#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

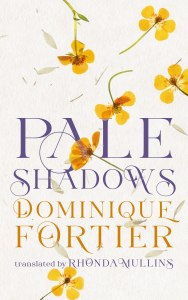

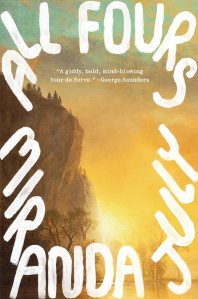

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)

(My full thoughts on both longlists are here.) The other two books on the Carol Shields Prize shortlist are River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure and Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin, about which I know very little. In its first two years, the Prize was awarded to women of South Asian extraction. Somehow, I can’t see the jury choosing one of three white women when it could be a Black woman (Lubrin) instead. However, Liars and All Fours feel particularly zeitgeist-y. I would be disappointed if the former won because of its bitter tone, though Manguso is an undeniable talent. Pale Shadows? Pure literary loveliness, if evanescent. But honouring a translation would make a statement, too. I’ll find out in the morning!

Poetry Month Reviews & Interview: Amy Gerstler, Richard Scott, Etc.

April is National Poetry Month in the USA, and I was delighted to have several of my reviews plus an interview featured in a special poetry issue of Shelf Awareness on Friday. I’ve also recently read Richard Scott’s second collection.

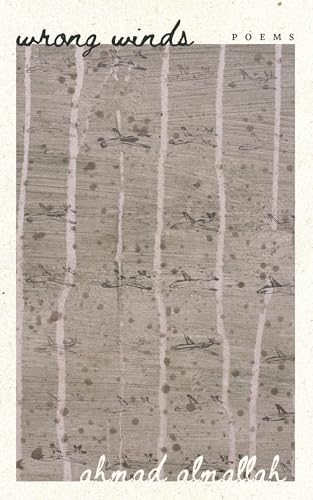

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s razor-sharp third collection bears witness to the devastation of Gaza.

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Tonally, anger and grief alternate, while alliteration and slant rhymes (sweat/sweet) create entrancing rhythms. In “Before Gaza, a Fall” and “My Tongue Is Tied Up Today,” staccato phrasing and spaced-out stanzas leave room for the unspeakable. The pièce de résistance is “A Holy Land, Wasted” (co-written with Huda Fakhreddine), which situates T.S. Eliot’s existential ruin in Palestine. Almallah contrasts Gaza then and now via childhood memories and adult experiences at checkpoints. His pastiche of “The Waste Land” starts off funny (“April is not that bad actually”) but quickly darkens, scorning those who turn away from tragedy: “It’s not good/ for your nerves to watch/ all that news, the sights/ of dead children.” The wordplay dazzles again here: “to motes the world crumbles, shattered/ like these useless mots.”

For Almallah, who now lives in Philadelphia, Gaza is elusive, enduringly potent—and mourned. Sometimes earnest, sometimes jaded, Wrong Winds is a remarkable memorial. ![]()

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. “As Winter Sets In” delivers “every day/ a new face you can’t renounce or forsake.” “When I was a bird,” with its interspecies metamorphoses, introduces a more fantastical concept: “I once observed a scurry of squirrels,/ concealed in a hollow tree, wearing seventeenth/ century clothes. Alas, no one believes me.” Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen.

The collection contains five thematic slices. Part I spotlights women behaving badly (such as “Marigold,” about a wild friend; and “Mae West Sonnet,” in an hourglass shape); Part II focuses on music and sound. The third section veers from the inherited grief of “Schmaltz Alert” to the miniplay “Siren Island,” a tragicomic Shakespearean pastiche. Part IV spins elegies for lives and works cut short. The final subset includes a tongue-in-cheek account of pandemic lockdown activities (“The Cure”) and wry advice for coping (“Wound Care Instructions”).

Monologues and sonnets recur—the title’s “form” refers to poetic structures as much as to personal identity. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance. In the closing poem, “Night Herons,” nature puts life into perspective: “the whir of wings/ real or imagined/ blurs trivial things.”

This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques.

I also had the chance to interview Amy Gerstler, whose work was new to me. (I’ll certainly be reading more!) We chatted about animals, poetic forms and tone, Covid, the Los Angeles fires, and women behaving ‘badly’. ![]()

Little Mercy by Robin Walter

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

Many of Walter’s poems are as economical as haiku. “Lilies” entrances with its brief lines, alliteration, and sibilance: “Come/ dark, white/ petals// pull/close// —small fists// of night—.” A poem’s title often leads directly into the text: “Here” continues “the body, yes,/ sometimes// a river—little/ mercy.” Vocabulary and imagery reverberate, as the blessings of morning sunshine and a snow-covered meadow salve an unquiet soul (“how often, really, I want/ to end my life”).

