#ReadIndies Nonfiction Catch-Up: Ansell, Farrier, Febos, Hoffman, Orlean and Stacey

These are all 2025 releases; for some, it’s approaching a year since I was sent a review copy or read the book. Silly me. At last, I’ve caught up. Reading Indies month, hosted by Kaggsy in memory of her late co-host Lizzy Siddal, is the perfect time to feature books from five independent publishers. I have four works that might broadly be classed as nature writing – though their topics range from birdsong and technology to living in Greece and rewilding a plot in northern Spain – and explorations of celibacy and the writer’s profession.

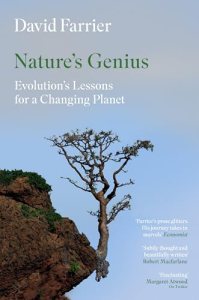

The Edge of Silence: In Search of the Disappearing Sounds of Nature by Neil Ansell

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Ansell draws parallels between his advancing hearing loss and the biodiversity crisis. He puts together a wish list of species – mostly seabirds (divers, grebes), but also inland birds (nightjars) and a couple of non-avian representatives (otters) – that he wants to hear and sets off on public transport adventures to find them. “I must find beauty where I can, and while I still can,” he vows. From his home on the western coast of Scotland near the Highlands, this involves trains or buses that never align with the ferry timetables. Furthest afield for him are two nature reserves in northern England where his mission is to hear bitterns “booming” and natterjack toads croaking at night. There are also mountain excursions to locate ptarmigan, greenshank, and black grouse. His island quarry includes Manx shearwaters (Rum), corncrakes (Coll), puffins (Sanday), and storm petrels (Shetland).

Camping in a tent means cold nights, interrupted sleep, and clouds of midges, but it’s all worth it to have unrepeatable wildlife experiences. He has a very high hit rate for (seeing and) hearing what he intends to, even when they’re just on the verge of what he can decipher with his hearing aids. On the rare occasions when he misses out, he consoles himself with earlier encounters. “I shall settle for the memory, for it feels unimprovable, like a spell that I do not want to break.” I’ve read all of Ansell’s nature memoirs and consider him one of the UK’s top writers on the natural world. His accounts of his low-carbon travels are entertaining, and the tug-of-war between resisting and coming to terms with his disability is heartening. “I have spent this year in defiance of a relentless, unstoppable countdown,” he reflects. What makes this book more universal than niche is the deadline: we and all of these creatures face extinction. Whether it’s sooner or later depends on how we act to address the environmental polycrisis.

With thanks to Birlinn for the free copy for review.

Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet by David Farrier

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

Farrier’s Footprints, which tells the story of the human impact on the Earth, was one of my favourite books of 2020. This contains a similar blend of history, science, and literary points of reference (Farrier is a professor of literature and the environment at the University of Edinburgh), with past changes offering a template for how the future might look different. “We are forcing nature to reimagine itself, and to avert calamity we need to do the same,” he writes. Cliff swallows have evolved blunter wings to better evade cars; captive breeding led foxes to develop the domesticated traits of pet dogs.

It’s not just other species that experience current evolution. Thanks to food abundance and a sedentary lifestyle, humans show a “consumer phenotype,” which superseded the Palaeolithic (95% of human history) and tends toward earlier puberty, autoimmune diseases, and obesity. Farrier also looks at notions of intelligence, language, and time in nature. Sustainable cities will have to cleverly reuse materials. For instance, The Waste House in Brighton is 90% rubbish. (This I have to see!)

There are many interesting nuggets here, and statements that are difficult to argue with, but I struggled to find an overall thread. Cool to see my husband’s old housemate mentioned, though. (Duncan Geere, for collaborating on a hybrid science–art project turning climate data into techno music.)

