Literary Wives Club: Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell (1959)

This is the best thing we’ve read in my time with the Literary Wives online book club (out of 16 books so far). In the early pages it reminded me of Richard Yates’s work, but by the end I was thinking of it as on par with Stoner by John Williams, a masterpiece I reread last year. Is Mrs. Bridge a female Stoner? In that she is an Everywoman, representative of a certain comfortable, conventional interwar life but also of common longings to be purposeful, experience novelty, and connect with others – I’d say yes. From the first line onwards, we see her as at odds with the facts of her life, which at least appear to her to be unalterable: “Her first name was India – she was never able to get used to it.” She’s never lived up to her exotic name, she feels; her parents must have expected something of her that she couldn’t be.

Connell (1924–2013) sets this portrait of a marriage in his native Kansas City, Missouri. The story is not contemporaneous to its publication but begins in the 1930s; this doesn’t become clear until two-thirds of the way through when, on a European tour that workaholic lawyer Walter Bridge arranged as a belated birthday gift to his wife, news comes that the Nazis have invaded Poland and they have to hurry home. Bear in mind that this is the man who refused to move when a tornado threatened their country club and every single other person had moved to the basement. He insisted on staying at the table and finishing his steak. (So … he expects the weather to bow to his will, if not world leaders?) It’s an astonishing scene, and occasions an astute summation of their relationship dynamic:

It did not occur to Mrs Bridge to leave her husband and run to the basement. She had been brought up to believe without question that when a woman married she was married for the rest of her life and was meant to remain with her husband wherever he was, and under all circumstances, unless he directed her otherwise. She wished he would not be so obstinate; she wished he would behave like everyone else, but she was not particularly frightened. For nearly a quarter of a century she had done as he told her, and what he had said would happen had indeed come to pass, and what he had said would not occur had not occurred. Why, then, should she not believe him now?

(That attitude of blind faith seems more appropriate in a father–daughter or God–mortal relationship than husband–wife, does it not?)

The structure of the book must have been groundbreaking for its time: it’s in 117 short, titled vignettes – a fragmentary style later popularized by writers such as Elizabeth Hardwick, Sarah Manguso and Jenny Offill – that build a picture of the protagonist and her milieu. Even though many of them seem to concern minor incidents from the Bridges’ social life (parties, gossip, the bores they’re forced to have lunch with every time they’re in town), they also reveal a lot about India’s outlook. She wears stockings even on the hottest summer days because “it was the way things were, it was the way things had always been, and so she complied.” Like many of her time and place, she is a casual racist, evidenced by comments on her children’s Black and “gypsy” friends. It pains her that she doesn’t understand her three children. To her it seems they do strange, shocking things (okay, Douglas building a tower of junk is pretty weird) when really they’re just experimenting with fashion and sexuality as any teenager would.

India is in awe of the women of her acquaintance who step out of line, like Grace Barron and Mabel Ong. Grace, in particular, is well informed and confident arguing with men. India seriously considers breaking away from Walter and voting liberal at the next election, but loses her nerve at the last minute; her viewpoint is fundamentally conservative. The novel justifies this by showing how those who flout social rules are shamed or punished in some way.

Mostly, India feels pointless. With a housekeeper around, there’s nothing for her to do. She has nothing but leisure time she doesn’t know how to fill. And yet the years fly past, propelling her into middle age. Occasionally, she’ll summon the motivation to sign up for painting classes or start learning Spanish via records, but she never follows through. So it’s just unnecessary shopping trips in a massive Lincoln she never figures out how to park properly.

She spent a great deal of time staring into space, oppressed by the sense that she was waiting. But waiting for what? She did not know. Surely someone would call, someone must be needing her. Yet each day proceeded like the one before. … Time did not move. The home, the city, the nation, and life itself were eternal; still she had a foreboding that one day, without warning and without pity, all the dear, important things would be destroyed.

It may be fashionable to scorn the existential despair of the privileged, but this is a potent picture of a universal condition. It’s all too easy to get stuck in the status quo and feel helpless to change life for the better. I came across a Slightly Foxed article (Spring 2016) by William Palmer, “The Sadness of Mrs Bridge.” Palmer suggests that Connell was an oddity to his publishers because he wrote in so many genres, and never the same kind of book twice. He dubs this Connell’s finest work. I marked out a couple of passages from his appreciation:

The genius of Connell is to show that this is how most people live: first in their own minds, then in their families, then in their limited social circles; most historical novels fail to realize that most people simply do not notice whatever great moments of history are being enacted around them unless they actually impinge upon their lives.

What is truly compelling about Mrs Bridge is her very ordinariness, notwithstanding all her petty snobbery, conformism and timidity. The list is easy to make and appears to be a fairly damning indictment, but Connell is not writing a satirical portrait. His intention is to show us the utter uniqueness of this one human life, irreplaceability of body and soul that is India Bridge. Connell portrays her so tenderly that we come to sympathize with her and, more, to care for her.