Frequent dashes suggest affinity with Emily Dickinson, whose trademark themes of loss, nature, and loneliness are ubiquitous here, too. Vistas of the American West are a backdrop for pronghorn antelope, timothy grass, and especially the wrens nesting in Walter’s porch. Animals are also seen in peril sometimes: the family dog her father kicked in anger or a roadkilled fox she encounters. Despite the occasional fragility of the natural world, the speaker is “held by” it and granted “kinship” with its creatures. (How appropriate, she writes, that her mother named her for a bird.)

The collection skillfully illustrates how language arises from nature (“while picking raspberries/ yesterday I wanted to hold in my head// the delicious names of the things I saw/ so as to fold them into a poem later”—a lovely internal rhyme) and becomes a memorial: “Here, on earth,/ we honor our dead// by holding their names/ gentle in our hollow mouths—.”

This poised, place-saturated collection illuminates life’s little mercies. ![]()

The three reviews above are posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

That Broke into Shining Crystals by Richard Scott

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

It also mirrors his debut in that the book is in several discrete sections – like movements of a musical composition – and there are extended allusions to particular poets (there, Paul Verlaine and Walt Whitman; here, Andrew Marvell and Arthur Rimbaud). But there is one overall theme, and it’s a tough one: Scott’s boyhood grooming and molestation by a male adult, and how the trauma continues to affect him.

Part I contains 21 “Still Life” poems based on particular paintings, mostly by Dutch or French artists (see the Notes at the end for details). I preferred to read the poems blind so that I didn’t have the visual inspiration in my head. The imagery is startlingly erotic: the collection opens with “Like a foreskin being pulled back, the damask / reveals – pelvic bowl of pink-fringed shadow” (“Still Life with Rose”) and “Still Life with Bananas” starts “curved like dicks they sit – cosy in wicker – an orgy / of total yellowness – all plenty and arching – beyond / erect – a basketful of morning sex and sugar and sunlight”.

“O I should have been the / snail,” the poet laments; “Living phallus that can hide when threatened. But / I’m the oyster. … Cold jelly mess of a / boy shucked wide open.” The still life format allows him to freeze himself at particular moments of abuse or personal growth; “still” can refer to his passivity then as well as to his ongoing struggle with PTSD.

Part II, “Coy,” is what Scott calls a found poem or “vocabularyclept,” rearranging the words from Marvell’s 1681 “To His Coy Mistress” into 21 stanzas. The constraint means the phrases are not always grammatical, and the section as a whole is quite repetitive.

The title of the book (and of its final section) comes from Rimbaud and, according to the Notes, the 22 poems “all speak back to Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations but through the prism of various crystals and semi-precious stones – and their geological and healing properties.” My lack of familiarity with Rimbaud and his circle made me wonder if I was missing something, yet I thrilled to how visual the poems in this section were.

As with the Still Lifes, there’s an elevated vocabulary, forming a rich panoply of plants, creatures, stones, and colours. Alliteration features prominently throughout, as in “Citrine”: “O citrine – patron saint of the molested, sunny eliminator – crown us with your polychromatic glittering and awe-flecks. Offer abundance to those of us quarried. A boy is igneous.”

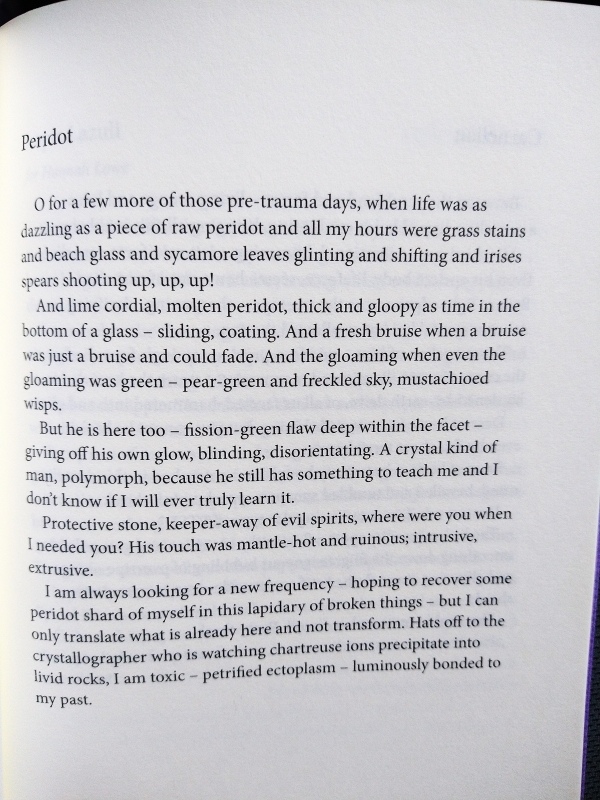

I’ve photographed “Peridot” (which was my mother’s birthstone) as an example of the before-and-after setup, the gorgeous language including alliteration, the rhetorical questioning, and the longing for lost innocence.

