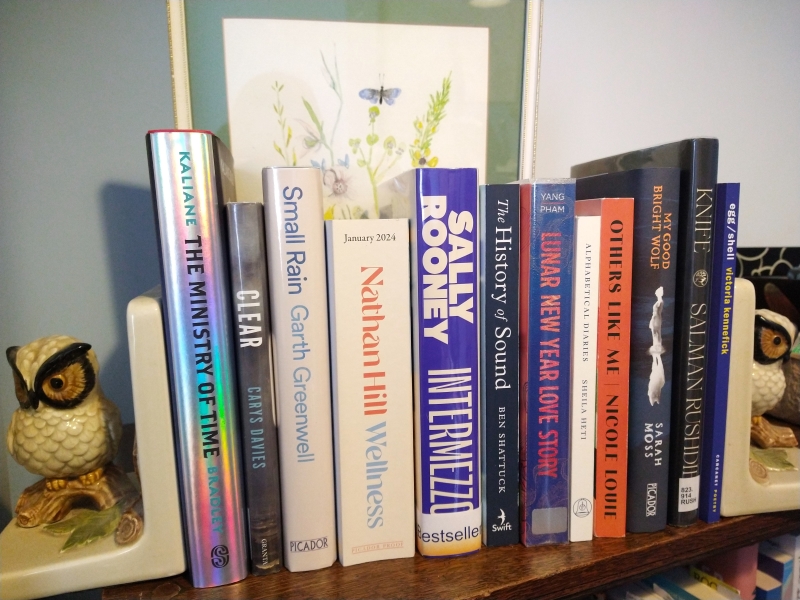

Review Catch-up: Matt Gaw, Sheila Heti, Liz Jensen (and a Pile of DNFs)

Today I have a travel book about appreciating nature in any weather, a sui generis memoir drawn from a decade of diaries, and an impassioned cry for the environment in the wake of a young adult son’s death.

I’m also bidding farewell to a whole slew of review books that have been hanging around, in some cases, for literal years – I think one is from 2021, and several others from 2022. Putting a book on my “set aside” shelf can be a kiss of death … or I can go back at a better time and end up loving it. It’s hard to predict which will occur. On these, alas, I have had to admit defeat and will pass the books on to other homes.

In All Weathers: A Journey through Rain, Fog, Wind, Ice and Everything in Between by Matt Gaw

Gaw’s two previous nature/travel memoirs, the enjoyable The Pull of the River and Under the Stars, involve gentle rambles through British landscapes, along with commentary on history, nature and science. The remit is much the same here. The book is split into four long sections: “Rain,” “Fog,” “Ice and Snow,” and “Wind.” The adventures always start from and end up at the author’s home in Suffolk, but he ranges as far as the Peak District, Cumbria and the Isle of Skye. Wild swimming is one way in which he experiences places. He notices a lot and describes it all in lovely and relatable prose.

I was tickled by the definitions of, and statistics about, a “white Christmas”: in the UK, it counts if there’s even a single snowflake falling, whereas in the US there has to be 2.5 cm or more of standing snow. (Scotland is most likely to experience white Christmases; it has had 37 since 1960 vs. 26 in northern England. The English snow record is 43 cm, at Buxton and Malham Tarn in 1981 and 2009.) There’s underlying mild dread as he notes how weather patterns have changed and will likely continue changing, ever more dramatically, into his children’s future.

I was tickled by the definitions of, and statistics about, a “white Christmas”: in the UK, it counts if there’s even a single snowflake falling, whereas in the US there has to be 2.5 cm or more of standing snow. (Scotland is most likely to experience white Christmases; it has had 37 since 1960 vs. 26 in northern England. The English snow record is 43 cm, at Buxton and Malham Tarn in 1981 and 2009.) There’s underlying mild dread as he notes how weather patterns have changed and will likely continue changing, ever more dramatically, into his children’s future.

I find I don’t have much to say about this book because it is very nice but doesn’t do anything interesting or tackle anything that isn’t familiar from many other nature books (such as Rain by Melissa Harrison and Forecast by Joe Shute). It’s unfortunate for Gaw that his ideas often seem to have been done before – his book on night-walking, in particular, was eclipsed by several other works on that topic that came out at around the same time. I hope that the next time around he’ll get more editorial guidance to pursue original topics. It might take just a little push to get him to the next level where he could compete with top UK nature writers.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson Books for the free copy for review.

Alphabetical Diaries by Sheila Heti

Heti put the contents of ten years of her diaries into a spreadsheet, alphabetizing each sentence (including articles), and then ruthlessly culled the results until she had a 25-chapter (no ‘X’) book. You could hardly call it a narrative, yet looking for one is so hardwired that every few sentences you are jolted out of what feels like a mini-story and into something new. Instead, you might think of it as an autobiographical mosaic. The recurring topics are familiar from the rest of Heti’s oeuvre, with obsessive cogitating about relationships, art and identity. But there are also the practicalities of trying to make a living as a woman in a creative profession. Tendrils of the everyday poke out here and there as she makes a meal, catches a plane, or buys clothes. Men loom large: explicit accounts of sex with Pavel and Lars (though also Fiona); advising her friend Lemons on his love life. There are also meta musings on what she is trying to achieve with her book projects and on what literature can be.

Grammatically, the document is a lot more interesting than it could be – or than a similar experiment based on my diary would be, for instance – because Heti sometimes writes in incomplete sentences, dropping the initial pronoun; or intersperses rhetorical questions or notes to self in the imperative. So, yes, ‘I’ is a long chapter, but not only because of self-absorbed “I…” statements; there’s also plenty of “If…” and “It’s…” ‘H’ and ‘W’ are longer sections than might be expected because of the questioning mode. But it’s at the sentence level that the book makes the biggest impression: lines group together, complement or contradict each other, or flout coherence by being so merrily à propos of nothing. Here are a few passages to give a flavour:

Grammatically, the document is a lot more interesting than it could be – or than a similar experiment based on my diary would be, for instance – because Heti sometimes writes in incomplete sentences, dropping the initial pronoun; or intersperses rhetorical questions or notes to self in the imperative. So, yes, ‘I’ is a long chapter, but not only because of self-absorbed “I…” statements; there’s also plenty of “If…” and “It’s…” ‘H’ and ‘W’ are longer sections than might be expected because of the questioning mode. But it’s at the sentence level that the book makes the biggest impression: lines group together, complement or contradict each other, or flout coherence by being so merrily à propos of nothing. Here are a few passages to give a flavour:

Am I wasting my time? Am low on money. Am making noodles. Am reading Emma. Am tired and will go to sleep. Am tired today and I feel like I may be getting a cold. Ambivalence gives you something to do, something to think about.

