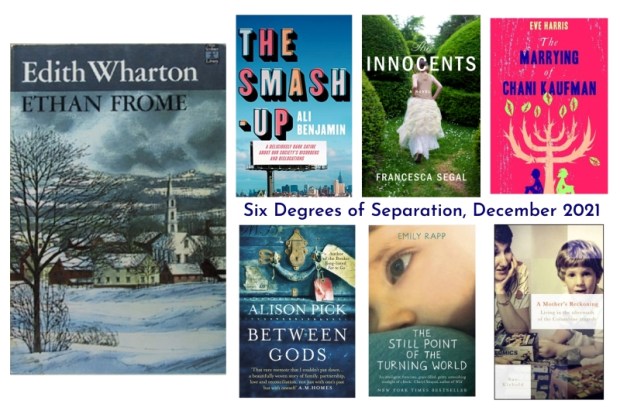

Six Degrees: Ethan Frome to A Mother’s Reckoning

This month we began with Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton, which was our buddy read for the short classics week of Novellas in November. I reread and reviewed it recently. (See Kate’s opening post.)

#1 When I posted an excerpt of my Ethan Frome review on Instagram, I got a comment from the publicist who was involved with the recent UK release of The Smash-Up by Ali Benjamin, a modern update of Wharton’s plot. Here’s part of the blurb: “Life for Ethan and Zo used to be simple. Ethan co-founded a lucrative media start-up, and Zo was well on her way to becoming a successful filmmaker. Then they moved to a rural community for a little more tranquility—or so they thought. … Enter a houseguest who is young, fun, and not at all concerned with the real world, and Ethan is abruptly forced to question everything: his past, his future, his marriage, and what he values most.” I’m going to try to get hold of a review copy when the paperback comes out in February.

#1 When I posted an excerpt of my Ethan Frome review on Instagram, I got a comment from the publicist who was involved with the recent UK release of The Smash-Up by Ali Benjamin, a modern update of Wharton’s plot. Here’s part of the blurb: “Life for Ethan and Zo used to be simple. Ethan co-founded a lucrative media start-up, and Zo was well on her way to becoming a successful filmmaker. Then they moved to a rural community for a little more tranquility—or so they thought. … Enter a houseguest who is young, fun, and not at all concerned with the real world, and Ethan is abruptly forced to question everything: his past, his future, his marriage, and what he values most.” I’m going to try to get hold of a review copy when the paperback comes out in February.

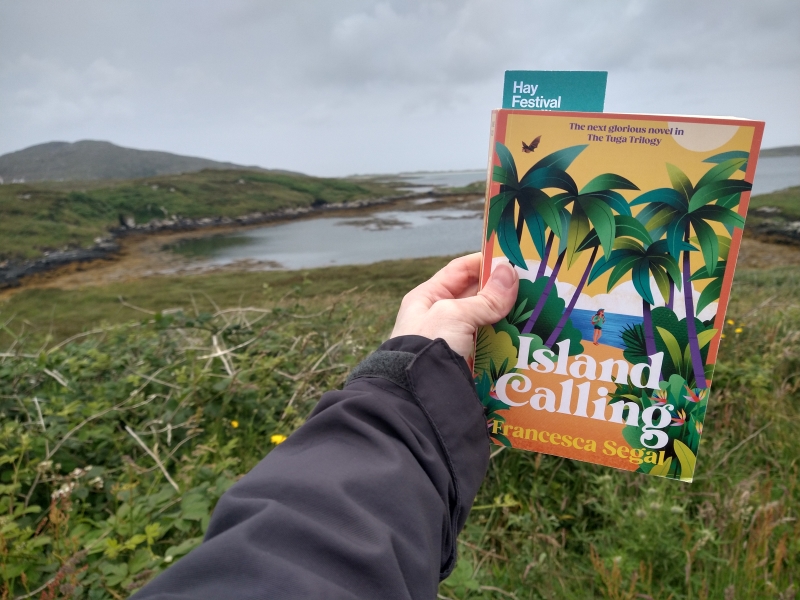

#2 One of my all-time favourite debut novels is The Innocents by Francesca Segal, which won the Costa First Novel Award in 2012. It is also a contemporary reworking of an Edith Wharton novel, this time The Age of Innocence. Segal’s love triangle, set in a world I know very little about (the tight-knit Jewish community of northwest London), stays true to the emotional content of the original: the interplay of love and desire, jealousy and frustration. Adam Newman has been happily paired with Rachel Gilbert for nearly 12 years. Now engaged, Adam and Rachel seem set to become pillars of the community. Suddenly, their future is threatened by the return of Rachel’s bad-girl American cousin, Ellie Schneider.

#2 One of my all-time favourite debut novels is The Innocents by Francesca Segal, which won the Costa First Novel Award in 2012. It is also a contemporary reworking of an Edith Wharton novel, this time The Age of Innocence. Segal’s love triangle, set in a world I know very little about (the tight-knit Jewish community of northwest London), stays true to the emotional content of the original: the interplay of love and desire, jealousy and frustration. Adam Newman has been happily paired with Rachel Gilbert for nearly 12 years. Now engaged, Adam and Rachel seem set to become pillars of the community. Suddenly, their future is threatened by the return of Rachel’s bad-girl American cousin, Ellie Schneider.

#3 Also set in north London’s Jewish community is The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Chani is the fifth of eight daughters in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Golders Green. The story begins and closes with Chani and Baruch’s wedding ceremony, and in between it loops back to detail their six-month courtship and highlight a few events from their family past. It’s a light-hearted, gossipy tale of interclass matchmaking in the Jane Austen vein.

#3 Also set in north London’s Jewish community is The Marrying of Chani Kaufman by Eve Harris, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2013. Chani is the fifth of eight daughters in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family in Golders Green. The story begins and closes with Chani and Baruch’s wedding ceremony, and in between it loops back to detail their six-month courtship and highlight a few events from their family past. It’s a light-hearted, gossipy tale of interclass matchmaking in the Jane Austen vein.

#4 I learned more about Jewish beliefs and rituals via several memoirs, including Between Gods by Alison Pick. Her paternal grandparents escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Holocaust; she only found out that her father was Jewish through eavesdropping. In 2008 the author (a Toronto-based novelist and poet) decided to convert to Judaism. The book vividly depicts a time of tremendous change, covering a lot of other issues Pick was dealing with simultaneously, such as depression, preparation for marriage, pregnancy, and so on.

#4 I learned more about Jewish beliefs and rituals via several memoirs, including Between Gods by Alison Pick. Her paternal grandparents escaped Czechoslovakia just before the Holocaust; she only found out that her father was Jewish through eavesdropping. In 2008 the author (a Toronto-based novelist and poet) decided to convert to Judaism. The book vividly depicts a time of tremendous change, covering a lot of other issues Pick was dealing with simultaneously, such as depression, preparation for marriage, pregnancy, and so on.

#5 One small element of Pick’s story was her decision to be tested for the BRCA gene because it’s common among Ashkenazi Jews. Tay-Sachs disease is usually found among Ashkenazi Jews, but because only her husband was Jewish, Emily Rapp never thought to be tested before she became pregnant with her son Ronan. Had she known she was also a carrier, things might have gone differently. The Still Point of the Turning World was written while her young son was still alive, but terminally ill.

#5 One small element of Pick’s story was her decision to be tested for the BRCA gene because it’s common among Ashkenazi Jews. Tay-Sachs disease is usually found among Ashkenazi Jews, but because only her husband was Jewish, Emily Rapp never thought to be tested before she became pregnant with her son Ronan. Had she known she was also a carrier, things might have gone differently. The Still Point of the Turning World was written while her young son was still alive, but terminally ill.

