R.I.P., Part II: Duy Đoàn, T. Kingfisher & Rachael Smith

A second installment for the Readers Imbibing Peril challenge (first was a creepy short story collection). Zombies link my first two selections, an experimental poetry collection and a historical novella that updates a classic, followed by a YA graphic novel about a medieval witch who appears in contemporary life to help a teen deal with her problems. I don’t really do proper horror; I’d characterize all three of these as more mischievous than scary.

Zombie Vomit Mad Libs by Duy Đoàn

The Vietnamese American poet’s second collection strikes a balance between morbid – a pair of sonnets chants the names and years of poets who died by suicide – and playful. Multiple poems titled “Zombie” or “Zombies” are composed of just 1–3 cryptic lines. Other repeated features are blow-by-blow descriptions of horror movie scenes and the fill-in-the-blank Mad Libs format. There is an obsession with Leslie Cheung, a gay Hong Kong actor who also died by suicide, in 2003. Đoàn experiments linguistically as well as thematically, by adding tones (as used in Vietnamese) to English words. This was a startling collection I admired for its range and pluck, though I found little to personally latch on to. I was probably expecting something more like 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le. But if you think poetry can’t get better than zombies + linguistics + suicides, boy have I got the collection for you! (Đoàn’s first book, We Play a Game, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and a Lambda Literary Award for bisexual poetry.)

The Vietnamese American poet’s second collection strikes a balance between morbid – a pair of sonnets chants the names and years of poets who died by suicide – and playful. Multiple poems titled “Zombie” or “Zombies” are composed of just 1–3 cryptic lines. Other repeated features are blow-by-blow descriptions of horror movie scenes and the fill-in-the-blank Mad Libs format. There is an obsession with Leslie Cheung, a gay Hong Kong actor who also died by suicide, in 2003. Đoàn experiments linguistically as well as thematically, by adding tones (as used in Vietnamese) to English words. This was a startling collection I admired for its range and pluck, though I found little to personally latch on to. I was probably expecting something more like 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem by Nam Le. But if you think poetry can’t get better than zombies + linguistics + suicides, boy have I got the collection for you! (Đoàn’s first book, We Play a Game, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and a Lambda Literary Award for bisexual poetry.)

To be published in the USA by Alice James Books on November 12. With thanks to the publisher for the advanced e-copy for review.

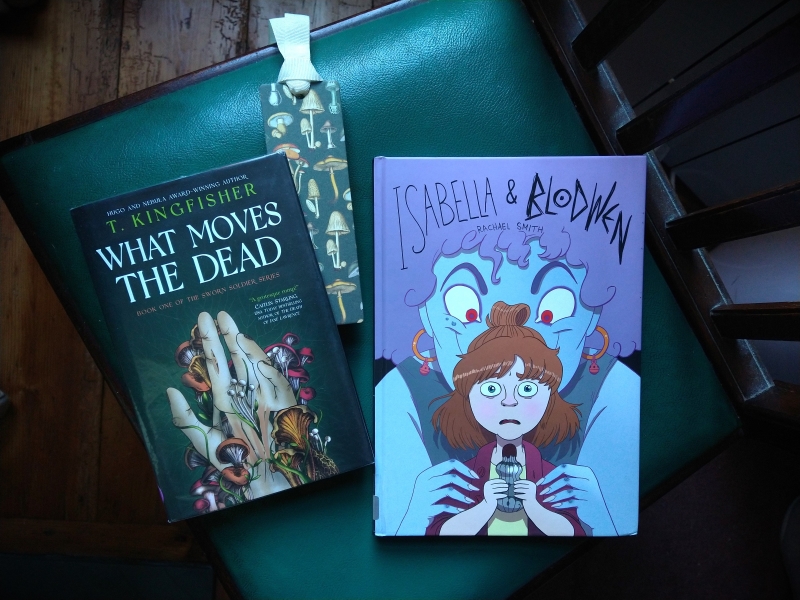

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher (2022)

{MILD SPOILERS AHEAD}

This first book in the “Sworn Soldier” duology is a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Set in the 1890s, it’s narrated by Alex Easton, a former Gallacian soldier who learns that their childhood friend Madeline Usher is dying and goes to visit her at her and her brother Roderick’s home in Ruritania. Easton also meets the Ushers’ friend, the American doctor Denton, and Eugenia Potter, an amateur mycologist (and aunt of a certain Beatrix). Easton and Potter work out that what is making Madeline ill is the same thing that’s turning the local rabbits into zombies…

