20 Books of Summer, 5: Crudo by Olivia Laing (2018)

Behind on the challenge, as ever, I picked up a novella. It vaguely fits with a food theme as crudo, “raw” in Italian, can refer to fish or meat platters (depicted on the original hardback cover). In this context, though, it connotes the raw material of a life: a messy matrix of choices and random happenings, rooted in a particular moment in time.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

This is set over four and a bit months of 2017 and steeped in the protagonist’s detached horror at political and environmental breakdown. She’s just turned 40 and, in between two trips to New York City, has a vacation in Tuscany, dabbles in writing and art criticism, and settles into married life in London even though she’s used to independence and nomadism.

For as hyper-real as the contents are, Laing is doing something experimental, even fantastical – blending biography with autofiction and cultural commentary by making her main character, apparently, Kathy Acker. Never mind that Acker died of breast cancer in 1997.

I knew nothing of Acker but – while this is clearly born of deep admiration, as well as familiarity with her every written word – that didn’t matter. Acker quotes and Trump tweets are inserted verbatim, with the sources given in a “Something Borrowed” section at the end.

Like Jenny Offill’s Weather, this is a wry and all too relatable take on current events and the average person’s hypocrisy and sense of helplessness, with the lack of speech marks and shortage of punctuation I’ve come to expect from ultramodern novels:

she might as well continue with her small and cultivated life, pick the dahlias, stake the ones that had fallen down, she’d always known whatever it was wasn’t going to last for long.

40, not a bad run in the history of human existence but she’d really rather it all kept going, water in the taps, whales in the oceans, fruits and duvets, the whole sumptuous parade

This is how it is then, walking backwards into disaster, braying all the way.

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

I’ve somehow read almost all of Laing’s oeuvre (barring her essays, Funny Weather) and have found books like The Trip to Echo Spring, The Lonely City and Everybody wide-ranging and insightful. Crudo feels as faithful to life as Rachel Cusk’s autofiction or Deborah Levy’s autobiography, but also like an attempt to make something altogether new out of the stuff of our unprecedented times. No doubt some of the intertextuality of this, her only fiction to date, was lost on me, but I enjoyed it much more than I expected to – it’s funny as well as eminently quotable – and that’s always a win. (Little Free Library)

Books of Summer, 2: The Story of My Father by Sue Miller

I followed up my third Sue Miller novel, The Lake Shore Limited, with her only work of nonfiction, a short memoir about her father’s decline with Alzheimer’s and eventual death. James Nichols was an ordained minister and church historian who had been a professor or dean at several of the USA’s most elite universities. The first sign that something was wrong was when, one morning in June 1986, she got a call from police in western Massachusetts who had found him wandering around disoriented and knocking at people’s doors at 3 a.m. On the road and in her house after she picked him up, he described vivid visual delusions. He still had the capacity to smile “ruefully” and reply, when Miller explained what had happened and how his experience differed from reality, “Doggone, I never thought I’d lose my mind.”

Until his death five years later, she was the primary person concerned with his wellbeing. She doesn’t say much about her siblings, but there’s a hint of bitterness that the burden fell to her. “Throughout my father’s disease, I struggled with myself to come up with the helpful response, the loving response, the ethical response,” she writes. “I wanted to give him as much of myself as I could. But I also wanted, of course, to have my own life. I wanted, for instance to be able to work productively.” She had only recently found success with fiction in her forties and published two novels before her father died; she dedicated the second to him, but too late for him to understand the honor. Her main comfort was that he never stopped being able to recognize her when she came to visit.

Although the book moves inexorably towards a death, Miller lightens it with many warm and admiring stories from her father’s past. Acknowledging that she’ll never be able to convey the whole of his personality, she still manages to give a clear sense of who he was, and the trajectory of his illness, all within 170 pages. The sudden death of her mother, a flamboyant lyric poet, at age 60 of a heart attack, is a counterbalance as well as a potential contributing factor to his slow fading as each ability was cruelly taken from him: living alone, reading, going outside for walks, sleeping unfettered.

Sutton Hill, the nursing home where he lived out his final years, did not have a dedicated dementia ward, and Miller regrets that he did not receive the specialist care he needed. “I think this is the hardest lesson about Alzheimer’s disease for a caregiver: you can never do enough to make a difference in the course of the disease. Hard because what we feel anyway is that we have never done enough. We blame ourselves. We always find ourselves deficient in devotion.” She conceived of this book as a way of giving her father back his dignity and making a coherent story out of what, while she was living through it, felt like a chaotic disaster. “I would snatch him back from the meaninglessness of Alzheimer’s disease.”

