Four February Releases: Napolitano, Offill, Smyth, Sprackland

Much as I’d like to review books in advance of their release dates, that doesn’t seem to be how things are going this year. I hope readers will find it useful to learn about recent releases they might have missed. This month I’m featuring a post-plane crash scenario, a reflection on modern anxieties, an essay about the human–birds relationship, and a meditation on graveyards.

Dear Edward by Ann Napolitano

(Published by Penguin/Viking on the 20th; came out in USA from Dial Press last month)

June 2013: a plane leaves Newark Airport for Los Angeles, carrying 192 passengers. Five hours after takeoff, it crashes in the flatlands of northern Colorado, a victim to stormy weather and pilot error. Only 12-year-old Edward Adler is found alive in the wreckage. In alternating storylines, Napolitano follows a select set of passengers (the relocating Adler family, an ailing tycoon, a Wall Street playboy, an Afghanistan veteran, a Filipina clairvoyant, a pregnant woman visiting her boyfriend) in their final hours, probing their backstories to give their soon-to-end lives context (and meaning?), and traces the first six years of the crash’s aftermath for Edward.

June 2013: a plane leaves Newark Airport for Los Angeles, carrying 192 passengers. Five hours after takeoff, it crashes in the flatlands of northern Colorado, a victim to stormy weather and pilot error. Only 12-year-old Edward Adler is found alive in the wreckage. In alternating storylines, Napolitano follows a select set of passengers (the relocating Adler family, an ailing tycoon, a Wall Street playboy, an Afghanistan veteran, a Filipina clairvoyant, a pregnant woman visiting her boyfriend) in their final hours, probing their backstories to give their soon-to-end lives context (and meaning?), and traces the first six years of the crash’s aftermath for Edward.

While this is an expansive and compassionate novel that takes seriously the effects of trauma and the difficulty of accepting random suffering, I found that I dreaded returning to the plane every other chapter – I have to take regular long-haul flights to see my family, and while I don’t fear flying, I also don’t need anything that elicits catastrophist thinking. I would read something else by Napolitano (she’s written a novel about Flannery O’Connor, for instance), but I can’t imagine ever wanting to open this up again.

I picked up a proof copy at a Penguin Influencers event.

Weather by Jenny Offill

(Published by Knopf [USA] on the 11th and Granta [UK] on the 13th)

Could there be a more perfect book for 2020? A blunt, unromanticized but wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, Weather is written in the same aphoristic style as Offill’s Dept. of Speculation but has a more substantial story to tell. Lizzie Benson is married with a young son and works in a New York City university library. She takes on an informal second job as PA to Sylvia, her former professor, who runs a podcast on environmental issues and travels to speaking engagements.

Could there be a more perfect book for 2020? A blunt, unromanticized but wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, Weather is written in the same aphoristic style as Offill’s Dept. of Speculation but has a more substantial story to tell. Lizzie Benson is married with a young son and works in a New York City university library. She takes on an informal second job as PA to Sylvia, her former professor, who runs a podcast on environmental issues and travels to speaking engagements.

Set either side of Trump’s election, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom, from environmentalists to Bible-thumpers (like Lizzie’s mother) to those who aren’t sure they’ll even make it past tomorrow (like her brother, a highly unstable ex-addict who’s having a baby with his girlfriend). It’s a wonder it doesn’t end up feeling depressing. Lizzie’s sardonic narration is an ideal way of capturing relatable feelings of anger and helplessness, cringing fear and desperate hope. Don’t expect to come away with your worries soothed, though there is some comfort to be found in the feeling that we’re all in this together.

Favorite lines:

“Young person worry: What if nothing I do matters? Old person worry: What if everything I do does?”

“Once sadness was considered one of the deadly sins, but this was later changed to sloth. (Two strikes then.)”

“My husband is reading the Stoics before breakfast. That can’t be good, can it?”

I read an e-ARC via Edelweiss.

An Indifference of Birds by Richard Smyth

(Published by Uniformbooks on the 14th)

Birds have witnessed the whole of human history, sometimes profiting from our behavior – our waste products provide them with food, our buildings can be handy nesting and hunting platforms, and our unintentional wastelands and demilitarized zones turn into nature reserves – but more often suffering incidental damage. That’s not even considering our misguided species introductions and the extinctions we’ve precipitated. Eighty percent of bird species are now endangered. For as minimal as the human fossil record will be, we have a lot to answer for.

Birds have witnessed the whole of human history, sometimes profiting from our behavior – our waste products provide them with food, our buildings can be handy nesting and hunting platforms, and our unintentional wastelands and demilitarized zones turn into nature reserves – but more often suffering incidental damage. That’s not even considering our misguided species introductions and the extinctions we’ve precipitated. Eighty percent of bird species are now endangered. For as minimal as the human fossil record will be, we have a lot to answer for.