This first book in the “Sworn Soldier” duology is a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Set in the 1890s, it’s narrated by Alex Easton, a former Gallacian soldier who learns that their childhood friend Madeline Usher is dying and goes to visit her at her and her brother Roderick’s home in Ruritania. Easton also meets the Ushers’ friend, the American doctor Denton, and Eugenia Potter, an amateur mycologist (and aunt of a certain Beatrix). Easton and Potter work out that what is making Madeline ill is the same thing that’s turning the local rabbits into zombies…

At first it seemed the author was awkwardly inserting a nonbinary character into history, but it’s more complicated than that. The sworn soldier tradition in countries such as Albania was a way for women, especially orphans or those who didn’t have brothers to advocate for them, to have autonomy in martial, patriarchal cultures. Kingfisher makes up European nations and their languages, as well as special sets of pronouns to refer to soldiers (ka/kan), children (va/van), etc. She doesn’t belabour the world-building, just sketches in the bits needed.

This was a quick and reasonably engaging read, though I wasn’t always amused by Kingfisher’s gleefully anachronistic tone (“Mozart? Beethoven? Why are you asking me? It was music, it went dun-dun-dun-DUN, what more do you want me to say?”). I wondered if the plot might have been inspired by a detail in Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, but it seems more likely it’s a half-conscious addition to a body of malevolent-mushroom stories (Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia, various by Jeff VanderMeer, The Beauty by Aliya Whiteley). I was drawn in by Easton’s voice and backstory enough to borrow the sequel, about which more anon. (T. Kingfisher is the pen name of Ursula Vernon.) (Public library)

Isabella & Blodwen by Rachael Smith (2023)

I’d reviewed Smith’s adult graphic memoirs Quarantine Comix (mental health during Covid) and Glass Half Empty (alcoholism and bereavement) for Foreword and Shelf Awareness, respectively. When I spotted this in the Young Adult section and saw it was about a witch, I mentally earmarked it for R.I.P. Isabella Maria Penwick-Wickam is a precocious 16-year-old student at Oxford. With her fixation on medieval history and folklore, she has the academic side of the university experience under control. But her social life is hopeless. She’s alienated flatmates and classmates alike with her rigid habits and judgemental comments. On a field trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum, where students are given a rare opportunity to handle artefacts, she accidentally drops a silver bottle into her handbag. Before she can return it, its occupant, a genie-like blowsy blue-and-purple witch named Blodwen, is released into the world. She wreaks much merry havoc, encouraging Issy to have some fun and make friends.

I’d reviewed Smith’s adult graphic memoirs Quarantine Comix (mental health during Covid) and Glass Half Empty (alcoholism and bereavement) for Foreword and Shelf Awareness, respectively. When I spotted this in the Young Adult section and saw it was about a witch, I mentally earmarked it for R.I.P. Isabella Maria Penwick-Wickam is a precocious 16-year-old student at Oxford. With her fixation on medieval history and folklore, she has the academic side of the university experience under control. But her social life is hopeless. She’s alienated flatmates and classmates alike with her rigid habits and judgemental comments. On a field trip to the Pitt Rivers Museum, where students are given a rare opportunity to handle artefacts, she accidentally drops a silver bottle into her handbag. Before she can return it, its occupant, a genie-like blowsy blue-and-purple witch named Blodwen, is released into the world. She wreaks much merry havoc, encouraging Issy to have some fun and make friends.

It’s a sweet enough story, but a few issues detracted from my enjoyment. Issy is often depicted more like a ten-year-old. I don’t love the blocky and exaggerated features Smith gives her characters, or the Technicolor hues. And I found myself rolling my eyes at how the book unnaturally inserts a sexual harassment theme – which Blodwen responds to in modern English, having spoken in archaic fashion up to that point, and with full understanding of the issue of consent. I can imagine younger teens enjoying this, though. (Public library)

The mini playlist I had going through my mind as I wrote this:

- “Running with Zombies” by The Bookshop Band (inspired by The Making of Zombie Wars by Aleksandar Hemon)

- “Flesh and Blood Dance” by Duke Special

- “Dead Alive” by The Shins

And to counterbalance the evil fungi of the Kingfisher novella, here’s Anne-Marie Sanderson employing the line “A mycelium network is listening to you” in a totally non-threatening way. It’s one of the multiple expressions of reassurance in her lovely song “All Your Atoms,” my current earworm from her terrific new album Old Light.

20 Books of Summer, 11–13: Campbell, Julavits, Lu

Two solid servings of women’s life writing plus a novel about a Chinese woman stuck in roles she’s not sure she wants anymore.