#6 Another wrenching memoir of losing a son: A Mother’s Reckoning by Sue Klebold, whose son Dylan was one of the Columbine school shooters. I was in high school myself at the time, and the event made a deep impression on me. Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is Klebold’s determination to reclaim Columbine as a murder–suicide and encourage mental health awareness; all author proceeds were donated to suicide prevention and mental health charities. There’s no real redemptive arc, though, no easy answers; just regrets. If something similar could happen to any family, no one is immune. And Columbine was only one of many major shootings. I finished this feeling spent, even desolate. Yet this is a vital book everyone should read.

#6 Another wrenching memoir of losing a son: A Mother’s Reckoning by Sue Klebold, whose son Dylan was one of the Columbine school shooters. I was in high school myself at the time, and the event made a deep impression on me. Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is Klebold’s determination to reclaim Columbine as a murder–suicide and encourage mental health awareness; all author proceeds were donated to suicide prevention and mental health charities. There’s no real redemptive arc, though, no easy answers; just regrets. If something similar could happen to any family, no one is immune. And Columbine was only one of many major shootings. I finished this feeling spent, even desolate. Yet this is a vital book everyone should read.

So, I’ve gone from one unremittingly bleak book to another, via sex, religion and death. Nothing for cheerful holiday reading – or a polite dinner party conversation – here! All my selections were by women this month.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Next month’s starting point is Rules of Civility by Amor Towles; I have a copy on the shelf and this would be a good excuse to read it!

Have you read any of my selections? Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Three on a Theme: Queer Family-Making

Several 2021 memoirs have given me a deeper understanding of the special challenges involved when queer couples decide they want to have children.

“It’s a fundamentally queer principle to build a family out of the pieces you have”

~Jennifer Berney

“That’s the thing[:] there are no accidental children born to homosexuals – these babies are always planned for, and always wanted.”

~Michael Johnson-Ellis

The Other Mothers by Jennifer Berney

Berney remembers hearing the term “test-tube baby” for the first time in a fifth-grade sex ed class taught by a lesbian teacher at her Quaker school. By that time she already had an inkling of her sexuality, so suspected that she might one day require fertility help herself.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

By the time she met her partner, Kellie, she knew she wanted to be a mother; Kellie was unsure. Once they were finally on the same page, it wasn’t an easy road to motherhood. They purchased donated sperm through a fertility clinic and tried IUI, but multiple expensive attempts failed. Signs of endometriosis had doctors ready to perform invasive surgery, but in the meantime the couple had met a friend of a friend (Daniel, whose partner was Rebecca) who was prepared to be their donor. Their at-home inseminations resulted in a pregnancy – after two years of trying to conceive – and, ultimately, in their son. Three years later, they did the whole thing all over again. Rebecca had sons at roughly the same time, too, giving their boys the equivalent of same-age cousins – a lovely, unconventional extended family.

It surprised me that the infertility business seemed entirely set up for heterosexual couples – so much so that a doctor diagnosed the problem, completely seriously, in Berney’s chart as “Male Factor Infertility.” This was in Washington state in c. 2008, before the countrywide legalization of gay marriage, so it’s possible the situation would be different now, or that the couple would have had a different experience had they been based somewhere like San Francisco where there is a wide support network and many gay-friendly resources.

Berney finds the joy and absurdity in their journey as well as the many setbacks. I warmed to the book as it went along: early on, it dragged a bit as she surveyed her younger years and traced the history of IVF and alternatives like international adoption. As the storyline drew closer to the present day, there was more detail and tenderness and I was more engaged. I’d read more from this author. (Published by Sourcebooks. Read via NetGalley)

small: on motherhoods by Claire Lynch

A line from Berney’s memoir makes a good transition into this one: “I felt a sense of dread: if I turned out to be gay I believed my life would become unbearably small.” The word “small” is a sort of totem here, a reminder of the microscopic processes and everyday miracles that go into making babies, as well as of the vulnerability of newborns – and of hope.

Lynch and her partner Beth’s experience in England was reminiscent of Berney’s in many ways, but with a key difference: through IVF, Lynch’s eggs were added to donor sperm to make the embryos implanted in Beth’s uterus. Mummy would have the genetic link, Mama the physical tie of carrying and birthing. It took more than three years of infertility treatment before they conceived their twin girls, born premature; they were followed by another daughter, creating a crazy but delightful female quintet. The account of the time when their daughters were in incubators reminded me of Francesca Segal’s Mother Ship.

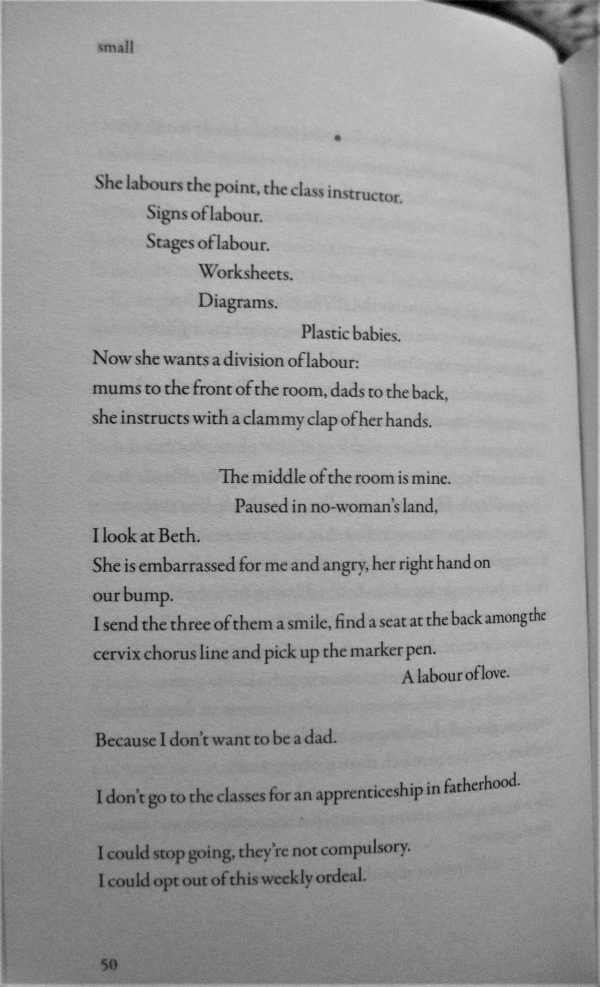

There are two intriguing structural choices that make small stand out. The first you’d notice from opening the book at random, or to page 1. It is written in a hybrid form, the phrases and sentences laid out more like poetry. Although there are some traditional expository paragraphs, more often the words are in stanzas or indented. Here’s an example of what this looks like on the page. It also happens to be from one of the most ironically funny parts of the book, when Lynch is grouped in with the dads at an antenatal class:

It’s a fast-flowing, artful style that may remind readers of Bernardine Evaristo’s work (and indeed, Evaristo gives one of the puffs). The second interesting decision was to make the book turn on a revelation: at the exact halfway mark we learn that, initially, the couple intended to have opposite roles: Lynch tried to get pregnant with Beth’s baby, but miscarried. Making this the pivot point of the memoir emphasizes the struggle and grief of this experience, even though we know that it had a happy ending.

With thanks to Brazen Books for the free copy for review.