From past to future, archaeology to reintroduction and de-extinction projects, this is a wide-ranging essay that still comes in at under 100 pages. It’s a valuable shift in perspective from human-centric to bird’s-eye view. The prose is not at all what I’ve come to expect from nature writing (earnest, deliberately lyrical); it’s more rhetorical and inventive, a bit arch but still passionate – David Foster Wallace meets Virginia Woolf? The last six paragraphs, especially, soar into sublimity. A niche book, but definitely recommended for bird-lovers.

Favorite lines:

“They must see us, watch us, from the same calculating perspective as they did two million years ago. We’re still galumphing heavy-footed through the edgelands, causing havoc, small life scattering wherever we tread.”

“Wild things lease these places from a capricious landlord. They’re yours, we say, until we need them back.”

I pre-ordered my copy directly from the publisher.

These Silent Mansions: A life in graveyards by Jean Sprackland

(Published by Jonathan Cape on the 6th)

I’m a big fan of Sprackland’s beachcombing memoir, Strands, and have also read some of her poetry. Familiarity with her previous work plus a love for graveyards induced me to request a copy of her new book. In it she returns to the towns and cities she has known, wanders through their graveyards, and researches and imagines her way into the stories of the dead. For instance, she finds the secret burial place of persecuted Catholics in Lancashire, learns about a wrecked slave ship in a Devon cove, and laments two dead children whose bodies were sold for dissections in 1890s Oxford. She also remarks on the shifts in her own life, including the fact that she now attends more funerals than weddings, and the displacement involved in cremation – there is no site she can visit to commune with her late mother.

I’m a big fan of Sprackland’s beachcombing memoir, Strands, and have also read some of her poetry. Familiarity with her previous work plus a love for graveyards induced me to request a copy of her new book. In it she returns to the towns and cities she has known, wanders through their graveyards, and researches and imagines her way into the stories of the dead. For instance, she finds the secret burial place of persecuted Catholics in Lancashire, learns about a wrecked slave ship in a Devon cove, and laments two dead children whose bodies were sold for dissections in 1890s Oxford. She also remarks on the shifts in her own life, including the fact that she now attends more funerals than weddings, and the displacement involved in cremation – there is no site she can visit to commune with her late mother.

I most enjoyed the book’s general observations: granite is the most prized headstone material, most graves go unvisited after 15 years, and a third of Britons believe in angels despite the country’s overall decline in religious belief. I also liked Sprackland’s list of graveyard charms she has seen. While I applaud any book that aims to get people thinking and talking about death, I got rather lost in the historical particulars of this one.

Favorite lines:

“This is the paradox at the heart of our human efforts to remember and memorialise: the wish to last forever, and the knowledge that we are doomed to fail.”

“Life, under such a conscious effort of remembering, sometimes resembles a series of clumsy jump-cuts rather than one continuous narrative.”

My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Childless Voices by Lorna Gibb

People end up not having children for any number of reasons: medical issues, bereavement, a lack of finances, not having a partner at the right time, or the simple decision not to become a parent. The subtitle of Lorna Gibb’s Childless Voices acknowledges these various routes: “Stories of Longing, Loss, Resistance and Choice.”

For Gibb, a university lecturer, biographer and novelist, the childless state was involuntary, a result of severe endometriosis that led to infertility and early menopause. Although this has been a source of sadness for her and her husband, she knows that she has it easy compared to women in other parts of the world. Through her research and Skype interviews, she hears horrific stories about infertile women who meet with domestic violence and social ostracism and are sometimes driven to suicide. In Ghana childless women can be branded as witches and exiled. Meanwhile, some are never given the chance to have the children they might long for: Gibb cites China’s one-child policy, female genital mutilation, and enforced sterilization programs like those of the Roma in Yugoslavia and the Quechua in Peru.

For Gibb, a university lecturer, biographer and novelist, the childless state was involuntary, a result of severe endometriosis that led to infertility and early menopause. Although this has been a source of sadness for her and her husband, she knows that she has it easy compared to women in other parts of the world. Through her research and Skype interviews, she hears horrific stories about infertile women who meet with domestic violence and social ostracism and are sometimes driven to suicide. In Ghana childless women can be branded as witches and exiled. Meanwhile, some are never given the chance to have the children they might long for: Gibb cites China’s one-child policy, female genital mutilation, and enforced sterilization programs like those of the Roma in Yugoslavia and the Quechua in Peru.

Gibb is admirably comprehensive here, considering every possible aspect of childlessness. Particularly interesting are the different cultural adaptations childless women make. Certain countries allow polygamy, giving a second wife a chance to bear children on behalf of an infertile one; Kenya and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa recognize ‘marriages’ between childless women so they can create a family and support system. In Albania being a “sworn virgin” is an old and venerable custom. And, of course, there are any number of support groups and online communities. The situation of those who were once parents but are no longer is especially wrenching. Stillbirth only started to be talked about in the 1980s, Gibb notes, but even today is seen as a lesser loss than that of a child who dies later in life.

