Tag Archives: short stories

Dylan Thomas Prize Blog Tour: Things We Say in the Dark by Kirsty Logan

It’s an honour to be kicking off the official Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize 2020* blog tour with a post introducing and giving an excerpt from one of this year’s longlisted titles, the short story collection Things We Say in the Dark by Kirsty Logan.

Many of these 20 stories twist fairy tale imagery into nightmarish scenarios, enumerating fears of bodies and pregnancies going wrong. Body parts are offered as tokens of love or left behind as the sole evidence of an abduction. Ghosts and corpses are frequent presences. I also recognized some of the same sorts of Celtic sea legends that infuse Logan’s debut novel, The Gracekeepers.

Some stories are divided into multiple parts by headings or point-of-view changes. Others are in unusual formats like footnotes, a questionnaire, bullet-pointed lists, or a couple’s contrasting notes on house viewings. The titles can be like mini-tales in their own right, e.g. “Girls Are Always Hungry when All the Men Are Bite-Size” and “The Only Thing I Can’t Tell You Is Why.”

In between the stories are italicized passages that seem to give context on Logan’s composition process, including her writing retreat in Iceland – but it turns out that this is a story, too, split into pieces and shading from autobiography into fiction.

Full of magic realism and gentle horror, this is a book for fans of Salt Slow and The Doll’s Alphabet.

My favourite story was “Things My Wife and I Found Hidden in Our House,” about a series of objects Rain and her wife Alice find in the derelict house Alice’s granny has left them. Here’s an excerpt from the story to whet your appetite:

- A KNIFE

I wasn’t surprised when Alice and I found the long thin silver knife wrapped in blackened grot beneath the floorboards. It wasn’t easy: to find it we’d had to pull up just about every rotting, stinking board in the house, our hands slick with blood and filth. Alice had told me that a silver knife through the heart is the only way to kill a kelpie, so if Alice’s gran really had killed it, the knife was likely to be there somewhere. Her mistake, her haunting, was in keeping the thing. As proof? A memento? We’d never know. Then again, we knew that her bathtub drowning was due to a stroke. So I guess you can never really know anything.

Alice and I gathered up the ring and the paper and the horse and the pearls and the hair and the glass jar and the knife, and we put them all in a box. We drove for hours until we got to the coast, to the town where Alice’s gran and her grandad and the first wife had all lived, and we climbed to the highest cliff and we threw all the things into the sea.

Together we drove back to the house, holding hands between the front seats. A steady calm grew in our hearts; we knew that it was over, that we had cleansed the house and ourselves, that we had proven women’s love was stronger than women’s hate.

- MORE

Approaching the front door, key outstretched, hands still held, hearts grown sweet, Alice and I stopped. Our hands unlinked. The doorknob was wrapped all around with layers of long black hair.

My thanks to Midas PR for the free copy for review, and to Harvill Secker for permission to reprint an excerpt.

*The Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize recognizes the best published work in the English language written by an author aged 39 or under. All literary genres are eligible, so there are poetry collections nominated as well as novels and short stories. The other 11 books on this year’s longlist are:

- Surge, Jay Bernard

- Flèche, Mary Jean Chan (my review)

- Exquisite Cadavers, Meena Kandasamy

- Black Car Burning, Helen Mort

- Virtuoso, Yelena Moskovich

- Inland, Téa Obreht

- Stubborn Archivist, Yara Rodrigues Fowler (my review)

- If All the World and Love Were Young, Stephen Sexton

- The Far Field, Madhuri Vijay

- On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong

- Lot, Bryan Washington

The official blog tour runs this month and into April, with multiple bloggers covering each book. At the end of March, I’ll also be reviewing the poetry collection by Stephen Sexton.

Adventures in Rereading: A. S. Byatt and Abigail Thomas

At the end of last year, I picked out a whole shelf’s worth of books I’ve been meaning to reread. I know that others of you are devoted re-readers, returning to childhood favorites for comfort or poring over admired novels two or three times to figure out how they work. Alas, I’m usually resistant to rereading because I feel like it takes away time that I could be spending reading new or at least new-to-me books. Yet along with the nostalgia there is also a certain relief to returning to a favorite: here’s a book that is guaranteed not to disappoint.

So far this year I’ve finished two rereads, and I’m partway through a third. I’m not managing the one-every-other-week pace I would need to keep up to get through the whole shelf this year, but for me this is still good progress. I’ll report regularly on my experience of rereading.

The Matisse Stories by A. S. Byatt (1993)

Byatt is my favorite author. My memory for individual short stories is pitiful, yet I have never forgotten the first of three stories in this volume, so I focus on it here with a close rereading. In “Medusa’s Ankles,” a middle-aged woman goes berserk in a hair salon but it all turns out fine. I remember imagining what that would be like: to let go, to behave badly with no thought for others’ opinions, to act purely on instinct – and for there to be no consequences.

I’d forgotten all the particulars of the event. Susannah, a linguist, is drawn to the salon by the Rosy Nude reproduction she sees through the window. She becomes a reluctant receptacle for her stylist Lucian’s stories, including tales of his wife’s fat ankles and his mistress’ greater appeal. He confides in her his plan to run away. “I don’t want to put the best years of my life into making suburban old dears presentable. I want something more.”

Susannah holds in all her contempt for Lucian and his hip shop redesign until the day he fobs her off on another stylist – even though she’s said she needs an especially careful job this time because she is to appear on TV to accept the Translator’s Medal. When Deirdre is done, Susannah forgets about English politeness and says just what she thinks: “It’s horrible. I look like a middle-aged woman with a hair-do.” (Never mind that that’s exactly what she is.)

Susannah holds in all her contempt for Lucian and his hip shop redesign until the day he fobs her off on another stylist – even though she’s said she needs an especially careful job this time because she is to appear on TV to accept the Translator’s Medal. When Deirdre is done, Susannah forgets about English politeness and says just what she thinks: “It’s horrible. I look like a middle-aged woman with a hair-do.” (Never mind that that’s exactly what she is.)

In a whirlwind of fury, she trashes the salon. Byatt describes the aftermath, indulging her trademark love of colors: “It was a strange empty battlefield, full of glittering fragments and sweet-smelling rivulets and puddles of venous-blue and fuchsia-red unguents, patches of crimson-streaked foam and odd intense spills of orange henna or cobalt and copper.”

