Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

#1962Club: A Dozen Books I’d Read Before

I totally failed to read a new-to-me 1962 publication this year. I’m disappointed in myself as I usually manage to contribute one or two reviews to each of Karen and Simon’s year clubs, and it’s always a good excuse to read some classics.

My mistake this time was to only get one option: Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, which I had my husband borrow for me from the university library. I opened it up and couldn’t make head or tail of it. I’m sure it’s very clever and meta, and I’ve enjoyed Nabokov before (Pnin, in particular), but I clearly needed to be in the right frame of mind for a challenge, and this month I was not.

Looking through the Goodreads list of the top 100 books from 1962, and spying on others’ contributions to the week, though, I can see that it was a great year for literature (aren’t they all?). Here are 12 books from 1962 that I happen to have read before, most of which I’ve reviewed here in the past few years. I’ve linked to those and/or given review excerpts where I have them, and the rest I describe to the best of my muzzy memory.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken – The snowy scene on the cover and described in the first two paragraphs drew me in and the story, a Victorian-set fantasy with notes of Oliver Twist and Jane Eyre, soon did, too. Dickensian villains are balanced out by some equally Dickensian urchins and helpful adults, all with hearts of gold. There’s something perversely cozy about the plight of an orphan in children’s books: the characters call to the lonely child in all of us; we rejoice to see how ingenuity and luck come together to defeat wickedness. There are charming passages here in which familiar smells and favourite foods offer comfort. This would make a perfect stepping stone from Roald Dahl to one of the Victorian classics.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

Instead of a Letter by Diana Athill – This was Athill’s first book, published when she was 45. An unfortunate consequence of my not having read the memoirs in the order in which they are written is that much of the content of this one seemed familiar to me. It hovers over her childhood (the subject of Yesterday Morning) and centres in on her broken engagement and abortion, two incidents revisited in Somewhere Towards the End. Although Athill’s careful prose and talent for candid self-reflection are evident here, I am not surprised that the book made no great waves in the publishing world at the time. It was just the story of a few things that happened in the life of a privileged Englishwoman. Only in her later life has Athill become known as a memoirist par excellence.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

The Drowned World by J.G. Ballard – (Read in October 2011.) Quite possibly the first ‘classic’ science fiction work I’d ever read. I found Ballard’s debut dated, with passages of laughably purple prose, poor character development (Beatrice is an utter Bond Girl cliché), and slow plot advancement. It sounded like a promising environmental dystopia – perhaps a forerunner of Oryx and Crake – but beyond the plausible vision of a heated-up and waterlogged planet, the book didn’t have much to offer. The most memorable passage was when Strangman drains the water and Kerans discovers Leicester Square beneath; he walks the streets and finds them uninhabited except by sea creatures clogging the cinema entrances. That was quite a potent, striking image. But the scene that follows, involving stereotyped ‘Negro’ guards, seemed like a poor man’s Lord of the Flies rip-off.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Carson’s first chapter imagines an American town where things die because nature stops working as it should. Her main target was insecticides that were known to kill birds and had presumed negative effects on human health through the food chain and environmental exposure. Although the details may feel dated, the literary style and the general cautions against submitting nature to a “chemical barrage” remain potent.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson – I loved the offbeat voice and unreliable narration, and the way that the Blackwood house is both a refuge and a prison for the sisters. “Where could we go?” Merricat asks Constance when she expresses concern that she should have given the girl a more normal life. “What place would be better for us than this? Who wants us, outside? The world is full of terrible people.” As the novel goes on, you ponder who is protecting whom, and from what. There are a lot of great scenes, all so discrete that I could see this working very well as a play with just a few backdrops to represent the house and garden. It has the kind of small cast and claustrophobic setting that would translate very well to the stage.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

Tales from Moominvalley by Tove Jansson – Moomintroll discovers a dragon small enough to be kept in a jar; laughter brings a fearful child back from literal invisibility. But what struck me more was the lessons learned by neurotic creatures. In “The Fillyjonk who believed in Disasters,” the title character fixates on her belongings, but when a gale and a tornado come and sweep it all away, she experiences relief and joy. My other favourite was “The Hemulen who loved Silence.” After years as a fairground ticket-taker, he can’t wait to retire and get away from the crowds and the noise, but once he’s obtained his precious solitude he realizes he needs others after all. In “The Fir Tree,” the Moomins, awoken midway through hibernation, get caught up in seasonal stress and experience Christmas for the first time.

