Guest Review of Greene Ferne Farm by Richard Jefferies (#NovNov25)

As busy as he is as a lecturer in animal ecology at the University of Reading (and a multi-instrumentalist in several folk/Americana bands), my husband, Dr Chris Foster, managed to find time to read and review (below) something for Novellas in November. This is a random, obscure Victorian novel (from 1880) that we picked up at a book sale in Kingsclere last month.

“The 19th-century author Richard Jefferies is better remembered as a nature writer than as a novelist, and in this slight early novella (albeit published only seven years before his death from tuberculosis at age 38) it is indeed his evocation of the landscapes, wildlife and weather of rural Wiltshire that stand out most.

“Jefferies conjures atmosphere skilfully, from an uneasy night lost on chalk downland in thick fog to the lonely, dust-filled room where an avaricious old farmer looks out at the sunset from his armchair. There’s a sense of abundant nature as a backdrop for rural life that can be taken for granted, a sense of connectivity across generations – “the cuckoo came and went; the swallows sailed for the golden sands of the south; the leaves, brown and orange and crimson, dropped and died” – but also a prescient fear expressed here by a landowning squire that modern farming methods such as ‘ploughing engines’ might “suck every atom out of the soil.” The abundance of corncrakes portrayed around Greene Ferne is just one reminder for contemporary readers of how much wildlife has been lost from farmland since Jefferies was writing.

“Jefferies conjures atmosphere skilfully, from an uneasy night lost on chalk downland in thick fog to the lonely, dust-filled room where an avaricious old farmer looks out at the sunset from his armchair. There’s a sense of abundant nature as a backdrop for rural life that can be taken for granted, a sense of connectivity across generations – “the cuckoo came and went; the swallows sailed for the golden sands of the south; the leaves, brown and orange and crimson, dropped and died” – but also a prescient fear expressed here by a landowning squire that modern farming methods such as ‘ploughing engines’ might “suck every atom out of the soil.” The abundance of corncrakes portrayed around Greene Ferne is just one reminder for contemporary readers of how much wildlife has been lost from farmland since Jefferies was writing.

“The plot is lacklustre in comparison to the prose: a Hardyesque blend of love triangles and scenes from rural life, with no sense that the occasionally dramatic events portrayed are helping to build any narrative momentum. The portrayals of rustic village folk, complete with thick country accents, feel clichéd and idealised, especially given the decidedly un-Hardyesque happy ending, but the quality of Jefferies’ writing for much of Greene Ferne Farm is at least an encouragement to check out his other, better-known work.” [126 pages] ![]()

Review Catch-Up: Medical Nonfiction & Nature Poetry

Catching up on four review copies I was sent earlier in the year and have finally got around to finishing and writing about. I have two works of health-themed nonfiction, one a narrative about organ transplantation and the other a psychiatrist’s memoir; and two books of nature poetry, a centuries-spanning anthology and a recent single-author collection.

The Story of a Heart by Rachel Clarke

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Rachel Clarke is a palliative care doctor and voice of wisdom on end-of-life issues. I was a huge fan of her Dear Life and admire her public critique of government policies that harm the NHS. (I’ve also reviewed Breathtaking, her account of hospital working during Covid-19.) While her three previous books all incorporate a degree of memoir, this is something different: narrative nonfiction based on a true story from 2017 and filled in with background research and interviews with the figures involved. Clarke has no personal connection to the case but, like many, discovered it via national newspaper coverage. Nine-year-old Max Johnson spent nearly a year in hospital with heart failure after a mysterious infection. Keira Ball, also nine, was left brain-dead when her family was in a car accident on a dangerous North Devon road. Keira’s heart gave Max a second chance at life.

Clarke zooms in on pivotal moments: the accident, the logistics of getting an organ from one end of the country to another, and the separate recovery and transplant surgeries. She does a reasonable job of recreating gripping scenes despite a foregone conclusion. Because I’ve read a lot around transplantation and heart surgery (such as When Death Becomes Life by Joshua D. Mezrich and Heart by Sandeep Jauhar), I grew impatient with the contextual asides. I also found that the family members and medical professionals interviewed didn’t speak well enough to warrant long quotation. All in all, this felt like the stuff of a long-read magazine article rather than a full book. The focus on children also results in mawkishness. However, the Baillie Gifford Prize judges who shortlisted this clearly disagreed. I laud Clarke for drawing attention to organ donation, a cause dear to my family. This case was instrumental in changing UK law: one must now opt out of donating organs instead of registering to do so.

With thanks to Abacus Books (Little, Brown) for the proof copy for review.

You Don’t Have to Be Mad to Work Here: A Psychiatrist’s Life by Dr Benji Waterhouse

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Waterhouse is also a stand-up comedian and is definitely channelling Adam Kay in his funny and touching debut memoir. Most chapters are pen portraits of patients and colleagues he has worked with. He also puts his own family under the microscope as he undergoes therapy to work through the sources of his anxiety and depression and tackles his reluctance to date seriously. In the first few years, he worked in a hospital and in community psychiatry, which involved house visits. Even though identifying details have been changed to make the case studies anonymous, Waterhouse manages to create memorable characters, such as Tariq, an unhoused man who travels with a dog (a pity Waterhouse is mortally afraid of dogs), and Sebastian, an outwardly successful City worker who had been minutes away from hanging himself before Waterhouse and his colleague rang on the door.

Along with such close shaves, there are tragic mistakes and tentative successes. But progress is difficult to measure. “Predicting human behaviour isn’t an exact science. We’re just relying on clinical assessment, a gut feeling and sometimes a prayer,” Waterhouse tells his medical student. The book gives a keen sense of the challenges of working for the NHS in an underfunded field, especially under Covid strictures. He is honest and open about his own failings but ends on the positive note of making advances in his relationship with his parents. This was a great read that I’d recommend beyond medical-memoir junkies like myself. Waterhouse has storytelling chops and the frequent one-liners lighten even difficult topics:

The sum total of my wisdom from time spent in the community: lots of people have complicated, shit lives.