You can just imagine the atmosphere in the salon: everyone exchanging horrified looks and cautiously approaching Susannah as if she’s a dangerous dog. Lucian steps in to reassure her: “We all feel like that, sometimes. Most of us don’t dare. … The insurance’ll pay. Don’t worry. … You’ve done me a good turn in a way.” Maybe he’ll go off with his girlfriend and start a new business, after all. Predictably, the man has made it all about him.

The ironic kicker to this perfect story about middle age and female rage comes after Susannah goes home to a husband we hadn’t heard about yet. “He saw her. (Usually he did not.) ‘You look different. You’ve had your hair done. I like it. You look lovely. It takes twenty years off you. You should have it done more often.’”

“Art Work” briefly, unnecessarily, uses a Matisse painting as a jumping-off point. A bourgeois couple, a painter and magazine design editor, hire Mrs. Brown, a black woman, to clean their house and are flabbergasted when she turns out to be an artist in her own right. “The Chinese Lobster,” the final story, is the only one explicitly about Matisse. An academic dean invites her colleague out to lunch at a Chinese restaurant to discuss a troubled student he’s supervising. This young woman has eating disorders and is doing a portfolio of artwork plus a dissertation on Matisse’s treatment of female bodies. Her work isn’t up to scratch, and now she’s accused her elderly supervisor of sexual harassment. The racial and sexual politics of these two stories don’t quite hold up, though both are well constructed.

I reread the book in one morning sitting last week.

My original rating (c. 2005):

My rating now:

A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas (2006)

In April 2000 Thomas’s husband Rich was hit by a car and incurred a traumatic brain injury when their dog Harry got off the leash and Rich ran out into the road near their New York City home to save him. It was a miracle that Rich lived, but his disability was severe enough that he had to be moved to an upstate nursing home. This is one of the first memoirs I ever remember reading, and it made a big impression. I don’t think I realized at the time that it was written in discrete essays, many of which were first published in magazines and anthologies. It represents an advance on the highly fragmentary nature of her first memoir, Safekeeping.

Thomas maintains a delicate balance of emotions: between guilt every time she bids Rich goodbye in the nursing home and relief that she doesn’t have to care for him 24/7; between missing the life they had and loving the cozy one she’s built on her own with her three dogs. (The title is how Aborigines refer to the coldest nights.) As in One Hundred Names for Love and All Things Consoled, Rich’s aphasia produces moments of unexpectedly poetic insight.

Thomas maintains a delicate balance of emotions: between guilt every time she bids Rich goodbye in the nursing home and relief that she doesn’t have to care for him 24/7; between missing the life they had and loving the cozy one she’s built on her own with her three dogs. (The title is how Aborigines refer to the coldest nights.) As in One Hundred Names for Love and All Things Consoled, Rich’s aphasia produces moments of unexpectedly poetic insight.

Before rereading I remembered one phrase and one incident (though I’d thought the latter was from Safekeeping): doctors described Rich’s skull as “shattered like an eggshell,” and Thomas remembers a time she was driving and saw the car ahead hit a raccoon; she automatically swerved to avoid the animal, but saw in her rearview mirror that it was still alive and realized the compassionate thing would have been to run it over again. I’ve never forgotten these disturbing images.

Unassuming and heart on sleeve, Thomas wrote one of the most beautiful books out there about loss and memory. I’d recommend this to fans of Anne Lamott and readers of bereavement memoirs in general. This is what I wanted from the rereading experience: to find a book that was even better the second time around.

My original rating (c. 2006):

My rating now:

Currently rereading: Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes

Considering rereading next: On Beauty by Zadie Smith

Done any rereading lately?

Tenth of December by George Saunders

Even before George Saunders won the Man Booker Prize for the truly astounding Lincoln in the Bardo, I wanted to read Tenth of December (2013), the short story collection that won him the inaugural Folio Prize. The 10 stories, set in a recognizable contemporary or near-future suburban America, feature a mixture of realist and science fiction scenarios and a gently satirical tone.

At times the narration seems to reflect a new form of human speech, almost like shorthand, with the characters only lapsing into old-fashioned garrulousness under the influence of specially designed pharmaceuticals. I found the language most amusing in “The Semplica Girl Diaries,” narrated by a lower-middle-class dad who’s trying to keep up with the Joneses and please his daughters. “Have to do better! Be kinder. Start now. Soon they will be grown and how sad, if only memory of you is testy stressed guy in bad car.”

At times the narration seems to reflect a new form of human speech, almost like shorthand, with the characters only lapsing into old-fashioned garrulousness under the influence of specially designed pharmaceuticals. I found the language most amusing in “The Semplica Girl Diaries,” narrated by a lower-middle-class dad who’s trying to keep up with the Joneses and please his daughters. “Have to do better! Be kinder. Start now. Soon they will be grown and how sad, if only memory of you is testy stressed guy in bad car.”

However, notably absent from the entertaining definitions he drops in for posterity (Whac-a-Mole, in case future readers are unfamiliar: “Plastic mole emerges, you whack with hammer, he dies, falls, another emerges, you whack, kill?”) is one for the SGs. Only gradually do you realize, with some horror, that “Semplica girls,” who have left the developing world for a chance at a better life, are a trendy lawn ornament, strung along a wire through their brains. From this article, included as an introduction to the Bloomsbury paperback, I learned that this story arose from a dream Saunders had. That accounts for how matter-of-factly bizarre it is.

Although it runs a bit long, this story was one of my favorites, along with “Victory Lap,” about a geeky high schooler improbably saving a classmate from a sexual assault, and “Sticks,” which in under two pages captures a family’s entire decades-long dynamic. None of the rest were quite as memorable for me, so I’m not sure I’ll seek out more of Saunders’s stories. I just couldn’t resist the urge to read and review this book in time for the day in the title after I found it on clearance at my local Waterstones.

My rating:

Young Writer of the Year Award: Shortlist Reviews and Predictions

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a bookish highlight of 2017 for me. I’m pleased for this year’s shadow panelists, a couple of whom are blogging friends (one I’ve met IRL), to have had the same opportunity, and I look forward to attending the prize ceremony at the London Library on December 5th.

I happened to have already read two of the shortlisted titles, the poetry collection The Perseverance by Raymond Antrobus and the debut novel Stubborn Archivist by Yara Rodrigues Fowler, which was one of my specific wishes/predictions. The kind folk of FMcM Associates sent me the other two shortlisted books, a short story collection and another debut novel, for blog reviews so that I could follow along with the shadow panel’s deliberations.

