Tag Archives: music

The 2024 Releases I’ve Read So Far

I happen to have read eight pre-release books so far, all of them for paid review; mostly for Shelf Awareness, with one for Foreword. (I also have proof copies of upcoming novels by Tania James, Margot Livesey, Sigrid Nunez and Sarah Perry on the shelf, but haven’t managed to start on them yet.) I’ve given review excerpts, links where available, and ratings below to try to pique your interest. Early in January I’ll follow up with a list of my dozen Most Anticipated titles for the coming year.

My top recommendations so far:

(in alphabetical order)

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali [Jan. 16, Alice James Books]: In this poised debut collection by a Muslim poet, spiritual enlightenment is a female, embodied experience, mediated by matriarchs. Ali’s ambivalence towards faith is clear in alliteration-laden verse that recalls Kaveh Akbar’s. Wordplay, floral metaphors, and multiple ghazals make for dazzling language.

Grief Is for People by Sloane Crosley [Feb. 27, MCD]: A bereavement memoir like no other. Heart-wrenching yet witty, it bears a unique structure and offers fascinating glimpses into the New York City publishing world. Crosley’s apartment was burgled exactly a month before the suicide of her best friend and former boss. Investigating the stolen goods in parallel serves as a displacement activity for her.

Grief Is for People by Sloane Crosley [Feb. 27, MCD]: A bereavement memoir like no other. Heart-wrenching yet witty, it bears a unique structure and offers fascinating glimpses into the New York City publishing world. Crosley’s apartment was burgled exactly a month before the suicide of her best friend and former boss. Investigating the stolen goods in parallel serves as a displacement activity for her.

Behind You Is the Sea by Susan Muaddi Darraj [Jan. 16, HarperVia]: Darraj’s second novel-in-stories is a sparkling composite portrait of a Palestinian American community in Baltimore. Across nine stellar linked stories, she explores the complex relationships between characters divided by—or connected despite—class, language, and traditional values. The book depicts the variety of immigrant and second-generation experience, especially women’s.

Behind You Is the Sea by Susan Muaddi Darraj [Jan. 16, HarperVia]: Darraj’s second novel-in-stories is a sparkling composite portrait of a Palestinian American community in Baltimore. Across nine stellar linked stories, she explores the complex relationships between characters divided by—or connected despite—class, language, and traditional values. The book depicts the variety of immigrant and second-generation experience, especially women’s.

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton [April 9, Scribner]: Many use the words “habit” and “ritual” interchangeably, but the Harvard Business School behavioral scientist argues convincingly that they are very different. While a habit is an automatic, routine action, rituals are “emotional catalysts that energize, inspire, and elevate us.” He presents an engaging and commonsense précis of his research, making a strong case for rituals’ importance in the personal and professional spheres as people mark milestones, form relationships, or simply “savor the experiences of everyday life.”

Other 2024 releases I’ve read:

(in publication date order)

House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

House Cat by Paul Barbera [Jan. 2, Thames & Hudson]: The Australian photographer Paul Barbera’s lavish art book showcases eye-catching architecture and the pets inhabiting these stylish spaces. Whether in a Revolutionary War-era restoration or a modernist show home, these cats preside with a befitting dignity. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

The Fox Wife by Yangsze Choo [Feb. 13, Henry Holt/Quercus]: Choo’s third novel is steeped in Chinese folklore, like her previous work, this time with a focus on tantalizing stories related to foxes, which were often worshiped at village shrines in China. Two tandem searches ramp up the level of suspense: in the winter of 1908 in Manchuria, in northeast China, a detective investigates a series of unexplained deaths; at the same time, a fox-woman masquerading as a servant plots vengeance against the man who murdered her child.

The Fox Wife by Yangsze Choo [Feb. 13, Henry Holt/Quercus]: Choo’s third novel is steeped in Chinese folklore, like her previous work, this time with a focus on tantalizing stories related to foxes, which were often worshiped at village shrines in China. Two tandem searches ramp up the level of suspense: in the winter of 1908 in Manchuria, in northeast China, a detective investigates a series of unexplained deaths; at the same time, a fox-woman masquerading as a servant plots vengeance against the man who murdered her child.