Thunderstone: A true story of losing one home and discovering another by Nancy Campbell (2022)

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

The title refers to a fossil that has been considered a talisman in various cultures, and she needed the good luck during a period that involved accidental carbon monoxide poisoning and surgery for an ovarian abnormality (but it didn’t protect her books, which were all destroyed in a leaking shipping container – the horror!). I most enjoyed the longer entries where she muses on “All the potential lives I moved on from” during 20 years in Oxford and elsewhere, which makes me think that I would have preferred a more traditional memoir by her. Covid narratives feel really dated now, unfortunately. (New (bargain) purchase from Hungerford Bookshop with birthday voucher)

Directions to Myself: A Memoir by Heidi Julavits (2023)

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Mostly the memoir takes readers through everyday conversations the author has with friends and family about situations of inequality or harassment. Through her words she tries to gently steer her son towards more open-minded ideas about gender roles. She also entrances him and his sleepover friends with a real-life horror story about being chased through the French countryside by a man in a car. The tenor of her musings appealed to me, but already the details are fading. I suspect this will mean much more to a parent.

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free copy for review.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu (2023)

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy.

August Releases: Bright Fear, Uprooting, The Farmer’s Wife, Windswept

This month I have three memoirs by women, all based on a connection to land – whether gardening, farming or crofting – and a sophomore poetry collection that engages with themes of pandemic anxiety as well as crossing cultural and gender boundaries.

My August highlight:

Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan

Chan’s Flèche was my favourite poetry collection of 2019. Their follow-up returns to many of the same foundational subjects: race, family, language and sexuality. But this time, the pandemic is a lens through which all is filtered. This is particularly evident in Part I, “Grief Lessons.” “London, 2020” and “Hong Kong, 2003,” on facing pages, contrast Covid-19 with SARS, the major threat when they were a teenager. People have always made assumptions about them based on their appearance or speech. At a time when Asian heritage merited extra suspicion, English was both a means of frank expression and a source of ambivalence:

“At times, English feels like the best kind of evening light. On other days, English becomes something harder, like a white shield.” (from “In the Beginning Was the Word”)

“my Chinese / face struck like the glow of a torch on a white question: / why is your English so good, the compliment uncertain / of itself.” (from “Sestina”)

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

At the centre of the book, “Ars Poetica,” a multi-part collage incorporating lines from other poets, forms a kind of autobiography in verse. Chan also questions the lines between genres, wondering whether to label their work poetry, nonfiction or fiction (“The novel feels like a springer spaniel running off-/leash the poem a warm basket it returns to always”).

The poems’ structure varies, with paragraphs and stanzas of different lengths and placement on the page (including, in one instance, a goblet shape). The enjambment, as you can see in lines I’ve quoted above and below, is noteworthy. Part III, “Field Notes on a Family,” reflects on the pressures of being an only child whose mother would prefer to pretend lives alone rather than with a female partner. The book ends with hope that Chan might be able to be open about their identity. The title references the paradoxical nature of the sublime, beautifully captured via the alliteration that closes “Circles”: “a commotion of coots convincing / me to withstand the quotidian tug-/of-war between terror and love.”

Although Flèche still has the edge for me, this is another excellent work I would recommend even to those wary of poetry.

Some more favourite lines, from “Ars Poetica”:

“What my mother taught me was how

to revere the light language emitted.”

“Home, my therapist suggests, is where

you don’t have to explain yourself.”

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Three land-based memoirs:

(All:  )

)

Uprooting: From the Caribbean to the Countryside – Finding Home in an English Country Garden by Marchelle Farrell

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

This Nan Shepherd Prize-winning memoir shares Chan’s attention to pandemic-era restrictions and how they prompt ruminations about identity and belonging. Farrell is from Trinidad but came to the UK as a student and has stayed, working as a psychiatrist and then becoming a wife and mother. Just before Covid hit, she moved to the outskirts of Bath and started rejuvenating her home’s large and neglected garden. Under thematic headings that also correspond to the four seasons, chapters are named after different plants she discovered or deliberately cultivated. The peace she finds in her garden helps her to preserve her mental health even though, with the deaths of George Floyd and so many other Black people, she is always painfully aware of her fragile status as a woman of colour, and sometimes feels trapped in the confining routines of homeschooling. I enjoyed the exploration of postcolonial family history and the descriptions of landscapes large and small but often found Farrell’s metaphors and psychological connections obvious or strained.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Farmer’s Wife: My Life in Days by Helen Rebanks

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

I fancied a sideways look at James Rebanks (The Shepherd’s Life and Wainwright Prize winner English Pastoral) and his regenerative farming project in the Lake District. (My husband spotted their dale from a mountaintop on holiday earlier in the month.) Helen Rebanks is a third-generation farmer’s wife and food and family are the most important things to her. One gets the sense that she has felt looked down on for only ever wanting to be a wife and mother. Her memoir, its recollections structured to metaphorically fall into a typical day, is primarily a defence of the life she has chosen, and secondarily a recipe-stuffed manifesto for eating simple, quality home cooking. (She paints processed food as the enemy.)

