20 Books of Summer, 11–13: Campbell, Julavits, Lu

Two solid servings of women’s life writing plus a novel about a Chinese woman stuck in roles she’s not sure she wants anymore.

Thunderstone: A true story of losing one home and discovering another by Nancy Campbell (2022)

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

Just before Covid hit, Campbell’s partner Anna had a partially disabling stroke. They had to adjust to lockdown and the rigours of Anna’s at-home care at once. It was complicated in that Campbell was already halfway out the door: after 10 years, their relationship had run its course and she knew it was time to go, but guilt lingered about abandoning Anna at her most vulnerable (“How dare I leave someone who needed me”). That is the backdrop to a quiet book largely formed of a diary spanning June to September 2021. Campbell recounts settling into a caravan by the canal and railway line in Oxford, getting plenty of help from friends and neighbours but also finding her own inner resources and enjoying her natural setting.

The title refers to a fossil that has been considered a talisman in various cultures, and she needed the good luck during a period that involved accidental carbon monoxide poisoning and surgery for an ovarian abnormality (but it didn’t protect her books, which were all destroyed in a leaking shipping container – the horror!). I most enjoyed the longer entries where she muses on “All the potential lives I moved on from” during 20 years in Oxford and elsewhere, which makes me think that I would have preferred a more traditional memoir by her. Covid narratives feel really dated now, unfortunately. (New (bargain) purchase from Hungerford Bookshop with birthday voucher)

Directions to Myself: A Memoir by Heidi Julavits (2023)

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Julavits is a novelist and founding editor of The Believer. I loved her non-standard diary, The Folded Clock, back in 2017, so jumped at the chance to read her new memoir but then took more a year over reading it. The U.S. subtitle, “A Memoir of Four Years,” captures the focus: the change in her son from age five to age nine – from little boy to full-fledged individual. In later sections he sounds so like my American nephew with his Fortnite obsession and lawyerly levels of argumentation and self-justification. A famous author once told Julavits that writers should not have children because each one represents a book they will not write. This book is a rebuttal: something she could not have written without having had her son. Home is a New York City apartment near the Columbia University campus where she teaches – in fact, directly opposite a dorm at which rape allegations broke out – but more often the setting is their Maine vacations, where coastal navigation is a metaphor for traversing life.

Mostly the memoir takes readers through everyday conversations the author has with friends and family about situations of inequality or harassment. Through her words she tries to gently steer her son towards more open-minded ideas about gender roles. She also entrances him and his sleepover friends with a real-life horror story about being chased through the French countryside by a man in a car. The tenor of her musings appealed to me, but already the details are fading. I suspect this will mean much more to a parent.

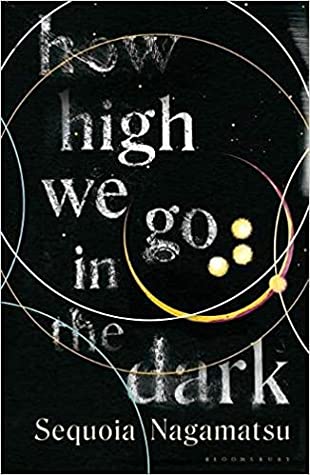

With thanks to Bloomsbury for the free copy for review.

The Funeral Cryer by Wenyan Lu (2023)

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

The title character holds a traditional position in her Chinese village, performing mourning at ceremonies for the dead. It’s a steady source of income for her and her husband, but her career choice has stigma attached: “Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat.” Exotic as the setup might seem at first, it underpins a familiar story of a woman caught in frustrating relationships and situations. A very readable but plain style to this McKitterick Prize winner.

With thanks to the Society of Authors for the free copy.

The Rituals by Rebecca Roberts (Blog Tour)

Rebecca Roberts adapted her 2022 Welsh-language novel Y Defodau, her ninth, into The Rituals, which draws on her time working as a non-religious celebrant. Her protagonist, Gwawr Efa Taylor, is a freelance celebrant, too. The novel is presented as her notebook, containing diary entries as well as the text of some of the secular ceremonies she performs to mark rites of passage. We open on a funeral for a 39-year-old woman, then swiftly move on to a Bridezilla celebrity’s wedding that sours in a way that threatens to derail Gwawr’s entire career. A victim of sabotage, she’s doubly punished by gossip.

As she tries to piece her life back together, Gwawr finds support from many quarters, such as her beloved grandfather (Taid), a friend who invites her along on a writing retreat, her Welsh-language book club, a high school acquaintance, other customers and a sweet dog. She and the widower from the first funeral make a pact to start counselling at the same time to work through their grief – we know early on that she has experienced the devastating loss of Huw, but the details aren’t revealed until later. A couple of romantic prospects emerge for the 37-year-old, but also some uncomfortable reminders of past scandal.