Ambiguous statements … need clarification. Like when a depressed patient telephones to say they’re ‘in a bad place’. I need to check if they’re suicidal or just visiting Peterborough.

What is it about losing your mind that means you so often mislay your footwear too?

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Green Verse: An Anthology of Poems for Our Planet, ed. Rosie Storey Hilton

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

Part of the “In the Moment” series, this anthology of nature poetry has been arranged seasonally – spring through to winter – and, within season, roughly thematically. No context or biographical information is given on the poets apart from birth and death years for those not living. Selections from Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare and W.B. Yeats thus share space with the work of contemporary and lesser-known poets. This is a similar strategy to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies, the ranging across time meant to suggest continuity in human engagement with the natural world. However, with a few exceptions (the above plus Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Inversnaid” are absolute classics, of course), the historical verse tends to be obscure, rhyming and sentimental; unfair to deem it all purple or doggerel, but sometimes bodies of work are forgotten for a reason. By contrast, I found many more standouts among the contemporary poets. Some favourites: “Cyanotype, by St Paul’s Cathedral” by Tamiko Dooley, “Eight Blue Notes” by Gillian Dawson (about eight species of butterfly), the gorgeously erotic “the bluebells are coming out & so am I” by Maya Blackwell, and “The Trees Don’t Know I’m Trans” by Eddy Quekett. It was also worthwhile to discover poems from other ancient traditions, such as haiku by Issa (“O Snail”) and wise aphoristic verse by Lao Tzu (“All things pass”). So, a bit of a mixed bag, but a nice introductory text for those newer to poetry.

With thanks to Saraband for the free copy for review.

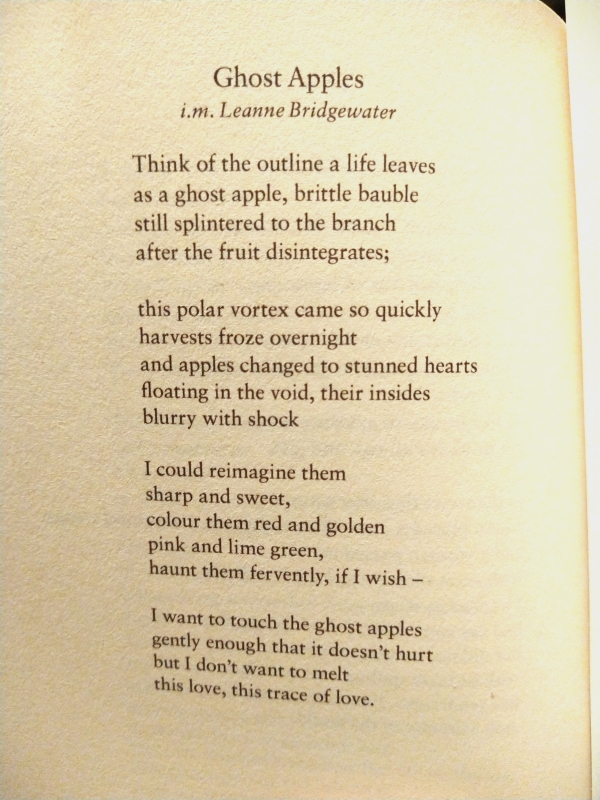

Dangerous Enough by Becky Varley-Winter (2023)

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

I requested this debut collection after hearing that it had been longlisted for the Laurel Prize for environmental poetry (funded by Simon Armitage, Poet Laureate). Varley-Winter crafts lovely natural metaphors for formative life experiences. Crows and wrens, foxes and fireflies, memories of a calf being born on a farm in Wales; gardens, greenhouses and long-lived orchids. These are the sorts of images that thread through poems about loss, parenting and the turmoil of lockdown. The last line or two of a poem is often especially memorable. It’s been months since I read this and I foolishly didn’t take any notes, so I haven’t retained more detail than that. But here is one shining example:

With thanks to Salt Publishing for the free copy for review.

20 Books of Summer, 14–16: Polly Atkin, Nan Shepherd and Susan Allen Toth

I’m still plugging away at the challenge. It’ll be down to the wire, but I should finish and review all 20 books by the 31st! Today I have a chronic illness memoir, a collection of poetry and prose pieces, and a reread of a cosy travel guide.

Some of Us Just Fall: On Nature and Not Getting Better by Polly Atkin (2023)

I was heartened to see this longlisted for the Wainwright Prize. It was a perfect opportunity to recognize the disabled/chronically ill experience of nature and the book achieves just what the award has recognised in recent years: the braiding together of life writing and place-based observation. (Wainwright has also done a great job on diversity this year: there are three books by BIPOC and five by women on the nature writing shortlist alone.)

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

Polly Atkin knew something was different about her body from a young age. She broke bones all the time, her first at 18 months when her older brother ran into her on his bicycle. But it wasn’t until her thirties that she knew what was wrong – Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and haemochromatosis – and developed strategies to mitigate the daily pain and the drains on her energy and mobility. “Correct diagnosis makes lives bearable,” she writes. “It gives you access to the right treatment. It gives you agency.”

The book assembles long-ish fragments, snippets from different points of her past alternating with what she sees on rambles near her home in Grasmere. She writes in some depth about Lake District literature: Thomas De Quincey as well as the Wordsworths – Atkin’s previous book is a biography of Dorothy Wordsworth that spotlights her experience with illness. In describing the desperately polluted state of Windermere, Atkin draws parallels with her condition (“Now I recognise my body as a precarious ecosystem”). Although she spurns the notion of the “Nature Cure,” swimming is a valuable therapy for her.