The author believes there is societal injustice in terms of who has access to fertility treatment and how the state deals with childless people. In the UK, she characterizes IVF as a “postcode lottery”: where you live often determines how many free cycles you’re entitled to on the NHS. In the USA, meanwhile, fertility treatment is so expensive that only those with a certain level of wealth can consider it. The childless may also feel ‘punished’ by tax breaks that favor parents and workplaces that expect non-parents to work unsociable hours. In a sense, then, the childless contribute more but benefit less.

Chosen childlessness is perhaps given short shrift at just 32 pages out of 239. However, it’s still a very thorough treatment of the reasons why couples decide not to become parents, including cultural norms, career goals, self-knowledge and environmental concerns. No surprise that this was the chapter that resonated with me the most. I also especially enjoyed the personal interludes (all titled “A Short Note on…”) in which Gibb celebrates her feminist, childless heroes like Frida Kahlo and Anaïs Nin and writes about how much becoming a godmother meant to her but also of the sadness of seeing a good friend’s teenage son die of a brain tumor.

By coincidence, I’ve recently read another book on the same topic: Do You Have Kids? Life when the Answer Is No, by Kate Kaufmann (coming out in America next month). Gibb primarily traces the many different reasons for childlessness; Kaufmann mostly addresses the question of “now what?” – how women without children approach careers, wider family life, housing options, spirituality and the notion of leaving a legacy. Gibb’s approach is international and comparative, while Kaufmann’s is largely specific to the USA. Though the two authors are childless due to endometriosis and infertility, they feel sisterhood with women who never became mothers for whatever reason. I’d say these two books are complementary rather than rivals, and reveal valuable perspectives that can sometimes be overlooked.

By coincidence, I’ve recently read another book on the same topic: Do You Have Kids? Life when the Answer Is No, by Kate Kaufmann (coming out in America next month). Gibb primarily traces the many different reasons for childlessness; Kaufmann mostly addresses the question of “now what?” – how women without children approach careers, wider family life, housing options, spirituality and the notion of leaving a legacy. Gibb’s approach is international and comparative, while Kaufmann’s is largely specific to the USA. Though the two authors are childless due to endometriosis and infertility, they feel sisterhood with women who never became mothers for whatever reason. I’d say these two books are complementary rather than rivals, and reveal valuable perspectives that can sometimes be overlooked.

My rating:

Childless Voices was published by Granta on February 7th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Wise Children by Angela Carter: On the Page and on the Stage

“What a joy it is to dance and sing!”

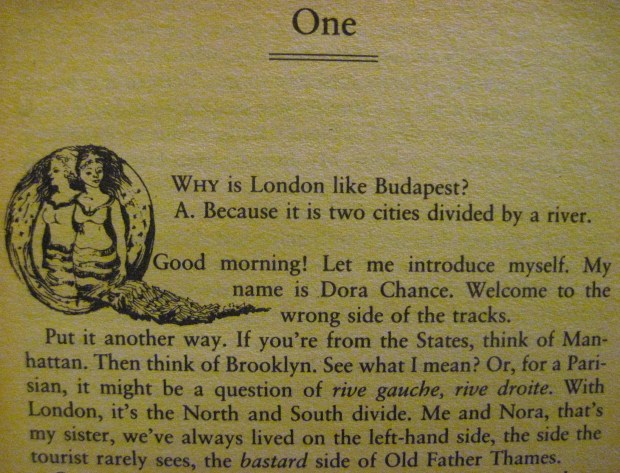

Through a Granta giveaway on Twitter I won two tickets to see Wise Children at London’s Old Vic theatre on October 18th. Clare of A Little Blog of Books joined me for an excellent evening at the theatre, and we both followed it up by reading the novel – Angela Carter’s final book, published in 1991. (Clare’s write-up of the book and play is here.) It has one of the best openers I’ve come across recently:

Twins Nora and Dora Chance turn 75 today; their father, Shakespearean actor Melchior Hazard, who has never publicly acknowledged them because they were born out of wedlock to a servant girl who died in childbirth, turns 100. At the last minute an invitation to his birthday party arrives, and between this point and the party Dora fills us in on the sisters’ knotty family history. Their father is also a twin (though fraternal); his brother Peregrine was more of a father to them than Melchior, with “Grandma” Chance, the owner of the boarding house where they were born, the closest thing they had to a mother growing up. By the time they’re teenagers, the girls are on stage at music halls. After a jaunt to Hollywood to appear in Melchior’s filming of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, they’re back in time for wartime deprivation and tragedy in South London, and decades of shabby nostalgia follow.

It’s a big, bawdy story that has, amazingly, been compressed into just 230 pages. There are five sets of twins in total, with multiple cases of doubling, incest and mistaken identity that would make Shakespeare proud. The novel is composed of five long chapters, like the acts in a play, with a Dramatis Personae on the last two pages (though it might have proven more helpful at the start), and the sisters even live at 49 Bard Road. Dora’s voice is slang-filled and gossipy, and she dutifully presents the sisters’ past as the tragicomedy that it was.