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)

The Only Way Through Is Out by Suzette Mullen [Feb. 13, University of Wisconsin Press]: A candid, inspirational memoir traces the events leading to her midlife acceptance of her lesbian identity and explores the aftermath of her decision to leave her marriage and build “a life where I would choose desire over safety.” The book ends on a perfect note as Mullen attends her first Pride festival aged 56. “It’s never too late” is the triumphant final line. (Foreword review forthcoming)

36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le [March 5, Knopf]: A fearless poetry debut prioritizes language and voice to explore inherited wartime trauma and expose anti-Asian racism. Each poem is titled after a rhetorical strategy or analytical mode. Anaphora is one sonic technique used to emphasize the points. Language and race are intertwined. This is a prophet’s fervent truth-telling. High-concept and unapologetic, this collection from a Dylan Thomas Prize winner pulsates. (Shelf Awareness review forthcoming)

Currently reading:

(in release date order; all for Shelf Awareness review)

God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.”

God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music by Leah Payne [Jan. 4, Oxford University Press]: “traces the history and trajectory of CCM in America and, in the process, demonstrates how the industry, its artists, and its fans shaped—and continue to shape—conservative, (mostly) white, evangelical Protestantism.”

Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.”

Raised by Wolves: Fifty Poets on Fifty Poems, A Graywolf Anthology [Jan. 23, Graywolf Press]: “Graywolf poets have selected fifty poems by Graywolf poets, offering insightful prose reflections on their selections. What arises is a choral arrangement of voices and lineages across decades, languages, styles, and divergences, inspiring a shared vision for the future.”

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl [April 30, Random House]: “When her estranged mother dies, Stella is left with an unusual gift: a one-way plane ticket, and a note reading ‘Go to Paris’. But Stella is hardly cut out for adventure … When her boss encourages her to take time off, Stella resigns herself to honoring her mother’s last wishes.”

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any other 2024 reads you can recommend?

That’s it for me until later next week when I start in on my year-end round-ups (DNFs, miscellaneous superlatives, books of the year, and final statistics). Merry Christmas!

Preposterous #NovNov23 Catch-Up Post

I have a big pile of novellas I read last month but never wrote about, plus a few more I’ve sneaked in by finishing them over the past couple of days. I tweaked my shoulder last weekend and the discomfort has moved into my neck, making daily life, and sleep, difficult. A taste of what it’s like to live with chronic pain, I suppose. Add in the freezing temperatures of recent days and I’ve been feeling pretty sorry for myself and haven’t succeeded in sitting at a computer for the time required to write at least a bit about these short books. But as today is the day our link-up finishes, I’m tucked up in bed with laptop, electric blanket, heater, cat, cup of tea and ice pack, ready to do all 16 the best justice I can through a paragraph each.

Fiction:

In the Sweep of the Bay by Cath Barton (2020)

Susan put this on my radar and I bought it in publisher Louise Walters Books’ closing-down sale. Set in Morecambe, this bittersweet story of a half-century marriage and the figures on its margins – co-workers, children, even strangers – is both ambitious and intimate. Ted and Rene Marshall marry in the 1950s and soon drift into drudgery and traditional gender roles; “They forgot the happiness. Or rather, they pushed it away.” While Ted becomes a celebrated ceramics designer in the family company, Rene stagnates at home. It is not so much suspected infidelity as simply taking each other for granted that threatens their relationship. Barton moves through the decades and varies the perspective, letting us hear from one of the Marshalls’ daughters and giving kind attention to a gay couple. Strictly Come Dancing fans and those familiar with the northwest might take particular pleasure, but I enjoyed this quiet book reminiscent of Anne Tyler’s French Braid and (though less political) Jonathan Coe’s Bournville. (New purchase) [104 pages]

Susan put this on my radar and I bought it in publisher Louise Walters Books’ closing-down sale. Set in Morecambe, this bittersweet story of a half-century marriage and the figures on its margins – co-workers, children, even strangers – is both ambitious and intimate. Ted and Rene Marshall marry in the 1950s and soon drift into drudgery and traditional gender roles; “They forgot the happiness. Or rather, they pushed it away.” While Ted becomes a celebrated ceramics designer in the family company, Rene stagnates at home. It is not so much suspected infidelity as simply taking each other for granted that threatens their relationship. Barton moves through the decades and varies the perspective, letting us hear from one of the Marshalls’ daughters and giving kind attention to a gay couple. Strictly Come Dancing fans and those familiar with the northwest might take particular pleasure, but I enjoyed this quiet book reminiscent of Anne Tyler’s French Braid and (though less political) Jonathan Coe’s Bournville. (New purchase) [104 pages]

The Visitor by Maeve Brennan (2000)

