Doorstopper of the Month: The Stillness The Dancing (1985) by Wendy Perriam

When she read my review of As a God Might Be by Neil Griffiths, Liz Dexter suggested Wendy Perriam’s books as readalikes and very kindly sent me one to try: The Stillness The Dancing – a title whose lack of punctuation confused me until I discovered that it’s taken from a line of T. S. Eliot’s “East Coker”: “So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.” It took me nearly a year and a half to get around to it, but I’ve finally read my first Perriam (fairly autobiographical, it seems) and found it very striking and worthwhile.

The comparison with the Griffiths turned out to be apt: both are hefty, religion-saturated novels dwelling on themes of purpose, mysticism, asceticism, and the connection between the mind and body, especially when it comes to sex. Perriam’s protagonist is Morna Gordon, a 41-year-old translator. The end of her marriage was nearly as disorienting for her as the loss of her Catholic faith. Occasional chapters spotlight the perspective of the other women in this family line: Morna’s mother, Bea, who’s been a widow for as long as Morna has been alive and finally finds a vocation at an age when most people are retiring; and Morna’s daughter Chris, who’s tasting freedom before starting uni and settling down with her diver boyfriend, Martin.

The comparison with the Griffiths turned out to be apt: both are hefty, religion-saturated novels dwelling on themes of purpose, mysticism, asceticism, and the connection between the mind and body, especially when it comes to sex. Perriam’s protagonist is Morna Gordon, a 41-year-old translator. The end of her marriage was nearly as disorienting for her as the loss of her Catholic faith. Occasional chapters spotlight the perspective of the other women in this family line: Morna’s mother, Bea, who’s been a widow for as long as Morna has been alive and finally finds a vocation at an age when most people are retiring; and Morna’s daughter Chris, who’s tasting freedom before starting uni and settling down with her diver boyfriend, Martin.

When Morna accompanies Bea on a week-long religious retreat in the countryside, she meets David Anthony, a younger man she initially assumes is a priest. Here to deliver a lecture on miracles, he’s a shy scholar researching a seventh-century Celtic saint, Abban, who led an austere life on a remote Scottish island. Morna is instantly captivated by David’s intellectual passion, and in lieu of flirting offers to help him with his medieval translations. Still bruised by her divorce, she longs to make a move yet doesn’t want to scare David off. After 14 years of Neil telling her she was frigid, she’s startled to find herself in the role of sexual temptress.

Staid suburban England is contrasted with two very different locales: Saint Abban’s island and the outskirts of Los Angeles, where Morna and Chris travel for a few weeks in January so Chris can spend time with her father and meet his new family: (younger) wife Bunny and Chris’s four-year-old half-brother, Dean. California is “another world completely,” a fever dream of consumerism and excess, and Morna does things that are completely outside her comfort zone, like spending hours submerged in a sensory deprivation tank and breaking down in tears in the middle of Bunny’s women’s consciousness-raising circle.

The differences between England and California are exaggerated for comic effect in a way that reminded me of David Lodge’s Changing Places – but if for Chris it’s all about hedonistic self-expression, for Morna America is more of an existential threat, and she rushes back to be with David. There are several such pivotal moments when Morna flees one existence for another, often accompanied by a time of brain fog: alcohol, sleeping pills or grief disrupt her normal thought processes, as reflected in choppy, repetitive sentences.

I bristled slightly at the melodramatic nature of the final 60 pages, unsure to what extent the ending should be seen as altering the book’s overall message: Morna is denied a full transformation, but it seems she’s still on the spiritual path towards detachment from material things. Though still a lapsed Catholic, she finds some fresh meaning in the Church’s history and rituals. As her mother and daughter both embark on their new lives, her ongoing task is to figure out who she is apart from the connections that have defined her for so many years.

My favorite parts of the novel, not surprisingly, were Morna’s internal monologue – and her conversations with David – about faith and doubt. Perhaps I wasn’t wholeheartedly convinced that all the separately enjoyable components fit together, or that all the strands were fully followed through, but it’s an exuberant as well as a meditative work and I will certainly seek out more from Perriam.

Some favorite lines:

(Morna thinks) “If one had been exhorted all one’s girlhood to live for God alone, then how could one have purpose if He vanished?”

David: “I know our society shies away from any type of self-denial, regards it as neurotic or obsessional, but I disagree with that. Anything worth having is worth suffering for.”

Morna: “Are you still a Catholic? I know you said you believed in God, but that’s not the same, is it?” / David: “I’m still redefining all my terms. That can take a lifetime.”

Author note: Wendy Perriam’s name was completely new to me, though this was her 11th novel. Now in her 70s, she is still publishing fiction, with a crime novel released in 2017.

Page count: 536

My rating:

Library Checkout: July 2019

Lots of library books in progress or waiting in the wings; not so many that I’ve actually managed to read this month. I give links to reviews of any books that I haven’t already featured on the blog in some way, and ratings for all the ones I’ve read or skimmed. What have you been reading from your local library? Library Checkout runs on the last Monday of every month. I don’t have an official link-up system, but feel free to use this image in your post and to leave a link to your blog in the comments if you’ve taken part.

READ

- Exposure by Helen Dunmore

- City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert

- The Crossway by Guy Stagg

- Frankissstein: A Love Story by Jeanette Winterson

SKIMMED

- Flight Risk: The Highs and Lows of Life as a Doctor at Heathrow Airport by Dr. Stephanie Green

CURRENTLY READING

- How to Treat People: A Nurse’s Notes by Molly Case

- Our Place: Can We Save Britain’s Wildlife before It Is Too Late? by Mark Cocker

- An Angel at My Table by Janet Frame

- Sweet Sorrow by David Nicholls

- The Pine Islands by Marion Poschmann

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Time Song: Searching for Doggerland by Julia Blackburn

- How Do You Like Me Now? by Holly Bourne

- Once More We Saw Stars by Jayson Greene

- The Sun Does Shine by Anthony Ray Hinton

- Expectation by Anna Hope

- The Electricity of Every Living Thing: One Woman’s Walk with Asperger’s by Katherine May

- Because: A Lyric Memoir by Joshua Mensch

- I Want to Show You More by Jamie Quatro

- The Farm by Joanne Ramos

- The Hiding Game by Naomi Wood

ON HOLD, TO BE CHECKED OUT

- On Chapel Sands: My Mother and Other Missing Persons by Laura Cumming

- Three Women by Lisa Taddeo

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

- Golden Child by Claire Adam

- If Only I Could Tell You by Hannah Beckerman

- The Easternmost House: A Year of Life on the Edge of England by Juliet Blaxland