Growing up, Rebanks started cooking for her family early on, and got a job in a café as a teenager; her mother ran their farm home as a B&B but was forgetful to the point of being neglectful. She met James at 17 and accompanied him to Oxford, where they must have been the only student couple cooking and eating proper food. This period, when she was working an office job, baking cakes for a café, and mourning the devastating foot-and-mouth disease epidemic from a distance, is most memorable. Stories from travels, her wedding, and the births of her four children are pleasant enough, yet there’s nothing to make these experiences, or the telling of them, stand out. I wouldn’t make any of the dishes; most you could find a recipe for anywhere. Eleanor Crow’s black-and-white illustrations are lovely, though.

With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review.

Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands by Annie Worsley

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

I’d come across Worsley in the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies. For a decade she has lived on Red River Croft, in a little-known pocket of northwest Scotland. In word pictures as much as in the colour photographs that illustrate this volume, she depicts it as a wild land shaped mostly by natural forces – also, sometimes, manmade. From one September to the next, she documents wildlife spectacles and the influence of weather patterns. Chronic illness sometimes limited her daily walks to the fence at the cliff-top. (But what a view from there!) There is more here about local history and ecology than any but the keenest Scotland-phile may be interested to read. Worsley also touches on her upbringing in polluted Lancashire, and her former academic career and fieldwork in Papua New Guinea. Her descriptions are full of colours and alliteration, though perhaps a little wordy: “Pale-gold autumnal days are spliced by fickle and feisty bouts of turbulent weather. … Sunrises and sunsets may pour with cinnabar and henna; dawn and dusk can ripple with crimson and purple.” The kind of writing I could appreciate for the length of an essay but not a whole book.

With thanks to William Collins for the free copy for review.

Would you read one or more of these?

Recent BookBrowse & Shiny New Books Reviews, and Book Club Ado

Excerpts from and links to some of my recent online writing for other places:

BookBrowse

Three O’Clock in the Morning by Gianrico Carofiglio

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The quotation that gives Carofiglio’s tender novel its title is from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up: “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” It lends an appropriate sense of time suspended, of earnest seeking and extreme circumstances: The main action of the book takes place over just a few days in June of 1983, when Italian teenager Antonio and his father are stranded in Marseilles while there for Antonio to be seen by an epilepsy specialist. The gift of this time outside of time allows them to get to know each other better, such that the memory of the trip will be precious to Antonio even decades later. I appreciated how the limited setting heightened this short novel’s emotions. Carofiglio invites readers to peer between the leisurely progression of events to see the bond that is being formed. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my related article on HarperVia, a new publishing imprint for international literature.)

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Inspired by the composition of the Oxford English Dictionary, this Australian debut novel explores the lives of the women on its fringes through the words that were omitted. The suffrage movement and World War I loom large as the storyline enters the 1910s. I most appreciated the relationships Esme has with the various women in her life. The main action spans the 40 years of the original composition of the OED. That scope means there is a lot of skipping forward in time. Especially in the first half, I longed for the narrative to slow down so I could spend more time with this character. Despite the first-person narration, I never felt I knew Esme very well. Women’s bonds and women’s words are strong themes in this forthrightly feminist novel that, despite its flaws, would make a great book club selection. (See my full review at BookBrowse. See also my reading list of books about dictionaries and lost words.)

Shiny New Books

Notes from Deep Time: The Hidden Stories of the Earth Beneath Our Feet by Helen Gordon

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

To assess the place of humanity, we can look back to prehistory, but also forward to envision the “deep future.” (It was only in a late chapter on nuclear waste disposal sites and warning messages to the future that I found too much direct overlap with Footprints by David Farrier.) This engagingly blends both tactics, surveying the fields of geology and palaeontology and pondering the future traces of the Anthropocene. I most enjoyed the middle chapters, in which science meets wildlife and cultural studies. For instance, a chapter on ammonites leads into a profile of Mary Anning and the history of both fossil hunting and women in STEM careers. The prose is well pitched to the layman’s level. Interviews, travels, and snapshots from her own life generally keep the material from becoming too dry. An invigorating interdisciplinary tour. (See my full review at Shiny New Books.)