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

The Dry Season: Finding Pleasure in a Year without Sex by Melissa Febos

Febos considers but rejects the term “sex addiction” for the years in which she had compulsive casual sex (with “the Last Man,” yes, but mostly with women). Since her early teen years, she’d never not been tied to someone. Brief liaisons alternated with long-term relationships: three years with “the Best Ex”; two years that were so emotionally tumultuous that she refers to the woman as “the Maelstrom.” It was the implosion of the latter affair that led to Febos deciding to experiment with celibacy, first for three months, then for a whole year. “I felt feral and sad and couldn’t explain it, but I knew that something had to change.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

The quest involved some research into celibate movements in history, but was largely an internal investigation of her past and psyche. Febos found that she was less attuned to the male gaze. Having worn high heels almost daily for 20 years, she discovered she’s more of a trainers person. Although she was still tempted to flirt with attractive women, e.g. on an airplane, she consciously resisted the impulse to spin random meetings into one-night stands. (A therapist had stopped her short with the blunt observation, “you use people.”) With a new focus on the life of the mind, she insists, “My life was empty of lovers and more full than it had ever been.” (This reminded me of Audre Lorde’s writing on the erotic.) As Silvana Panciera, an Italian scholar on the beguines (a secular nun-like sisterhood), told her: “When you don’t belong to anyone, you belong to everyone. You feel able to love without limits.”

Intriguing that this is all a retrospective, reflecting on her thirties; Febos is now in her mid-forties and married to a woman (poet Donika Kelly). Clearly she felt that it was an important enough year – with landmark epiphanies that changed her and have the potential to help others – to form the basis for a book. For me, she didn’t have much new to offer about celibacy, though it was interesting to read about the topic from an areligious perspective. But I admire the depth of her self-knowledge, and particularly her ability to recreate her mindset at different times. This is another one, like her Girlhood, to keep on the shelf as a model.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

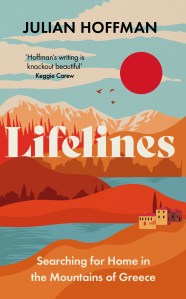

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

Hoffman’s Irreplaceable was my nonfiction book of 2019. Whereas that was a work with a global environmentalist perspective, Lifelines is more personal in scope. It tracks the author’s unexpected route from Canada via the UK to Prespa, a remote area of northern Greece that’s at the crossroads with Albania and North Macedonia. He and his wife, Julia, encountered Prespa in a book and, longing for respite from the breakneck pace of life in London, moved there in 2000. “Like the rivers that spill into these shared lakes, lifelines rarely flow straight. Instead, they contain bends, meanders and loops; they hold, at times, turns of extraordinary surprise.” Birdwatching, which Hoffman suggests is as “a way of cultivating attention,” had been their gateway into a love for nature developed over the next quarter-century and more, and in Greece they delighted in seeing great white and Dalmatian pelicans (which feature on the splendid U.S. cover. It would be lovely to have an illustrated edition of this.)

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

One strand of this warm and fluent memoir is about making a home in Greece: buying and renovating a semi-derelict property, experiencing xenophobia and hospitality from different quarters, and finding a sense of belonging. They’re happy to share their home with nesting wrens, who recur across the book and connect to the tagline of “a story of shelter shared.” In probing the history of his adopted country, Hoffman comes to realise the false, arbitrary nature of borders – wildlife such as brown bears and wolves pay these no heed. Everything is connected and questions of justice are always intersectional. The Covid pandemic and avian influenza (which devastated the region’s pelicans) are setbacks that Hoffman addresses honestly. But the lingering message is a valuable one of bridging divisions and learning how to live in harmony with other people – and with other species.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Joyride by Susan Orlean

As a long-time staff writer for The New Yorker, Orlean has had the good fortune to be able to follow her curiosity wherever it leads, chasing the subjects that interest her and drawing readers in with her infectious enthusiasm. She grew up in suburban Ohio, attended college in Michigan, and lived in Portland, Oregon and Boston before moving to New York City. Her trajectory was from local and alternative papers to the most enviable of national magazines: Esquire, Rolling Stone and Vogue. Orlean gives behind-the-scenes information on lots of her early stories, some of which are reprinted in an appendix. “If you’re truly open, it’s easy to fall in love with your subject,” she writes; maintaining objectivity could be difficult, as when she profiled an Indian spiritual leader with a cult following; and fended off an interviewee’s attachment when she went on the road with a Black gospel choir.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