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

This posthumous novella was written in the 1940s but never published in Brennan’s lifetime. From Dublin, she was a longtime New Yorker staff member and wrote acclaimed short stories. After her mother’s death, Anastasia King travels from Paris, where the two set up residence after leaving her father, to Ireland to stay in the family home with her grandmother. Anastasia considers it a return, a homecoming, but her spiteful grandmother makes it clear that she is an unwelcome interloper. Mrs King can’t forgive the wrong done to her son, and so won’t countenance Anastasia’s plan to repatriate her mother’s remains. Rejection and despair eat away at Anastasia’s mental health (“She saw the miserable gate of her defeat already open ahead. There only remained for her to come up to it and pass through it and be done with it”) but she pulls herself together for an act of defiance. Most affecting for me was a scene in which we learn that Anastasia is so absorbed in her own drama that she does not fulfill the simple last wish of a dying friend. This brought to mind James Joyce’s The Dead. (Secondhand purchase – The Bookshop, Wigtown) [81 pages]

Bear by Marian Engel (1976)

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s The Pisces (stuffed full of sex with a merman). “I have an odd sense of being reborn,” Lou writes to her boss, the Institute director, with whom she’d been having an affair. The bear lives in an outbuilding and at first Lou is indifferent, only feeding him as necessary. Then he becomes a friend, joining her for swims. Then he comes into the house. Bestiality is a taboo for a reason, but what mostly bothers me is the lack of mutuality, the sense of taking advantage. I’m also wary of stories in which animals have a primarily instrumental or metaphorical role. Still, this was a solid read, offbeat and nearly as shocking today as when it first appeared. (Secondhand purchase online) [167 pages]

If you’ve heard of this, it’ll be for the fact that the main character – Lou, a librarian sent to archive the holdings of an octagonal house on an island one summer – has sex with a bear. That makes it sound much more repulsive and/or titillating than it actually is. The further I read the more I started to think of it as an allegory for women’s awakening; perhaps the strategy inspired Melissa Broder’s The Pisces (stuffed full of sex with a merman). “I have an odd sense of being reborn,” Lou writes to her boss, the Institute director, with whom she’d been having an affair. The bear lives in an outbuilding and at first Lou is indifferent, only feeding him as necessary. Then he becomes a friend, joining her for swims. Then he comes into the house. Bestiality is a taboo for a reason, but what mostly bothers me is the lack of mutuality, the sense of taking advantage. I’m also wary of stories in which animals have a primarily instrumental or metaphorical role. Still, this was a solid read, offbeat and nearly as shocking today as when it first appeared. (Secondhand purchase online) [167 pages]

So Late in the Day by Claire Keegan (2023)

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Several of us reviewed this for #NovNov though unsure it counts: in the UK the title story (originally for the New Yorker) was published in a standalone volume by Faber, while the U.S. release includes two additional earlier stories; I read the latter. The title story has Cathal spending what should have been his wedding weekend moping about Sabine calling off their engagement at the last minute. It’s no mystery why she did: his misogyny, though not overt, runs deep, most evident in the terms in which he thinks about women. And where did he learn it? From his father. (“The Long and Painful Death” is from Keegan’s second collection, Walk the Blue Fields, and concerns a woman on a writing residency at an author’s historic house in Ireland. She makes a stand for her own work by refusing to cede place to an entitled male scholar. The final story is “Antarctica,” the lead story in that 1999 volume and a really terrific one I’d already experienced before. It’s as dark and surprising as an early Ian McEwan novel.) Keegan proves, as ever, to be a master at portraying emotions and relationships, but the one story is admittedly slight on its own, and its point obvious. (Read via Edelweiss) [64 pages]

Swallowing Geography by Deborah Levy (1993)

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like Crudo, this has very little detail to latch onto and so was pretentious in its opacity. I’ve generally gotten on much better with Levy’s nonfiction (see below) than her fiction. This, along with the Keegan (above), was my chosen train entertainment for the Booker Prize evening. I got so little out of it that it seemed like wasted reading time. Here’s a decent excerpted passage: “The arrogance of metaphor when facts save people’s lives. The succour of metaphor when facts inadequately describe people’s lives.” (Public library) [83 pages]

“She is Europe’s eerie child, and she is part of the storm.” J.K. is a young woman who totes her typewriter around different European locations, sleeps with various boyfriends, hears strangers’ stories, and so on. Many of the people she meets are only designated by an initial. By contrast, the most fully realized character is her mother, Lillian Strauss. The chapters feel unconnected and the encounters within them random, building to nothing. Though a bit like Crudo, this has very little detail to latch onto and so was pretentious in its opacity. I’ve generally gotten on much better with Levy’s nonfiction (see below) than her fiction. This, along with the Keegan (above), was my chosen train entertainment for the Booker Prize evening. I got so little out of it that it seemed like wasted reading time. Here’s a decent excerpted passage: “The arrogance of metaphor when facts save people’s lives. The succour of metaphor when facts inadequately describe people’s lives.” (Public library) [83 pages]

Nonfiction:

Starting with two from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, a great source of short monographs. These have been among my favourites so far.

