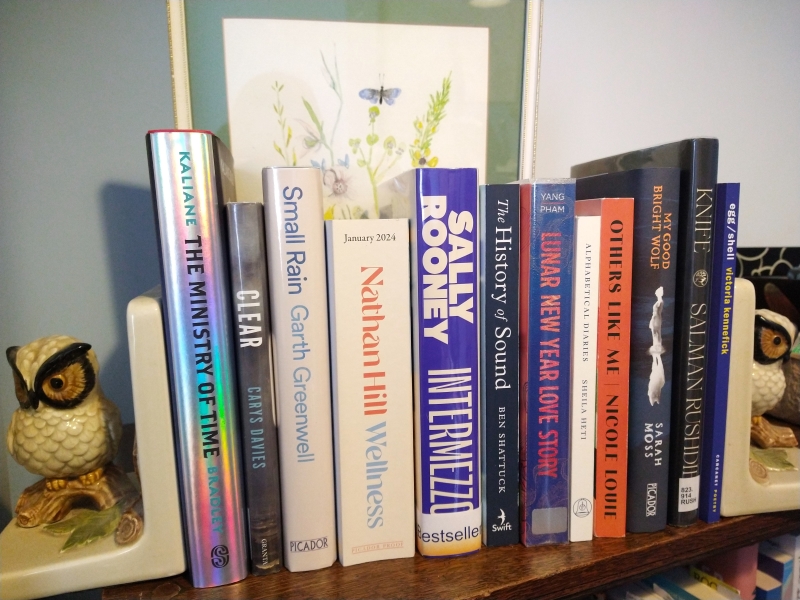

Book Serendipity, June to Mid-August 2024

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every couple of months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. People frequently ask how I remember all of these coincidences. The answer is: I jot them on scraps of paper or input them immediately into a file on my PC desktop; otherwise, they would flit away!

The following are in roughly chronological order.

- A self-induced abortion scene in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

- A woman who cleans buildings after hours, and a character named Tova who lives in the Seattle area in A Reason to See You Again by Jami Attenberg and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- Flirting with a surf shop employee in Sandwich by Catherine Newman and Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt.

- Living in Paris and keeping ticket stubs from all films seen in Paris Trance by Geoff Dyer and The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick.

- A schefflera (umbrella tree) is mentioned in Cheri by Jo Ann Beard and Company by Shannon Sanders.

- The Plague by Albert Camus is mentioned in Knife by Salman Rushdie and Stowaway by Joe Shute.

- Making egg salad sandwiches is mentioned in Cheri by Jo Ann Beard and Sandwich by Catherine Newman.

- Pet rats in Stowaway by Joe Shute and Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman. Rats are also mentioned in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo, and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- Eels feature in Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma, Late Light by Michael Malay, and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- Atlantic City, New Jersey is a location in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Company by Shannon Sanders.

The father is a baker in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma.

The father is a baker in Florence Adler Swims Forever by Rachel Beanland and Our Narrow Hiding Places by Kristopher Jansma.

- A New Zealand setting (but very different time periods) in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and The Colour by Rose Tremain.

- A mention of Melanie Griffith’s role in Working Girl in I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol and Happy Death Club by Naomi Westerman.

Ermentrude/Ermyntrude as an imagined alternate name in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and a pet’s name in Stowaway by Joe Shute.

Ermentrude/Ermyntrude as an imagined alternate name in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and a pet’s name in Stowaway by Joe Shute.

- A poet with a collection that was published on 6 August mentions a constant ringing in the ears: Joshua Jennifer Espinoza (I Don’t Want to Be Understood) and Keith Taylor (What Can the Matter Be?).

- A discussion of the original meaning of “slut” (a slovenly housekeeper) vs. its current sexualized meaning in Girlhood by Melissa Febos and Sandi Toksvig’s introduction to the story anthology Furies.

- An odalisque (a concubine in a harem, often depicted in art) is mentioned in I’m Mostly Here to Enjoy Myself by Glynnis MacNicol and The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley.

- Reading my second historical novel of the year in which there’s a disintegrating beached whale in the background of the story: first was Whale Fall by Elizabeth O’Connor, then Come to the Window by Howard Norman.

A short story in which a woman gets a job in online trolling in Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long and in the Virago Furies anthology (Helen Oyeyemi’s story).