And in the midst of it all, there were still humorous moments. Her poor father fell in love with his private nurse, Marlene, and believed he was married to her. Awful as it was, there was also comedy in an extended family story Miller tells, one I think I’m unlikely to forget: They had always vacationed in New Hampshire rental homes, and when her father learned one of the opulent ‘cottages’ was coming up for sale, he agreed to buy it sight unseen. The seller was a hoarder … of cats. Eighty of them. He had given up cleaning up after them long ago. When they went to view the house her father had already dropped $30,000 on, it was a horror. Every floor was covered inches deep in calcified feces. It took her family an entire summer to clean the place and make it even minimally habitable. Only afterwards could she appreciate the incident as an early sign of her father’s impaired decision making.

I’ve read a fair few dementia-themed memoirs now. As people live longer, this suite of conditions is only going to become more common; if it hasn’t affected one of your own loved ones, you likely have a friend or neighbor who has had it in their family. This reminded me of other clear-eyed, compassionate yet wry accounts I’ve read by daughter-caregivers Elizabeth Hay (All Things Consoled) and Maya Shanbhag Lang (What We Carry). It was just right as a pre-Father’s Day read, and a novelty for fans of Miller’s novels. (Charity shop)

20 Books of Summer, 1: Small Fires by Rebecca May Johnson

So far I’m sticking to my vague plan and reading foodie lit, like it’s 2020 all over again. At the same time, I’m tackling a few books that I received as review copies last year but that have been on my set-aside pile for longer than I’d like to admit. Later in the summer I’ll branch out from the food theme, but always focusing on books I own and have been meaning to read.

Without further ado, my first of 20 Books of Summer:

Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen by Rebecca May Johnson (2022)

“I tried to write about cooking, but I wrote a hot red epic.”

Johnson’s debut is a hybrid work, as much a feminist essay collection as it is a memoir about the role that cooking has played in her life. She chooses to interpret apron strings erotically, such that the preparation of meals is not gendered drudgery or oppression but an act of self-care and love for others.

“The kitchen is a space for theorizing!”

While completing a PhD on the reception of The Odyssey and its translation history, Johnson began to think about dishes as translations, or even performances, of a recipe. In two central chapters, “Hot Red Epic” and “Tracing the Sauce Text,” she reckons that she has cooked the same fresh Italian tomato sauce, with nearly infinite small variations, a thousand times over ten years. Where she lived, what she looked like, who she cooked for: so many external details changed, but this most improvisational of dishes stayed the same.

Just a peek at the authors cited in her bibliography – not just the expected subjects like MFK Fisher and Nigella Lawson but also Goethe, Lorde, Plath, Stein, Weil, Winnicott – gives you an idea of how wide-ranging and academically oriented the book is, delving into the psychology of cooking and eating. Oh yes, there will be Freudian sausages. There are also her own recipes, of a sort: one is a personal prose piece (“Bad News Potatoes”) and another is in poetic notation, beginning “I made Mrs Beeton’s / recipe for frying sausages”.

“The recipe is an epic without a hero.”

I particularly enjoyed the essay “Again and Again, There Is That You,” in which Johnson determinedly if chaotically cooks a three-course meal for someone who might be a lover. The mixture of genres and styles is inventive, but a bit strange; my taste would call for more autobiographical material and less theory. The most similar work I’ve read is Recipe by Lynn Z. Bloom, which likewise pulled in some seemingly off-topic strands. I’d be likely to recommend Small Fires to readers of Supper Club.

With thanks to Pushkin Press for the free copy for review.

20 Books of Summer 2023 Plan

It’s my sixth year participating in Cathy’s 20 Books of Summer challenge, which starts today and runs through the 1st of September. In previous years I’ve chosen a theme.

2018: Books by women

2019: Fauna

2020: Food

2021: Colours

2022: Flora

Only in 2018, I think, was I strict enough with myself to only read books that I own, but every year that’s been my main goal: to clear things from the print TBR.

So, that means: no library books, no review copies bar the long-neglected backlog or the set-aside ones, and Kindle books only if I purchased them. Though I won’t be prescriptive about it, I’d like to prioritize hardbacks, recent acquisitions or longtime shelf-sitters, and books by women.

I thought about having no theme, or multiple mini ones, this year. However, I’ve amassed so many foodie reads that I could easily fill my 20 just with that topic (fiction and nonfiction pictured below, with some supplementary summery reads at left), so I’ll see how I go.

Below is my set-aside and review backlog area, which takes up much of the top two shelves. The bottom shelf is books I’m keen to reread. I could easily select some of my 20 from here.