Grave by Allison C. Meier (2023)

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Meier is a cemetery tour guide in Brooklyn, where she lives. She surveys American burial customs in particular, noting the lack of respect for Black and Native American burial grounds, the Civil War-era history of embalming, the increasing popularity of cremation, and the rise of garden cemeteries such as Mount Auburn in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which can serve as wildlife havens. The mass casualties and fear of infection associated with Covid-19 brought back memories of the AIDS epidemic, especially for those in New York City. Meier travels to a wide range of resting places, from potter’s fields for unclaimed bodies to the most manicured cemeteries. She also talks about newer options such as green burial, body composting, and the many memorial objects ashes can be turned into. I’m a dedicated reader of books about death and so found this fascinating, with the perfect respectful and just-shy-of-melancholy tone. It’s political and philosophical in equal measures. (Read via NetGalley) [168 pages]

Pregnancy Test by Karen Weingarten (2023)

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

Laboratory pregnancy tests have been available since the 1930s and home pregnancy tests – the focus here – since the 1970s. All of them work by testing urine for the hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin). What is truly wild is that pregnancy used to be verifiable only with laboratory animals – female mice and rabbits had to be sacrificed to see if their ovaries had swelled after the injection of a woman’s urine; later, female Xenopus toads were found to lay eggs in response, so didn’t need to be killed. Home pregnancy kits were controversial and available in Canada before the USA because it was thought that they could be unreliable or that they would encourage early abortions. Weingarten brings together the history, laypeople-friendly science, and cultural representations (taking a pregnancy test is excellent TV shorthand) in a readable narrative and makes a clear feminist statement: “the home pregnancy test gave back to women what should have always been theirs: first-hand knowledge about how their bodies worked” and thus “had the potential to upend a paternalistic culture.” (Read via NetGalley) [160 pages]

And from a different Bloomsbury series for monographs about seminal albums, 33 1/3:

Jesus Freak by Will Stockton and D. Gilson (2019)

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

The dc Talk album Jesus Freak (1995) is the first CD I ever owned. My best friend and I listened to it (along with Bloom by Audio Adrenaline and Take Me to Your Leader by Newsboys) so many times that we knew every word and note by heart. So it’s hard for me to be objective rather than nostalgic; I was intrigued to see what two secular academics would have to say. Crucially, they were teenage dc Talk fans, now ex-Evangelicals and homosexual partners. As English professors, their approach is to spot musical influences (Nirvana on the title track; R&B and gospel elsewhere), critically analyse lyrics (with “Colored People” proving problematic for its “neoliberal multiculturalism and its potential for post-racial utopianism”), and put a queer spin on things. For those who don’t know, dc Talk were essentially a boy band with three singers, one Black and two white – one of these a rapper. Stockton and Gilson chronicle the confusion of living with a same-sex attraction they couldn’t express as teens, and cheekily suggest there may have been something going on between dc Talk members Toby McKeehan and Michael Tait, who were roommates at Liberty University and apparently dismantled their bunk beds so they could sleep side by side. Hmmm! I was interested enough in the subject matter to overlook the humanities jargon. (Birthday gift from my wish list last year) [132 pages]

And the rest:

Fifty Days of Solitude by Doris Grumbach (1994)

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs, Extra Innings and The Presence of Absence, when they were brought back into print as Open Road Media e-books. I knew of Grumbach through her association with May Sarton, and the two in fact had a lot in common, including lesbianism, living in Maine and writing about older age. I was expecting something on a par with Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude, one of my favourite books, but this fell short in comparison. Grumbach spent a month and a half alone in Maine during the winter of 1993 while her partner, Sybil, was away amassing stock for their bookstore. The book is a collection of unconnected meditations about nature, the cold, creativity and so on. She finds herself writing fiction so the characters can keep her company, and notes “how much more I was aware of my vices.” Although she tries to avoid the news, word reaches her of acquaintances’ demises, and she recalls the recent death from AIDS of a young local man. Amusingly, she rereads Bear (see above) during the 50 days. Some atmosphere, but low on insight. (Secondhand purchase – Wonder Book and Video, Hagerstown) [114 pages]