Her personal life takes a backseat to her career, though she is frank about the breakdown of her first marriage, her second chance at love and late motherhood, and a surprise bout with lung cancer. The chronological approach proceeds book by book, delving into her inspirations, research process and publication journeys. Her first book was about Saturday night as experienced across America. It was a more innocent time, when subjects were more trusting. Orlean and her second husband had farms in the Hudson Valley of New York and in greater Los Angeles, and she ended up writing a lot about animals, with books on Rin Tin Tin and one collecting her animal pieces. There was also, of course, The Library Book, about the wild history of the main Los Angeles public library. But it’s her The Orchid Thief – and the movie (not) based on it, Adaptation – that’s among my favourites, so the long section on that was the biggest thrill for me. There are also black-and-white images scattered through.

It was slightly unfortunate that I read this at the same time as Book of Lives – who could compete with Margaret Atwood? – but it is, yes, a joy to read about Orlean’s writing life. She’s full of enthusiasm and good sense, depicting the vocation as part toil and part magic:

“I find superhuman self-confidence when I’m working on a story. The bashfulness and vulnerability that I might otherwise experience in a new setting melt away, and my desire to connect, to observe, to understand, powers me through.”

“I like to do a gut check any time I dismiss or deplore something I don’t know anything about. That feels like reason enough to learn about it.”

“anything at all is worth writing about if you care about it and it makes you curious and makes you want to holler about it to other people”

With thanks to Atlantic Books for the free copy for review.

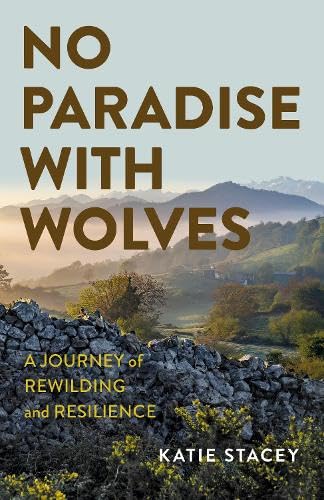

No Paradise with Wolves: A Journey of Rewilding and Resilience by Katie Stacey

I had the good fortune to visit Wild Finca, Luke Massey and Katie Stacey’s rewilding site in Asturias, while on holiday in northern Spain in May 2022, and was intrigued to learn more about their strategy and experiences. This detailed account of the first four years begins with their search for a property in 2018 and traces the steps of their “agriwilding” of a derelict farm: creating a vegetable garden and tending to fruit trees, but also digging ponds, training up hedgerows, and setting up rotational grazing. Their every decision went against the grain. Others focussed on one crop or type of livestock while they encouraged unruly variety, keeping chickens, ducks, goats, horses and sheep. Their neighbours removed brush in the name of tidiness; they left the bramble and gorse to welcome in migrant birds. New species turned up all the time, from butterflies and newts to owls and a golden fox.

Luke is a wildlife guide and photographer. He and Katie are conservation storytellers, trying to get people to think differently about land management. The title is a Spanish farmers’ and hunters’ slogan about the Iberian wolf. Fear of wolves runs deep in the region. Initially, filming wolves was one of the couple’s major goals, but they had to step back because staking out the animals’ haunts felt risky; better to let them alone and not attract the wrong attention. (Wolf hunting was banned across Spain in 2021.) There’s a parallel to be found here between seeing wolves as a threat and the mild xenophobia the couple experienced. Other challenges included incompetent house-sitters, off-lead dogs killing livestock, the pandemic, wildfires, and hunters passing through weekly (as in France – as we discovered at Le Moulin de Pensol in 2024 – hunters have the right to traverse private land in Spain).

