Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Writers’ Prize & Young Writer of the Year Award Catch-Up

This time of year, it’s hard to keep up with all of the literary prize announcements: longlists, shortlists, winners. I’m mostly focussing on the Carol Shields Prize for Fiction this year, but I like to dip a toe into the others where I can. I ask: What do I have time to read? What can I find at the library? and Which books are on multiple lists so I can tick off several at a go??

Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction

(Shortlist to be announced on 27 March.)

Read so far: Intervals by Marianne Brooker, Matrescence by Lucy Jones

&

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud

Past: Sunday Times/Charlotte Aitken Young Writer of the Year Award shortlist

Currently: Jhalak Prize longlist

I also expect this to be a strong contender for the Wainwright Prize for nature writing, and hope it doesn’t end up being a multi-prize bridesmaid as it is an excellent book but an unusual one that is hard to pin down by genre. Most simply, it is a travel memoir taking in flat landscapes of the British Isles: the Cambridgeshire fens, Orford Ness in Suffolk, Morecambe Bay, Newcastle Moor, and the Orkney Islands.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

But flatness is a psychological motif as well as a physical reality here. Growing up in Pakistan with a violent Pakistani father and a passive Scottish mother, Masud chose the “freeze” option when in fight-or-flight situations. When she was 15, her father disowned her and she moved with her mother and sisters to Scotland. Though no particularly awful things happened, a childhood lack of safety, belonging and love left her with complex PTSD that still affects how she relates to her body and to other people, even after her father’s death.

Masud is clear-eyed about her self and gains a new understanding of what her mother went through during their trip to Orkney. The Newcastle chapter explores lockdown as a literal Covid-era circumstance but also as a state of mind – the enforced solitude and stillness suited her just fine. Her descriptions of landscapes and journeys are engaging and her metaphors are vibrant: “South Nuns Moor stretched wide, like mint in my throat”; “I couldn’t stop thinking about the Holm of Grimbister, floating like a communion wafer on the blue water.” Although she is an academic, her language is never off-puttingly scholarly. There is a political message here about the fundamental trauma of colonialism and its ongoing effects on people of colour. “I don’t want ever to be wholly relaxed, wholly at home, in a world of flowing fresh water built on the parched pain of others,” she writes.

What initially seems like a flat authorial affect softens through the book as Masud learns strategies for relating to her past. “All families are cults. All parents let their children down.” Geography, history and social justice are all a backdrop for a stirring personal story. Literally my only annoyance was the pseudonyms she gives to her sisters (Rabbit, Spot and Forget-Me-Not). (Read via Edelweiss) ![]()

And a quick skim:

Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World by Naomi Klein

Past: Writers’ Prize shortlist, nonfiction category

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library)

For years people have been confusing Naomi Klein (geography professor, climate commentator, author of No Logo, etc.) with Naomi Wolf (feminist author of The Beauty Myth, Vagina, etc.). This became problematic when “Other Naomi” espoused various right-wing conspiracy theories, culminating with allying herself with Steve Bannon in antivaxxer propaganda. Klein theorizes on Wolf’s ideological journey and motivations, weaving in information about the doppelganger in popular culture (e.g., Philip Roth’s novels) and her own concerns about personal branding. I’m not politically minded enough to stay engaged with this but what I did read I found interesting and shrewdly written. I do wonder how her publisher was confident this wouldn’t attract libel allegations? (Public library) ![]()

Predictions: Cumming (see below) and Klein are very likely to advance. I’m less drawn to the history or popular science/tech titles. I’d most like to read Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista, Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder, and How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair. I’d be delighted for Brooker, Jones and Masud to be on the shortlist. Three or more by BIPOC would seem appropriate. I expect they’ll go for diversity of subject matter as well.

