The Booker Prize 2023 Ceremony

Yesterday evening Eleanor Franzen of Elle Thinks and I had the enormous pleasure of attending the Booker Prize awards ceremony at Old Billingsgate in London. I won tickets through “The Booker Prize Book Club” Facebook group, which launched just 10 or so weeks ago but has already garnered over 6000 members from around the world. They ran a competition for shortlist book reviews and probably did not attract nearly as many entries as they expected to. This probably worked to my advantage, but as it’s the only prize I can recall winning for my writing, I am going to take it as a compliment nonetheless! I submitted versions of my reviews of If I Survive You and Western Lane – the only shortlistees that I’ve read – and it was the latter that won us tickets.

We arrived at the venue 15 minutes before the doors opened, sheltering from the drizzle under an overhang and keeping a keen eye on arrivals (Paul Lynch and sodden Giller Prize winner Sarah Bernstein, her partner wearing both a kilt and their several-week-old baby). Elle has a gift for small talk and we had a nice little chat with Jonathan Escoffery and his 4th Estate publicist before they were whisked inside. His head was spinning from the events of the week, including being part of a Booker delegation that met Queen Camilla.

There was a glitzy atmosphere, with a photographer-surrounded red carpet and large banners for each shortlisted novel along the opposite wall, plus an exhibit of the hand-bound editions created for each book. We enjoyed some glasses of champagne and canapés (the haddock tart was the winner) and collared Eric Karl Anderson of Lonesome Reader. It was lovely to catch up with him and Eleanor and do plenty of literary celebrity spotting: Graeme Macrae Burnet, Eleanor Catton, judge Mary Jean Chan, Natalie Haynes, Alan Hollinghurst, Anna James, Jean McNeil, Johanna Thomas-Corr (literary editor of the Sunday Times) and Sarah Waters. Later we were also able to chat with Julianne Pachico, our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel winner from 2017. She has recently gotten married and released her third novel.

We were allocated to Table 11 in the front right corner. Also at our table were some Booker Prize editorial staff members, the other competition winner (for a video review) and her guest, an Instagram influencer, a Reading Agency employee, and several more people. The three-course dinner was of a very high standard for mass catering and the wine flowed generously. I thoroughly enjoyed my meal. Afterward we had a bit of time for taking red carpet photos and one of Eleanor with the banner for our predicted winner, Prophet Song.

Some of you may have watched the YouTube livestream, or listened to the Radio 4 live broadcast. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s speech was a highlight. She spoke about the secret library at the Iranian prison where she was held for six years. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (there was a long waiting list among the prisoners and wardens, she said), and especially The Return by Hisham Matar meant a lot to her. From earlier on in the evening, I also enjoyed judge Adjoa Andoh’s dramatic reading of an excerpt from Possession in honour of the late Booker winner A.S. Byatt, and Shehan Karunatilaka’s tongue-in-cheek reflections on winning the Booker – he warned the next winner that they won’t write a word for a whole year.

There was a real variety of opinion in the room as to who would win. Earlier in the evening we’d spoken to people who favoured Western Lane, This Other Eden and The Bee Sting. But both Elle and I were convinced that Prophet Song would take home the trophy, and so it did. Despite his genuine display of shock, Paul Lynch was well prepared with an excellent speech in which he cited the apocrypha and Albert Camus. In a rapid-fire interview with host Samira Ahmed, he added that he can still remember sitting down and weeping after finishing The Mayor of Casterbridge, age 15 or 16, and hopes that his work might elicit similar emotion. I’m not sure that I plan on reading it myself, but from what I’ve heard it’s a powerfully convincing dystopian novel that brings political and social collapse home in a realistic way.

All in all, a great experience for which I am very grateful! (Thanks to Eleanor for all the photos.)

Have you read Prophet Song? Did you expect it to win the Booker Prize?