{SOME SPOILERS IN THE REMAINDER}

The way Mrs. Bridge ends indicates that Mr. Bridge, which was published 10 years later, will be not a sequel but a companion piece. I’m somewhat wary of reading it, but it will be intriguing to see how events overlap and to what extent Connell is able to make Walter a more sympathetic character. (Palmer remarks, “It is terrifying how little the two portraits have in common – they might be describing two entirely different worlds.”) Connell’s work remains influential: Claire Fuller has featured the pair of novels in one of her year-end reading roundups, and the husband’s surname in Manguso’s Liars is Bridges.

I’ve written much more than I intended to about Mrs. Bridge, but wanted to do justice to what will no doubt be one of my stand-out reads of the year.

(My omnibus edition came from the free bookshop we used to have in the local mall.) ![]()

The main question we ask about the books we read for Literary Wives is:

What does this book say about wives or about the experience of being a wife?

Based on Mrs. Bridge’s experience, one would be excused for thinking that being a wife involves the complete suppression of one’s own personality, ambitions and desires – including sexual, as dealt with very succinctly in the first chapter: Walter usually initiates; the one time she tries to do so, he gives her a patronizing hug and falls asleep. “This was the night Mrs Bridge concluded that while marriage might be an equitable affair, love itself was not.” A wry statement from Connell as marriage is certainly not equitable in this novel.

Granted, this was the 1910s–1930s. By the 1940s, when her daughters are young women, they’re determined to live differently, the one by becoming a New York City career girl, single and promiscuous. The other also vows to do things differently – “Listen, Mother, no man is ever going to push me around the way Daddy pushes you around” – yet ends up pregnant and battered. When India tries to encourage her to placate her husband through sex, she replies, “Oh no, don’t tell me that! I don’t want any part of that myth.”

So we see attitudes starting to change, but it would be another couple of decades before there were more options for both of these generations of women.

A common observation in many of the novels we’ve considered is that, even in a marriage, it is possible for the partners to be a complete mystery to each other. I’ll be interested to see whether Walter’s side of the story illuminates anything or portrays him as clueless. And a main moral I draw from most of our reads is that defining oneself by any relationship – mostly marriage, but also parenthood – sets one up for disappointment, or worse.

See the reviews by Becky, Kate, Kay and Naomi, too!

We recently welcomed a new member, Marianne, and will soon be choosing our books for the next two-plus years. Here’s the club page on Kay’s blog with the current members’ profiles plus all the books covered since 2013.

Our next selection will be Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri in June. I’ve not read Lahiri before but have always meant to, so I’m particularly looking forward to this one.

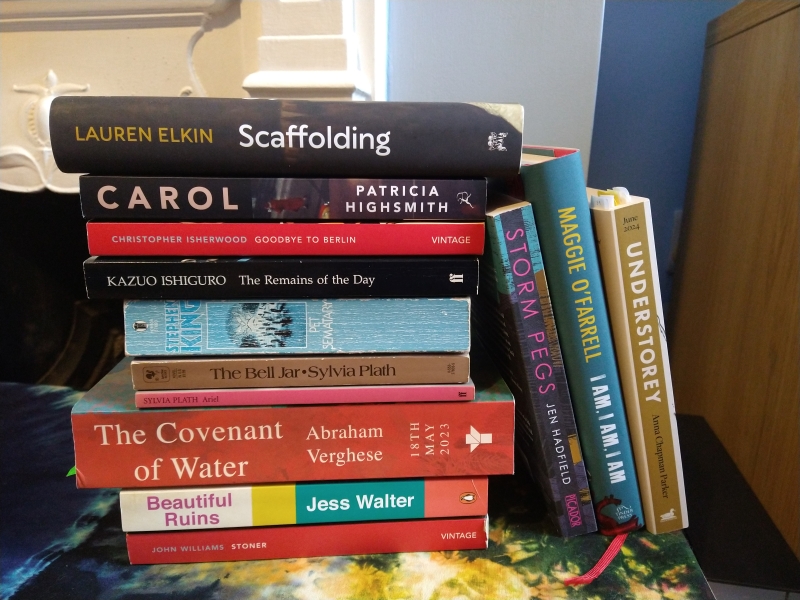

Best Backlist Reads of the Year

I consistently find that many of my most memorable reads are older rather than current-year releases. Four of these are from 2023–4; the other nine are from 2012 or earlier, with the oldest from 1939. My selections are alphabetical within genre but in no particular rank order. Repeated themes included health, ageing, death, fascism, regret and a search for home and purpose. Reading more from these authors would probably help to ensure a great reading year in 2026!

Some trivia:

- 4 were read for 20 Books of Summer (Hadfield, King, Verghese and Walter)

- 3 were rereads for book club (Ishiguro, O’Farrell and Williams) – just like last year!