Salt Slow by Julia Armfield (2019)

These nine short stories are steeped in myth and magic, but often have a realistic shell. Only gradually do the fantastical or dystopian elements emerge, with the final paragraph delivering a delicious surprise. For instance, the narrator of “Mantis” attends a Catholic girls’ school and is caught up in a typical cycle of self-loathing and obsessing over boys. It’s only at the very end that we realize her extreme skin condition is actually a metamorphosis that enables her to protect herself. The settings are split between the city and the seaside; the perspective is divided almost perfectly down the middle between the first and third person. The body is a site of transformation, or a source of grotesque relics, as in “The Collectables,” in which a PhD student starts amassing body parts she could only have acquired via grave-robbing.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection.

Armfield’s prose is punchy, with invented verbs and condensed descriptions that just plain work: “Jenny had taken to poltergeisting round the house”; “skin like fork-clawed cottage cheese,” “the lobster shells gleam a slick vermilion” and “The sky is gory with stars.” There’s no shortage of feminist fantasy stories out there nowadays – Aimee Bender, Kelly Link, Carmen Maria Machado and Karen Russell are just a few others working in this vein – but the writing in Salt Slow really grabbed me even when the plots didn’t. I’ll be following Armfield’s career with interest.

Testament by Kim Sherwood (2018)

Eva Butler is a 24-year-old MA student specializing in documentary filmmaking. She is a live-in carer for her grandfather, the painter Joseph Silk (real name: József Zyyad), in his Fitzroy Park home. When Silk dies early on in the book, she realizes that she knows next to nothing about his past in Hungary. Learning that he wrote a testament about his Second World War experiences for the Jewish Museum in Berlin, she goes at once to read it and is distressed at what she finds. With the help of Felix, the museum’s curator, who did his PhD on Silk’s work, she travels to Budapest to track down the truth about her family.

Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

It’s almost impossible to write anything new about the Holocaust these days, and overfamiliarity was certainly a roadblock for me here. I was especially reminded of Julie Orringer’s The Invisible Bridge, what with its focus on the Hungarian Jewish experience. However, I did appreciate the way Sherwood draws on her family history – her grandmother is a Hungarian Holocaust survivor – to consider how trauma still affects the second and third generation. This certainly doesn’t feel like a debut novel. It’s highly readable, and the emotional power of the story cannot be denied. The Young Writer of the Year Award is great for highlighting books that risk being overlooked: in a year dominated by The Testaments, poor Testament was otherwise likely to sink without notice.

Note: “Testament” is also the title of the poem written by Sherwood’s great-grandfather that she recited at her grandfather’s funeral – just as Eva does in the novel. It opens this Telegraph essay (paywalled, but reprinted in the paperback of Testament) that Sherwood wrote about her family history.

General thoughts and predictions:

Any of these books would be a worthy winner. However, as Raymond Antrobus has already won this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize as well as the 2018 Geoffrey Dearmer Award from the Poetry Society, The Perseverance has had sufficient recognition – plus it’s a woman’s turn. Testament is accomplished, and likely to hold the widest appeal, but it strikes me as the safe choice. Salt Slow would be an edgier selection, and feels quite timely and fresh. But Stubborn Archivist has stuck with me since I reviewed it in March. I called it “Knausgaard for the Sally Rooney generation” and wrote that “the last book to have struck me as truly ‘novel’ in the same way was Lincoln in the Bardo.” From a glance at the shadow panel’s reviews thus far, I fear it may prove too divisive for them, though.

Based on my gut instincts and a bit of canny thinking about the shadow panelists and judges, here are my predictions:

Shadow Panel:

- What they will pick: Testament [but they might surprise me and go with Salt Slow or Stubborn Archivist]

- What they should pick: Salt Slow

Official Judging Panel:

- What they will pick: Stubborn Archivist [but they might surprise me and go with Salt Slow]

- What they should pick: Stubborn Archivist

I understand that the shadow panel is meeting today for their in-person deliberations. I wish them luck! Their pick will be announced on the 28th. I’ll be intrigued to see which book they select, and how it compares with the official winner on December 5th.

Have you read anything from this year’s shortlist?

Getting Real about My “Set Aside Temporarily” Shelf

Mid-November, and I’ve been thinking about how many of the books I currently have on the go I will be able to finish before the end of the year – not to mention whether I can squeeze in any more 2019 releases, or get a jump on early 2020 releases (ha!).

In the back of my mind, however, is some mild, self-induced anxiety. You see, the other year I started an exclusive Goodreads shelf (i.e., one that doesn’t fall into one of the three standard categories, “Read,” “Currently Reading” or “Want to Read”) called “Set Aside Temporarily,” on which I place a book I have put on hiatus for whatever reason, whether I’d read a handful of pages or 200. Maybe a few library holds came in that I needed to finish before a strict due date, or I took on a last-minute review assignment and needed to focus on that book instead.

Usually, though, it’s just a case of having started too many books at once. I’m addicted to finishing books, but also to starting them – often a fresh stack of four or five in one sitting, to add to my 10 or more already on the go. I always used to say that I read 10‒15 books at a time, but in the latter half of this year that has crept up to 20‒25. Sometimes I can manage it; other times it feels like too much, and a few books from the stack fall by the wayside and get stuck with that polite label of “set aside.” It doesn’t necessarily mean that I wasn’t enjoying them, just that they were less compelling than some other reads.

Some of my “set aside” reads, stacked up next to my reading armchair.

So as I contemplated this virtual shelf, which as of the 12th had 33 titles on it, I figured I have the following alternatives for each book: pick it back up immediately and finish it as soon as possible, ideally this year (especially if it’s a 2019 release, so it can be in the running for my Best Of lists); regretfully mark it as a DNF; put it back on the shelf, with or without a place marker, to read some other time; skim to the end if I wasn’t getting on with it particularly well yet want to know what happens; or keep it in limbo for now and maybe read it in 2020.