Recent Literary Awards & Online Events: Folio Prize and Claire Fuller

Literary prize season is in full swing! The Women’s Prize longlist, revealed on the 10th, contained its usual mixture of the predictable and the unexpected. I correctly predicted six of the nominees, and happened to have already read seven of them, including Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (more on this below). I’m currently reading another from the longlist, Luster by Raven Leilani, and I have four on order from the library. There are only four that I don’t plan to read, so I’ll be in a fairly good place to predict the shortlist (due out on April 28th). Laura and Rachel wrote detailed reaction posts on which there has been much chat.

Rathbones Folio Prize

This year I read almost the entire Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist because I was lucky enough to be sent the whole list to feature on my blog. The winner, which the Rathbones CEO said would stand as the “best work of literature for the year” out of 80 nominees, was announced on Wednesday in a very nicely put together half-hour online ceremony hosted by Razia Iqbal from the British Library. The Folio scheme also supports writers at all stages of their careers via a mentorship scheme.

It was fun to listen in as the three judges discussed their experience. “Now nonfiction to me seems like rock ‘n’ roll,” Roger Robinson said, “far more innovative than fiction and poetry.” (Though Sinéad Gleeson and Jon McGregor then stood up for the poetry and fiction, respectively.) But I think that was my first clue that the night was going to go as I’d hoped. McGregor spoke of the delight of getting “to read above the categories, looking for freshness, for excitement.” Gleeson said that in the end they had to choose “the book that moved us, that enthralled us.”

All eight authors had recorded short interview clips about their experience of lockdown and how they experiment with genre and form, and seven (all but Doireann Ní Ghríofa) were on screen for the live announcement. The winner of the £30,000 prize, author of an “exceptional, important” book and teller of “a story that had to be told,” was Carmen Maria Machado for In the Dream House. I was delighted with this result: it was my first choice and is one of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve read. I remember reading it on my Kindle on the way to and from Hungerford for a bookshop event in early March 2020 – my last live event and last train ride in over a year and counting, which only made the reading experience more memorable.

I like what McGregor had to say about the book in the media release: “In the Dream House has changed me – expanded me – as a reader and a person, and I’m not sure how much more we can ask of the books that we choose to celebrate.”

There are now only two previous Folio winners that I haven’t read, the memoir The Return by Hisham Matar and the novel Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, so I’d like to get those two out from the library soon and complete the set.

Other literary prizes

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

I also tuned into the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards ceremony (on YouTube), which was unfortunately marred by sound issues. This year’s three awards went to women: Dervla Murphy (Edward Stanford Outstanding Contribution to Travel Writing), Anita King (Bradt Travel Guides New Travel Writer of the Year; you can read her personal piece on Syria here), and Taran N. Khan for Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul (Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year in association with the Authors’ Club).

Other prize races currently in progress that are worth keeping an eye on:

- The Jhalak Prize for writers of colour in Britain (I’ve read four from the longlist and would be interested in several others if I could get hold of them)

- The Republic of Consciousness Prize for work from small presses (I’ve read two; Doireann Ní Ghríofa gets another chance – fingers crossed for her)

- The Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction (next up for me: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams, to review for BookBrowse)

Claire Fuller

Yesterday evening, I attended the digital book launch for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (my review will be coming soon). I’ve read all four of her novels and count her among my favorite contemporary writers. I spotted Eric Anderson and Ella Berthoud among the 200+ attendees, and Claire’s agent quoted from Susan’s review – “A new novel from Fuller is always something to celebrate”! Claire read a passage from the start of the novel that introduces the characters just as Dot starts to feel unwell. Uniquely for online events I’ve attended, we got a tour of the author’s writing room, with Alan the (female) cat asleep on the daybed behind her, and her librarian husband Tim helped keep an eye on the chat.

After each novel, as a treat to self, she buys a piece of art. This time, she commissioned a ceramic plate from Sophie Wilson with lines and images from the book painted on it. Live music was provided by her son Henry Ayling, who played acoustic guitar and sang “We Roamed through the Garden,” which, along with traditional folk song “Polly Vaughn,” are quoted in the novel and were Claire’s earworms for two years. There was also a competition to win a chocolate Easter egg, given to whoever came closest to guessing the length of the new novel in words. (It was somewhere around 89,000.)

Good news – she’s over halfway through Book 5!