How We Do Family by Trystan Reese

We mostly have Trystan Reese to thank for the existence of a pregnant man emoji. A community organizer who works on anti-racist and LGBTQ justice campaigns, Reese is a trans man married to a man named Biff. They expanded their family in two unexpected ways: first by adopting Biff’s niece and nephew when his sister’s situation of poverty and drug abuse meant she couldn’t take care of them, and then by getting pregnant in the natural (is that even the appropriate word?) way.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

All along, Reese sought to be transparent about the journey, with a crowdfunding project and podcast ahead of the adoption, and media coverage of the pregnancy. This opened the family up to a lot of online hatred. I found myself most interested in the account of the pregnancy itself, and how it might have healed or exacerbated a sense of bodily trauma. Reese was careful to have only in-the-know and affirming people in the delivery room so there would be no surprises for anyone. His doctor was such an ally that he offered to create a more gender-affirming C-section scar (vertical rather than horizontal) if it came to it. How to maintain a sense of male identity while giving birth? Well, Reese told Biff not to look at his crotch during the delivery, and decided not to breastfeed.

I realized when reading this and Detransition, Baby that my view of trans people is mostly post-op because of the only trans person I know personally, but a lot of people choose never to get surgical confirmation of gender (or maybe surgery is more common among trans women?). We’ve got to get past the obsession with genitals. As Reese writes, “we are just loving humans, like every human throughout all of time, who have brought a new life into this world. Nothing more than that, and nothing less. Just humans.”

This is a very fluid, quick read that recreates scenes and conversations with aplomb, and there are self-help sections after most chapters about how to be flexible and have productive dialogue within a family and with strangers. If literary prose and academic-level engagement with the issues are what you’re after, you’d want to head to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts instead, but I also appreciated Reese’s unpretentious firsthand view.

And here’s further evidence of my own bias: the whole time I was reading, I felt sure that Reese must be the figure on the right with reddish hair, since that looked like a person who could once have been a woman. But when I finished reading I looked up photos; there are many online of Reese during pregnancy. And NOPE, he is the bearded, black-haired one! That’ll teach me to make assumptions. (Published by The Experiment. Read via NetGalley)

Plus a bonus essay from the Music.Football.Fatherhood anthology, DAD:

“A Journey to Gay Fatherhood: Surrogacy – The Unimaginable, Manageable” by Michael Johnson-Ellis

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

The author and his husband Wes had both previously been married to women before they came out. Wes already had a daughter, so they decided Johnson-Ellis would be the genetic father the first time. They then had different egg donors for their two children, but used the same surrogate for both pregnancies. I was astounded at the costs involved: £32,000 just to bring their daughter into being. And it’s striking both how underground the surrogacy process is (in the UK it’s illegal to advertise for a surrogate) and how exclusionary systems are – the couple had to fight to be in the room when their surrogate gave birth, and had to go to court to be named the legal guardians when their daughter was six weeks old. Since then, they’ve given testimony at the Houses of Parliament and become advocates for UK surrogacy.

(I have a high school acquaintance who has gone down this route with his husband – they’re about to meet their daughter and already have a two-year-old son – so I was curious to know more about it, even though their process in the USA might be subtly different.)

On the subject of queer family-making, I have also read: The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson ( ) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg (

) and The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg ( ).

).

If you read just one … Claire Lynch’s small was the one I enjoyed most as a literary product, but if you want to learn more about the options and process you might opt for Jennifer Berney’s The Other Mothers; if you’re particularly keen to explore trans issues and LGTBQ activism, head to Trystan Reese’s How We Do Family.

Have you read anything on this topic?

Reading Ireland Month: Baume, Kennefick, Ní Ghríofa, O’Farrell

Reading Ireland Month is hosted each March by Cathy of 746 Books. This year I read works by four Irish women: a meditation on birds and craft, hard-hitting poems about body issues, autofiction that incorporates biography and translation to consider the shape of women’s lives across the centuries, and a novel that jets between Hong Kong and Scotland. Two of these were sent to me as part of the Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist. I have some Irish music lined up to listen to (Hallow by Duke Special, At Swim by Lisa Hannigan, Chop Chop by Bell X1, Magnetic North by Iain Archer) and I’m ready to tell you all about these four books.

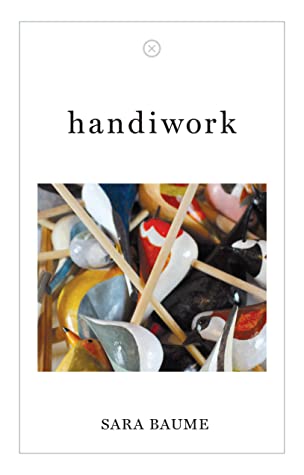

handiwork by Sara Baume (2020)

Back in February 2016, I reviewed Baume’s debut novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, for Third Way magazine. A dark story of a middle-aged loner and his adopted dog setting off on a peculiar road trip, it was full of careful nature imagery. “I’ve always noticed the smallest, quietest things,” the narrator, Ray, states. The same might be said of Baume, who is a visual artist as well as an author and put together this gently illuminating book over the course of 2018, at the same time as she was working on several sculptural installations. In short sections of a paragraph or two, or sometimes no more than a line, she describes her daily routines in her home workspaces: in the morning she listens to barely audible talk radio as she writes, while the afternoons are for carving and painting.

Back in February 2016, I reviewed Baume’s debut novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, for Third Way magazine. A dark story of a middle-aged loner and his adopted dog setting off on a peculiar road trip, it was full of careful nature imagery. “I’ve always noticed the smallest, quietest things,” the narrator, Ray, states. The same might be said of Baume, who is a visual artist as well as an author and put together this gently illuminating book over the course of 2018, at the same time as she was working on several sculptural installations. In short sections of a paragraph or two, or sometimes no more than a line, she describes her daily routines in her home workspaces: in the morning she listens to barely audible talk radio as she writes, while the afternoons are for carving and painting.

Working with her hands is a family tradition passed down from her grandfather and father, who died in the recent past – of lung cancer from particles he was exposed to at the sandstone quarry where he worked. Baume has a sense of responsibility for how she spends her time and materials. Concern about waste is at odds with a drive for perfection: she discarded her first 100 plaster birds before she was happy with the series used to illustrate this volume. Snippets of craft theory, family memories, and trivia about bird migration and behaviour are interspersed with musings on what she makes. The joy of holding a physical object in the hand somehow outweighs that of having committed virtual words to a hard drive.

Despite the occasional lovely line, this scattered set of reflections doesn’t hang together. The bird facts, in particular, feel shoehorned in for symbolism, as in Colum McCann’s Apeirogon. It’s a shame, as from the blurb I thought this book couldn’t be better suited to my tastes. Ultimately, as with Spill, Baume’s prose doesn’t spark much for me.

Favorite lines:

“Most of the time spent making is spent, in fact, in the approach.”

“I must stop once the boredom becomes intolerable, knowing that if I plunge on past this point I will risk arriving at resentment”

“What we all shared – me, my dad, his dad – was a suspicion of modern life, a loathing of fashion, a disappointment with the new technologies and a preference for the ad hoc contraptions of the past”

“The glorious, crushing, ridiculous repetition of life.”

With thanks to Tramp Press and FMcM Associates for the free copy for review. handiwork is on the Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist.

Eat or We Both Starve by Victoria Kennefick (2021)

This audacious debut collection of fleshly poems is the best I’ve come across so far this year. The body is presented as a battleground: for the brain cancer that takes the poet’s father; for disordered eating that entwines with mummy issues; for the restructuring of pregnancy. Families break apart and fuse into new formations. Cannibalism and famine metaphors dredge up emotional states and religious doctrines.

This audacious debut collection of fleshly poems is the best I’ve come across so far this year. The body is presented as a battleground: for the brain cancer that takes the poet’s father; for disordered eating that entwines with mummy issues; for the restructuring of pregnancy. Families break apart and fuse into new formations. Cannibalism and famine metaphors dredge up emotional states and religious doctrines.

Where did I start?

Yes, with the heart, enlarged,

its chambers stretched through caring.

[…]

Oh is it in defiance or defeat, I don’t know,

I eat it anyway, raw, still warm.

The size of my fist, I love it.