Grumbach died last year at age 104. This was my third of her books; I read two previous memoirs, Extra Innings and The Presence of Absence, when they were brought back into print as Open Road Media e-books. I knew of Grumbach through her association with May Sarton, and the two in fact had a lot in common, including lesbianism, living in Maine and writing about older age. I was expecting something on a par with Sarton’s Journal of a Solitude, one of my favourite books, but this fell short in comparison. Grumbach spent a month and a half alone in Maine during the winter of 1993 while her partner, Sybil, was away amassing stock for their bookstore. The book is a collection of unconnected meditations about nature, the cold, creativity and so on. She finds herself writing fiction so the characters can keep her company, and notes “how much more I was aware of my vices.” Although she tries to avoid the news, word reaches her of acquaintances’ demises, and she recalls the recent death from AIDS of a young local man. Amusingly, she rereads Bear (see above) during the 50 days. Some atmosphere, but low on insight. (Secondhand purchase – Wonder Book and Video, Hagerstown) [114 pages]

Things I Don’t Want to Know: On Writing by Deborah Levy (2013)

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

It feels like I made an error by reading Levy’s “Living Autobiography,” out of order. I picked up the middle volume of the trilogy, The Cost of Living, for #NovNov in 2021 and it ended up being my favourite nonfiction read of that year. I then read part of the third book, Real Estate, last year but set it aside. And now I’ve read the first because it was the shortest. It’s loosely structured around George Orwell’s four reasons for writing: political purpose, historical impulse, sheer egoism and aesthetic enthusiasm. The frame story has her flying to Majorca at a time when she was struggling with her mental health. She vaguely follows in the footsteps of George Sand and then pauses to tell a Chinese shopkeeper the story of her upbringing in apartheid-era South Africa and the family’s move to London. Although I generally admire recreations of childhood and there are some strong pen portraits of minor characters, overall there was little that captivated me here and I was too aware of the writerly shaping. (Secondhand purchase – 2nd & Charles, Hagerstown) [111 pages]

The Private Life of the Hare by John Lewis-Stempel (2019)

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018: The Secret Life of the Owl and The Glorious Life of the Oak. There’s a similar range of material here: anatomy, natural history and cultural significance, including in poetry. There are chapters on hunting, the hare as food, and its appearances in myth and religion. I was engaged about half of the time; I tended to skip over longer excerpts from historical documents. The reliance on lengthy quotations and use of bullet points make it feel like a half-finished research project, with the kind of information you could find anywhere else. Too many of his recent books have felt like they were rushed into print. I would only pick this up if you’re particularly fascinated by hares. (Public library) [99 pages]

I reviewed a couple of JLS’s species-specific monographs for #NovNov in 2018: The Secret Life of the Owl and The Glorious Life of the Oak. There’s a similar range of material here: anatomy, natural history and cultural significance, including in poetry. There are chapters on hunting, the hare as food, and its appearances in myth and religion. I was engaged about half of the time; I tended to skip over longer excerpts from historical documents. The reliance on lengthy quotations and use of bullet points make it feel like a half-finished research project, with the kind of information you could find anywhere else. Too many of his recent books have felt like they were rushed into print. I would only pick this up if you’re particularly fascinated by hares. (Public library) [99 pages]

The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde (1980)

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

I’ve read so many cancer stories that it takes a lot to make one stand out. This feels like a random collection of documents rather than a coherent memoir. One of the three essays was originally a speech, and two were previously printed in another of her books. Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. A Black lesbian feminist, she resisted wearing prostheses and spoke up about the potential environmental causes of breast cancer that need to be addressed in research (“I may be a casualty in the cosmic war against radiation, animal fat, air pollution, McDonald’s hamburgers and Red Dye No. 2”). Her actual journal entries make up little of the text, which is for the best because fear and pain can bring out the cliches in us – but occasionally a great quote like “if bitterness were a whetstone, I could be sharp as grief.” Another favourite line: “Pain does not mellow you, nor does it ennoble, in my experience.” I’m keen to read her memoir Zami. (University library) [77 pages]

A Month in Siena by Hisham Matar (2019)

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

I’d not read Matar before I spotted this art book-cum-memoir and thought, why not. A Libyan American novelist who lives in London, Matar had long been fascinated by the Sienese School of painting (13th to 15th centuries), many of whose artists depicted biblical scenes or religious allegories – even though he’s not a Christian. He spent a month in Italy immersed in the art he loves; there are 15 colour reproductions here. His explications of art history are generalist enough to be accessible to all readers, but I engaged more with the glimpses into his own life. For instance, he meets a fellow Arabic speaker and they quickly form a brotherly attachment, and a Paradise scene gives him fanciful hope of being reunited with his missing father – the subject of his Folio Prize-winning memoir The Return, which I’d like to read soon. His prose is beautiful as he reflects on history, death and how memories occupy ‘rooms’ in the imagination. A little more interest in the art would have helped, though. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