I hoped to get ahead by reading one or two relevant books on the plane back from America, where I’ve been for the last 10 days for my sister’s nursing school graduation and some sadmin for my mom. Did I manage it? After I get over the jet lag, I’ll report back with my first read or two.

Are you joining in the summer reading challenge? What’s the first book on the docket?

20 Books of Summer, 17–20: Bennett, Davidson, Diffenbaugh, Kimmerer

As per usual, I’m squeezing in my final 20 Books of Summer reviews late on the very last day of the challenge. I’ll call it a throwback to the all-star procrastination of my high school and college years. This was a strong quartet to finish on: two novels, the one about (felling) trees and the other about communicating via flowers; and two nonfiction books about identifying trees and finding harmony with nature.

Tree-Spotting: A Simple Guide to Britain’s Trees by Ros Bennett; illus. Nell Bennett (2022)

Botanist Ros Bennett has designed this as a user-friendly guide that can be taken into the field to identify 52 of Britain’s most common trees. Most of these are native species, plus a few naturalized ones. “Walks in the countryside … take on a new dimension when you find yourself on familiar, first-name terms with the trees around you,” she encourages. She introduces tree families, basics of plant anatomy and chemistry, and the history of the country’s forests before moving into identification. Summer leaves make ID relatively easy with a three-step set of keys, explained in words as well as with impressively detailed black-and-white illustrations of representative species’ leaves (by her daughter, Nell Bennett).

Seasonality makes things trickier: “Identifying plants is not rocket science, though occasionally it does require lots of patience and a good hand lens. Identifying trees in winter is one of those occasions.” This involves a close look at details of the twigs and buds – a challenge I’ll be excited to take up on canalside walks later this year. The third section of the book gives individual profiles of each featured species, with additional drawings. I learned things I never realized I didn’t know (like how to pronounce family names, e.g., Rosaceae is “Rose-A-C”), and formalized other knowledge. For instance, I can recognize an ash tree by sight, but now I know you identify an ash by its 9–13 compound, opposite, serrated leaflets.

Some of the information was more academic than I needed (as with one of my earlier summer reads, The Ash Tree by Oliver Rackham), but it’s easy to skip any sections that don’t feel vital and come back to them another time. I most valued the approachable keys and their accompanying text, and will enjoy taking this compact naked hardback on autumn excursions. Bennett never dumbs anything down, and invites readers to delight in discovery. “So – go out, introduce yourself to your neighbouring trees and wonder at their beauty, ingenuity and variety.”

With thanks to publicist Claire Morrison and Welbeck for the free copy for review.

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson (2021)

When this would-be Great American Novel* arrived unsolicited through my letterbox last summer, I was surprised I’d not encountered the pre-publication buzz. The cover blurb is from Nickolas Butler, which gives you a pretty good sense of what you’re getting into: a gritty, working-class story set in what threatens to be an overwhelmingly male milieu. For generations, Rich Gundersen’s family has been involved in logging California’s redwoods. Davidson is from Arcata, California, and clearly did a lot of research to recreate an insider perspective and a late 1970s setting. There is some specialist vocabulary and slang (the loggers call the largest trees “big pumpkins”), but it’s easy enough to understand in context.

What saves the novel from going too niche is the double billing of Rich and his wife, Colleen, who is an informal community midwife and has been trying to get pregnant again almost ever since their son Chub’s birth. She’s had multiple miscarriages, and their family and acquaintances have experienced alarming rates of infant loss and severe birth defects. Conservationists, including an old high school friend of Colleen’s, are attempting to stop the felling of redwoods and the spraying of toxic herbicides.

What saves the novel from going too niche is the double billing of Rich and his wife, Colleen, who is an informal community midwife and has been trying to get pregnant again almost ever since their son Chub’s birth. She’s had multiple miscarriages, and their family and acquaintances have experienced alarming rates of infant loss and severe birth defects. Conservationists, including an old high school friend of Colleen’s, are attempting to stop the felling of redwoods and the spraying of toxic herbicides.

A major element, then, is people gradually waking up to the damage chemicals are doing to their waterways and, thereby, their bodies. The problem, for me, was that I realized this much earlier than any of the characters, and it felt like Davidson laid it on too thick with the many examples of human and animal deaths and deformities. This made the book feel longer and less subtle than, e.g., The Overstory. I started it as a buddy read with Marcie (Buried in Print) 11 months ago and quickly bailed, trying several more times to get back into the book before finally resorting to skimming to the end. Still, especially for a debut author, Davidson’s writing chops are impressive; I’ll look out for what she does next.

*I just spotted that it’s been shortlisted for the $25,000 Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award.

With thanks to Tinder Press for the proof copy for review.