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats – A perennial favourite from my childhood, with a paper-collage style that has influenced many illustrators. Just looking at the cover makes me nostalgic for the sort of wintry American mornings when I’d open an eye to a curiously bright aura from around the window, glance at the clock and realize my mom had turned off my alarm because it was a snow day and I’d have nothing ahead of me apart from sledding, playing boardgames and drinking hot cocoa with my best friend. There was no better feeling.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle – (Reread in 2021.) I probably picked this up at age seven or so, as a follow-on from the Chronicles of Narnia. Interplanetary stories have never held a lot of interest for me. As a child, I was always more drawn to talking-animal stuff. Again I found the travels and settings hazy. It’s admirable of L’Engle to introduce kids to basic quantum physics, and famous quotations via Mrs. Who, but this all comes across as consciously intellectual rather than organic and compelling. Even the home and school talk feels dated. I most appreciated the thought of a normal – or even not very bright – child like Meg saving the day through bravery and love. This wasn’t for me, but I hope that for some kids, still, it will be pure magic.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing – I read this feminist classic in my early twenties, in the days when I was working at a London university library. Lessing wrote autofiction avant la lettre, and the gist of this novel is that ‘Anna’, a writer, divides her life into four notebooks of different colours: one about her African upbringing, another about her foray into communism, a third containing an autobiographical novel in progress, and the fourth a straightforward journal. The fabled golden notebook is the unified self she tries to create as her romantic life and mental health become more complicated. Julianne Pachico read this recently and found it very powerful. I think I was too young for this and so didn’t appreciate it at the time. Were I to reread it, I imagine I would get a lot more out of it.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer – More autofiction. Like a nursery rhyme gone horribly wrong, this is the story of a woman who can’t keep it together. She’s the woman in the shoe, the wife whose pumpkin-eating husband keeps her safe in a pumpkin shell, the ladybird flying home to find her home and children in danger. Aged 31 and already on her fourth husband, the narrator, known only as Mrs. Armitage, has an indeterminate number of children. Her current husband, Jake, is a busy filmmaker whose philandering soon becomes clear, starting with the nanny. A breakdown at Harrods is the sign that Mrs. A. isn’t coping. Most chapters begin in medias res and are composed largely of dialogue, including with Jake or her therapist. The book has a dark, bitter humour and brilliantly recreates a troubled mind.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – This was required reading in high school, a novella and circadian narrative depicting life for a prisoner in a Soviet gulag. And that’s about all I can tell you about it. I remember it being just as eye-opening and depressing as you might expect, but pretty readable for a translated classic.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye – Tangye wasn’t a cat fan to start with, but Monty won him over. He lived with newlyweds Derek and Jeannie first in the London suburb of Mortlake, then on their flower farm in Cornwall. When they moved to Minack, there was a sense of giving Monty his freedom and taking joy in watching him live his best life. They were evacuated to St Albans and briefly lived with Jeannie’s parents and Scottie dog, who became Monty’s nemesis. Monty survived into his 16th year, happily tolerating a few resident birds. Tangye writes warmly and humorously about Monty’s ways and his own development into a man who is at a cat’s mercy. This was really the perfect chronicle of life with a cat, from adoption through farewell. Simon thought so, too.

Here’s hoping I make a better effort at the next year club!

Book Serendipity in the Final Months of 2020

I call it Book Serendipity when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something pretty bizarre in common. Because I have so many books on the go at once (20+), I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents than some. I also list these occasional reading coincidences on Twitter. (Earlier incidents from the year are here, here, and here.)

- Eel fishing plays a role in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson.

- A girl’s body is found in a canal in First Love, Last Rites by Ian McEwan and Carrying Fire and Water by Deirdre Shanahan.

