Wellcome Book Prize Shadow Panel & Two Longlist Reviews

I’m delighted to announce the other book bloggers on my Wellcome Book Prize 2018 shadow panel: Paul Cheney of Halfman, Halfbook, Annabel Gaskell of Annabookbel, Clare Rowland of A Little Blog of Books, and Dr. Laura Tisdall. Once the shortlist is announced on Tuesday the 20th, we’ll be reading through the six nominees and sharing our thoughts. Before the official winner is announced at the end of April we will choose our own shadow winner.

I’ve been working my way through some of the longlisted titles I was able to access via the public library and NetGalley. Here’s my latest two (both  ):

):

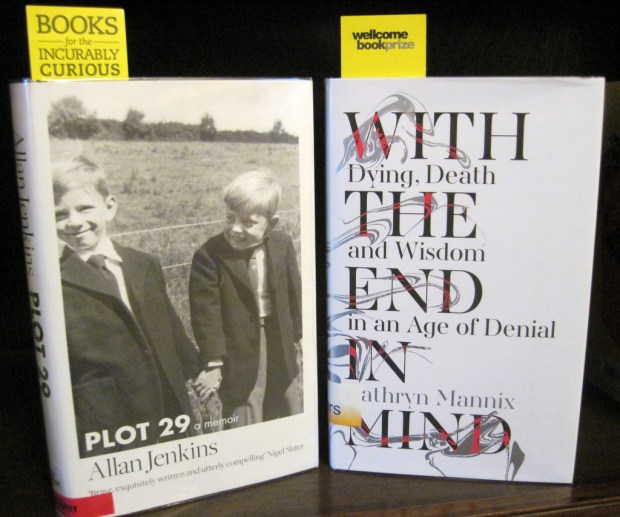

Plot 29: A Memoir by Allan Jenkins

This is an unusual hybrid memoir: it’s a meditative tour through the gardening year, on a plot in London and at his second home in his wife’s native Denmark. But it’s also the story of how Jenkins, editor of the Observer Food Monthly, investigated his early life. Handed over to a Barnardo’s home at a few months of age, he was passed between various family members and a stepfather (with some degree of neglect: his notes show scabies, rickets and TB) and then raised by strict foster parents in Devon with his beloved older half-brother, Christopher. It’s interesting to read that initially Jenkins intended to write a simple gardening diary, with a bit of personal stuff thrown in. But as he got further into the project, it started to morph.

This cover image is so sweet. It’s a photograph from Summer 1959 of Christopher and Allan (on the right, aged five), just after they were taken in by their foster parents in Devon.

The book has a complicated chronology: though arranged by month, within chapters its fragments jump around in time, a year or a date at the start helping the reader to orient herself between flashbacks and the contemporary story line. Sections are often just a paragraph long; sometimes up to a page or two. I suspect some will find the structure difficult and distancing. It certainly made me read the book slowly, which I think was the right way. You take your time adjusting to the gradual personal unveiling just as you do to the slow turn of the seasons. When major things do happen – meeting his mother in his 30s; learning who his father was in his 60s – they’re almost anticlimactic, perhaps because of the rather flat style. It’s the process that has mattered, and gardening has granted solace along the way.

I’m grateful to the longlist for making me aware of a book I otherwise might never have heard about. I don’t think the book’s mental health theme is strong enough for it to make the shortlist, but I enjoyed reading it and I’ll also take a look at Jenkins’s upcoming book, Morning, about the joys of being an early riser. (Ironic after my recent revelations about my own sleep patterns!)

Favorite lines:

“Solitude plus community, the constant I search for, the same as the allotment”

“The last element to be released from Pandora’s box, they say, was hope. So I will mourn the children we once were and I will sow chicory for bitterness. I will plant spring beans and alliums. I’ll look after them.”

“As a journalist, I have learned the five Ws – who, what, where, when, why. They are all needed to tell a story, we are taught, but too many are missing in my tale.”

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial by Kathryn Mannix

This is an excellent all-round guide to preparation for death. It’s based around relatable stories of the patients Mannix met in her decades working in the fields of cancer treatment and hospice care. She has a particular interest in combining CBT with palliative care to help the dying approach their remaining time with realism rather than pessimism. In many cases this involves talking patients and their loved ones through the steps of dying and explaining the patterns – decreased energy, increased time spent asleep, a change in breathing just before the end – as well as being clear about how suffering can be eased.

