written, is pleasantly surprised to discover he’s actually smart, funny and humble. Sparks seem to fly between them, too, though the week ends all too soon.

Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

The correspondence section was my favourite element. “I do still wonder whether a person’s writing self is their realest self, their fakest self, or just a different self than their in-the-world self?” Sally writes to Noah. As always, Sittenfeld’s inhabiting of a first-person narrator is flawless, and Sally’s backstory and Covid-lockdown, Kansas City existence with her octogenarian stepfather and his beagle endeared her to me. I also appreciated that a woman in her mid- to late thirties could be a romantic lead, and that the question of whether she wants children simply never comes up. Of Sittenfeld’s books, I’d call this closest in tone and content to Eligible, and some familiarity with SNL would probably be of benefit.

Could this be called a predictable story? Well, what does one expect or want from a romcom (watching or reading)? There may be a feminist leaning in places, but this is conventional wish fulfilment, which, I assume, is what keeps romance readers hooked. I enjoyed every sentence and, when it was over, wished I could stay in Sally’s world. (See also Susan’s review.)

With thanks to Doubleday for the proof copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Most Anticipated Releases of 2023

In real life, it can feel like I have little to look forward to. A catch-up holiday gathering and a shortened visit from my sister were over all too soon, and we have yet to book any trips for the summer months. Thankfully, there are always pre-release books to get excited about.

This list of my 20 most anticipated titles covers a bit more than the first half of the year, with the latest publication dates falling in August. I’ve already read 14 releases from 2023 (written up here), and I’m also looking forward to new work from Margaret Atwood, Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, Angie Cruz, Patrick deWitt, Naoise Dolan, Tessa Hadley, Louisa Hall, Leah Hazard, Christian Kiefer, Max Porter, Tom Rachman, Gretchen Rubin, Will Schwalbe, Jenn Shapland, Abraham Verghese, Bryan Washington, Anne Youngson and more, as well as to trying out various debut authors.

The following are in (UK) release date order, within sections by genre. U.S. details given too/instead if USA-only. Quotes are excerpts from the publisher blurbs, e.g., from Goodreads.

Fiction

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download)

The End of Drum-Time by Hanna Pylväinen [Jan. 24, Henry Holt and Co.] I loved Pylväinen’s 2012 debut, We Sinners. This sounds like a winning combination of The Bell in the Lake and The Mercies. “A richly atmospheric saga that charts the repercussions of a scandalous nineteenth century love affair between a young Sámi reindeer herder in the Arctic Circle and the daughter of the renegade Lutheran minister whose teachings are upending the Sámi way of life.” (Edelweiss download)

Heartstopper, Volume 5 by Alice Oseman [Feb. 2, Hodder Children’s] A repeat from my 2022 Most Anticipated post. Will this finally be the year?? I devoured the first four volumes of this teen comic in 2021. Nick will be getting ready to go off to university, so I guess we’ll see how he leaves things with Charlie and whether their relationship will survive a separation. (No cover art yet.)

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy)

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai [Feb. 21, Viking / Feb. 23, Fleet] Makkai has written a couple of stellar novels; this sounds quite different from her usual lit fic but promises Secret History vibes. “A fortysomething podcaster and mother of two, Bodie Kane is content to forget her past [, including] the murder of one of her high school classmates, Thalia Keith. … [But] when she’s invited back to Granby, the elite New England boarding school where she spent four largely miserable years, to teach a course, Bodie finds herself inexorably drawn to the case and its increasingly apparent flaws.” (Proof copy)

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular Goodreads review ever) but fancy trying Catton again – though this sounds like Atwood’s Year of the Flood, redux. “Five years ago, Mira Bunting founded a guerrilla gardening group … Natural disaster has created an opportunity, a sizable farm seemingly abandoned. … Robert Lemoine, the enigmatic American billionaire, has snatched it up to build his end-times bunker. … A gripping psychological thriller … Shakespearean in its wit, drama, and immersion in character.” (NetGalley download)

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton [March 7, Granta / Farrar, Straus and Giroux] I was lukewarm on The Luminaries (my most popular Goodreads review ever) but fancy trying Catton again – though this sounds like Atwood’s Year of the Flood, redux. “Five years ago, Mira Bunting founded a guerrilla gardening group … Natural disaster has created an opportunity, a sizable farm seemingly abandoned. … Robert Lemoine, the enigmatic American billionaire, has snatched it up to build his end-times bunker. … A gripping psychological thriller … Shakespearean in its wit, drama, and immersion in character.” (NetGalley download)

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.”