- 1 was part of my McKitterick Prize judge reading (Elkin)

- 1 was read for 1952 Club (Highsmith)

- 1 was a review catch-up book (Parker)

- 1 was a book I’d been ‘reading’ since 2021 (The Bell Jar)

- The title of one (O’Farrell) was taken from another (The Bell Jar)

Fiction & Poetry

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin: Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in this intellectual tour de force. As history repeats itself during one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. This was our collective runner-up for the 2025 McKitterick Prize, but would have been my overall winner.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith: Widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer, meets a wealthy housewife – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – in a New York City department store one Christmas. When the women set off on a road trip, they’re trailed by a private detective looking for evidence against Carol in a custody battle. It’s a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds and shares the psychological intensity of Highsmith’s mysteries.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood: Isherwood intended for these autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin.” Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 reveal a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. Famously, the longest story introduces club singer Sally Bowles. I later read Mr Norris Changes Trains as well. Witty and humane, restrained but vigilant.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro: I first read this pre-blog, back when I dutifully read Booker winners whether or not I expected to like them. I was too young then for its theme of regret over things done and left undone; I didn’t yet know that sometimes in life, it really is too late. When I reread it for February book club, it hit me hard. I wrote no review at the time (more fool me), but focused less on the political message than on the refined depiction of upper-crust English society and the brilliance of Stevens the unreliable, repressed narrator.

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King: A dread-laced novel about how we deal with the reality of death. Is bringing the dead back a cure for grief or a horrible mistake? A sleepy Maine town harbours many cautionary tales, and the Creeds have more than their fair share of sorrow. Louis is a likable protagonist whose vortex of obsession and mental health is gripping. In the last quarter, which I read on a long train ride, I couldn’t turn the pages any faster. Sterling entertainment, but also surprisingly poignant. (And not gruesome until right towards the end.)

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Bell Jar & Ariel by Sylvia Plath: Given my love of mental hospital accounts, it’s a wonder I’d not read this classic work of women’s autofiction before. Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. An enduringly relevant and absorbing read. / Ariel takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp and the first and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese: Wider events play out in the background (wars, partition, the fall of the caste system), but this saga sticks with one Kerala family in every generation of which someone drowns. I enjoyed the window onto St. Thomas Christianity, felt fond of all the characters, and appreciated how Verghese makes the Condition a cross between mystical curse and a diagnosable ailment. An intelligent soap opera that makes you think about storytelling, purpose and inheritance, this is extraordinary.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: I was captivated by the shabby glamour of Pasquale’s hotel in Porto Vergogna on the coast of northern Italy. A myriad of threads and formats – a movie pitch, a would-be Hemingway’s first chapter of a never-finished wartime opus, an excerpt from a producer’s autobiography and a play transcript – coalesce to flesh out what happened in the summer of 1962 and how the last half-century has treated all the supporting players. Warm, timeless and with great scenes, one of which had me in stitches. Fantastic.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Stoner by John Williams: What a quiet masterpiece. A whole life, birth to death, with all its sadness and failure and tragedy; but also joy and resistance and dignity. One doesn’t have to do amazing things that earn the world’s accolades to find vocation and meaning. Just as powerful a second time (I first read it in 2013). I was especially struck by the power plays in Stoner’s marriage and university department, and how well Williams dissects them. It’s more about atmosphere than plot – and that melancholy tone will stay with you.

Nonfiction

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield: Not a straightforward memoir but a set of atmospheric vignettes. Hadfield, a British Canadian poet, moved to Shetland in 2006 and soon found her niche. It’s a life of wild swimming, beachcombing, fresh fish, folk music, seabirds, kind neighbours, and good cheer that warms the long winter nights. After the isolation of the pandemic comes the unexpected joy of a partner and pregnancy in her mid-forties. I savoured this for its language and sense of place; it made me hanker to return to Shetland.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death by Maggie O’Farrell: (The final book club reread.) The memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for boring intermediate material. These pieces form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. The last two essays are the pinnacle.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

Understorey: A Year among Weeds by Anna Chapman Parker: I owe this a full review in the new year. Parker set out to study and sketch weeds as a way of cultivating attention and stillness as well as celebrating the everyday and overlooked. Daily drawings and entries bear witness to seasons changing but also to the minute alterations she observes in herself and her children. For me, this was all the more special because I’ve holidayed in Berwick-on-Tweed and could picture a lot of the ‘overgrown’ spaces she honours by making them her subjects.

What were some of your best backlist reads this year?

Some 2025 Reading Superlatives

Longest book read this year: The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese (724 pages)

Shortest book read this year: Sky Tongued Back with Light by Sébastien Luc Butler (a 38-page poetry chapbook coming out in 2026)

Authors I read the most by this year: Paul Auster and Emma Donoghue (3) [followed by Margaret Atwood, Chloe Caldwell, Michael Cunningham, Mairi Hedderwick, Christopher Isherwood, Rebecca Kauffman, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Maggie O’Farrell, Sylvia Plath and Jess Walter (2 each)]

Publishers I read the most from: (Besides the ubiquitous Penguin Random House and its myriad imprints) Faber (14), Canongate (12), Bloomsbury (11), Fourth Estate (7); Carcanet, Picador/Pan Macmillan and Virago (6)

My top author ‘discoveries’ of the year (I’m very late to the party on some of these!): poet Amy Gerstler, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen King, Elaine Kraf, Sylvia Plath, Chloe Savage’s children’s picture books (women + NB characters, science, adventure, dogs), Robin Stevens’s middle-grade mysteries, Jess Walter

Proudest book-related achievement: Clearing 90–100 books from my shelves as part of our hallway redecoration. Some I resold, some I gave to friends, some I put in the Little Free Library, and some I donated to charity shops.