I read the first 20% on my Kindle and then skimmed the rest in a library copy. This was not because I wasn’t enjoying it, but because it was a two-week loan and I was conscious of needing to move on to other longlist books. It may also be because I have read quite a number of books with similar themes and scope – including Caitlin Doughty’s two books on death, Caring for the Dying by Henry Fersko-Weiss, Being Mortal by Atul Gawande, and Waiting for the Last Bus by Richard Holloway. Really this is the kind of book I would like to own a copy of and read steadily, just a chapter a week. Mannix’s introductions to each section and chapter, and the Pause for Thought pages at the end of each chapter, mean the book lends itself to being read as a handbook, perhaps in tandem with an ill relative.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

The book is unique in giving a doctor’s perspective but telling the stories of patients and their families, so we see a whole range of emotions and attitudes: denial, anger, regret, fear and so on. Tears were never far from my eyes as I read about a head teacher with motor neurone disease; a pair of women with metastatic breast cancer who broke their hips and ended up as hospice roommates; a beautiful young woman who didn’t want to stop wearing her skinny jeans even though they were exacerbating her nerve pain, as then she’d feel like she’d given up; and a husband and wife who each thought the other didn’t know she was dying of cancer.

Mannix believes there’s something special about people who are approaching the end of their life. There’s wisdom, dignity, even holiness surrounding them. It’s clear she feels she’s been honored to work with the dying, and she’s helped to propagate a healthy approach to death. As her children told her when they visited her dying godmother, “you and Dad [a pathologist] have spent a lifetime preparing us for this. No one else at school ever talked about death. It was just a Thing in our house. And now look – it’s OK. We know what to expect. We don’t feel frightened. We can do it. This is what you wanted for us, not to be afraid.”

I would be happy to see this advance to the shortlist.

Favorite lines:

“‘So, how long has she got?’ I hate this question. It’s almost impossible to answer, yet people ask as though it’s a calculation of change from a pound. It’s not a number – it’s a direction of travel, a movement over time, a tiptoe journey towards a tipping point. I give my most honest, most direct answer: I don’t know exactly. But I can tell you how I estimate, and then we can guesstimate together.”

“we are privileged to accompany people through moments of enormous meaning and power; moments to be remembered and retold as family legends and, if we get the care right, to reassure and encourage future generations as they face these great events themselves.”

Longlist strategy:

Currently reading: The Butchering Art by Lindsey Fitzharris: a history of early surgery and the fight against hospital infection, with a focus on the life and work of Joseph Lister.

Up next: I’ve requested review copies of The White Book by Han Kang and Mayhem by Sigrid Rausing, but if they don’t make it to the shortlist they’ll slip down the list of priorities.

In Shock by Rana Awdish: The doctor became the patient when Awdish, seven months pregnant, was rushed into emergency surgery with excruciating pain due to severe hemorrhaging into the space around her liver, later explained by a ruptured tumor. Having experienced brusque, cursory treatment, even from colleagues at her Detroit-area hospital, she was convinced that doctors needed to do better. This memoir is a gripping story of her own medical journey and a fervent plea for compassion from medical professionals.

In Shock by Rana Awdish: The doctor became the patient when Awdish, seven months pregnant, was rushed into emergency surgery with excruciating pain due to severe hemorrhaging into the space around her liver, later explained by a ruptured tumor. Having experienced brusque, cursory treatment, even from colleagues at her Detroit-area hospital, she was convinced that doctors needed to do better. This memoir is a gripping story of her own medical journey and a fervent plea for compassion from medical professionals.

Doctor by Andrew Bomback: Part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, this is a wide-ranging look at what it’s like to be a doctor. Bomback is a kidney specialist; his wife is also a doctor, and his father, fast approaching retirement, is the kind of old-fashioned, reassuring pediatrician who knows everything. Even the author’s young daughter likes playing with a stethoscope and deciding what’s wrong with her dolls. In a sense, then, Bomback uses fragments of family memoir to compare the past, present and likely future of medicine.

Doctor by Andrew Bomback: Part of the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series, this is a wide-ranging look at what it’s like to be a doctor. Bomback is a kidney specialist; his wife is also a doctor, and his father, fast approaching retirement, is the kind of old-fashioned, reassuring pediatrician who knows everything. Even the author’s young daughter likes playing with a stethoscope and deciding what’s wrong with her dolls. In a sense, then, Bomback uses fragments of family memoir to compare the past, present and likely future of medicine.