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 4, Random House / April 6, Doubleday] Sittenfeld is one of my favourite contemporary novelists. “Sally Milz is a sketch writer for The Night Owls, the late-night live comedy show that airs each Saturday. … Enter Noah Brewster, a pop music sensation with a reputation for dating models, who signed on as both host and musical guest for this week’s show. … Sittenfeld explores the neurosis-inducing and heart-fluttering wonder of love, while slyly dissecting the social rituals of romance and gender relations in the modern age.”

The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.”

The Last Animal by Ramona Ausubel [April 18, Riverhead] “Jane is … on the cutting-edge team of a bold project looking to ‘de-extinct’ the woolly mammoth. … As Jane and her daughters ping-pong from the slopes of Siberia to a university in California, from the shores of Iceland to an exotic animal farm in Italy, The Last Animal takes readers on an expansive, bighearted journey that explores the possibility and peril of the human imagination on a changing planet, what it’s like to be a woman and a mother in a field dominated by men, and how a wondrous discovery can best be enjoyed with family. Even teenagers.”

Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my 2021 Most Anticipated post, hopefully here at last! “A story of a couple from two very different restaurant families in rustic Minnesota, and the legacy of love and tragedy, of hardship and hope, that unites and divides them … full of his signature honest, lovable yet fallible Midwestern characters as they grapple with love, loss, and marriage.” (Edelweiss download)

Saturday Night at the Lakeside Supper Club by J. Ryan Stradal [April 18, Pamela Dorman Books] Kitchens of the Great Midwest is one of my all-time favourite debuts. A repeat from my 2021 Most Anticipated post, hopefully here at last! “A story of a couple from two very different restaurant families in rustic Minnesota, and the legacy of love and tragedy, of hardship and hope, that unites and divides them … full of his signature honest, lovable yet fallible Midwestern characters as they grapple with love, loss, and marriage.” (Edelweiss download)

The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download)

The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller [April 20, Fig Tree (Penguin) / June 6, Tin House] Fuller is another of my favourite contemporary novelists and never disappoints. “Neffy is a young woman running away from grief and guilt … When she answers the call to volunteer in a controlled vaccine trial, it offers her a way to pay off her many debts … [and] she is introduced to a pioneering and controversial technology which allows her to revisit memories from her life before.” And apparently there’s also an octopus? (NetGalley download)

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy)

The Late Americans by Brandon Taylor [May 23, Riverhead / June 22, Jonathan Cape (Penguin)] “In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. … These three [main characters] are buffeted by a cast of poets, artists, landlords, meat-packing workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens … [T]he group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.” (Proof copy)

Speak to Me by Paula Cocozza [June 8, Tinder Press] I loved her debut novel, How to Be Human, and this sounds timely. (I have never owned a smartphone.) “When Kurt’s phone rings during sex—and he reaches to pick it up—Susan knows that their marriage has passed the point of no return. … This sense of loss becomes increasingly focused on a cache of handwritten letters, from her first love, Antony, mementoes of a time when devotion seemed to spill out easily onto paper. Increasingly desperate and out of synch with the contemporary world, Susan embarks on a journey of discovery that will reconnect her to her younger self, while simultaneously revealing her future.” (No cover art yet.)

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.”

I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore [June 20, Faber / Knopf] What a title! I’m keen to read more from Moore after her Birds of America got a 5-star rating from me late last year. “Finn is in the grip of middle-age and on an enforced break from work: it might be that he’s too emotional to teach history now. He is living in an America hurtling headlong into hysteria, after all. High up in a New York City hospice, he sits with his beloved brother Max, who is slipping from one world into the next. But when a phone call summons Finn back to a troubled old flame, a strange journey begins, opening a trapdoor in reality.”

A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief.