It was surprising to me that Scott refers to molestation and trauma so often by name, rather than being more elliptical – as poetry would allow. Though I admire this collection, my warmth towards it ebbed and flowed: I loved the first section; felt alienated by the second; and then found the third rather too much of a good thing. Perhaps encountering Part I or III as a chapbook would have been more effective. As it is, I didn’t feel the sections fully meshed, and the theme loses energy the more obsessively it’s repeated. Nonetheless, I’d recommend it to readers of Mark Doty, Andrew McMillan and Brandon Taylor. ![]()

Published today. With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. An abridged version of this review first appeared in my Instagram post of 11 April.

Read any good poetry recently?

Until the Future: “Tomorrow” Novels by Emma Straub & Gabrielle Zevin

These two 2022 novels I read from the library recently were such fun, but also had me fighting back tears – they’re lovely, bittersweet reads that think seriously about time and failure and loss (and prompted me to ask myself, “Was everything better in 1995–6?” The answer to which is an emphatic YES). If you’re a city-goer, you’ll appreciate the loving depictions of New York City and Los Angeles. They’re also perfect literary/ commercial crossovers that I can imagine recommending to just about any of my readers. Both:

This Time Tomorrow by Emma Straub

Emma Straub is one of the most reliable authors I know for highly readable literary fiction (see also: Jami Attenberg, Maggie O’Farrell and Ann Patchett): while there’s always a lot going on in terms of family dysfunction and character dynamics, her plots are juicy and the prose slides right down (especially Modern Lovers, as well as The Vacationers). Here Alice Stern is a frustrated 40-year-old who feels stuck career- and relationship-wise, working in admissions in the same NYC private school she once attended and living with an okay boyfriend she secretly hopes won’t propose. She devotes much of her emotional energy to her seriously ill father, Leonard, who it seems may never be released from the hospital.

Leonard is the one-hit sci-fi author of a cult classic about time travel, and when an inebriated Alice falls asleep near her childhood home on the night of her 40th birthday, she has her own time-travel adventure, waking up on her 16th birthday in 1996. This is her chance, she thinks: to make sure things go right with her high school crush, and to encourage her father to write more and adopt healthier habits so he won’t be dying in a hospital 24 years down the line. As she figures out the rules of this personal portal and attempts the same transition again and again, she starts to get the hang of what works; what she can change and what is inexorable. And she tries to be a better person, both then and now.

Leonard is the one-hit sci-fi author of a cult classic about time travel, and when an inebriated Alice falls asleep near her childhood home on the night of her 40th birthday, she has her own time-travel adventure, waking up on her 16th birthday in 1996. This is her chance, she thinks: to make sure things go right with her high school crush, and to encourage her father to write more and adopt healthier habits so he won’t be dying in a hospital 24 years down the line. As she figures out the rules of this personal portal and attempts the same transition again and again, she starts to get the hang of what works; what she can change and what is inexorable. And she tries to be a better person, both then and now.

True sci-fi aficionados would probably pick holes in the reasoning, but I would say so long as you pick this up expecting a smart commentary on relationships, ageing, loss and regret rather than a straight-up time-travel novel, you’ll be just fine. Straub is closer to my older sister’s age than mine, but I still loved the 1990s nostalgia, and looking back at your childhood/teen years from a parent’s perspective can only ever be an instructive thing to do.

It’s clever how Straub starts cycling through the time changes faster and faster so they don’t get repetitive. The supporting characters like Sam (Alice’s African American best friend), Kenji and even Ursula the cat are great, and there are little nods throughout to other pop culture representations of time travel. This was entertaining and relatable, but also left me with a lump in the throat. And it was all the more poignant to have been reading it just as news hit of author Peter Straub’s death; it’s a daughter’s tribute.

Some favourite lines:

(Alice thinking about Leonard) “She would feel immeasurably older when he was gone.”

“Maybe, she thought, … her mistake had been assuming that somewhere along the line, everything would fall into place and her life would look just like everyone else’s.”