Luke and Katie hope to model new ways of living harmoniously with nature – even bears and wolves, which haven’t made it to their land yet, but might in the future – for the region’s traditional farmers. They’re approaching self-sufficiency – for fruit and vegetables, anyway – and raising their sons, Roan and Albus, to love the wild. We had a great day at Wild Finca: a long tour and badger-watching vigil (no luck that time) led by Luke; nettle lemonade and sponge cake with strawberries served by Katie and the boys. I was clear how much hard work has gone into the land and the low-impact buildings on it. With the exception of some Workaway volunteers, they’ve done it all themselves.

Katie Stacey’s storytelling is effortless and conversational, making this impassioned memoir a pleasure to read. It chimed perfectly with Hoffman’s writing (above) about the fear of bears and wolves, and reparation policies for farmers, in Europe. I’d love to see the book get a bigger-budget release complete with illustrations, a less misleading title, the thorough line editing it deserves, and more developmental work to enhance the literary technique – as in the beautiful final chapter, a present-tense recreation of a typical walk along The Loop. All this would help to get the message the wider reach that authors like Isabella Tree have found. “I want to be remembered for the wild spaces I leave behind,” Katie writes in the book’s final pages. “I want to be remembered as someone who inspired people to seek a deeper connection to nature.” You can’t help but be impressed by how much of a difference two people seeking to live differently have achieved in just a handful of years. We can all rewild the spaces available to us (see also Kate Bradbury’s One Garden against the World), too.

With thanks to Earth Books (Collective Ink) for the free copy for review.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

#1952Club: Patricia Highsmith, Paul Tillich & E.B. White

Simon and Karen’s classics reading weeks are always a great excuse to pick up some older books. I assembled an unlikely trio of lesbian romance, niche theology, and an animal-lover’s children’s classic.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith

Originally published as The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, this is widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending (it’s more open-ended, really, but certainly not tragic; suicide was a common consequence in earlier fiction). Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer in New York City, takes a job selling dolls in a department store one Christmas season. Her boyfriend, Richard, is a painter and has promised to take her to Europe, but she’s lukewarm about him and the physical side of their relationship has never interested her. One day, a beautiful blonde woman in a fur coat – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – comes to her counter to order a doll and have it sent to her out in New Jersey. Therese sends a Christmas card to the same address, and the women start meeting up for drinks and meals.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

The second half of the book has Carol and Therese setting out on a road trip out West. It should be an idyllic consummation, but they realize they’re being trailed by a private detective collecting evidence for Carol’s husband Harge to use against her in a custody battle. I was reminded of the hunt for Humbert Humbert and his charge in Lolita; “the whole world was ready to be their enemy,” Therese realizes, and to consider their relationship “sordid and pathological,” as Richard describes it in a letter.

The novel is a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds against it. I’d read five of Highsmith’s mysteries and thought them serviceable but nothing special (I don’t read crime in general). This does, however, share their psychological intensity and the suspense about how things will play out. Highsmith gives details about Therese’s early life and Carol’s previous intimate friendship that help to explain some things but never reduce either character to a diagnosis or a tendency. Neither of them wanted just anyone, some woman; it was this specific combination of souls that sparked at first sight. (Secondhand from a charity shop that closed long ago, so I know I’d had it on my shelf unread since 2016!) ![]()

The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

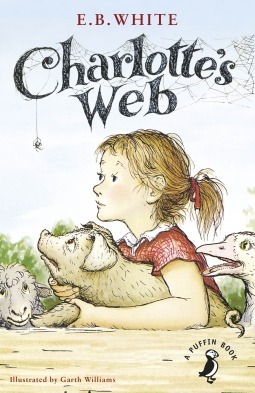

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

Charlotte is a fine specimen of a barn spider, well spoken and witty. She puts her mind to saving Wilbur’s bacon by weaving messages into her web, starting with “Some Pig.” He’s soon a county-wide spectacle, certain to survive the chop. But a farm is always, inevitably, a place of death. White fashions such memorable characters, including Templeton the gluttonous rat, and captures the hope of new life returning as the seasons turn over. Talking animals aren’t difficult to believe in when Fern can hear every word they say. The black-and-white line drawings are adorable. And making readers care about invertebrates? That’s a lasting achievement. I’m sure I read this several times as a child, but I appreciated it all the more as an adult. (Little Free Library) ![]()

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, and 1970 Club.