The Language of Flowers by Vanessa Diffenbaugh (2011)

The cycle would continue. Promises and failures, mothers and daughters, indefinitely.

The various covers make this look more like chick lit than it is. Basically, it’s solidly readable issues- and character-driven literary fiction, on the lighter side but of the caliber of any Oprah’s Book Club selection. It reminded me most of White Oleander by Janet Fitch, one of my 20 Books selections in 2018, because of the focus on the foster care system and a rebellious girl’s development in California, and the floral metaphors.

The various covers make this look more like chick lit than it is. Basically, it’s solidly readable issues- and character-driven literary fiction, on the lighter side but of the caliber of any Oprah’s Book Club selection. It reminded me most of White Oleander by Janet Fitch, one of my 20 Books selections in 2018, because of the focus on the foster care system and a rebellious girl’s development in California, and the floral metaphors.

In Diffenbaugh’s debut, Victoria Jones ages out of foster care at 18 and leaves her group home for an uncertain future. She spends time homeless in San Francisco but her love of flowers, and particularly the Victorian meanings assigned to them, lands her work in a florist’s shop and reconnects her with figures from her past. Chapters alternate between her present day and the time she came closest to being adopted – by Elizabeth, who owned a vineyard and loved flowers, when she was nine. We see how estrangements and worries over adequate mothering recur, with Victoria almost a proto-‘Disaster Woman’ who keeps sabotaging herself. Throughout, flowers broker reconciliations.

I won’t say more about a plot that would be easy to spoil, but this was a delight and reminded me of a mini flower dictionary with a lilac cover and elaborate cursive script that I owned when I was a child. I loved the thought that flowers might have secret messages, as they do for the characters here. Whatever happened to that book?! (Charity shop)

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2013)

I’d heard Kimmerer recommended by just about every nature writer around, North American or British, and knew I needed this on my shelf. Before I ever managed to read it, I saw her interviewed over Zoom by Lucy Jones in July 2021 about her other popular science book, Gathering Moss, which was first published 18 years ago but only made it to the UK last year. So I knew what a kind and peaceful person she is: she just emanates warmth and wisdom, even over a computer screen.

And I did love Braiding Sweetgrass nearly as much as I expected to, with the caveat that the tiny-print 400 pages of my paperback edition make the essays feel very dense. I could only read a handful of pages in a sitting. Also, after about halfway, it started to feel a bit much, like maybe she had given enough examples from her life, Native American legend and botany. The same points about gratitude for the gifts of the Earth, kinship with other creatures, responsibility and reciprocity are made over and over.

However, I feel like this is the spirituality the planet needs now, so I’ll excuse any repetition (and the basket-weaving essay I thought would never end). “In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” (She’s funny, too, so you don’t have to worry about the contents getting worthy.) She effectively wields the myth of the Windigo as a metaphor for human greed, essential to a capitalist economy based on “emptiness” and “unmet desires.”

However, I feel like this is the spirituality the planet needs now, so I’ll excuse any repetition (and the basket-weaving essay I thought would never end). “In a world of scarcity, interconnection and mutual aid become critical for survival. So say the lichens.” (She’s funny, too, so you don’t have to worry about the contents getting worthy.) She effectively wields the myth of the Windigo as a metaphor for human greed, essential to a capitalist economy based on “emptiness” and “unmet desires.”

I most enjoyed the shorter essays that draw on her fieldwork or her experience of motherhood. “The Gift of Strawberries” – “An Offering” – “Asters and Goldenrod” make a stellar three-in-a-row, and “Collateral Damage” is an excellent later one about rescuing salamanders from the road, i.e. doing the small thing that we can do rather than being overwhelmed by the big picture of nature in crisis. “The Sound of Silverbells” is one of the most well-crafted individual pieces, about taking a group of students camping when she lived in the South. At first their religiosity (creationism and so on) grated, but when she heard them sing “Amazing Grace” she knew that they sensed the holiness of the Great Smoky Mountains.

But the pair I’d recommend most highly, the essays that made me weep, are “A Mother’s Work,” about her time restoring an algae-choked pond at her home in upstate New York, and its follow-up, “The Consolation of Water Lilies,” about finding herself with an empty nest. Her loving attention to the time-consuming task of bringing the pond back to life is in parallel to the challenges of single parenting, with a vision of the passing of time being something good rather than something to resist.

Here are just a few of the many profound lines:

For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.

I’m a plant scientist and I want to be clear, but I am also a poet and the world speaks to me in metaphor.

Ponds grow old, and though I will too, I like the ecological idea of aging as progressive enrichment, rather than progressive loss.

