#ReadingtheMeow2025, Part I: Books by Gustafson, Inaba, Tomlinson and More

It’s the start of the third annual week-long Reading the Meow challenge, hosted by Mallika of Literary Potpourri! For my first set of reviews, I have two lovely memoirs of life with cats, and a few cute children’s books.

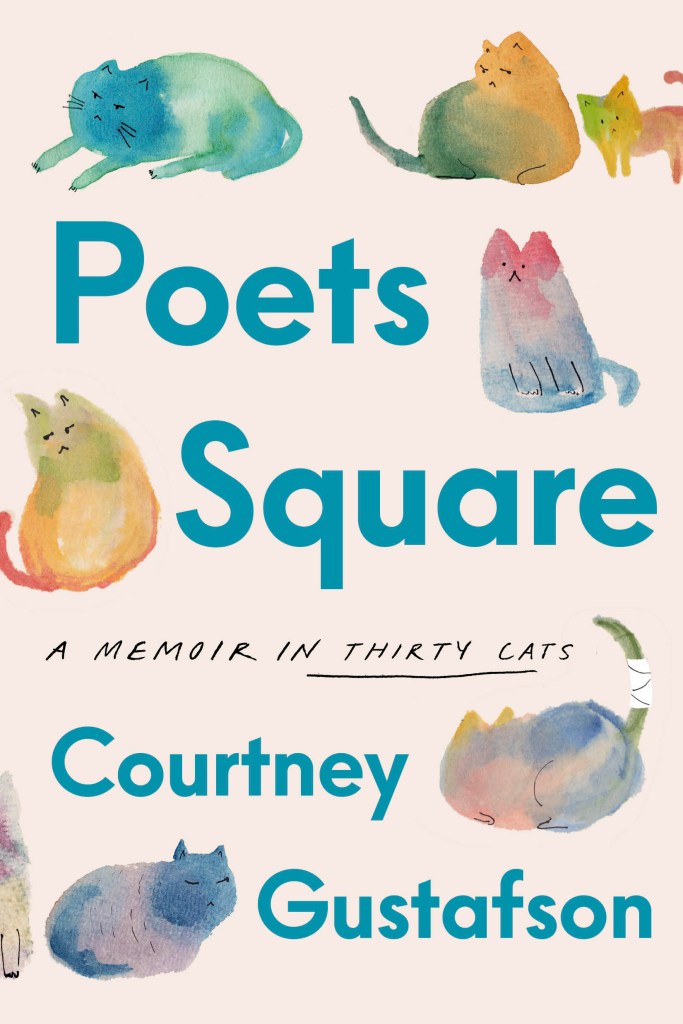

Poets Square: A Memoir in Thirty Cats by Courtney Gustafson (2025)

This was on my Most Anticipated list and surpassed my expectations. Because I’m a snob and knew only that the author was a young influencer, I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of the prose and the depth of the social analysis. After Gustafson left academia, she became trapped in a cycle of dead-end jobs and rising rents. Working for a food bank, she saw firsthand how broken systems and poverty wear people down. She’d recently started feeding and getting veterinary care for the 30 feral cats of a colony in her Poets Square neighbourhood in Tucson, Arizona. They all have unique personalities and interactions, such as Sad Boy and Lola, a loyal bonded pair; and MK, who made Georgie her surrogate baby. Gustafson doled out quirky names and made the cats Instagram stars (@PoetsSquareCats). Soon she also became involved in other local trap, neuter and release initiatives.

That the German translation is titled “Cats and Capitalism” gives an idea of how the themes are linked here: cat colonies tend to crop up where deprivation prevails. Stray cats, who live short and difficult lives, more reliably receive compassion than struggling people for whom the same is true. TNR work takes Gustafson to places where residents are only just clinging on to solvency or where hoarding situations have gotten out of control. I also appreciated a chapter that draws a parallel between how she has been perceived as a young woman and how female cats are deemed “slutty.” (Having a cat spayed so she does not undergo constant pregnancies is a kindness.) She also interrogates the “cat mom” stereotype through an account of her relationship with her mother and her own decision not to have children.

Gustafson knows how lucky she is to have escaped a paycheck-to-paycheck existence. Fame came seemingly out of nowhere when a TikTok video she posted about preparing a mini Thanksgiving dinner for the cats went viral. Social media and cat rescue work helped a shy, often ill person be less lonely, giving her “a community, a sense of rootedness, a purpose outside myself.” (Moreover, her Internet following literally ensured she had a place to live: when her rental house was being sold out from under her, a crowdfunding campaign allowed her to buy the house and save the cats.) However, they have also made her aware of a “constant undercurrent of suffering.” There are multiple cat deaths in the book, as you might expect. The author has become inured over time; she allows herself five minutes to cry, then moves on to help other cats. It’s easy to be overwhelmed or succumb to despair, but she chooses to focus on the “small acts of care by people trying hard” that can reduce suffering.

With its radiant portraits of individual cats and its realistic perspective on personal and collective problems, this is both a cathartic memoir and a probing study of how we build communities of care in times of hardship.

With thanks to Fig Tree (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

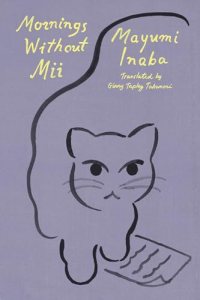

Mornings without Mii by Mayumi Inaba (1999; 2024)

[Translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori]

Inaba (1950–2014) was an award-winning novelist and poet. I can’t think why it took 25 years for this to be translated into English but assume it was considered a minor work of hers and was brought out to capitalize on the continuing success of cat-themed Japanese literature from The Guest Cat onward. Interestingly, it’s titled Mornings with Mii in the UK, which shifts the focus and is truer to the contents. Yes, by the end, Inaba is without Mii and dreading the days ahead, but before that she got 20 years of companionship. One day in the summer of 1977, Inaba heard a kitten’s cries on the breeze and finally located it, stuck so high in a school fence that someone must have left her there deliberately. The little fleabitten calico was named after the sound of her cry and ever after was afraid of heights.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