Most pinching-myself bookish moment: Miriam Toews’ U.S. publicist e-mailing me about my Shelf Awareness review of A Truce That Is Not Peace to say, “saw your amazing review! Thank you so much for it – Miriam loved it!”

Books that made me laugh: LOTS, including Spent by Alison Bechdel (which I read twice), The Wedding People by Alison Espach, Victorian Psycho by Virginia Feito, Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler, The Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith, The Sacred Diary of Adrian Plass Aged 37 ¾, and Slags by Emma Jane Unsworth

A book that made me cry: Death of an Ordinary Man by Sarah Perry

Best book club selections: Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam; The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell and Stoner by John Williams (these three were all rereads)

Best first line encountered this year:

- From Leaving Atlanta by Tayari Jones: “Hard, ugly, summer-vacation-spoiling rain fell for three straight months in 1979.”

Best last lines encountered this year:

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane: “Death and love and life, all mingled in the flow.”

(Two quite similar rhetorical questions:)

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam: “If they didn’t know how it would end—with night, with more terrible noise from the top of Olympus, with bombs, with disease, with blood, with happiness, with deer or something else watching them from the darkened woods—well, wasn’t that true of every day?”

&

- Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter: “And even if they don’t find what they’re looking for, isn’t it enough to be out walking together in the sunlight?”

- Wreck by Catherine Newman: “You are still breathing.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

The Irish Goodbye by Beth Ann Fennelly: “Dear viewer of my naked body, Enjoy the bunions.”

- A Certain Smile by Françoise Sagan: “It was a simple story; there was nothing to make a fuss about.”

- Book of Lives by Margaret Atwood: “We scribes and scribblers are time travellers: via the magic page we throw our voices, not only from here to elsewhere, but also from now to a possible future. I’ll see you there.”

Book that put a song in my head every time I picked it up: The Harvest Gypsies by John Steinbeck (see Kris Drever’s song of the same name). Also, one story of Book of Exemplary Women by Diana Xin mentioned lyrics from “Wild World” by Cat Stevens (“Oh, baby, baby, it’s a wild world. And I’ll always remember you like a child, girl”).

Shortest book titles encountered: Pan (Michael Clune), followed by Gold (Elaine Feinstein) & Girl (Ruth Padel); followed by an 8-way tie! Spent (Alison Bechdel), Billy (Albert French), Carol (Patricia Highsmith), Pluck (Adam Hughes), Sleep (Honor Jones), Wreck (Catherine Newman), Ariel (Sylvia Plath) & Flesh (David Szalay)

Best 2025 book titles: Chopping Onions on My Heart by Samantha Ellis [retitled, probably sensibly, Always Carry Salt for its U.S. release], A Truce That Is Not Peace by Miriam Toews [named after a line from a Christian Wiman poem – top taste there] & Calls May Be Recorded for Training and Monitoring Purposes by Katharina Volckmer.

Best book titles from other years: Dreams of Dead Women’s Handbags by Shena Mackay

Biggest disappointments: Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – so not worth waiting 12 years for – and Heart the Lover by Lily King, which kind of retrospectively ruined her brilliant Writers & Lovers for me.

The 2025 books that it seemed like everyone was reading but I decided not to: Helm by Sarah Hall, The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji, What We Can Know by Ian McEwan (I’m 0 for 2 on his 2020s releases)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Both by Elaine Kraf: I Am Clarence and Find Him! (links to my Shelf Awareness reviews) are confusing, disturbing, experimental in language and form, but also ahead of their time in terms of their feminist content and insight into compromised mental states. The former is more accessible and less claustrophobic.

Book Serendipity, Mid-April to Mid-June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them down on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Raising a wild animal but (mostly) calling it by its species rather than by a pet name (so “Pigeon” and “the leveret/hare”) in We Should All Be Birds by Brian Buckbee and Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton.

- Eating hash cookies in New York City in Women by Chloe Caldwell and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A woman worries she’s left underclothes strewn about a room she’s about to show someone in one story of Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

The dialogue is italicized in Women by Chloe Caldwell and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- The ‘you know it when you see it’ definition (originally for pornography) is cited in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and Bookish by Lucy Mangan.

- Women (including the protagonist) weightlifting in a gym in Moderation by Elaine Castillo and All Fours by Miranda July.

- Miranda July, whose All Fours I was also reading at the time, was mentioned in Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung.

- A sibling story and a mystical light: late last year into early 2025 I read The Snow Queen by Michael Cunningham, and then I recognized this type of moment in Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- A lesbian couple with a furniture store in Carol [The Price of Salt] by Patricia Highsmith and one story of Are You Happy? by Lori Ostlund.

- Not being able to see the stars in Las Vegas because of light pollution was mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs, then in Moderation by Elaine Castillo.

- A gynaecology appointment scene in All Fours by Miranda July and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- An awkwardly tall woman in Heartwood by Amity Gaige, How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney, and Stoner by John Williams.

- The 9/11 memorial lights’ disastrous effect on birds is mentioned in The Wild Dark by Craig Childs and How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney.

- A car accident precipitated by an encounter with wildlife is key to the denouement in the novellas Women by Chloe Caldwell and Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz.