- The Science of Fate: Why Your Future Is More Predictable than You Think by Hannah Critchlow

- The Last Supper: A Summer in Italy by Rachel Cusk

- The Garden Jungle: Or Gardening to Save the Planet by Dave Goulson

- When All Is Said by Anne Griffin

- The Porpoise by Mark Haddon

- The Wall by John Lanchester

- The Man Who Saw Everything by Deborah Levy

- I Never Said I Loved You by Rhik Samadder

- Feel Free: Essays by Zadie Smith

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- Stroke: A 5% Chance of Survival by Ricky Monahan Brown

- How to Catch a Mole: And Find Yourself in Nature by Marc Hamer

RETURNED UNREAD

- Queenie by Candice Carty-Williams

- How to Fail: Everything I’ve Ever Learned from Things Going Wrong by Elizabeth Day

- The Years by Annie Ernaux

- The Summer Book by Tove Jansson

- Under the Camelthorn Tree: Raising a Family among Lions by Kate Nicholls

I lost interest in all of these, plus there were holds after me on the first three.

Does anything appeal from my stacks?

This Is Not a Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook

“There is no planet B. This is where we will live, or go extinct as a species.”

I’m periodically prone to melancholy musings on the impending end of the world (like here). Reading this punchy collection of 35 essays was a way of taking those feelings seriously and putting them to constructive use. You’ve likely heard of Extinction Rebellion: a peaceful environmental activism movement that began in the UK and has now spread worldwide, it demands that governments face the facts about the climate crisis and do something about it, now. Fittingly, the book is divided into two sections: “Tell the Truth” plainly sets out the basics of climate breakdown and the effects we expect to see, including the disproportionate toll it will have on the poor and marginalized, and on island nations like the Maldives; “Act Now” is a practical call to arms with pieces by politicians, economists and protest organizers.

I’m periodically prone to melancholy musings on the impending end of the world (like here). Reading this punchy collection of 35 essays was a way of taking those feelings seriously and putting them to constructive use. You’ve likely heard of Extinction Rebellion: a peaceful environmental activism movement that began in the UK and has now spread worldwide, it demands that governments face the facts about the climate crisis and do something about it, now. Fittingly, the book is divided into two sections: “Tell the Truth” plainly sets out the basics of climate breakdown and the effects we expect to see, including the disproportionate toll it will have on the poor and marginalized, and on island nations like the Maldives; “Act Now” is a practical call to arms with pieces by politicians, economists and protest organizers.

Not surprisingly, experts are calling for radical societal change: we must move away from the car culture; we cannot continue to equate success with economic growth; we must reorganize how cities function. “We are not looking at adjustments any more. It’s a complete overhaul,” Leeds University’s Professor of Urban Futures, Paul Chatterton, writes. But what did surprise me about reading This Is Not a Drill is that it’s not depressing. It’s actually rather exciting to see how many great minds and ordinary folk are aware of the climate crisis and working to mitigate it. We might not have political will at the highest levels, but grassroots movements involving just 3% of the citizenry have been shown to effect social change. I want to be part of that 3%. After I finished reading I signed up to ER’s mailing list, and though it’s not at all in my comfort zone, I’m going to consider taking part in their next public disruption.

I came away from this book with a feeling of camaraderie: we’re all in this together, and so we can only tackle it together. Post-apocalyptic fiction envisions violent, everyone-for-themselves scenarios, but it doesn’t have to be that way. ER demonstrations are said to be characterized by energy, music, laughter and good food. One word keeps appearing throughout the essays: “love.” There is righteous anger here, yes, but that’s outweighed by love – love of our planet, our only home, and the creatures it nurtures; love of the human race, the family that encompasses us all. While the authors are not unanimously optimistic, there is a sense that there is dignity in working towards positive change, whether or not we ultimately succeed. Plus, “It might just work,” former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams concludes in his afterword.

I came away from this book with a feeling of camaraderie: we’re all in this together, and so we can only tackle it together. Post-apocalyptic fiction envisions violent, everyone-for-themselves scenarios, but it doesn’t have to be that way. ER demonstrations are said to be characterized by energy, music, laughter and good food. One word keeps appearing throughout the essays: “love.” There is righteous anger here, yes, but that’s outweighed by love – love of our planet, our only home, and the creatures it nurtures; love of the human race, the family that encompasses us all. While the authors are not unanimously optimistic, there is a sense that there is dignity in working towards positive change, whether or not we ultimately succeed. Plus, “It might just work,” former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams concludes in his afterword.

If you feel hopeless when you think about the state of the environment, I encourage you to pick this up, even if you only skim through and read a handful of the essays. The handbook achieves a fine balance between academics and laypeople; forthright assertions and creative ideas; grief and enthusiasm. It’s also strikingly designed, with the pink cover matching the ER boat and heavy use of the sorts of recurring icons and slogans you might recognize from their banners: skulls and hourglasses share space with bees, birds, butterflies and a Tree of Life. My only real quibble is that I would have liked a short bio of each contributor, either at the close of each essay or in an appendix, because while a few of these authors are household names, many are not, and it would be useful to know their bona fides.

Don’t miss these pieces: “Climate Sorrow” by psychotherapist Susie Orbach, “A Political View” by Green Party MP Caroline Lucas, “A New Economics” by Oxbridge economist Kate Raworth, and “The Civil Resistance Model” by Roger Hallam of Extinction Rebellion.

Some favorite lines:

“Being human is not about individual survival or escape. It’s a team sport. Whatever future humans have, it will be together.” (from “Survival of the Fittest,” by American media theorist Douglas Rushkoff)

“It’s interesting and important to note that the people who are most effective are often the least attached to the effectiveness of their actions. Being detached from the outcome, and in love with the principles and the process, can help mitigate against burn-out.” (from “The Civil Resistance Model” by Roger Hallam)

“We may or may not escape a breakdown. But we can escape the toxicity of the mindset that has brought us here. And in so doing we can recover a humanity that is capable of real resilience.” (from the Afterword by Rowan Williams)

“if you are alive at this moment in history, it is because you are here to do a job. So what is your place in these times?” (from “What Is Your Place in These Times?” by Gail Bradbrook, co-founder of Extinction Rebellion)

My rating:

This Is Not a Drill was published on June 13th. My thanks to Penguin Random House for the free copy for review.