Inaba traces the turning of the seasons and the passing of the years through the changes they brought for her and for Mii. When she separated, moved to a new part of Tokyo, and started devoting her evenings to writing in addition to her full-time job, Mii was her closest friend. The new apartment didn’t have any green space, so instead of wandering in the woods Mii had to get used to exercising in the corridors. There were some scares: a surprise pregnancy nearly killed her, and once she went missing. And then there was the inevitable decline. Mii’s intestinal issues led to incontinence. For four years, Inaba endured her home reeking of urine. Many readers may, like me, be taken aback by how long Inaba kept Mii alive. She manually assisted the cat with elimination for years; 20 days passed between when Mii stopped eating and when she died. On the plus side, she got a “natural” death at home, but her quality of life in these years is somewhat alarming. I cried buckets through these later chapters, thinking of the friendship and intimate communion I had with Alfie. I can understand why Inaba couldn’t bear to say goodbye to Mii any earlier, especially because she’d lived alone since her divorce.

This memoir really captures the mixture of joy and heartache that comes with loving a pet. It’s an emotional connection that can take over your life in a good way but leave you bereft when it’s gone. There is nostalgia for the good days with Mii, but also regret and a heavy sense of responsibility. A number of the chapters end with a poem about Mii, but the prose, too, has haiku-like elegance and simplicity. It’s a beautiful book I can strongly recommend. (Read via Edelweiss)

let’s sleep

So as not to hear your departing footsteps

She won’t be here next year I know

I know we won’t have this time again

On this bright afternoon overcome with an unfathomable sadness

The greenery shines in my cat’s gentle eyes

I didn’t have any particular faith, but the one thing I did believe in was light. Just being in warm light, I could be with the people and the cat I had lost from my life. My mornings without Mii would start tomorrow. … Mii had returned to the light, and I would still be able to meet her there hundreds, thousands of times again.

The Cat Who Wanted to Go Home by Jill Tomlinson (1972)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

Suzy the cat lives in a French seaside village with a fisherman and his family of four sons. One day, she curls up to sleep in a basket only to wake up airborne – it’s a hot air balloon, taking her to England! Here the RSPCA place her with old Auntie Jo, who feeds her well, but Suzy longs to get back home. “Chez-moi” is her constant cry, which everyone thinks is an awfully funny way to say miaow (“She purred in French, [too,] but purring sounds the same all over the world”). Each day she hops into the basket of Auntie Jo’s bike for a ride to town to try a new route over the sea: in a kayak, on a surfboard, paddling alongside a Channel swimmer, and so on. Each attempt fails and she returns to her temporary lodgings: shared with a parrot named Biff and comfortable, yet not quite right. Until one day… This is a sweet little story (a 77-page paperback) for new readers to experience along with a parent, with just enough repetition to be soothing and a reassuring message about the benevolence of strangers. Susan Hellard’s illustrations are charming. (Secondhand – local library book sale)

And a couple of other children’s books:

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Mittens for Kittens and Other Rhymes about Cats, ed. Lenore Blegvad; illus. Erik Blegvad (1974) – A selection of traditional English and Scottish nursery rhymes, a few of them true to the nature of cats but most of them just nonsensical. You’ve got to love the drawings, though. (Secondhand – Hay Castle honesty shelves)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Scaredy Cat by Stuart Trotter (2007) – Rhyming couplets about everyday childhood fears and what makes them better. I thought it unfortunate that the young cat is afraid of other creatures; to be afraid of dogs is understandable, but three pages about not liking invertebrates is the wrong message to be sending. (Little Free Library)

Wendell Berry’s “Why I Am Not Going to Buy a Computer” & Why I Acquired My First Smartphone at Age 40.5

Wendell Berry is an American treasure: the 89-year-old Kentucky farmer is also a philosopher, poet, theologian, and writer of fiction, and many of his pronouncements bear the timeless wisdom of a biblical prophet. I’ve read his work from several genres and was curious to see how this 1987 essay – originally published in Harper’s Magazine and reprinted, along with some letters to the editor in response, plus extra commentary in the form of a 1990 essay, by Penguin in 2018 as the 50th and final entry in their Penguin Modern pamphlet series – might resonate with my own reluctance to adopt current technology.

The title essay is brief, barely filling 4.5 pages of a small-format paperback. It’s so concise that it would be difficult to summarize in many fewer words, but I’ll run through the points he makes across the initial essay, the replies to the correspondence, and a follow-up piece entitled “Feminism, the Body and the Machine” (1989). Berry laments his reliance on energy corporations and wants to limit that as much as possible. He decries consumerism in general; he isn’t going to acquire something just to be ‘keeping up with the times’. He doesn’t believe a computer will make his work better, and it doesn’t meet his criteria for a useful tool (smaller, cheaper and less energy-intensive than what it replaces; sourced locally and easily repaired by a non-specialist). He is perfectly happy with his current arrangement: he writes his work by hand and his wife types it up for him. He is loath to lose this human touch.

The letters to the editor, predictably, accuse him of self-righteousness for depicting his choice as the more virtuous one. The correspondents also felt they had to stand up for Berry’s wife, who might have better things to do than act as her husband’s secretary. This is the only time the author becomes slightly defensive, basically saying, ‘you don’t know anything about me, my wife or my marriage … maybe she wants to!’ He doubles down on the environmental harm caused by technology and consumerism, acknowledging his continued dependence on fossil fuels and vowing to avoid them, and unnecessary purchases, where possible.

If some technology does damage to the world, … then why is it not reasonable, and indeed moral, to try to limit one’s use of that technology?

To the extent that we consume, in our present circumstances, we are guilty. To the extent that we guilty consumers are conservationists, we are absurd. … can we do something directly to solve our share of the problem? … Why then is not my first duty to reduce, so far as I can, my own consumption?

If the use of a computer is a new idea, then a newer one is not to use one.