Best not to live too emotionally in the future—it hardly ever comes to pass. Better to be on the outside, where you have always been, all your life, even in school, nothing changes. Better to look outward than inward. Blow jobs and tenderness. Books that fall in between the cracks of all aspects of the human endeavour.

It’s 2:34 every time I check the time these days. It’s 4 p.m. It’s 4:41 now. It’s a fantasy of being saved. It’s a stupid idea. It’s a yellow, cloudy sky. It’s amazing to me how life keeps going. It’s better to work, to go into the underground cave where there are books, than to fritter away time online. It’s crazy that I need all of these mental crutches in order to live. It’s fiction. It’s fine.

Scrambled eggs on toast at Yaddo. Second-guessing everything. Second, he said that no one is buying fiction. See the complexity. See the souls. See what kind of story the book can accommodate, if any. Seeing her for coffee was not so bad.

It’s surprising how much sense a text constructed so apparently haphazardly makes, perhaps because of the same subject and style throughout. Sometimes aphoristic, sometimes poetic (all that anaphora), the book is playful but overall serious about the capturing of a life on the page. Heti transcends the quotidian by exploding the one-thing-after-another tedium of chronology. Remarkably, the collage approach produces a more genuine, crystalline vision of the self than precise scenes and cause-and-effect chains ever could. A work of life writing like no other, it must be read in a manner all its own that it teaches you as you go along. I admire it enormously and hope I might write something even half as daring one day.

With thanks to Fitzcarraldo Editions for the free copy for review.

Your Wild and Precious Life: On grief, hope and rebellion by Liz Jensen

Jensen’s younger son, Raphaël Coleman, was just 25 when he collapsed while filming a documentary in South Africa and died of a previously undiagnosed heart condition. Raph had been involved in Extinction Rebellion and Jensen is a founding member of Writers Rebel. They both deemed activism “the best antidote to depression.” Her son had been obsessed with wildlife from a young age and was rewilding acres of their land in France, as well as making environmentalist films (he had achieved minor fame as a child actor in Nanny McPhee) and participating in direct action, such as at the Brazilian embassy in London.

For Jensen, the challenge, especially after lockdown confined her to her Copenhagen flat, was to channel grief into further radicalism rather than retreating into herself or giving in to the lure of suicide. She tried to see personal grief as a reminder of ecogrief, and therefore as a spur. One way that she coped was turning towards the supernatural. She continued to hear and speak to Raph, in daily life as well as through a medium, and interpreted bird sightings as signs of his continued presence. An additional point of interest to me was that the author’s husband is Carsten Jensen, the writer of one of my favourite books, We, the Drowned.

For Jensen, the challenge, especially after lockdown confined her to her Copenhagen flat, was to channel grief into further radicalism rather than retreating into herself or giving in to the lure of suicide. She tried to see personal grief as a reminder of ecogrief, and therefore as a spur. One way that she coped was turning towards the supernatural. She continued to hear and speak to Raph, in daily life as well as through a medium, and interpreted bird sightings as signs of his continued presence. An additional point of interest to me was that the author’s husband is Carsten Jensen, the writer of one of my favourite books, We, the Drowned.

This doesn’t particularly stand out among the dozens of bereavement memoirs I’ve read. (It was also remarkably similar to Alexandra Fuller’s Fi, which I’d read not long before.) Perhaps more years of reflection would have helped – Mary Karr advises seven – though I suspect Jensen felt, quite rightly, that given the current state of the environment we have no time to waste. And I have no doubt that the combination of a mother’s love and an ecological conscience will make this book meaningful to many readers.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

And the DNFs…

there are more things, Yara Rodrigues Fowler – I loved Stubborn Archivist so much that I leapt at the chance to read her follow-up, but it was just too dull and involved about Brazilian versus UK politics. Nor did the stylistic tricks feel as novel this time around. I read 66 pages. (Fleet)

The Rabbit Hutch, Tess Gunty – Gunty dazzled critics and prize judges in the USA, winning a National Book Award. I was drawn to her debut novel for the composite picture of the residents of one Indiana apartment building and the strange connections that develop between them over one summer week, including perhaps a murder? Blandine, the central character, is a sort of modern-day mystic but hard to warm to (“She normally tries to avoid saying in which out loud, to minimize the number of people who find her insufferable”), as are all the characters. This felt like try-hard MFA writing. I read 85 pages. (Oneworld)

Eve: The Disobedient Future of Birth, Claire Horn – I usually get on well with Wellcome Collection books. I think the problem here was that there was too much material that was familiar to me from having read Womb by Leah Hazard – even the SF-geared stuff about artificial wombs. I read 45 pages. (Profile Books)

Blessings, Chukwuebuka Ibeh – This debut novel has a confident voice, buttressed by determination to reveal what life is like for queer people living in countries where homosexuality is criminalized. Obiefuna is cast out for having a crush on Aboy, his father’s apprentice, even though the two young men share nothing more physical than a significant gaze into each other’s eyes. The strict boarding school his father sends him to is a place of privation, hierarchy, hazing and, I suspect, same-sex experimentation. I found the writing capable but couldn’t get past a sense of dread about what was going to happen. Meanwhile, I didn’t think the alternating chapters from Obiefuna’s mother’s perspective added anything to the narrative. I read 62 pages. (Penguin Viking)

The War for Gloria, Atticus Lish – Lish’s debut novel, Preparation for the Next Life, was excellent, but I could never get stuck in to this follow-up, despite the appealing medical theme. When Gloria Goltz is diagnosed with ALS, her 15-year-old son Corey turns to his absent father and others for support. It was also unfortunate that Lish mentions the Ice Bucket Challenge: that was popularized in 2014, whereas the book is set in 2010. I read 75 pages. (Serpent’s Tail)

Snow Widows: Scott’s Fatal Antarctic Expedition through the Eyes of the Women They Left Behind, Katherine MacInnes – I seriously overestimated my interest in polar exploration narratives. MacInnes seems to have done quite a good job of creating novelistic scenes through research, though. I read 35 pages. (William Collins)

The Woodcock, Richard Smyth – I feel particularly bad about this one as I’ve read and enjoyed three of Smyth’s nature books and my husband and I are friendly with him on Twitter. Initially, I got Thomas Hardy, D.H. Lawrence and Sarah Perry (The Essex Serpent, anyway) vibes from this 1920s-set novel about the upheaval a naturalist and his wife experience when an American whaler and his daughters arrive in their small coastal English town. I read 90 pages. (Fairlight Books)