(in 1996) “Everyone was gorgeous and gangly and slightly undercooked, like they’d been taken out of the oven a little bit too early”

“Any story could be a comedy or a tragedy, depending on where you ended it. That was the magic, how the same story could be told an infinite number of ways.”

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

I didn’t think I’d ever read another novel by Zevin after the dud that was The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry (by far my most popular negative review on Goodreads), but Laura’s fantastic review changed my mind.

Here’s the summary I wrote for Bookmarks magazine:

Sadie Green and Sam Masur met in unlikely circumstances. In 1986, Sam’s serious foot injury had him in a children’s hospital, where Sadie was visiting her sister, who had cancer. They hit it off talking video games, but Sam was hurt to learn Sadie kept up the visits to earn community service hours for her bat mitzvah. When they meet again during college in Boston, they decide to co-design a game. Helped by his roommate and her boyfriend, they create a bestseller, Ichigo, based on The Tempest. Over the decades, these gaming friends collaborate multiple times, but life throws some curveballs. A heartwarming story for gamers and the uninitiated alike.

The novel was more complicated than I expected, mostly because it spans nearly 30 years – and my main critique would probably be that a shorter timeline would have been more intense. It also goes to some dark places as it probes the two central characters’ traumas and tendency to depression. But their friendship, which over the years becomes a business partnership that also incorporates Sam’s college roommate, Marx Watanabe, is a joy. The creative energy and banter are enviable. Marx is the uncomplicated, optimistic go-between when Sam and Sadie butt heads and take offense at perceived betrayals. Underneath Sam and Sadie’s conflicts is a love different from, and maybe superior to, romantic love (I think Sam might best be described as ace).

The novel was more complicated than I expected, mostly because it spans nearly 30 years – and my main critique would probably be that a shorter timeline would have been more intense. It also goes to some dark places as it probes the two central characters’ traumas and tendency to depression. But their friendship, which over the years becomes a business partnership that also incorporates Sam’s college roommate, Marx Watanabe, is a joy. The creative energy and banter are enviable. Marx is the uncomplicated, optimistic go-between when Sam and Sadie butt heads and take offense at perceived betrayals. Underneath Sam and Sadie’s conflicts is a love different from, and maybe superior to, romantic love (I think Sam might best be described as ace).

Gaming comes across as better than reality in that it offers infinite possibilities for do-overs. Life, on the other hand, only goes in one direction and is constrained by choices, your own and others’. Part VII, “The NPC” (for non-player character), is in second person narration and is beautiful as well as heartbreaking – I’ll say no more for fear of spoilers.

Apart from playing Super Mario with older cousins at 1990s family reunions and a couple of educational computer games with my childhood best friend, I don’t have any history with gaming at all, yet Zevin really drew me in to the fictional worlds Sadie and Sam created with their games. What with the vivid imagery and literary allusions, EmilyBlaster, Ichigo and Master of the Revels are real works of art, bridging high and low culture and proving that Dickinson’s poetry and Shakespeare’s plays are truly timeless. I was also interested to see how games might be ahead of their time socio-politically.

This reminded me most of The Animators and The Art of Fielding, similarly immersive stories of friendship and obsessive commitment to work and/or play. In the same way that you don’t have to know anything about cartooning or baseball to enjoy those novels, you don’t have to be a gamer to find this a nostalgic, even cathartic, read.

Some favourite lines:

“for Marx, the world was like a breakfast at a five-star hotel in an Asian country—the abundance of it was almost overwhelming. Who wouldn’t want a pineapple smoothie, a roast pork bun, an omelet, pickled vegetables, sushi, and a green-tea-flavoured croissant? They were all there for the taking and delicious, in their own way.”

Sam to Sadie: “We work through our pain. That’s what we do. We put the pain into the work, and the work becomes better.”

Marx (who was a college actor) in the early years, citing Macbeth: “What is a game? It’s tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow. It’s the possibility of infinite rebirth, infinite redemption. The idea that if you keep playing, you could win. No loss is permanent, because nothing is permanent, ever.”

Two Memoirs by Freaks and Geeks Alumni

These days, I watch no television. At all. I haven’t owned a set in over eight years. But as a kid, teen and young adult, I loved TV. I devoured cartoons and reruns every day after school (Pinky and the Brain, I Love Lucy, Gilligan’s Island, The Brady Bunch, etc.); I was a devoted watcher of the TGIF line-up, and petitioned my parents to let me stay up late to watch Murphy Brown. We subscribed to the TV Guide magazine, and each September I would eagerly read through the pilot descriptions with a highlighter, planning which new shows I was going to try. It’s how I found ones like Alias, Felicity, Scrubs and 24 that I followed religiously. Starting in my freshman year of college, I was a mega-fan of American Idol for its first 12 seasons. And so on. Versus now I know nothing about what’s on telly and all the Netflix and box set hits have passed me by.