A Manual for How to Love Us by Erin Slaughter [July 5, Harper Collins] “A debut, interlinked collection of stories exploring the primal nature of women’s grief. … Slaughter shatters the stereotype of the soft-spoken, sorrowful woman in distress, queering the domestic and honoring the feral in all of us. … Seamlessly shifting between the speculative and the blindingly real. … Set across oft-overlooked towns in the American South.” Linked short stories are irresistible for me, and I like the idea of a focus on grief.

Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”.

Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue [Aug. 24, Pan Macmillan / Aug. 29, Little, Brown] Donoghue’s contemporary settings have been a little more successful for me, but she’s still a reliable author whose career I am happy to follow. “Drawing on years of investigation and Anne Lister’s five-million-word secret journal, … the long-buried love story of Eliza Raine, an orphan heiress banished from India to England at age six, and Anne Lister, a brilliant, troublesome tomboy, who meet at the Manor School for young ladies in York in 1805 … Emotionally intense, psychologically compelling, and deeply researched”.

Nonfiction

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.”

The Year of the Cat: A Love Story by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett [Jan. 19, Tinder Press] “When Rhiannon fell in love with, and eventually married her flatmate, she imagined they might one day move on. … The desire for a baby is never far from the surface, but … after a childhood spent caring for her autistic brother, does she really want to devote herself to motherhood? Moving through the seasons over the course of lockdown, [this] nimbly charts the way a kitten called Mackerel walked into Rhiannon’s home and heart, and taught her to face down her fears and appreciate quite how much love she had to offer.”

Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download)

Fieldwork: A Forager’s Memoir by Iliana Regan [Jan. 24, Blackstone] “As Regan explores the ancient landscape of Michigan’s boreal forest, her stories of the land, its creatures, and its dazzling profusion of plant and vegetable life are interspersed with her and Anna’s efforts to make a home and a business of an inn that’s suddenly, as of their first full season there in 2020, empty of guests due to the COVID-19 pandemic. … Along the way she struggles … with her personal and familial legacies of addiction, violence, fear, and obsession—all while she tries to conceive a child that she and her immune-compromised wife hope to raise in their new home.” (Edelweiss download)

Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy)

Enchantment: Reawakening Wonder in an Exhausted Age by Katherine May [Feb. 28, Riverhead / March 9, Faber] I was a fan of her previous book, Wintering. “After years of pandemic life—parenting while working, battling anxiety about things beyond her control, feeling overwhelmed by the news-cycle and increasingly isolated—Katherine May feels bone-tired, on edge and depleted. Could there be another way to live? One that would allow her to feel less fraught and more connected, more rested and at ease, even as seismic changes unfold on the planet? Craving a different path, May begins to explore the restorative properties of the natural world”. (Proof copy)

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer [April 25, Knopf / May 25, Sceptre] “What do we do with the art of monstrous men? Can we love the work of Roman Polanski and Michael Jackson, Hemingway and Picasso? Should we love it? Does genius deserve special dispensation? Is history an excuse? What makes women artists monstrous? And what should we do with beauty, and with our unruly feelings about it? Dederer explores these questions and our relationships with the artists whose behaviour disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms. She interrogates her own responses and her own behaviour, and she pushes the fan, and the reader, to do the same.”

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer [April 25, Knopf / May 25, Sceptre] “What do we do with the art of monstrous men? Can we love the work of Roman Polanski and Michael Jackson, Hemingway and Picasso? Should we love it? Does genius deserve special dispensation? Is history an excuse? What makes women artists monstrous? And what should we do with beauty, and with our unruly feelings about it? Dederer explores these questions and our relationships with the artists whose behaviour disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms. She interrogates her own responses and her own behaviour, and she pushes the fan, and the reader, to do the same.”

Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

Undercurrent: A Cornish Memoir of Poverty, Nature and Resilience by Natasha Carthew [May 25, Hodder Studio] Carthew hangs around the fringes of UK nature writing, mostly considering the plight of the working class. “Carthew grew up in rural poverty in Cornwall, battling limited opportunities, precarious resources, escalating property prices, isolation and a community marked by the ravages of inequality. Her world existed alongside the postcard picture Cornwall … part-memoir, part-investigation, part love-letter to Cornwall. … This is a journey through place, and a story of hope, beauty, and fierce resilience.”