Better Broken than New: A Fragmented Memoir, Lisa St Aubin de Terán – I accepted this for review because I’d often seen the author’s name on spines in secondhand bookstores but didn’t know anything about her work. The précis of her globe-trotting life is stranger than fiction: marriage to a Venezuelan freedom fighter, managing a sugar plantation in the Andes, living in an Italian palace for 20 years, founding a charity in Mozambique. The vignettes in the early part of the book (e.g., skipping school and going on daytrips by train at age eight) are entertaining, if written with blithe disregard for a reader’s need for context or perspective. But the fragmented nature means it all feels as random as life, without the necessary authorial shaping. The publisher has done her a disservice as she seeks to relaunch her career by not proofreading properly: Many small errors slipped through the net, making this look like a sloppy manuscript. The worst happen to be other authors’ names: Jane ‘Austin’, ‘Kahil’ Gibran, Virginia ‘Wolfe’. Are you kidding me?! I read 53 pages. (Amaurea Press)

#NonFicNov: Being the Expert on Covid Diaries

This year the Be/Ask/Become the Expert week of the month-long Nonfiction November challenge is hosted by Veronica of The Thousand Book Project. (In previous years I’ve contributed lists of women’s religious memoirs (twice), accounts of postpartum depression, and books on “care”.)

I’ve been devouring nonfiction responses to COVID-19 for over a year now. Even memoirs that are not specifically structured as diaries take pains to give a sense of what life was like from day to day during the early months of the pandemic, including the fear of infection and the experience of lockdown. Covid is mentioned in lots of new releases these days, fiction or nonfiction, even if just via an introduction or epilogue, but I’ve focused on books where it’s a major element. At the end of the post I list others I’ve read on the theme, but first I feature four recent releases that I was sent for review.

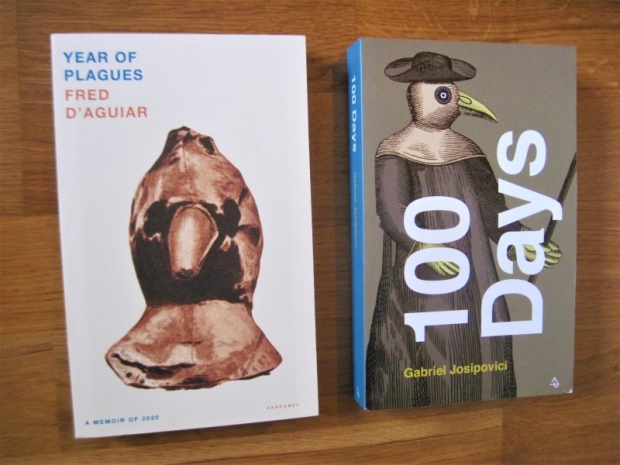

Year of Plagues: A Memoir of 2020 by Fred D’Aguiar

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

The plague for D’Aguiar was dual: not just Covid, but cancer. Specifically, stage 4 prostate cancer. A hospital was the last place he wanted to spend time during a pandemic, yet his treatment required frequent visits. Current events, including a curfew in his adopted home of Los Angeles and the protests following George Floyd’s murder, form a distant background to an allegorized medical struggle. D’Aguiar personifies his illness as a force intent on harming him; his hope is that he can be like Anansi and outwit the Brer Rabbit of cancer. He imagines dialogues between himself and his illness as they spar through a turbulent year.

Cancer needs a song: tambourine and cymbals and a choir, not to raise it from the dead but [to] lay it to rest finally.

Tracing the effects of his cancer on his wife and children as well as on his own body, he wonders if the treatment will disrupt his sense of his own masculinity. I thought the narrative would hit home given that I have a family member going through the same thing, but it struck me as a jumble, full of repetition and TMI moments. Expecting concision from a poet, I wanted the highlights reel instead of 323 rambling pages.

(Carcanet Press, August 26.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

100 Days by Gabriel Josipovici

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Beginning in March 2020, Josipovici challenged himself to write a diary entry and mini-essay each day for 100 days – which happened to correspond almost exactly to the length of the UK’s first lockdown. Approaching age 80, he felt the virus had offered “the unexpected gift of a bracket round life” that he “mustn’t fritter away.” He chose an alphabetical framework, stretching from Aachen to Zoos and covering everything from his upbringing in Egypt to his love of walking in the Sussex Downs. I had the feeling that I should have read some of his fiction first so that I could spot how his ideas and experiences had infiltrated it; I’m now rectifying this by reading his novella The Cemetery in Barnes, in which I recognize a late-life remarriage and London versus countryside settings.

Still, I appreciated Josipovici’s thoughts on literature and his own aims for his work (more so than the rehashing of Covid statistics and official briefings from Boris Johnson et al., almost unbearable to encounter again):

In my writing I have always eschewed visual descriptions, perhaps because I don’t have a strong visual memory myself, but actually it is because reading such descriptions in other people’s novels I am instantly bored and feel it is so much dead wood.

nearly all my books and stories try to force the reader (and, I suppose, as I wrote, to force me) to face the strange phenomenon that everything does indeed pass, and that one day, perhaps sooner than most people think, humanity will pass and, eventually, the universe, but that most of the time we live as though all was permanent, including ourselves. What rich soil for the artist!

Why have I always had such an aversion to first person narratives? I think precisely because of their dishonesty – they start from a falsehood and can never recover. The falsehood that ‘I’ can talk in such detail and so smoothly about what has ‘happened’ to ‘me’, or even, sometimes, what is actually happening as ‘I’ write.

You never know till you’ve plunged in just what it is you really want to write. When I started writing The Inventory I had no idea repetition would play such an important role in it. And so it has been all through, right up to The Cemetery in Barnes. If I was a poet I would no doubt use refrains – I love the way the same thing becomes different the second time round

To write a novel in which nothing happens and yet everything happens: a secret dream of mine ever since I began to write

I did sense some misogyny, though, as it’s generally female writers he singles out for criticism: Iris Murdoch is his prime example of the overuse of adjectives and adverbs, he mentions a “dreadful novel” he’s reading by Elizabeth Bowen, and he describes Jean Rhys and Dorothy Whipple as women “who, raised on a diet of the classic English novel, howled with anguish when life did not, for them, turn out as they felt it should.”

While this was enjoyable to flip through, it’s probably more for existing fans than for readers new to the author’s work, and the Covid connection isn’t integral to the writing experiment.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

A stanza from the below collection to link the first two books to this next one:

Have they found him yet, I wonder,

whoever it is strolling

about as a plague doctor, outlandish

beak and all?