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

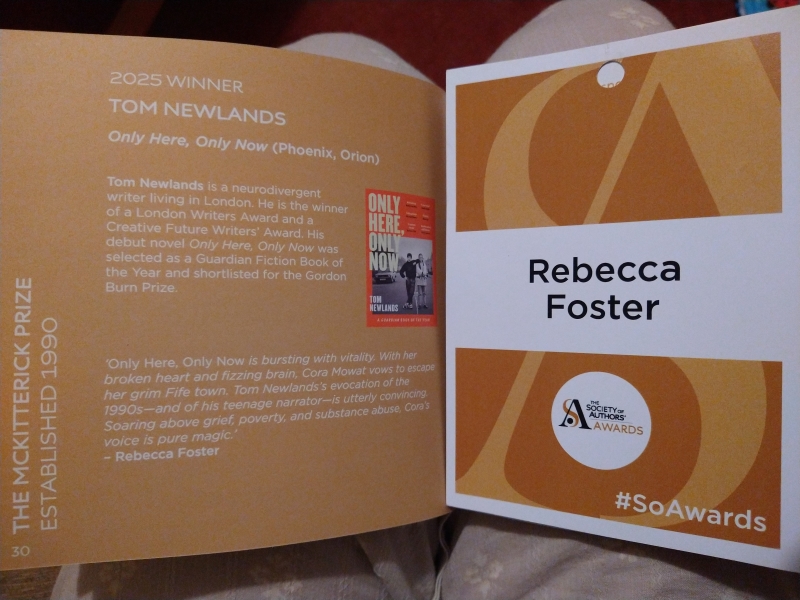

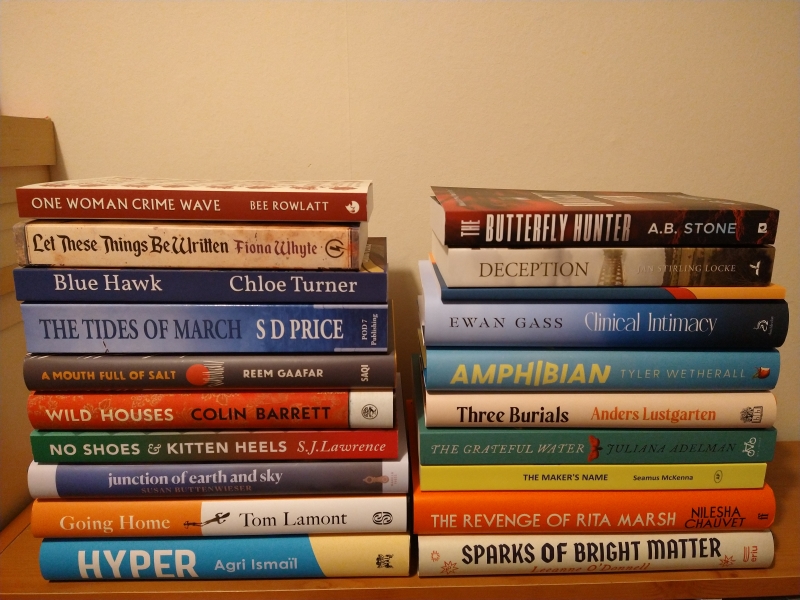

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

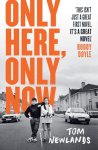

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

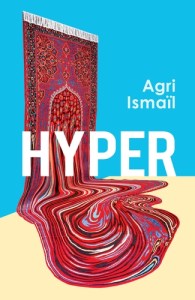

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

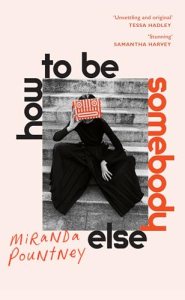

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

Dialogue is given in italics in the memoirs The Tidal Year by Freya Bromley and The Unfamiliar by Kirsty Logan.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

The Russian practice of whipping people with branches at a spa in Tiger by Polly Clark and Fight Night by Miriam Toews.

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s  Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]  “She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]  The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs,  It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]  I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018:  I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]  I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]  This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]