Indeed, Wise Children seems perfect for the stage, and Emma Rice’s production recreates everything that’s best about the book, including Dora’s delightful narration. At the start, resplendent in kimonos and turbans, she and Nora greet us from their Brixton home – represented by a kitschy caravan, which with minor redecoration between scenes serves for all the play’s interiors. The 75-year-olds remain on stage for virtually the entire performance, watching along with the audience from the wings and adding in fragments of commentary, often drawn directly from the text, as scenes from their past unfold (including plenty of simulated sex – I wouldn’t recommend taking along any under-15s).

Androgynous extras cycle into various roles as the action proceeds, with the twins represented first by puppets, then by three sets of actors of various races and genders – the teenage/young adult Nora is played by a Black man, while 75-year-old Dora is a man perhaps of South Asian extraction. This adds extra irony to the humor of one of Nora’s lines: “It’s every woman’s tragedy that, after a certain age, she looks like a female impersonator.” Grandma Chance, with her beehive, cat-eye glasses and nude bodysuit, steals the show, with seaside comedian Gorgeous George coming a close second as the most entertaining character.

The play has cut out most of the 1980s layer of characters and made the story line stronger in doing so. The only other scene I wish could have been included is a farcical multiple wedding ceremony in Hollywood. The glitzy costumes, recurring butterflies, and John Waters-esque tacky-chic of the set all felt true to the atmosphere of the book, and the songs mentioned in the text (such as “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love, Baby”) are supplemented by a couple of numbers that evoke the 1980s setting: “Electric Avenue” and “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.”

This was my fifth book by Carter, and now a joint favorite with The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories – but I liked the play that little bit better. If you get a chance to see it in London or on tour further afield, don’t pass it up. It’s a pure joy.

This was my fifth book by Carter, and now a joint favorite with The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories – but I liked the play that little bit better. If you get a chance to see it in London or on tour further afield, don’t pass it up. It’s a pure joy.

My rating: Book ; Play

; Play

To compare the thoughts of some professional theatregoers and see a few photos, check out the reviews on the Guardian and Telegraph websites.

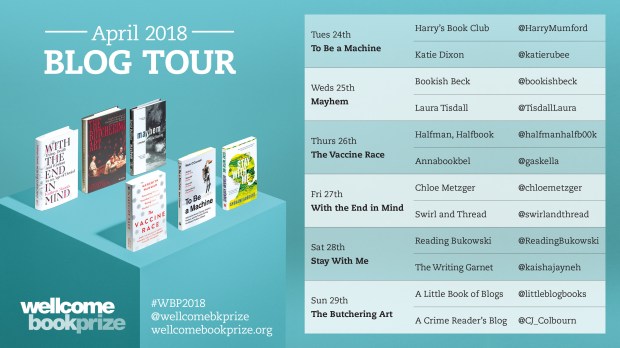

The Wellcome Book Prize 2018 Awards Ceremony

Hey, we got it right! Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine, our shadow panel’s pick, won the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 last night. Of the three shadow panels I’ve participated in and the many others I’ve observed, this is the only time I remember the shadow winner matching the official one. Clare, Paul and I were there in person for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. When we briefly spoke to the judges’ chair, Edmund de Waal, later in the evening, he said he was “relieved” that their decision matched ours – but I think it was definitely the other way around!

Hey, we got it right! Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine, our shadow panel’s pick, won the Wellcome Book Prize 2018 last night. Of the three shadow panels I’ve participated in and the many others I’ve observed, this is the only time I remember the shadow winner matching the official one. Clare, Paul and I were there in person for the announcement at the Wellcome Collection in London. When we briefly spoke to the judges’ chair, Edmund de Waal, later in the evening, he said he was “relieved” that their decision matched ours – but I think it was definitely the other way around!

Simon Chaplin, Director of Culture & Society at the Wellcome Trust, said that each year more and more books are being considered for the prize. De Waal revealed that the judges read 169 books over nine months in what was for him his most frightening book club ever. “To bring the worlds of medicine and health into urgent conversation” requires a “lyrical and disciplined choreography,” he said, and “how we shape stories of science … is crucial.” He characterized the judges’ discussions as both “personal and passionate.” The Wellcome-shortlisted books make a space for public debate, he insisted.

Judges Gordon, Paul-Choudhury, Critchlow, Ratcliffe and de Waal. Photo by Clare Rowland.

The judges brought each of the five authors present onto the stage one at a time for recognition. De Waal praised Ayobami Adebayo’s “narrative of hope and fear and anxiety” and Meredith Wadman’s “beautifully researched and paced thriller.” Dr Hannah Critchlow of Magdalene College, Cambridge called Lindsey Fitzharris’s The Butchering Art “gruesome yet fascinating.” Oxford English professor Sophie Ratcliffe applauded Kathryn Mannix’s book and its mission. New Scientist editor-in-chief Sumit Paul-Choudhury said Mark O’Connell’s book is about the future “just as much as what it means to be human in the twenty-first century.” Journalist and mental health campaigner Bryony Gordon thanked Sigrid Rausing for her “great honesty and stunning prose.”