My book club has been meeting via Zoom since April 2020. This is a common state of affairs for book clubs around the world. Especially since we have 12 members (if everyone attends, which is rare), we haven’t been able to contemplate meeting in person as of yet. However, a subset of us meet midway between the monthly reads to discuss women’s classics like Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. For next week’s meeting on Mrs. Dalloway, we are going to attempt a six-person get-together in one member’s house.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

Anyway, a neat thing we did last month was a Zoom chat with the author: a BBC correspondent who happens to be the brother of one of our members. If you’re a news junkie in the UK, you may know the name Jon Sopel, though since I don’t have a telly or ever listen to radio, I hadn’t encountered him until this “in-person” meet-up. He has been the BBC’s North America Editor since 2014.

UnPresidented is the third book he wrote over the course of the Trump presidency. It started off as a diary of the 2020 election campaign, beginning in July 2019, but of course soon morphed into something slightly different: a chronicle of life in D.C. and London during Covid-19 and a record of the Trump mishandling of the pandemic. But as well as a farcical election process and a public health crisis, 2020’s perfect storm also included economic collapse and social upheaval – thanks to the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests worldwide plus isolated rioting.

UnPresidented served as a good reminder for me of the timeline of events and the full catalogue of outrages committed by Trump and his cronies. You just have to shake your head over the litany of ridiculous things he said and did, and got away with – any one of which might have sunk another president or candidate. The style is breezy and off-the-cuff, so the book reads quickly. There’s a good balance between world events and personal ones, with his family split across the UK and Australia. I appreciated the insight into differences from the British system. I thought it would be depressing reading back through the events of 2020, but for the most part the knowledge that everything turned out “right” allowed me to see the humour in it. Still, I found it excruciating reading about the four days following the election.

Sopel kindly gave us an hour of his time one Wednesday evening before he had to go on air and answered our questions about Biden, Harris, journalistic ethics, and more. He was charming and eloquent, as befits his profession.

Would any of these books interest you?

Another Birthday & An “Overhaul” of Previous Years’ Gifted Books

I thought a Wednesday would be a crummy day to have a birthday on, but actually it was great – the celebrations have extended from the weekend before to the weekend after, giving me a whole week of treats. Last Saturday we planned a last-minute trip to Oxford when I won a pair of free tickets to the Oxford Playhouse’s comedy club, their first live event since March. It featured three acts plus a compere and was headlined by Flo & Joan, a musical sister act we’d seen before at Greenbelt 2018. Beforehand, we had excellent pizzas at Franco Manca. Oxford felt busy, but we wore masks to queue at the restaurant and for the whole time in the Playhouse, where there were several seats left between parties plus every other row was empty.

My husband was able to work from home on the day itself, even though he’s been having a manically busy couple of weeks of in-person teaching and labs on campus, so we got to share a few meals: a leisurely pancake breakfast; fresh-baked maple, walnut and pear upside-down cake, a David Lebovitz recipe from Ready for Dessert (recreated here); and a French-influenced dinner at The Blackbird, a local pub we’d not tried before. In between I did some reading (of course), helped hunt in the garden for invertebrates for the labs, and did a video chat with my mom and sister in the States.

Today, since he had a bit more time free, he has made me Mexican food, one of my favorite cuisines and something I don’t get to have very often, plus a second cake from a Lebovitz recipe (luckily, the remnants of the last one had already gone in the freezer), this time a flourless chocolate cake topped with cacao nibs.

Just three books came in as gifts this year, though I might buy a few more with birthday money and vouchers. (A proof copy of Claire Fuller’s new novel, forthcoming in January, happened to arrive on my birthday, so I’ll call that four books as presents!) I also received chocolate, posh local drink, and the latest Alanis album.

An Overhaul of Previous Years’ Gifted Books

For a bit of fun, I thought I’d go back through the previous birthday book hauls I’ve posted about and see how many of the books I’ve read: 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019.

Simon of Stuck in a Book runs a regular blog feature he calls “The Overhaul,” where he revisits a book haul from some time ago and takes stock of what he’s read, what he still owns, etc. (here’s the most recent one). With permission, I’ve borrowed the title and format.

Date of haul: October 2015

Number of books purchased: 7 [the bottom 3 pictured were bought for other people]

Had already read: 2 (the Byatt story collections, one of which I reread earlier this year)

Read since: 2 (reviews of the Jerome and Zola appeared on the blog)

Still to read: 3 – It’s high time I got around to the Byron and Dinesen books after five years sat on my shelves! I DNFed the first Gormenghast book, though, so may end up jettisoning the whole trilogy.

Date of haul: October 2016

Number of books purchased/received: 6

Read: ALL 6! I am so proud about this. Reviews of the Brown, Taylor, and Welch have appeared on the blog.

Still own: Just 2 – I resold the Brown and Holloway after reading them, gave the Mercer to a friend, and donated the Taylor proof.