(from the opening poem, “Learning to Eat My Mother, where My Mother Is the Teacher”)

Meat avoidance goes beyond principled vegetarianism to become a phobia. Like the female saints, the speaker will deny herself until she achieves spiritual enlightenment.

The therapist taps my shoulders, my head, my knees,

tells me I was a nun once, very strict.

This makes sense; I know how cleanly I like

to punish myself.

(from “Alternative Medicine”)

The title phrase comes from “Open Your Mouth,” in which the god Krishna, as a toddler, nourishes his mother with clay. A child feeding its mother reverses the expected situation, which is described in one of the book’s most striking poems, “Researching the Irish Famine.” The site of an old workhouse divulges buried horrors: “Mothers exhausted their own bodies / to produce milk. […] The starving / human / literally / consumes / itself.”

Corpses and meals; body odour and graves. There’s a pleasingly morbid cast to this collection, but it also has its lighter moments: the sexy “Paris Syndrome,” the low-stakes anxiety over pleasing one’s mother in “Guest Room,” and the playful closer, “Prayer to Audrey Hepburn” (“O Blessed Audrey of the feline eye-flick, jutting / bones, slim-hipped androgyny of war-time rationing”). Rich with imagery and alliteration, this is just my kind of poetry. Verse readalikes would include The Air Year by Caroline Bird, Flèche by Mary Jean Chan, and Tongues of Fire by Seán Hewitt, while in prose I was also reminded of Milk Fed by Melissa Broder (review coming soon) and Sanatorium by Abi Palmer.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review. This comes out on the 25th.

A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa (2020)

“This is a female text.” In an elegant loop, Ní Ghríofa begins and ends with this line, and uses it as a refrain throughout. What is the text? It is this book, yes, as well as the 18th-century Irish-language poem that becomes an obsession for the author/narrator, “The Keen for Art Ó Laoghaire” by Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill; however, it is also the female body, its milk and blood just as significant for storytelling as any ink.

“This is a female text.” In an elegant loop, Ní Ghríofa begins and ends with this line, and uses it as a refrain throughout. What is the text? It is this book, yes, as well as the 18th-century Irish-language poem that becomes an obsession for the author/narrator, “The Keen for Art Ó Laoghaire” by Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill; however, it is also the female body, its milk and blood just as significant for storytelling as any ink.

Because the protagonist’s name is the same as the author’s, I took her experiences at face value. As the narrative opens in 2012, Ní Ghríofa and her husband have three young sons and life for her is a list of repetitive household tasks that must be completed each day. She donates pumped breast milk for premature babies as a karmic contribution to the universe: something she can control when so much around her she feels she can’t, like frequent evictions and another pregnancy. Reading Eibhlín Dubh’s lament for her murdered husband, contemplating a new translation of it, and recreating her life from paltry archival fragments: these tasks broaden her life and give an intellectual component to complement the bodily one.

My weeks are decanted between the twin forces of milk and text, weeks that soon pour into months, and then into years. I make myself a life in which whenever I let myself sit, it is to emit pale syllables of milk, while sipping my own dark sustenance from ink. […] I skitter through chaotic mornings of laundry and lunchboxes and immunisations, always anticipating my next session at the breast-pump, because this is as close as I get to a rest. To sit and read while bound to my insatiable machine is to leave my lists behind and stroll instead through doors opened by Eibhlín Dubh.

Ní Ghríofa remembers other times in her life in an impressionistic stream: starting a premed course at university, bad behaviour that culminated in suicidal ideation, a near-collision on a highway, her daughter’s birth by emergency C-section, finally buying a house and making it a home by adopting a stray kitten and planting a bee-friendly garden. You can tell from the precision of her words that Ní Ghríofa started off as a poet, and I loved how she writes about her own life. I had little interest in Eibhlín Dubh’s story, but maybe it’s enough for her to be an example of women “cast once more in the periphery of men’s lives.” It’s a book about women’s labour – physical and emotional – and the traces of it that remain. I recommend it alongside I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Mother Ship by Francesca Segal.

With thanks to Tramp Press and FMcM Associates for the free copy for review. A Ghost in the Throat is on the Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist.

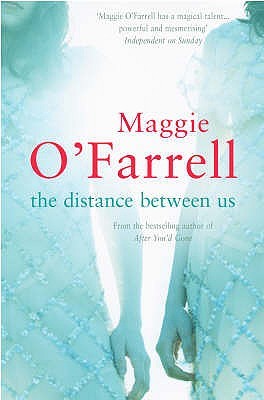

The Distance Between Us by Maggie O’Farrell (2004)

This is the earliest work of O’Farrell’s that I’ve read – it was her third novel, following After You’d Gone and My Lover’s Lover (I finally found those two at a charity shop last year and I’m saving them for a rainy day). It took me a long time to get into this one. It’s delivered in bitty sections that race between characters and situations, not generally in chronological order. It’s not until nearly the halfway point that you get a sense of how it all fits together.

This is the earliest work of O’Farrell’s that I’ve read – it was her third novel, following After You’d Gone and My Lover’s Lover (I finally found those two at a charity shop last year and I’m saving them for a rainy day). It took me a long time to get into this one. It’s delivered in bitty sections that race between characters and situations, not generally in chronological order. It’s not until nearly the halfway point that you get a sense of how it all fits together.

Although there are many secondary characters, the two main strands belong to Jake, a young white filmmaker raised in Hong Kong by a bohemian mother, and Stella, a Scottish-Italian radio broadcaster. When a Chinese New Year celebration turns into a stampede, Jake and his girlfriend narrowly escape disaster and rush into a commitment he’s not ready for. In the meantime, Stella gets spooked by a traumatic flash from her childhood and flees London for a remote Scottish hotel. She’s very close to her older sister, Nina, who was deathly ill as a child (O’Farrell inserts a scene I was familiar with from I Am, I Am, I Am, when she heard a nurse outside her room chiding a noisy visitor, “There’s a little girl dying in there”), but now it’s Nina who will have to convince Stella to take the chance at happiness that life is offering.

In the end, this felt like a rehearsal for This Must Be the Place; it has the myriad settings (e.g., here, Italy, Wales and New Zealand are also mentioned) but not the emotional heft. With a setup like this, you sort of know where things are going, don’t you? Despite Stella’s awful secret, she is as flat a character as Jake. Simple boy-meets-girl story lines don’t hold a lot of appeal for me now, if they ever did. Still, the second half was a great ride.

Also, I’ve tried twice over the past year, but couldn’t get further than page 80 in The Wild Laughter by Caoilinn Hughes (2020), a black comedy about two brothers whose farmer father goes bankrupt and gets a terminal diagnosis. It’s a strangely masculine book (though in some particulars very similar to Scenes of a Graphic Nature) and I found little to latch on to. This was a disappointment as I’d very much enjoyed Hughes’s debut, Orchid & the Wasp, and this second novel is now on the Dylan Thomas Prize longlist.

What have you been picking up for Reading Ireland Month?

Recapping the Not the Wellcome Prize Blog Tour Reviews

It’s hard to believe the Not the Wellcome Prize blog tour is over already! It has been a good two weeks of showcasing some of the best medicine- and health-themed books published in 2019. We had some kind messages of thanks from the authors, and good engagement on Twitter, including from publishers and employees of the Wellcome Trust. Thanks to the bloggers involved in the tour, and others who have helped us with comments and retweets.

This weekend we as the shadow panel (Annabel of Annabookbel, Clare of A Little Blog of Books, Laura of Dr. Laura Tisdall, Paul of Halfman, Halfbook and I) have the tough job of choosing a shortlist of six books, which we will announce on Monday morning. I plan to set up a Twitter poll to run all through next week. The shadow panel members will vote to choose a winner, with the results of the Twitter poll serving as one additional vote. The winner will be announced a week later, on Monday the 11th.