- The plot is set in motion by the death of an older brother by drowning, and pork chops are served to an unexpected dinner guest, in Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven and Days of Light by Megan Hunter, both of which I was reading for Shelf Awareness review.

- Kids running around basically feral in a 1970s summer, and driving a box of human ashes around in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Bug Hollow by Michelle Huneven.

- A character becomes a nun in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter.

- Wrens nesting just outside one’s front door in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Little Mercy by Robin Walter.

- ‘The female Woody Allen’ is the name given to a character in Women by Chloe Caldwell and then a description (in a blurb) of French author Nolwenn Le Blevennec.

- A children’s birthday party scene in Single, Carefree, Mellow by Katherine Heiny and Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec. A children’s party is also mentioned in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch.

- A man who changes his child’s nappies, unlike his father – evidence of different notions of masculinity in different generations, in Case Histories by Kate Atkinson, What My Father and I Don’t Talk About, edited by Michele Filgate, and one piece in Beyond Touch Sites, edited by Wendy McGrath.

- What’s in a name? Repeated names I came across included Pansy (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and Days of Light by Megan Hunter), Olivia (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and A Family Matter by Claire Lynch), Jackson (Case Histories by Kate Atkinson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter), and Elias (Good Girl by Aria Aber and Dream State by Eric Puchner).

- The old wives’ tale that you should run in zigzags to avoid an alligator appeared in Alligator Tears by Edgar Gomez and then in The Girls Who Grow Big by Leila Mottley, both initially set in Florida.

- A teenage girl is groped in a nightclub in Good Girl by Aria Aber and Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann.

- Discussion of the extinction of human and animal cultures and languages in both Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, two May 2025 releases I was reading at the same time.

- In Body: My Life in Parts by Nina B. Lichtenstein, she mentions Linn Ullmann – who lived on her street in Oslo and went to the same school (not favourably – the latter ‘stole’ her best friend!); at the same time, I was reading Linn Ullmann’s Girl, 1983! And then, in both books, the narrator recalls getting a severe sunburn.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

On the same day, I read about otter sightings in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman and Spring by Michael Morpurgo. The next day, I read about nesting swallows in both books.

- The Salish people (Indigenous to North America) are mentioned in Lifelines by Julian Hoffman, Dream State by Eric Puchner (where Salish, the town in Montana, is also a setting), and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- Driving into a compound of extremists, and then the car being driven away by someone who’s not the owner, in Dream State by Eric Puchner and So Far Gone by Jess Walter.

- A woman worries about her (neurodivergent) husband saying weird things at a party in The Honesty Box by Lucy Brazier and Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal by Robin Ince.

- Shooting raccoons in Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson and So Far Gone by Jess Walter. (Raccoons also feature in Dream State by Eric Puchner.)

- A graphic novelist has Hollywood types adding (or at least threatening to add) wholly unsuitable supernatural elements to their plots in Spent by Alison Bechdel and Ginseng Roots by Craig Thompson.

- A novel in which a character named Dawn has to give up her daughter in the early 1980s, one right after the other: A Family Matter by Claire Lynch, followed by Love Forms by Claire Adam.

- A girl barricades her bedroom door for fear of her older brother in Love Forms by Claire Adam and Sleep by Honor Jones.

- A scene of an only child learning that her mother had a hysterectomy and so couldn’t have any more children in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Other People’s Mothers by Julie Marie Wade.

- An African hotel cleaner features in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Hotel by Daisy Johnson.

- Annie Dillard’s essay “Living Like Weasels” is mentioned in Nature’s Genius by David Farrier and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

- A woman assembles an inventory of her former lovers in Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and The Dry Season by Melissa Febos.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

#NovNov24 and #GermanLitMonth: Knulp by Hermann Hesse (1915)

My second contribution to German Literature Month (hosted by Lizzy Siddal) after A Simple Intervention by Yael Inokai. This was my first time reading the German-Swiss Nobel Prize winner Hermann Hesse (1877–1962). I had heard of his novels Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, of course, but didn’t know about any of his shorter works before I picked this up from the Little Free Library last month. Knulp is a novella in three stories that provide complementary angles on the title character, a carefree vagabond whose rambling years are coming to an end.

“Early Spring” has a first-person plural narrator, opening “Once, early in the nineties, our friend Knulp had to go to hospital for several weeks.” Upon his discharge he stays with an old friend, the tanner Rothfuss, and spends his time visiting other local tradespeople and casually courting a servant girl. Knulp is a troubadour, writing poems and songs. Without career, family, or home, he lives in childlike simplicity.

He had seldom been arrested and never convicted of theft or mendicancy, and he had highly respected friends everywhere. Consequently, he was indulged by the authorities very much, as a nice-looking cat is indulged in a household, and left free to carry on an untroubled, elegant, splendidly aristocratic and idle existence.

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

“My Recollections of Knulp” is narrated by a friend who joined him as a tramp for a few weeks one midsummer. It wasn’t all music and jollity; Knulp also pondered the essential loneliness of the human condition in view of mortality. “His conversation was often heavy with philosophy, but his songs had the lightness of children playing in their summer clothes.”