This will be a book to return to time and again. (Gift from my wish list several years ago)

I also had one DNF from this summer’s list:

Human Croquet by Kate Atkinson: This reminded me of a cross between The Crow Road by Iain Banks and The Heavens by Sandra Newman, what with the teenage narrator and a vague time travel plot with some Shakespearean references. I put it on the pile for this challenge because I’d read it had a forest setting. I haven’t had much luck with Atkinson in the past and this didn’t keep me reading past page 60. (Little Free Library)

A Look Back at My 20 Books of Summer 2022

Half of my reads are pictured here. The rest were e-books (represented by the Kindle) or have already had to go back to the library.

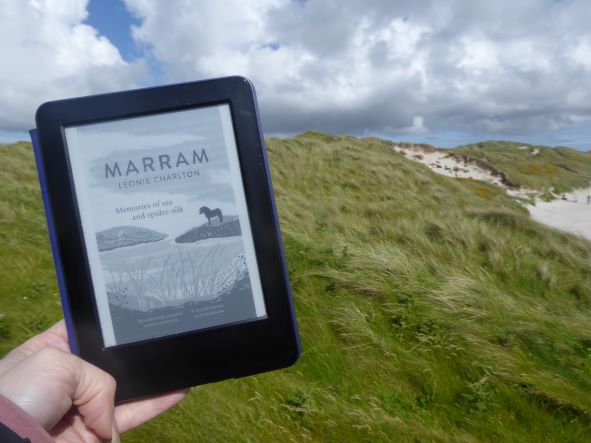

My fiction standout was The Language of Flowers, reviewed above. Nonfiction highlights included Forget Me Not and Braiding Sweetgrass, with Tree-Spotting the single most useful book overall. I also enjoyed reading a couple of my selections on location in the Outer Hebrides. The hands-down loser (my only 1-star rating of the year so far, I think?) was Bonsai. As always, there are many books I could have included and wished I’d found the time for, like (on my Kindle) A House among the Trees by Julia Glass, This Is Your Mind on Plants by Michael Pollan and Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard.

At the start, I was really excited about my flora theme and had lots of tempting options lined up, some of them literally about trees/flowers and others more tangentially related. As the summer went on, though, I wasn’t seeing enough progress so scrambled to substitute in other things I was reading from the library or for paid reviews. This isn’t a problem, per se, but my aim with this challenge has generally been to clear TBR reads from my own shelves. Maybe I didn’t come up with enough short and light options (just two novella-length works and a poetry collection; only the Diffenbaugh was what I’d call a page-turner); also, even with the variety I’d built in, having a few plant quest memoirs got a bit samey.

Next year…

I’m going to skip having a theme and set myself just one simple rule: any 20 print books from my shelves (NOT review copies). There will then be plenty of freedom to choose and substitute as I go along.

Summery Reads from Holly Hopkins, Sarah McCoy, Phil Stamper and Edith Wharton

Every season, I try to choose a few books that feel appropriate for their settings or titles. A few of these I’ve already mentioned briefly, as part of my heat wave reading suggestions. Much as I love autumn, the end of summer tends to coincide with gloomy musings for me. However, it’s farewell to August with four reasonably cheerful books: a poetry collection about England then and now, city and country; an escapist novel set on the Caribbean island of Mustique in the 1970s; the story of four gay friends going their separate ways for a high school summer of adventure; and a less-tragic-than-expected American classic.

The English Summer by Holly Hopkins (2022)

Colour, geology and history are major sources of imagery in this debut full-length collection. Churches and cemeteries, museums and manor houses, versus hospitals and rental flats: this is the stuff of a country that has swapped its illustrious past for the dismal reality of the everyday. The collection closes with “England, Where Did You Go?” which ends, “should I get out in search of you, … / I’d be left wandering down dual carriageways, / looking across bean fields and filthy ditches.” Hopkins imagines a government that decides to address climate change by assigning weekly community service hours – nearly twice as many for women, who always bear the greater burden for domestic work.

Colour, geology and history are major sources of imagery in this debut full-length collection. Churches and cemeteries, museums and manor houses, versus hospitals and rental flats: this is the stuff of a country that has swapped its illustrious past for the dismal reality of the everyday. The collection closes with “England, Where Did You Go?” which ends, “should I get out in search of you, … / I’d be left wandering down dual carriageways, / looking across bean fields and filthy ditches.” Hopkins imagines a government that decides to address climate change by assigning weekly community service hours – nearly twice as many for women, who always bear the greater burden for domestic work.