He even appears to speak prophetically to the rise of artificial intelligence:

My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can. … And in our time this means that we must save ourselves from the products that we are asked to buy in order, ultimately, to replace ourselves. The danger most immediately to be feared in ‘technological progress’ is the degradation and obsolescence of the body.

Certain of his arguments felt relevant to me as I ponder my own relationship to technology. I compose all my reviews on a 19-year-old personal computer that’s not connected to the Internet. I don’t listen to the radio and have seen maybe three films in the past two years. We’ve been television-free for a decade and I have never regretted it (Berry: “It is easy – it is even a luxury – to deny oneself the use of a television set, and I zealously practice that form of self-denial. Every time I see television (at other people’s houses), I am more inclined to congratulate myself on my deprivation.”).

I find it so hard to adjust to new tech that my reluctance may have shaded into suspicion. I’m certainly no early adopter, but I’d also object to the label “Luddite”: since 2013 I’ve been using e-readers, which are invaluable in my reviewing work. But for 15 years or more I have been looking at other people and their smartphones with disdain. I prided myself on my resistance. Stubbornness seemed like a virtue when the alternative was spending a lot of money on something I didn’t need.

Receiving my first cell phone in July 2004 (with my dad at left; at Dulles airport).

Two months ago, though, I finally gave in and accepted a hand-me-down Motorola Android phone from my father-in-law, after nearly 20 years of using an old-style mobile phone. As we were renegotiating our phone and Internet contract, I got virtually unlimited minutes and data on this device for £6/month, with no initial outlay. Had I been forced to make a purchase, I think I would still be holding out. But I had gotten to the point where refusal was cutting off my nose to spite my face. Why keep martyring myself – saying I couldn’t make important household phone calls because they drained my pay-as-you-go credit; learning complex workarounds to post to Instagram from my PC; taking crap photos on a digital camera held together with a rubber band? Why resist utility just for the sake of it?

To be clear, this was not a matter of saving time. I’m not a busy person. Plus I believe there is value in slowing down and acting deliberately. (See this book-based article I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2018 on the benefits of “wasting time.”) Mindless scrolling is as much a temptation on a PC as on a phone, so avoiding social media was not a motive for me; others with addictive tendencies may decide otherwise. Nor did I view convenience as reason enough per se. However, I admit I was attracted to the efficiency of a pocket-sized device that can at once replace a computer, pager, telephone, Rolodex, phonebook, camera, photo album, television screen, music player, camcorder, Dictaphone, stopwatch, calculator, map, satnav, flashlight, encyclopaedia, Kindle library, calendar, diary, Post-It notes, notebook, alarm clock and mirror. (Have I missed anything?) Talk about multi-tasking!

Out with the old, in with the new?

I would still say that I object to tech serving as a status symbol or a basis for self-importance, and I’d be pretty dubious about it ever being a worthwhile hobby. Should this phone fail me in future, I’ll copy my husband’s habit of buying a secondhand handset for £60–80. I wouldn’t acquire something that represented new extraction of rare resources. Treating things (or people) as disposable is anathema to me, something about which I know Berry would agree. I’m naturally parsimonious, obsessive about keeping things going for as long as possible and recycling them responsibly when they reach their end of life.

It’s one reason why I’ve gotten involved in the Repair Café movement. I volunteer for our local branch, which started up in February, on the admin and publicity side of things. The old-fashioned, make-do-and-mend ethos appeals to me. It’s the same spirit evoked in the lyrics of American singer-songwriter Mark Erelli’s “Analog Hero”:

He’s the fix-it man, the fix-it man

If he can’t put it back together, then it was never worth a damn

Maybe he’s crazy for trying to save what’s already gone

Now it ain’t even broken and we’re going for the upgrade

Nobody thinks twice ’bout what we’re really throwing away

It’s out with the old, in with the new…

I can imagine Wendell Berry still pecking out his words on a typewriter on his Kentucky farm. He’s an analogue hero, too. And he doesn’t go nearly as far as Mark Boyle, whose radical life experiment is recounted in The Way Home: Tales from a life without technology, which I reviewed for Shiny New Books in 2019.

I have pretty much made my peace with owning a smartphone. I have few apps and am still more likely to work at my PC or on paper. I’ll concede that I enjoy being able to post to X or Instagram wherever I am, and to keep up with messages on the go. (I used to have to say cryptic things to friends like, “once I leave the house, I will be unavailable except by text.”) Mostly, I’m relieved to have shed the frustrations of outmoded tech. Though I still keep my Nokia brick by my bedside as a trusty alarm clock – and a torch for when the cat wakes me between 2 and 5 each morning.

Ultimately, I feel, a smartphone is a tool like any other. It’s how you use it. Salman Rushdie comes to much the same conclusion about the would-be murder weapon wielded against him: “a knife is a tool, and acquires meaning from the use we make of it. It is morally neutral” (from Knife).

Berry’s argument about overreliance on energy remains a good one, but we are all so complicit in so many ways – even more so than in the late 1980s when he was writing – that avoiding the computer, and now the smartphone, doesn’t seem to hold particular merit. While this pamphlet will be but a quaint curio piece for most readers (rather than a parallel to the battle of wills I’ve conducted with myself), it is engaging and convincing, and the societal issues it considers are still ones to be wrestled with.

My copy was purchased with part of a £30 voucher I received free from Penguin UK for being part of their “Bookmarks” online community – answering polls, surveys, etc.

Love Your Library, June 2023

Thanks, as always, to Elle for her participation, and to Laura and Naomi for their reviews of books borrowed from libraries. Ever since she was our Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award shadow panel winner, I’ve followed Julianne Pachico’s blog. A recent post lists books she currently has from the library. I like her comment that borrowing books “is definitely scratching that dopamine itch for me”! On Instagram I spotted this post celebrating both libraries and Pride Month.

And so to my reading and borrowing since last time.