First, here’s a recap of the 19 terrific books we’ve featured, in chronological blog tour order. In fiction we’ve got: novels about child development, memory loss, and disturbed mental states; science fiction about AI and human identity; and a graphic novel set at a small-town medical practice. In nonfiction the topics included: anatomy, cancer, chronic pain, circadian rhythms, consciousness, disability, gender inequality, genetic engineering, premature birth, sleep, and surgery in war zones. I’ve also appended positive review coverage I’ve come across elsewhere, and noted any other awards these books have won or been nominated for. (And see this post for a reminder of the other 56 books we considered this year through our mega-longlist.)

Notes Made While Falling by Jenn Ashworth & The Remarkable Life of the Skin by Monty Lyman: Simon’s reviews

Notes Made While Falling by Jenn Ashworth & The Remarkable Life of the Skin by Monty Lyman: Simon’s reviews

*Monty Lyman was shortlisted for the 2019 Royal Society Science Book Prize.

[Bookish Beck review of the Ashworth]

[Halfman, Halfbook review of the Lyman]

Exhalation by Ted Chiang & A Good Enough Mother by Bev Thomas: Laura’s reviews

Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson & War Doctor by David Nott: Jackie’s reviews

Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson & War Doctor by David Nott: Jackie’s reviews

*Sinéad Gleeson was shortlisted for the 2020 Rathbones Folio Prize.

[Rebecca’s Goodreads review of the Gleeson]

[Kate Vane’s review of the Gleeson]

[Lonesome Reader review of the Gleeson]

[Rebecca’s Shiny New Books review of the Nott]

Vagina: A Re-education by Lynn Enright: Hayley’s Shiny New Books review

Galileo’s Error by Philip Goff: Peter’s Shiny New Books review

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal & The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Rebecca’s reviews

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal & The Lady Doctor by Ian Williams: Rebecca’s reviews

[A Little Blog of Books review of the Segal]

[Annabookbel review of the Williams]

Chasing the Sun by Linda Geddes & The Nocturnal Brain by Guy Leschziner: Paul’s reviews

[Bookish Beck review of the Geddes]

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado-Pérez: Katie’s review

Invisible Women by Caroline Criado-Pérez: Katie’s review

*Caroline Criado-Pérez won the 2019 Royal Society Science Book Prize.

[Liz’s Shiny New Books review]

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg: Kate’s review

Machines Like Me by Ian McEwan: Kate’s review

Hacking Darwin by Jamie Metzl & The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa: Annabel’s reviews

Hacking Darwin by Jamie Metzl & The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa: Annabel’s reviews

*Yoko Ogawa is shortlisted for this year’s International Booker Prize.

[Lonesome Reader review of the Ogawa]

The Body by Bill Bryson & The World I Fell Out Of by Melanie Reid: Clare’s reviews

The Body by Bill Bryson & The World I Fell Out Of by Melanie Reid: Clare’s reviews

[Bookish Beck review of the Bryson]

[Rebecca’s Goodreads review of the Reid]

And there we have it: the Not the Wellcome Prize longlist. I hope you’ve enjoyed following along with the reviews. Look out for the shortlist, and your chance to vote for the winner, here and via Twitter on Monday.

Which book(s) are you rooting for?

Best of 2019: Nonfiction

For me, 2019 has been a more memorable year for nonfiction than for fiction. Like I did last year, I’ve happened to choose 12 favorite nonfiction books – though after some thematic grouping this has ended up as a top 10 list. Bodies, archaeology, and the environmental crisis are recurring topics, reflecting my own interests but also, I think, something of the zeitgeist.

Let the countdown begin!

Because Internet: Understanding how language is changing by Gretchen McCulloch: Surprisingly fascinating stuff, even for a late adopter of technology. The Internet popularized informal writing and quickly incorporates changes in slang and cultural references. The book addresses things you may never have considered, like how we convey tone of voice through what we type and how emoji function as the gestures of the written word. Bursting with geeky enthusiasm.

Because Internet: Understanding how language is changing by Gretchen McCulloch: Surprisingly fascinating stuff, even for a late adopter of technology. The Internet popularized informal writing and quickly incorporates changes in slang and cultural references. The book addresses things you may never have considered, like how we convey tone of voice through what we type and how emoji function as the gestures of the written word. Bursting with geeky enthusiasm.

-

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie: A fusion of autobiography with nature and travel writing – two genres that are too often dominated by men. Jamie has a particular interest in birds, islands, archaeology and the oddities of the human body, all subjects that intrigue me. There is beautiful nature writing to be found in this volume, as you might expect, but also relatable words on the human condition.

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie: A fusion of autobiography with nature and travel writing – two genres that are too often dominated by men. Jamie has a particular interest in birds, islands, archaeology and the oddities of the human body, all subjects that intrigue me. There is beautiful nature writing to be found in this volume, as you might expect, but also relatable words on the human condition.

-

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal: A visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of the author’s daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU. Segal describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn between writing and motherhood, and crafts twinkly pen portraits of others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums.

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal: A visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of the author’s daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU. Segal describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn between writing and motherhood, and crafts twinkly pen portraits of others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums.

-

Surrender: Mid-Life in the American West by Joanna Pocock: Prompted by two years spent in Missoula, Montana and the disorientation felt upon a return to London, this memoir-in-essays varies in scale from the big skies of the American West to the smallness of one human life and the experience of loss and change. This is an elegantly introspective work that should engage anyone interested in women’s life writing and the environmental crisis.

Surrender: Mid-Life in the American West by Joanna Pocock: Prompted by two years spent in Missoula, Montana and the disorientation felt upon a return to London, this memoir-in-essays varies in scale from the big skies of the American West to the smallness of one human life and the experience of loss and change. This is an elegantly introspective work that should engage anyone interested in women’s life writing and the environmental crisis.

- (A tie) Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson / The Undying by Anne Boyer / Notes Made while Falling by Jenn Ashworth: Trenchant autobiographical essays about female pain. All three feel timely and inventive in how they bring together disparate topics to explore the possibilities and limitations of women’s bodies. A huge theme in life writing in the last couple of years and a great step toward trauma and chronic pain being taken seriously. (See also Notes to Self by Emilie Pine and the forthcoming Pain Studies by Lisa Olstein.)

-

Time Song: Searching for Doggerland by Julia Blackburn: Deep time is another key topic this year. Blackburn follows her curiosity wherever it leads as she does research into millions of years of history, including the much shorter story of human occupation. The writing is splendid, and the dashes of autobiographical information are just right, making her timely/timeless story personal. This would have been my Wainwright Prize winner.

Time Song: Searching for Doggerland by Julia Blackburn: Deep time is another key topic this year. Blackburn follows her curiosity wherever it leads as she does research into millions of years of history, including the much shorter story of human occupation. The writing is splendid, and the dashes of autobiographical information are just right, making her timely/timeless story personal. This would have been my Wainwright Prize winner.

-

The Seafarers: A Journey among Birds by Stephen Rutt: The young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. Discussion of the environmental threats that hit these species hardest, such as plastic pollution, makes for a timely tie-in to wider issues. The prose is elegantly evocative, and especially enjoyable because I’ve been to a lot of the island locations.

The Seafarers: A Journey among Birds by Stephen Rutt: The young naturalist travelled the length and breadth of the British Isles – from Skomer to Shetland – courting encounters with seabirds. Discussion of the environmental threats that hit these species hardest, such as plastic pollution, makes for a timely tie-in to wider issues. The prose is elegantly evocative, and especially enjoyable because I’ve been to a lot of the island locations.