It’s mostly alliteration, repetition, and internal or slant rhymes here. I particularly liked the pair “Rows of Differently Coloured Houses,” which contrasts bright seaside facades with the “Lakes of postwar pebbledash / grey on grey on grey on grey” seen from a Megabus, and “Stratigraphy,” about the archaeologist’s work. Not many standouts otherwise, but it was still worth a try. (New purchase – the publisher, Penned in the Margins, lured me with a sale)

Mustique Island by Sarah McCoy (2022)

Mustique is a private island in the St. Vincent archipelago that became a playground of the rich and famous in the 1970s, with Princess Margaret and Mick Jagger regular visitors. In McCoy’s novel – inspired by real events and people, and featuring cameos from the aforementioned celebrities as well as the island’s owners at the time, the baron Colin Tennant and his wife, Lady Anne Glenconner (who, I was amused to spot at the library the other day, has written her own fictional tribute to the island, Murder on Mustique) – Willy May, a Texan with a small fortune at her disposal thanks to her divorce from an English brewing magnate, sails in on a private boat and decides to build her own villa on Mustique. She’s uncomfortable with the way locals, who only have service jobs, are sometimes paraded out for colonial displays of pomp. Her two young adult daughters, Hilly and Joanne, later join her. The one has been a model in Paris, where she became addicted to amphetamines.

Mustique is a private island in the St. Vincent archipelago that became a playground of the rich and famous in the 1970s, with Princess Margaret and Mick Jagger regular visitors. In McCoy’s novel – inspired by real events and people, and featuring cameos from the aforementioned celebrities as well as the island’s owners at the time, the baron Colin Tennant and his wife, Lady Anne Glenconner (who, I was amused to spot at the library the other day, has written her own fictional tribute to the island, Murder on Mustique) – Willy May, a Texan with a small fortune at her disposal thanks to her divorce from an English brewing magnate, sails in on a private boat and decides to build her own villa on Mustique. She’s uncomfortable with the way locals, who only have service jobs, are sometimes paraded out for colonial displays of pomp. Her two young adult daughters, Hilly and Joanne, later join her. The one has been a model in Paris, where she became addicted to amphetamines.

Love is on the cards for all three main female characters, but there’s heartache along the way as well. Closer to women’s fiction than I generally choose, this was a frothy indulgence that was fun to read but could be shorter and needn’t have tried so hard to make serious points about motherhood and to evoke the time period, e.g., with a list of what’s on the radio. I have also reviewed McCoy’s Marilla of Green Gables. (Offered by publicist via NetGalley)

Golden Boys by Phil Stamper (2022)

Four gay high schoolers in small-town Ohio look forward to a summer of separate travels for jobs and internships and hope their friendships will stay the course. We have Gabriel, a nature lover off to volunteer for a Boston save-the-trees non-profit; Sal, his friend with benefits, who dreams of bypassing college for a career in politics so interns at his local senator’s office in Washington, DC; Reese, headed to Paris for a fashion design course; and Heath, escaping his parents’ divorce and moving chaos to stay with an aunt and cousin in Florida and work at their beach café. With alternating first-person passages from all four characters, plus transcriptions of their conversation threads, this moves quickly.

Four gay high schoolers in small-town Ohio look forward to a summer of separate travels for jobs and internships and hope their friendships will stay the course. We have Gabriel, a nature lover off to volunteer for a Boston save-the-trees non-profit; Sal, his friend with benefits, who dreams of bypassing college for a career in politics so interns at his local senator’s office in Washington, DC; Reese, headed to Paris for a fashion design course; and Heath, escaping his parents’ divorce and moving chaos to stay with an aunt and cousin in Florida and work at their beach café. With alternating first-person passages from all four characters, plus transcriptions of their conversation threads, this moves quickly.

Reese has been secretly infatuated with Heath for ages, but three of the four will consider new dating opportunities this summer (the fourth just becomes a workaholic). Secondary characters are pansexual and nonbinary – it’s a whole new world from when I was in high school! Initially, I found the inner monologues too one-note, but I think Stamper’s aim was to recreate the teenage struggle for self-confidence and individuality and has captured that life stage’s inherent anxiety. I also would have trimmed the preparatory stuff; nearly 100 pages before the first of them leaves Ohio is a bit much. This YA novel was a sweet, fun page turner and the perfect replacement to the Heartstopper series as my summer crush. However, I don’t think I was taken enough with the characters to read next year’s projected sequel. (Public library)

Summer by Edith Wharton (1917)

Charity Royall was born into poverty but brought down the mountain and adopted by a kindly couple into respectable North Dormer society. Mrs. Royall has died before the action starts, but as a young woman Charity still lives with Lawyer Royall, her guardian, and works at the library. When a stranger, Mr. Harney, arrives in their New England town to survey the local architecture, it’s clear right away that he’ll be a romantic prospect for her. “She had always thought of love as something confused and furtive, and he made it as bright and open as the summer air.” However, shame over her lowly origins – she is so snobbish every time she comes into contact with someone from the mountain – continues to plague her.