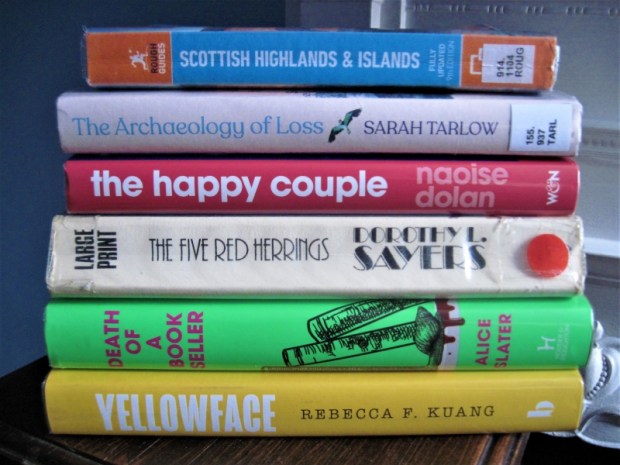

Most of my reservations seemed to come in all at once, right before we left for Scotland, so I’m taking a giant pile along with me (luckily, we’re traveling by car so I don’t have space or weight restrictions) and will see which I can get to, while also fitting in Scotland-themed reads, June review copies, e-books for paid review, and a few of my 20 Books of Summer!

READ

- Rainbow Rainbow: Stories by Lydia Conklin

- The Greengage Summer by Rumer Godden

- Under the Rainbow by Celia Laskey

- Scattered Showers: Stories by Rainbow Rowell

- A Cat in the Window by Derek Tangye

- Cats in Concord by Doreen Tovey

CURRENTLY READING

- The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan

- The Gifts by Liz Hyder

- Milk by Alice Kinsella

- Yellowface by Rebecca F. Kuang

- Music in the Dark by Sally Magnusson

- Five Red Herrings by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Death of a Bookseller by Alice Slater

- The Archaeology of Loss by Sarah Turlow

- The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle by Kirsty Wark

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

RETURNED UNREAD

- Pod by Laline Paull – I wanted to give this a try because it made the Women’s Prize shortlist, but I looked at the first few pages and skimmed through the rest and knew I just couldn’t take it seriously. I mean, look at lines like these: “The Rorqual wanted to laugh, but it was serious. The dolphin had been in some physical horror and had lost his mind. Google could not bear his mistake. The sound he raced toward was not Base, but this thing, this creature, he had never before encountered.”

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

Two Memoirs by Freaks and Geeks Alumni

These days, I watch no television. At all. I haven’t owned a set in over eight years. But as a kid, teen and young adult, I loved TV. I devoured cartoons and reruns every day after school (Pinky and the Brain, I Love Lucy, Gilligan’s Island, The Brady Bunch, etc.); I was a devoted watcher of the TGIF line-up, and petitioned my parents to let me stay up late to watch Murphy Brown. We subscribed to the TV Guide magazine, and each September I would eagerly read through the pilot descriptions with a highlighter, planning which new shows I was going to try. It’s how I found ones like Alias, Felicity, Scrubs and 24 that I followed religiously. Starting in my freshman year of college, I was a mega-fan of American Idol for its first 12 seasons. And so on. Versus now I know nothing about what’s on telly and all the Netflix and box set hits have passed me by.

These days, I watch no television. At all. I haven’t owned a set in over eight years. But as a kid, teen and young adult, I loved TV. I devoured cartoons and reruns every day after school (Pinky and the Brain, I Love Lucy, Gilligan’s Island, The Brady Bunch, etc.); I was a devoted watcher of the TGIF line-up, and petitioned my parents to let me stay up late to watch Murphy Brown. We subscribed to the TV Guide magazine, and each September I would eagerly read through the pilot descriptions with a highlighter, planning which new shows I was going to try. It’s how I found ones like Alias, Felicity, Scrubs and 24 that I followed religiously. Starting in my freshman year of college, I was a mega-fan of American Idol for its first 12 seasons. And so on. Versus now I know nothing about what’s on telly and all the Netflix and box set hits have passed me by.

Ahem. On to the point.

Freaks and Geeks was my favourite show in high school (it aired in 1999–2000, when I was a junior) and the first DVD series I ever owned – a gift from my sister’s boyfriend, who became her first husband. It’s now considered a cult classic, but I can smugly say that I recognized its brilliance from the start. So did critics, but viewers? Not so much, or at least not enough; it was cancelled after just one season. I’ve vaguely followed the main actors’ careers since then, and though I normally don’t read celebrity autobiographies I’ve picked up two by former cast members in the last year. Both:

Yearbook by Seth Rogen (2021)

I have seen a few of Rogen’s (generally really dumb) movies. The fun thing about this autobiographical essay collection is that you can hear his deadpan voice in your head on every line. That there are three F-words within the first three paragraphs of the book tells you what to expect; if you have a problem with a potty mouth, you probably won’t get very far.

I have seen a few of Rogen’s (generally really dumb) movies. The fun thing about this autobiographical essay collection is that you can hear his deadpan voice in your head on every line. That there are three F-words within the first three paragraphs of the book tells you what to expect; if you have a problem with a potty mouth, you probably won’t get very far.

Rogen grew up Jewish in Vancouver in the 1980s and did his first stand-up performance at a lesbian bar at age 13. During his teens he developed an ardent fondness for drugs (mostly pot, but also mushrooms, pills or whatever was going), and a lot of these stories recreate the ridiculous escapades he and his friends went on in search of drugs or while high. My favourite single essay was about a trip to Amsterdam. He also writes about weird encounters with celebrities like George Lucas and Steve Wozniak. A disproportionately long section is devoted to the making of the North Korea farce The Interview, which I haven’t seen.

Seth Rogen speaking at the 2017 San Diego Comic Con International. Photo by Gage Skidmore, from Wikimedia Commons.