-

Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene: In 2015 the author’s two-year-old daughter, Greta, was fatally struck in the head by a brick that crumbled off an eighth-story Manhattan windowsill. Music journalist Greene explores all the ramifications of grief. I’ve read many a bereavement memoir and can’t remember a more searing account of the emotions and thoughts experienced moment to moment. The whole book has an aw(e)ful clarity to it.

Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene: In 2015 the author’s two-year-old daughter, Greta, was fatally struck in the head by a brick that crumbled off an eighth-story Manhattan windowsill. Music journalist Greene explores all the ramifications of grief. I’ve read many a bereavement memoir and can’t remember a more searing account of the emotions and thoughts experienced moment to moment. The whole book has an aw(e)ful clarity to it.

-

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson: Bryson is back on form indulging his layman’s curiosity. Without ever being superficial or patronizing, he gives a comprehensive introduction to every organ and body system. He delights in our physical oddities, and his sense of wonder is contagious. Shelve this next to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande in a collection of books everyone should read – even if you don’t normally choose nonfiction.

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson: Bryson is back on form indulging his layman’s curiosity. Without ever being superficial or patronizing, he gives a comprehensive introduction to every organ and body system. He delights in our physical oddities, and his sense of wonder is contagious. Shelve this next to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande in a collection of books everyone should read – even if you don’t normally choose nonfiction.

-

Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places by Julian Hoffman: Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This exquisitely written book is about taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. So, if you read one 2019 release, make it this one.

Irreplaceable: The Fight to Save Our Wild Places by Julian Hoffman: Species and habitat loss are hard to comprehend even when we know the facts. This exquisitely written book is about taking stock, taking responsibility, and going beyond the numbers to tell the stories of front-line conservation work. Irreplaceable is an elegy of sorts, but, more importantly, it’s a call to arms. It places environmentalism in the hands of laypeople and offers hope that in working together in the spirit of defiance we can achieve great things. So, if you read one 2019 release, make it this one.

(Books not pictured were read from the library or on Kindle.)

What were some of your top nonfiction reads of the year?

Upcoming posts:

28th: Runners-up

29th: Other superlatives and some statistics

30th: Best backlist reads

31st: The final figures on my 2019 reading

Three Review Books: Brian Kimberling, Jessica Pan & Francesca Segal

Three May–June releases: A fish-out-of-water comic novel about teaching English in Prague; and memoirs about acting like an extrovert and giving birth to premature twins.

Goulash by Brian Kimberling

“Look where we are. East meets West. Communism meets capitalism.” In 1998 Elliott Black leaves Indiana behind for a couple of years to teach English in Prague. The opening sequence, in which he discovers that his stolen shoes have been incorporated into an art installation, is an appropriate introduction to a country where bizarre things happen. Elliott doesn’t work for a traditional language school; his students are more likely to be people he meets in the pub or tobacco company executives. Their quirky, deadpan conversations are the highlight of the book.

“Look where we are. East meets West. Communism meets capitalism.” In 1998 Elliott Black leaves Indiana behind for a couple of years to teach English in Prague. The opening sequence, in which he discovers that his stolen shoes have been incorporated into an art installation, is an appropriate introduction to a country where bizarre things happen. Elliott doesn’t work for a traditional language school; his students are more likely to be people he meets in the pub or tobacco company executives. Their quirky, deadpan conversations are the highlight of the book.

Elliott starts dating a fellow teacher from England, Amanda (she “looked like azaleas in May and she spoke like the BBC World Service”), who also works as a translator. They live together in an apartment they call Graceland. Much of this short novel is about their low-key, slightly odd adventures, together and separately, while the epilogue sees Elliott looking back at their relationship from many years later.

I was tickled by a number of the turns of phrase, but didn’t feel particularly engaged with the plot, which was inspired by Kimberling’s own experiences living in Prague.

With thanks to Tinder Press for a proof copy to review.

Favorite passages:

“Sorrowful stories like airborne diseases made their way through the windows and under the doorframe, bubbled up like the bathtub drain. It was possible to fill Graceland with light and color and music and the smell of good food, and yet the flat was like a patient with some untreatable condition, and we got tired of palliative care.”

“‘It’s good to be out of Prague,’ he said. ‘Every inch drenched in blood and steeped in alchemy, with a whiff of Soviet body odor.’ ‘You should write for Lonely Planet,’ I said.”

Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come: An Introvert’s Year of Living Dangerously by Jessica Pan

Like Jessica Pan, I’m a shy introvert (a “shintrovert”) as well as an American in the UK, so I was intrigued to see the strategies she employed and the experiences she sought out during a year of behaving like an extrovert. She forced herself to talk to strangers on the tube, give a talk at London’s Union Chapel as part of the Moth, use friendship apps to make new girlfriends, do stand-up comedy and improv, go to networking events, take a holiday to an unknown destination, eat magic mushrooms, and host a big Thanksgiving shindig.

Like Jessica Pan, I’m a shy introvert (a “shintrovert”) as well as an American in the UK, so I was intrigued to see the strategies she employed and the experiences she sought out during a year of behaving like an extrovert. She forced herself to talk to strangers on the tube, give a talk at London’s Union Chapel as part of the Moth, use friendship apps to make new girlfriends, do stand-up comedy and improv, go to networking events, take a holiday to an unknown destination, eat magic mushrooms, and host a big Thanksgiving shindig.

Like Help Me!, which is a fairly similar year challenge book, it’s funny, conversational and compulsive reading that was perfect for me to be picking up and reading in chunks while I was traveling. Although I don’t think I’d copy any of Pan’s experiments – there’s definitely a cathartic element to reading this; if you’re also an introvert, you’ll feel nothing but relief that she’s done these things so you don’t have to – I can at least emulate her in initiating deeper conversations with friends and pushing myself to attend literary and networking events instead of just staying at home.

With thanks to Doubleday UK for a proof copy to review.

Mother Ship by Francesca Segal

I’m a big fan of Segal’s novels, especially The Innocents, one of the loveliest debut novels of the last decade, so I was delighted to hear she was coming out with a health-themed memoir about giving birth to premature twins. Mother Ship is a visceral diary of the first eight weeks in the lives of her daughters, who were born by Caesarean section at 29 weeks in October 2015 and spent the next two months in the NICU, “an extremely well-funded prison or perhaps more accurately a high-tech zoo.”

Segal strives to come to terms with this unnatural start to motherhood. “Taking my unready daughters from within me felt not like a birth but an evisceration,” she writes; “my children do not appear to require mothering. Instead they need sophisticated medical intervention.” She describes with tender precision the feeling of being torn: between the second novel she’d been in the middle of writing and the all-consuming nature of early parenthood; and between her two girls (known for much of the book as “A-lette” and “B-lette”), who are at one point separated in different hospitals.

Spotted at Philadelphia airport.

As well as portraying her own state of mind, Segal crafts twinkly pen portraits of the others she encountered in the NICU, including the staff but especially her fellow preemie mums, who met in a “milking shed” where they pumped breast milk for the babies they were so afraid of losing that they resisted naming. (Though it was touch and go for a while, A-lette and B-lette finally earned the names Raffaella and Celeste and came home safely.) Female friendship is a subsidiary theme in this exploration of desperate love and helplessness. The layman’s look at the inside workings of medicine would have made this one of my current few favorites for next year’s Wellcome Book Prize (which, alas, is on hiatus). After encountering some unpleasant negativity about the NHS in a recent read, I was relieved to find that Segal’s outlook is pure gratitude.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus for the free copy for review.

Would you be interested in reading one or more of these?

Review: English Animals by Laura Kaye

“Maybe we can see that the animals are like us, or we are like animals.”

Laura Kaye’s impressive debut novel, English Animals, is a fresh take on themes of art, sex, violence and belonging. It has particular resonance in the wake of Brexit, showing the apparent lack of a cohesive English identity in spite of sometimes knee-jerk nationalism.