But there can only be one winner, and it was Mark O’Connell, who couldn’t be there as his wife is/was giving birth to their second child imminently. The general feeling in the room was that he’d made the right call by deciding to stay with his family. He must be feeling like the luckiest man on earth right now, to have a baby plus £30,000! Max Porter, O’Connell’s editor at Granta and the author of Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, received the award on his behalf and read out the extremely witty speech he’d written in advance.

Afterwards we spoke to three of the shortlisted authors. Kathryn Mannix said she’d so enjoyed following our shadow panel reviews and that it was for the best that O’Connell won, as any other outcome might have spoiled the lovely girls’ club the others had going on during the weekend’s events. I got two signatures and we nabbed a quick photo with Lindsey Fitzharris. It was also great to meet Simon Savidge, the king of U.K. book blogging, and author and vlogger Jen Campbell. Other ‘celebrities’ spotted: Sarah Bakewell and Ben Goldacre.

This time I stayed long enough for pudding canapés to come around – raspberry cake pops and mini meringues with strawberries. What a great idea! On the way out I again acquired a Wellcome goody bag: this year’s tote with a copy of The Butchering Art, which I only had on Kindle before. I’d also treated myself to this brainy necklace from the Wellcome shop and wore it to the ceremony. An all-round great evening. I’m looking forward to next year’s prize season already!

Paul, Lindsey Fitzharris, Clare and me.

Wellcome Book Prize Blog Tour: Sigrid Rausing’s Mayhem

“Now that it’s all over I find myself thinking about family history and family memories; the stories that hold a family together and the acts that can split it apart.”

Sigrid Rausing’s brother, Hans, and his wife, Eva, were wealthy philanthropists – and drug addicts who kept it together long enough to marry and have children before relapsing. Hans survived that decade-long dive back into addiction, but Eva did not: in July 2012 the 48-year-old’s decomposed body was found in a sealed-off area of the couple’s £70 million Chelsea mansion. The postmortem revealed that she had been using cocaine, which threw her already damaged heart into a chaotic rhythm. She’d been dead in their drug den for over two months.

Those are the bare facts. Scandalous enough for you? But Mayhem is no true crime tell-all. It does incorporate the straightforward information that is in the public record – headlines, statements and appearances – but blends them into a fragmentary, dreamlike family memoir that proceeds through free association and obsessively deliberates about the nature and nurture aspects of addictive personalities. “We didn’t understand that every addiction case is the same dismal story,” she writes, in a reversal of Tolstoy’s maxim about unhappy families.

Rausing’s memories of idyllic childhood summers in Sweden reminded me of Tove Jansson stories, and the incessant self-questioning of a family member wracked by remorse is similar to what I’ve encountered in memoirs and novels about suicide in the family, such as Jill Bialosky’s History of a Suicide and Miriam Toews’ All My Puny Sorrows. Despite all the pleading letters and e-mails she sent Hans and Eva, and all the interventions and rehab spells she helped arrange, Rausing has a nagging “sense that when I tried I didn’t try hard enough.”

The book moves sinuously between past and present, before and after, fact and supposition. There are a lot of peculiar details and connections in this story, starting with the family history of dementia and alcoholism. Rausing’s grandfather founded the Tetra Pak packaging company, later run by her father. Eva had a pet conspiracy theory that her father-in-law murdered Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme in 1986.

Rausing did anthropology fieldwork in Estonia and is now the publisher of Granta Books and Granta magazine. True to her career in editing, she’s treated this book project like a wild saga that had to be tamed, “all the sad and sordid details redacted,” but “I fear I have redacted too much,” she admits towards the end. She’s constantly pushing back against the more sensational aspects of this story, seeking instead to ground it in family experience. The book’s sketchy nature is in a sense necessary because information about her four nieces and nephews, of whom she took custody in 2007, cannot legally be revealed. But if she’d waited until they were all of age, might this have been a rather different memoir?

Mayhem effectively conveys the regret and guilt that plague families of addicts. It invites you to feel what it is really like to live through the “years of failed hope” that characterize this type of family tragedy. It doesn’t offer any easy lessons seen in hindsight. That makes it an uncomfortable read, but an honest one.

With thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review.

My gut feeling: This book’s style could put off more readers than it attracts. I can think of two other memoirs from the longlist that I would have preferred to see in this spot. I suppose I see why the judges rate Mayhem so highly – Edmund de Waal, the chair of this year’s judging panel, describes the Wellcome shortlist as “books that start debates or deepen them, that move us profoundly, surprise and delight and perplex us” – but it’s not in my top tier.

See what the rest of the shadow panel has to say about this book:

Annabel’s review: “Rausing is clearly a perceptive writer. She is very hard on herself; she is brutally honest, knowing that others will be hurt by the book.”

Clare’s review: “Rausing writes thoughtfully about the nature of addiction and its many contradictions.”

Laura’s review: “One of the saddest bits of Mayhem is when Rausing simply lists some of the press headlines that deal with her family story in reverse order, illustrating the seemingly inescapable spiral of addiction.”