The Crash Wake and Other Poems by Owen Lowery

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

Lowery was a tetraplegic poet – wheelchair-bound and on a ventilator – who also survived a serious car crash in February 2020 before his death in May 2021. It’s astonishing how much his body withstood, leaving his mind not just intact but capable of generating dozens of seemingly effortless poems. Most of the first half of this posthumous collection, his third overall, is taken up by a long, multipart poem entitled “The Crash Wake” (it’s composed of 104 12-line poems, to be precise), in which his complicated recovery gets bound up with wider anxiety about the pandemic: “It will take time and / more to find our way / back to who we were before the shimmer / and promise of our snapped day.”

As the seventh anniversary of his wedding to Jayne nears, Lowery reflects on how love has kept him going despite flashbacks to the accident and feeling written off by his doctors. In the second section of the book, the subjects vary from the arts (Paula Rego’s photographs, Stanley Spencer’s paintings, R.S. Thomas’s theology) to sport. There is also a lovely “Remembrance Day Sequence” imagining what various soldiers, including Edward Thomas and his own grandfather, lived through. The final piece is a prose horror story about a magpie. Like a magpie, I found many sparkly gems in this wide-ranging collection.

(Carcanet Press, October 28.) With thanks to the publisher for the free e-copy for review.

Behind the Mask: Living Alone in the Epicenter by Kate Walter

[135 pages, so I’m counting this one towards #NovNov, too]

For Walter, a freelance journalist and longtime Manhattan resident, coronavirus turned life upside down. Retired from college teaching and living in Westbeth Artists Housing, she’d relied on activities outside the home for socializing. To a single extrovert, lockdown offered no benefits; she spent holidays alone instead of with her large Irish Catholic family. Even one of the world’s great cities could be a site of boredom and isolation. Still, she gamely moved her hobbies onto Zoom as much as possible, and welcomed an escape to Jersey Shore.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

In short essays, she proceeds month by month through the pandemic: what changed, what kept her sane, and what she was missing. Walter considers herself a “gay elder” and was particularly sad the Pride March didn’t go ahead in 2020. She also found herself ‘coming out again’, at age 71, when she was asked by her alma mater to encapsulate the 50 years since graduation in 100 words.

There’s a lot here to relate to – being glued to the news, anxiety over Trump’s possible re-election, looking forward to vaccination appointments – and the book is also revealing on the special challenges for older people and those who don’t live with family. However, I found the whole fairly repetitive (perhaps as a result of some pieces originally appearing in The Village Sun and then being tweaked and inserted here).

Before an appendix of four short pre-Covid essays, there’s a section of pandemic writing prompts: 12 sets of questions to use to think through the last year and a half and what it’s meant. E.g. “Did living through this extraordinary experience change your outlook on life?” If you’ve been meaning to leave a written record of this time for posterity, this list would be a great place to start.

(Heliotrope Books, November 16.) With thanks to the publicist for the free e-copy for review.

Other Covid-themed nonfiction I have read:

Medical accounts

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

Breathtaking by Rachel Clarke

- Intensive Care by Gavin Francis

- Every Minute Is a Day by Robert Meyer and Dan Koeppel (reviewed for Shelf Awareness)

- Duty of Care by Dominic Pimenta

- Many Different Kinds of Love by Michael Rosen

+ I have a proof copy of Everything Is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Time of Pandemic by Roopa Farooki, coming out in January.

Nature writing

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

Goshawk Summer by James Aldred

- The Heeding by Rob Cowen (in poetry form)

- Birdsong in a Time of Silence by Steven Lovatt

- The Consolation of Nature by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren

- Skylarks with Rosie by Stephen Moss

General responses

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

Hold Still (a National Portrait Gallery commission of 100 photographs taken in the UK in 2020)

- The Rome Plague Diaries by Matthew Kneale

- Quarantine Comix by Rachael Smith (in graphic novel form; reviewed for Foreword Reviews)

- UnPresidented by Jon Sopel

+ on my Kindle: Alone Together, an anthology of personal essays

+ on my TBR: What Just Happened: Notes on a Long Year by Charles Finch

If you read just one… Make it Intensive Care by Gavin Francis. (And, if you love nature books, follow that up with The Consolation of Nature.)

Can you see yourself reading any of these?

Doorstopper of the Month: Theft by Finding by David Sedaris

I’ve read six of David Sedaris’s humorous collections of personal essays. A college friend first recommended him to me in 2011, and I started with When You Are Engulfed in Flames – which I still think is his best book, though Me Talk Pretty One Day is also very good. Sedaris can be riotously funny, and witty and bittersweet the rest of the time. From Raleigh, North Carolina, he has lived in New York, London, Paris, Normandy and Tokyo. Many of his essays stem from minor incidents in his travels. His kooky Greek-American family members and longsuffering partner, Hugh Hamrick, are his stock characters, and his pieces delight in cultural and linguistic misunderstandings and human obstinacy versus openheartedness.

When I heard Sedaris was publishing his selected diaries, I wasn’t sure I’d read them. I knew many of his essays grow out of episodes recorded in the diary, so would the entries end up seeming redundant? I’d pretty much convinced myself that I was going to give Theft by Finding a miss – until I won a proof copy in a Goodreads giveaway. This is the first volume, covering 1977 to 2002; a second volume from 2003 onwards is planned.

What I most liked about this book is the sense you get of the sweep of the author’s life: from living in his North Carolina hometown and doing odd construction jobs, hitchhiking and taking drugs to producing plays, going on book tours and jetting between Paris and New York City, via an interlude in Chicago (where he attended art school and taught writing). Major world events occasionally make it in – the Three Mile Island disaster, Princess Diana’s death, the Bush/Gore election, 9/11 – but for the most part this is about daily nonevents. It’s a bit of a shock to come across a serious moment, like his mother’s sudden death in 1991.

What I most liked about this book is the sense you get of the sweep of the author’s life: from living in his North Carolina hometown and doing odd construction jobs, hitchhiking and taking drugs to producing plays, going on book tours and jetting between Paris and New York City, via an interlude in Chicago (where he attended art school and taught writing). Major world events occasionally make it in – the Three Mile Island disaster, Princess Diana’s death, the Bush/Gore election, 9/11 – but for the most part this is about daily nonevents. It’s a bit of a shock to come across a serious moment, like his mother’s sudden death in 1991.

One thing that remains constant is Sedaris’s fascination with people’s quirks. For instance, nearly every night for nine years he visited his local IHOP for coffee, cigarettes and people-watching. He seems to meet an inordinately large number of homeless, hard-up and crazy types; perhaps, thanks to his own years-long penury (October 6, 1981: “I’ve paid my rent and my phone bill, leaving me with 43 cents”) and addictions (he didn’t quit alcohol and marijuana until 1999), he feels a certain connection with down-and-outs.