In “The End,” Knulp encounters another school friend, Dr. Machold, who insists on sheltering the wayfarer. They’re in their forties but Knulp seems much older because he is ill with tuberculosis. As winter draws in, he resists returning to the hospital, wanting to die as he lived, on his own terms. The book closes with an extraordinary passage in which Knulp converses with God – or his hallucination of such – expressing his regret that he never made more of his talents or had a family. ‘God’ speaks these beautiful words of reassurance:

Look, I wanted you the way you are and no different. You were a wanderer in my name and wherever you went you brought the settled folk a little homesickness for freedom. In my name, you did silly things and people scoffed at you; I myself was scoffed at in you and loved in you. You are my child and my brother and a part of me. There is nothing you have enjoyed and suffered that I have not enjoyed and suffered with you.

I struggle with episodic fiction but have a lot of time for the theme of spiritual questioning. The seasons advance across the stories so that Knulp’s course mirrors the year’s. Knulp could almost be a rehearsal for Stoner: a spare story of the life and death of an Everyman. That I didn’t appreciate it more I put down to the piecemeal nature of the narrative and an unpleasant conversation between Knulp and Machold about adolescent sexual experiences – as in the attempted gang rape scene in Cider with Rosie, it’s presented as boyish fun when part of what Knulp recalls is actually molestation by an older girl cousin. I might be willing to try something else by Hesse. Do give me recommendations! (Little Free Library) ![]()

Translated from the German by Ralph Manheim.

[125 pages]

Mini playlist:

- “Ramblin’ Man” by Lemon Jelly

- “I’ve Been Everywhere” by Johnny Cash

- “Rambling Man” by Laura Marling

- “Ballad of a Broken Man” by Duke Special

- “Railroad Man” by Eels

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

I have also recently read a 2025 release that counts towards these challenges, The Café with No Name by Robert Seethaler (Europa Editions; translated by Katy Derbyshire; 192 pages). The protagonist, Robert Simon [Robert S., eh? Coincidence?], is not unlike Knulp, though less blithe, or the unassuming Bob Burgess from Elizabeth Strout’s novels (e.g., Tell Me Everything). Robert takes over the market café in Vienna and over the next decade or so his establishment becomes a haven for the troubled. The Second World War still looms large, and disasters large and small unfold. It’s all rather melancholy; I admired the chapters that turn the customers’ conversation into a swirling chorus. In my review, pending for Foreword Reviews, I call it “a valedictory meditation on the passage of time and the bonds that last.”

European Traveling and Reading

We’ve been back from our European trip for over a week already, but I haven’t been up to writing until now. Partially this is because I’ve had a mild stomach bug that has left me feeling yucky and like I don’t want to spend any more time at a computer than is absolutely necessary for my work; partially it’s because I’ve just been a bit blue. Granted, it’s nice to be back where all the signs and announcements are in English and I don’t have to worry about making myself understood. Still, gloom over Brexit has combined with the usual letdown of coming back from an amazing vacation and resuming normal life to make this a ho-hum sort of week. Nonetheless, I want to get back into the rhythm of blogging and give a quick rundown of the books I read while I was away.

Tiny Lavin station, our base in southeastern Switzerland.

But first, some of the highlights of the trip:

- the grand architecture of the center of Brussels; live jazz emanating from a side street café

- cycling to the zoo in Freiburg with our friends and their kids

- ascending into the mountains by cable car and then on foot to circle Switzerland’s Lake Oeschinensee

- traipsing through meadows of Alpine flowers

- exploring the Engadine Valley of southeast Switzerland, an off-the-beaten track, Romansh-speaking area where the stone buildings are covered in engravings, paintings and sayings

- our one big splurge of the trip (Switzerland is ridiculously expensive; we had to live off of supermarket food): a Swiss dessert buffet followed by a horse carriage ride

- spotting ibex and chamois at Oeschinensee and marmots in the Swiss National Park

- miming “The Hills Are Alive” in fields near our accommodation in Austria (very close to where scenes from The Sound of Music were filmed)

- the sun coming out for our afternoon in Salzburg

- daily coffee and cake in Austrian coffeehouses

- riding the underground and trams of Vienna’s public transport network

- finding famous musicians’ graves in Vienna’s Zentralfriedhof cemetery

- discovering tasty vegan food at a hole-in-the-wall Chinese restaurant in Vienna that makes its own noodles

- going to Slovakia for the afternoon on a whim (its capital, Bratislava, is only 1 hour from Vienna by train – why not?!)

We went to such a variety of places and had so many different experiences. Weather and language were hugely variable, too: it rained nine days in a row; some mornings in Switzerland I wore my winter coat and hat; in Bratislava it was 95 °F. Even in the ostensibly German-speaking countries of the trip, we found that greetings and farewells changed everywhere we went (doubly true in the Romansh-speaking Engadine). Most of the time we had no idea what shopkeepers were saying to us. Just smile and nod. It was more difficult at the farm where we stayed in Austria. Thanks to Google Translate, we had no idea that the owner spoke no English; her e-mails were all in unusual but serviceable English. We speak virtually no German, so fellow farm guests, including a Dutch couple, had to translate between us. (The rest of Europe puts us to shame with their knowledge of languages!)