Theme justifies form here: “This is the chronic life, lived as repetition and variance, as sedimentation of broken moments, not as a linear progression.” For me, there was a bit too much particularity; if you don’t connect to the points of reference, there’s no way in and the danger arises of it all feeling indulgent. Besides, by the time I opened this I’d already read two Ehlers-Danlos memoirs (All My Wild Mothers by Victoria Bennett and Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal) and another reference soon came my way in The Invisible Kingdom by Meghan O’Rourke. So overfamiliarity was a problem. And by the time I forced myself to pick this off of my set-aside shelf and finish it, I’d read Nina Lohman’s stellar The Body Alone. For those newer to reading about chronic illness, though, especially if you also have an interest in the Lakes, it could be an eye-opener.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the free copy for review.

Selected Prose & Poetry by Nan Shepherd (2023)

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

I’d read and enjoyed Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, which has surged in popularity as an early modern nature writing classic thanks to Robert Macfarlane et al. I’m not sure I’d go as far as the executor of the Nan Shepherd Estate, though, who describes her in the Preface as “Taylor Swift in hiking boots.” The pieces reprinted here are from her one published book of poems, In the Cairngorms, and the mixed-genre collection Wild Geese. There is also a 28-page “novella,” Descent from the Cross. After World War I, Elizabeth, a workers’ rights organiser for a paper mill, marries a shell-shocked veteran who wants to write a book but isn’t sure he has either the genius or the dedication. It’s interesting that Shepherd would write about a situation where the wife has the economic upper hand, but the tragedy of the sickly failed author put me in mind of George Gissing or D.H. Lawrence, so didn’t feel fresh. Going by length alone, I would have called this a short story, but I understand why it would be designated a novella, for the scope.

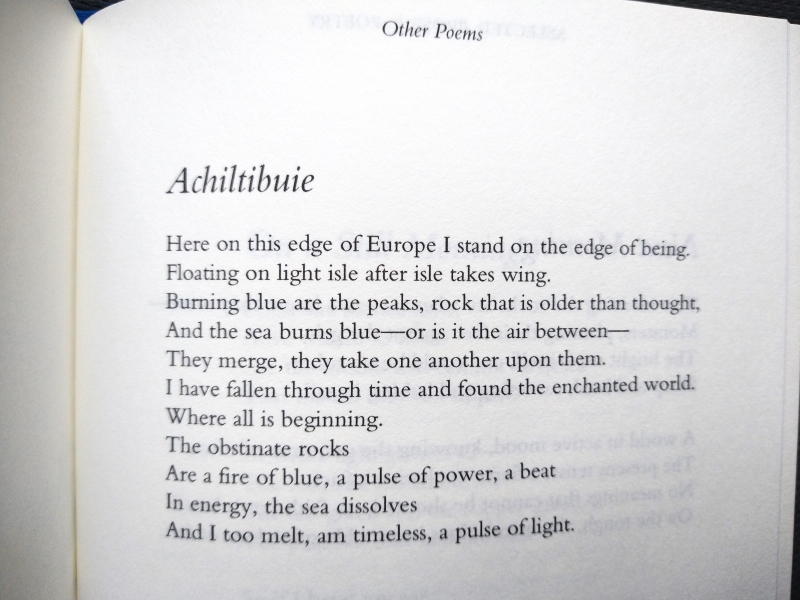

None of the miniature essays – field observations and character studies – stood out to me. About half of the book is given over to poetry. As with the nature writing, there is a feeling of mountain desolation. There are a lot of religious references and hints of the mystical, as in “The Bush,” which opens “In that pure ecstasy of light / The bush is burning bright. / Its substance is consumed away / And only form doth stay”. It’s a mixed bag: some feels very old-fashioned and sentimental, with every other line or, worse, every line rhyming, and some archaic wording and rather impenetrable Scots dialect. It could have been written 100 years before, by Robert Burns if not William Blake. But every so often there is a flash of brilliance. “Blackbird in Snow” is quite a nice one, and reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s “The Darkling Thrush.” I even found the cryptic lines from “Real Presence” that inspired a song on David Gray’s Skellig. My favourite poem by far was:

Overall, this didn’t engage me; it’s only for Shepherd fanatics and completists. (Won from Galileo Publishers in a Twitter giveaway)

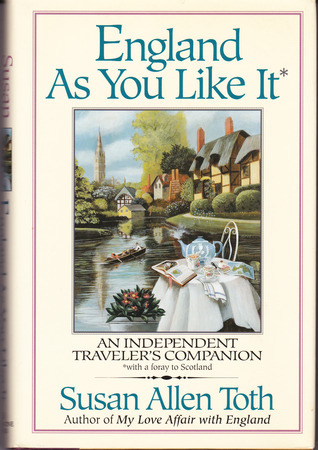

England As You Like It: An Independent Traveler’s Companion by Susan Allen Toth (1995)

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

A reread. As I was getting ready to go overseas for the first time in the summer of 2003, Toth’s trilogy of memoirs whetted my appetite for travel in Britain. (They’re on my Landmark Books in My Life, Part II list.) This is the middle book and probably the least interesting in that it mostly recounts stays in particular favourite locations, such as Dorset, the Highlands, and various sites in Cornwall. However, I’ve never forgotten her “thumbprint theory,” which means staying a week or more in an area no larger than her thumb covers on a large-scale map, driving an hour or less for day trips. Not for her those cram-it-all-in trips where you race through multiple countries in a week (I have American friends who did Paris, London and Rome within six days, or five countries in eight days; blame it on stingy vacation policies, I guess). Instead, she wants to really bed into one place and have the time to make serendipitous discoveries such as an obscure museum or a rare opening of a private garden.