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

August Releases: Sarah Manguso (Fiction), Sarah Moss (Memoir), and Carl Phillips (Poetry)

Today I feature a new-to-me poet and two women writers whose careers I’ve followed devotedly but whose latest books – forthright yet slippery; their genre categories could easily be reversed – I found very emotionally difficult to read. Gruelling, almost, but admirable. Many rambling thoughts ensue. Then enjoy a nice poem.

Liars by Sarah Manguso

As part of a profile of Manguso and her oeuvre for Bookmarks magazine, I wrote a synopsis and surveyed critical opinion; what follow are additional subjective musings. I’ve read six of her nine books (all but the poetry and an obscure flash fiction collection) and I esteem her fragmentary, aphoristic prose, but on balance I’m fonder of her nonfiction. Had Liars been marketed as a diary of her marriage and divorce, Manguso might have been eviscerated for the indulgence and one-sided presentation. With the thinnest of autofiction layers, is it art?

Jane recounts her doomed marriage, from the early days of her relationship with John Bridges to the aftermath of his affair and their split. She is a writer and academic who sacrifices her career for his financially risky artistic pursuits. Especially once she has a baby, every domestic duty falls to her, while he keeps living like a selfish stag and gaslights her if she tries to complain, bringing up her history of mental illness. The concise vignettes condense 14+ years into 250 pages, which is a relief because beneath the sluggish progression is such repetition of type of experiences that it could feel endless. John’s last name might as well be Doe: The novel presents him – and thus all men – as despicable and useless, while women are effortlessly capable and, by exhausting themselves, achieve superhuman feats. This is what heterosexual marriage does to anyone, Manguso is arguing. Indeed, in a Guardian interview she characterized this as a “domestic abuse novel,” and elsewhere she has said that motherhood can be unlinked from patriarchy, but not marriage.

Let’s say I were to list my every grievance against my husband from the last 17+ years: every time he left dirty clothes on the bedroom floor (which is every day); every time he loaded the dishwasher inefficiently (which is every time, so he leaves it to me); every time he failed to seal a packet or jar or Tupperware properly (which – yeah, you get the picture) – and he’s one of the good guys, bumbling rather than egotistical! And he’d have his own list for me, too. This is just what we put up with to live with other people, right? John is definitely worse (“The difference between John and a fascist despot is one of degree, not type”). But it’s not edifying, for author or reader. There may be catharsis to airing every single complaint, but how does it help to stew in bitterness? Look at everything I went through and validate my anger.

There are bright spots: Jane’s unexpected transformation into a doting mother (but why must their son only ever be called “the child”?), her dedication to her cat, and the occasional dark humour:

So at his worst, my husband was an arrogant, insecure, workaholic, narcissistic bully with middlebrow taste, who maintained power over me by making major decisions without my input or consent. It could still be worse, I thought.

Manguso’s aphoristic style makes for many quotably mordant sentences. My feelings vacillated wildly, from repulsion to gung-ho support; my rating likewise swung between extremes and settled in the middle. I felt that, as a feminist, I should wholeheartedly support a project of exposing wrongs. It’s easy to understand how helplessness leads to rage, and how, considering sunk costs, a partner would irrationally hope for a situation to improve. So I wasn’t as frustrated with Jane as some readers have been. But I didn’t like the crass sexual language, and on the whole I agreed with Parul Sehgal’s brilliant New Yorker review that the novel is so partial and the tone so astringent that it is impossible to love. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the proof copy for review.

And a quote from the Moss memoir (below) to link the two books: “Homes are places where vulnerable people are subject to bullying, violence and humiliation behind closed doors. Homes are places where a woman’s work is never done and she is always guilty.”