The novel takes place within roughly a year and is narrated by Mirka Komárova, a 19-year-old Slovakian who left home suddenly after an argument with her parents and arrives in the English countryside to work for thirty-somethings Richard and Sophie Parker. She doesn’t know what to expect from her new employers: “Richard and Sophie sounded like good names for good people. But they could be anything, they could be completely crazy.”

The novel takes place within roughly a year and is narrated by Mirka Komárova, a 19-year-old Slovakian who left home suddenly after an argument with her parents and arrives in the English countryside to work for thirty-somethings Richard and Sophie Parker. She doesn’t know what to expect from her new employers: “Richard and Sophie sounded like good names for good people. But they could be anything, they could be completely crazy.”

It’s a live-in governess-type arrangement, and yet there are no children – Mirka later learns that Sophie is having trouble getting pregnant. Instead Mirka drives the volatile Parkers to the pub so they can get drunk whenever they want, and also helps with their various money-making ventures: cooking and cleaning for B&B guests and the summer’s wedding parties, serving as a beater for pheasant shoots, and assisting with Richard’s taxidermy business. Her relationship with them remains uncertain: she’s not a servant but not quite an equal either; it’s a careful friendship powered by jokes with Richard and cryptic crossword clues with Sophie.

At first Mirka seems disgusted by Sophie’s shabby family home and the many animals around the place, both living and dead. Initially squeamish about skinning animal corpses, she gets used to it as taxidermy becomes her artistic expression. Taking inspiration from whimsical Victorian portraits of dead animals in costume, she makes intricate modern tableaux with names like Mice Raving, Freelance Squirrels and Rats at the Office Party. When her art catches the eye of a London agent, she starts preparing her pieces for an exhibit and is the subject of a magazine profile. The interviewer writes this about her:

Mirka is someone who understands the philosophical nature of her art. How, in our strange condition of being simultaneously within and outside the animal kingdom, we invest taxidermy with our longing for permanence.

I loved the level of detail about Mirka’s work – it’s rare to encounter such a precise account of handiwork in fiction, as opposed to in nonfiction like Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with Amber Eyes and David Esterly’s The Lost Carving; Kaye herself is a potter, which might explain it – and I appreciated the many meanings that dead animals take on in the novel. They’re by turns food, art objects and sacrificial victims. Taxidermy is a perfect juxtaposition of physicality and the higher echelons of art, a canny way of blending death and beauty.

But of course the human residents of this community also fall into the title’s category: Many of them are what you might call ‘beastly’, and the threat of violence is never far away given Richard and Sophie’s argumentativeness. A promiscuous blonde, Sophie reminded me of Daisy in The Great Gatsby, so often described as careless: “You are a dangerous person, Sophie,” Mirka says. “Don’t say that. I didn’t mean to hurt anything.” Mirka replies, “You don’t care about other things. Everything is a game. Everyone is a toy for you to play with.”

The two different blurbs I’ve seen for the book both give too much away, so I will simply say that there’s an air of sexual tension and latent hostility surrounding this semi-isolated home, and it’s intriguing to watch the dynamic shift between Richard, Sophie and Mirka. I felt that I never quite knew what would happen or how far Kaye would take things.

I did have a few minor misgivings, though: sometimes Mirka’s narration reads like a stilted translation into English, rather than a fluent outpouring; there’s a bit too much domestic detail and heavy-handed symbolism; and the themes of xenophobia and homophobia might have been introduced more subtly, rather than using certain characters as overt mouthpieces.

All the same, I read this with great interest and curiosity throughout. It’s a powerful look at assumptions versus reality, how we approach the Other, and the great effort it takes to change; it’s easier to remain trapped in the roles we’ve acquired. I’d recommend this to readers of Polly Samson, Francesca Segal and even Rachel Johnson (the satire Shire Hell). In particular, I was reminded of Shelter by Jung Yun and Little Children by Tom Perrotta: though suburban in setting, they share Kaye’s preoccupations with sex and violence and the ways we try to hide our true selves beneath a façade of conformity.

This is one of the most striking debut novels I’ve encountered in recent years; it’s left me eager to see what Laura Kaye will do next.

English Animals was published by Little, Brown UK on January 12th. My thanks to Hayley Camis for the review copy.

My rating:

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the blog tour for English Animals. See below for details of where other reviews and features have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Rightly likened to Of Mice and Men, this is an engrossing short novel about two brothers, Neil and Calum, tasked with climbing trees and gathering the pinecones of a wealthy Scottish estate. They will be used to replant the many woodlands being cut down to fuel the war effort. Calum, the younger brother, is physically and intellectually disabled but has a deep well of compassion for living creatures. He has unwittingly made an enemy of the estate’s gamekeeper, Duror, by releasing wounded rabbits from his traps. Much of the story is taken up with Duror’s seemingly baseless feud against the brothers – though we’re meant to understand that his bedbound wife’s obesity and his subsequent sexual frustration may have something to do with it – as well as with Lady Runcie-Campbell’s class prejudice. Her son, Roderick, is an unexpected would-be hero and voice of pure empathy. I read this quickly, with grim fascination, knowing tragedy was coming but not quite how things would play out. The introduction to Canongate’s Canons Collection edition is by actor Paul Giamatti, of all people. (Secondhand – Community Furniture Project, Newbury)

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

Eric and Mabel moved from the Midlands to run a hotel on a remote Scottish island. He places an advertisement in select London periodicals to lure in some Christmas-haters for the holidays and attracts a motley group: a bereaved former soldier writing a biography of General Gordon, a pair of actors known only for commercials, a psychoanalyst, and a department store buyer looking for a novel sweater pattern. Mabel decides she’s had enough and flees the island just as the guests start arriving. One guest is stalking another; one has history on the island. And all along, there are hints that this is a site of major selkie activity. I found it jarring how the novella moved from Shena Mackay-like social comedy into magic realism and doubt I’ll read more by Ellis (I’d already read one volume of

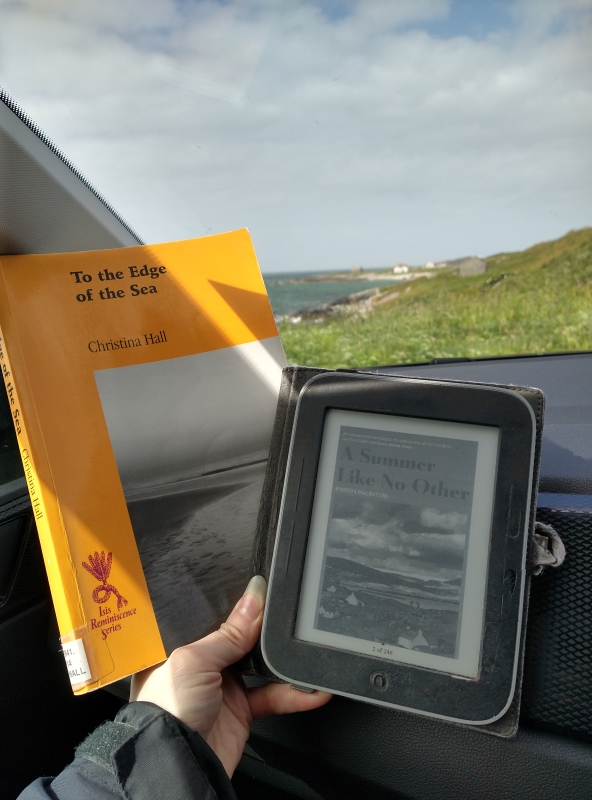

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)

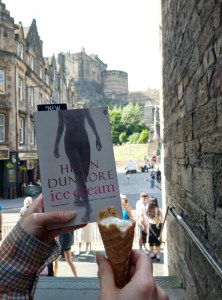

The many Gaelic phrases, defined in footnotes, help to create the atmosphere. The chapter epigraphs from the legend of Oisín (son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill) and Tír Na nÓg, the land of eternal youth, heighten the contrast between Colin’s idealism and the reality of this life-changing season. I think this is the first book I’ve read that was originally published in Gaelic and I hope it will find readers far beyond its island niche. (BookSirens)  1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

1) Our transit through Edinburgh was brief and muggy, but we made sure to leave just enough time to queue for cones at Mary’s Milk Bar, which has the most interesting flavours you’ll find anywhere. Pictured, though half eaten, are my one scoop of Earl Grey and peach sorbet and one scoop of fig and cardamom ice cream. When we returned to Edinburgh to return the car at the end of our trip, I took the train home by myself but C stayed on for a conference, during which he treated himself to another round at Mary’s.