These days, I watch no television. At all. I haven’t owned a set in over eight years. But as a kid, teen and young adult, I loved TV. I devoured cartoons and reruns every day after school (Pinky and the Brain, I Love Lucy, Gilligan’s Island, The Brady Bunch, etc.); I was a devoted watcher of the TGIF line-up, and petitioned my parents to let me stay up late to watch Murphy Brown. We subscribed to the TV Guide magazine, and each September I would eagerly read through the pilot descriptions with a highlighter, planning which new shows I was going to try. It’s how I found ones like Alias, Felicity, Scrubs and 24 that I followed religiously. Starting in my freshman year of college, I was a mega-fan of American Idol for its first 12 seasons. And so on. Versus now I know nothing about what’s on telly and all the Netflix and box set hits have passed me by.

Ahem. On to the point.

Freaks and Geeks was my favourite show in high school (it aired in 1999–2000, when I was a junior) and the first DVD series I ever owned – a gift from my sister’s boyfriend, who became her first husband. It’s now considered a cult classic, but I can smugly say that I recognized its brilliance from the start. So did critics, but viewers? Not so much, or at least not enough; it was cancelled after just one season. I’ve vaguely followed the main actors’ careers since then, and though I normally don’t read celebrity autobiographies I’ve picked up two by former cast members in the last year. Both:

Yearbook by Seth Rogen (2021)

I have seen a few of Rogen’s (generally really dumb) movies. The fun thing about this autobiographical essay collection is that you can hear his deadpan voice in your head on every line. That there are three F-words within the first three paragraphs of the book tells you what to expect; if you have a problem with a potty mouth, you probably won’t get very far.

I have seen a few of Rogen’s (generally really dumb) movies. The fun thing about this autobiographical essay collection is that you can hear his deadpan voice in your head on every line. That there are three F-words within the first three paragraphs of the book tells you what to expect; if you have a problem with a potty mouth, you probably won’t get very far.

Rogen grew up Jewish in Vancouver in the 1980s and did his first stand-up performance at a lesbian bar at age 13. During his teens he developed an ardent fondness for drugs (mostly pot, but also mushrooms, pills or whatever was going), and a lot of these stories recreate the ridiculous escapades he and his friends went on in search of drugs or while high. My favourite single essay was about a trip to Amsterdam. He also writes about weird encounters with celebrities like George Lucas and Steve Wozniak. A disproportionately long section is devoted to the making of the North Korea farce The Interview, which I haven’t seen.

Seth Rogen speaking at the 2017 San Diego Comic Con International. Photo by Gage Skidmore, from Wikimedia Commons.

Individually, these are all pretty entertaining pieces. But by the end I felt that Rogen had told some funny stories with great dialogue but not actually given readers any insight into his own character; it’s all so much posturing. (Also, I wanted more of the how he got from A to B; like, how does a kid in Canada get cast in a new U.S. TV series?) True, I knew not to expect a sensitive baring of the soul, but when I read a memoir I like to feel I’ve been let in. Instead, the seasoned comedian through and through, Rogen keeps us laughing but at arm’s length.

This Will Only Hurt a Little by Busy Philipps (2018)

I hadn’t kept up with Philipps’s acting, but knew from her Instagram account that she’d gathered a cult following that she spun into modelling and paid promotions, and then a short-lived talk show hosting gig. Although she keeps up a flippant, sarcastic façade for much of the book, there is welcome introspection as she thinks about how women get treated differently in Hollywood. I also got what I wanted from the Rogen but didn’t get: insight into the how of her career, and behind-the-scenes gossip about F&G.

Philipps grew up first in the Chicago outskirts and then mostly in Arizona. She was a headstrong child and her struggle with anxiety started early. When she lost her virginity at age 14, it was actually rape, though she didn’t realize it at the time. At 15, she got pregnant and had an abortion. She developed a habit of seeking validation from men, even if it meant stringing along and cheating on nice guys.

I enjoyed reading about her middle and high school years because she’s just a few years older than me, so the cultural references were familiar (each chapter is named after a different pop song) and I could imagine the scenes – like one at a junior high dance where she got trapped in a mosh pit and dislocated her knee, the first of three times that specific injury happens in the book – taking place in my own middle school auditorium and locker hallway.