A short story in which a woman gets a job in online trolling in Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t by Josie Long and in the Virago Furies anthology (Helen Oyeyemi’s story).

- Her partner, a lawyer, is working long hours and often missing dinner, leading the protagonist to assume that he’s having an affair with a female colleague, in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- A fierce boss named Jo(h)anna in Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- An OTT rendering of a Scottish accent in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A Padstow setting and a mention of Puffin Island (Cornwall) in The Cove by Beth Lynch and England as You Like It by Susan Allen Toth.

- A mention of the Big and Little Dipper (U.S. names for constellations) in Directions to Myself by Heidi Julavits and How We Named the Stars by Andrés N. Ordorica.

- A mention of Binghamton, New York and its university in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and We Would Never by Tova Mirvis.

- A character accidentally drinks a soapy liquid in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and one story of The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer.

The mother (of the bride or groom) takes over the wedding planning in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

The mother (of the bride or groom) takes over the wedding planning in We Would Never by Tova Mirvis and Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell.

- The ex-husband’s name is Jonah in The Mourner’s Bestiary by Eiren Caffall and We Would Never by Tova Mirvis.

- The husband’s name is John in Dot in the Universe by Lucy Ellmann and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- An affair is discovered through restaurant receipts in Summer Fridays by Suzanne Rindell and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A mention of eating fermented shark in The Museum of Whales You Will Never See by A. Kendra Greene and Test Kitchen by Neil D.A. Stewart.

- A mention of using one’s own urine as a remedy in Thunderstone by Nancy Campbell and Terminal Maladies by Okwudili Nebeolisa.

- The main character tries to get pregnant by a man even though one of the partners is gay in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and Until the Real Thing Comes Along by Elizabeth Berg.

- Motherhood is for women what war is for men: this analogy is presented in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case, Parade by Rachel Cusk, and Want, the Lake by Jenny Factor.

Childcare is presented as a lifesaver for new mothers in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

Childcare is presented as a lifesaver for new mothers in We Are Animals by Jennifer Case and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- A woman bakes bread for the first time in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans.

- A gay couple adopts a Latino boy in Greta & Valdin by Rebecca K Reilly and one story of There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

A husband who works on film projects in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

A husband who works on film projects in A Year of Biblical Womanhood by Rachel Held Evans and Liars by Sarah Manguso.

- A man is haunted by things his father said to him years ago in Parade by Rachel Cusk and one story in There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

- Two short story collections in a row in which a character is a puppet (thank you, magic realism!): The Man in the Banana Trees by Marguerite Sheffer, followed by There Is a Rio Grande in Heaven by Ruben Reyes, Jr.

- A farm is described as having woodworm in Mammoth by Eva Baltasar and Parade by Rachel Cusk.

- Sebastian as a proposed or actual name for a baby in Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus and Birdeye by Judith Heneghan.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

Wendell Berry’s “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer” & Why I Acquired My First Smartphone at Age 40.5

Wendell Berry is an American treasure: the 89-year-old Kentucky farmer is also a philosopher, poet, theologian, and writer of fiction, and many of his pronouncements bear the timeless wisdom of a biblical prophet. I’ve read his work from several genres and was curious to see how this 1987 essay – originally published in Harper’s Magazine and reprinted, along with some letters to the editor in response, plus extra commentary in the form of a 1990 essay, by Penguin in 2018 as the 50th and final entry in their Penguin Modern pamphlet series – might resonate with my own reluctance to adopt current technology.

The title essay is brief, barely filling 4.5 pages of a small-format paperback. It’s so concise that it would be difficult to summarize in many fewer words, but I’ll run through the points he makes across the initial essay, the replies to the correspondence, and a follow-up piece entitled “Feminism, the Body and the Machine” (1989). Berry laments his reliance on energy corporations and wants to limit that as much as possible. He decries consumerism in general; he isn’t going to acquire something just to be ‘keeping up with the times’. He doesn’t believe a computer will make his work better, and it doesn’t meet his criteria for a useful tool (smaller, cheaper and less energy-intensive than what it replaces; sourced locally and easily repaired by a non-specialist). He is perfectly happy with his current arrangement: he writes his work by hand and his wife types it up for him. He is loath to lose this human touch.