20 Books of Summer, #19:

My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

I’ve reviewed this memoir for Shelf Awareness (it’s coming out in the USA from Farrar, Straus and Giroux on October 22nd) so will only give impressions, in rough chronological order:

Sarah Moss returns to nonfiction – YES!!!

Oh no, it’s in the second person. I’ve read too much of that recently. Fine for one story in a collection. A whole book? Not so sure. (Kirsty Logan got away with it, but only because The Unfamiliar is so short and meant to emphasize how matrescence makes you other.)

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

The constant second-guessing of memory via italicized asides that question or refute what has just been said; the weird nicknames (her father is “the Owl” and her mother “the Jumbly Girl”) – in short, the deliberate artifice – at first kept me from becoming submerged. This must be deliberate and yet meant it was initially a chore to pick up. It almost literally hurt to read. And yet there are some breathtakingly brilliant set pieces. Oh! when her mother’s gay friend Keith buys her a chocolate éclair and she hides it until it goes mouldy.

Once she starts discussing her childhood reading – what it did for her then and how she views it now – the book really came to life for me. And she very effectively contrasts the would-be happily ever after of generally getting better after eight years of disordered eating with her anorexia returning with a vengeance at age 46 – landing her in A&E in Dublin. (Oh! when she reads War and Peace over and over on a hospital bed and defiantly uses the clean toilets on another floor.) This crisis is narrated in the third person before a return to second person.

The tone shifts throughout the book, so that what threatens to be slightly cloying in the childhood section turns academically curious and then, somehow, despite the distancing pronouns, intimate. So much so that I found myself weeping through the last chapters over this lovely, intelligent woman’s ongoing struggles. As an overly cerebral person who often thinks it’s pesky to have to live in a body, I appreciated her probing of the body/mind divide; and as she tracks where her food issues came from, I couldn’t help but think about my sister’s years of eating disorders and my mother’s fear that it was all her fault.

Beyond Moss’s usual readers, I’d also recommend this to fans of Laura Freeman’s The Reading Cure and Noreen Masud’s A Flat Place.

Overall: shape-shifting, devastating, staunchly pragmatic. I’m not convinced it all hangs together (and I probably would have ended it at p. 255), but it’s still a unique model for transmuting life into art. ![]()

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Scattered Snows, to the North by Carl Phillips

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Phillips is a prolific poet I’d somehow never heard of. In fact, he won the Pulitzer Prize last year for his selected poetry volume. He’s gay and African American, and in his evocative verse he summons up landscapes and a variety of weather, including as a metaphor for emotions – guilt, shame, and regret. Looking back over broken relationships, he questions his memory.

Will I remember individual poems? Unlikely. But the sense of chilly, clear-eyed reflection, yes. (Sample poem below) ![]()

With thanks to Carcanet for the advanced e-copy for review.

Record of Where a Wind Was

Wave-side, snow-side,

little stutter-skein of plovers

lifting, like a mind

of winter—

We’d been walking

the beach, its unevenness

made our bodies touch,

now and then, at

the shoulders mostly,

with that familiarity

that, because it sometimes

includes love, can

become confused with it,

though they remain

different animals. In my

head I played a game with

the waves called Weapon

of Choice, they kept choosing

forgiveness, like the only

answer, as to them

it was, maybe. It’s a violent

world. These, I said, I choose

these, putting my bare hands

through the air in front of me.

Any other August releases you’d recommend?

Spring Reads, Part II: Blossomise, Spring Chicken & Cold Spring Harbor

Our garden is an unruly assortment of wildflowers, rosebushes, fruit trees and hedge plants, along with an in-progress pond, and we’ve made a few half-hearted attempts at planting vegetable seeds and flower bulbs. It felt more like summer earlier in May, before we left for France; as the rest of the spring plays out, we’ll see if the beetroot, courgettes, radishes and tomatoes amount to anything. The gladioli have certainly been shooting for the sky!