A Moment of Grace by Patrick Dillon [skimmed]: A touching short memoir of the last year of his wife Nicola Thorold’s life, in which she battled acute myeloid leukemia. Dillon doesn’t shy away from the pain and difficulties, but is also able to summon up some gratitude.

A Moment of Grace by Patrick Dillon [skimmed]: A touching short memoir of the last year of his wife Nicola Thorold’s life, in which she battled acute myeloid leukemia. Dillon doesn’t shy away from the pain and difficulties, but is also able to summon up some gratitude.  Get Well Soon: Adventures in Alternative Healthcare by Nick Duerden: British journalist Nick Duerden had severe post-viral fatigue after a run-in with possible avian flu in 2009 and was falsely diagnosed with ME / CFS. He spent a year wholeheartedly investigating alternative therapies, including yoga, massage, mindfulness and meditation, visualization, talk therapy and more. He never comes across as bitter or sorry for himself. Instead, he considered fatigue a fact of his new life and asked what he could do about it. So this ends up being quite a pleasant amble through the options, some of them more bizarre than others.

Get Well Soon: Adventures in Alternative Healthcare by Nick Duerden: British journalist Nick Duerden had severe post-viral fatigue after a run-in with possible avian flu in 2009 and was falsely diagnosed with ME / CFS. He spent a year wholeheartedly investigating alternative therapies, including yoga, massage, mindfulness and meditation, visualization, talk therapy and more. He never comes across as bitter or sorry for himself. Instead, he considered fatigue a fact of his new life and asked what he could do about it. So this ends up being quite a pleasant amble through the options, some of them more bizarre than others.  *Sight by Jessie Greengrass [skimmed]: I wanted to enjoy this, but ended up frustrated. As a set of themes (losing a parent, choosing motherhood, the ways in which medical science has learned to look into human bodies and minds), it’s appealing; as a novel, it’s off-putting. Had this been presented as a set of autobiographical essays, perhaps I would have loved it. But instead it’s in the coy autofiction mold where you know the author has pulled some observations straight from life, gussied up others, and then, in this case, thrown in a bunch of irrelevant medical material dredged up during research at the Wellcome Library.

*Sight by Jessie Greengrass [skimmed]: I wanted to enjoy this, but ended up frustrated. As a set of themes (losing a parent, choosing motherhood, the ways in which medical science has learned to look into human bodies and minds), it’s appealing; as a novel, it’s off-putting. Had this been presented as a set of autobiographical essays, perhaps I would have loved it. But instead it’s in the coy autofiction mold where you know the author has pulled some observations straight from life, gussied up others, and then, in this case, thrown in a bunch of irrelevant medical material dredged up during research at the Wellcome Library.

*Brainstorm: Detective Stories From the World of Neurology by Suzanne O’Sullivan: Epilepsy affects 600,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide, so it’s an important condition to know about. It is fascinating to see the range of behaviors seizures can be associated with. The guesswork is in determining precisely what is going wrong in the brain, and where, as well as how medicines or surgery could address the fault. “There are still far more unknowns than knowns where the brain is concerned,” O’Sullivan writes; “The brain has a mind of its own,” she wryly adds later on. (O’Sullivan won the Prize in 2016 for It’s All in Your Head.)

*Brainstorm: Detective Stories From the World of Neurology by Suzanne O’Sullivan: Epilepsy affects 600,000 people in the UK and 50 million worldwide, so it’s an important condition to know about. It is fascinating to see the range of behaviors seizures can be associated with. The guesswork is in determining precisely what is going wrong in the brain, and where, as well as how medicines or surgery could address the fault. “There are still far more unknowns than knowns where the brain is concerned,” O’Sullivan writes; “The brain has a mind of its own,” she wryly adds later on. (O’Sullivan won the Prize in 2016 for It’s All in Your Head.)  I’m also currently reading and enjoying two witty medical books, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris, and Chicken Unga Fever by Phil Whitaker, his collected New Statesman columns on being a GP.