I told myself it was decision time on all of these. Here’s how it played out:

(* = 2019 release)

Currently reading:

- Let’s Hope for the Best by Carolina Setterwall*

- Savage Pilgrims: On the Road to Santa Fe by Henry Shukman

To resume soon:

- The Easternmost House by Juliet Blaxland* (as soon as my library hold comes in)

- Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner*

- The Spirit of Christmas: Stories, Poems, Essays by G.K. Chesterton

- The River Capture by Mary Costello*

- The Scar by Mary Cregan*

- The Envoy from Mirror City by Janet Frame

- Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country by Pam Houston*

- Two-Part Invention: The Story of a Marriage by Madeleine L’Engle

- The Way through the Woods: Of Mushrooms and Mourning by Long Litt Woon*

- Kinds of Love by May Sarton

- All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf by Katharine Smyth*

- Dancing with Bees by Brigit Strawbridge Howard*

- A Three Dog Life by Abigail Thomas (a re-read)

- The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall*

DNFed:

- The Manticore by Robertson Davies – A different perspective isn’t enough to keep me interested in a recounting of the events from Fifth Business.

- The Dovekeepers by Alice Hoffman (even though I’d read 250 pages of the danged thing) – Painstaking but worthy historical fiction.

- Then She Found Me by Elinor Lipman – The first 100 or so pages were pleasant reading during a beer festival, but I had no impetus to pick it up afterwards.

- A Door in the Earth by Amy Waldman* – The first 12% didn’t grab me. Never say never, but I don’t plan on picking it back up soon. Sad, as this was one of my most anticipated releases of the year.

- The Voyage Out by Virginia Woolf – I really tried. It was the third Woolf novel I’d picked up (and put down) in quick succession this year. She’s just such hard work.

Returned to the shelf for another time:

- Ship Fever by Andrea Barrett

- Emerald City by Jennifer Egan

- The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr

- Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee

- Wait Till I Tell You by Candia McWilliam

- The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton

- Full Tilt: Ireland to India with a Bicycle by Dervla Murphy

- A Few Short Notes on Tropical Butterflies by John Murray

- Saint Maybe by Anne Tyler

To skim:

- The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom* – Although very well written, this is dense with family detail, more than I really need.

Still set aside:

- In the Springtime of the Year by Susan Hill – to finish off next spring!

- Bodies in Motion and at Rest: On Metaphor and Mortality by Thomas Lynch (a university library book) – It’s in discrete essays so can be picked up and put down at will.

Some general observations: Recently I’ve lacked staying power with short story collections. However, I find it’s not usually a problem to read a few stories (or essays) and then return to a collection some months later. Memoirs, travel books and quiet fiction can also withstand an interruption. If I’ve put aside a plotty or style-heavy novel, however, that’s a bad sign that I will probably end up DNFing it.

Do you have a physical or virtual shelf of books that are partly read and languishing? How have you tackled it in the past?

Novellas in November, Part 1: 3 Nonfiction, 2 Super-Short Fiction

Short books; short reviews.

Nonfiction:

The Measure of My Days by Florida Scott-Maxwell (1968)

[150 pages]

I learned about this from one of May Sarton’s journals, which shares its concern with ageing and selfhood. The author was an American suffragist, playwright, mother and analytical psychologist who trained under Jung and lived in England and Scotland with her Scottish husband. She kept this notebook while she was 82, partly while recovering from gallbladder surgery. It’s written in short, sometimes aphoristic paragraphs. While I appreciated her thoughts on suffering, developing “hardihood,” the simplicity that comes with giving up many cares and activities, and the impossibility of solving “one’s own incorrigibility,” I found this somewhat rambly and abstract, especially when she goes off on a dated tangent about the equality of the sexes. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

I learned about this from one of May Sarton’s journals, which shares its concern with ageing and selfhood. The author was an American suffragist, playwright, mother and analytical psychologist who trained under Jung and lived in England and Scotland with her Scottish husband. She kept this notebook while she was 82, partly while recovering from gallbladder surgery. It’s written in short, sometimes aphoristic paragraphs. While I appreciated her thoughts on suffering, developing “hardihood,” the simplicity that comes with giving up many cares and activities, and the impossibility of solving “one’s own incorrigibility,” I found this somewhat rambly and abstract, especially when she goes off on a dated tangent about the equality of the sexes. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit (2004)

[143 pages]

“Activism is not a journey to the corner store, it is a plunge into the unknown. The future is always dark.” This resonated with the Extinction Rebellion handbook I reviewed earlier in the year. Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. At first I thought it depressing that 15 years on we’re still dealing with many of the issues she mentions here, and the environmental crisis has only deepened. But her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

“Activism is not a journey to the corner store, it is a plunge into the unknown. The future is always dark.” This resonated with the Extinction Rebellion handbook I reviewed earlier in the year. Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. At first I thought it depressing that 15 years on we’re still dealing with many of the issues she mentions here, and the environmental crisis has only deepened. But her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Lama by Derek Tangye (1966)

[160 pages]

Tangye wrote a series of cozy animal books similar to Doreen Tovey’s. He and his wife Jean ran a flower farm in Cornwall and had a succession of cats, along with donkeys and a Muscovy duck named Boris. After the death of their beloved cat Monty, Jean wanted a kitten for Christmas but Tangye, who considered himself a one-cat man rather than a wholesale cat lover, hesitated. The matter was decided for them when a little black stray started coming round and soon made herself at home. (Her name is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s safe flight from Tibet.) Mild adventures ensue, such as Lama going down a badger sett and Jeannie convincing herself that she’s identified another stray as Lama’s mother. Pleasant, if slight; I’ll read more by Tangye. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Tangye wrote a series of cozy animal books similar to Doreen Tovey’s. He and his wife Jean ran a flower farm in Cornwall and had a succession of cats, along with donkeys and a Muscovy duck named Boris. After the death of their beloved cat Monty, Jean wanted a kitten for Christmas but Tangye, who considered himself a one-cat man rather than a wholesale cat lover, hesitated. The matter was decided for them when a little black stray started coming round and soon made herself at home. (Her name is a tribute to the Dalai Lama’s safe flight from Tibet.) Mild adventures ensue, such as Lama going down a badger sett and Jeannie convincing herself that she’s identified another stray as Lama’s mother. Pleasant, if slight; I’ll read more by Tangye. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Fiction:

The Small Miracle by Paul Gallico (1951)

[47 pages]