A Childhood in Scotland by Christian Miller (1981)

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

I had high hopes for this childhood memoir that originally appeared in the New Yorker and was reprinted as part of the Canongate Classics series. But I soon resorted to skimming as her recollections of her shabby upper-class upbringing in a Highlands castle are full of page after page of description and dull recounting of events, with few scenes and little dialogue. This would be of high historical value for someone wanting to understand daily life for a certain fraction of society at the time, however. When Miller’s father died, she was only 10 and they had to leave the castle. I was intrigued to learn from her bio that she lived in Newbury for a time. (Secondhand purchase – Barter Books) [98 pages]

Here and Now: Living in the Spirit by Henri J.M. Nouwen (1994)

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

This collection of micro-essays under themed headings like “Living in the Present” and “Suffering” was a perfect introduction to Nouwen’s life and theology. The Dutch Catholic priest lived in an Ontario community serving the physically and mentally disabled, and died of a heart attack just two years after this was published. I marked out many reassuring or thought-provoking passages. Here’s a good pre-Christmas one:

“God became a little child in the midst of a violent world. Are we surprised by joy or do we keep saying: ‘How nice and sweet, but the reality is different.’ What if the child reveals to us what is really real?”

I was taken by the ideas that the life of compassion is one of “downward mobility” and that inner freedom only comes when you don’t judge anyone. He encourages readers to not live in a past of shame and regret, but to be grateful for opportunities for God’s mercy and guidance. Very peaceful and readable; a good bedside devotional book. (Free from my stepfather) [175 pages]

De Profundis by Oscar Wilde (1897)

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

My only reread for the month. Wilde wrote this from prison. No doubt he had a miserable time there, but keeping in mind that he was a flamboyant dramatist and had an eye to this being published someday, this time around I found it more exaggerated and self-pitying than I had before. “Suffering is one very long moment. … Where there is sorrow there is holy ground,” he writes, stating that he has found “harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” He says he’s not going to try to defend his behaviour … but what is this but one extended apologia and humble brag, likening himself to a Greek tragic hero (“The gods had given me almost everything. But I let myself be lured into long spells of senseless and sensual ease. I amused myself with being a flâneur, a dandy, a man of fashion”) and even to Christ in his individuality as well as in his suffering at the hands of those who don’t understand him (the scene where he was pilloried consciously mimics a crucifixion tableau). As a literary document, it’s extraordinary, but I didn’t buy his sincerity. He feigns remorse but, really, wasn’t sorry about anything, merely sorry he got caught. (Free from a neighbour) [151 pages]

Original rating (2011):

Rating now:

Average:

Which of these have you read?

And which do you want to read? (You may choose no more than 4!)

In total, I read 27 novellas this November – close to my 2021 record of 29. The highlights included the Barton, Meier, Nouwen and Weingarten above plus Train Dreams by Denis Johnson and Western Lane by Chetna Maroo, but the best of the lot was Absolutely and Forever by Rose Tremain.

Coming right up, final statistics on the month’s participants and posts!

Short Stories in September, Part III: Butler, Costello, MacLaverty, Washington

Today I have a third set of terrific and varied short story collections. Between this, my Part I and Part II posts, and a bonus review I have coming up on Friday, I’ve gotten through 12 volumes of stories this month. This feels like a great showing for me because I don’t naturally gravitate to short stories and have to force myself to make a special effort to read them every September; otherwise, they tend to languish unread on my shelves and TBR.

From science fiction and horror tales set in alternate worlds to gritty slices of real life in Texas via two sets of quiet Irish relationship studies, this quartet of books showcases a range of tones and genres but fairly straightforward story structures and points of view. This was such a strong batch, I had to wonder why I never call myself a short story fan. All:

Bloodchild and Other Stories by Octavia E. Butler (2005)

My first R.I.P. selection and one I can heartily recommend – even if you’re normally wary of dystopias, horror and science fiction. Butler makes these genres accessible by peopling her plots with relatable protagonists and carefully accounting for their bizarre predicaments without wasting time on extraneous world-building. The way in which she explores very human issues alongside the existence of alien beings reminds me of Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, another of my rare forays into sci fi.

My first R.I.P. selection and one I can heartily recommend – even if you’re normally wary of dystopias, horror and science fiction. Butler makes these genres accessible by peopling her plots with relatable protagonists and carefully accounting for their bizarre predicaments without wasting time on extraneous world-building. The way in which she explores very human issues alongside the existence of alien beings reminds me of Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, another of my rare forays into sci fi.