I most liked the early general chapters about how to make air travel bearable, her obsession with maps, her preference for self-catering, and her tendency to take home edible souvenirs. Of course, all the “Floating Facts” are hopelessly out-of-date. This being the early to mid-1990s, she had to order paper catalogues to browse cottage options (I still did this for honeymoon prep in 2006–7) and make international phone calls to book accommodation. She recommends renting somewhere from the National Trust or Landmark Trust. Ordnance Survey maps could be special ordered from the British Travel Bookshop in New York City. Entry fees averaged a few pounds. It’s all so quaint! An Anglo-American time capsule of sorts. I’ve always sensed a kindred spirit in Toth, and those whose taste runs toward the old-fashioned will probably also find her a charming tour guide. I’ve also reviewed the third book, England for All Seasons. (Free from The Book Thing of Baltimore)

Rereading Of Mice and Men for #1937Club

A year club hosted by Karen and Simon is always a great excuse to read more classics. Between my shelves and the library, I had six options for 1937. But I started reading too late, and had too many books on the go, to finish more than one – a reread. No matter; it was a good one I was glad to revisit, and I’ll continue with the other reread at my own pace.

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

Are teenagers doomed to dislike the books they read in school? I think this must have been on the curriculum for 11th grade English. It was my third Steinbeck novella after The Red Pony and The Pearl, so to me it confirmed that he wrote contrived, depressing stuff with lots of human and animal suffering. Not until I read The Grapes of Wrath in college and East of Eden (THE Great American Novel) five years ago did I truly recognize Steinbeck’s greatness.

Are teenagers doomed to dislike the books they read in school? I think this must have been on the curriculum for 11th grade English. It was my third Steinbeck novella after The Red Pony and The Pearl, so to me it confirmed that he wrote contrived, depressing stuff with lots of human and animal suffering. Not until I read The Grapes of Wrath in college and East of Eden (THE Great American Novel) five years ago did I truly recognize Steinbeck’s greatness.

George and Lennie are itinerant farm workers in Salinas Valley, California. Lennie is a gentle giant, intellectually disabled and aware of his own strength when hauling sacks of barley but not when stroking mice and puppies. George looks after Lennie as a favour to Aunt Clara and they’re saving up to buy their own smallholding. This dream is repeated to the point of legend, somewhere between a bedtime story and scripture:

‘Someday—we’re gonna get the jack together and we’re gonna have a little house and a couple of acres an’ a cow and some pigs and—’ ‘An’ live off the fatta the lan’,’ Lennie shouted. ‘And have rabbits.’

They quickly settle in alongside the other ranch-hands and even convert two to their idyllic picture of independence. But the foreman, Curley, is a hothead and his bored would-be-starlet wife won’t stop roaming into the men’s quarters. No matter how much George tells Lennie to stay away from both of them, something is set in motion – an inevitable repeat of an incident from their previous employment that forced them to move on.

I remembered the main contours here but not the ultimate ending, and this time I appreciated the deliberate echoes and heavy foreshadowing (all that symbolism to write formulaic school essays about!): this is Shakespearean tragedy with the signs and stakes writ large against a limited background. Bar some paragraphs of scene-setting descriptions, it is like a play; no surprise it’s been filmed several times. (I wish I didn’t have danged John Malkovich in my head as Lennie; I can’t think of anyone else in that role, whereas Gary Sinise doesn’t necessarily epitomize George for me.) The characterization of the one Black character, Crooks, and the one woman are uncomfortably of their time. However, Crooks is given the dubious honour of conveying the bleak vision: “Nobody never gets to heaven, and nobody gets no land. It’s just in their head.” Like Hardy, Steinbeck knows what happens when the lower classes make the mistake of wanting too much. It’s a timeless tale of grit and desperation, the kind one can’t imagine not existing. (Public library)

Apposite listening: “The Great Defector” by Bell X1 (known for their quirky lyrics):

You’ve been teasing us farm boys

’til we start talking ’bout those rabbits, George

oh, won’t you tell us ’bout those rabbits, George?

Original rating (1999?): ![]()

My rating now: ![]()

Currently rereading: The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien – My father gave me this for Christmas when I was 10. I think I finally read it sometime in my later teens, about when the Lord of the Rings films were coming out. I’m on page 70 now. I’d forgotten just how funny Tolkien is about the set-in-his-ways Bilbo and his devotion to a cosy, quiet life. When he’s roped into a quest to reclaim a mountain hoard of treasure from a dragon – along with 13 dwarves and Gandalf the wizard – he realizes he has much discomfort and many a missed meal ahead of him.

DNFed: Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb – My second attempt with Hungarian literature, and I found it curiously similar to the other novel I’d read (Embers by Sandor Márai) in that much of it, at least the 50 pages I read, is a long story told by one character to another. In this case, Mihály, on his Italian honeymoon, tells his wife about his childhood best friends, a brother and sister. I wondered if I was meant to sense homoerotic attachment between Mihály and Tamás, which would appear to doom this marriage right at its outset. (Secondhand – Edinburgh charity shop, 2018)

DNFed: Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb – My second attempt with Hungarian literature, and I found it curiously similar to the other novel I’d read (Embers by Sandor Márai) in that much of it, at least the 50 pages I read, is a long story told by one character to another. In this case, Mihály, on his Italian honeymoon, tells his wife about his childhood best friends, a brother and sister. I wondered if I was meant to sense homoerotic attachment between Mihály and Tamás, which would appear to doom this marriage right at its outset. (Secondhand – Edinburgh charity shop, 2018)

Skimmed: Out of Africa by Karen Blixen – I enjoyed the prose style but could tell I’d need a long time to wade through the detail of her life on a coffee farm in Kenya, and would probably have to turn a blind eye to the expected racism of the anthropological observation of the natives. (Secondhand – Way’s in Henley, 2015)

Skimmed: Out of Africa by Karen Blixen – I enjoyed the prose style but could tell I’d need a long time to wade through the detail of her life on a coffee farm in Kenya, and would probably have to turn a blind eye to the expected racism of the anthropological observation of the natives. (Secondhand – Way’s in Henley, 2015)

Here’s hoping for a better showing next time!