Individually, these are all pretty entertaining pieces. But by the end I felt that Rogen had told some funny stories with great dialogue but not actually given readers any insight into his own character; it’s all so much posturing. (Also, I wanted more of the how he got from A to B; like, how does a kid in Canada get cast in a new U.S. TV series?) True, I knew not to expect a sensitive baring of the soul, but when I read a memoir I like to feel I’ve been let in. Instead, the seasoned comedian through and through, Rogen keeps us laughing but at arm’s length.

This Will Only Hurt a Little by Busy Philipps (2018)

I hadn’t kept up with Philipps’s acting, but knew from her Instagram account that she’d gathered a cult following that she spun into modelling and paid promotions, and then a short-lived talk show hosting gig. Although she keeps up a flippant, sarcastic façade for much of the book, there is welcome introspection as she thinks about how women get treated differently in Hollywood. I also got what I wanted from the Rogen but didn’t get: insight into the how of her career, and behind-the-scenes gossip about F&G.

Philipps grew up first in the Chicago outskirts and then mostly in Arizona. She was a headstrong child and her struggle with anxiety started early. When she lost her virginity at age 14, it was actually rape, though she didn’t realize it at the time. At 15, she got pregnant and had an abortion. She developed a habit of seeking validation from men, even if it meant stringing along and cheating on nice guys.

I enjoyed reading about her middle and high school years because she’s just a few years older than me, so the cultural references were familiar (each chapter is named after a different pop song) and I could imagine the scenes – like one at a junior high dance where she got trapped in a mosh pit and dislocated her knee, the first of three times that specific injury happens in the book – taking place in my own middle school auditorium and locker hallway.

I enjoyed reading about her middle and high school years because she’s just a few years older than me, so the cultural references were familiar (each chapter is named after a different pop song) and I could imagine the scenes – like one at a junior high dance where she got trapped in a mosh pit and dislocated her knee, the first of three times that specific injury happens in the book – taking place in my own middle school auditorium and locker hallway.

She never quite made it to the performing arts summer camp she was supposed to attend in upstate New York, but did act in school productions and got an agent and headshots, so that when Mattel came to Scottsdale looking for actresses to play Barbie dolls in her junior year, she was perfectly placed to be cast as a live-action Cher from Clueless. She enrolled in college in Los Angeles (at LMU) but focused more on acting than on classes. After F&G, Dawson’s Creek was her biggest role. It involved moving to Wilmington, North Carolina and introduced her to her best friend, Michelle Williams, but she never felt she fit with the rest of the cast; her impression is that it was very much a star vehicle for Katie Holmes.

Busy Philipps at the Television Critics Association Awards in 2010. Photo by Greg Hernandez, from Wikimedia Commons.

Other projects that get a lot of discussion here are the Will Ferrell ice-skating movie Blades of Glory, which was her joint idea with her high school boyfriend Craig, and had a script written with him and his brother Jeff – there was big drama when they tried to take away her writing credit; and Cougar Town (with Courteney Cox), for which she won the inaugural Television Critics’ Choice Award. She auditioned a lot, including for TV pilots each year, but roles were few and far between, and she got rejected based on her size (when carrying baby weight after her daughters’ births, or once being cast as “the overweight friend”).

Anyway, I was here for the dish on Freaks and Geeks, and it’s juicy, especially about James Franco, who was her character Kim Kelly’s love interest on the show. Kim and Daniel had an on-again, off-again relationship, and the tension between them on camera reflected real life.

“Franco had come back from our few months off and was clearly set on being a VERY SERIOUS ACTOR … [he] had decided that the only way to be taken seriously was to be a fucking prick. Once we started shooting the series, he was not cool to me, at all. Everything was about him, always. His character’s motivation, his choices, his props, his hair, his wardrobe. Basically, he fucking bullied me. Which is what happens a lot on sets. Most of the time, the men who do this get away with it, and most of the time they’re rewarded.”

At one point, he pushed her over on the set; the directors slapped him on the wrist and made him apologize, but she knew nothing was going to come of it. Still, it was her big break:

what we were doing was totally different from the unrealistic teen shows every other network was putting out.

I didn’t know it then, but getting the call about was the first of many you-got-it calls I would get over the course of my career.

when [her daughter] Birdie turns thirteen, I’m going to watch the entire series with her.

And as a P.S., “Seth Rogen was cast as a guest star on [Dawson’s Creek] and he came out and did an episode with me, which was fun. He and Judd had brought me back to L.A. to do two episodes of Undeclared” & she was cast on one season of ER with Linda Cardellini.

The reason I don’t generally read celebrity autobiographies is that the writing simply isn’t strong enough. While Philipps conveys her voice and personality through her style (cursing, capital letters, cynical jokes), some of the storytelling is thin. I mean, there’s not really a chapter’s worth of material in an anecdote about her wandering off when she was two years old. And I think she overeggs it when she insists she’s always gone out and gotten what she wants; the number of rejections she’s racked up says otherwise. I did appreciate the #MeToo feminist perspective, though, looking back to her upbringing and the Harvey Weinsteins of the Hollywood world and forward to how she hopes things will be different for her daughters. I also admired her honesty about her mental health. But I wouldn’t really recommend this unless you are a devoted fan.

I loved these Freaks and Geeks-themed Valentines that a fan posted to Judd Apatow on Twitter this past February.

Filling One Last Bookcase

Earlier this week I inherited a beautiful antique bookcase from an online friend* who, we learned only recently, lived just 20 minutes away. She has to shed some furniture to move to London, and very kindly thought of me. This is the last major item we could possibly fit in our house, but I was happy to accept because it’s so much nicer than any of our Ikea shelving units. It has the kind of mahogany detail that looks like it could belong on a ship’s wheel.

My goals for the extra shelving space were to be able to keep genres together, to eliminate double stacking where possible, to put all books out on display instead of having some away in an overflow crate, and perhaps to free up the tops of a couple units for knick knacks, etc.

It was a multi-step process undertaken with military precision. Can you tell I used to work in a library?