The letters to the editor, predictably, accuse him of self-righteousness for depicting his choice as the more virtuous one. The correspondents also felt they had to stand up for Berry’s wife, who might have better things to do than act as her husband’s secretary. This is the only time the author becomes slightly defensive, basically saying, ‘you don’t know anything about me, my wife or my marriage … maybe she wants to!’ He doubles down on the environmental harm caused by technology and consumerism, acknowledging his continued dependence on fossil fuels and vowing to avoid them, and unnecessary purchases, where possible.

If some technology does damage to the world, … then why is it not reasonable, and indeed moral, to try to limit one’s use of that technology?

To the extent that we consume, in our present circumstances, we are guilty. To the extent that we guilty consumers are conservationists, we are absurd. … can we do something directly to solve our share of the problem? … Why then is not my first duty to reduce, so far as I can, my own consumption?

If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer one is not to use one.

He even appears to speak prophetically to the rise of artificial intelligence:

My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can. … And in our time this means that we must save ourselves from the products that we are asked to buy in order, ultimately, to replace ourselves. The danger most immediately to be feared in ‘technological progress’ is the degradation and obsolescence of the body.

Certain of his arguments felt relevant to me as I ponder my own relationship to technology. I compose all my reviews on a 19-year-old personal computer that’s not connected to the Internet. I don’t listen to the radio and have seen maybe three films in the past two years. We’ve been television-free for a decade and I have never regretted it (Berry: “It is easy – it is even a luxury – to deny oneself the use of a television set, and I zealously practice that form of self-denial. Every time I see television (at other people’s houses), I am more inclined to congratulate myself on my deprivation.”).

I find it so hard to adjust to new tech that my reluctance may have shaded into suspicion. I’m certainly no early adopter, but I’d also object to the label “Luddite”: since 2013 I’ve been using e-readers, which are invaluable in my reviewing work. But for 15 years or more I have been looking at other people and their smartphones with disdain. I prided myself on my resistance. Stubbornness seemed like a virtue when the alternative was spending a lot of money on something I didn’t need.

Receiving my first cell phone in July 2004 (with my dad at left; at Dulles airport).

Two months ago, though, I finally gave in and accepted a hand-me-down Motorola Android phone from my father-in-law, after nearly 20 years of using an old-style mobile phone. As we were renegotiating our phone and Internet contract, I got virtually unlimited minutes and data on this device for £6/month, with no initial outlay. Had I been forced to make a purchase, I think I would still be holding out. But I had gotten to the point where refusal was cutting off my nose to spite my face. Why keep martyring myself – saying I couldn’t make important household phone calls because they drained my pay-as-you-go credit; learning complex workarounds to post to Instagram from my PC; taking crap photos on a digital camera held together with a rubber band? Why resist utility just for the sake of it?

To be clear, this was not a matter of saving time. I’m not a busy person. Plus I believe there is value in slowing down and acting deliberately. (See this book-based article I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2018 on the benefits of “wasting time.”) Mindless scrolling is as much a temptation on a PC as on a phone, so avoiding social media was not a motive for me; others with addictive tendencies may decide otherwise. Nor did I view convenience as reason enough per se. However, I admit I was attracted to the efficiency of a pocket-sized device that can at once replace a computer, pager, telephone, Rolodex, phonebook, camera, photo album, television screen, music player, camcorder, Dictaphone, stopwatch, calculator, map, satnav, flashlight, encyclopaedia, Kindle library, calendar, diary, Post-It notes, notebook, alarm clock and mirror. (Have I missed anything?) Talk about multi-tasking!

Out with the old, in with the new?

I would still say that I object to tech serving as a status symbol or a basis for self-importance, and I’d be pretty dubious about it ever being a worthwhile hobby. Should this phone fail me in future, I’ll copy my husband’s habit of buying a secondhand handset for £60–80. I wouldn’t acquire something that represented new extraction of rare resources. Treating things (or people) as disposable is anathema to me, something about which I know Berry would agree. I’m naturally parsimonious, obsessive about keeping things going for as long as possible and recycling them responsibly when they reach their end of life.