Date of haul: October 2017

Number of books received: 11

Read: 4 (reviews of the Cox, Hay, and Hoffman appeared on the blog)

DNFed and resold: 2

Still to read: 5

Date of haul: October 2018

Number of books received: 10

Read: 8! Another fine showing; only the Giffels and Winner remain to be read. Reviews of the Groff, one L’Engle, and Manyika & Richardson appeared on the blog.

Still own: 8 – I resold the Hood and Petit after reading them.

Date of haul: October 2019

Number of books received: 14

Read: Only 2. Hmm. (I reviewed the Weiss, and the Houston appeared on my Best of 2019 runners-up list.)

Currently reading/skimming, or set aside temporarily: 4

DNFed and resold: 3. D’oh.

Still to read: 5

Are you good about reading gifted books quickly?

What catches your eye from my stacks?

Four February Releases: Napolitano, Offill, Smyth, Sprackland

Much as I’d like to review books in advance of their release dates, that doesn’t seem to be how things are going this year. I hope readers will find it useful to learn about recent releases they might have missed. This month I’m featuring a post-plane crash scenario, a reflection on modern anxieties, an essay about the human–birds relationship, and a meditation on graveyards.

Dear Edward by Ann Napolitano

(Published by Penguin/Viking on the 20th; came out in USA from Dial Press last month)

June 2013: a plane leaves Newark Airport for Los Angeles, carrying 192 passengers. Five hours after takeoff, it crashes in the flatlands of northern Colorado, a victim to stormy weather and pilot error. Only 12-year-old Edward Adler is found alive in the wreckage. In alternating storylines, Napolitano follows a select set of passengers (the relocating Adler family, an ailing tycoon, a Wall Street playboy, an Afghanistan veteran, a Filipina clairvoyant, a pregnant woman visiting her boyfriend) in their final hours, probing their backstories to give their soon-to-end lives context (and meaning?), and traces the first six years of the crash’s aftermath for Edward.

June 2013: a plane leaves Newark Airport for Los Angeles, carrying 192 passengers. Five hours after takeoff, it crashes in the flatlands of northern Colorado, a victim to stormy weather and pilot error. Only 12-year-old Edward Adler is found alive in the wreckage. In alternating storylines, Napolitano follows a select set of passengers (the relocating Adler family, an ailing tycoon, a Wall Street playboy, an Afghanistan veteran, a Filipina clairvoyant, a pregnant woman visiting her boyfriend) in their final hours, probing their backstories to give their soon-to-end lives context (and meaning?), and traces the first six years of the crash’s aftermath for Edward.

While this is an expansive and compassionate novel that takes seriously the effects of trauma and the difficulty of accepting random suffering, I found that I dreaded returning to the plane every other chapter – I have to take regular long-haul flights to see my family, and while I don’t fear flying, I also don’t need anything that elicits catastrophist thinking. I would read something else by Napolitano (she’s written a novel about Flannery O’Connor, for instance), but I can’t imagine ever wanting to open this up again.

I picked up a proof copy at a Penguin Influencers event.

Weather by Jenny Offill

(Published by Knopf [USA] on the 11th and Granta [UK] on the 13th)

Could there be a more perfect book for 2020? A blunt, unromanticized but wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, Weather is written in the same aphoristic style as Offill’s Dept. of Speculation but has a more substantial story to tell. Lizzie Benson is married with a young son and works in a New York City university library. She takes on an informal second job as PA to Sylvia, her former professor, who runs a podcast on environmental issues and travels to speaking engagements.

Could there be a more perfect book for 2020? A blunt, unromanticized but wickedly funny novel about how eco-anxiety permeates everyday life, Weather is written in the same aphoristic style as Offill’s Dept. of Speculation but has a more substantial story to tell. Lizzie Benson is married with a young son and works in a New York City university library. She takes on an informal second job as PA to Sylvia, her former professor, who runs a podcast on environmental issues and travels to speaking engagements.

Set either side of Trump’s election, the novel amplifies many voices prophesying doom, from environmentalists to Bible-thumpers (like Lizzie’s mother) to those who aren’t sure they’ll even make it past tomorrow (like her brother, a highly unstable ex-addict who’s having a baby with his girlfriend). It’s a wonder it doesn’t end up feeling depressing. Lizzie’s sardonic narration is an ideal way of capturing relatable feelings of anger and helplessness, cringing fear and desperate hope. Don’t expect to come away with your worries soothed, though there is some comfort to be found in the feeling that we’re all in this together.

Favorite lines:

“Young person worry: What if nothing I do matters? Old person worry: What if everything I do does?”

“Once sadness was considered one of the deadly sins, but this was later changed to sloth. (Two strikes then.)”

“My husband is reading the Stoics before breakfast. That can’t be good, can it?”

I read an e-ARC via Edelweiss.