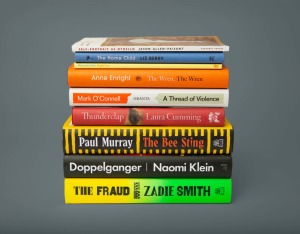

Writers’ Prize

Last year I read most books from the shortlists and so was able to make informed (and, amazingly, thoroughly correct) predictions of the winners. I didn’t do as well this year. In particular, I failed with the nonfiction list in that I DNFed Mark O’Connell’s book and twice borrowed the Cumming from the library but never managed to make myself start it; I thought her On Chapel Sands overrated. (I did skim the Klein, as above.) But at least I read the poetry shortlist in full:

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library)

Self-Portrait as Othello by Jason Allen-Paisant: I found more to sink my teeth into here than I did with his debut collection, Thinking with Trees (2021). Part I’s childhood memories of Jamaica open out into a wider world as the poet travels to London, Paris and Venice, working in snippets of French and Italian and engaging with art and literature. “I’m haunted as much by the character Othello as by the silences in the story.” Part III returns home for the death of his grandmother and a coming to terms with identity. [Winner: Forward Prize for Best Collection; Past: T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist] (Public library) ![]()

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library)

The Home Child by Liz Berry: A novel in verse “loosely inspired,” as Berry puts it, by her great-aunt Eliza Showell’s experience: she was a 12-year-old orphan when, in 1908, she was forcibly migrated from the English Midlands to Nova Scotia. The scenes follow her from her home to the Children’s Emigration Home in Birmingham, on the sea voyage, and in her new situation as a maid to an elderly invalid. Life is gruelling and lonely until a boy named Daniel also comes to the McPhail farm. This was a slow and not especially engaging read because of the use of dialect, which for me really got in the way of the story. (Public library) ![]()

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist)

& Bright Fear by Mary Jean Chan (Current: Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist) ![]()

Three category winners:

- The Wren, The Wren by Anne Enright (Fiction)

- Thunderclap by Laura Cumming (Nonfiction) (Current: Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction longlist)

- The Home Child by Liz Berry (Poetry)

Overall winner: The Home Child by Liz Berry

Observations: The academy values books that cross genres. It appreciates when authors try something new, or use language in interesting ways (e.g. dialect – there’s also some in the Allen-Paisant, but not as much as in the Berry). But my taste rarely aligns with theirs, such that I am unlikely to agree with its judgements. Based on my reading, I would have given the category awards to Murray, Klein and Chan and the overall award perhaps to Murray. (He recently won the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize instead.)

World Poetry Day stack last week

Young Writer of the Year Award

Shortlist:

- The New Life by Tom Crewe

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction)

(Past: Nero Book Award shortlist, debut fiction) - Close to Home by Michael Magee (Winner: Nero Book Award, debut fiction category)

- A Flat Place by Noreen Masud (see above)

&

Bad Diaspora Poems by Momtaza Mehri

Winner: Forward Prize for Best First Collection

Nostalgia is bidirectional. Vantage point makes all the difference. Africa becomes a repository of unceasing fantasies, the sublimation of our curdled angst.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut.

Crossing between Somalia, Italy and London and proceeding from the 1830s to the present day, this debut collection sets family history amid wider global movements. It’s peopled with nomads, colonisers, immigrants and refugees. In stanzas and prose paragraphs, wordplay and truth-telling, Mehri captures the welter of emotions for those whose identity is split between countries and complicated by conflict and migration. I particularly admired “Wink Wink,” which is presented in two columns and opens with the suspension of time before the speaker knew their father was safe after a terrorist attack. There’s super-clever enjambment in this one: “this time it happened / after evening prayer // cascade of iced tea / & sugared straws // then a line / break // hot spray of bullets & / reverb & // in less than thirty minutes we / they the land // lose twenty of our children”. Confident and sophisticated, this is a first-rate debut. ![]()

A few more favourite lines:

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one dies on the journey, something always does.

(from “A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True”)

You think of how casually our bodies are overruled by kin,

by blood, by heartaches disguised as homelands.

How you can count the years you have lived for yourself on one hand.

History is the hammer. You are the nail.

(from “Reciprocity is a Two-way Street”)

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

I hadn’t been following the Award on Instagram so totally missed the news of them bringing back a shadow panel for the first time since 2020. The four young female Bookstagrammers chose Mehri’s collection as their winner – well deserved.

Winner: The New Life by Tom Crewe

This was no surprise given that it was the Sunday Times book of the year last year (and my book of the year, to be fair). I’ve had no interest in reading the Magee. It’s a shame that a young woman of colour did not win as this year would have been a good opportunity for it. (What happened last year, seriously?!) But in that this award is supposed to be tied into the zeitgeist and honour an author on their way up in the world – as with Sally Rooney in my shadowing year – I do think the judges got it right.