Charity Royall was born into poverty but brought down the mountain and adopted by a kindly couple into respectable North Dormer society. Mrs. Royall has died before the action starts, but as a young woman Charity still lives with Lawyer Royall, her guardian, and works at the library. When a stranger, Mr. Harney, arrives in their New England town to survey the local architecture, it’s clear right away that he’ll be a romantic prospect for her. “She had always thought of love as something confused and furtive, and he made it as bright and open as the summer air.” However, shame over her lowly origins – she is so snobbish every time she comes into contact with someone from the mountain – continues to plague her.

Although Harney returns her affections and they set up a little love nest in an abandoned house in the woods, uncertainty lingers as to whether he’ll consider marriage to Charity beneath him. This skirts Tess of the d’Urbervilles territory but doesn’t turn nearly as tragic as Ethan Frome (apparently, Wharton called this a favourite among her works, and referred to it as “the Hot Ethan”). Charity isn’t as vain as another Hardy heroine, Bathsheba Everdene; she’s an endearing blend of innocent and worldly, and her realistic reaction to what fate seems to decree feels like about the best one can expect for her time. Melodrama aside, I truly enjoyed the descriptions of a quintessential American summer with picnics and Fourth of July fireworks. Ethan fan or not, you should definitely read this one. (University library)

Bookish Bits and Bobs

It’s felt like a BIG week for prize news. First we had the Booker Prize longlist, about which I’ve already shared some thoughts. My next selection from it is Trust by Hernan Diaz, which I started reading last night. The shortlist comes out on 6 September. We have our book club shadowing application nearly ready to send off – have your fingers crossed for us!

Then on Friday the three Wainwright Prize shortlists (I gave my reaction to the longlists last month) were announced: one for nature writing, one for conservation writing, and – new this year – one for children’s books on either.

I’m delighted that my top two overall picks, On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Silent Earth by Dave Goulson, are still in the running. I’ve read half of the nature list and still intend to read Shadowlands, which is awaiting me at the library. I’d happily read any of the remaining books on the conservation list and have requested the few that my library system owns. Of the children’s nominees, I’m currently a third of the way through Julia and the Shark and also have the Davies out from the library to read.

I’m delighted that my top two overall picks, On Gallows Down by Nicola Chester and Silent Earth by Dave Goulson, are still in the running. I’ve read half of the nature list and still intend to read Shadowlands, which is awaiting me at the library. I’d happily read any of the remaining books on the conservation list and have requested the few that my library system owns. Of the children’s nominees, I’m currently a third of the way through Julia and the Shark and also have the Davies out from the library to read.

As if to make up for the recent demise of the Costa Awards, the Folio Prize has decided to split into three categories: fiction, nonfiction and poetry; the three finalists will then go head-to-head to compete for the overall prize. I’ve always wondered how the Folio judges pit such different books against each other. This makes theirs an easier job, I guess?

Speaking of prize judging, I’ve been asked to return as a manuscript judge for the 2023 McKitterick Prize administered by the Society of Authors, the UK trade union for writers. (Since 1990, the McKitterick Prize has been awarded to a debut novelist aged 40+. It’s unique in that it considers unpublished manuscripts as well as published novels – Political Quarterly editor Tom McKitterick, who endowed the Prize, had an unpublished novel at the time of his death.) Although I’d prefer to be assessing ‘real’ books, the fee is welcome. Submissions close in October, and I’ll spend much of November–December on the reading.

Somehow, it’s August. Which means:

- Less than a month left for the remaining 10 of my 20 Books of Summer. I’m actually partway through another 12 books that would be relevant to my flora theme, so I just have to make myself finish and review 10 of them.

- It’s Women in Translation month! I’m currently reading The Last Wild Horses by Maja Lunde and have The Summer Book by Tove Jansson out from the library. I also have review copies of two short novels from Héloïse Press, and have placed a library hold on The Disaster Tourist by Yun Ko-eun. We’ll see how many of these I get to.

Marcie (Buried in Print) and I have embarked on a buddy read of Cloudstreet by Tim Winton. I’ve never read any of his major works and I’m enjoying this so far.

Marcie (Buried in Print) and I have embarked on a buddy read of Cloudstreet by Tim Winton. I’ve never read any of his major works and I’m enjoying this so far.