Like Tangye, Gallico is known for writing charming animal books, but fables rather than memoirs. Set in postwar Assisi, Italy, this stars Pepino, a 10-year-old orphan boy who runs errands with his donkey Violetta to earn his food and board. When Violetta falls ill, he dreads losing not just his livelihood but also his only friend in the world. But the powers that be won’t let him bring her into the local church so that he can pray to St. Francis for her healing. Pepino takes to heart the maxim an American corporal gave him – “don’t take no for an answer” – and takes his suit all the way to the pope. This story of what faith can achieve just manages to avoid being twee. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Like Tangye, Gallico is known for writing charming animal books, but fables rather than memoirs. Set in postwar Assisi, Italy, this stars Pepino, a 10-year-old orphan boy who runs errands with his donkey Violetta to earn his food and board. When Violetta falls ill, he dreads losing not just his livelihood but also his only friend in the world. But the powers that be won’t let him bring her into the local church so that he can pray to St. Francis for her healing. Pepino takes to heart the maxim an American corporal gave him – “don’t take no for an answer” – and takes his suit all the way to the pope. This story of what faith can achieve just manages to avoid being twee. (From Kennet Centre free bookshop)

Birthday Girl by Haruki Murakami (2002; English translation by Jay Rubin, 2003)

[42 pages]

Reprinted as a stand-alone pamphlet to celebrate the author’s 70th birthday, this is about a waitress who on her 20th birthday is given the unwonted task of taking dinner up to the restaurant owner, who lives above the establishment. He is taken with the young woman and offers to grant her one wish. We never hear exactly what that wish was. It’s now more than 10 years later and she’s recalling the occasion for a friend, who asks her if the wish came true and whether she regrets what she requested. She surveys her current life and says that it remains to be seen whether her wish will be fulfilled; I could only assume that she wished for happiness, which is shifting and subjective. Encountering this in a larger collection would be fine, but it wasn’t particularly worth reading on its own. (Public library)

Reprinted as a stand-alone pamphlet to celebrate the author’s 70th birthday, this is about a waitress who on her 20th birthday is given the unwonted task of taking dinner up to the restaurant owner, who lives above the establishment. He is taken with the young woman and offers to grant her one wish. We never hear exactly what that wish was. It’s now more than 10 years later and she’s recalling the occasion for a friend, who asks her if the wish came true and whether she regrets what she requested. She surveys her current life and says that it remains to be seen whether her wish will be fulfilled; I could only assume that she wished for happiness, which is shifting and subjective. Encountering this in a larger collection would be fine, but it wasn’t particularly worth reading on its own. (Public library)

I’ve also had a number of novella DNFs so far this month, alas: Atlantic Winds by William Prendiville (not engaging in the least), By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept by Elizabeth Smart (fascinating autobiographical backstory; pretentious prose) and The Dream Life of Balso Snell by Nathanael West (even more bizarre and crass than I’m used to from him).

Onwards!

Have you read any of these novellas? Which one takes your fancy?

Humiliation: Stories by Paulina Flores

Paulina Flores, a young Chilean author and high school teacher, won the Roberto Bolaño Short Story Prize for the title story in her debut collection. These nine stories are about how we relate to the past, particularly our childhood – whether with nostalgia or regret – and about the pivotal moments that stand out in the memory. The first two, “Humiliation” and “Teresa,” I previewed in one of my Women in Translation Month posts. They feature young fathers and turn on a moment of surprise: An unemployed father takes his two daughters along to his audition; a college student goes home with a single father for a one-night stand.

Of the rest, my favorites were “Talcahuano,” about teenage friends whose plan to steal musical instruments from the local evangelical church goes awry when there’s a crisis with the narrator’s father, a laid-off marine (readalike: Sweet Sorrow by David Nicholls); and “Forgetting Freddy,” in which a young woman who ends up back in her mother’s apartment after a breakup listens to the neighbors fighting and relives childhood fears during her long baths (readalike: History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund).

Of the rest, my favorites were “Talcahuano,” about teenage friends whose plan to steal musical instruments from the local evangelical church goes awry when there’s a crisis with the narrator’s father, a laid-off marine (readalike: Sweet Sorrow by David Nicholls); and “Forgetting Freddy,” in which a young woman who ends up back in her mother’s apartment after a breakup listens to the neighbors fighting and relives childhood fears during her long baths (readalike: History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund).

“American Spirit” recalls two friends’ time waitressing (readalike: Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler), and in “Last Vacation” a young man recounts his last trip to La Serena with his aunt before everything went wrong for his family. “Laika” is a troubling one in that the protagonist remembers her childhood brush with pedophilia not with terror or disgust but with a sort of fondness. A number of the stories conclude that you can’t truly remake your life, nor can you escape the memories that have shaped you – even if you might like to.

A fairly common feature in story volumes is closing with a novella. Almost invariably, I like these long stories the least, and sometimes skip them. Here, the 72-page “Lucky Me” could easily be omitted. Denise, a librarian who watches porn and reads the Old Testament in her spare time (“what she needed was to feel something. She needed pleasure and spirituality”), lets the upstairs neighbor use her bedroom for sex; Nicole, a fourth-grader, has her world turned upside down when her best friend’s mother becomes their housekeeper. Although the story brings its strands, one in the first person and one in the third (giving the book an even 4.5/4.5 split), together in a satisfying manner, it was among my least favorites in the collection.

Overall, though, these are sharp and readable stories I can give a solid recommendation.

My rating:

Humiliation (2016; English translation by Megan McDowell, 2019) is published by Oneworld today, November 7th,; it came out on the 5th from Catapult in the USA. My thanks to Margot Weale for a proof copy for review.

Ake Book Festival: An Extract from Manchester Happened

Africa’s leading literary festival, Ake Book Festival in Lagos, Nigeria, is in its seventh year. Appearing this year are 100 authors including Ayobami Adebayo, Oyinkan Braithwaite, Reni Eddo-Lodge, Bernadine Evaristo, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi and Nnedi Okarafor. I was asked to take part in a blog tour celebrating the festival and the authors involved – specifically, to host an extract of Makumbi’s Manchester Happened, which I’ve been especially keen to read since hearing her in conversation with Evaristo last week.

This is the opening few pages of “Our Allies the Colonies,” the first story following the Prologue. I hope it whets your appetite to read the whole thing.