(I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, and 1940 Club.)

The Booker Prize 2023 Ceremony

Yesterday evening Eleanor Franzen of Elle Thinks and I had the enormous pleasure of attending the Booker Prize awards ceremony at Old Billingsgate in London. I won tickets through “The Booker Prize Book Club” Facebook group, which launched just 10 or so weeks ago but has already garnered over 6000 members from around the world. They ran a competition for shortlist book reviews and probably did not attract nearly as many entries as they expected to. This probably worked to my advantage, but as it’s the only prize I can recall winning for my writing, I am going to take it as a compliment nonetheless! I submitted versions of my reviews of If I Survive You and Western Lane – the only shortlistees that I’ve read – and it was the latter that won us tickets.

We arrived at the venue 15 minutes before the doors opened, sheltering from the drizzle under an overhang and keeping a keen eye on arrivals (Paul Lynch and sodden Giller Prize winner Sarah Bernstein, her partner wearing both a kilt and their several-week-old baby). Elle has a gift for small talk and we had a nice little chat with Jonathan Escoffery and his 4th Estate publicist before they were whisked inside. His head was spinning from the events of the week, including being part of a Booker delegation that met Queen Camilla.

There was a glitzy atmosphere, with a photographer-surrounded red carpet and large banners for each shortlisted novel along the opposite wall, plus an exhibit of the hand-bound editions created for each book. We enjoyed some glasses of champagne and canapés (the haddock tart was the winner) and collared Eric Karl Anderson of Lonesome Reader. It was lovely to catch up with him and Eleanor and do plenty of literary celebrity spotting: Graeme Macrae Burnet, Eleanor Catton, judge Mary Jean Chan, Natalie Haynes, Alan Hollinghurst, Anna James, Jean McNeil, Johanna Thomas-Corr (literary editor of the Sunday Times) and Sarah Waters. Later we were also able to chat with Julianne Pachico, our Sunday Times Young Writer Award shadow panel winner from 2017. She has recently gotten married and released her third novel.

We were allocated to Table 11 in the front right corner. Also at our table were some Booker Prize editorial staff members, the other competition winner (for a video review) and her guest, an Instagram influencer, a Reading Agency employee, and several more people. The three-course dinner was of a very high standard for mass catering and the wine flowed generously. I thoroughly enjoyed my meal. Afterward we had a bit of time for taking red carpet photos and one of Eleanor with the banner for our predicted winner, Prophet Song.

Some of you may have watched the YouTube livestream, or listened to the Radio 4 live broadcast. Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s speech was a highlight. She spoke about the secret library at the Iranian prison where she was held for six years. Doctor Thorne by Anthony Trollope, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (there was a long waiting list among the prisoners and wardens, she said), and especially The Return by Hisham Matar meant a lot to her. From earlier on in the evening, I also enjoyed judge Adjoa Andoh’s dramatic reading of an excerpt from Possession in honour of the late Booker winner A.S. Byatt, and Shehan Karunatilaka’s tongue-in-cheek reflections on winning the Booker – he warned the next winner that they won’t write a word for a whole year.

There was a real variety of opinion in the room as to who would win. Earlier in the evening we’d spoken to people who favoured Western Lane, This Other Eden and The Bee Sting. But both Elle and I were convinced that Prophet Song would take home the trophy, and so it did. Despite his genuine display of shock, Paul Lynch was well prepared with an excellent speech in which he cited the apocrypha and Albert Camus. In a rapid-fire interview with host Samira Ahmed, he added that he can still remember sitting down and weeping after finishing The Mayor of Casterbridge, age 15 or 16, and hopes that his work might elicit similar emotion. I’m not sure that I plan on reading it myself, but from what I’ve heard it’s a powerfully convincing dystopian novel that brings political and social collapse home in a realistic way.

All in all, a great experience for which I am very grateful! (Thanks to Eleanor for all the photos.)

Have you read Prophet Song? Did you expect it to win the Booker Prize?

#NovNov23 Week 4, “The Short and the Long of It”: W. Somerset Maugham & Jan Morris

Hard to believe, but it’s already the final full week of Novellas in November and we have had 109 posts so far! This week’s prompt is “The Short and the Long of It,” for which we encourage you to pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics. The book pairings week of Nonfiction November is always a favourite (my 2023 contribution is here), so think of this as an adjacent – and hopefully fun – project. I came up with two pairs: one fiction and one nonfiction. In the first case, the longer book led me to read a novella, and it was vice versa for the second.

W. Somerset Maugham

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng (2023)

&

Liza of Lambeth by W. Somerset Maugham (1897)

I wasn’t a huge fan of The Garden of Evening Mists, but as soon as I heard that Tan Twan Eng’s third novel was about W. Somerset Maugham, I was keen to read it. Maugham is a reliably readable author; his books are clearly classic literature but don’t pose the stylistic difficulties I now experience with Dickens, Trollope et al. And yet I know that Booker Prize followers who had neither heard of nor read Maugham have enjoyed this equally. I’m surprised it didn’t make it past the longlist stage, as I found it as revealing of a closeted gay writer’s life and times as The Master (shortlisted in 2004) but wider in scope and more rollicking because of its less familiar setting, true crime plot and female narration.

The main action is set in 1921, as “Willie” Somerset Maugham and his secretary, Gerald, widely known to be his lover, rest from their travels in China and the South Seas via a two-week stay with Robert and Lesley Hamlyn at Cassowary House in Penang, Malaysia. Robert and Willie are old friends, and all three men fought in the First World War. Willie’s marriage to Syrie Wellcome (her first husband was the pharmaceutical tycoon) is floundering and he faces financial ruin after a bad investment. He needs a good story that will sell and gets one when Lesley starts recounting to him the momentous events of 1910, including a crisis in her marriage, volunteering at the party office of Chinese pro-democracy revolutionary Dr Sun Yat Sen, and trying to save her friend Ethel Proudlock from a murder charge.