I recently encountered spring (if only in name) through these three books, a truly mixed bag: a novelty poetry book memorable more for the illustrations than for the words, a fascinating popular account of the science of ageing, and a typically depressing (if you know the author, anyway) novel about failing marriages and families. Part I of my Spring Reading was here.

Blossomise by Simon Armitage; illus. Angela Harding (2024)

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

Armitage has been the Poet Laureate for yonks now, but I can’t say his poetry has ever made much of an impression on me. That’s especially true of this slim volume commissioned by the National Trust: it’s 3 stars for Angela Harding’s lovely if biologically inaccurate (but I’ll be kind and call them whimsical) engravings, and 2 stars for the actual poems, which are light on content. Plum, cherry, apple, pear, blackthorn and hawthorn blossom loom large. It’s hard to describe spring without resorting to enraptured clichés, though: “Planet Earth in party mode, / petals fizzing and frothing / like pink champagne.” The haiku (11 of 21 poems) feel particularly tossed-off: “The streets are learning / the language of plum blossom. / The trees have spoken.” But others are sure to think more of this than I did.

A favourite passage: “Scented and powdered / she’s staging / a one-tree show / with hi-viz blossoms / and lip-gloss petals; / she’ll season the pavements / and polished stones / with something like snow.” (Public library) ![]()

Spring Chicken: Stay Young Forever (or Die Trying) by Bill Gifford (2015)

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Gifford was in his mid-forties when he undertook this quirky journey into the science and superstitions of ageing. As a starting point, he ponders the differences between his grandfather, who swam and worked his orchard until his death from infection at 86, and his great-uncle, not so different in age, who developed Alzheimer’s and died in a nursing home at 74. Why is the course of ageing so different for different people? Gifford suspects that, in this case, it had something to do with Uncle Emerson’s adherence to the family tradition of Christian Science and refusal to go to the doctor for any medical concern. (An alarming fact: “The Baby Boom generation is the first in centuries that has actually turned out to be less healthy than their parents, thanks largely to diabetes, poor diet, and general physical laziness.”) But variation in healthspan is still something of a mystery.

Over the course of the book, Gifford meets all number of researchers and cranks as he attends conferences, travels to spend time with centenarians and scientists, and participates in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. There have been some truly zany ideas about how to pause or reverse aging, such as self-dosing with hormones (Suzanne Somers is one proponent), but long-term use is discouraged. Some things that do help, to an extent, are calorie restriction and periodic fasting plus, possibly, red wine, coffee and aspirin. But the basic advice is nothing we don’t already know about health: don’t eat too much and exercise, i.e., avoid obesity. The layman-interpreting-science approach reminded me of Mary Roach’s. There was some crossover in content with Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine and various books I’ve read about dementia. Fun and enlightening. (New purchase – bargain book from Dollar Tree, Bowie, MD) ![]()

Cold Spring Harbor by Richard Yates (1986)

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Cold Spring Harbor is a Long Island hamlet whose name casts an appropriately chilly shadow over this slim novel about families blighted by alcoholism and poor decisions. Evan Shepard, only in his early twenties, already has a broken marriage behind him after a teenage romance led to an unplanned pregnancy. Mary and their daughter Kathleen seem to be in the rearview mirror as he plans to return to college for an engineering degree. One day he accompanies his father into New York City for an eye doctor appointment and the car breaks down. The men knock on a random door and thereby become entwined with the Drakes: Gloria, the unstable, daytime-drinking mother; Rachel, her beautiful daughter; and Phil, her earnest but unconfident adolescent son.

Evan and Rachel soon marry and agree to Gloria’s plan of sharing a house in Cold Spring Harbor, where the Shepards live (Evan’s mother is also an alcoholic, but less functional; she hides behind the “invalid” label). Take it from me: living with your in-laws is never a good idea! As the Second World War looms, and with Evan and Rachel expecting a baby, it’s clear something will have to give with this uneasy family arrangement, but the dramatic break I was expecting – along the lines of a death or accident – never arrived. Instead, there’s just additional slow crumbling, and the promise of greater suffering to come. Although Yates’s character portraits are as penetrating as in Easter Parade, I found the plot a little lacklustre here. (Secondhand – Clutterbooks, Sedbergh) ![]()

Any ‘spring’ reads for you recently?