First he felt a rush of dizziness like life was leaving his body, then the world wobbled. Abbey stopped and held onto a bollard outside the Palace Theatre. He had not eaten all day. He considered nipping down to Maama Rose’s for fried dumplings and kidney beans, but the thought of eating brought nausea to his throat. He steered his mind away from food. He gave himself some time then let go of the bollard to test his steadiness. His head felt right, and his vision was back. He started to walk tentatively at first then steadily, down Oxford Road, past the Palace Hotel, under the train bridge, upwards, towards the Grosvenor Picture Palace.

Abbey was set to return to Uganda. He had already paid for the first leg of the journey – the passage from Southampton to Mombasa – and was due to travel within six months. For the second and third legs of the journey – Mombasa to Nairobi, then Nairobi to Kampala – he would pay at the ticket offices on arrival. He had saved enough to start a business either dealing in kitenge textiles from the Belgian Congo or importing manufactured goods from Mombasa. Compete with the Indians even. As a starter, he had bought rolls of fabric prints from Summer Mist Textiles for women’s dresses and for men’s suits, to take with him. All that commercial development in Uganda he had read about – increased use of commercial vehicles; the anticipated opening of the Owen Falls Dam, which would provide electricity for everyone; he had even heard that Entebbe had opened an airport back in 1951 – was beckoning.

But his plan was in jeopardy. It was his one-month-old baby, Moses. Abbey had just returned from Macclesfield Children’s Home, where the baby’s mother, Heather Newton, had given him up for adoption, but he had not seen his son. In fact, he did not know what the baby looked like: he never saw him in hospital when he was born. Abbey suspected that Heather feared that one day she might bump into him and Moses. But Heather was fearful for nothing. Abbey was taking Moses home, never to return.

Suppose the children’s home gave you the child, what then, hmm? the other side of his mind asked. What do you know about babies? The journey from Southampton to Mombasa is at least two weeks long on a cheap vessel. The bus ride from Mombasa to Nairobi would last up to two days. Then the following night you would catch the mail train from Nairobi to Kampala: who knows if it is still running? All those journeys with luggage and a six-month-old ankle-biter on your own. Yet Abbey knew that if he left Britain without his boy, that would be it. Moses would be adopted, given a new name and there would be no way of finding him. Then his son would be like those rootless Baitale children you heard of in Toro, whose Italian fathers left them behind.

He was now outside Manchester Museum, by the university. He was on his way to his second job, at the Princess Road bus depot, where he cleaned Manchester Corporation buses. His shift began at 9 p.m. It was almost 8 p.m., but the day was bright. He could not wait to get home and tell people how in Britain the sun had moods. It barely retired in summer yet in winter it could not be bothered to rise. He could not wait to tell them things about Britain. It was a shame he had stayed this long. But having a job and saving money made him feel like he was not wasting his youth away in a foreign land. His day job paid the bills while the evening job put savings away in his Post Office account. His mind turned on him again: Maybe Heather had a point – you don’t have a wife to look after Moses while you work. You still have five months before you set off; if the home gives him to you, how will you look after him? But then shame rose and reason was banished. Blood is blood, a child is better off with his father no matter what.

He reached Whitworth Park. It was packed with people sunning themselves, young men throwing and catching Frisbees, families picnicking. At the upper end, close to Whitworth Art Gallery, he caught sight of a group of Teddy boys who, despite the warm evening, wore suits, crêpe-soled shoes and sunglasses, their greased hair slicked back. They looked like malnourished dandies. Even though Teddy Boys tended to hunt blacks in the night, Abbey decided against crossing the park. Instead, he walked its width to Moss Lane East. The way the sun had defrosted British smiles. ‘Enjoy it while it lasts,’ strangers will tell you now.

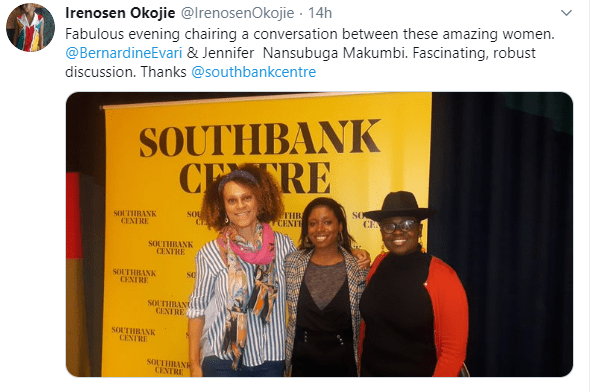

Bernardine Evaristo and Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi in Conversation

Through a giveaway on Eric’s blog, I won tickets to see Bernardine Evaristo and Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi speak about their latest books at the London Literature Festival (this year’s theme: “Once Upon Our Times”) at the Southbank Centre yesterday. It was great to meet up with fellow bloggers Eric and Eleanor to hear these two black women writers read from their recent work and discuss feminism, the political landscape for writers of African descent, and their experiments with form.

Frustrated by the lack of black women in British literature, Evaristo started writing Girl, Woman, Other in 2013. She began with Carole (Anglo-Nigerian, like herself), who has to change to fit in, first at Oxford and then as a City banker. Next she moved on to the stories of Carole’s mother and school friend, and the book grew from there. All told, there are four mother–daughter pairs. Evaristo believes her background as an actress (in her twenties) allowed her to almost become these characters and write them from the inside, so that even though the chapters are written in the third person they feel like first-person narratives. The 12 flawed, complex main characters are “equal protagonists,” she insisted. Her aim was “to explore multiplicity to address our invisibility.” She characterizes the book’s style as “fusion fiction”: an accessible take on the experimental novel, with unorthodox, free-flowing language that allows readers to move easily between the different characters’ storylines.

Both Evaristo and Makumbi admitted to having a complicated relationship with feminism, Evaristo because the feminism of the 1980s did not seem to include black women and Makumbi because the fight for equality is still ongoing in patriarchal African societies like her native Uganda’s. Evaristo feels that feminism is now more inclusive and, also thanks to the #MeToo movement, there has been a place for her book that may not have been there five or 10 years ago. (The same goes for Makumbi, who has only now found a publisher for her very feminist first novel, which was rejected in the 2000s.) Both authors spoke of the ways in which people are made to feel “Other”: through sex, race and class. Makumbi pointed out that Africans experience a specific racism separate from other blacks in Britain. “I’m not racist, but I draw the line at Africans” is how she caricatured this view.