It’s clever how Tan weaves all of this into a Maugham-esque plot that alternates between omniscient third-person narration and Lesley’s own telling. The glimpses of expat life and Asia under colonial rule are intriguing, and the scene-setting and atmosphere are sumptuous – worthy of the Merchant Ivory treatment. I was left curious to read more by and about Maugham, such as Selina Hastings’ biography. (Public library)

But for now I picked up one of the leather-bound Maugham books I got for free a few years ago. Amusingly, the novella-length Liza of Lambeth is printed in the same volume with the travel book On a Chinese Screen, which Maugham had just released when he arrived in Penang.

{SPOILERS AHEAD}

This was Maugham’s debut novel and drew on his time as a medical intern in the slums of London. In tone and content it falls almost perfectly between Dickens and Hardy, because on the one hand Liza Kemp and her neighbours are cheerful paupers even though they work in factories, have too many children and live in cramped quarters; on the other hand, alcoholism and domestic violence are rife, and the wages of sexual sin are death. All seems light to start with: an all-village outing to picnic at Chingford; pub trips; and harmless wooing as Liza rebuffs sweet Tom in favour of a flirtation with married Jim Blakeston.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

At the halfway point, I thought we were going full Tess of the d’Urbervilles – how is this not a rape scene?! Jim propositions her four times, ignoring her initial No and later quiet. “‘Liza, will yer?’ She still kept silence, looking away … Suddenly he shook himself, and closing his fist gave her a violent, swinging blow in the belly. ‘Come on,’ he said. And together they slid down into the darkness of the passage.” So starts their affair, which leads to Liza getting beaten up by Mrs Blakeston in the street and then dying of an infection after a miscarriage. The most awful character is Mrs Kemp, who spends the last few pages – while Liza is literally on her deathbed – complaining of her own hardships, congratulating herself on insuring her daughter’s life, and telling a blackly comic story about her husband’s corpse not fitting in his oak coffin and her and the undertaker having to jump on the lid to get it to close.

Liza isn’t entirely the stereotypical whore with the heart of gold, but she is a good-time girl (“They were delighted to have Liza among them, for where she was there was no dullness”) and I wonder if she could even have been a starting point for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion. Maugham’s rendering of the cockney accent is over-the-top –

“‘An’ when I come aht,’ she went on, ‘’oo should I see just passin’ the ’orspital but this ’ere cove, an’ ’e says to me, ‘Wot cheer,’ says ’e, ‘I’m goin’ ter Vaux’all, come an’ walk a bit of the wy with us.’ ‘Arright,’ says I, ‘I don’t mind if I do.’”

– but his characters are less caricatured than Dickens’s. And, imagine, even then there was congestion in London:

“They drove along eastwards, and as the hour grew later the streets became more filled and the traffic greater. At last they got on the road to Chingford, and caught up numbers of other vehicles going in the same direction—donkey-shays, pony-carts, tradesmen’s carts, dog-carts, drags, brakes, every conceivable kind of wheeled thing, all filled with people”

In short, this was a minor and derivative-feeling work that I wouldn’t recommend to those new to Maugham. He hadn’t found his true style and subject matter yet. Luckily, there’s plenty of other novels to try. (Free mall bookshop) [159 pages]

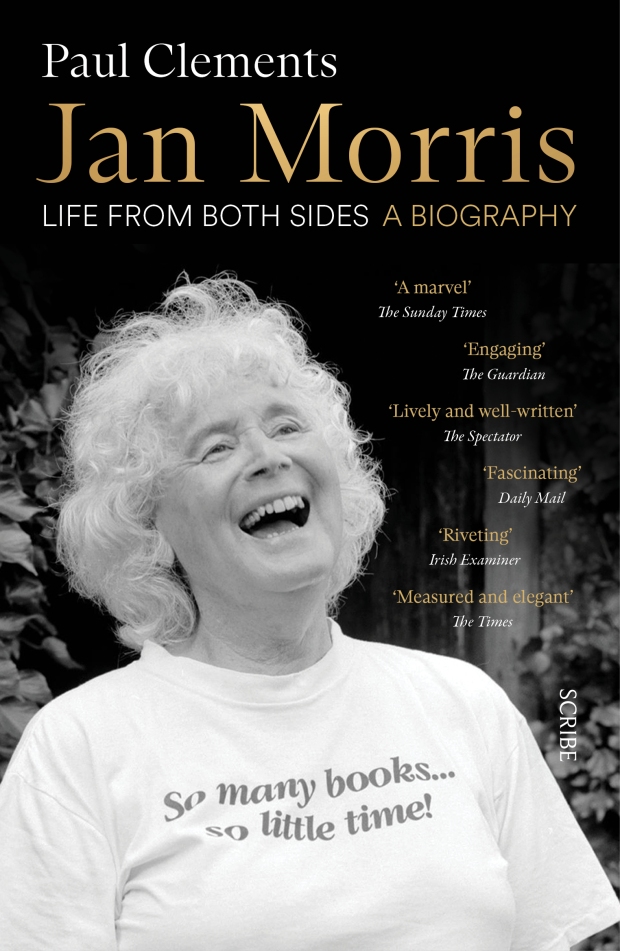

Jan Morris

Conundrum by Jan Morris (1974)

&

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides, A Biography by Paul Clements (2022)

Back in 2021, I reread and reviewed Conundrum during Novellas in November. It’s a short memoir that documents her spiritual journey towards her true identity – she was a trans pioneer and influential on my own understanding of gender. In his doorstopper of a biography, Paul Clements is careful to use female pronouns throughout, even when this is a little confusing (with Morris a choirboy, a soldier, an Oxford student, a father, and a member of the Times expedition that first summited Everest). I’m just over a quarter of the way through the book now. Morris left the Times before the age of 30, already the author of several successful travel books on the USA and the Middle East. I’ll have to report back via Love Your Library on what I think of this overall. At this point I feel like it’s a pretty workaday biography, comprehensive and drawing heavily on Morris’s own writings. The focus is on the work and the travels, as well as how the two interacted and influenced her life.