Too Male! (A Few Recent Reviews for Shiny New Books and TLS)

I tend to wear my feminism lightly; you won’t ever hear me railing about the patriarchy or the male gaze. But there have been five reads so far this year that had me shaking my head and muttering, “too male!” While aspects of these books were interesting, the macho attitude or near-complete dearth of women irked me. Two of them I’ve already written about here: Ernest Hemingway’s The Garden of Eden was a previous month’s classic and book club selection, while Chip Cheek’s Cape May was part of my reading in America. The other three I reviewed for Shiny New Books or the Times Literary Supplement; I give excerpts below, with links to visit the full reviews in two cases, plus ideas for a book or two by a woman that should help neutralize the bad taste these might leave.

Shiny New Books

The Way Home: Tales from a Life without Technology by Mark Boyle

Boyle lives without electricity in a wooden cabin on a smallholding in County Galway, Ireland. He speaks of technology as an addiction and letting go of it as a detoxification process. For him it was a gradual shift that took place at the same time as he was moving away from modern conveniences. The Way Home is split into seasonal sections in which the author’s past and present intermingle. The writing consciously echoes Henry David Thoreau’s. Without even considering the privilege that got Boyle to the point where he could undertake this experiment, though, there are a couple of problems with this particular back-to-nature model. One is that it is a very male enterprise. Another is that Boyle doesn’t really have the literary chops to add much to the canon. Few of us could do what he has done, whether because of medical challenges, a lack of hands-on skills or family commitments. Still, the book is worth engaging with. It forces you to question your reliance on technology and ask whether making life easier is really a valuable goal.

Boyle lives without electricity in a wooden cabin on a smallholding in County Galway, Ireland. He speaks of technology as an addiction and letting go of it as a detoxification process. For him it was a gradual shift that took place at the same time as he was moving away from modern conveniences. The Way Home is split into seasonal sections in which the author’s past and present intermingle. The writing consciously echoes Henry David Thoreau’s. Without even considering the privilege that got Boyle to the point where he could undertake this experiment, though, there are a couple of problems with this particular back-to-nature model. One is that it is a very male enterprise. Another is that Boyle doesn’t really have the literary chops to add much to the canon. Few of us could do what he has done, whether because of medical challenges, a lack of hands-on skills or family commitments. Still, the book is worth engaging with. It forces you to question your reliance on technology and ask whether making life easier is really a valuable goal.

The Remedy: Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies, which I’m currently reading for a TLS review. Davies crosses Boyle’s Thoreauvian language about solitude and a place in nature with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during the ongoing housing crisis, she moves into the shed near Land’s End that once served as her father’s architecture office and embarks on turning it into a home.

The Remedy: Homesick: Why I Live in a Shed by Catrina Davies, which I’m currently reading for a TLS review. Davies crosses Boyle’s Thoreauvian language about solitude and a place in nature with a Woolfian search for a room of her own. Penniless during the ongoing housing crisis, she moves into the shed near Land’s End that once served as her father’s architecture office and embarks on turning it into a home.

Doggerland by Ben Smith

This debut novel has just two main characters: ‘the old man’ and ‘the boy’ (who’s not really a boy anymore), who are stationed on an enormous offshore wind farm. The distance from the present day is indicated in slyly throwaway comments like “The boy didn’t know what potatoes were.” Smith poses questions about responsibility and sacrifice, and comments on modern addictions and a culture of disposability. He has certainly captured something of the British literary zeitgeist. From page to page, though, Doggerland grew tiresome for me. There is a lot of maritime vocabulary and technical detail about supplies and maintenance. The location is vague and claustrophobic, the pace is usually slow, and there are repetitive scenes and few conversations. To an extent, this comes with the territory. But it cannot be ignored that this is an entirely male world. Fans of the themes and style of The Old Man and the Sea and The Road will get on best with Smith’s writing. I most appreciated the moments of Beckettian humor in the dialogue and the poetic interludes that represent human history as a blip in the grand scheme of things.

This debut novel has just two main characters: ‘the old man’ and ‘the boy’ (who’s not really a boy anymore), who are stationed on an enormous offshore wind farm. The distance from the present day is indicated in slyly throwaway comments like “The boy didn’t know what potatoes were.” Smith poses questions about responsibility and sacrifice, and comments on modern addictions and a culture of disposability. He has certainly captured something of the British literary zeitgeist. From page to page, though, Doggerland grew tiresome for me. There is a lot of maritime vocabulary and technical detail about supplies and maintenance. The location is vague and claustrophobic, the pace is usually slow, and there are repetitive scenes and few conversations. To an extent, this comes with the territory. But it cannot be ignored that this is an entirely male world. Fans of the themes and style of The Old Man and the Sea and The Road will get on best with Smith’s writing. I most appreciated the moments of Beckettian humor in the dialogue and the poetic interludes that represent human history as a blip in the grand scheme of things.

The Remedy: I’m not a big fan of dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction in general, but a couple of the best such novels that I’ve read by women are Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins.

The Remedy: I’m not a big fan of dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction in general, but a couple of the best such novels that I’ve read by women are Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel and Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins.

Times Literary Supplement

The Knife’s Edge: The Heart and Mind of a Cardiac Surgeon by Stephen Westaby

In this somewhat tepid follow-up to Fragile Lives, Westaby’s bravado leaves a bad taste and dilutes the work’s ostensibly confessional nature. He has a good excuse, he argues: a head injury incurred while playing rugby in medical school transformed him into a risk taker. It’s widely accepted that such boldness may be a boon in a discipline that requires quick thinking and decisive action. So perhaps it’s no great problem to have a psychopath as your surgeon. But how about a sexist? Westaby’s persistent references to women staff as “lady GP” and “registrar lady” don’t mitigate surgeons’ macho reputation. It’s a shame to observe such casual sexism, because it’s clear Westaby felt deeply for his patients of any gender. And yet any talk of empathy earns his derision. It seems the specific language of compassion is a roadblock for him. The book is strongest when the author recreates dramatic sequences based on several risky surgeries. Alas, at its close he sounds bitter, and the NHS bears the brunt of his anger. Compared to Fragile Lives, one of my favorite books of 2017, this gives the superhero surgeon feet of clay. But it’s a lot less pleasing to read. (Forthcoming in TLS.)