Along with the original five stories Butler published in 1970s and 1980s magazines and anthologies, this second edition contains two essays on her writing process and two new stories that date to 2003. In “Bloodchild,” a small band of humans live on another planet ruled by the Tlic, which sound like giant spiders or scorpions. Gan learns he is expected to play his part by being a surrogate for T’Gatoi’s eggs, but is haunted by what he’s heard this process involves. In a brief afterword (one is included with each piece here), Butler explains that the story arose from her terror of botflies, which she knew she might encounter in the Peruvian Amazon, and that she has always faced what scares her through her writing.

My other favorite story was “The Evening and the Morning and the Night,” about a subclass of people afflicted with Duryea-Gode disease. A cruel side effect of a parent’s cancer treatment, the illness compels sufferers to self-harm and they are often confined to asylums. Lynn and Alan visit his mother in one such institution and see what their future might hold. “Speech Sounds” and “Amnesty” reminded me most of the Parable novels, with the latter’s Noah a leader figure similar to Lauren. After an apocalyptic event, people must adapt and cooperate to survive. I appreciated how the two essays value persistence – more so than talent or inspiration – as the key to success as a writer. This was my fourth book by Butler and I don’t see why I shouldn’t keep going and read her whole oeuvre. (University library)

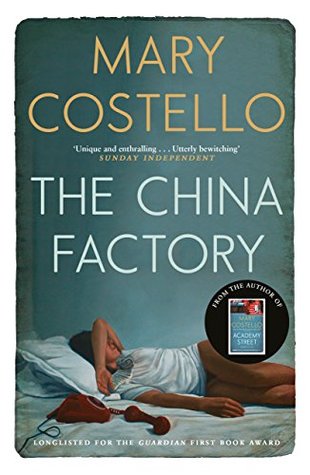

The China Factory by Mary Costello (2012)

Academy Street is a near-perfect novella and I also enjoyed The River Capture, so I wanted to complete the set by reading Costello’s first book. Its dozen understated stories are about Irish men and women the course of whose lives are altered by chance meetings, surprise liaisons, or not-quite-affairs that needle them ever after with the could-have-been. The mood of gentle melancholy would suit a chilly moonlight drive along the coast road to Howth. In the opening title story, a teenage girl rides to her work sponging clay cups with an oddball named Gus. Others can’t get past things like his body odour, but when there’s a crisis at the factory she sees his calm authority save the day. Elsewhere, a gardener rushes his employer to the hospital, a woman attends her ex-husband’s funeral, and a school inspector becomes obsessed with one of the young teachers he observes.

Academy Street is a near-perfect novella and I also enjoyed The River Capture, so I wanted to complete the set by reading Costello’s first book. Its dozen understated stories are about Irish men and women the course of whose lives are altered by chance meetings, surprise liaisons, or not-quite-affairs that needle them ever after with the could-have-been. The mood of gentle melancholy would suit a chilly moonlight drive along the coast road to Howth. In the opening title story, a teenage girl rides to her work sponging clay cups with an oddball named Gus. Others can’t get past things like his body odour, but when there’s a crisis at the factory she sees his calm authority save the day. Elsewhere, a gardener rushes his employer to the hospital, a woman attends her ex-husband’s funeral, and a school inspector becomes obsessed with one of the young teachers he observes.

Three favourites: In “And Who Will Pay Charon?” a man learns that, after he rejected Suzanne, she was hideously attacked in London. When she returns to the town as an old woman, he wonders what he might have done differently. “The Astral Plane” concerns a woman who strikes up a long-distance e-mail correspondence with a man from New York who picked up a book she left behind in a library. How will their intellectual affair translate into the corporeal world? The final story, “The Sewing Room,” reminded me most of Academy Street and could be a novel all of its own, as a schoolteacher and amateur fashion designer prepares for her retirement party and remembers the child she gave up for adoption. (Secondhand, gifted)

Blank Pages and Other Stories by Bernard MacLaverty (2021)

I knew from The Great Profundo that I liked MacLaverty’s stories, and I also enjoyed his latest novel, Midwinter Break, so I was delighted to hear news of a new collection. A number of the longer stories are set at turning points in twentieth-century history. In 1940, a mother is desperate to hear word of her soldier son; in 1971 Belfast, officers search a woman’s house. Two of the historical stories appealed to me for their medical elements: “The End of Days,” set in Vienna in 1918, dramatizes Egon Schiele’s fight with Spanish flu, while “Blackthorns” gives a lovely picture of how early antibiotics promoted miraculous recovery. In the title story, a cat is all a writer has left to remind him of his late wife. “Wandering” has a woman out looking for her dementia-addled mother. “The Dust Gatherer” muses on the fate of an old piano. Elderly parents and music recur, establishing filaments of thematic connection.