- Reincorporate Short Stories into General Fiction

- Double-stack the already-read Fiction in the bedroom, leaving the more presentable books at the front; create a Signed Copies area

- Move Poetry in with Classics, double-stacking and putting some books on their sides to make more space; create a Classics priority area, with one book per month chosen for the rest of 2018

- Move oversize Science and Nature, Graphic Novels, Children’s Books, and Coffee Table Books (which, because they’re buried under magazines and newspapers on the coffee table shelf, we never look at) onto the bottom shelf of the new bookcase

- Move all Life Writing (biographies/memoirs), which had been split across a few rooms, onto one bookcase in my study

- Add a selection of Travel and Literary Reference to fill the built-in shelves of my desk, joining Reference and Humor

- Integrate Science and Nature, previously kept separate, into one bookcase

Unread fiction is mostly on the hall bookcase, with an area on the bottom shelf for upcoming projects so I can see what’s awaiting me. I’m keeping these in rough date order from left to right: bibliotherapy prescriptions, possibilities for Reading Ireland month, novellas for November, etc.

However, there are a handful of annoying hardback and trade paperback novels that are just that little bit too tall to fit here, so these have formed a partial shelf on the antique case. I’ve also set aside there the book(s) that I think might be included in my Best of 2018 list and a growing stash of Wellcome Book Prize 2019 hopefuls.

You would never believe it, but I think I need more books! Good thing we have a trip planned to Wigtown, Scotland’s Book Town, for the first week of April. In any case, it’s better to have room to grow into than to already be at capacity or overfull. I can always reshuffle as time goes on if I decide I don’t want any double stacking upstairs or if we ever manage to bring back more of my library from America.

From Book Riot I got the idea of making a personal “hold shelf” of books you own and have been meaning to read. So far I only have four books set aside, arranged as a sort of buffet atop the hall bookcase. Perhaps later I’ll replace this with a full shelf on the antique bookcase. Other ideas for the empty space there would be showcasing my most presentable fiction, or creating a favorites shelf. This was suggested by Paul and corroborated by The Novel Cure, which suggests pulling out the 10 books you love most and are likely to turn to for inspiration.

*If you’re on Instagram, you must check her out. She is a #bookstagram pro: @beth.bonini.

How do you organize your bookshelves?

Seeking Advice about Instagram

I recently signed up to Instagram – bookishbeck, as always, if you want to connect – but haven’t been very active on the site yet. (My sister coerced me into joining, mostly so I could follow itsdougthepug.) The main issue is that I don’t have a smartphone, so rather than using the app version I have to go via a program called Gramblr and can’t access all the usual features. A lot of the time it can seem like too much of a faff to post pictures on there.

However, I want to give the site a proper go so would like to get advice on how I can best use it as a book blogger. I know it can be a good way to connect with publishers by posting photos of review copies they’ve sent you and linking to your reviews, etc. I’ve already followed a bunch of publishers, but I know there’s more I could and should be doing.

So I’ll turn it over to you: those of you who use Instagram (primarily for bookish reasons rather than personal photos, though that’s cool too), what accounts should I be following? What’s your strategy when posting book photos? How can I use hashtags and captions to my advantage? Do you use Instagram in pretty much the same way as you do Twitter, or are there subtle differences I should be aware of?

This was a hit and miss collection for me: I only loved one of the stories, and enjoyed another three; touches of magic realism à la Aimee Bender produce the two weakest stories, and there are a few that simply tail off without having made a point. My favorite was “Many a Little Makes,” about a trio of childhood best friends whose silly sleepover days come to an end as they develop separate interests and one girl sleeps with another one’s brother. In “Tell Me My Name,” set in a post-economic collapse California, an actress who was a gay icon back in New York City pitches a TV show to the narrator’s wife, who makes kids’ shows.

This was a hit and miss collection for me: I only loved one of the stories, and enjoyed another three; touches of magic realism à la Aimee Bender produce the two weakest stories, and there are a few that simply tail off without having made a point. My favorite was “Many a Little Makes,” about a trio of childhood best friends whose silly sleepover days come to an end as they develop separate interests and one girl sleeps with another one’s brother. In “Tell Me My Name,” set in a post-economic collapse California, an actress who was a gay icon back in New York City pitches a TV show to the narrator’s wife, who makes kids’ shows.

Parsons’s debut collection, longlisted for the U.S. National Book Award in 2019, contains a dozen gritty stories set in or remembering her native Texas. Eleven of the 12 are in the first person, with the mostly female narrators unnamed or underdeveloped and thus difficult to differentiate from each other. The homogeneity of voice and recurring themes – drug use, dysfunctional families, overweight bodies, lesbian or lopsided relationships – lead to monotony.

Parsons’s debut collection, longlisted for the U.S. National Book Award in 2019, contains a dozen gritty stories set in or remembering her native Texas. Eleven of the 12 are in the first person, with the mostly female narrators unnamed or underdeveloped and thus difficult to differentiate from each other. The homogeneity of voice and recurring themes – drug use, dysfunctional families, overweight bodies, lesbian or lopsided relationships – lead to monotony.

Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of

Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of  A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life.

A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life. Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via

Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via

This was my first taste of Baldwin’s fiction, and it was very good indeed. David, a penniless American, came to Paris to find himself. His second year there he meets Giovanni, an Italian barman. They fall in love and move in together. There’s a problem, though: David has a fiancée – Hella, who’s traveling in Spain. It seems that David had bisexual tendencies but went off women after Giovanni. “Much has been written of love turning to hatred, of the heart growing cold with the death of love.” We know from the first pages that David has fled to the south of France and Giovanni faces the guillotine in the morning, but all through Baldwin maintains the tension as we wait to hear why he is sentenced to death. Deeply sad, but also powerful and brave. I’ll make Go Tell It on the Mountain my next one by Baldwin.