Paul’s review: “It is not an easy read subject wise, thankfully Rausing’s sparse but beautiful writing helps makes this an essential read.”

Also, be sure to visit Laura’s blog today for an exclusive extract from Mayhem.

Shortlist strategy: Tomorrow I’ll post a quick response to Meredith Wadman’s The Vaccine Race.

If you are within striking distance of London, please consider coming to one of the shortlist events being held this Saturday and Sunday.

I was delighted to be asked to participate in the Wellcome Book Prize blog tour. See below for details of where other reviews and extracts have appeared or will be appearing soon.

Better Late than Never: The Nix by Nathan Hill

I was wary of Nathan Hill’s debut novel, The Nix, as I always am of big ol’ books. Six hundred and twenty pages of small print: was it going to be worth it? Luckily, the answer was a resounding yes. If you’ve loved The World According to Garp, City on Fire, The Goldfinch, and/or Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist, you should pick this one up right away. From the first few pages onwards, I was impressed by Hill’s carefully honed sentences. He mixes up the paragraph arrangement in a particularly effective way, such that long thoughts are punctuated by a killer one-liner given a paragraph of its own. Here’s one: “How easily a simple façade can become your life, can become the truth of your life.”

In 2011 Samuel Anderson and his estranged mother, Faye, find themselves in strange situations. Samuel is an assistant English professor at a small suburban Chicago college. Once the Next Big Thing, feted by Granta for a brilliant short story, he has never delivered his contracted novel and spends more time in the World of Elfscape online game than he does engaging in real life. Now Laura Pottsdam, a student he caught plagiarizing a Hamlet essay, is on a mission to take Samuel down. Meanwhile Faye is awaiting trial for throwing rocks at Governor Packer, a conservative presidential hopeful from Wyoming. It’s been 23 years since Faye walked out on Samuel and his father, but her lawyer still hopes Samuel will be willing to write a character reference to be used in her defense, prompting their awkward reunion.

This is a rich, multi-layered story about family curses and failure, and how to make amends for a life full of mistakes. Along with 2011, the two main time periods are 1968, when Faye was a would-be radical caught up in student violence; and 1988, the summer before Faye left, when Samuel met twins Bishop and Bethany Fall, two friends who would still be having an impact on his life decades later even though they moved away after a few months. Although most of the action takes place in Iowa and Chicago, there’s also a brief interlude set in Norway when Faye tries to track down the ghosts of her father’s homeland. He’d told her stories of the nisse and the Nix, a house spirit and a water spirit in the form of a giant horse: both lead greedy children to their doom, a terrifying prospect for an anxious girl like Faye.

This is a rich, multi-layered story about family curses and failure, and how to make amends for a life full of mistakes. Along with 2011, the two main time periods are 1968, when Faye was a would-be radical caught up in student violence; and 1988, the summer before Faye left, when Samuel met twins Bishop and Bethany Fall, two friends who would still be having an impact on his life decades later even though they moved away after a few months. Although most of the action takes place in Iowa and Chicago, there’s also a brief interlude set in Norway when Faye tries to track down the ghosts of her father’s homeland. He’d told her stories of the nisse and the Nix, a house spirit and a water spirit in the form of a giant horse: both lead greedy children to their doom, a terrifying prospect for an anxious girl like Faye.

Political protest is a thread running all through the novel, though it never drowns out the centrality of the mother–son relationship: the 1968 Grant Park protest Faye attends in Chicago, the anti-Iraq War march Samuel and Bethany go on in 2004, the Occupy demonstrations taking place in 2011, and Faye’s odd transformation into the Packer Attacker. Hill makes cogent comments on contemporary America, where the “pastime is no longer baseball. Now it’s sanctimony.” Young people parcel emotions into easy categories for social media, which also markets ready-made heroes (pop singer Molly Miller) and villains (Faye).

Hill is a funny and inventive writer; a few of his more virtuosic moments include an argument with headings indicating its logical fallacies, a relationship presented as a Choose Your Own Adventure story, and a nearly-eleven-page sentence in which a character has a health crisis. These sections are almost too long – Come now, you’re just showing off, I thought. But changing up the structure like that does mean that the novel is never boring, and its reflections on self-knowledge and how we get lost, stuck in patterns of our own creating, made me think deeply. This is one debut that really does live up to the hype; look out for it, and for the upcoming television adaptation directed by J.J. Abrams and starring Meryl Streep.

My rating:

First published in August 2016, The Nix was released in the UK in paperback on September 21st. My thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Madness Is Better than Defeat by Ned Beauman

I’ve been a Ned Beauman fan ever since I read his debut, Boxer, Beetle, in 2011. Born in 1985, the Londoner is now the author of four novels and was named one of Granta’s 20 best British novelists under the age of 40. His books are madcap and complex; three out of four have historical settings (all broadly in the World War II era), but this is definitely not historical fiction as we know it. If I tell you that some common elements in his work are Nazis, pharmaceuticals and gay sex, and that his first two books reminded me most of Nick Harkaway, you’ll get some idea of the niche he’s working in.