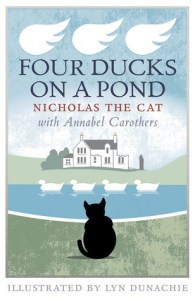

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)

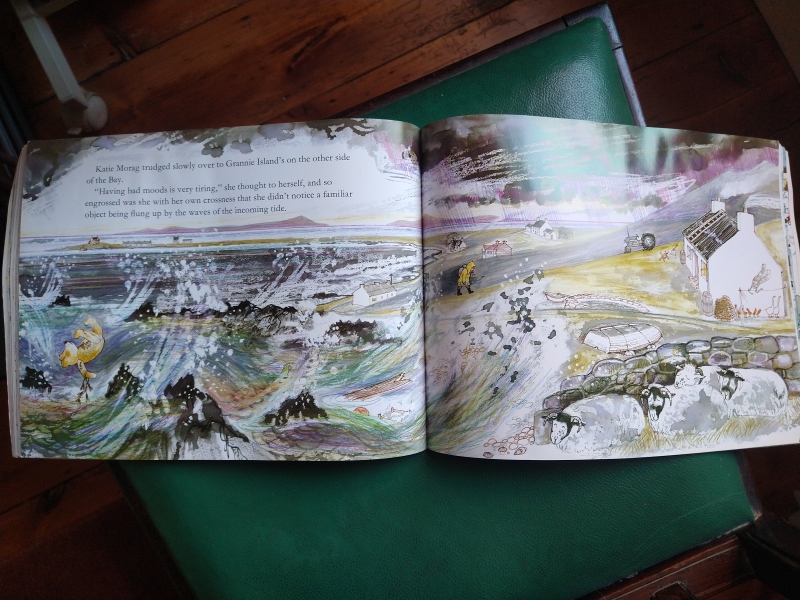

A quaint short memoir set in the 1950s on the island of Mull (which we sailed past on our way to and from the Outer Hebrides). It’s narrated in tongue-in-cheek fashion by Nicholas the Cat, who pals around with the farm’s dogs, horse and goats and comments on the doings of its human inhabitants, such as “Puddy” (Carothers), a war widow, and her daughter Fionna, who goes away to school. “We understand so much about them, yet they understand so little about us,” he opines. Indeed, the animals are all observant and can communicate with each other. Corrieshellach is a fine horse taken to compete in shows. The goats are lucky to escape with their lives after a local outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease among livestock. Nicholas grows fat on rabbits and fathers several litters. He voices some traditional views (the Clearances: bad but the Empire: good; crows: bad); then again, cats would certainly be C/conservatives. A sweet Blyton-esque read for precocious children or sentimental adults, this passed the time nicely on a long drive. It could do with a better title, though; the ducks only play a tiny role. (Favourite aside: “that beverage which humans find so comforting when things aren’t right. Tea.”) (Secondhand – Benbecula thrift shop)  I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

I read half of this large-format paperback before our trip and the rest afterward. It collects four of Hedderwick’s picture books, which are all set on the Isle of Struay, a kind of Hebridean composite that reproduces the islands’ wildlife and scenery beautifully. Katie Morag’s parents run the shop and post office and her mother always seems to be producing another little brother. In Katie Morag Delivers the Mail, the little red-haired girl causes chaos by delivering parcels at random. Sophisticated Granma Mainland and practical Grannie Island are the stars of Katie Morag and the Two Grandmothers. Katie Morag learns to deal with her anger and with being punished, respectively, in …and the Tiresome Ted and …and the Big Boy Cousins. Cute stories with useful lessons, but the illustrations are the main attraction. I’ll get the rest of the books out from the library. (Little Free Library)

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

The Florist’s Daughter by Patricia Hampl: (As featured in my

The Florist’s Daughter by Patricia Hampl: (As featured in my

A Certain Loneliness: A Memoir by Sandra Gail Lambert: (A proof copy passed on by an online book reviewing friend.) A memoir in 29 essays about living with the effects of severe polio. Most of the pieces were previously published in literary magazines. While not all are specifically about the author’s disability, the challenges of life in a wheelchair seep in whether she’s writing about managing a feminist bookstore or going on camping and kayaking adventures in Florida’s swamps. I was reminded at times of Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson.

A Certain Loneliness: A Memoir by Sandra Gail Lambert: (A proof copy passed on by an online book reviewing friend.) A memoir in 29 essays about living with the effects of severe polio. Most of the pieces were previously published in literary magazines. While not all are specifically about the author’s disability, the challenges of life in a wheelchair seep in whether she’s writing about managing a feminist bookstore or going on camping and kayaking adventures in Florida’s swamps. I was reminded at times of Constellations by Sinéad Gleeson.  No Happy Endings: A Memoir by Nora McInerny: (Borrowed from my sister.) I didn’t appreciate this as much as the author’s first memoir,

No Happy Endings: A Memoir by Nora McInerny: (Borrowed from my sister.) I didn’t appreciate this as much as the author’s first memoir,  Native Guard by Natasha Trethewey: (Free from 2nd & Charles.) Trethewey writes beautifully disciplined verse about her mixed-race upbringing in Mississippi, her mother’s death and the South’s legacy of racial injustice. She occasionally rhymes, but more often employs forms that involve repeated lines or words. The title sequence concerns a black Civil War regiment in Louisiana. Two favorites from this Pulitzer-winning collection by a former U.S. poet laureate were “Letter” and “Miscegenation”; stand-out passages include “In my dream, / the ghost of history lies down beside me, // rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm” (from “Pilgrimage”) and “I return / to Mississippi, state that made a crime // of me — mulatto, half-breed” (from “South”).

Native Guard by Natasha Trethewey: (Free from 2nd & Charles.) Trethewey writes beautifully disciplined verse about her mixed-race upbringing in Mississippi, her mother’s death and the South’s legacy of racial injustice. She occasionally rhymes, but more often employs forms that involve repeated lines or words. The title sequence concerns a black Civil War regiment in Louisiana. Two favorites from this Pulitzer-winning collection by a former U.S. poet laureate were “Letter” and “Miscegenation”; stand-out passages include “In my dream, / the ghost of history lies down beside me, // rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm” (from “Pilgrimage”) and “I return / to Mississippi, state that made a crime // of me — mulatto, half-breed” (from “South”).  I also read the first half or more of: The Music Shop by Rachel Joyce, my June book club book; Hungry by Jeff Gordinier, a journalist’s travelogue of his foodie journeys with René Redzepi of Noma fame, coming out in July; and the brand-new novel In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow – these last two are for upcoming BookBrowse reviews.

I also read the first half or more of: The Music Shop by Rachel Joyce, my June book club book; Hungry by Jeff Gordinier, a journalist’s travelogue of his foodie journeys with René Redzepi of Noma fame, coming out in July; and the brand-new novel In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow – these last two are for upcoming BookBrowse reviews.