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Hardy’s Wives, Rituals, and Romcoms

Liz is hosting this week of Nonfiction November. For this prompt, the idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with three based on my recent reading:

Thomas Hardy’s Wives

On my pile for Novellas in November was a tiny book I’ve owned for nearly two decades but not read until now. It contains some of the backstory for an excellent historical novel I reviewed earlier in the year.

Some Recollections by Emma Hardy

&

The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry

The manuscript of Some Recollections is one of the documents Thomas Hardy found among his first wife’s things after her death in 1912. It is a brief (15,000-word) memoir of her early life from childhood up to her marriage – “My life’s romance now began.” Her middle-class family lived in Plymouth and moved to Cornwall when finances were tight. (Like the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice, you look at the house they lived in, and read about the servants they still employed, and think, “impoverished,” seriously?!) “Though trifling as they may seem to others all these memories are dear to me,” she writes. It’s true that most of these details seem inconsequential, of folk historical value but not particularly illuminating about the individual.

An exception is her account of her dealings with fortune tellers, who often went out of their way to give her good – and accurate – predictions, such as that she would marry a writer. It’s interesting to set this occult belief against the traditional Christian faith she espouses in her concluding paragraph, in which she insists an “Unseen Power of great benevolence directs my ways.” The other point of interest is her description of her first meeting with Hardy, who was sent to St. Juliot, where she was living with her parson brother-in-law and sister, as an architect’s assistant to begin repairs on the church. “I thought him much older than he was,” she wrote. As editor Robert Gittings notes, Hardy made corrections to the manuscript and in some places also changed the sense. Here Hardy gave proof of an old man’s continued vanity by adding “he being tired” after that line … but then partially rubbing it out. (Secondhand, Books for Amnesty, Reading, 2004) [64 pages]

The Chosen contrasts Emma’s idyllic mini memoir with her bitterly honest journals – Hardy read but then burned these, so Lowry had to recreate their entries based on letters and tone. But Some Recollections went on to influence his own autobiography, and to be published in a stand-alone volume by Oxford University Press. Gittings introduces the manuscript (complete with Emma’s misspellings and missing punctuation) and appends a selection of Hardy’s late poems based on his first marriage – this verse, too, is central to The Chosen.

Another recent nonfiction release on this subject matter that I learned about from a Shiny New Books review is Woman Much Missed: Thomas Hardy, Emma Hardy and Poetry by Mark Ford. I’d also like to read the forthcoming Hardy Women: Mother, Sisters, Wives, Muses by Paula Byrne (1 February 2024, William Collins).

Rituals

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton

&

The Rituals by Rebecca Roberts

Last month I reviewed this lovely Welsh novel about a woman who is an independent celebrant, helping people celebrate landmark events in their lives or cope with devastating losses by commemorating them through secular rituals.

Coming out in April 2024, The Ritual Effect is a Harvard Business School behavioral scientist’s wide-ranging study of how rituals differ from habits in that they are emotionally charged and lift everyday life into something special. Some of his topics are rites of passage in different cultures; musicians’ and sportspeople’s pre-performance routines; and the rituals we develop around food and drink, especially at the holidays. I’m just over halfway through this for an early Shelf Awareness review and I have been finding it fascinating.

Romantic Comedy

(As also featured in my August Six Degrees post)

What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding by Kristin Newman

&

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Romantic Comedy is probably still the most fun reading experience I’ve had this year. Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding is a lighthearted record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. (Newman even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s “Danny Horst Rule”: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”) Unfortunately, it got repetitive and raunchy. It was one of my 20 Books of Summer but I DNFed it halfway.

Book Serendipity, Mid-April through Early June

I call it “Book Serendipity” when two or more books that I read at the same time or in quick succession have something in common – the more bizarre, the better. This is a regular feature of mine every few months. Because I usually have 20–30 books on the go at once, I suppose I’m more prone to such incidents. The following are in roughly chronological order.

- Fishing with dynamite takes place in Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- Egg collecting (illegal!) is observed and/or discussed in Sea Bean by Sally Huband and The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth.

- Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know is quoted in What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma and Glowing Still by Sara Wheeler. I then bought a secondhand copy of the Levy on my recent trip to the States.

- “Piss-en-lit” and other folk names for dandelions are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

- Buttercups and nettles are mentioned in The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly and Springtime in Britain by Edwin Way Teale (and other members of the Ranunculus family, which includes buttercups, in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught).

- The speaker’s heart is metaphorically described as green in a poem in Lo by Melissa Crowe and The House of the Interpreter by Lisa Kelly.

- Discussion of how an algorithm can know everything about you in Tomb Sweeping by Alexandra Chang and I’m a Fan by Sheena Patel.

- A brother drowns in The Loved Ones: Essays to Bury the Dead by Madison Davis, What I’d Rather Not Think About by Jente Posthuma, and The Furrows by Namwali Serpell.

A few cases of a book recalling a specific detail from an earlier read:

- This metaphor in The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry links it to The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell, another work of historical fiction I’d read not long before: “He has further misgivings about the scalloped gilt bedside table, which wouldn’t look of place in the palazzo of an Italian poisoner.”

- This reference in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton links it back to Chase of the Wild Goose by Mary Louisa Gordon (could it be the specific book she had in mind? I suspect it was out of print in 1989, so it’s more likely it was Elizabeth Mavor’s 1971 biography The Ladies of Llangollen): “Do you have a book about those ladies, the eighteenth-century ones, who lived together in some remote place, but everyone knew them?”