It’s one reason why I’ve gotten involved in the Repair Café movement. I volunteer for our local branch, which started up in February, on the admin and publicity side of things. The old-fashioned, make-do-and-mend ethos appeals to me. It’s the same spirit evoked in the lyrics of American singer-songwriter Mark Erelli’s “Analog Hero”:

He’s the fix-it man, the fix-it man

If he can’t put it back together, then it was never worth a damn

Maybe he’s crazy for trying to save what’s already gone

Now it ain’t even broken and we’re going for the upgrade

Nobody thinks twice ’bout what we’re really throwing away

It’s out with the old, in with the new…

I can imagine Wendell Berry still pecking out his words on a typewriter on his Kentucky farm. He’s an analogue hero, too. And he doesn’t go nearly as far as Mark Boyle, whose radical life experiment is recounted in The Way Home: Tales from a life without technology, which I reviewed for Shiny New Books in 2019.

I have pretty much made my peace with owning a smartphone. I have few apps and am still more likely to work at my PC or on paper. I’ll concede that I enjoy being able to post to X or Instagram wherever I am, and to keep up with messages on the go. (I used to have to say cryptic things to friends like, “once I leave the house, I will be unavailable except by text.”) Mostly, I’m relieved to have shed the frustrations of outmoded tech. Though I still keep my Nokia brick by my bedside as a trusty alarm clock – and a torch for when the cat wakes me between 2 and 5 each morning.

Ultimately, I feel, a smartphone is a tool like any other. It’s how you use it. Salman Rushdie comes to much the same conclusion about the would-be murder weapon wielded against him: “a knife is a tool, and acquires meaning from the use we make of it. It is morally neutral” (from Knife).

Berry’s argument about overreliance on energy remains a good one, but we are all so complicit in so many ways – even more so than in the late 1980s when he was writing – that avoiding the computer, and now the smartphone, doesn’t seem to hold particular merit. While this pamphlet will be but a quaint curio piece for most readers (rather than a parallel to the battle of wills I’ve conducted with myself), it is engaging and convincing, and the societal issues it considers are still ones to be wrestled with.

My copy was purchased with part of a £30 voucher I received free from Penguin UK for being part of their “Bookmarks” online community – answering polls, surveys, etc.

March’s Doorstopper: Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese (2009)

I’m squeaking in here on the 31st with the doorstopper I’ve been reading all month. I started Cutting for Stone in an odd situation on the 1st: We’d attempted to go to France that morning but were foiled by a fatal engine failure en route to the ferry terminal, so were riding in the cab of a recovery vehicle that was taking us and our car home. My poor husband sat beside the driver, trying to make laddish small talk about cars, while I wedged myself by the window and got lost in the early pages of Indian-American doctor Abraham Verghese’s saga of twins Marion and Shiva, born of an unlikely union between an Indian nun, Sister Mary Joseph Praise, and an English surgeon, Thomas Stone, at Missing Hospital in Addis Ababa in 1954.

What with the flashbacks and the traumatic labor, it takes narrator Marion over 100 pages to get born. That might seem like a Tristram Shandy degree of circumlocution, but there was nary a moment when my interest flagged during this book’s 50-year journey with a medical family starting in a country I knew nothing about. I was reminded of Midnight’s Children, in that the twin brothers are born loosely conjoined at the head and ever after have a somewhat mystical connection, understanding each other’s thoughts even when they’re continents apart.

What with the flashbacks and the traumatic labor, it takes narrator Marion over 100 pages to get born. That might seem like a Tristram Shandy degree of circumlocution, but there was nary a moment when my interest flagged during this book’s 50-year journey with a medical family starting in a country I knew nothing about. I was reminded of Midnight’s Children, in that the twin brothers are born loosely conjoined at the head and ever after have a somewhat mystical connection, understanding each other’s thoughts even when they’re continents apart.

When Sister Mary Joseph Praise dies in childbirth and Stone absconds, the twins are raised by the hospital’s blunt obstetrician, Hema, and her husband, a surgeon named Ghosh. Both brothers follow their adoptive parents into medicine and gain knowledge of genitourinary matters. We observe a vasectomy, a breech birth, a C-section, and the aftermath of female genital mutilation. While Marion relocates to an inner-city New York hospital, Shiva stays in Ethiopia and becomes a world expert on vaginal fistulas. The novel I kept thinking about was The Cider House Rules, which is primarily about orphans and obstetrics, and I was smugly confirmed by finding Verghese’s thanks to his friend John Irving in the acknowledgments.

Ethiopia’s postcolonial history is a colorful background, with Verghese giving a bystander’s view of the military coup against the Emperor and the rise of the Eritrean liberation movement. Like Marion, the author is an Indian doctor who came of age in Ethiopia, a country he describes as a “juxtaposition of culture and brutality, this molding of the new out of the crucible of primeval mud.” Marion’s experiences in New York City and Boston then add on the immigrant’s perspective on life in the West in the 1980s onwards.