An Indifference of Birds by Richard Smyth

(Published by Uniformbooks on the 14th)

Birds have witnessed the whole of human history, sometimes profiting from our behavior – our waste products provide them with food, our buildings can be handy nesting and hunting platforms, and our unintentional wastelands and demilitarized zones turn into nature reserves – but more often suffering incidental damage. That’s not even considering our misguided species introductions and the extinctions we’ve precipitated. Eighty percent of bird species are now endangered. For as minimal as the human fossil record will be, we have a lot to answer for.

Birds have witnessed the whole of human history, sometimes profiting from our behavior – our waste products provide them with food, our buildings can be handy nesting and hunting platforms, and our unintentional wastelands and demilitarized zones turn into nature reserves – but more often suffering incidental damage. That’s not even considering our misguided species introductions and the extinctions we’ve precipitated. Eighty percent of bird species are now endangered. For as minimal as the human fossil record will be, we have a lot to answer for.

From past to future, archaeology to reintroduction and de-extinction projects, this is a wide-ranging essay that still comes in at under 100 pages. It’s a valuable shift in perspective from human-centric to bird’s-eye view. The prose is not at all what I’ve come to expect from nature writing (earnest, deliberately lyrical); it’s more rhetorical and inventive, a bit arch but still passionate – David Foster Wallace meets Virginia Woolf? The last six paragraphs, especially, soar into sublimity. A niche book, but definitely recommended for bird-lovers.

Favorite lines:

“They must see us, watch us, from the same calculating perspective as they did two million years ago. We’re still galumphing heavy-footed through the edgelands, causing havoc, small life scattering wherever we tread.”

“Wild things lease these places from a capricious landlord. They’re yours, we say, until we need them back.”

I pre-ordered my copy directly from the publisher.

These Silent Mansions: A life in graveyards by Jean Sprackland

(Published by Jonathan Cape on the 6th)

I’m a big fan of Sprackland’s beachcombing memoir, Strands, and have also read some of her poetry. Familiarity with her previous work plus a love for graveyards induced me to request a copy of her new book. In it she returns to the towns and cities she has known, wanders through their graveyards, and researches and imagines her way into the stories of the dead. For instance, she finds the secret burial place of persecuted Catholics in Lancashire, learns about a wrecked slave ship in a Devon cove, and laments two dead children whose bodies were sold for dissections in 1890s Oxford. She also remarks on the shifts in her own life, including the fact that she now attends more funerals than weddings, and the displacement involved in cremation – there is no site she can visit to commune with her late mother.

I’m a big fan of Sprackland’s beachcombing memoir, Strands, and have also read some of her poetry. Familiarity with her previous work plus a love for graveyards induced me to request a copy of her new book. In it she returns to the towns and cities she has known, wanders through their graveyards, and researches and imagines her way into the stories of the dead. For instance, she finds the secret burial place of persecuted Catholics in Lancashire, learns about a wrecked slave ship in a Devon cove, and laments two dead children whose bodies were sold for dissections in 1890s Oxford. She also remarks on the shifts in her own life, including the fact that she now attends more funerals than weddings, and the displacement involved in cremation – there is no site she can visit to commune with her late mother.

I most enjoyed the book’s general observations: granite is the most prized headstone material, most graves go unvisited after 15 years, and a third of Britons believe in angels despite the country’s overall decline in religious belief. I also liked Sprackland’s list of graveyard charms she has seen. While I applaud any book that aims to get people thinking and talking about death, I got rather lost in the historical particulars of this one.

Favorite lines:

“This is the paradox at the heart of our human efforts to remember and memorialise: the wish to last forever, and the knowledge that we are doomed to fail.”

“Life, under such a conscious effort of remembering, sometimes resembles a series of clumsy jump-cuts rather than one continuous narrative.”

My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury)

The Museum of Whales You Will Never See: Travels among the Collectors of Iceland by A. Kendra Greene (2020) – This sounded quirky and fun, but it turns out it was too niche for me. I read the first two “Galleries” (78 pp.) about the Icelandic Phallological Museum and one woman’s stone collection. Another writer might have used a penis museum as an excuse for lots of cheap laughs, but Greene doesn’t succumb. Still, “no matter how erudite or innocent you imagine yourself to be, you will discover that everything is funnier when you talk about a penis museum. … It’s not salacious. It’s not even funny, except that the joke is on you.” I think I might have preferred a zany Sarah Vowell approach to the material. (Secondhand – Bas Books and Home, Newbury) Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library)

Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long (2023) – A free signed copy – and, if I’m honest, a cover reminiscent of Ned Beauman’s Glow – induced me to try an author I’d never heard of. She’s a stand-up comic, apparently, not that you’d know it from these utterly boring, one-note stories about unhappy adolescents and mums on London council estates. I read 108 pages but could barely tell you what a single story was about. Long is decent at voices, but you need compelling stories to house them. (Little Free Library) Ante remembers the years when her mother was absent but promised to send for the rest of the family soon: “You said all I needed to do was to sleep and before I knew it, / you’d be back. But I woke to the rice that needed rinsing, / my siblings’ school uniforms that needed ironing.” The medical profession as a family legacy and noble calling is a strong element of these poems, especially in “Invisible Women,” an ode to the “goddesses of caring and tending” who walk the halls of any hospital. Hard work is a matter of survival, and family – whether physically present or not – bolsters weary souls. A series of short, untitled poems are presented as tape recordings made for her mother.

Ante remembers the years when her mother was absent but promised to send for the rest of the family soon: “You said all I needed to do was to sleep and before I knew it, / you’d be back. But I woke to the rice that needed rinsing, / my siblings’ school uniforms that needed ironing.” The medical profession as a family legacy and noble calling is a strong element of these poems, especially in “Invisible Women,” an ode to the “goddesses of caring and tending” who walk the halls of any hospital. Hard work is a matter of survival, and family – whether physically present or not – bolsters weary souls. A series of short, untitled poems are presented as tape recordings made for her mother. In “Happily Ever After,” Lyssa works in the gift shop of a Titanic replica and is cast as an extra in a pop star’s music video. Mythical sea monsters are contrasted with the real dangers of her life, like cancer and racism. “Anything Could Disappear” was a favourite of mine, though it begins with that unlikely scenario of a single woman acquiring a baby as if by magic. What starts off as a burden becomes a bond she can’t bear to let go. A family is determined to clear the name of their falsely imprisoned ancestor in “Alcatraz.” In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” (a mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow), photojournalist Rena is wary about attending the wedding of a friend she met when their plane was detained in Africa some years ago. The only wedding she’s been in is her sister’s, which ended badly.

In “Happily Ever After,” Lyssa works in the gift shop of a Titanic replica and is cast as an extra in a pop star’s music video. Mythical sea monsters are contrasted with the real dangers of her life, like cancer and racism. “Anything Could Disappear” was a favourite of mine, though it begins with that unlikely scenario of a single woman acquiring a baby as if by magic. What starts off as a burden becomes a bond she can’t bear to let go. A family is determined to clear the name of their falsely imprisoned ancestor in “Alcatraz.” In “Richard of York Gave Battle in Vain” (a mnemonic for the colours of the rainbow), photojournalist Rena is wary about attending the wedding of a friend she met when their plane was detained in Africa some years ago. The only wedding she’s been in is her sister’s, which ended badly. The obsession began when he was eight years old and someone brought him a dead swift fledgling for his taxidermy hobby. Ever since, he’s dated the summer by their arrival. “It is always summer for them,” though, as his opening line has it. This monograph is structured chronologically. Much like Tim Dee does in

The obsession began when he was eight years old and someone brought him a dead swift fledgling for his taxidermy hobby. Ever since, he’s dated the summer by their arrival. “It is always summer for them,” though, as his opening line has it. This monograph is structured chronologically. Much like Tim Dee does in  As I’ve found with a number of Little Toller releases now (On Silbury Hill,

As I’ve found with a number of Little Toller releases now (On Silbury Hill,  Whitney’s father, Ron Davis, is a Stanford geneticist whose research has contributed to the Human Genome Project. He has devoted himself to studying ME/CFS, which affects 20 million people worldwide yet receives little research funding; he calls it “the last major disease we know nothing about.” Testing his son’s blood, he found a problem with the citric acid cycle that produces ATP, essential fuel for the body’s cells – proof that there was a physiological reason for Whitney’s condition. Frustratingly, though, a Stanford colleague who examined Whitney prescribed a psychological intervention. This is in line with the current standard of care for ME/CFS: a graded exercise regime (nigh on impossible for someone who can’t get out of bed) and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Whitney’s father, Ron Davis, is a Stanford geneticist whose research has contributed to the Human Genome Project. He has devoted himself to studying ME/CFS, which affects 20 million people worldwide yet receives little research funding; he calls it “the last major disease we know nothing about.” Testing his son’s blood, he found a problem with the citric acid cycle that produces ATP, essential fuel for the body’s cells – proof that there was a physiological reason for Whitney’s condition. Frustratingly, though, a Stanford colleague who examined Whitney prescribed a psychological intervention. This is in line with the current standard of care for ME/CFS: a graded exercise regime (nigh on impossible for someone who can’t get out of bed) and cognitive behavioural therapy.