Grief Is for People by Sloane Crosley [June 25, MCD Books] According to Crosley, this is “a five-part book about many kinds of loss.” The press release adds to that: “Telling the interwoven story of a burglary, the suicide of Crosley’s closest friend, and the onset of Covid in New York City, [this] is the first full-length work of nonfiction by a writer best known for her acclaimed, bestselling books of essays.” (No cover art yet.)

Poetry

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan [Aug. 23, Faber] Their debut collection, Flèche, was my top poetry release in 2019. “These piercing poems fearlessly explore intertwined themes of queer identity, multilingualism and postcolonial legacy: interrogating acts of Covid racism, instances of queerphobia and the hegemony of the English language. Questions of acceptance and assimilation are further explored through a family’s evolving dynamics over time, or through the specious jargon of ‘Equality, Diversity and Inclusion’.” (No cover art yet.)

Other lists for more ideas:

What catches your eye here? What other 2023 titles do I need to know about?

Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau (Blog Tour)

Are you having a groovy June yet? If not, I have just the remedy: a juicy coming-of-age novel that drops you directly into the Baltimore summer of 1975. Mary Jane Dillard, 14, lives in the upper-class white neighborhood of Roland Park. Her parents are prim types who attend church every week, belong to a country club, and pray for the (Republican) president’s health before each sit-down family dinner. When Mary Jane starts working as a daytime nanny for five-year-old Izzy, the Cones’ way of life is a revelation to her. They are messy bohemians who think nothing of walking around the house half-naked, shouting up and down the stairs at each other, or leaving a fridge full of groceries to rot and going out for fast food instead.

Dr. Cone is a psychiatrist whose top-secret assignment is helping a rock star to kick his drug addiction. Jimmy and his actress wife, Sheba, move into the Cones’ attic for the summer. If they go out in public, they wear wigs and pretend to be friends visiting from Rhode Island. While the Cones are busy monitoring or trying to imitate their celebrity guests, Mary Jane introduces discipline by cleaning the kitchen, alphabetizing the bookcase, and replicating her mother’s careful weekly menus with food she buys from Eddie’s market. In some ways she seems the most responsible member of the household, but in others she’s painfully naïve, entirely ignorant of sex and unaware that her name is a slang term for marijuana.

Dr. Cone is a psychiatrist whose top-secret assignment is helping a rock star to kick his drug addiction. Jimmy and his actress wife, Sheba, move into the Cones’ attic for the summer. If they go out in public, they wear wigs and pretend to be friends visiting from Rhode Island. While the Cones are busy monitoring or trying to imitate their celebrity guests, Mary Jane introduces discipline by cleaning the kitchen, alphabetizing the bookcase, and replicating her mother’s careful weekly menus with food she buys from Eddie’s market. In some ways she seems the most responsible member of the household, but in others she’s painfully naïve, entirely ignorant of sex and unaware that her name is a slang term for marijuana.

Open marriage, sex addiction and group therapy are new concepts that soon become routine for our confiding narrator, as she adopts a ‘What they don’t know can’t hurt them’ stance towards her trusting parents. Blau is the author of four previous YA novels, and while this is geared towards adults, it resonates for how it captures the uncertainty and swirling hormones of the teenage years. Who didn’t share Mary Jane’s desperate curiosity to learn about sex? Who can’t remember a moment of realization that parents aren’t right about everything?

Music runs all through the book, creating and cementing bonds between the characters. Mary Jane sings in the choir and shares her mother’s love of both church music and show tunes. Jimmy and Sheba are always making up little songs on which Mary Jane harmonizes, and a clandestine trip to a record store in an African American part of town forms one of the novel’s pivotal scenes. The relationship between Mary Jane and Izzy, who is precocious and always coming out with malapropisms, is touching, and Blau cleverly inserts references to the casual racism and antisemitism of the 1970s.

I love it when a novel has a limited setting and can evoke a sense of wistfulness for a golden time that will never come again. I highly recommend this for nostalgic summer reading, particularly if you’ve enjoyed work by Curtis Sittenfeld – especially Prep and Rodham.

My thanks to Harper360 UK and Anne Cater for arranging my proof copy for review.

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for Mary Jane. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Review Book Catch-Up: Ante, Evans, Foster and White

Today I have a book of poems about the Filipinx experience in the UK, a collection of short stories reflecting on racial injustice, a monograph on a bird that spells summer for many of us, and a biographical investigation into a little-understood medical condition.