In this somewhat tepid follow-up to Fragile Lives, Westaby’s bravado leaves a bad taste and dilutes the work’s ostensibly confessional nature. He has a good excuse, he argues: a head injury incurred while playing rugby in medical school transformed him into a risk taker. It’s widely accepted that such boldness may be a boon in a discipline that requires quick thinking and decisive action. So perhaps it’s no great problem to have a psychopath as your surgeon. But how about a sexist? Westaby’s persistent references to women staff as “lady GP” and “registrar lady” don’t mitigate surgeons’ macho reputation. It’s a shame to observe such casual sexism, because it’s clear Westaby felt deeply for his patients of any gender. And yet any talk of empathy earns his derision. It seems the specific language of compassion is a roadblock for him. The book is strongest when the author recreates dramatic sequences based on several risky surgeries. Alas, at its close he sounds bitter, and the NHS bears the brunt of his anger. Compared to Fragile Lives, one of my favorite books of 2017, this gives the superhero surgeon feet of clay. But it’s a lot less pleasing to read. (Forthcoming in TLS.)

The Remedy: I’m keen to read Direct Red by Gabriel Weston, a memoir by a female surgeon.

The Remedy: I’m keen to read Direct Red by Gabriel Weston, a memoir by a female surgeon.

(Crikey! This was my 600th blog post.)

Classic of the Month: Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell (1933)

I’d of course read Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, but this was my first taste of George Orwell’s nonfiction. It was his first book, published when he was 30, and is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. I started it on the Eurostar between London and Paris and have enjoyed dipping into it over the past couple of weeks. I most appreciated the first two-thirds, in which Orwell is working as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Chapter 3 is a masterful piece of writing that, with its second-person address, puts the reader right into this desperate situation with him. The matter-of-fact words about poverty and hunger are incisive:

Hunger reduces one to an utterly spineless, brainless condition, more like the after-effects of influenza than anything else. It is as though one had turned into a jellyfish, or as though all one’s blood had been pumped out and luke-warm water substituted. Complete inertia is my chief memory of hunger

Two bad days followed. We had only sixty centimes left, and we spent it on half a pound of bread, with a piece of garlic to rub it with. The point of rubbing garlic on bread is that the taste lingers and gives one the illusion of having fed recently.

It is disagreeable to eat out of a newspaper on a public seat, especially in the Tuileries, which are generally full of pretty girls, but I was too hungry to care.

Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities. His pen portraits of those he associates with – Boris, a former captain in the Russian Army who is always coming up with new money-making schemes in Paris; Paddy, a tramp he falls in with in London; and Bozo, a “screever” (street painter) who “managed to keep his brain intact and alert, and so nothing could make him succumb to poverty” – are glistening passages enhanced by recreated dialogue. There are a few asides, such as a chapter about London slang and swearing, that break up the flow, and I might have liked more context about Orwell’s earlier and later life – how he slipped into poverty and how he worked his way out of it again – but he more than succeeds in his aim of exposing the truth of what it was like to be poor at that time.

Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities. His pen portraits of those he associates with – Boris, a former captain in the Russian Army who is always coming up with new money-making schemes in Paris; Paddy, a tramp he falls in with in London; and Bozo, a “screever” (street painter) who “managed to keep his brain intact and alert, and so nothing could make him succumb to poverty” – are glistening passages enhanced by recreated dialogue. There are a few asides, such as a chapter about London slang and swearing, that break up the flow, and I might have liked more context about Orwell’s earlier and later life – how he slipped into poverty and how he worked his way out of it again – but he more than succeeds in his aim of exposing the truth of what it was like to be poor at that time.

Depressingly, though, this is not merely a period piece: well over 80 years later, the poor are still in danger of homelessness and enslavement to low wages and zero-hours contracts. No doubt it is still what Orwell refers to as a “dismal, demoralizing way of life,” and the poor “are ordinary human beings … if they are worse than other people it is the result and not the cause of [that] way of life.”

Our town has its fair share of the down-and-out, as was brought home to me just yesterday. My husband had an unpleasant encounter with a group of them when he tried remonstrating with a man who was cutting flowers in the community garden we’ve volunteered our time to create – the very day before the Britain in Bloom competition! When I dropped by later to help get the garden tidy for judging, they were still hanging about on the other side of the canal, smoking and drinking. Then I spotted with them an older woman who goes to our church. I’ve broken bread with her on a regular basis. She borrowed a couple of books from the theological library last week. And she must be a hair’s breadth away from homelessness, if not actually homeless. It felt like a wake-up call, a reminder that these people whose lives seem so hopelessly foreign are not as distant or as different as we might like to think.

George Orwell’s 1943 press photo. Branch of the National Union of Journalists (BNUJ). [Public domain]

My rating:

Next month: The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley

The Art of Mindful Reading by Ella Berthoud

Ella Berthoud is one of the bibliotherapists at the School of Life in London and co-author of The Novel Cure. (I wrote about my bibliotherapy session with her in this post.) For her contribution to a Leaping Hare Press series on mindfulness – whose titles range from The Mindful Art of Wild Swimming to Mindfulness and the Journey of Bereavement – she’s thought deeply about how reading can be an active, deliberate practice rather than a time of passive receiving or entertainment. Through handy exercises and quirky tips she encourages readers to take stock of how they read and to become more aware of each word on the page.

To start with, a close reading exercise using a passage from Alice in Wonderland invites you to find out whether you’re an auditory, visual or kinesthetic reader. I learned that I’m a cross between auditory and visual: I hear every word aloud in my head, but I also picture the scenes, usually unfolding in black and white in settings that are familiar to me (my childhood best friend’s home used to be a common backdrop, for instance). The book then discusses ways to incorporate reading into daily life, from breakfast to bedtime and from a favorite chair to the crook of a tree, and how to combine it with other activities. I will certainly be trying out the reading yoga poses!

As I discovered at my bibliotherapy appointment, Ella is passionate about getting people reading in as many different ways as possible. That can include listening to audiobooks, reading aloud with a partner, or reading silently but in company with other people. She also surveys the many ways there are of sharing an enthusiasm for books nowadays, such as Book Crossing, book clubs and Little Free Libraries.

Although she acknowledges the place of e-readers and smartphones, Ella generally describes reading as a tactile experience, and insists on the importance of keeping a print reading journal as well as a ‘Golden Treasury’ of favorite passages, two strategies that will combat the tendency to forget a book as soon as you’ve finished it.

Some of her suggestions of what to do with physical books are beyond the pale for me – such as using a knife to slice a daunting doorstopper into more manageable chunks, or beating up a much-hyped book to “rob [it] of its glamour and gloss, and bring it down from its pedestal to a more humble state, a place where you can read it in comfort” – but there are ideas here to suit every kind of reader. Take a quick break between novels and use this book to think about how you read and in what ways you could improve or intensify the experience.