I knew from The Great Profundo that I liked MacLaverty’s stories, and I also enjoyed his latest novel, Midwinter Break, so I was delighted to hear news of a new collection. A number of the longer stories are set at turning points in twentieth-century history. In 1940, a mother is desperate to hear word of her soldier son; in 1971 Belfast, officers search a woman’s house. Two of the historical stories appealed to me for their medical elements: “The End of Days,” set in Vienna in 1918, dramatizes Egon Schiele’s fight with Spanish flu, while “Blackthorns” gives a lovely picture of how early antibiotics promoted miraculous recovery. In the title story, a cat is all a writer has left to remind him of his late wife. “Wandering” has a woman out looking for her dementia-addled mother. “The Dust Gatherer” muses on the fate of an old piano. Elderly parents and music recur, establishing filaments of thematic connection.

Three favourites: In “Glasshouses,” a man temporarily misplaces his grandchildren in the botanical gardens; “The Fairly Good Samaritan” is the fable of a jolly drunk who calls an ambulance for his poorly neighbour – but not before polishing off her brandy; and in the gorgeous “Sounds and Sweet Airs” a young woman’s harp music enthrals the passengers on a ferry.

With thanks to Jonathan Cape for the free copy for review.

Lot: Stories by Bryan Washington (2019)

The musical equivalent of Lot might be a mixtape played on a boombox or blasted from an open-top Corvette while touring the streets of Houston, Texas. Most of this Dylan Thomas Prize-winning linked collection follows Nic, a mixed-race Black/Latino boy who works in the family restaurant. As his family situation realigns – his father leaves, his older brother Javi enlists, his sister Jan has a baby – he’s trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and wondering if this gentrifying city suits him anymore. But he knows he’ll take himself wherever he goes, and as the book closes with “Elgin” (the most similar in mood and setup to Washington’s debut novel, Memorial) he’s thinking of taking a chance on love.

The musical equivalent of Lot might be a mixtape played on a boombox or blasted from an open-top Corvette while touring the streets of Houston, Texas. Most of this Dylan Thomas Prize-winning linked collection follows Nic, a mixed-race Black/Latino boy who works in the family restaurant. As his family situation realigns – his father leaves, his older brother Javi enlists, his sister Jan has a baby – he’s trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and wondering if this gentrifying city suits him anymore. But he knows he’ll take himself wherever he goes, and as the book closes with “Elgin” (the most similar in mood and setup to Washington’s debut novel, Memorial) he’s thinking of taking a chance on love.

Drug dealers, careworn immigrants and prostitutes: Even the toughest guys have tender hearts in these stories. Eleven of 13 stories are in the first person. Where the narration isn’t Nic’s, it’s usually the collective voice of the neighbourhood boys. As far as I can tell, most of the story titles refer to Houston sites: particular addresses or neighbourhoods, or more vague locations. Like in Memorial, there are no speech marks. Washington’s prose is earthy and slang-filled. The matter-of-fact phrasing made me laugh: “He knocked her up in the usual way. For six minutes it looked like he’d stick around”; “He’d been staying there since the Great Thanksgiving Rupture, back when his brother’d found the dick pic in his pillowcase.” With the melting pot of cultures, the restaurant setting, and the sharp humour, this reminded me of Elaine Castillo’s America Is Not the Heart.

Three favourites: In “Shepherd,” the narrator emulates a glamorous cousin from Jamaica; “Bayou” is completely different from the rest, telling the urban legend of a “chupacubra” (a mythical creature like a coyote); “Waugh,” the longest story and one of just two told in the third person, is about a brothel’s worth of male sex workers and their pimp. Its final page is devastating. Despite their bravado, Washington’s characters are as vulnerable as Brandon Taylor’s. I think of these two young gay African American writers as being similar at root even though their style and approach are so very different. (New purchase)

A side note: I’m wondering how an author chooses primarily first person or third person POVs for short stories. MacLaverty and Taylor write exclusively in an omniscient third person; Washington and Eley Williams almost always plump for the first person. (Here, Butler was about half and half and Costello only used first person in three stories.) Is the third person seen as more impartial and commanding – a more elevated form of fiction? Is first person more immediate, informal and natural, but also perhaps too easy? I wouldn’t say I prefer one or the other (not in my novels, either); it all depends on the execution. Notably, none of this year’s stories were in the second person or employed experimental structures.

Two more collections I’m reading are spilling across into October for R.I.P., but will I keep up the short story habit after that? I still have a shelf full of unread story collections, and I have my eye on My Monticello, which I got from NetGalley…