Antiemetic for Homesickness by Romalyn Ante

I was drawn to this debut collection by the terrific title and cover, but also by the accolades it received: it was on the Dylan Thomas Prize longlist and the Jhalak Prize shortlist. I hope we’ll see it on the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist, too. Ante grew up in the Philippines but at age 16 joined her mother in the UK, where she had moved years before to work as a nurse in the NHS. She has since followed in her mother’s footsteps as a nurse – indeed, overseas Filipinx workers (Jamaicans, too) are a mainstay of the NHS.

Ante remembers the years when her mother was absent but promised to send for the rest of the family soon: “You said all I needed to do was to sleep and before I knew it, / you’d be back. But I woke to the rice that needed rinsing, / my siblings’ school uniforms that needed ironing.” The medical profession as a family legacy and noble calling is a strong element of these poems, especially in “Invisible Women,” an ode to the “goddesses of caring and tending” who walk the halls of any hospital. Hard work is a matter of survival, and family – whether physically present or not – bolsters weary souls. A series of short, untitled poems are presented as tape recordings made for her mother.

Ante remembers the years when her mother was absent but promised to send for the rest of the family soon: “You said all I needed to do was to sleep and before I knew it, / you’d be back. But I woke to the rice that needed rinsing, / my siblings’ school uniforms that needed ironing.” The medical profession as a family legacy and noble calling is a strong element of these poems, especially in “Invisible Women,” an ode to the “goddesses of caring and tending” who walk the halls of any hospital. Hard work is a matter of survival, and family – whether physically present or not – bolsters weary souls. A series of short, untitled poems are presented as tape recordings made for her mother.

Food is inextricably entwined with memory (reminding me of Nina Mingya Powles’s approach in Tiny Moons) and provides some of the standout metaphors, especially in “Patis” and “Ode to a Pot Noodle.” Ante uses a lot of alliteration and adapts various forms. I especially liked “Tagay!”, a traditional drinking song, and “Mateo,” printed in the shape of a pound sign. The nuanced look at the immigrant experience reminded me of Jenny Xie’s Eye Level. Movement entails losses as well as benefits. The focus on the Filipinx experience also made me think of America Is Not the Heart. My favourite single poem was “The Making of a Smuggler,” which opens “Wherever we travel, we carry / the whole country with us – // our rice terraces are folded garments, / we have pillars of trees, a rainforest // on a hairbrush.”

Favourite lines:

“Gone are the nights he steals / the moon with a mango picker / and swaps it for her pocket mirror”

“The yellow admission papers in my hands escaped / flustering at my face into a flight of orioles.”

“I am halved in order to be whole – / I rebuild by leaving / everything I love.”

With thanks to Chatto & Windus for the free copy for review.

The Office of Historical Corrections by Danielle Evans

To boil these six stories and a novella down to the topic of race in America risks painting them as solemn or strident – more concerned with meaning than with art – when the truth is that they are playful and propulsive even though they keep cycling back to bereavement and injustice. Several of the protagonists are young Black women coming to terms with a loss.

In “Happily Ever After,” Lyssa works in the gift shop of a Titanic replica and is cast as an extra in a pop star’s music video. Mythical sea monsters are contrasted with the real dangers of her life, like cancer and racism. “Anything Could Disappear” was a favourite of mine, though it begins with that unlikely scenario of a single woman acquiring a baby as if by magic. What starts off as a burden becomes a bond she can’t bear to let go. A family is determined to clear the name of their falsely imprisoned ancestor in “Alcatraz.” In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” (a mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow), photojournalist Rena is wary about attending the wedding of a friend she met when their plane was detained in Africa some years ago. The only wedding she’s been in is her sister’s, which ended badly.

In “Happily Ever After,” Lyssa works in the gift shop of a Titanic replica and is cast as an extra in a pop star’s music video. Mythical sea monsters are contrasted with the real dangers of her life, like cancer and racism. “Anything Could Disappear” was a favourite of mine, though it begins with that unlikely scenario of a single woman acquiring a baby as if by magic. What starts off as a burden becomes a bond she can’t bear to let go. A family is determined to clear the name of their falsely imprisoned ancestor in “Alcatraz.” In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” (a mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow), photojournalist Rena is wary about attending the wedding of a friend she met when their plane was detained in Africa some years ago. The only wedding she’s been in is her sister’s, which ended badly.