Naomi of Consumed by Ink predicted long ago that I’d love this, and she was right. Of course I thrilled to the accounts of medical procedures, such as an early live-donor liver transplant (this was shortlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize in 2009), but that wasn’t all that made Cutting for Stone such a winner for me. I can’t get enough of sprawling Dickensian stories in which coincidences abound (“The world turns on our every action, and our every omission, whether we know it or not”), minor characters have heroic roles to play, and humor and tragedy balance each other out, if ever so narrowly. (Besides Irving, think of books like The Heart’s Invisible Furies by John Boyne.) What I’m saying, as I strive to finish this inadequate review in the last hour of the last day of the month, is that this was just my sort of thing, and I hope I’ve convinced you that it might be yours, too.

Favorite lines:

Hema: “The Hippocratic oath is if you are sitting in London and drinking tea. No such oaths here in the jungle. I know my obligations.”

“Doubt is a first cousin to faith”

“A childhood at Missing imparted lessons about resilience, about fortitude, and about the fragility of life. I knew better than most children how little separate the world of health from that of disease, living flesh from the icy touch of the dead, the solid ground from treacherous bog.”

Page count: 667

My rating:

Next month: Since Easter falls in April and I’ve been wanting to read it for ages anyway, I’ve picked out The Resurrection of Joan Ashby by Cherise Wolas to start tomorrow.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

Setting up a game of solitaire in The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz and Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

The family’s pet chicken is cooked for dinner in Coleman Hill by Kim Coleman Foote and The Snow Hare by Paula Lichtarowicz.

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A large anonymous donation to a church in Slammerkin by Emma Donoghue and Excellent Women by Barbara Pym (£10–11, which was much more in the 18th century of the former than in the 1950s of the latter).

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom.

A man throws his tie over his shoulder before eating in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Keep by Jenny Haysom. A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

A scene of self-induced abortion in Recipe for a Perfect Wife by Karma Brown and Sleeping with Cats by Marge Piercy.

Winterson does her darndest to write like Ali Smith here (no speech marks, short chapters and sections, random pop culture references). Cross Smith’s Seasons quartet with the vague aims of the Hogarth Shakespeare project and Margaret Atwood’s

Winterson does her darndest to write like Ali Smith here (no speech marks, short chapters and sections, random pop culture references). Cross Smith’s Seasons quartet with the vague aims of the Hogarth Shakespeare project and Margaret Atwood’s

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry – I read the first 76 pages. The other week two grizzled Welsh guys came to deliver my new fridge. Their barely comprehensible banter reminded me of that between Maurice and Charlie, two ageing Irish gangsters. The long first chapter is terrific. At first these fellas seem like harmless drunks, but gradually you come to realize just how dangerous they are. Maurice’s daughter Dilly is missing, and they’ll do whatever is necessary to find her. Threatening to decapitate someone’s dog is just the beginning – and you know they could do it. “I don’t know if you’re getting the sense of this yet, Ben. But you’re dealing with truly dreadful fucken men here,” Charlie warns at one point. I loved the voices; if this was just a short story it would have gotten a top rating, but I found I had no interest in the backstory of how these men got involved in heroin smuggling.

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry – I read the first 76 pages. The other week two grizzled Welsh guys came to deliver my new fridge. Their barely comprehensible banter reminded me of that between Maurice and Charlie, two ageing Irish gangsters. The long first chapter is terrific. At first these fellas seem like harmless drunks, but gradually you come to realize just how dangerous they are. Maurice’s daughter Dilly is missing, and they’ll do whatever is necessary to find her. Threatening to decapitate someone’s dog is just the beginning – and you know they could do it. “I don’t know if you’re getting the sense of this yet, Ben. But you’re dealing with truly dreadful fucken men here,” Charlie warns at one point. I loved the voices; if this was just a short story it would have gotten a top rating, but I found I had no interest in the backstory of how these men got involved in heroin smuggling. The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy – I read the first 35 pages. There’s a lot of repetition; random details seem deliberately placed as clues. I’m sure there’s a clever story in here somewhere, but apart from a few intriguing anachronisms (in 1988 a smartphone is just “A small, flat, rectangular object … lying in the road. … The object was speaking. There was definitely a voice inside it”) there is not much plot or character to latch onto. I suspect there will be many readers who, like me, can’t be bothered to follow Saul Adler from London’s Abbey Road, where he’s hit by a car in the first paragraph, to East Berlin.