By the last few years of the diary, though, he’s having dinners with Mavis Gallant, Susan Sontag, and Merchant & Ivory. This isn’t obnoxious name-dropping, though; I appreciated how Sedaris maintains a kind of bemused surprise about his success rather than developing a feeling of entitlement. He acts almost guilty about his wealth and multiple properties (“I’ve fallen deeper into the luxury pit”). Time spent abroad keeps him humble about his linguistic abilities and gives him a healthy measure of doubt about the American lifestyle; I especially liked his reaction to a Missouri Walmart.

The problem with the book, though, is that the early entries are really quite dull. Things picked up a bit by the early 1980s, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s that I realized I was actually finding the entries laugh-out-loud funny like I expect from Sedaris. The book as a whole is too long and inclusive; Simon Cowell would surely call it indulgent. I tried to imagine what would have resulted if an outsider had reduced the complete diaries to a one-volume selection. A cast list and photographs of Sedaris and his family over the years would also be helpful; I’d be interested to know if any supplementary material was added to the final product that did not appear in my proof.

Ultimately I think this is only for the most die-hard of Sedaris fans. I will certainly read the second volume as I expect it to be funnier and better written overall. But if – as appears to be the case from the marketing slogans in my proof – the publishers are hoping this will introduce Sedaris to new readers, I think they’ll be let down. If you’ve not encountered him before, I suggest picking up Me Talk Pretty One Day or trying one of his radio programs.

Some favorite passages:

October 26, 1985; Chicago: In the park I bought dope. There was a bench nearby, so I sat down for a while and took in the perfect fall day. Then I came home and carved the word failure into a pumpkin.

October 5, 1992; New York: The new Pakistani cashier at the Grand Union is named Dollop.

October 5, 1997; New York: Making it worse, I had to sit through another endless preview for Titanic. Who do they think is going to see that movie?

June 18, 1999; Paris: Today I saw a one-armed dwarf carrying a skateboard. It’s been ninety days since I’ve had a drink.

October 3, 1999; Paris: I said to the clerk, in French, “Hello. Sometimes my clothes are wrinkled. I bought a machine anti-wrinkle, and now I search a table. Have you such a table?” The fellow said, “An ironing board?” “Exactly!”

My rating:

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep.

Urwin is a charming guide to a year in the life of her working farm in Northumberland. Just don’t make the mistake of dismissing her as “the farmer’s wife.” She may only be 4 foot 10 (her Twitter handle is @pintsizedfarmer and her biography describes her as “(probably) the shortest farmer in England”), but her struggles to find attractive waterproofs don’t stop her from putting in hard labor to tend to the daily needs of a 200-strong flock of sheep. First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)

First published in 1991, The Sheep Stell taps into a widespread feeling that we have become cut off from the natural world and that existing in communion with animals is a healthier lifestyle. White’s pleasantly nostalgic memoir tells of finding contentment in the countryside, first on her own and later with a dearly loved family. It is both an evocative picture of a life adapted to seasonal rhythms and an arresting account of the casual sexism – and even violence – White experienced in a traditionally male vocation when she emigrated to New Zealand in 1953. From solitary youthful adventures that recall Gerald Durrell’s and Patrick Leigh Fermor’s to a more settled domestic life with animals reminiscent of the writings of James Herriot and Doreen Tovey, White’s story is unfailingly enjoyable. (I reviewed it for the Times Literary Supplement last year.)  Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.

Axel Lindén left his hipster Stockholm existence behind to take on his parents’ rural collective. On Sheep documents two years in his life as a shepherd aspiring to self-sufficiency and a small-scale model of food production. The diary entries range from a couple of words (“Silage; wet”) to several pages, and tend to cluster around busy times on the farm. The author expresses genuine concern for the sheep’s wellbeing. However, he cannily avoids anthropomorphism, insisting that his loyalty must be to the whole flock rather than to individual animals. The brevity and selectiveness of the diary keep the everyday tasks from becoming tiresome. Instead, the rural routines are comforting, even humbling.  #4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks

#4: The Shepherd’s Life by James Rebanks DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

DNF after 53 pages. I was offered a proof copy by the publisher on Twitter. I thought it would be interesting to hear about a female Icelandic shepherd who was a model before taking over her family farm and then reluctantly went into politics to try to block a hydroelectric power station on her land. Unfortunately, though, the book is scattered and barely competently written. It doesn’t help that the proof is error-strewn. [This mini-review has been corrected to reflect the fact that, unlike what is printed on the proof copy, the sole author is Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, who has written the book as if from Heiða Ásgeirsdóttir’s perspective.]

No One Tells You This: A Memoir by Glynnis MacNicol [July 10, Simon & Schuster]: “If the story doesn’t end with marriage or a child, what then? This question plagued Glynnis MacNicol on the eve of her 40th birthday. … Over the course of her fortieth year, which this memoir chronicles, Glynnis embarks on a revealing journey of self-discovery that continually contradicts everything she’d been led to expect.” (NetGalley download)

No One Tells You This: A Memoir by Glynnis MacNicol [July 10, Simon & Schuster]: “If the story doesn’t end with marriage or a child, what then? This question plagued Glynnis MacNicol on the eve of her 40th birthday. … Over the course of her fortieth year, which this memoir chronicles, Glynnis embarks on a revealing journey of self-discovery that continually contradicts everything she’d been led to expect.” (NetGalley download) The Lost Chapters: Finding Recovery and Renewal One Book at a Time by Leslie Schwartz [July 10, Blue Rider Press]: “Leslie Schwartz’s powerful, skillfully woven memoir of redemption and reading, as told through the list of books she read as she served a 90-day jail sentence. … Incarceration might have ruined her, if not for the stories that comforted her while she was locked up.”

The Lost Chapters: Finding Recovery and Renewal One Book at a Time by Leslie Schwartz [July 10, Blue Rider Press]: “Leslie Schwartz’s powerful, skillfully woven memoir of redemption and reading, as told through the list of books she read as she served a 90-day jail sentence. … Incarceration might have ruined her, if not for the stories that comforted her while she was locked up.” The Bumblebee Flies Anyway: Gardening and Surviving Against the Odds by Kate Bradbury [July 17, Bloomsbury Wildlife]: “Finding herself in a new home in Brighton, Kate Bradbury sets about transforming her decked, barren backyard into a beautiful wildlife garden. She documents the unbuttoning of the earth and the rebirth of the garden, the rewilding of a tiny urban space.”