Mistakes and deceit seem to follow these characters. In the title novella that closes the book, Cassie and her colleagues combat fake news, going around putting correction labels on plaques that whitewash history. When she and her former colleague meet up in Wisconsin to find the truth behind a complex correction case, a clash with a white supremacist group quickly turns pedantry into a matter of life and death. The story I’d heard the most about beforehand was “Boys Go to Jupiter,” about a college girl who dons a Confederate flag bikini, not caring what message it sends to others in her dorm. It turns out she has history with a Black family, but has chosen to airbrush this experience out of her life.

There was only one story I didn’t care for, “Why Won’t Women Just Say What They Want,” about a celebrity who turns apologizing into performance art. Overall, this is a very strong collection I would recommend to readers of Brit Bennett and Raven Leilani, with some stories also reminding me of recent work by Curtis Sittenfeld and Mary South. I’ll be sure to seek out Evans’s previous book (also short stories), too.

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

The Screaming Sky by Charles Foster

The other week I was volunteering at our local community garden and looked up to see a dozen common swifts wheeling over the Kennet & Avon canal and picking off insects among the treetops. I hope this fellow Foster (for whom my husband was once confused on a nature conference attendee list) would be proud of me for pausing to gaze at the birds for a while. My impression of the author is as a misanthropic eccentric. A Renaissance man as well versed in law and theology as he is in natural history, he’s obsessed with swifts and ashamed of his own species: for looking down at their feet when they could be watching the skies; for the “pathological tidiness” that leaves swifts and so many other creatures no place to live.

The obsession began when he was eight years old and someone brought him a dead swift fledgling for his taxidermy hobby. Ever since, he’s dated the summer by their arrival. “It is always summer for them,” though, as his opening line has it. This monograph is structured chronologically. Much like Tim Dee does in Greenery, Foster follows the birds for a year: from their winter territory in Africa to the edges of Europe in spring and then to his very own Oxford street in high summer. When they leave, he’s bereft and ready to book a flight back to Africa.

The obsession began when he was eight years old and someone brought him a dead swift fledgling for his taxidermy hobby. Ever since, he’s dated the summer by their arrival. “It is always summer for them,” though, as his opening line has it. This monograph is structured chronologically. Much like Tim Dee does in Greenery, Foster follows the birds for a year: from their winter territory in Africa to the edges of Europe in spring and then to his very own Oxford street in high summer. When they leave, he’s bereft and ready to book a flight back to Africa.

Along the way, Foster delivers heaps of information: the fossil evidence of swifts, how they know where to migrate (we have various theories but don’t really know), their nesting habits and lifespan, and the typical fates of those individuals that don’t survive. But, thumbing his nose at his “ex-friend” (a closed-minded biologist he repeatedly, and delightfully, rails against), he refuses to stick to a just-the-facts approach. Acknowledging the risks of anthropomorphizing, he speaks of swifts as symbols of aspiration, of life lived with intensity. He believes that we can understand animal emotions analogously through our own, so that, inappropriate as such words might seem, we can talk about what birds hope and plan for. He scorns reductive ecosystem services lingo that defines creatures by what we get out of them.

Also like Dee, Foster quotes frequently from poetry. His prose is full of sharp turns of phrase and moments of whimsy and made me eager to try more of his work (I know the most about but have not yet read Being a Beast).

Swifts know the roar of lions better than the roar of the M25, the piping of hornbills better than the Nunc Dimittis of parish Evensong … Are memories of our eaves spiralling high above the Gulf of Guinea? … They don’t seem to prevaricate. One moment they’re there, the next they’re off, diving straight into the journey. It’s the way we should run into cold water.

As I’ve found with a number of Little Toller releases now (On Silbury Hill, Snow, Landfill), knowledge meets passion to create a book that could make an aficionado of the most casual of readers. Towards the close I was also reminded of Richard Smyth’s An Indifference of Birds: “When Homo sapiens has gone there will be lots of ideal swift holes in the decaying buildings we’ll leave behind.” It’s comforting to think of natural cycles continuing after we’re gone … but let’s start making the space for them now. Jonathan Pomroy’s black-and-white illustrations of swift behaviour only add to this short book’s charms.