The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy – I read the first 35 pages. There’s a lot of repetition; random details seem deliberately placed as clues. I’m sure there’s a clever story in here somewhere, but apart from a few intriguing anachronisms (in 1988 a smartphone is just “A small, flat, rectangular object … lying in the road. … The object was speaking. There was definitely a voice inside it”) there is not much plot or character to latch onto. I suspect there will be many readers who, like me, can’t be bothered to follow Saul Adler from London’s Abbey Road, where he’s hit by a car in the first paragraph, to East Berlin. There’s only one title from the Booker shortlist that I’m interested in reading: Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. I’ll be reviewing it later this month as part of a blog tour celebrating the Aké Book Festival, but as a copy hasn’t yet arrived from either the publisher or the library I won’t have gotten far into it before the Prize announcement.

There’s only one title from the Booker shortlist that I’m interested in reading: Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. I’ll be reviewing it later this month as part of a blog tour celebrating the Aké Book Festival, but as a copy hasn’t yet arrived from either the publisher or the library I won’t have gotten far into it before the Prize announcement.

*However, I was delighted to find a copy of her 1991 novel, Varying Degrees of Hopelessness (just 182 pages, with short chapters often no longer than a paragraph and pithy sentences) in a 3-for-£1 sale at our local charity warehouse. Isabel, a 31-year-old virgin whose ideas of love come straight from the romance novels of ‘Babs Cartwheel’, hopes to find Mr. Right while studying art history at the Catafalque Institute in London (a thinly veiled Courtauld, where Ellmann studied). She’s immediately taken with one of her professors, Lionel Syms, whom she dubs “The Splendid Young Man.” Isabel’s desperately unsexy description of him had me snorting into my tea:

*However, I was delighted to find a copy of her 1991 novel, Varying Degrees of Hopelessness (just 182 pages, with short chapters often no longer than a paragraph and pithy sentences) in a 3-for-£1 sale at our local charity warehouse. Isabel, a 31-year-old virgin whose ideas of love come straight from the romance novels of ‘Babs Cartwheel’, hopes to find Mr. Right while studying art history at the Catafalque Institute in London (a thinly veiled Courtauld, where Ellmann studied). She’s immediately taken with one of her professors, Lionel Syms, whom she dubs “The Splendid Young Man.” Isabel’s desperately unsexy description of him had me snorting into my tea:

This strange and somewhat entrancing debut novel is set in Arnott’s native Tasmania. The women of the McAllister family are known to return to life – even after a cremation, as happened briefly with Charlotte and Levi’s mother. Levi is determined to stop this from happening again, and decides to have a coffin built to ensure his 23-year-old sister can’t ever come back from the flames once she’s dead. The letters that pass between him and the ill-tempered woodworker he hires to do the job were my favorite part of the book. In other strands, we see Charlotte traveling down to work at a wombat farm in Melaleuca, a female investigator lighting out after her, and Karl forming a close relationship with a seal. This reminded me somewhat of The Bus on Thursday by Shirley Barrett and Orkney by Amy Sackville. At times I had trouble following the POV and setting shifts involved in this work of magic realism, though Arnott’s writing is certainly striking.

This strange and somewhat entrancing debut novel is set in Arnott’s native Tasmania. The women of the McAllister family are known to return to life – even after a cremation, as happened briefly with Charlotte and Levi’s mother. Levi is determined to stop this from happening again, and decides to have a coffin built to ensure his 23-year-old sister can’t ever come back from the flames once she’s dead. The letters that pass between him and the ill-tempered woodworker he hires to do the job were my favorite part of the book. In other strands, we see Charlotte traveling down to work at a wombat farm in Melaleuca, a female investigator lighting out after her, and Karl forming a close relationship with a seal. This reminded me somewhat of The Bus on Thursday by Shirley Barrett and Orkney by Amy Sackville. At times I had trouble following the POV and setting shifts involved in this work of magic realism, though Arnott’s writing is certainly striking.