There are heavy issues here, like alcoholism, infant loss and suicide, but they reflect the range of human experience and allow compassionate connections to form. Gwawr’s empathy is motivated by her bereavement: “That’s what keeps me going – knowing that I’ve turned the worst time of my life into something that helps other people. Taking the good from the bad.” You can see that attitude infusing her naming ceremonies and funerals. I’ll say no more about the plot, just that it prioritizes moments of high emotion and is both absorbing and touching.

I think this is only the second Welsh-language book I have read in translation (the first was The Life of Rebecca Jones by Angharad Price). It’s whetted my appetite for heading back to Wales for the first time since 2020 – we’re off to Hay-on-Wye on Friday. The Rituals is a tear-jerker for sure, but also sweet, romantic and realistic. I enjoyed it in much the same way I did The Collected Regrets of Clover by Mikki Brammer, and was pleased to try something from a small press that champions women’s writing.

With thanks to Random Things Tours and Honno Welsh Women’s Press for the proof copy for review.

Buy The Rituals from Bookshop.org [affiliate link]

I was delighted to be part of the blog tour for The Rituals. See below for details of where other reviews have appeared or will be appearing soon.

The Clock Winder by Anne Tyler (1972)

This year I’m joining in Liz’s Anne Tyler readalong for all of the Tyler novels that I own and haven’t read yet (at least the ones I can access; others are marooned in a box in the States). The Clock Winder was Tyler’s fourth novel and the first to take place in Baltimore, her trademark setting. It’s the earliest of her works that I’ve read. (See also Liz’s review.)

When I reviewed Clock Dance back in 2018, I wondered if there could be a connection between the two novels beyond their titles. A clock, of course, symbolizes the passage of time, so invites us to think about how the characters change and what stays the same over the years. But there is, in fact, another literal link: in both books, there is a fairly early mention of a gun – and, if you know your Chekhov quotes, that means it’s going to go off. Whereas in Clock Dance the gunshot has no major consequences, here it’s a method of suicide. So the major thing to surprise me about The Clock Winder is that it goes to a dark place that Tyler’s fiction rarely visits, though an additional later threat comes to nothing.

As the novel opens in 1960, Pamela Emerson fires the Black handyman who has worked for her for 25 years. “The house had outlived its usefulness,” what with Mr. Emerson dead these three months and all seven children grown up and moved out. Mrs. Emerson likes to keep up appearances – her own hair and makeup, and the house’s porch furniture, which a passerby helps her move. This helpful stranger is Elizabeth Abbott, a Baptist preacher’s daughter from North Carolina who is taking on odd jobs to pay for her senior year of college. Mrs. Emerson hires Elizabeth as her new ‘handyman’ for $40 a week. One of her tasks is to wind all the clocks in the house. Though she’s a tall tomboy, Elizabeth attracts a lot of suitors – including two of the Emerson sons, Timothy and Matthew.

As the novel opens in 1960, Pamela Emerson fires the Black handyman who has worked for her for 25 years. “The house had outlived its usefulness,” what with Mr. Emerson dead these three months and all seven children grown up and moved out. Mrs. Emerson likes to keep up appearances – her own hair and makeup, and the house’s porch furniture, which a passerby helps her move. This helpful stranger is Elizabeth Abbott, a Baptist preacher’s daughter from North Carolina who is taking on odd jobs to pay for her senior year of college. Mrs. Emerson hires Elizabeth as her new ‘handyman’ for $40 a week. One of her tasks is to wind all the clocks in the house. Though she’s a tall tomboy, Elizabeth attracts a lot of suitors – including two of the Emerson sons, Timothy and Matthew.

We meet the rest of the Emerson clan at the funeral for the aforementioned suicide. There’s a very good post-funeral meal scene reminiscent of Carol Shields’s party sequences: disparate conversations reveal a lot about the characters. “We’re event-prone,” Matthew writes in a letter to Elizabeth. “But sane, I’m sure of that. Even Andrew [in a “rest home” for the mentally ill] is, underneath. Probably most families are event-prone, it’s just that we make more of it.” In the years to come, Elizabeth tries to build a life in North Carolina but keeps being drawn back into the Emersons’ orbit: “Life seemed to be a constant collision … everything recurred. She would keep running into Emersons until the day she died”.

The main action continues through 1965 and there is a short finale set in 1970. While I enjoyed aspects of the characters’ personalities and interactions, the decade span felt too long and the second half is very rambly. A more condensed timeline might have allowed for more of the punchy family scenes Tyler is so good at, even this early in her career. (There is a great left-at-the-altar scene in which the bride utters “I don’t” and flees!) Still, Elizabeth is an appealing antihero and the setup is out of the ordinary. I liked comparing Baltimore then and now: in 1960 you get a turkey being slaughtered in the backyard for Thanksgiving, and pipe smoking in the grocery store. It truly was a different time. One nice detail that persists is the 17-year cicadas.