I enjoyed reading about her middle and high school years because she’s just a few years older than me, so the cultural references were familiar (each chapter is named after a different pop song) and I could imagine the scenes – like one at a junior high dance where she got trapped in a mosh pit and dislocated her knee, the first of three times that specific injury happens in the book – taking place in my own middle school auditorium and locker hallway.

She never quite made it to the performing arts summer camp she was supposed to attend in upstate New York, but did act in school productions and got an agent and headshots, so that when Mattel came to Scottsdale looking for actresses to play Barbie dolls in her junior year, she was perfectly placed to be cast as a live-action Cher from Clueless. She enrolled in college in Los Angeles (at LMU) but focused more on acting than on classes. After F&G, Dawson’s Creek was her biggest role. It involved moving to Wilmington, North Carolina and introduced her to her best friend, Michelle Williams, but she never felt she fit with the rest of the cast; her impression is that it was very much a star vehicle for Katie Holmes.

Busy Philipps at the Television Critics Association Awards in 2010. Photo by Greg Hernandez, from Wikimedia Commons.

Other projects that get a lot of discussion here are the Will Ferrell ice-skating movie Blades of Glory, which was her joint idea with her high school boyfriend Craig, and had a script written with him and his brother Jeff – there was big drama when they tried to take away her writing credit; and Cougar Town (with Courteney Cox), for which she won the inaugural Television Critics’ Choice Award. She auditioned a lot, including for TV pilots each year, but roles were few and far between, and she got rejected based on her size (when carrying baby weight after her daughters’ births, or once being cast as “the overweight friend”).

Anyway, I was here for the dish on Freaks and Geeks, and it’s juicy, especially about James Franco, who was her character Kim Kelly’s love interest on the show. Kim and Daniel had an on-again, off-again relationship, and the tension between them on camera reflected real life.

“Franco had come back from our few months off and was clearly set on being a VERY SERIOUS ACTOR … [he] had decided that the only way to be taken seriously was to be a fucking prick. Once we started shooting the series, he was not cool to me, at all. Everything was about him, always. His character’s motivation, his choices, his props, his hair, his wardrobe. Basically, he fucking bullied me. Which is what happens a lot on sets. Most of the time, the men who do this get away with it, and most of the time they’re rewarded.”

At one point, he pushed her over on the set; the directors slapped him on the wrist and made him apologize, but she knew nothing was going to come of it. Still, it was her big break:

what we were doing was totally different from the unrealistic teen shows every other network was putting out.

I didn’t know it then, but getting the call about was the first of many you-got-it calls I would get over the course of my career.

when [her daughter] Birdie turns thirteen, I’m going to watch the entire series with her.

And as a P.S., “Seth Rogen was cast as a guest star on [Dawson’s Creek] and he came out and did an episode with me, which was fun. He and Judd had brought me back to L.A. to do two episodes of Undeclared” & she was cast on one season of ER with Linda Cardellini.

The reason I don’t generally read celebrity autobiographies is that the writing simply isn’t strong enough. While Philipps conveys her voice and personality through her style (cursing, capital letters, cynical jokes), some of the storytelling is thin. I mean, there’s not really a chapter’s worth of material in an anecdote about her wandering off when she was two years old. And I think she overeggs it when she insists she’s always gone out and gotten what she wants; the number of rejections she’s racked up says otherwise. I did appreciate the #MeToo feminist perspective, though, looking back to her upbringing and the Harvey Weinsteins of the Hollywood world and forward to how she hopes things will be different for her daughters. I also admired her honesty about her mental health. But I wouldn’t really recommend this unless you are a devoted fan.

I loved these Freaks and Geeks-themed Valentines that a fan posted to Judd Apatow on Twitter this past February.

#NonFicNov: Being the Expert on Covid Diaries

This year the Be/Ask/Become the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Veronica of The Thousand Book Project. (In previous years I’ve contributed lists of women’s religious memoirs (twice), accounts of postpartum depression, and books on “care”.)

I’ve been devouring nonfiction responses to COVID-19 for over a year now. Even memoirs that are not specifically structured as diaries take pains to give a sense of what life was like from day to day during the early months of the pandemic, including the fear of infection and the experience of lockdown. Covid is mentioned in lots of new releases these days, fiction or nonfiction, even if just via an introduction or epilogue, but I’ve focused on books where it’s a major element. At the end of the post I list others I’ve read on the theme, but first I feature four recent releases that I was sent for review.