Favorite passages:

“As a bibliotherapist, I believe that every novel you read shapes the person that you are, speaking to you on a deep, unconscious level, and altering your very nature with the ideas that it shows you.”

“I often find that people imagine reading fiction is a self-indulgent thing to do, and that they ought to be doing something else. Much research has been conducted into the benefits of reading fiction, which deepens your empathy and emotional intelligence, helps with making important life decisions and allows your brain to rest. Research has shown that reading provides as much relaxation as meditation”

My rating:

With thanks to Leaping Hare Press for the free copy for review.

My Most Anticipated Releases of the Second Half of 2019

Although over 90 books from the second half of the year are already on my radar, I’ve managed to narrow it down to the 15 July to November releases that I’m most excited about. I have access to a few of these already, and most of the rest I will try requesting as soon as I’m back from Milan. (These are given in release date order within thematic sections; the quoted descriptions are from the publisher blurbs on Goodreads.)

[By the way, here’s how I did with my most anticipated releases of the first half of the year:

- 16 out of 30 read; of those 9 were somewhat disappointing (i.e., 3 stars or below) – This is such a poor showing! Is it a matter of my expectations being too high?

- 10 I still haven’t managed to find

- 1 print review copy arrived recently

- 1 I have on my Kindle to read

- 1 I skimmed

- 1 I lost interest in]

Fiction

The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal [July 23, Pamela Dorman Books] Stradal’s Kitchens of the Great Midwest (2015) is one of my recent favorites. This one has a foodie theme again, and sounds a lot like Louise Miller’s latest – two sisters: a baker of pies and a founder of a small brewery. “Here we meet a cast of lovable, funny, quintessentially American characters eager to make their mark in a world that’s often stacked against them.”

The Lager Queen of Minnesota by J. Ryan Stradal [July 23, Pamela Dorman Books] Stradal’s Kitchens of the Great Midwest (2015) is one of my recent favorites. This one has a foodie theme again, and sounds a lot like Louise Miller’s latest – two sisters: a baker of pies and a founder of a small brewery. “Here we meet a cast of lovable, funny, quintessentially American characters eager to make their mark in a world that’s often stacked against them.”

Hollow Kingdom by Kira Jane Buxton [August 6, Grand Central Publishing / Headline Review] As soon as I heard that this was narrated by a crow, I knew I was going to have to read it. (And the Seattle setting also ties in with Lyanda Lynn Haupt’s book.) “Humanity’s extinction has seemingly arrived, and the only one determined to save it is a foul-mouthed crow whose knowledge of the world around him comes from his TV-watching education.”

Hollow Kingdom by Kira Jane Buxton [August 6, Grand Central Publishing / Headline Review] As soon as I heard that this was narrated by a crow, I knew I was going to have to read it. (And the Seattle setting also ties in with Lyanda Lynn Haupt’s book.) “Humanity’s extinction has seemingly arrived, and the only one determined to save it is a foul-mouthed crow whose knowledge of the world around him comes from his TV-watching education.”

Inland by Téa Obreht [August 13, Random House / Weidenfeld & Nicolson] However has it been eight years since her terrific debut novel?! “In the lawless, drought-ridden lands of the Arizona Territory in 1893, two extraordinary lives collide. … [L]yrical, and sweeping in scope, Inland subverts and reimagines the myths of the American West.” The synopsis reminds me of Eowyn Ivey’s latest.

Inland by Téa Obreht [August 13, Random House / Weidenfeld & Nicolson] However has it been eight years since her terrific debut novel?! “In the lawless, drought-ridden lands of the Arizona Territory in 1893, two extraordinary lives collide. … [L]yrical, and sweeping in scope, Inland subverts and reimagines the myths of the American West.” The synopsis reminds me of Eowyn Ivey’s latest.

A Door in the Earth by Amy Waldman [August 27, Little, Brown and Company] I loved The Submission, Waldman’s 2011 novel about a controversial (imagined) 9/11 memorial. “Parveen Shamsa, a college senior in search of a calling, feels pulled between her charismatic and mercurial anthropology professor and the comfortable but predictable Afghan-American community in her Northern California hometown [and] travels to a remote village in the land of her birth to join the work of his charitable foundation.” (NetGalley download)

A Door in the Earth by Amy Waldman [August 27, Little, Brown and Company] I loved The Submission, Waldman’s 2011 novel about a controversial (imagined) 9/11 memorial. “Parveen Shamsa, a college senior in search of a calling, feels pulled between her charismatic and mercurial anthropology professor and the comfortable but predictable Afghan-American community in her Northern California hometown [and] travels to a remote village in the land of her birth to join the work of his charitable foundation.” (NetGalley download)

Bloomland by John Englehardt [September 10, Dzanc Books] “Bloomland opens during finals week at a fictional southern university, when a student walks into the library with his roommate’s semi-automatic rifle and opens fire. In this richly textured debut, Englehardt explores how the origin and aftermath of the shooting impacts the lives of three characters.” (print review copy from publisher)

Bloomland by John Englehardt [September 10, Dzanc Books] “Bloomland opens during finals week at a fictional southern university, when a student walks into the library with his roommate’s semi-automatic rifle and opens fire. In this richly textured debut, Englehardt explores how the origin and aftermath of the shooting impacts the lives of three characters.” (print review copy from publisher)

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett [September 25, Harper / Bloomsbury UK] I’m more a fan of Patchett’s nonfiction, but will keep reading her novels thanks to Commonwealth. “At the end of the Second World War, Cyril Conroy combines luck and a single canny investment to begin an enormous [Philadelphia] real estate empire … Set over … five decades, The Dutch House is a dark fairy tale about two smart people who cannot overcome their past.”

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett [September 25, Harper / Bloomsbury UK] I’m more a fan of Patchett’s nonfiction, but will keep reading her novels thanks to Commonwealth. “At the end of the Second World War, Cyril Conroy combines luck and a single canny investment to begin an enormous [Philadelphia] real estate empire … Set over … five decades, The Dutch House is a dark fairy tale about two smart people who cannot overcome their past.”

Medical themes

Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?: Big Questions from Tiny Mortals about Death by Caitlin Doughty [September 10, W.W. Norton / September 19, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] I’ve read Doughty’s previous books about our modern attitude towards mortality and death customs around the world. She’s wonderfully funny and iconoclastic. Plus, how can you resist this title?! Although it sounds like it’s geared towards children, I’ll still read the book. “Doughty blends her mortician’s knowledge of the body and the intriguing history behind common misconceptions … to offer factual, hilarious, and candid answers to thirty-five … questions.”