I’m also currently reading and enjoying two witty medical books, The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth and Other Curiosities from the History of Medicine by Thomas Morris, and Chicken Unga Fever by Phil Whitaker, his collected New Statesman columns on being a GP. The Beautiful Cure: Harnessing Your Body’s Natural Defences by Daniel M. Davis

The Beautiful Cure: Harnessing Your Body’s Natural Defences by Daniel M. Davis

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne

The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne A History of God by Karen Armstrong

A History of God by Karen Armstrong Secrets in the Dark by Frederick Buechner

Secrets in the Dark by Frederick Buechner The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee

The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler

After I got back to the States from my year abroad, I spent a few years doing some intensive reading about progressive Christianity (it was sometimes also called the emergent church) and other religions, trying to decide if it was worth sticking with the faith I’d grown up in. Although I still haven’t definitively answered this for myself, and have drifted in and out of lots of churches over the last 12 years, two authors were key to me never ditching Christianity entirely: Brian McLaren and Marcus Borg.

After I got back to the States from my year abroad, I spent a few years doing some intensive reading about progressive Christianity (it was sometimes also called the emergent church) and other religions, trying to decide if it was worth sticking with the faith I’d grown up in. Although I still haven’t definitively answered this for myself, and have drifted in and out of lots of churches over the last 12 years, two authors were key to me never ditching Christianity entirely: Brian McLaren and Marcus Borg. McLaren founded the church we attend whenever we’re back in Maryland and is the author of over a dozen theology titles, including the New Kind of Christian trilogy of allegorical novels. For me his best book is A New Kind of Christianity, which pulls together all his recurrent themes. Borg, who died in 2015, wrote several books that made a big impression on me, but none more so than The Heart of Christianity, which is the best single book I’ve found about what Christianity can and should be, going back to Jesus’ way of peace and social justice and siphoning off the unhelpful doctrines that have accumulated over the centuries.

McLaren founded the church we attend whenever we’re back in Maryland and is the author of over a dozen theology titles, including the New Kind of Christian trilogy of allegorical novels. For me his best book is A New Kind of Christianity, which pulls together all his recurrent themes. Borg, who died in 2015, wrote several books that made a big impression on me, but none more so than The Heart of Christianity, which is the best single book I’ve found about what Christianity can and should be, going back to Jesus’ way of peace and social justice and siphoning off the unhelpful doctrines that have accumulated over the centuries. Any number of other Christian books and authors have been helpful to me over the years (Secrets in the Dark by Frederick Buechner, How (Not) to Speak of God by Peter Rollins, Falling Upward by Richard Rohr, An Altar in the World by Barbara Brown Taylor, Without Buddha I Could Not be a Christian by Paul Knitter, Unapologetic by Francis Spufford, and various by Kathleen Norris, Rowan Williams, Richard Holloway and Anne Lamott), reassuring me that it’s not all hellfire/pie in the sky mumbo-jumbo for anti-gay Republicans, but Borg and McLaren were there at the start of my journey.

Any number of other Christian books and authors have been helpful to me over the years (Secrets in the Dark by Frederick Buechner, How (Not) to Speak of God by Peter Rollins, Falling Upward by Richard Rohr, An Altar in the World by Barbara Brown Taylor, Without Buddha I Could Not be a Christian by Paul Knitter, Unapologetic by Francis Spufford, and various by Kathleen Norris, Rowan Williams, Richard Holloway and Anne Lamott), reassuring me that it’s not all hellfire/pie in the sky mumbo-jumbo for anti-gay Republicans, but Borg and McLaren were there at the start of my journey. Reading is my primary means of examining society as well as my own life, so it’s no wonder that I have turned to books to learn from some gender pioneers. Hanne Blank’s accessible social history Straight (2012) is particularly valuable for its revelation of the surprisingly short history of heterosexuality as a concept – the term has only existed since the 1860s. But the book that most helped me adjust my definitions of gender and broaden my tolerance was Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974).

Reading is my primary means of examining society as well as my own life, so it’s no wonder that I have turned to books to learn from some gender pioneers. Hanne Blank’s accessible social history Straight (2012) is particularly valuable for its revelation of the surprisingly short history of heterosexuality as a concept – the term has only existed since the 1860s. But the book that most helped me adjust my definitions of gender and broaden my tolerance was Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974). James Morris, born in 1926, was a successful reporter, travel writer, husband and father. Yet all along he knew he was meant to be female; it was something he had sensed for the first time as a young child sitting under the family piano: “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl … the conviction was unfaltering from the start.” In 1954 he began taking hormones to start his transition to womanhood, completed by a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972. This exceptional memoir of sex change evokes the swirl of determination and doubt, as well as the almost magical process of metamorphosing from one thing to another. Morris has been instrumental in helping me see sexuality as a continuum rather than a fixed entity.