Jane of Lantern Hill by L.M. Montgomery (1937) #ReadingLanternHill

I’m grateful to Canadian bloggers Naomi (Consumed by Ink) and Sarah for hosting the readalong: It’s been a pure pleasure to discover this lesser-known work by Lucy Maud Montgomery.

{SOME SPOILERS IN THE FOLLOWING}

Like Anne of Green Gables, this is a cosy novel about finding a home and a family. Fairytale-like in its ultimate optimism, it nevertheless does not avoid negative feelings. It also seemed to me ahead of its time in how it depicts parental separation.

Jane Victoria Stuart lives with her beautiful, flibbertigibbet mother and strict grandmother in a “shabby genteel” mansion on the ironically named Gay Street in Toronto. Grandmother calls her Victoria and makes her read the Bible to the family every night, a ritual Jane hates. Jane is an indifferent student, though she loves writing, and her best friend is Jody, an orphan who is in service next door. Her mother is a socialite breezing out each evening, but she doesn’t seem jolly despite all the parties. Jane has always assumed her father is dead, so it is a shock when a girl at school shares the rumour that her father is alive and living on Prince Edward Island. Apparently, divorce was difficult in Canada at that time and would have required a trip to the USA, so for nearly a decade the couple have been estranged.

It’s not just Jane who feels imprisoned on Gay Street: her mother and Jody are both suffering in their own ways, and long to live unencumbered by others’ strictures. For Jane, freedom comes when her father requests custody of her for the summer. Grandmother is of a mind to ignore the summons, but the wider family advise her to heed it. Initially apprehensive, Jane falls in love with PEI and feels like she’s known her father, a jocular writer, all the time. They’re both romantics and go hunting for a house that will feel like theirs right away. Lantern Hill fits the bill, and Jane delights in playing the housekeeper and teaching herself to cook and garden. Returning to Toronto in the autumn is a wrench, but she knows she’ll be back every summer. It’s an idyll precisely because it’s only part time; it’s a retreat.

Jane is an appealing heroine with her can-do attitude. Her everyday adventures are sweet – sheltering in a barn when the car breaks down, getting a reward and her photo in the paper for containing an escaped circus lion – but I was less enamoured with the depiction of the quirky locals. The names alone point to country bumpkin stereotypes: Shingle Snowbeam, Ding-dong, the Jimmy Johns. I did love Little Aunt Em, however, with her “I smack my lips over life” outlook. Meddlesome Aunt Irene could have been less one-dimensional; Jody’s adoption by the Titus sisters is contrived (and closest in plot to Anne); and Jane’s late illness felt unnecessary. While frequent ellipses threatened to drive me mad, Montgomery has sprightly turns of phrase: “A dog of her acquaintance stopped to speak to her, but Jane ignored him.”

Could this have been one of the earliest stories of a child who shuttles back and forth between separated or divorced parents? I wondered if it was considered edgy subject matter for Montgomery. There is, however, an indulging of the stereotypical broken-home-child fantasy of the parents still being in love and reuniting. If this is a fairytale setup, Grandmother is the evil ogre who keeps the princess(es) locked up in a gloomy castle until the noble prince’s rescue. I’m sure both Toronto and PEI are lovely in their own way – alas, I’ve never been to Canada – and by the end Montgomery offers Jane a bright future in both.

Small qualms aside, I loved reading Jane of Lantern Hill and would recommend it to anyone who enjoyed the Anne books. It’s full of the magic of childhood. What struck me most, and will stick with me, is the exploration of how the feeling of being at home (not just having a house to live in) is essential to happiness. (University library)

#ReadingLanternHill

Buy Jane of Lantern Hill from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]