As I’ve found with a number of Little Toller releases now (On Silbury Hill, Snow, Landfill), knowledge meets passion to create a book that could make an aficionado of the most casual of readers. Towards the close I was also reminded of Richard Smyth’s An Indifference of Birds: “When Homo sapiens has gone there will be lots of ideal swift holes in the decaying buildings we’ll leave behind.” It’s comforting to think of natural cycles continuing after we’re gone … but let’s start making the space for them now. Jonathan Pomroy’s black-and-white illustrations of swift behaviour only add to this short book’s charms.

With thanks to Little Toller Books for the free copy for review.

Waiting for Superman: One Family’s Struggle to Survive – and Cure – Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Tracie White

Like Suzanne O’Sullivan’s books (most recently, The Sleeping Beauties), this is presented as an investigation into a medical mystery. White, a Stanford Medicine journalist, focuses on one family that has been indelibly changed by chronic fatigue syndrome – now linked with myalgic encephalomyelitis and termed ME/CFS for short. Whitney Dafoe was a world traveller and promising photographer before, in 2010, a diagnosis of ME/CFS explained his exhaustion and gastrointestinal problems. By the time White first met the family in 2016, the thirtysomething was bedbound in his parents’ home with a feeding tube, only able to communicate via gestures and rearranging Scrabble tiles. He couldn’t bear loud noises, or to be touched. At times he was nearly comatose.

Whitney’s father, Ron Davis, is a Stanford geneticist whose research has contributed to the Human Genome Project. He has devoted himself to studying ME/CFS, which affects 20 million people worldwide yet receives little research funding; he calls it “the last major disease we know nothing about.” Testing his son’s blood, he found a problem with the citric acid cycle that produces ATP, essential fuel for the body’s cells – proof that there was a physiological reason for Whitney’s condition. Frustratingly, though, a Stanford colleague who examined Whitney prescribed a psychological intervention. This is in line with the current standard of care for ME/CFS: a graded exercise regime (nigh on impossible for someone who can’t get out of bed) and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Whitney’s father, Ron Davis, is a Stanford geneticist whose research has contributed to the Human Genome Project. He has devoted himself to studying ME/CFS, which affects 20 million people worldwide yet receives little research funding; he calls it “the last major disease we know nothing about.” Testing his son’s blood, he found a problem with the citric acid cycle that produces ATP, essential fuel for the body’s cells – proof that there was a physiological reason for Whitney’s condition. Frustratingly, though, a Stanford colleague who examined Whitney prescribed a psychological intervention. This is in line with the current standard of care for ME/CFS: a graded exercise regime (nigh on impossible for someone who can’t get out of bed) and cognitive behavioural therapy.

White delves into Whitney’s past, looking for clues to what could have triggered his illness (having mono in high school? a parasite he picked up in India?). She also goes back to the mid-1980s to consider the Lake Tahoe outbreak of ME/CFS, whose victims “looked too healthy to be sick and were repeatedly disbelieved.” The media called it “yuppie flu,” downplaying the extreme fatigue involved. White also meets Laura Hillenbrand, author of Seabiscuit, who suffers from ME/CFS and managed to write her bestselling books from bed. Like Whitney, she only has a certain allotment of energy and mustn’t use it up too fast.

- A neat connection: Stephanie Land, author of Maid, was Whitney’s ex-girlfriend when he was 19 and living in Alaska; she wrote a Longreads article about their relationship.

- The title is from a Flaming Lips lyric and expresses Whitney’s trust in his dad’s ability to cure him; the U.S. title is The Puzzle Solver and the working title was The Invisible Patient.

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

20 Books of Summer 2021 (Colour Theme) & Other Reading Plans

It’s my fourth year participating in Cathy’s 20 Books of Summer challenge. Three years ago, I read only books by women; two years ago, I did an animal theme; last year, all my choices were related to food and drink. This year it’s all about colour: the word colour, or one mentioned in a title or in an author’s name, or – if I get really stuck – a particularly vibrant one on a book cover. My options range from short stories to biography, with a couple of novels in translation and a couple of children’s classics to reread on the piles.