This was my first taste of Baldwin’s fiction, and it was very good indeed. David, a penniless American, came to Paris to find himself. His second year there he meets Giovanni, an Italian barman. They fall in love and move in together. There’s a problem, though: David has a fiancée – Hella, who’s traveling in Spain. It seems that David had bisexual tendencies but went off women after Giovanni. “Much has been written of love turning to hatred, of the heart growing cold with the death of love.” We know from the first pages that David has fled to the south of France and Giovanni faces the guillotine in the morning, but all through Baldwin maintains the tension as we wait to hear why he is sentenced to death. Deeply sad, but also powerful and brave. I’ll make Go Tell It on the Mountain my next one by Baldwin.  Garfield, Why Do You Hate Mondays? by Jim Davis (1982)

Garfield, Why Do You Hate Mondays? by Jim Davis (1982)

This is a collected comic strip that appeared on Instagram between 2016 and 2018 (you can view it in full

This is a collected comic strip that appeared on Instagram between 2016 and 2018 (you can view it in full

I was curious about this bestselling fable, but wish I’d left it to its 1970s oblivion. The title seagull stands out from the flock for his desire to fly higher and faster than seen before. He’s not content to be like all the rest; once he arrives in birdie heaven he starts teaching other gulls how to live out their perfect freedom. “We can lift ourselves out of ignorance, we can find ourselves as creatures of excellence and intelligence and skill.” Gradually comes the sinking realization that JLS is a Messiah figure. I repeat, the seagull is Jesus. (“They are saying in the Flock that if you are not the Son of the Great Gull Himself … then you are a thousand years ahead of your time.”) An obvious allegory, unlikely dialogue, dated metaphors (“like a streamlined feathered computer”), cringe-worthy New Age sentiments and loads of poor-quality soft-focus photographs: This was utterly atrocious.

I was curious about this bestselling fable, but wish I’d left it to its 1970s oblivion. The title seagull stands out from the flock for his desire to fly higher and faster than seen before. He’s not content to be like all the rest; once he arrives in birdie heaven he starts teaching other gulls how to live out their perfect freedom. “We can lift ourselves out of ignorance, we can find ourselves as creatures of excellence and intelligence and skill.” Gradually comes the sinking realization that JLS is a Messiah figure. I repeat, the seagull is Jesus. (“They are saying in the Flock that if you are not the Son of the Great Gull Himself … then you are a thousand years ahead of your time.”) An obvious allegory, unlikely dialogue, dated metaphors (“like a streamlined feathered computer”), cringe-worthy New Age sentiments and loads of poor-quality soft-focus photographs: This was utterly atrocious.

In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. He’s so jaded that he barely listens to his patients anymore. “Was I just lazy, or was I genuinely so arrogant that I’d become bored by other people’s misery?” he asks himself. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy: learning that his longtime secretary’s husband has terminal cancer and visiting the man for some straight talk about death; discovering that the neighbor he’s never met, but only known via piano playing through the wall, is deaf, and striking up a friendship with him; and meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm, and vowing to get to the bottom of her trauma. This debut novel by a psychologist (and table tennis champion) is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.

In late-1940s Paris, a psychiatrist counts down the days and appointments until his retirement. He’s so jaded that he barely listens to his patients anymore. “Was I just lazy, or was I genuinely so arrogant that I’d become bored by other people’s misery?” he asks himself. A few experiences awaken him from his apathy: learning that his longtime secretary’s husband has terminal cancer and visiting the man for some straight talk about death; discovering that the neighbor he’s never met, but only known via piano playing through the wall, is deaf, and striking up a friendship with him; and meeting Agatha, a new German patient with a history of self-harm, and vowing to get to the bottom of her trauma. This debut novel by a psychologist (and table tennis champion) is a touching, subtle and gently funny story of rediscovering one’s purpose late in life.  Daniel is a recently widowed farmer in rural Wales. On his own for the challenges of lambing, he hates who he’s become. “She would not have liked this anger in me. I was not an angry man.” In the meantime, a badger-baiter worries the police are getting wise to his nocturnal misdemeanors and looks for a new, remote locale to dig for badgers. I kept waiting for these two story lines to meet explosively, but instead they just fizzle out. I should have been prepared for the animal cruelty I’d encounter here, but it still bothered me. Even the descriptions of lambing, and of Daniel’s wife’s death, are brutal. Jones’s writing reminded me of Andrew Michael Hurley’s; while I did appreciate the observation that violence begets more violence in groups of men (“It was the gangness of it”), this was a tough read for me.

Daniel is a recently widowed farmer in rural Wales. On his own for the challenges of lambing, he hates who he’s become. “She would not have liked this anger in me. I was not an angry man.” In the meantime, a badger-baiter worries the police are getting wise to his nocturnal misdemeanors and looks for a new, remote locale to dig for badgers. I kept waiting for these two story lines to meet explosively, but instead they just fizzle out. I should have been prepared for the animal cruelty I’d encounter here, but it still bothered me. Even the descriptions of lambing, and of Daniel’s wife’s death, are brutal. Jones’s writing reminded me of Andrew Michael Hurley’s; while I did appreciate the observation that violence begets more violence in groups of men (“It was the gangness of it”), this was a tough read for me.  This seems destined to be in many a bibliophile’s Christmas stocking this year. It’s a collection of mini-essays, quotations and listicles on topics such as DNFing, merging your book collection with a new partner’s, famous bibliophiles and bookshelves from history, and how you choose to organize your library. It’s full of fun trivia. Two of my favorite factoids: Bill Clinton keeps track of his books via a computerized database, and the original title of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was “I Have Committed Fornication but that Was in Another Country” (really?!). It’s scattered and shallow, but fun in the same way that Book Riot articles generally are. (I almost always click through to 2–5 articles in my Book Riot e-newsletters, so that’s no problem in my book.) I couldn’t find a single piece of information on ‘Annie Austen’, not even a photo – I sincerely doubt she’s that Kansas City lifestyle blogger, for instance – so I suspect she’s actually a collective of interns.