Goodreads, ever so helpfully, tells me I’m currently 37 books behind schedule on my year’s reading challenge. What the website doesn’t know is that, across my shelves and e-readers, I am partway through – literally – about 90 books. So if I could just get my act together to sit down and finish things instead of constantly grabbing for something new, my numbers would look a lot better. Nonetheless, I’ve read loads by anyone’s standard, and will read lots more before the end of the year, so I’m not going to sweat it about the statistics.

A new home has meant fun tasks like unpacking my library (as well as not-so-fun ones like DIY). As a reward for successfully hosting a housewarming party and our first weekend guests, I let myself unbox and organize most of the rest of the books in my new study. My in-laws are bringing us a spare bookcase soon; it’s destined to hold biographies, poetry and short story collections. I thought I’d be able to house all the rest of my life writing and literary reference books on two Billy bookcases, but it’s required some clever horizontal stacks, special ‘displays’ on the top of each case, and, alas, some double-stacking – which I swore I wouldn’t do.

Scotland and Victoriana displays, unread memoirs and literary reference books at left; medical reads display and read memoirs at right.

I need to acquire one more bookcase, a bit narrower than a Billy, to hold the rest of my read fiction plus some overflow travel and humour on the landing.

I get a bit neurotic about how my library is organized, so questions that others wouldn’t give much thought to plague me:

- Should I divide read from unread books?

- Do I hide the less sightly proof copies in a stack behind the rest?

- Is it better to have hardbacks and paperbacks all in one sequence, or separate them to maximize space?

(I’ve employed all of these options for various categories.)

I also have some feature shelves to match particular challenges, like novellas, future seasonal reads, upcoming releases and review books to catch up on, as well as signed copies and recent acquisitions to prioritize. Inevitably, once I’ve arranged everything, I find one or two strays that then don’t fit on the shelves I’ve allotted. Argh! #BibliophileProblems, eh?

I’ve been skimming through The Bookman’s Tale by Ronald Blythe, and this passage from the diary entry “The Bookshelf Cull” stood out to me:

“Should you carry a dozen volumes from one shelf to another, you will most likely be carrying hundreds before you finish. Sequences will be thrown out; titles will have to be regrouped; subjects will demand respect.”

What are your August reading plans? Following any literary prizes?

How are your shelves looking? Are they as regimented as mine, or more random?

Hilary: Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (I’d second that one; here’s

Hilary: Briefly, A Delicious Life by Nell Stevens (I’d second that one; here’s

This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

This comes out from Abrams Press in the USA on 8 November and I’ll be reviewing it for Shelf Awareness, so I’ll just give a few brief thoughts for now. Barba is a poet and senior editor for New York Review Books. She has collected pieces from a wide range of American literature, including essays, letters and early travel writings as well as poetry, which dominates.

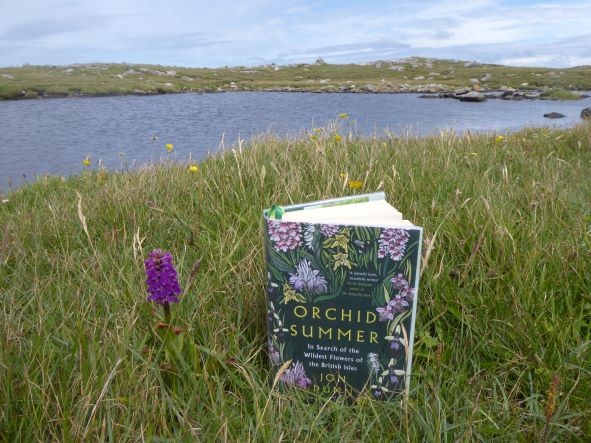

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:

A good case of nominative determinism – the author’s name is pronounced “leaf” – and fun connections abound: during the course of his year-long odyssey, he spends time plant-hunting with Jon Dunn and Sophie Pavelle, whose books featured earlier in my flora-themed summer reading:  I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the

I was fascinated by the concept behind this one. “In the spring of 1936 a writer planted roses” is Solnit’s refrain; from there sprawls a book that’s somehow about everything: botany, geology, history, politics and war – as well as, of course, George Orwell’s life and works (with significant overlap with the

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.

These college students’ bond is primarily physical, with an overlay of intellectual pretentiousness: they read to each other from the likes of Proust before they go to bed. Zambra, a Chilean poet and fiction writer, zooms in and out to spotlight each one’s other connections with friends and lovers and presage how the past will lead to separate futures. Already we see Julio thinking about how this time-limited relationship will be remembered in memory and in writing. The plot of a story Zambra references in this allusion-heavy work, “Tantalia” by Macedonio Fernández, provides the title: a couple buy a small plant to signify their love, but realize that maybe wasn’t a great idea given that plants can die.