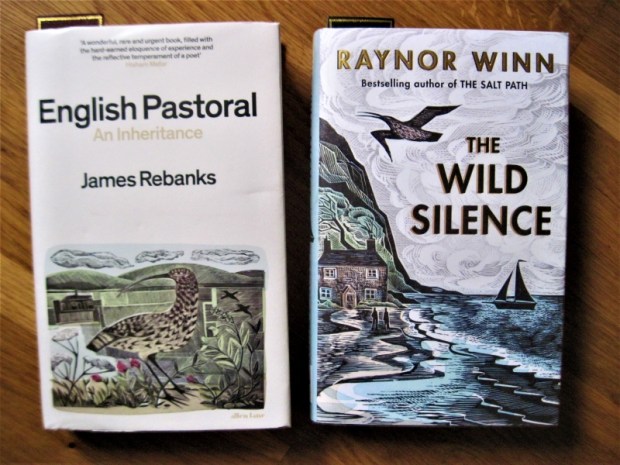

- Curlews on covers by Angela Harding on two of the most anticipated nature books of the year, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Wild Silence by Raynor Winn (and both came out on September 3rd).

- Thanksgiving dinner scenes feature in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid.

- A gay couple has the one man’s mother temporarily staying on the couch in 666 Charing Cross Road by Paul Magrs and Memorial by Bryan Washington.

- I was reading two “The Gospel of…” titles at once, The Gospel of Eve by Rachel Mann and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson (and I’d read a third earlier in the year, The Gospel of Trees by Apricot Irving).

- References to Dickens’s David Copperfield in The Cider House Rules by John Irving and Mudbound by Hillary Jordan.

- The main female character has three ex-husbands, and there’s mention of chin-tightening exercises, in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and The Pumpkin Eater by Penelope Mortimer.

- A Welsh hills setting in On the Red Hill by Mike Parker and Along Came a Llama by Ruth Janette Ruck.

- Rachel Carson and Silent Spring are mentioned in A Year on the Wing by Tim Dee, The Frayed Atlantic Edge by David Gange, English Pastoral by James Rebanks and The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson. SS was also an influence on Losing Eden by Lucy Jones, which I read earlier in the year.

- There’s nude posing for a painter or photographer in The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel, How to Be Both by Ali Smith, and Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth.

- A weird, watery landscape is the setting for The Swallowed Man by Edward Carey and Piranesi by Susanna Clarke.

- Bawdy flirting between a customer and a butcher in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Just Like You by Nick Hornby.

- Corbels (an architectural term) mentioned in The Idea of Perfection by Kate Grenville and Wakenhyrst by Michelle Paver.

- Near or actual drownings (something I encounter FAR more often in fiction than in real life, just like both parents dying in a car crash) in The Idea of Perfection, The Glass Hotel, The Gospel of Eve, Wakenhyrst, and Love and Other Thought Experiments.

- Nematodes are mentioned in The Gospel of the Eels by Patrik Svensson and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A toxic lake features in The New Wilderness by Diane Cook and Real Life by Brandon Taylor (both were also on the Booker Prize shortlist).

- A black scientist from Alabama is the main character in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- Graduate studies in science at the University of Wisconsin, and rivals sabotaging experiments, in Artifact by Arlene Heyman and Real Life by Brandon Taylor.

- A female scientist who experiments on rodents in Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi and Artifact by Arlene Heyman.

- There are poems about blackberrying in Dearly by Margaret Atwood, Passport to Here and There by Grace Nichols, and How to wear a skin by Louisa Adjoa Parker. (Nichols’s “Blackberrying Black Woman” actually opens with “Everyone has a blackberry poem. Why not this?” – !)

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Nonfiction Catch-Up: Long-Term Thinking, Finding a Home in Wales, Eels

Not long now until Nonfiction November. I’m highlighting three nonfiction books I’ve read over the last few months; any of them would be well worth your time if you’re still looking for some new books to add to the pile. I’ve got a practical introduction to the philosophy and politics of long-term/intergenerational planning, a group biography about the two gay couples who inhabited a house in the Welsh hills in turn, and a wide-ranging work on eels.

The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World by Roman Krznaric

I saw Krznaric introduce this via a digital Hay Festival session back in May. He is an excellent speaker and did an admirable job of conveying all the major ideas from his recent work within a half-hour presentation. Unfortunately, this meant that reading the book itself didn’t add much for me, although it goes deeper into his propositions and is illustrated with unique, helpful figures.

I saw Krznaric introduce this via a digital Hay Festival session back in May. He is an excellent speaker and did an admirable job of conveying all the major ideas from his recent work within a half-hour presentation. Unfortunately, this meant that reading the book itself didn’t add much for me, although it goes deeper into his propositions and is illustrated with unique, helpful figures.

Without repeating from my write-up of the Festival talk, then, I’ll add in points and quotes that struck me:

- “some of the fundamental ways we organise society, from nation states and representative democracy to consumer culture and capitalism itself, are no longer appropriate for the age we live in.”