Madness Is Better than Defeat takes its title from a line in Orson Welles’s never-filmed screenplay of Heart of Darkness. We open in 1959 with Zonulet, a 43-year-old alcoholic CIA officer, writing a tell-all memoir about what happened when two parties set out to find a Mayan temple in Honduras in 1938. Sadistic business magnate Elias Coehorn, Sr. sent his feckless son, Elias Jr., to dismantle the temple and bring it back to New York City, while Arnold Spindler, chairman of Kingdom Pictures, tasked Jervis Whelt with directing a movie on location at the temple: Hearts in Darkness, a comedy about a spoiled society boy who’s sent on an archaeological dig to a Mayan temple and opens a nightclub when he gets there.

Madness Is Better than Defeat takes its title from a line in Orson Welles’s never-filmed screenplay of Heart of Darkness. We open in 1959 with Zonulet, a 43-year-old alcoholic CIA officer, writing a tell-all memoir about what happened when two parties set out to find a Mayan temple in Honduras in 1938. Sadistic business magnate Elias Coehorn, Sr. sent his feckless son, Elias Jr., to dismantle the temple and bring it back to New York City, while Arnold Spindler, chairman of Kingdom Pictures, tasked Jervis Whelt with directing a movie on location at the temple: Hearts in Darkness, a comedy about a spoiled society boy who’s sent on an archaeological dig to a Mayan temple and opens a nightclub when he gets there.

The scene is set for a clash of cultures: the New York faction bent on destruction versus the Los Angeles crew intent on creation. They’re joined by Joan Burlingame, a stuffy Cambridge anthropologist, and Leland Trimble, a gossip journalist who was formerly Zonulet’s colleague at the New York Evening Mirror. To start with the screwball plot is uncannily similar to that of Hearts in Darkness itself, and it seems the stalemate between the two groups will be mined purely for comic potential. But as the years pass and the deadlock continues, this becomes more of a psychological study of a community in isolation, rather like The Lord of the Flies or T.C. Boyle’s The Terranauts.

Alliances are formed and broken based on blackmail over the characters’ past and present indiscretions; routines and workarounds are developed (though an attempt to recreate Bloody Marys and Eggs Benedict fails); soon a whole new generation is being raised with little knowledge of what’s happened outside this jungle for more than a decade; all they have to go on is false information about the outcome of World War II conveyed by an ex-Nazi.

They spoke in American accents and they had all been taught a sort of eschatology in which they would one day return with their parents to Hollywood or New York. But they belonged to the rainforest and to the temple. And the geometry of the latter … was so primal to them that any talk of disassembly or reassembly struck them as abstract, almost paradoxical.

One of the hardest things to believe about the story line – so you’ll simply have to suspend your disbelief – is that no one was overly concerned when these two groups failed to reappear after assignments that were meant to last only a matter of weeks. Not until Zonulet gets to Honduras in 1956 to learn more about a secret CIA guerrilla training camp in the area is there sustained interest in what became of these exiled Americans, and it’s another two years before their jungle idyll comes to an explosive end.

What we have here is a twist on the Mummy’s Curse trope, with the temple causing many to lose their minds or their lives. I wish the novel could have retained its initial screwball charm without going quite so dark and strange, but that’s Beauman for you. I also thought that this was a good 100–150 pages too long, with many more secondary characters, subplots and asides than necessary. Ironically, even after nearly 500 pages, its conclusion left me wondering about some loose ends. But the writing is consistently amusing, particularly the voices captured in letters or diaries and the wacky metaphors:

- “The sky in the west was mixing an Old-Fashioned”

- “All her blood had thickened in her head like the last of the catsup”

- “They were so slathered in mulch that their two bodies together might have been some octopod newly burped from a mudpot.”

- “To describe the truck as temperamental would have been condescending; rather, I had the impression it had been earnestly wrestling with a deep crisis of personal faith about the very principle of internal combustion as a motive power.”

If you’re new to Ned Beauman, I’d suggest starting with The Teleportation Accident, my favorite of his novels. From there you could move on to Boxer, Beetle or Glow; this one can wait until you’re a confirmed admirer.

My rating:

Madness Is Better than Defeat is published in the UK today, August 24th, by Sceptre and will be available in the USA in February. With thanks to Ruby Mitchell for the free review copy.

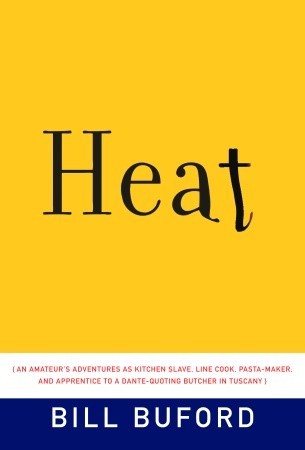

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.”