The Bumblebee Flies Anyway: Gardening and Surviving Against the Odds by Kate Bradbury [July 17, Bloomsbury Wildlife]: “Finding herself in a new home in Brighton, Kate Bradbury sets about transforming her decked, barren backyard into a beautiful wildlife garden. She documents the unbuttoning of the earth and the rebirth of the garden, the rewilding of a tiny urban space.” Crux: A Cross-Border Memoir by Jean Guerrero [July 17, One World]: “A daughter’s quest to find, understand, and save her charismatic, troubled, and elusive father, a self-mythologizing Mexican immigrant who travels across continents—and across the borders between imagination and reality; and spirituality and insanity—fleeing real and invented persecutors.”

Crux: A Cross-Border Memoir by Jean Guerrero [July 17, One World]: “A daughter’s quest to find, understand, and save her charismatic, troubled, and elusive father, a self-mythologizing Mexican immigrant who travels across continents—and across the borders between imagination and reality; and spirituality and insanity—fleeing real and invented persecutors.” The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwon [July 31, Riverhead]: “A shocking novel of violence, love, faith, and loss, as a young woman at an elite American university is drawn into acts of domestic terrorism by a cult tied to North Korea. … The Incendiaries is a fractured love story and a brilliant examination of the minds of extremist terrorists, and of what can happen to people who lose what they love most.” (Print ARC for blog review at UK release on Sept. 6 [Virago])

The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwon [July 31, Riverhead]: “A shocking novel of violence, love, faith, and loss, as a young woman at an elite American university is drawn into acts of domestic terrorism by a cult tied to North Korea. … The Incendiaries is a fractured love story and a brilliant examination of the minds of extremist terrorists, and of what can happen to people who lose what they love most.” (Print ARC for blog review at UK release on Sept. 6 [Virago]) Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller [Aug. 2, Penguin Fig Tree]: I’ve loved Fuller’s two previous novels. This one is described as “a suspenseful story about deception, sexual obsession and atonement” set in 1969 in a run-down English country house. I don’t need to know any more than that; I have no doubt it’ll be brilliant in an Iris Murdoch/Gothic way. (Print ARC for blog review on release date)

Bitter Orange by Claire Fuller [Aug. 2, Penguin Fig Tree]: I’ve loved Fuller’s two previous novels. This one is described as “a suspenseful story about deception, sexual obsession and atonement” set in 1969 in a run-down English country house. I don’t need to know any more than that; I have no doubt it’ll be brilliant in an Iris Murdoch/Gothic way. (Print ARC for blog review on release date) If You Leave Me by Crystal Hana Kim [Aug. 7, William Morrow]: “An emotionally riveting debut novel about war, family, and forbidden love—the unforgettable saga of two ill-fated lovers in Korea and the heartbreaking choices they’re forced to make in the years surrounding the civil war that continues to haunt us today.” This year’s answer to

If You Leave Me by Crystal Hana Kim [Aug. 7, William Morrow]: “An emotionally riveting debut novel about war, family, and forbidden love—the unforgettable saga of two ill-fated lovers in Korea and the heartbreaking choices they’re forced to make in the years surrounding the civil war that continues to haunt us today.” This year’s answer to  A River of Stars by Vanessa Hua [Aug. 14, Ballantine Books]: “In a powerful debut novel about motherhood, immigration, and identity, a pregnant Chinese woman makes her way to California and stakes a claim to the American dream. … an entertaining, wildly unpredictable adventure, told with empathy and wit” Sounds like

A River of Stars by Vanessa Hua [Aug. 14, Ballantine Books]: “In a powerful debut novel about motherhood, immigration, and identity, a pregnant Chinese woman makes her way to California and stakes a claim to the American dream. … an entertaining, wildly unpredictable adventure, told with empathy and wit” Sounds like  The Shakespeare Requirement by Julie Schumacher [Aug. 14, Doubleday]: A sequel to the very funny epistolary novel

The Shakespeare Requirement by Julie Schumacher [Aug. 14, Doubleday]: A sequel to the very funny epistolary novel  Gross Anatomy: Dispatches from the Front (and Back) by Mara Altman [Aug. 21, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “By using a combination of personal anecdotes and fascinating research, Gross Anatomy holds up a magnifying glass to our beliefs, practices, biases, and body parts and shows us the naked truth—that there is greatness in our grossness.” (PDF from publisher; to review for GLAMOUR online)

Gross Anatomy: Dispatches from the Front (and Back) by Mara Altman [Aug. 21, G.P. Putnam’s Sons]: “By using a combination of personal anecdotes and fascinating research, Gross Anatomy holds up a magnifying glass to our beliefs, practices, biases, and body parts and shows us the naked truth—that there is greatness in our grossness.” (PDF from publisher; to review for GLAMOUR online) Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters by Anne Boyd Rioux [Aug. 21, W. W. Norton Company]: This is the bonus one I’ve already read, as part of my research for my Literary Hub article on rereading Little Women at its 150th anniversary. (That’s also the occasion for this charming book.) Rioux unearths Little Women’s origins in Alcott family history, but also traces its influence through to the present day. She also makes a strong feminist case for it. My short Goodreads review is

Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters by Anne Boyd Rioux [Aug. 21, W. W. Norton Company]: This is the bonus one I’ve already read, as part of my research for my Literary Hub article on rereading Little Women at its 150th anniversary. (That’s also the occasion for this charming book.) Rioux unearths Little Women’s origins in Alcott family history, but also traces its influence through to the present day. She also makes a strong feminist case for it. My short Goodreads review is  Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart [Sept. 4, Random House]: I read his memoir but am yet to try his fiction. “When his dream of the perfect marriage, the perfect son, and the perfect life implodes, a Wall Street millionaire takes a cross-country bus trip in search of his college sweetheart and ideals of youth. … [a] biting, brilliant, emotionally resonant novel very much of our times.” (Edelweiss download; for Pittsburgh Post-Gazette review)

Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart [Sept. 4, Random House]: I read his memoir but am yet to try his fiction. “When his dream of the perfect marriage, the perfect son, and the perfect life implodes, a Wall Street millionaire takes a cross-country bus trip in search of his college sweetheart and ideals of youth. … [a] biting, brilliant, emotionally resonant novel very much of our times.” (Edelweiss download; for Pittsburgh Post-Gazette review) In My Mind’s Eye: A Thought Diary by Jan Morris [Sept. 6, Faber & Faber]: One of my most admired writers. “A collection of diary pieces that Jan Morris wrote for the Financial Times over the course of 2017.” I have never before in my life kept a diary of my thoughts, and here at the start of my ninth decade, having for the moment nothing much else to write, I am having a go at it. Good luck to me.