A reading-themed art installation at the Rathaus in Basel, Switzerland.

Train travel was, for the most part, easy and stress-free. Especially enjoyable were the small lines through the Engadine, which include the highest regular-service station in Europe (Ospizia Bernina, where we found fresh snowfall). The little town where we stayed in an Airbnb cabin, Lavin, was a request stop on the line, meaning you always had to press a button to get the train to stop and then walk across the tracks (!) to board. Contrary to expectations, we found that nearly all of our European trains were running late. However, they were noticeably more comfortable than British trains, especially the German ones. Thanks to train rides of an hour or more on most days, I ended up getting a ton of reading done.

On the journey out I finished The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler. This is the first “classic” Tyler I’ve read, after her three most recent novels, and although I kept being plagued by odd feelings of ‘reverse déjà vu’, I really enjoyed it. This story of staid, reluctant traveler Macon Leary and how his life is turned upside down by a flighty dog trainer is all about the patterns of behavior we get stuck in. Tyler suggests that occasionally journeying into someone else’s unpredictable life might change ours for the good.

On the journey out I finished The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler. This is the first “classic” Tyler I’ve read, after her three most recent novels, and although I kept being plagued by odd feelings of ‘reverse déjà vu’, I really enjoyed it. This story of staid, reluctant traveler Macon Leary and how his life is turned upside down by a flighty dog trainer is all about the patterns of behavior we get stuck in. Tyler suggests that occasionally journeying into someone else’s unpredictable life might change ours for the good.

Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome was just what I expected: a very silly book about the travails of international travel. It’s much more about the luckless journey and the endurance of national stereotypes than it is about the Passion Play the travelers see once they get to Germany. It was amusing to see the ways in which some things have hardly changed in 125 years.

Diary of a Pilgrimage by Jerome K. Jerome was just what I expected: a very silly book about the travails of international travel. It’s much more about the luckless journey and the endurance of national stereotypes than it is about the Passion Play the travelers see once they get to Germany. It was amusing to see the ways in which some things have hardly changed in 125 years.

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, a novella set in the Austrian Alps, is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler, a novella set in the Austrian Alps, is the story of Andreas Egger – at various times a farmer, a prisoner of war, and a tourist guide. Various things happen to him, most of them bad. I have trouble pinpointing why Stoner is a masterpiece whereas this is just kind of boring. There’s a great avalanche scene, though.

The Book that Matters Most by Ann Hood releases on August 9th. A new book club helps Ava cope with her divorce, her daughter Maggie’s rebelliousness, and tragic events from her past. Each month one club member picks the book that has mattered most to them in life. I thought the choices were all pretty clichéd and Ava was unrealistically passive. Although what happens to her in Paris is rather melodramatic, I most enjoyed Maggie’s sections.

The Book that Matters Most by Ann Hood releases on August 9th. A new book club helps Ava cope with her divorce, her daughter Maggie’s rebelliousness, and tragic events from her past. Each month one club member picks the book that has mattered most to them in life. I thought the choices were all pretty clichéd and Ava was unrealistically passive. Although what happens to her in Paris is rather melodramatic, I most enjoyed Maggie’s sections.

Me and Kaminski was my second novel from Daniel Kehlmann. Know-nothing art critic Sebastian Zöllner interviews reclusive artist Manuel Kaminski and then accompanies the older man on a road trip to find his lost sweetheart. Zöllner is an amusingly odious narrator, but I found the plot a bit thin. This is a rare case where I would argue the book needs to be 100 pages longer.

Me and Kaminski was my second novel from Daniel Kehlmann. Know-nothing art critic Sebastian Zöllner interviews reclusive artist Manuel Kaminski and then accompanies the older man on a road trip to find his lost sweetheart. Zöllner is an amusingly odious narrator, but I found the plot a bit thin. This is a rare case where I would argue the book needs to be 100 pages longer.

About midway through the trip I finished another I’d started earlier in the month, This Is Where You Belong by Melody Warnick. The average American moves 11.7 times in their life. I’m long past that already. The book collects an interesting set of ideas about how to feel at home wherever you are: things like learning the place on foot, shopping and eating locally, and getting to know your neighbors. I am bad about integrating into a new community every time we move, so I picked up some good tips. Warnick uses examples from all over (though mostly U.S. locations), but also makes it specific to her home of Blacksburg, Virginia.

About midway through the trip I finished another I’d started earlier in the month, This Is Where You Belong by Melody Warnick. The average American moves 11.7 times in their life. I’m long past that already. The book collects an interesting set of ideas about how to feel at home wherever you are: things like learning the place on foot, shopping and eating locally, and getting to know your neighbors. I am bad about integrating into a new community every time we move, so I picked up some good tips. Warnick uses examples from all over (though mostly U.S. locations), but also makes it specific to her home of Blacksburg, Virginia.

“A cabinet of fantasies, a source of knowledge, a collection of lore from past and present, a place to dream… A bookshop can be so many things.” In A Very Special Year by Thomas Montasser, Valerie takes over Ringelnatz & Co. bookshop when the owner, her Aunt Charlotte, disappears. She has the entrepreneurial skills to run a business and gradually develops a love of books, too. The title book is a magical tome with blank pages that reveal the reader’s destination when the time is right. Twee but enjoyable; a quick read.