The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James: A twisty, clever meta novel about “Daniel James” trying to write a biography of Ezra Maas, an enigmatic artist who grew up a child prodigy in Oxford and attracted a cult following in 1960s New York City, where he was a friend of Warhol et al. (See

The Unauthorised Biography of Ezra Maas by Daniel James: A twisty, clever meta novel about “Daniel James” trying to write a biography of Ezra Maas, an enigmatic artist who grew up a child prodigy in Oxford and attracted a cult following in 1960s New York City, where he was a friend of Warhol et al. (See

Please Read This Leaflet Carefully by Karen Havelin: A debut novel by a Norwegian author that proceeds backwards to examine the life of a woman struggling with endometriosis and raising a young daughter. I’m very keen to read this one.

Please Read This Leaflet Carefully by Karen Havelin: A debut novel by a Norwegian author that proceeds backwards to examine the life of a woman struggling with endometriosis and raising a young daughter. I’m very keen to read this one.

Sing to It: New Stories by Amy Hempel [releases on the 26th]: “When danger approaches, sing to it.” That Arabian proverb provides the title for Amy Hempel’s fifth collection of short fiction, and it’s no bad summary of the purpose of the arts in our time: creativity is for defusing or at least defying the innumerable threats to personal expression. Only roughly half of the flash fiction achieves a successful triumvirate of character, incident and meaning. The author’s passion for working with dogs inspired the best story, “A Full-Service Shelter,” set in Spanish Harlem. A novella, Cloudland, takes up the last three-fifths of the book and is based on the case of the “Butterbox Babies.” (Reviewed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)

Sing to It: New Stories by Amy Hempel [releases on the 26th]: “When danger approaches, sing to it.” That Arabian proverb provides the title for Amy Hempel’s fifth collection of short fiction, and it’s no bad summary of the purpose of the arts in our time: creativity is for defusing or at least defying the innumerable threats to personal expression. Only roughly half of the flash fiction achieves a successful triumvirate of character, incident and meaning. The author’s passion for working with dogs inspired the best story, “A Full-Service Shelter,” set in Spanish Harlem. A novella, Cloudland, takes up the last three-fifths of the book and is based on the case of the “Butterbox Babies.” (Reviewed for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.)

The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (translated from the French by Sam Taylor) [releases on the 26th]: This is a pleasant enough little book, composed of scenes in the life of a fictional chef named Mauro. Each chapter picks up with the young man at a different point as he travels through Europe, studying and working in various restaurants. If you’ve read The Heart / Mend the Living, you’ll know de Kerangal writes exquisite prose. Here the descriptions of meals are mouthwatering, and the kitchen’s often tense relationships come through powerfully. Overall, though, I didn’t know what all these scenes are meant to add up to. Kitchens of the Great Midwest does a better job of capturing a chef and her milieu.

The Cook by Maylis de Kerangal (translated from the French by Sam Taylor) [releases on the 26th]: This is a pleasant enough little book, composed of scenes in the life of a fictional chef named Mauro. Each chapter picks up with the young man at a different point as he travels through Europe, studying and working in various restaurants. If you’ve read The Heart / Mend the Living, you’ll know de Kerangal writes exquisite prose. Here the descriptions of meals are mouthwatering, and the kitchen’s often tense relationships come through powerfully. Overall, though, I didn’t know what all these scenes are meant to add up to. Kitchens of the Great Midwest does a better job of capturing a chef and her milieu.  Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others by Barbara Brown Taylor [releases on the 12th]: After she left the pastorate, Taylor taught Religion 101 at Piedmont College, a small Georgia institution, for 20 years. This book arose from what she learned about other religions – and about Christianity – by engaging with faith in an academic setting and taking her students on field trips to mosques, temples, and so on. She emphasizes that appreciating other religions is not about flattening their uniqueness or looking for some lowest common denominator. Neither is it about picking out what affirms your own tradition and ignoring the rest. It’s about being comfortable with not being right, or even knowing who is right.

Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others by Barbara Brown Taylor [releases on the 12th]: After she left the pastorate, Taylor taught Religion 101 at Piedmont College, a small Georgia institution, for 20 years. This book arose from what she learned about other religions – and about Christianity – by engaging with faith in an academic setting and taking her students on field trips to mosques, temples, and so on. She emphasizes that appreciating other religions is not about flattening their uniqueness or looking for some lowest common denominator. Neither is it about picking out what affirms your own tradition and ignoring the rest. It’s about being comfortable with not being right, or even knowing who is right.