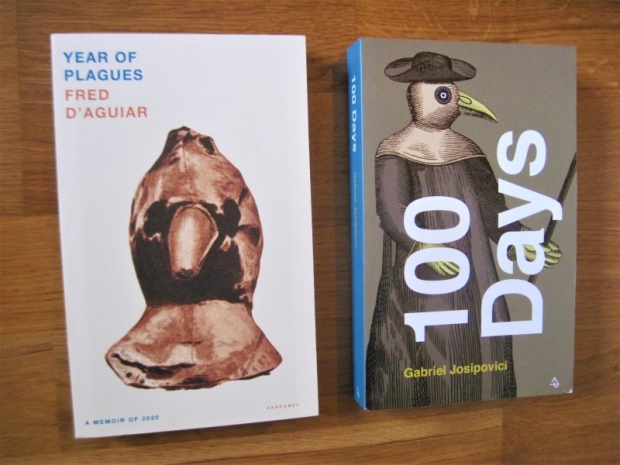

Year of Plagues: A Memoir of 2020 by Fred D’Aguiar

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

Cancer needs a song: tambourine and cymbals and a choir, not to raise it from the dead but [to] lay it to rest finally.

Tracing the effects of his cancer on his wife and children as well as on his own body, he wonders if the treatment will disrupt his sense of his own masculinity. I thought the narrative would hit home given that I have a family member going through the same thing, but it struck me as a jumble, full of repetition and TMI moments. Expecting concision from a poet, I wanted the highlights reel instead of 323 rambling pages.

(Carcanet Press, August 26.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Still, I appreciated Josipovici’s thoughts on literature and his own aims for his work (more so than the rehashing of Covid statistics and official briefings from Boris Johnson et al., almost unbearable to encounter again):

In my writing I have always eschewed visual descriptions, perhaps because I don’t have a strong visual memory myself, but actually it is because reading such descriptions in other people’s novels I am instantly bored and feel it is so much dead wood.

nearly all my books and stories try to force the reader (and, I suppose, as I wrote, to force me) to face the strange phenomenon that everything does indeed pass, and that one day, perhaps sooner than most people think, humanity will pass and, eventually, the universe, but that most of the time we live as though all was permanent, including ourselves. What rich soil for the artist!

Why have I always had such an aversion to first person narratives? I think precisely because of their dishonesty – they start from a falsehood and can never recover. The falsehood that ‘I’ can talk in such detail and so smoothly about what has ‘happened’ to ‘me’, or even, sometimes, what is actually happening as ‘I’ write.

You never know till you’ve plunged in just what it is you really want to write. When I started writing The Inventory I had no idea repetition would play such an important role in it. And so it has been all through, right up to The Cemetery in Barnes. If I was a poet I would no doubt use refrains – I love the way the same thing becomes different the second time round

To write a novel in which nothing happens and yet everything happens: a secret dream of mine ever since I began to write

I did sense some misogyny, though, as it’s generally female writers he singles out for criticism: Iris Murdoch is his prime example of the overuse of adjectives and adverbs, he mentions a “dreadful novel” he’s reading by Elizabeth Bowen, and he describes Jean Rhys and Dorothy Whipple as women “who, raised on a diet of the classic English novel, howled with anguish when life did not, for them, turn out as they felt it should.”

While this was enjoyable to flip through, it’s probably more for existing fans than for readers new to the author’s work, and the Covid connection isn’t integral to the writing experiment.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

A stanza from the below collection to link the first two books to this next one:

Have they found him yet, I wonder,

whoever it is strolling

about as a plague doctor, outlandish

beak and all?

The Crash Wake and Other Poems by Owen Lowery

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

As the seventh anniversary of his wedding to Jayne nears, Lowery reflects on how love has kept him going despite flashbacks to the accident and feeling written off by his doctors. In the second section of the book, the subjects vary from the arts (Paula Rego’s photographs, Stanley Spencer’s paintings, R.S. Thomas’s theology) to sport. There is also a lovely “Remembrance Day Sequence” imagining what various soldiers, including Edward Thomas and his own grandfather, lived through. The final piece is a prose horror story about a magpie. Like a magpie, I found many sparkly gems in this wide-ranging collection.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free e-copy for review.

Behind the Mask: Living Alone in the Epicenter by Kate Walter

[135 pages, so I’m counting this one towards #NovNov, too]

For Walter, a freelance journalist and longtime Manhattan resident, coronavirus turned life upside down. Retired from college teaching and living in Westbeth Artists Housing, she’d relied on activities outside the home for socializing. To a single extrovert, lockdown offered no benefits; she spent holidays alone instead of with her large Irish Catholic family. Even one of the world’s great cities could be a site of boredom and isolation. Still, she gamely moved her hobbies onto Zoom as much as possible, and welcomed an escape to Jersey Shore.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

There’s a lot here to relate to – being glued to the news, anxiety over Trump’s possible re-election, looking forward to vaccination appointments – and the book is also revealing on the special challenges for older people and those who don’t live with family. However, I found the whole fairly repetitive (perhaps as a result of some pieces originally appearing in The Village Sun and then being tweaked and inserted here).