Will My Cat Eat My Eyeballs?: Big Questions from Tiny Mortals about Death by Caitlin Doughty [September 10, W.W. Norton / September 19, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] I’ve read Doughty’s previous books about our modern attitude towards mortality and death customs around the world. She’s wonderfully funny and iconoclastic. Plus, how can you resist this title?! Although it sounds like it’s geared towards children, I’ll still read the book. “Doughty blends her mortician’s knowledge of the body and the intriguing history behind common misconceptions … to offer factual, hilarious, and candid answers to thirty-five … questions.”

The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care by Anne Boyer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux] “A week after her forty-first birthday, the acclaimed poet Anne Boyer was diagnosed with highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer. … A genre-bending memoir in the tradition of The Argonauts, The Undying will … show you contemporary America as a thing both desperately ill and occasionally, perversely glorious.” (print review copy from publisher)

The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care by Anne Boyer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux] “A week after her forty-first birthday, the acclaimed poet Anne Boyer was diagnosed with highly aggressive triple-negative breast cancer. … A genre-bending memoir in the tradition of The Argonauts, The Undying will … show you contemporary America as a thing both desperately ill and occasionally, perversely glorious.” (print review copy from publisher)

From the author’s Twitter page.

Breaking and Mending: A doctor’s story of burnout and recovery by Joanna Cannon [September 26, Wellcome Collection] I haven’t gotten on with Cannon’s fiction, but a memoir should hit the spot. “A frank account of mental health from both sides of the doctor-patient divide, from the bestselling author of The Trouble with Goats and Sheep and Three Things About Elsie, based on her own experience as a doctor working on a psychiatric ward.”

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson [October 3, Doubleday / Transworld] His last few books have been somewhat underwhelming, but I’d read Bryson on any topic. He’s earned a reputation for making history, science and medicine understandable to laymen. “Full of extraordinary facts and astonishing stories, The Body: A Guide for Occupants is a brilliant, often very funny attempt to understand the miracle of our physical and neurological makeup.”

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson [October 3, Doubleday / Transworld] His last few books have been somewhat underwhelming, but I’d read Bryson on any topic. He’s earned a reputation for making history, science and medicine understandable to laymen. “Full of extraordinary facts and astonishing stories, The Body: A Guide for Occupants is a brilliant, often very funny attempt to understand the miracle of our physical and neurological makeup.”

The Depositions: New and Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be by Thomas Lynch [November 26, W.W. Norton] Lynch is such an underrated writer. A Michigan undertaker, he crafts essays and short stories about small-town life, the Irish-American experience and working with the dead. I discovered him through Greenbelt Festival some years back and have read three of his books. Some of what I’ve already read will likely be repeated here, but will be worth a second look anyway.

The Depositions: New and Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be by Thomas Lynch [November 26, W.W. Norton] Lynch is such an underrated writer. A Michigan undertaker, he crafts essays and short stories about small-town life, the Irish-American experience and working with the dead. I discovered him through Greenbelt Festival some years back and have read three of his books. Some of what I’ve already read will likely be repeated here, but will be worth a second look anyway.

Other Nonfiction

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell [August 29, Profile Books] The Diary of a Bookseller was a treat in 2017. I’ve read the first two-thirds of this already while in Milan, and I wish I was in Wigtown instead! This sequel picks up in 2015 and is very much more of the same – the daily routines of buying and selling books and being out and about in a small town – so it’s up to you whether that sounds boring or comforting. I’m finding it strangely addictive. (NetGalley download)

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell [August 29, Profile Books] The Diary of a Bookseller was a treat in 2017. I’ve read the first two-thirds of this already while in Milan, and I wish I was in Wigtown instead! This sequel picks up in 2015 and is very much more of the same – the daily routines of buying and selling books and being out and about in a small town – so it’s up to you whether that sounds boring or comforting. I’m finding it strangely addictive. (NetGalley download)

We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / October 10, Hamish Hamilton] Foer’s Eating Animals (2009) was a hard-hitting argument against eating meat. In this follow-up he posits that meat-eating is the single greatest contributor to climate change. “With his distinctive wit, insight and humanity, Jonathan Safran Foer presents this essential debate as no one else could, bringing it to vivid and urgent life, and offering us all a much-needed way out.”

We Are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast by Jonathan Safran Foer [September 17, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / October 10, Hamish Hamilton] Foer’s Eating Animals (2009) was a hard-hitting argument against eating meat. In this follow-up he posits that meat-eating is the single greatest contributor to climate change. “With his distinctive wit, insight and humanity, Jonathan Safran Foer presents this essential debate as no one else could, bringing it to vivid and urgent life, and offering us all a much-needed way out.”

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie [September 19, Sort of Books] Jamie is a Scottish poet who writes exquisite essays about the natural world. I’ve read her two previous essay collections, Findings and Sightlines, as well as a couple of volumes of her poetry. “From the thawing tundra linking a Yup’ik village in Alaska to its hunter-gatherer past to the shifting sand dunes revealing the impressively preserved homes of neolithic farmers in Scotland, Jamie explores how the changing natural world can alter our sense of time.”

Surfacing by Kathleen Jamie [September 19, Sort of Books] Jamie is a Scottish poet who writes exquisite essays about the natural world. I’ve read her two previous essay collections, Findings and Sightlines, as well as a couple of volumes of her poetry. “From the thawing tundra linking a Yup’ik village in Alaska to its hunter-gatherer past to the shifting sand dunes revealing the impressively preserved homes of neolithic farmers in Scotland, Jamie explores how the changing natural world can alter our sense of time.”

Unfollow by Megan Phelps-Roper [October 8, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / riverrun] Ties in with my special interest in women’s religious memoirs. “In November 2012, at the age of twenty-six, [Phelps-Roper] left [Westboro Baptist Church], her family, and her life behind. Unfollow is a story about the rarest thing of all: a person changing their mind. It is a fascinating insight into a closed world of extreme belief, a biography of a complex family, and a hope-inspiring memoir of a young woman finding the courage to find compassion.”

Unfollow by Megan Phelps-Roper [October 8, Farrar, Straus and Giroux / riverrun] Ties in with my special interest in women’s religious memoirs. “In November 2012, at the age of twenty-six, [Phelps-Roper] left [Westboro Baptist Church], her family, and her life behind. Unfollow is a story about the rarest thing of all: a person changing their mind. It is a fascinating insight into a closed world of extreme belief, a biography of a complex family, and a hope-inspiring memoir of a young woman finding the courage to find compassion.”