Makumbi’s novel Kintu is a sprawling family saga that has been compared to Roots, but she has recently released a collection of short stories that focus on Ugandan immigration to Britain between the 1950s and today. She envisioned Manchester Happened as “a letter back home” to tell people what it’s really like to settle in a new country, as well as a chance to reflect on the underrepresented East African immigration experience. Much of the book is drawn from her life, such as working as an airport security officer to fund her creative writing degree. Her mentor recommended that she start writing stories as a way to counterbalance the intensity of Kintu – a chance to see the beginning, middle and end as a simple arc. She assumed short stories would be easier than a novel, yet her first story took her four years to write. It is as if she can only look into her past for brief moments, anyway, she explained, so the story form has been perfect. She has deliberately avoided the negativity of many migration narratives, she said: Things have in fact gone well for her, and we’ve heard about things going wrong many times before.

Makumbi’s novel Kintu is a sprawling family saga that has been compared to Roots, but she has recently released a collection of short stories that focus on Ugandan immigration to Britain between the 1950s and today. She envisioned Manchester Happened as “a letter back home” to tell people what it’s really like to settle in a new country, as well as a chance to reflect on the underrepresented East African immigration experience. Much of the book is drawn from her life, such as working as an airport security officer to fund her creative writing degree. Her mentor recommended that she start writing stories as a way to counterbalance the intensity of Kintu – a chance to see the beginning, middle and end as a simple arc. She assumed short stories would be easier than a novel, yet her first story took her four years to write. It is as if she can only look into her past for brief moments, anyway, she explained, so the story form has been perfect. She has deliberately avoided the negativity of many migration narratives, she said: Things have in fact gone well for her, and we’ve heard about things going wrong many times before.

I’m over halfway through Girl, Woman, Other now, and enjoying it very much – but wondering if its breadth sacrifices some depth. Evaristo acknowledged that she felt a bit less attached to these characters than she has in novels where she followed just one or two characters all the way through. Still, she feels that she knows and understands these women, even if she doesn’t like or approve of all of them. She read excerpts from the sections about Yazz, a feisty and opinionated young woman waiting for her mother’s play to start, and Hattie, a strong-willed 93-year-old from a Northumberland farming family. Makumbi read from two stories, one about a Ugandan couple arriving in Manchester in 1950 and the other set in the airport security area. In the latter the protagonist confiscates a whip from a priest, a funny moment that seems to represent Makumbi’s style – moderator Irenosen Okojie, a Nigerian author, mentioned another notable story from the perspective of a Ugandan street dog newly pampered in Britain.

I hope to read Manchester Happened soon, and should be featuring an extract from it next week as part of the Ake Book Festival blog tour. I’ll also finish the Evaristo this week and expect it to be on my Best of 2019 fiction list.

Short Story Collections Read Recently

This is the fourth year in a row that I’ve made a concerted effort to read more short stories in the alliterative month of September. (See also my 2016, 2017 and 2018 performances.) Short story collections are often hit and miss for me, and based on a few recent experiences I seem to be prone to DNFing them after two stories – when I’ve had my fill of the style and content. I generally have better luck with linked stories like Olive Kitteridge and its sequel, because they rely on a more limited set of characters and settings, and you often get intriguingly different perspectives on the same situations.

So far this year, I’ve read just five story collections – though that rises to 13 if I count books of linked short stories that are often classed as novels (Barnacle Love, Bottled Goods, Jesus’ Son, The Lager Queen of Minnesota, Olive Kitteridge, Olive, Again, That Time I Loved You and The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards). Twelve is my minimum goal for short story collections in a year – the equivalent of one per month – so I’m pleased to have surpassed that, and will continue to pick up the occasional short story collection as the year goes on.

The first two books I review here were hits with me, while the third disappointed me a bit.

The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher by Hilary Mantel (2014)

Four of these 10 stories first appeared in the London Review of Books, and another four in the Guardian. Most interestingly, the opening story, “Sorry to Disturb,” about a bored housewife trying to write a novel while in Saudi Arabia with her husband in 1983–4, was published in the LRB with the subtitle “A Memoir.” That it’s one of the best few ‘stories’ here doesn’t negate Mantel’s fictional abilities so much as prove her talent for working in the short form.

Four of these 10 stories first appeared in the London Review of Books, and another four in the Guardian. Most interestingly, the opening story, “Sorry to Disturb,” about a bored housewife trying to write a novel while in Saudi Arabia with her husband in 1983–4, was published in the LRB with the subtitle “A Memoir.” That it’s one of the best few ‘stories’ here doesn’t negate Mantel’s fictional abilities so much as prove her talent for working in the short form.

My other few favorites were the very short ones, about a fatal discovery of adultery, an appalling accident on a holiday in Greece, and a sighting of a dead father on a train. I also enjoyed “How Shall I Know You?” in which an author is invited to give a talk to a literary society. I especially liked the jokey pep talks to self involving references to other authors: “come now, what would Anita Brookner do?” and “for sure A.S. Byatt would have managed it better.” Other topics include children’s horror at disability, colleague secrets at a Harley Street clinic, and a sister’s struggle with anorexia. The title story offers an alternative history in which Thatcher is assassinated by the IRA upon leaving an eye hospital after surgery.

In her stories Mantel reminds me most of Tessa Hadley. It’s high time I read another Mantel novel; most likely that will be the third Thomas Cromwell book, due out next year.

My rating:

In the Driver’s Seat by Helen Simpson (2005)

I liked this even more than Simpson’s first book, Four Bare Legs in a Bed, which I reviewed last year. The themes include motherhood (starting, in a couple of cases, in one’s early 40s), death versus new beginnings, and how to be optimistic in a world in turmoil. There’s gentle humor and magic to these stories that tempers some of the sadness. I especially liked “The Door,” about a grieving woman looking to restore her sense of security after a home break-in, “The Green Room,” a Christmas Carol riff (one of two Christmas-themed stories here) in which a woman is shown how her negative thoughts and obsession with the past are damaging her, and “Constitutional,” set on a woman’s one-hour circular walk during her lunch break and documenting her thoughts about everything from pregnancy to a nonagenarian friend’s funeral. [The UK title of the collection is Constitutional.]