“A cabinet of fantasies, a source of knowledge, a collection of lore from past and present, a place to dream… A bookshop can be so many things.” In A Very Special Year by Thomas Montasser, Valerie takes over Ringelnatz & Co. bookshop when the owner, her Aunt Charlotte, disappears. She has the entrepreneurial skills to run a business and gradually develops a love of books, too. The title book is a magical tome with blank pages that reveal the reader’s destination when the time is right. Twee but enjoyable; a quick read.

Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens is a taut thriller set during one woman’s experience of childbirth in New York City in 2004. Flashbacks to how the patient and her Caribbean nurse got where they are now add emotional depth. Another very quick read.

Eleven Hours by Pamela Erens is a taut thriller set during one woman’s experience of childbirth in New York City in 2004. Flashbacks to how the patient and her Caribbean nurse got where they are now add emotional depth. Another very quick read.

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig is a psychologically astute novella in which a 12-year-old tries to interpret what’s happening between his mother and a fellow hotel guest, a baron he looks up to. For this naïve boy, many things come as a shock, including the threat of sex and the possibility of deception. This reminded me most of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. (On a hill above Salzburg we discovered a strange disembodied bust of Stefan Zweig, along with a plaque and a road sign.)

Burning Secret by Stefan Zweig is a psychologically astute novella in which a 12-year-old tries to interpret what’s happening between his mother and a fellow hotel guest, a baron he looks up to. For this naïve boy, many things come as a shock, including the threat of sex and the possibility of deception. This reminded me most of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. (On a hill above Salzburg we discovered a strange disembodied bust of Stefan Zweig, along with a plaque and a road sign.)

Playing Dead by Elizabeth Greenwood (releases August 9th) was great fun. Thinking of the six-figure education debt weighing on her shoulders, she surveys various cases of people who faked their own death or simply tried to disappear. Death fraud/“pseudocide” is not as easy to get away with as you might think. Fake drownings are especially suspect. I found most ironic the case of a man who lived successfully for 20 years under an assumed name but was caught when police stopped him for having a license plate light out. I particularly liked the chapter in which Greenwood travels to the Philippines, a great place to fake your death, and comes back with a copy of her own death certificate.

Playing Dead by Elizabeth Greenwood (releases August 9th) was great fun. Thinking of the six-figure education debt weighing on her shoulders, she surveys various cases of people who faked their own death or simply tried to disappear. Death fraud/“pseudocide” is not as easy to get away with as you might think. Fake drownings are especially suspect. I found most ironic the case of a man who lived successfully for 20 years under an assumed name but was caught when police stopped him for having a license plate light out. I particularly liked the chapter in which Greenwood travels to the Philippines, a great place to fake your death, and comes back with a copy of her own death certificate.

Miss Jane by Brad Watson (releases July 12th) is a historical novel loosely based on the story of the author’s great-aunt. Born in Mississippi in 1915, she had malformed genitals, which led to lifelong incontinence. Jane is a wonderfully plucky protagonist, and her friendship with her doctor, Ed Thompson, is particularly touching. “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries.” This reminded me most of What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, an excellent novel about living a full life and finding romance in spite of disability.

Miss Jane by Brad Watson (releases July 12th) is a historical novel loosely based on the story of the author’s great-aunt. Born in Mississippi in 1915, she had malformed genitals, which led to lifelong incontinence. Jane is a wonderfully plucky protagonist, and her friendship with her doctor, Ed Thompson, is particularly touching. “You would not think someone so afflicted would or could be cheerful, not prone to melancholy or the miseries.” This reminded me most of What Is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, an excellent novel about living a full life and finding romance in spite of disability.

I also left two novels unfinished (that’ll be for another post) and made progress in two other nonfiction titles. All in all, a great set of reading!

I’m supposed to be making my way through just the books we already own for the rest of the summer, but when I got back of course I couldn’t resist volunteering for a few new books available through Nudge and The Bookbag. Apart from a few blog reviews I’m bound to, my summer plan will be to give the occasional quick roundup of what I’ve read of late.

Frank and tender, this is a wonderful memoir about women’s reproductive choices – or the way life sometimes takes those choices out of your hands. Alden was happily married, with a beloved cat named Cecil and her first short story collection coming out soon. At age 39, she still hadn’t thought all that much about motherhood, but suddenly decision time was on her. Despite her ambivalence (“I might never have a child, and the irony is not lost on me, that I’m not even sure I want one”), she went ahead with multiple rounds of infertility treatment, only conceding defeat and grieving her loss when she was 42.

Frank and tender, this is a wonderful memoir about women’s reproductive choices – or the way life sometimes takes those choices out of your hands. Alden was happily married, with a beloved cat named Cecil and her first short story collection coming out soon. At age 39, she still hadn’t thought all that much about motherhood, but suddenly decision time was on her. Despite her ambivalence (“I might never have a child, and the irony is not lost on me, that I’m not even sure I want one”), she went ahead with multiple rounds of infertility treatment, only conceding defeat and grieving her loss when she was 42.