Which of these do you want to read, too?

What other upcoming 2019 titles are you looking forward to?

Three Recommended July Releases: Starling Days, Hungry, Supper Club

While very different, these three books tie together nicely with their themes of the hunger for food, adventure and/or love.

Starling Days by Rowan Hisayo Buchanan

(Coming on July 11th from Sceptre [UK])

Buchanan’s second novel reprises many of the themes from her first, Harmless Like You, including art, mental illness, and having one’s loyalties split across countries and cultures. Oscar and Mina have been together for over a decade, but their marriage got off to a bad start six months ago: on their wedding night Mina took an overdose, and Oscar was lucky to find her in time. The novel begins and ends with her contemplating suicide again; in between, Oscar takes her from New York City to England, where he grew up, for a change of scenery and to work on getting his father’s London flats ready to sell. For Mina, an adjunct professor and Classics tutor, it will be labeled a period of research on her monograph about the rare women who survive in Greek and Roman myth. But when work for his father’s Japanese import company takes Oscar back to New York, Mina is free to pursue her fascination with Phoebe, the sister of Oscar’s childhood friend.

Buchanan’s second novel reprises many of the themes from her first, Harmless Like You, including art, mental illness, and having one’s loyalties split across countries and cultures. Oscar and Mina have been together for over a decade, but their marriage got off to a bad start six months ago: on their wedding night Mina took an overdose, and Oscar was lucky to find her in time. The novel begins and ends with her contemplating suicide again; in between, Oscar takes her from New York City to England, where he grew up, for a change of scenery and to work on getting his father’s London flats ready to sell. For Mina, an adjunct professor and Classics tutor, it will be labeled a period of research on her monograph about the rare women who survive in Greek and Roman myth. But when work for his father’s Japanese import company takes Oscar back to New York, Mina is free to pursue her fascination with Phoebe, the sister of Oscar’s childhood friend.

Both Oscar and Mina have Asian ancestry and complicated, dysfunctional family histories. For Oscar, his father’s health scare is a wake-up call, reminding him that everything he has taken for granted is fleeting, and Mina’s uncertain mental and reproductive health force him to face the fact that they might never have children. Although I found this less original and compelling than Buchanan’s debut, I felt true sympathy for the central couple. It’s a realistic picture of marriage: you have to keep readjusting your expectations for a relationship the longer you’re together, and your family situation is inevitably going to have an impact on how you envision your future. I also admired the metaphors and the use of color.

The title is, I think, meant to refer to a sort of time outside of time when wishes can come true; in Mina’s case that’s these few months in London. Bisexuality is something you don’t encounter too often in fiction, so I guess that’s reason enough for it to be included here as a part of Mina’s story, though I wouldn’t say it adds much to the narrative. If it had been up to me, instead of birds I would have picked up on the repeated peony images (Mina has them tattooed up her arms, for instance) for the title and cover.

Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping, and Risking It All with the Greatest Chef in the World by Jeff Gordinier

(Coming on July 9th from Tim Duggan Books [USA] and on October 3rd from Icon Books [UK])

Noma, René Redzepi’s restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, has widely been considered the best in the world. In 2013, though, it suffered a fall from grace when some bad mussels led to a norovirus outbreak that affected dozens of customers. Redzepi wanted to shake things up and rebuild Noma’s reputation for culinary innovation, so in the four years that followed he also opened pop-up restaurants in Tulum, Mexico and Sydney, Australia. Journalist Jeff Gordinier, food and drinks editor at Esquire magazine, went along for the ride and reports on the Noma team’s adventures, painting a portrait of a charismatic, driven chef. For foodies and newbies alike, it’s a brisk, delightful tour through world cuisine as well as a shrewd character study. (Full review coming soon to BookBrowse.)

Noma, René Redzepi’s restaurant in Copenhagen, Denmark, has widely been considered the best in the world. In 2013, though, it suffered a fall from grace when some bad mussels led to a norovirus outbreak that affected dozens of customers. Redzepi wanted to shake things up and rebuild Noma’s reputation for culinary innovation, so in the four years that followed he also opened pop-up restaurants in Tulum, Mexico and Sydney, Australia. Journalist Jeff Gordinier, food and drinks editor at Esquire magazine, went along for the ride and reports on the Noma team’s adventures, painting a portrait of a charismatic, driven chef. For foodies and newbies alike, it’s a brisk, delightful tour through world cuisine as well as a shrewd character study. (Full review coming soon to BookBrowse.)

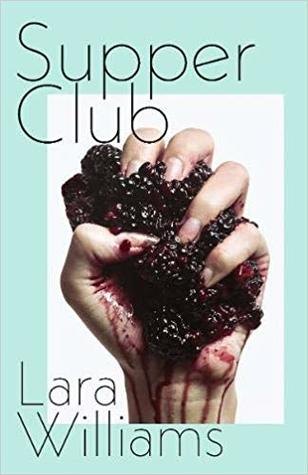

Supper Club by Lara Williams

(Coming on July 9th from G.P. Putnam’s Sons [USA] and July 4th from Hamish Hamilton [UK])

“What could violate social convention more than women coming together to indulge their hunger and take up space?” Roberta and Stevie become instant besties when Stevie is hired as an intern at the fashion website where Roberta has been a writer for four years. Stevie is a would-be artist and Roberta loves to cook; they decide to combine their talents and host Supper Clubs that allow emotionally damaged women to indulge their appetites. The pop-ups take place at down-at-heel or not-strictly-legal locations, the food is foraged from dumpsters, and there are sometimes elaborate themes and costumes. These bacchanalian events tend to devolve into drunkenness, drug-taking, partial nudity and food fights.

The central two-thirds of the book alternates chapters between the present day, when Roberta is 28–30, and her uni days. I don’t think it can be coincidental that Roberta and Stevie are both feminized male names; rather, we are meant to ask to what extent all the characters have defined themselves in terms of the men in their lives. For Roberta, this includes the father who left when she was seven and now thinks he can send her chatty e-mails whenever he wants; the fellow student who raped her at uni; and the philosophy professor she dated for ages even though he treated her like an inconvenient child. Supper Club is performance art, but it’s also about creating personal meaning when family and romance have failed you.