You can see the seeds of some future Tyler elements here: large families, sibling romantic rivalries, secrets, ageing and loss. The later book I was reminded of most was Back When We Were Grown-ups, in which a stranger is accepted into a big, bizarre family and has to work out what role she is to play. A Tyler novel is never less than readable, but this ended up being my least favorite of the 12 I’ve read so far, so I doubt I’ll read the three that preceded it. Those 12, in order of preference (greatest to least), are:

Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant

Ladder of Years

The Accidental Tourist

Breathing Lessons

Digging to America

Vinegar Girl

Clock Dance

Back When We Were Grown-ups

A Blue Spool of Thread

The Beginner’s Goodbye

Redhead by the Side of the Road

The Clock Winder

Source: Charity shop

My rating:

Next up for me will be Earthly Possessions in mid-April.

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

It’s just over five years since many of us were introduced to Wigtown and the ups and downs of running a bookshop there through Shaun Bythell’s

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

An indigenous human rights lawyer, Aguon is passionate about protecting his homeland of Guam, which is threatened by climate change and military expansion. His tender collage of autobiographical vignettes and public addresses inspires activism and celebrates beauty worth preserving. The U.S. Department of Defense’s plan to site more Marines and firing ranges on Guam will destroy more than 1,000 acres of limestone forest—home to endemic and endangered species, including the Mariana eight-spot butterfly. Aguon has been a lead litigator in appeals rising all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Rejecting fatalism, he endorses peaceful resistance. Two commencement speeches, poems, a eulogy and an interview round out the varied and heartfelt collection.

Capildeo is a nonbinary Trinidadian Scottish poet and the current University of York writer in residence. Their fourth collection is richly studded with imagery of the natural world, especially birds and trees. “In Praise of Birds” makes a gorgeous start:

Capildeo is a nonbinary Trinidadian Scottish poet and the current University of York writer in residence. Their fourth collection is richly studded with imagery of the natural world, especially birds and trees. “In Praise of Birds” makes a gorgeous start:

The virus is highly transmissible and deadly, and later found to mostly affect children. In the following 13 stories (most about Asian Americans in California, plus a few set in Japan), the plague is a fact of life but has also prompted a new relationship to death – a major thread running through is the funerary rites that have arisen, everything from elegy hotels to “resomation.” In the stand-out story, the George Saunders-esque “City of Laughter,” Skip works at a euthanasia theme park whose roller coasters render ill children unconscious before stopping their hearts. He’s proud of his work, but can’t approach it objectively after he becomes emotionally involved with Dorrie and her son Fitch, who arrives in a bubble.

The virus is highly transmissible and deadly, and later found to mostly affect children. In the following 13 stories (most about Asian Americans in California, plus a few set in Japan), the plague is a fact of life but has also prompted a new relationship to death – a major thread running through is the funerary rites that have arisen, everything from elegy hotels to “resomation.” In the stand-out story, the George Saunders-esque “City of Laughter,” Skip works at a euthanasia theme park whose roller coasters render ill children unconscious before stopping their hearts. He’s proud of his work, but can’t approach it objectively after he becomes emotionally involved with Dorrie and her son Fitch, who arrives in a bubble. This is just the sort of wide-ranging popular science book that draws me in. Like

This is just the sort of wide-ranging popular science book that draws me in. Like  I was delighted to be sent a preview pamphlet containing the author’s note and title essay of How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, coming from Atlantic in August. This guide to cultural criticism – how to read anything, not just a book – is alive to the biased undertones of everyday life. “Anyone who is perfectly comfortable with keeping the world just as it is now and reading it the way they’ve always read it … cannot be trusted”. Castillo writes that it is not the job of people of colour to enlighten white people (especially not through “the gooey heart-porn of the ethnographic” – war, genocide, tragedy, etc.); “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. This is bold, provocative stuff. I’m sure to learn a lot.

I was delighted to be sent a preview pamphlet containing the author’s note and title essay of How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, coming from Atlantic in August. This guide to cultural criticism – how to read anything, not just a book – is alive to the biased undertones of everyday life. “Anyone who is perfectly comfortable with keeping the world just as it is now and reading it the way they’ve always read it … cannot be trusted”. Castillo writes that it is not the job of people of colour to enlighten white people (especially not through “the gooey heart-porn of the ethnographic” – war, genocide, tragedy, etc.); “if our stories primarily serve to educate, console and productively scold a comfortable white readership, then those stories will have failed their readers”. This is bold, provocative stuff. I’m sure to learn a lot.