- 100 years as the minimum timeframe to think about (i.e., a long human life) – “taking us beyond the ego boundary of our own mortality so we begin to imagine futures that we can influence yet not participate in ourselves.”

- “The phones in our pockets have become the new factory clocks, capturing time that was once our own and offering in exchange a continuous electronic now full of infotainment, advertising and fake news. The distraction industry works by cleverly tapping into our ancient mammalian brains: our ears prick up at the ping of an arriving message … Facebook is Pavlov, and we’re the dogs.”

- The Intergenerational Solidarity Index as a way of assessing governments’ future preparation: long-term democracies tend to perform better, though they aren’t perfect; Iceland scores the highest of all, followed by Sweden.

- Further discussion of Doughnut Economics (a model developed by Krznaric’s wife, Kate Raworth), which pictures the sweet spot humans need to live in between a social foundation and the ecological ceiling; failures lead to overshoot or shortfall.

- Four fundamental barriers to change: outdated institutional designs (our basic political systems), the power of vested interests (fossil fuel companies, Amazon, et al.), current insecurity (refugees), and “insufficient sense of crisis” – we’re like frogs in a gradually boiling pot, he says, and need to be jolted out of our complacency.

This is geared more towards economics and politics than much of what I usually read, yet fits in well with other radical visions of the future I’ve engaged with this year (some of them more environmentalist in approach), including Footprints by David Farrier, The Future Earth by Eric Holthaus, and Notes from an Apocalypse by Mark O’Connell.

With thanks to WH Allen for the free copy for review.

On the Red Hill: Where Four Lives Fell into Place by Mike Parker (2019)

I ordered a copy from Blackwell’s after this made it through to the Wainwright Prize shortlist – it went on to be named the runner-up in the UK nature writing category. It’s primarily a memoir/group biography about Parker, his partner Peredur, and George and Reg, the couple who previously inhabited their home of Rhiw Goch in the Welsh Hills and left it to the younger pair in their wills. In structuring the book into four parts, each associated with an element, a season, a direction of the compass and a main character, Parker focuses on the rhythms of the natural year. The subtitle emphasizes the role Rhiw Goch played, providing all four with a sense of belonging in a rural setting not traditionally welcoming to homosexuals.

I ordered a copy from Blackwell’s after this made it through to the Wainwright Prize shortlist – it went on to be named the runner-up in the UK nature writing category. It’s primarily a memoir/group biography about Parker, his partner Peredur, and George and Reg, the couple who previously inhabited their home of Rhiw Goch in the Welsh Hills and left it to the younger pair in their wills. In structuring the book into four parts, each associated with an element, a season, a direction of the compass and a main character, Parker focuses on the rhythms of the natural year. The subtitle emphasizes the role Rhiw Goch played, providing all four with a sense of belonging in a rural setting not traditionally welcoming to homosexuals.

Were George and Reg the ‘only gays in the village,’ as the Little Britain sketch has it? Impossible to say, but when they had Powys’ first same-sex civil partnership ceremony in February 2006, they’d been together nearly 60 years. By the time Parker and his partner took over the former guesthouse, gay partnerships were more accepted. In delving back into his friends’ past, then, he conjures up another time: George fought in the Second World War, and for the first 18 years he was with Reg their relationship was technically illegal. But they never rubbed it in any faces, preferring to live quietly, traveling on the Continent and hosting guests at their series of Welsh B&Bs; their politics was conservative, and they were admired locally for their cooking and hospitality (Reg) and endurance cycling (George).

There are lots of in-text black-and-white photographs of Reg and George over the years and of Rhiw Goch through the seasons. Using captioned photos, journal entries, letters and other documents, Parker gives a clear impression of his late friends’ characters. There is something pitiable about both: George resisting ageing with nude weightlifting well into his sixties; Reg still essentially ashamed of his sexuality as well as his dyslexia. I felt I got to know the younger protagonists less well, but that may simply be because their stories are ongoing. It’s remarkable how Welsh Parker now seems: though he grew up in the English Midlands, he now speaks decent Welsh and has even stood for election for the Plaid Cymru party.

It’s rare to come across something in the life writing field that feels genuinely sui generis. There were moments when my attention waned (e.g., George’s feuds with the neighbors), but so strong is the overall sense of time, place and personality that this is a book to prize.