This seems destined to be in many a bibliophile’s Christmas stocking this year. It’s a collection of mini-essays, quotations and listicles on topics such as DNFing, merging your book collection with a new partner’s, famous bibliophiles and bookshelves from history, and how you choose to organize your library. It’s full of fun trivia. Two of my favorite factoids: Bill Clinton keeps track of his books via a computerized database, and the original title of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was “I Have Committed Fornication but that Was in Another Country” (really?!). It’s scattered and shallow, but fun in the same way that Book Riot articles generally are. (I almost always click through to 2–5 articles in my Book Riot e-newsletters, so that’s no problem in my book.) I couldn’t find a single piece of information on ‘Annie Austen’, not even a photo – I sincerely doubt she’s that Kansas City lifestyle blogger, for instance – so I suspect she’s actually a collective of interns.

This posthumous collection brings together essays Broyard wrote for the New York Times after being diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer in 1989, journal entries, a piece he’d written after his father’s death from bladder cancer in 1954, and essays from the early 1980s about “the literature of death.” He writes to impose a narrative on his illness, expatiating on what he expects of his doctor and how he plans to live with style even as he’s dying. “If you have to die, and I hope you don’t, I think you should try to die the most beautiful death you can,” he charmingly suggests. It’s ironic that he laments a dearth of literature (apart from Susan Sontag) about illness and dying – if only he could have seen the flourishing of cancer memoirs in the last two decades! [An interesting footnote: in 2007 Broyard’s daughter Bliss published a memoir, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets, about finding out that her father was in fact black but had passed as white his whole life. I’ll be keen to read that.]

This posthumous collection brings together essays Broyard wrote for the New York Times after being diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer in 1989, journal entries, a piece he’d written after his father’s death from bladder cancer in 1954, and essays from the early 1980s about “the literature of death.” He writes to impose a narrative on his illness, expatiating on what he expects of his doctor and how he plans to live with style even as he’s dying. “If you have to die, and I hope you don’t, I think you should try to die the most beautiful death you can,” he charmingly suggests. It’s ironic that he laments a dearth of literature (apart from Susan Sontag) about illness and dying – if only he could have seen the flourishing of cancer memoirs in the last two decades! [An interesting footnote: in 2007 Broyard’s daughter Bliss published a memoir, One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets, about finding out that her father was in fact black but had passed as white his whole life. I’ll be keen to read that.]  This was a random 50p find at the Hay-on-Wye market on our last trip. In July 1940 Kipps adopted a house sparrow that had fallen out of the nest – or, perhaps, been thrown out for having a deformed wing and foot. Clarence became her beloved pet, living for just over 12 years until dying of old age. A former professional musician, Kipps served as an air-raid warden during the war; she and Clarence had a couple of close shaves and had to evacuate London at one point. Clarence sang more beautifully than the average sparrow and could do a card trick and play dead. He loved to nestle inside Kipps’s blouse and join her for naps under the duvet. At age 11 he had a stroke, but vet attention (and champagne) kept him going for another year, though with less vitality. This is sweet but not saccharine, and holds interest for its window onto domesticated birds’ behavior. With photos, and a foreword by Julian Huxley.

This was a random 50p find at the Hay-on-Wye market on our last trip. In July 1940 Kipps adopted a house sparrow that had fallen out of the nest – or, perhaps, been thrown out for having a deformed wing and foot. Clarence became her beloved pet, living for just over 12 years until dying of old age. A former professional musician, Kipps served as an air-raid warden during the war; she and Clarence had a couple of close shaves and had to evacuate London at one point. Clarence sang more beautifully than the average sparrow and could do a card trick and play dead. He loved to nestle inside Kipps’s blouse and join her for naps under the duvet. At age 11 he had a stroke, but vet attention (and champagne) kept him going for another year, though with less vitality. This is sweet but not saccharine, and holds interest for its window onto domesticated birds’ behavior. With photos, and a foreword by Julian Huxley.

Mayne was vicar at the university church in Cambridge when he came down with a mysterious, debilitating illness, only later diagnosed as myalgic encephalomyelitis or post-viral fatigue syndrome. During his illness he was offered the job of Dean of Westminster, and accepted the post even though he worried about his ability to carry out his duties. He writes of his frustration at not getting better and receiving no answers from doctors, but much of this short memoir is – unsurprisingly, I suppose – given over to theological musings on the nature of suffering, with lots of quotations (too many) from theologians and poets. Curiously, he also uses Broyard’s word, speaking of the “intoxication of convalescence.”

Mayne was vicar at the university church in Cambridge when he came down with a mysterious, debilitating illness, only later diagnosed as myalgic encephalomyelitis or post-viral fatigue syndrome. During his illness he was offered the job of Dean of Westminster, and accepted the post even though he worried about his ability to carry out his duties. He writes of his frustration at not getting better and receiving no answers from doctors, but much of this short memoir is – unsurprisingly, I suppose – given over to theological musings on the nature of suffering, with lots of quotations (too many) from theologians and poets. Curiously, he also uses Broyard’s word, speaking of the “intoxication of convalescence.”  The author has a PhD in religion and art and produced sculptures for a Benedictine abbey in British Columbia and the Peace Museum in Hiroshima. I worried this would be too New Agey for me, but at 20p from a closing-down charity shop, it was worth taking a chance on. Nerburn feels we are often too “busy with our daily obligations … to surround our hearts with the quiet that is necessary to hear life’s softer songs.” He tells pleasant stories of moments when he stopped to appreciate meaning and connection, like watching a man in a wheelchair fly a kite, setting aside his to-do list to have coffee with an ailing friend, and attending the funeral of a Native American man he once taught.

The author has a PhD in religion and art and produced sculptures for a Benedictine abbey in British Columbia and the Peace Museum in Hiroshima. I worried this would be too New Agey for me, but at 20p from a closing-down charity shop, it was worth taking a chance on. Nerburn feels we are often too “busy with our daily obligations … to surround our hearts with the quiet that is necessary to hear life’s softer songs.” He tells pleasant stories of moments when he stopped to appreciate meaning and connection, like watching a man in a wheelchair fly a kite, setting aside his to-do list to have coffee with an ailing friend, and attending the funeral of a Native American man he once taught.