The central two-thirds of the book alternates chapters between the present day, when Roberta is 28–30, and her uni days. I don’t think it can be coincidental that Roberta and Stevie are both feminized male names; rather, we are meant to ask to what extent all the characters have defined themselves in terms of the men in their lives. For Roberta, this includes the father who left when she was seven and now thinks he can send her chatty e-mails whenever he wants; the fellow student who raped her at uni; and the philosophy professor she dated for ages even though he treated her like an inconvenient child. Supper Club is performance art, but it’s also about creating personal meaning when family and romance have failed you.

I was slightly disappointed that Supper Club itself becomes less important as time goes on, and that we never get closure about Roberta’s father. I also found it difficult to keep the secondary characters’ backstories straight. But overall this is a great debut novel with strong themes of female friendship and food. Roberta opens most chapters with cooking lore and tips, and there are some terrific scenes set in cafés. I suspect this will mean a lot to a lot of young women. Particularly if you’ve liked Sweetbitter (Stephanie Danler) and Friendship (Emily Gould), give it a taste.

With thanks to Sapphire Rees of Penguin for the proof copy for review.

I only found four stand-outs here. “Reasonable Terms” is a playful piece of magic realism in which a zoo’s giraffes get the gorilla to write out a list of demands for their keepers and, when agreement isn’t forthcoming, stage a mass mock suicide. In “How to Revitalize the Snake in Your Life,” a woman takes revenge on her boa constrictor-keeping boyfriend. In “Miss Waldron’s Red Colobus,” which reminded me of Ned Beauman’s madcap style, a boarding school teenager eludes the private detectives her parents have hired to keep tabs on her and makes it all the way to Ghana, where a new species of monkey is named after her. My favorite of all was “Preservation,” in which Mary saves wildlife paintings through her work as an art conservator but can’t save her father from terminal illness.

I only found four stand-outs here. “Reasonable Terms” is a playful piece of magic realism in which a zoo’s giraffes get the gorilla to write out a list of demands for their keepers and, when agreement isn’t forthcoming, stage a mass mock suicide. In “How to Revitalize the Snake in Your Life,” a woman takes revenge on her boa constrictor-keeping boyfriend. In “Miss Waldron’s Red Colobus,” which reminded me of Ned Beauman’s madcap style, a boarding school teenager eludes the private detectives her parents have hired to keep tabs on her and makes it all the way to Ghana, where a new species of monkey is named after her. My favorite of all was “Preservation,” in which Mary saves wildlife paintings through her work as an art conservator but can’t save her father from terminal illness.  The first half of the book reports Manuel’s life in the third person, while the second is in the first person, narrated by his son, Antonio. Through that shift in perspective we come to see Manuel as both a comic and a tragic figure: he insists on speaking English, but his grammar and accent are atrocious; he cultivates proud Canadian traditions, like playing the anthem on repeat on Canada Day and spending Christmas Eve at Niagara Falls, but he’s also a drunk the neighborhood children laugh at. Although the two chapters set back in Portugal were my favorites, Manuel is a compelling, sympathetic character throughout, and I appreciated De Sa’s picture of the immigrant’s contrasting feelings of home and community. Particularly recommended if you’ve enjoyed That Time I Loved You by Carrianne Leung.

The first half of the book reports Manuel’s life in the third person, while the second is in the first person, narrated by his son, Antonio. Through that shift in perspective we come to see Manuel as both a comic and a tragic figure: he insists on speaking English, but his grammar and accent are atrocious; he cultivates proud Canadian traditions, like playing the anthem on repeat on Canada Day and spending Christmas Eve at Niagara Falls, but he’s also a drunk the neighborhood children laugh at. Although the two chapters set back in Portugal were my favorites, Manuel is a compelling, sympathetic character throughout, and I appreciated De Sa’s picture of the immigrant’s contrasting feelings of home and community. Particularly recommended if you’ve enjoyed That Time I Loved You by Carrianne Leung.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness.

A mudslide blocked the route we should have taken back from Milan to Paris, so we rebooked onto trains via Switzerland. This plus the sub-Alpine setting for our next-to-last day made the perfect context for racing through Where the Hornbeam Grows: A Journey in Search of a Garden by Beth Lynch in just two days. Lynch moved from England to Switzerland when her husband took a job in Zurich. Suddenly she had to navigate daily life, including frosty locals and convoluted bureaucracy, in a second language. The sense of displacement was exacerbated by her lack of access to a garden. Gardening had always been a whole-family passion, and after her parents’ death their Sussex garden was lost to her. Two years later she and her husband moved to a cottage in western Switzerland and cultivated a garden idyll, but it wasn’t enough to neutralize their loneliness. Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.

Confessions of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell: This picks up right where The Diary of a Bookseller left off and carries through the whole of 2015. Again it’s built on the daily routines of buying and selling books, including customers’ and colleagues’ quirks, and of being out and about in a small town. I wished I was in Wigtown instead of Milan! Because of where I was reading the book, I got particular enjoyment out of the characterization of Emanuela (soon known as “Granny” for her poor eyesight and myriad aches and gripes), who comes over from Italy to volunteer in the bookshop for the summer. Bythell’s break-up with “Anna” is a recurring theme in this volume, I suspect because his editor/publisher insisted on an injection of emotional drama.  City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert: There’s a fun, saucy feel to this novel set mostly in 1940s New York City. Twenty-year-old Vivian Morris comes to sew costumes for her Aunt Peg’s rundown theatre and falls in with a disreputable lot of actors and showgirls. When she does something bad enough to get her in the tabloids and jeopardize her future, she retreats in disgrace to her parents’ – but soon the war starts and she’s called back to help with Peg’s lunchtime propaganda shows at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The quirky coming-of-age narrative reminded me a lot of classic John Irving, while the specifics of the setting made me think of Wise Children, All the Beautiful Girls Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.

Judgment Day by Sandra M. Gilbert: English majors will know Gilbert best for her landmark work of criticism, The Madwoman in the Attic (co-written with Susan Gubar). I had no idea that she writes poetry. This latest collection has a lot of interesting reflections on religion, food and art, as well as elegies to those she’s lost. Raised Catholic, Gilbert married a Jew, and the traditions of Judaism still hold meaning for her after husband’s death even though she’s effectively an atheist. “Pompeii and After,” a series of poems describing food scenes in paintings, from da Vinci to Hopper, is particularly memorable.  Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…

Vintage 1954 by Antoine Laurain: Dreadful! I would say: avoid this sappy time-travel novel at all costs. I thought the setup promised a gentle dose of fantasy, and liked the fact that the characters could meet their ancestors and Paris celebrities during their temporary stay in 1954. But the characters are one-dimensional stereotypes, and the plot is far-fetched and silly. I know many others have found this delightful, so consider me in the minority…