Before an appendix of four short pre-Covid essays, there’s a section of pandemic writing prompts: 12 sets of questions to use to think through the last year and a half and what it’s meant. E.g. “Did living through this extraordinary experience change your outlook on life?” If you’ve been meaning to leave a written record of this time for posterity, this list would be a great place to start.

(Heliotrope Books, November 16.) With thanks to the publicist for the free e-copy for review.

Other Covid-themed nonfiction I have read:

Medical accounts

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

- Intensive Care by Gavin Francis

- Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer and Dan Koeppel (reviewed for Shelf Awareness)

- Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta

- Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

+ I have a proof copy of Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki, coming out in January.

Nature writing

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

- The Heeding by Rob Cowen (in poetry form)

- Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt

- The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

- Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss

General responses

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

- The Rome Plague Diaries by Matthew Kneale

- Quarantine Comix by Rachael Smith (in graphic novel form; reviewed for Foreword Reviews)

- UnPresidented by Jon Sopel

+ on my Kindle: Alone Together, an anthology of personal essays

+ on my TBR: What Just Happened: Notes on a Long Year by Charles Finch

If you read just one… Make it Intensive Care by Gavin Francis. (And, if you love nature books, follow that up with The Consolation of Nature.)

Without Saints: Essays by Christopher Locke: Fifteen flash essays present shards of a life story. Growing up in New Hampshire, Locke encountered abusive schoolteachers and Pentecostal church elders who attributed his stuttering to demon possession and performed an exorcism. By age 16, small acts of rebellion had ceded to self-harm, and his addictions persisted into adulthood. Later, teaching poetry to prisoners, he realized that he might have been in their situation had he been caught with drugs. The complexity of the essays advances alongside the chronology. Weakness of body and will is a recurrent element.

Without Saints: Essays by Christopher Locke: Fifteen flash essays present shards of a life story. Growing up in New Hampshire, Locke encountered abusive schoolteachers and Pentecostal church elders who attributed his stuttering to demon possession and performed an exorcism. By age 16, small acts of rebellion had ceded to self-harm, and his addictions persisted into adulthood. Later, teaching poetry to prisoners, he realized that he might have been in their situation had he been caught with drugs. The complexity of the essays advances alongside the chronology. Weakness of body and will is a recurrent element.

There’s a character named Verena in What Concerns Us by Laura Vogt and Summer by Edith Wharton. Add on another called Verona from Stories from the Tenants Downstairs by Sidik Fofana.

There’s a character named Verena in What Concerns Us by Laura Vogt and Summer by Edith Wharton. Add on another called Verona from Stories from the Tenants Downstairs by Sidik Fofana.

In Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell, Polly Pullar is mentioned as one of the writers at that year’s Wigtown Book Festival; I was reading her The Horizontal Oak at the same time.

In Remainders of the Day by Shaun Bythell, Polly Pullar is mentioned as one of the writers at that year’s Wigtown Book Festival; I was reading her The Horizontal Oak at the same time.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

The 11 stories in Erskine’s second collection do just what short fiction needs to: dramatize an encounter, or moment, that changes life forever. Her characters are ordinary, moving through the dead-end work and family friction that constitute daily existence, until something happens, or rises up in the memory, that disrupts the tedium.

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s

In form this is similar to O’Farrell’s  These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books.

These autobiographical essays were compiled by Quinn based on interviews he conducted with nine women writers for an RTE Radio series in 1985. I’d read bits of Dervla Murphy’s and Edna O’Brien’s work before, but the other authors were new to me (Maeve Binchy, Clare Boylan, Polly Devlin, Jennifer Johnston, Molly Keane, Mary Lavin and Joan Lingard). The focus is on childhood: what their family was like, what drove these women to write, and what fragments of real life have made it into their books. I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.

I didn’t realize when I started it that this was Tóibín’s debut collection; so confident is his verse that I assumed he’s been publishing poetry for decades. He’s one of those polymaths who’s written in many genres – contemporary fiction, literary criticism, travel memoir, historical fiction – and impresses in all. I’ve been finding his recent Folio Prize winner, The Magician, a little too dry and biography-by-rote for someone with no particular interest in Thomas Mann (I’ve only ever read Death in Venice), so I will likely just skim it before returning it to the library, but I can highly recommend his poems as an alternative.