James Morris, born in 1926, was a successful reporter, travel writer, husband and father. Yet all along he knew he was meant to be female; it was something he had sensed for the first time as a young child sitting under the family piano: “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl … the conviction was unfaltering from the start.” In 1954 he began taking hormones to start his transition to womanhood, completed by a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972. This exceptional memoir of sex change evokes the swirl of determination and doubt, as well as the almost magical process of metamorphosing from one thing to another. Morris has been instrumental in helping me see sexuality as a continuum rather than a fixed entity. The fact that I still haven’t completely given up meat is proof of how difficult it is to change, even once you’ve been convicted. We’ve gone from eating meat occasionally to almost never, and then mostly when we’re guests at other people’s houses. But if I really reminded myself to think about where my food was coming from, I’m sure we’d be even more hardline. Foer didn’t answer all my questions – what about offal and wild game, and why not go all the way to veganism? – but I appreciated that he never characterizes the decision to be vegetarian as an easy one. He recognizes the ways food is bound up with cultural traditions and family memories, but still thinks being true to one’s principles outweighs all. (He’s brave enough to suggest to middle America that it’s time to consider a turkey-free Thanksgiving!)

The fact that I still haven’t completely given up meat is proof of how difficult it is to change, even once you’ve been convicted. We’ve gone from eating meat occasionally to almost never, and then mostly when we’re guests at other people’s houses. But if I really reminded myself to think about where my food was coming from, I’m sure we’d be even more hardline. Foer didn’t answer all my questions – what about offal and wild game, and why not go all the way to veganism? – but I appreciated that he never characterizes the decision to be vegetarian as an easy one. He recognizes the ways food is bound up with cultural traditions and family memories, but still thinks being true to one’s principles outweighs all. (He’s brave enough to suggest to middle America that it’s time to consider a turkey-free Thanksgiving!) There’s nothing more routine than brushing your teeth, and I never thought I would learn a new way to do it at age 32! But that’s just what Ignore Your Teeth and They’ll Go Away by Sheldon Dov Sydney gave me. He advises these steps: (1) brushing with a dry brush to remove bits of food and plaque, (2) flossing, and (3) brushing with toothpaste as a polish and to freshen breath. It takes a little bit longer than your usual quick brush and thus I can’t often be bothered to do it, but it does always leave my mouth feeling super-clean.

There’s nothing more routine than brushing your teeth, and I never thought I would learn a new way to do it at age 32! But that’s just what Ignore Your Teeth and They’ll Go Away by Sheldon Dov Sydney gave me. He advises these steps: (1) brushing with a dry brush to remove bits of food and plaque, (2) flossing, and (3) brushing with toothpaste as a polish and to freshen breath. It takes a little bit longer than your usual quick brush and thus I can’t often be bothered to do it, but it does always leave my mouth feeling super-clean. I frequently succumb to negative self-talk, thinking “I can’t cope” or “There’s no way I could…” Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway by Susan Jeffers helped me see that I need to be more positive in my thought life. Originally published in 1987, the self-help classic says that at the base of every fear is a belief that “I can’t handle it.” Our fears are either of things that can happen to us (aging and natural disasters) or actions we might take (going back to school or changing jobs). You can choose to hold fear with either pain (leading to paralysis) or power (leading to action). This is still a struggle for me, but whenever I start to think “I can’t” I try to replace it with Jeffers’ mantra, “Whatever it is, I’ll handle it.”

I frequently succumb to negative self-talk, thinking “I can’t cope” or “There’s no way I could…” Feel the Fear and Do It Anyway by Susan Jeffers helped me see that I need to be more positive in my thought life. Originally published in 1987, the self-help classic says that at the base of every fear is a belief that “I can’t handle it.” Our fears are either of things that can happen to us (aging and natural disasters) or actions we might take (going back to school or changing jobs). You can choose to hold fear with either pain (leading to paralysis) or power (leading to action). This is still a struggle for me, but whenever I start to think “I can’t” I try to replace it with Jeffers’ mantra, “Whatever it is, I’ll handle it.”