The Gospel of the Eels: A Father, a Son and the World’s Most Enigmatic Fish by Patrik Svensson

[Translated from the Swedish by Agnes Broomé]

“When it comes to eels, an otherwise knowledgeable humanity has always been forced to rely on faith to some extent.”

We know the basic facts of the European eel’s life cycle: born in the Sargasso Sea, it starts off as a larva and then passes through three stages that are almost like separate identities: glass eel, yellow eel, silver eel. After decades underwater, it makes its way back to the Sargasso to spawn and die. Yet so much about the eel remains a mystery: why the Sargasso? What do the creatures do for all the time in between? Eel reproduction still has not been observed, despite scientists’ best efforts. Among the famous names who have researched eels are Aristotle, Sigmund Freud and Rachel Carson, all of whom Svensson discusses at some length. He even suggests that, for Freud, the eel was a suitable early metaphor for the unconscious – “an initial insight into how deeply some truths are hidden.”

We know the basic facts of the European eel’s life cycle: born in the Sargasso Sea, it starts off as a larva and then passes through three stages that are almost like separate identities: glass eel, yellow eel, silver eel. After decades underwater, it makes its way back to the Sargasso to spawn and die. Yet so much about the eel remains a mystery: why the Sargasso? What do the creatures do for all the time in between? Eel reproduction still has not been observed, despite scientists’ best efforts. Among the famous names who have researched eels are Aristotle, Sigmund Freud and Rachel Carson, all of whom Svensson discusses at some length. He even suggests that, for Freud, the eel was a suitable early metaphor for the unconscious – “an initial insight into how deeply some truths are hidden.”

But there is a more personal reason for Svensson’s fascination with eels. As a boy he joined his father in eel fishing on Swedish summer nights. It was their only shared hobby; the only thing they ever talked about. His father was as much a mystery to him as eels are to science. And it was only as his father was dying of a cancer caused by his long road-paving career that Svensson came to understand secrets he’d kept hidden for decades.

Chapters alternate between this family story and the story of the eels. The book explores eels’ place in culture (e.g., Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum) and their critically endangered status due to factors such as a herpes virus, nematode infection, pollution, overfishing and climate change. A prior curiosity about marine life would be helpful to keep you going through this, but the prose is lovely enough to draw in even those with a milder interest in nature writing.

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

One of my recent borrows from the public library’s children’s section was the picture book Think of an Eel by Karen Wallace. Her unrhymed, alliterative poetry and the paintings by Mike Bostock beautifully illustrate the eel’s life cycle and journey.

You simply must hear folk singer Kitty Macfarlane’s gorgeous song “Glass Eel” – literally about eels, it’s also concerned with migration, borders and mystery.