In My Mind’s Eye: A Thought Diary by Jan Morris [Sept. 6, Faber & Faber]: One of my most admired writers. “A collection of diary pieces that Jan Morris wrote for the Financial Times over the course of 2017.” I have never before in my life kept a diary of my thoughts, and here at the start of my ninth decade, having for the moment nothing much else to write, I am having a go at it. Good luck to me. Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power [Sept. 6, Picador]: “[F]or a year she vowed to test a book a month, following its advice to the letter, taking the surest road she knew to a perfect Marianne. As her year-long plan turned into a demented roller coaster where everything she knew was turned upside down, she found herself confronted with a different question: Self-help can change your life, but is it for the better?” (Print ARC)

Help Me!: One Woman’s Quest to Find Out if Self-Help Really Can Change Her Life by Marianne Power [Sept. 6, Picador]: “[F]or a year she vowed to test a book a month, following its advice to the letter, taking the surest road she knew to a perfect Marianne. As her year-long plan turned into a demented roller coaster where everything she knew was turned upside down, she found herself confronted with a different question: Self-help can change your life, but is it for the better?” (Print ARC) Normal People by Sally Rooney [Sept. 6, Faber & Faber]: Much anticipated follow-up to

Normal People by Sally Rooney [Sept. 6, Faber & Faber]: Much anticipated follow-up to  Mrs. Gaskell & Me by Nell Stevens [Sept. 6, Picador]: “In 2013, Nell Stevens is embarking on her PhD … and falling drastically in love with a man who lives in another city. As Nell chases her heart around the world, and as Mrs. Gaskell forms the greatest connection of her life, these two women, though centuries apart, are drawn together.” I was lukewarm on her previous book,

Mrs. Gaskell & Me by Nell Stevens [Sept. 6, Picador]: “In 2013, Nell Stevens is embarking on her PhD … and falling drastically in love with a man who lives in another city. As Nell chases her heart around the world, and as Mrs. Gaskell forms the greatest connection of her life, these two women, though centuries apart, are drawn together.” I was lukewarm on her previous book,  Heart: A History by Sandeep Jauhar [Sept. 18, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: “Deftly alternating between key historical episodes and his own work, Jauhar tells the colorful and little-known story of the doctors who risked their careers and the patients who risked their lives to know and heal our most vital organ. … Affecting, engaging, and beautifully written.” (Edelweiss download)

Heart: A History by Sandeep Jauhar [Sept. 18, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: “Deftly alternating between key historical episodes and his own work, Jauhar tells the colorful and little-known story of the doctors who risked their careers and the patients who risked their lives to know and heal our most vital organ. … Affecting, engaging, and beautifully written.” (Edelweiss download) To the Moon and Back: A Childhood under the Influence by Lisa Kohn [Sept. 18, Heliotrope Books]: “Lisa was raised as a ‘Moonie’—a member of the Unification Church, founded by self-appointed Messiah, Reverend Sun Myung Moon. … Told with spirited candor, [this] reveals how one can leave behind such absurdity and horror and create a life of intention and joy.”

To the Moon and Back: A Childhood under the Influence by Lisa Kohn [Sept. 18, Heliotrope Books]: “Lisa was raised as a ‘Moonie’—a member of the Unification Church, founded by self-appointed Messiah, Reverend Sun Myung Moon. … Told with spirited candor, [this] reveals how one can leave behind such absurdity and horror and create a life of intention and joy.” Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss [Sept. 20, Granta]: I’ve read Moss’s complete (non-academic) oeuvre; I’d read her on any topic. This novella sounds rather similar to her first book, Cold Earth, which I read recently. “Teenage Silvie is living in a remote Northumberland camp as an exercise in experimental archaeology. … Behind and ahead of Silvie’s narrative is the story of a bog girl, a sacrifice, a woman killed by those closest to her, and as the hot summer builds to a terrifying climax, Silvie and the Bog girl are in ever more terrifying proximity.” (NetGalley download)

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss [Sept. 20, Granta]: I’ve read Moss’s complete (non-academic) oeuvre; I’d read her on any topic. This novella sounds rather similar to her first book, Cold Earth, which I read recently. “Teenage Silvie is living in a remote Northumberland camp as an exercise in experimental archaeology. … Behind and ahead of Silvie’s narrative is the story of a bog girl, a sacrifice, a woman killed by those closest to her, and as the hot summer builds to a terrifying climax, Silvie and the Bog girl are in ever more terrifying proximity.” (NetGalley download) Time’s Convert (All Souls Universe #1) by Deborah Harkness [Sept. 25, Viking]: I was a sucker for Harkness’s A Discovery of Witches and its sequels, much to my surprise. (The thinking girl’s Twilight, you see. I don’t otherwise read fantasy.) Set between the American Revolution and contemporary London, this fills in the backstory for some of the vampire characters.

Time’s Convert (All Souls Universe #1) by Deborah Harkness [Sept. 25, Viking]: I was a sucker for Harkness’s A Discovery of Witches and its sequels, much to my surprise. (The thinking girl’s Twilight, you see. I don’t otherwise read fantasy.) Set between the American Revolution and contemporary London, this fills in the backstory for some of the vampire characters. All You Can Ever Know: A Memoir by Nicole Chung [Oct. 2, Catapult]: “Nicole Chung was born severely premature, placed for adoption by her Korean parents, and raised by a white family in a sheltered Oregon town. … With warmth, candor, and startling insight, Chung tells of her search for the people who gave her up, which coincided with the birth of her own child.” (Edelweiss download)

All You Can Ever Know: A Memoir by Nicole Chung [Oct. 2, Catapult]: “Nicole Chung was born severely premature, placed for adoption by her Korean parents, and raised by a white family in a sheltered Oregon town. … With warmth, candor, and startling insight, Chung tells of her search for the people who gave her up, which coincided with the birth of her own child.” (Edelweiss download) Melmoth by Sarah Perry [Oct. 2, Serpent’s Tail]: Gothic fantasy / historical thriller? Not entirely sure. I just know that it’s the follow-up by the author of

Melmoth by Sarah Perry [Oct. 2, Serpent’s Tail]: Gothic fantasy / historical thriller? Not entirely sure. I just know that it’s the follow-up by the author of  The Ravenmaster: Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London by Christopher Skaife [Oct. 2, 4th Estate]: More suitably Gothic pre-Halloween fare! “Legend has it that if the Tower of London’s ravens should perish or be lost, the Crown and kingdom will fall. … [A]fter decades of serving the Queen, Yeoman Warder Christopher Skaife took on the added responsibility of caring for these infamous birds.” I briefly met the author when he accompanied Lindsey Fitzharris to the Wellcome Book Prize ceremony.