Mario Batali is the book’s presiding imp. In 2002–3, Buford was an unpaid intern in the kitchen of Batali’s famous New York City restaurant, Babbo, which serves fancy versions of authentic Italian dishes. It took 18 months for him to get so much as a thank-you. Buford’s strategy was “be invisible, be useful, and eventually you’ll be given a chance to do more.” I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list.

I was delighted to learn that this year Buford released a sequel of sorts, this one about French cuisine: Dirt. It’s on my wish list. Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

Along with an agricultural center, the American Baptist missionaries were closely associated with a hospital, Hôpital le Bon Samaritain, run by amateur archaeologist Dr. Hodges and his family. Although Apricot and her two younger sisters were young enough to adapt easily to life in a developing country, they were disoriented each time the family returned to California in between assignments. Their bonds were shaky due to her father’s temper, her parents’ rocky relationship, and the jealousy provoked over almost adopting a Haitian baby girl.

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol Oates (oats!)

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Of course, not all of my selections were explicitly food-related; others simply had food words in their titles (or, as above, in the author’s name). Of these, my favorite was a reread,

Two other favorites were “Touching People,” in which a sixty-something woman takes a honeymooning couple to see her ex-husband’s grave, and “Small Differences,” about a woman who’s cat-sitting for her on-and-off boyfriend and remembers the place faith used to have in her life. Both dramatize the divide between youth and age; in the latter the cat is named Echo, a reminder that the past still resonates. Another standout is “Learning,” about a painting teacher with a crumbling house and marriage whose deadbeat college friend has become a parenting guru. (This one reminded me of Curtis Sittenfeld’s “The Prairie Wife.”)

Two other favorites were “Touching People,” in which a sixty-something woman takes a honeymooning couple to see her ex-husband’s grave, and “Small Differences,” about a woman who’s cat-sitting for her on-and-off boyfriend and remembers the place faith used to have in her life. Both dramatize the divide between youth and age; in the latter the cat is named Echo, a reminder that the past still resonates. Another standout is “Learning,” about a painting teacher with a crumbling house and marriage whose deadbeat college friend has become a parenting guru. (This one reminded me of Curtis Sittenfeld’s “The Prairie Wife.”)

A decade ago, Barbara Ehrenreich discovered a startling paradox through a Scientific American article: the immune system assists the growth and spread of tumors, including in breast cancer, which she had in 2000. It was an epiphany for her, confirming that no matter how hard we try with diet, exercise and early diagnosis, there’s only so much we can do to preserve our health; “not everything is potentially within our control, not even our own bodies and minds.” I love Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die (alternate title: Bright-Sided), which is what I call an anti-self-help book refuting the supposed health benefits of positive thinking. In that book I felt like her skeptical approach was fully warranted, and I could sympathize with her frustration – nay, outrage – when people tried to suggest she’d attracted her cancer and limited her chances of survival through her pessimism.

A decade ago, Barbara Ehrenreich discovered a startling paradox through a Scientific American article: the immune system assists the growth and spread of tumors, including in breast cancer, which she had in 2000. It was an epiphany for her, confirming that no matter how hard we try with diet, exercise and early diagnosis, there’s only so much we can do to preserve our health; “not everything is potentially within our control, not even our own bodies and minds.” I love Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die (alternate title: Bright-Sided), which is what I call an anti-self-help book refuting the supposed health benefits of positive thinking. In that book I felt like her skeptical approach was fully warranted, and I could sympathize with her frustration – nay, outrage – when people tried to suggest she’d attracted her cancer and limited her chances of survival through her pessimism.

Lents is a biology professor at John Jay College, City University of New York, and in this, his second book, he explores the ways in which the human body is flawed. These errors come in three categories: adaptations to the way the world was for early humans (to take advantage of once-scarce nutrients, we gain weight quickly – but lose it only with difficulty); incomplete adaptations (our knees are still not fit for upright walking); and the basic limitations of our evolution (inefficient systems such as the throat handling both breath and food, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve being three times longer than necessary because it loops around the aorta). Consider that myopia rates are 30% or higher, the retina faces backward, sinuses drain upwards, there are 100+ autoimmune diseases, we have redundant bones in our wrist and ankle, and we can’t produce most of the vitamins we need. Put simply, we’re not a designer’s ideal. And yet this all makes a lot of sense for an evolved species.

Lents is a biology professor at John Jay College, City University of New York, and in this, his second book, he explores the ways in which the human body is flawed. These errors come in three categories: adaptations to the way the world was for early humans (to take advantage of once-scarce nutrients, we gain weight quickly – but lose it only with difficulty); incomplete adaptations (our knees are still not fit for upright walking); and the basic limitations of our evolution (inefficient systems such as the throat handling both breath and food, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve being three times longer than necessary because it loops around the aorta). Consider that myopia rates are 30% or higher, the retina faces backward, sinuses drain upwards, there are 100+ autoimmune diseases, we have redundant bones in our wrist and ankle, and we can’t produce most of the vitamins we need. Put simply, we’re not a designer’s ideal. And yet this all makes a lot of sense for an evolved species.