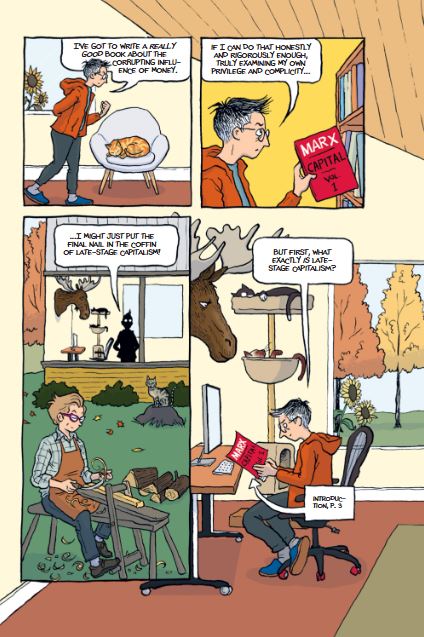

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

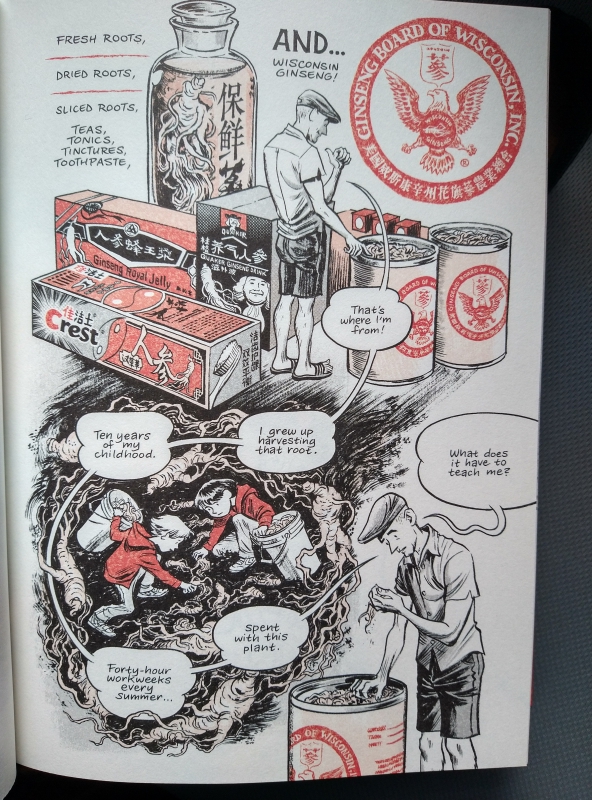

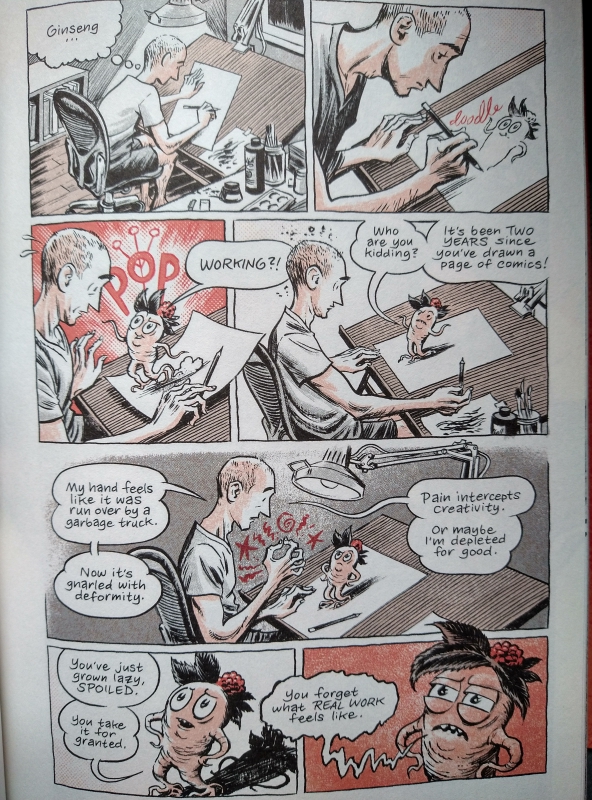

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world.

The Emma Press has published poetry pamphlets before, but this is their inaugural full-length work. Rachel Spence’s second collection is in two parts: first is “Call & Response,” a sonnet sequence structured as a play and considering her relationship with her mother. Act 1 starts in 1976 and zooms forward to key moments when they fell out and then reversed their estrangement. The next section finds them in the new roles of patient and carer. “Your final check-up. August. Nimbus clouds / prised open by Delft blue. Waiting is hard.” In Act 3, death is near; “in that quantum hinge, we made / an alphabet from love’s ungrammared stutter.” The poems of the last act are dated precisely, not just to a month and year as earlier but down to the very day, hour and minute. Whether in Ludlow or Venice, Spence crystallizes moments from the ongoingness of grief, drawing images from the natural world. Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my

Not only the pun-tastic title, but also the excellent nominative determinism of chef and food historian Dr Neil Buttery’s name, earned this a place in my  Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Foust’s fifth collection – at 41 pages, the length of a long chapbook – is in conversation with the language and storyline of 1984. George Orwell’s classic took on new prescience for her during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, a period marked by a pandemic as well as by corruption, doublespeak and violence. “Rally

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

Tomkins first wrote this for the Bath Prize in 2018 and was longlisted. She initially sent the book out to science fiction publishers but was told that it wasn’t ‘sci-fi enough’. I can see how it could fall into the gap between literary fiction and genre fiction: though it’s set on other planets and involves space travel, its speculative nature is understated; it feels more realist. A memorable interrogation of longing and belonging, this novella ponders the value of individuals and their choices in the midst of inexorable planetary trajectories.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings.

North of Ordinary by John Rolfe Gardiner (Bellevue Literary Press, January 14): I read 5 of 10 stories about young men facing life transitions and enjoyed the title one set at a thinly veiled Liberty University but found the rest dated in outlook; all have too-sudden endings. If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.