The Ravenmaster: Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London by Christopher Skaife [Oct. 2, 4th Estate]: More suitably Gothic pre-Halloween fare! “Legend has it that if the Tower of London’s ravens should perish or be lost, the Crown and kingdom will fall. … [A]fter decades of serving the Queen, Yeoman Warder Christopher Skaife took on the added responsibility of caring for these infamous birds.” I briefly met the author when he accompanied Lindsey Fitzharris to the Wellcome Book Prize ceremony. I Am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche by Sue Prideaux [Oct. 4, Faber & Faber]: “Friedrich Nietzsche’s work forms the bedrock of our contemporary thought, and yet a shroud of misunderstanding surrounds the philosopher behind these proclamations. The time is right for a new take on Nietzsche’s extraordinary life, whose importance as a thinker rivals that of Freud or Marx.” (For a possible TLS review?)

I Am Dynamite!: A Life of Friedrich Nietzsche by Sue Prideaux [Oct. 4, Faber & Faber]: “Friedrich Nietzsche’s work forms the bedrock of our contemporary thought, and yet a shroud of misunderstanding surrounds the philosopher behind these proclamations. The time is right for a new take on Nietzsche’s extraordinary life, whose importance as a thinker rivals that of Freud or Marx.” (For a possible TLS review?) Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott [Oct. 16, Riverhead]: I haven’t been too impressed with Lamott’s recent stuff, but I’ll still read anything she publishes. “In this profound and funny book, Lamott calls for each of us to rediscover the nuggets of hope and wisdom that are buried within us that can make life sweeter than we ever imagined. … Almost Everything pinpoints these moments of insight as it shines an encouraging light forward.”

Almost Everything: Notes on Hope by Anne Lamott [Oct. 16, Riverhead]: I haven’t been too impressed with Lamott’s recent stuff, but I’ll still read anything she publishes. “In this profound and funny book, Lamott calls for each of us to rediscover the nuggets of hope and wisdom that are buried within us that can make life sweeter than we ever imagined. … Almost Everything pinpoints these moments of insight as it shines an encouraging light forward.” The Library Book by Susan Orlean [Oct. 16, Simon & Schuster]: The story of a devastating fire at Los Angeles Public Library in April 1986. “Investigators descended on the scene, but over 30 years later, the mystery remains: Did someone purposefully set fire to the library—and if so, who? Weaving her life-long love of books and reading with the fascinating history of libraries and the sometimes-eccentric characters who run them, … Orlean presents a mesmerizing and uniquely compelling story as only she can.” (Edelweiss download)

The Library Book by Susan Orlean [Oct. 16, Simon & Schuster]: The story of a devastating fire at Los Angeles Public Library in April 1986. “Investigators descended on the scene, but over 30 years later, the mystery remains: Did someone purposefully set fire to the library—and if so, who? Weaving her life-long love of books and reading with the fascinating history of libraries and the sometimes-eccentric characters who run them, … Orlean presents a mesmerizing and uniquely compelling story as only she can.” (Edelweiss download) Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver [Oct. 18, Faber & Faber]: Kingsolver is another author I’d read anything by. “[T]he story of two families, in two centuries, who live at the corner of Sixth and Plum, as they navigate the challenges of surviving a world in the throes of major cultural shifts.” 1880s vs. today, with themes of science and utopianism – I’m excited! (Edelweiss download)

Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver [Oct. 18, Faber & Faber]: Kingsolver is another author I’d read anything by. “[T]he story of two families, in two centuries, who live at the corner of Sixth and Plum, as they navigate the challenges of surviving a world in the throes of major cultural shifts.” 1880s vs. today, with themes of science and utopianism – I’m excited! (Edelweiss download) Nine Pints: A Journey through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood by Rose George [Oct. 23, Metropolitan Books]: “Rose George, author of The Big Necessity [on human waste], is renowned for her intrepid work on topics that are invisible but vitally important. In Nine Pints, she takes us from ancient practices of bloodletting to modern ‘hemovigilance’ teams that track blood-borne diseases.”

Nine Pints: A Journey through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood by Rose George [Oct. 23, Metropolitan Books]: “Rose George, author of The Big Necessity [on human waste], is renowned for her intrepid work on topics that are invisible but vitally important. In Nine Pints, she takes us from ancient practices of bloodletting to modern ‘hemovigilance’ teams that track blood-borne diseases.” The End of the End of the Earth: Essays by Jonathan Franzen [Nov. 13, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: “[G]athers essays and speeches written mostly in the past five years … Whether exploring his complex relationship with his uncle, recounting his young adulthood in New York, or offering an illuminating look at the global seabird crisis, these pieces contain all the wit and disabused realism that we’ve come to expect from Franzen.”

The End of the End of the Earth: Essays by Jonathan Franzen [Nov. 13, Farrar, Straus and Giroux]: “[G]athers essays and speeches written mostly in the past five years … Whether exploring his complex relationship with his uncle, recounting his young adulthood in New York, or offering an illuminating look at the global seabird crisis, these pieces contain all the wit and disabused realism that we’ve come to expect from Franzen.” A River Could Be a Tree by Angela Himsel [Nov. 13, Fig Tree Books]: “How does a woman who grew up in rural Indiana as a fundamentalist Christian end up a practicing Jew in New York? … Ultimately, the connection to God she so relentlessly pursued was found in the most unexpected place: a mikvah on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. This devout Christian Midwesterner found her own form of salvation—as a practicing Jewish woman.”

A River Could Be a Tree by Angela Himsel [Nov. 13, Fig Tree Books]: “How does a woman who grew up in rural Indiana as a fundamentalist Christian end up a practicing Jew in New York? … Ultimately, the connection to God she so relentlessly pursued was found in the most unexpected place: a mikvah on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. This devout Christian Midwesterner found her own form of salvation—as a practicing Jewish woman.” Becoming by Michelle Obama [Nov. 13, Crown]: “In her memoir, a work of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Michelle Obama invites readers into her world, chronicling the experiences that have shaped her—from her childhood on the South Side of Chicago to her years as an executive balancing the demands of motherhood and work, to her time spent at the world’s most famous address.”

Becoming by Michelle Obama [Nov. 13, Crown]: “In her memoir, a work of deep reflection and mesmerizing storytelling, Michelle Obama invites readers into her world, chronicling the experiences that have shaped her—from her childhood on the South Side of Chicago to her years as an executive balancing the demands of motherhood and work, to her time spent at the world’s most famous address.”