I liked this even more than Simpson’s first book, Four Bare Legs in a Bed, which I reviewed last year. The themes include motherhood (starting, in a couple of cases, in one’s early 40s), death versus new beginnings, and how to be optimistic in a world in turmoil. There’s gentle humor and magic to these stories that tempers some of the sadness. I especially liked “The Door,” about a grieving woman looking to restore her sense of security after a home break-in, “The Green Room,” a Christmas Carol riff (one of two Christmas-themed stories here) in which a woman is shown how her negative thoughts and obsession with the past are damaging her, and “Constitutional,” set on a woman’s one-hour circular walk during her lunch break and documenting her thoughts about everything from pregnancy to a nonagenarian friend’s funeral. [The UK title of the collection is Constitutional.]

In two stories, “Every Third Thought” and “If I’m Spared,” a brush with death causes a complete change of outlook – but will it last? “The Year’s Midnight” creates a brief connection between frazzled mums at the swimming pool in the run-up to the holidays. “Up at a Villa” and the title story capture risky moments that blend fear and elation. In “The Tree,” which is funny and cringeworthy all at the same time, a man decides to take revenge on the company that ripped off his forgetful old mother. Prize for the best title goes to “The Phlebotomist’s Love Life,” though it’s the least interesting story of the 11.

(Found in a Little Free Library at the supermarket near my parents’ old house.)

Some favorite lines:

“the inevitable difficulty involved in discovering ourselves to others; the clichés and blindness and inadvertent misrepresentations”

“Always a recipe for depression, Christmas, when complex adults demanded simple joy without effort, a miraculous feast of stingless memory.”

“You shouldn’t be too interested in the past. You yourself now are the embodiment of what you have lived. What’s done is done.”

My rating:

The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal (2019)

I had sky-high hopes for Stradal’s follow-up after Kitchens of the Great Midwest (it was on my Most Anticipated list for the second half of the year). Theoretically, a novel about three pie-baking, beer-making female members of a Minnesota family should have been terrific. Like Kitchens, this is female-centered, on a foodie theme, set in the Midwest and structured as linked short stories. Here the chapters are all titled after amounts of money; they skip around in time between the 1950s and the present day and between the perspectives of Edith Magnusson, her estranged younger sister Helen Blotz, and Edith’s granddaughter, Diana Winter.

Edith and Helen have a rivalry as old as the Bible, based around an inheritance that Helen stole to reopen her husband’s family brewery, instead of sharing it with Edith. Ever since, Edith has had to work minimum-wage jobs at nursing homes and fast food restaurants to make ends meet. When Diana comes to live with her as a teenager, she, too, works hard to contribute to the family, but then gets caught up in a dodgy money-making scheme. It’s in penance for this error that she starts working at a local brewery, but beer soon becomes as much of an obsession for Diana as it once was for her great-aunt Helen.

Edith and Helen have a rivalry as old as the Bible, based around an inheritance that Helen stole to reopen her husband’s family brewery, instead of sharing it with Edith. Ever since, Edith has had to work minimum-wage jobs at nursing homes and fast food restaurants to make ends meet. When Diana comes to live with her as a teenager, she, too, works hard to contribute to the family, but then gets caught up in a dodgy money-making scheme. It’s in penance for this error that she starts working at a local brewery, but beer soon becomes as much of an obsession for Diana as it once was for her great-aunt Helen.

I had a few problems with the book’s setup: Helen is portrayed as a villain, and never fully sheds that stereotypical designation; meanwhile, Edith is passive and boring, just a bit “wet” (in British slang). Edith and Diana suffer more losses than seems likely or fair, and there are too many coincidences involved in Diana’s transformation into a master brewer. I also found it far-fetched that a brewery would hire her as a 19-year-old and let her practice making many, many batches of lager, all while she’s still underage. None of the characters fully came alive for me, though Diana was the closest. The ending wasn’t as saccharine as I expected, but still left me indifferent. I did like reading about the process of beer-making and flavor development, though, even though I’m not a beer drinker.

My rating:

Short story DNFs this year (in chronological order):

Mr Wrong by Elizabeth Jane Howard – I read the two shortest stories, “Summer Picnic” and “The Proposition.” The former was pleasantly like Elizabeth Taylor or Tessa Hadley lite; I got zero out of the latter.

I Want to Show You More by Jamie Quatro – I read the first two stories. “Decomposition,” about a woman’s lover magically becoming a physical as well as emotional weight on her and her marriage, has an interesting structure as well as second-person narration, but I fear the collection as a whole will just be a one-note treatment of a woman’s obsession with her affair.

I Want to Show You More by Jamie Quatro – I read the first two stories. “Decomposition,” about a woman’s lover magically becoming a physical as well as emotional weight on her and her marriage, has an interesting structure as well as second-person narration, but I fear the collection as a whole will just be a one-note treatment of a woman’s obsession with her affair.

Multitudes: Eleven Stories by Lucy Caldwell – I read the first two stories. I enjoyed the short opener, “The Ally Ally O,” which describes a desultory ride in the car with mother and sisters with second-person narration and no speech marks. I should have given up on “Thirteen,” though, a tired story of a young teen missing her best friend.

The Country Ahead of Us, the Country Behind by David Guterson – I read “Angels in the Snow” (last Christmas) and “Wood Grouse on a High Promontory Overlooking Canada” (the other week). Both were fine but not particularly memorable; a glance at the rest suggests that they’ll all be about baseball and hunting. If I wanted to read about dudes hunting I’d turn to Ernest Hemingway or David Vann. Nevertheless, I’ll keep this around in case I want to try it again after reading Snow Falling on Cedars this winter.

Currently reading:

Ship Fever by Andrea Barrett – Elegant stories about history, science and human error. Barrett is similar to A.S. Byatt in her style and themes, which are familiar to me from my reading of Archangel. This won a National Book Award in 1996.

Ship Fever by Andrea Barrett – Elegant stories about history, science and human error. Barrett is similar to A.S. Byatt in her style and themes, which are familiar to me from my reading of Archangel. This won a National Book Award in 1996.- Descent of Man by T. Coraghessan Boyle – Even in this slim volume, there are SO MANY stories, and all so different from each other. Some I love; some are meh. I’m tempted to leave a few unread, though then I can’t count this towards my year total…

- Sum: Tales from the Afterlives by David Eagleman – A bibliotherapy prescription for reading aloud. My husband and I read a few stories to each other, but I’m going it alone for the rest. This is fairly inventive in the vein of Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams, yet I find it repetitive.

Future prospects:

See also Laura’s excellent post about her favorite individual short stories.