- This metaphor in Things My Mother Never Told Me by Blake Morrison links it to The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry: “Moochingly revisiting old places, I felt like Thomas Hardy in mourning for his wife.”

- A Black family is hounded out of a majority-white area by harassment in The Education of Harriet Hatfield by May Sarton and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

Wartime escapees from prison camps are helped to freedom, including with the help of a German typist, in My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor and In Memoriam by Alice Winn.

- A scene of eating a deceased relative’s ashes in 19 Claws and a Black Bird by Agustina Bazterrica and The Loved Ones by Madison Davis.

- A girl lives with her flibbertigibbet mother and stern grandmother in “Wife Days,” one story from How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery.

- Macramé is mentioned in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain.

- A fascination with fractals in Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal and one story in Sidle Creek by Jolene McIlwain. They are also mentioned in one essay in These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- I found disappointed mentions of the fact that characters wear blackface in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town on the Prairie in Monsters by Claire Dederer and, the very next day, Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Moon jellyfish are mentioned in the Blood and Cord anthology edited by Abi Curtis, Floppy by Alyssa Graybeal, and Sea Bean by Sally Huband.

- A Black author is grateful to their mother for preparing them for life in a white world in the memoirs-in-essays I Can’t Date Jesus by Michael Arceneaux and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- The children’s book The Owl Who Was Afraid of the Dark by Jill Tomlinson is mentioned in The Jay, the Beech and the Limpetshell by Richard Smyth and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- The protagonist’s father brings home a tiger as a pet/object of display in The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell and The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller.

- Bloor Street, Toronto is mentioned in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and Ordinary Notes by Christina Sharpe.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s thinking about the stars is quoted in Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery and These Envoys of Beauty by Anna Vaught.

- Wondering whether a marine animal would be better off in captivity, where it could live much longer, in The Memory of Animals by Claire Fuller (an octopus) and Sea Bean by Sally Huband (porpoises).

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

Martha Gellhorn is mentioned in The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer and Monsters by Claire Dederer.

- Characters named June in “Indigo Run,” the novella-length story in How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman, and The Cats We Meet Along the Way by Nadia Mikail.

- “Explicate!” is a catchphrase uttered by a particular character in Girls They Write Songs About by Carlene Bauer and The Lake Shore Limited by Sue Miller.

- It’s mentioned that people used to get dressed up for going on airplanes in Fly Girl by Ann Hood and The Lights by Ben Lerner.

- Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn is a setting in The Lights by Ben Lerner and Grave by Allison C. Meier.

- Last year I read Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, in which Oregon Trail re-enactors (in a video game) die of dysentery; this is also a live-action plot point in “Pioneers,” one story in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow.

- A bunch (4 or 5) of Italian American sisters in Circling My Mother by Mary Gordon and Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano.

What’s the weirdest reading coincidence you’ve had lately?

The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry (2022)

“What’s lost when your idea of the other dies? He knows the answer: only the entire world.”

Elizabeth Lowry’s utterly immersive third novel, The Chosen, currently on the shortlist for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction*, examines Thomas Hardy’s relationship with his first wife, Emma Gifford. The main storyline is set in November–December 1912 and opens on the morning of Emma’s death at Max Gate, their Dorchester home of 27 years. The couple had long been estranged and effectively lived separate lives on different floors of the house, but instantly Hardy is struck with pangs of grief – and remorse for how he had treated Emma. (He would pour these emotions out into some of his most famous poems.)

That guilt is only compounded by what he finds in her desk: her short memoir, Some Recollections, with an account of their first meeting in Cornwall; and her journals going back two decades, wherein she is brutally honest about her husband’s failings and pretensions. “I expect nothing from him now & that is just as well – neither gratitude nor attention, love, nor justice. He belongs to the public & all my years of devotion count for nothing.” She describes him as little better than a jailor, and blames him for their lifelong childlessness.

It’s an exercise in self-flagellation, yet as weeks crawl by after her funeral, Hardy continues to obsessively read Emma’s “catalogue of her grievances.” In the fog of grief, he relives scenes his late wife documented – especially the composition and controversial publication of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Emma hoped to be his amanuensis and so share in the thrill of creation, but he nipped a potential reunion in the bud. Lowry intercuts these flashbacks with the central narrative in a way that makes Hardy feel like a bumbling old man; he has trouble returning to reality afterwards, and his sisters and the servants are concerned for him.

Hardy was that stereotypical figure: the hapless man who needs women around to do everything for him. Luckily, he’s surrounded by an abundance of strong female characters: his sister Kate, who takes temporary control of the household; his secretary, Florence Dugdale, who had been his platonic companion and before long became his second wife; even Emma’s money-grubbing niece, Lilian, who descends to mine her aunt’s wardrobe.

I particularly enjoyed Hardy’s literary discussions with Edmund Gosse, who urged him to temper the bleakness of his plots, and the stranger-than-fiction incident of a Chinese man visiting Hardy at home and telling him his own story of neglecting his wife and repenting his treatment of her after her death.

For anyone who’s read and loved Hardy’s major works, or visited his homes, this feels absolutely true to his life story, and so evocative of the places involved. I could picture every locale, from Stinsford churchyard to Emma’s attic bedroom. It was perfect reading for my short break in Dorset earlier in the month and brought back memories of the Hardy tourism I did at the end of my study abroad year in 2004. Although Hardy’s written words permeate the book, I was impressed to learn that Lowry invented all of Emma’s journal entries, based on feelings she had expressed in letters.

But there is something universal, of course, about a tale of waning romance, unexpected loss, and regret for all that is left undone. This is such a beautifully understated novel, perfectly convincing for the period but also timeless. It’s one to shelve alongside Winter by Christopher Nicholson, another favourite of mine about Hardy’s later life. ![]()

With thanks to riverrun (Quercus) for the free copy for review. The Chosen came out in paperback on 13 April.

*The winner will be announced on 15 June.