If Nothing by Matthew Nienow (Alice James Books, January 14): Straightforward poems about giving up addiction and seeking mental health help in order to be a good father.  The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

The Cannibal Owl by Aaron Gwyn (Belle Point Press, January 28): An orphaned boy is taken in by the Comanche in 1820s Texas in a brutal novella for fans of Cormac McCarthy.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.

Memorial Days by Geraldine Brooks (Viking, February 4): This elegant bereavement memoir chronicles the sudden death of Brooks’s husband (journalist Tony Horwitz) in 2019 and her grief retreat to Flinders Island, Australia.  Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

Reading the Waves by Lidia Yuknavitch (Riverhead, February 4): Yuknavitch’s bold memoir-in-essays focuses on pivotal scenes and repeated themes from her life as she reckons with trauma and commemorates key relationships. (A little too much repeated content from The Chronology of Water for me.)

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

A character who startles very easily (in the last two cases because of PTSD) in Life before Man by Margaret Atwood, A History of Sound by Ben Shattuck, and Disconnected by Eleanor Vincent.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

The author’s mother repeatedly asked her daughter a rhetorical question along the lines of “Do you know what I gave up to have you?” in Permission by Elissa Altman and Without Exception by Pam Houston.

#1 One of the books I read ‘in preparation’ for attending that conference was Small World by David Lodge, a comedic novel about professors on the international conference circuit. I’ve included it as one of the

#1 One of the books I read ‘in preparation’ for attending that conference was Small World by David Lodge, a comedic novel about professors on the international conference circuit. I’ve included it as one of the  #2 Flights and “small world” connections also fill the linked short story collection

#2 Flights and “small world” connections also fill the linked short story collection  #3 If you can bear to remember the turbulence of recent history,

#3 If you can bear to remember the turbulence of recent history,  #4 That punning title reminded me of

#4 That punning title reminded me of

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.)

Oldest author read this year: Peggy Seeger was 82 when her memoir First Time Ever was published. I haven’t double-checked the age of every single author, but I think second place at 77 is a tie between debut novelist Arlene Heyman for Artifact and Sue Miller for Monogamy. (I don’t know how old Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren, the joint authors of The Consolation of Nature, are; Mynott may actually be the oldest overall, and their combined age is likely over 200.) Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

Youngest author read this year: You might assume it was 16-year-old Dara McAnulty with Diary of a Young Naturalist, which won the Wainwright Prize (as well as the An Post Irish Book Award for Newcomer of the Year, the Books Are My Bag Reader Award for Non-Fiction, and the Hay Festival Book of the Year!) … or Thunberg, above, who was 16 when her book came out. They were indeed tied for youngest until, earlier in December, I started reading The House without Windows (1927) by Barbara Newhall Follett, a bizarre fantasy novel published when the child prodigy was 12.

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay

The book that made me laugh the most: Kay’s Anatomy by Adam Kay The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

The book that put a song in my head every single time I looked at it, much less read it: I Am an Island by Tamsin Calidas (i.e., “I Am a Rock” by Simon and Garfunkel, which, as my husband pointed out, has very appropriate lyrics for 2020: “In a deep and dark December / I am alone / Gazing from my window to the streets below … Hiding in my room / Safe within my womb / I touch no one and no one touches me.”)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.)

Most unexpectedly apt lines encountered in a book: “People came to church wearing masks, if they came at all. They’d sit as far from each other as they could.” (Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. Describing not COVID-19 times but the Spanish flu.) Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!)

Most ironic lines encountered in a book: “September 12—In the ongoing hearings, Senator Joseph Biden pledges to consider the Bork nomination ‘with total objectivity,’ adding, ‘You have that on my honor not only as a senator, but also as the Prince of Wales.’ … October 1—Senator Joseph Biden is forced to withdraw from the Democratic presidential race when it is learned that he is in fact an elderly Norwegian woman.” (from the 1987 roundup in Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits – Biden has been on the U.S. political scene, and mocked, for 3.5+ decades!) Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

Best first line encountered this year: “And then there was the day when Addie Moore made a call on Louis Waters.” (Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf)

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan

The downright strangest books I read this year: Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony, A Traveller at the Gates of Wisdom by John Boyne, The House Without Windows by Barbara Newhall Follett, and The Child in Time by Ian McEwan