As usual, I will prioritize books from my own shelves, but this time I will also allow myself to include library and/or Kindle reads. For instance, I have a hold placed on Nothing but Blue Sky by Kathleen MacMahon, which was on the Women’s Prize longlist.

Here are the initial stacks I’m choosing from:

One that’s not pictured but that I definitely plan to read and review over the summer is God Is Not a White Man by Chine McDonald, which came out earlier this month.

One that’s not pictured but that I definitely plan to read and review over the summer is God Is Not a White Man by Chine McDonald, which came out earlier this month.

Tomorrow I’m flying out to the USA as my mother is getting remarried in mid-June. I’m not completely at ease about travelling, especially as on this occasion it has involved expensive private Covid testing and quarantine periods at either end, but I am looking forward to the fun aspects of travel, like downtime in an airport with nothing to do but read. For this purpose, the first two books for my challenge that I’ve packed are the novel Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and the short story collection Emerald City by Jennifer Egan.

This week and next, the Hay Festival is taking place. I went nuts and booked myself onto eight different literary talks, three of which have already aired, with two more coming up this evening. Then there will be a few to keep me occupied during my first few days of quarantine next week. It’s a fantastic program and all the online events are free (though you can donate), so do take a look if you haven’t already. I’ll try to write up at least some of these events.

Liz’s Anne Tyler readalong is continuing throughout this year, and I happen to own one novel that’s scheduled for each of the next three months: Saint Maybe for June, A Patchwork Planet for July, and An Amateur Marriage for August. The last two I’ll be rescuing from boxes in my sister’s basement.

I always like reading with the seasons, so this is my summery stack:

I’ll start with Three Junes. Others I will contemplate getting out from the library include Heatstroke by Hazel Barkworth, The Summer before the Dark by Doris Lessing, and August by Callan Wink.

In mid-June I’m on the blog tour for Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau, a novel that’s perfect for the season’s reading – nostalgic for a teen girl’s music-drenched 1970s summer, and reminiscent of Curtis Sittenfeld’s work.

In mid-June I’m on the blog tour for Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau, a novel that’s perfect for the season’s reading – nostalgic for a teen girl’s music-drenched 1970s summer, and reminiscent of Curtis Sittenfeld’s work.

I have also managed to amass a bunch of books about fathers and fatherhood, so I’ll do at least one “Three on a Theme” post to tie in with Father’s Day.

Are you joining in the summer reading challenge? What’s the first book on the docket?

Do you spy any favourites on my piles? Which ones should I be sure to read?

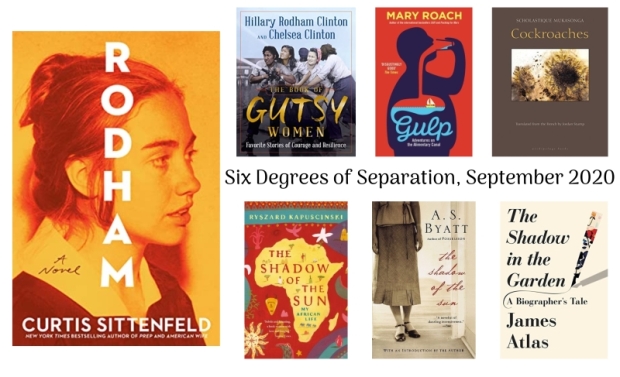

Six Degrees of Separation: From Shuggie Bain to Girl, Woman, Other

This month we begin with Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart (2020), last year’s Booker Prize winner. (See Kate’s opening post.) I tried it a couple of times and couldn’t get past page 100, but I’ve kept my proof copy on the shelf to try some other time.

#1 The main character’s sweet nickname takes me to Sugar and Other Stories by A.S. Byatt. Byatt is my favourite author. Rereading her The Matisse Stories last year was rewarding, and I’d eventually like to go back to the rest of her short fiction. I read Sugar and Other Stories in Bath in 2006. (As my MA year in Leeds came to a close, I interviewed at several libraries, hoping to get onto a graduate trainee scheme so I could stay in the UK for another year. It didn’t work out, but I got to tour many wonderful libraries.) I picnicked on the grass on a May day on the University of Bath campus before my interview at the library.