Something a bit different that still fit my September short stories focus: these nine linked fairytales feature sentient animals and fantastical creatures learning relatable life lessons. In the title story, Squishbod airs his closet once a year, which requires taking out the skeleton – a symbol of shameful secrets one holds close. Newfound friendship shades into obsession in “The Sea Wolf and the Hare” before the hare’s epiphany that love requires freedom. Characters wrestle with greed, fear and feelings of inadequacy or incompleteness. In “The End of the World,” which can be interpreted as a subtle climate fable, a thick fog induces panic. A puffin entertains thoughts of piracy. Spendthrift is compelled to have the latest in home décor while Mousekin frets over his lack of ambition. This is perfect for Moomins fans, who will embrace the blend of domesticity and adventure, melancholy and reassurance. I was also reminded of another European children’s novel-in-stories I’ve reviewed,

Something a bit different that still fit my September short stories focus: these nine linked fairytales feature sentient animals and fantastical creatures learning relatable life lessons. In the title story, Squishbod airs his closet once a year, which requires taking out the skeleton – a symbol of shameful secrets one holds close. Newfound friendship shades into obsession in “The Sea Wolf and the Hare” before the hare’s epiphany that love requires freedom. Characters wrestle with greed, fear and feelings of inadequacy or incompleteness. In “The End of the World,” which can be interpreted as a subtle climate fable, a thick fog induces panic. A puffin entertains thoughts of piracy. Spendthrift is compelled to have the latest in home décor while Mousekin frets over his lack of ambition. This is perfect for Moomins fans, who will embrace the blend of domesticity and adventure, melancholy and reassurance. I was also reminded of another European children’s novel-in-stories I’ve reviewed,  The title is adapted from Audre Lorde’s term for Zami, “biomythography” (Kim Coleman Foote also borrowed it for

The title is adapted from Audre Lorde’s term for Zami, “biomythography” (Kim Coleman Foote also borrowed it for

Fubini is the CEO of Natoora, which supplies produce to world-class restaurants. He is passionate about restoring seasonal patterns of eating; just because we can purchase strawberries year-round doesn’t mean we should. Supermarkets (which control 85% or more of food stock in the USA and UK) are to blame, Fubini explains, because after the Second World War they “tricked families with feelings of value and convenience, yet what they really wanted was for them to consume more of this unhealthy, flavour-engineered food [i.e. ultra-processed foods], which is cheap to produce and easy to transport because of its industrial nature.” He gives a few examples of fruits that have been selected for flavour rather than shelf life, such as the winter tomato varieties he popularized via River Café, green citrus, and the divine Greta white peach that set him off on this journey in 2011. This is a concise and readable introduction to modern food issues.

Fubini is the CEO of Natoora, which supplies produce to world-class restaurants. He is passionate about restoring seasonal patterns of eating; just because we can purchase strawberries year-round doesn’t mean we should. Supermarkets (which control 85% or more of food stock in the USA and UK) are to blame, Fubini explains, because after the Second World War they “tricked families with feelings of value and convenience, yet what they really wanted was for them to consume more of this unhealthy, flavour-engineered food [i.e. ultra-processed foods], which is cheap to produce and easy to transport because of its industrial nature.” He gives a few examples of fruits that have been selected for flavour rather than shelf life, such as the winter tomato varieties he popularized via River Café, green citrus, and the divine Greta white peach that set him off on this journey in 2011. This is a concise and readable introduction to modern food issues. Antrobus, a British-Jamaican poet, won the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Ted Hughes Award, and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for his first collection,

Antrobus, a British-Jamaican poet, won the Rathbones Folio Prize, the Ted Hughes Award, and the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award for his first collection,  There’s a prophetic tone behind poems about animal casualties due to pesticides, with “We were warned” used as a refrain in “1 Zephaniah”:

There’s a prophetic tone behind poems about animal casualties due to pesticides, with “We were warned” used as a refrain in “1 Zephaniah”: There is some inconsistency in terms of the amount of context and interpretation given, however. For some poets, there may be just a line or two of text, followed by a reprinted poem (Richard Wilbur, Les Murray); for others, there are paragraphs’ worth of explanations, interspersed with excerpts (Andrew Marvell, Thomas Gray). Some choices are obvious; others are deliberately obscure (e.g., eschewing Robert Frost’s and Philip Larkin’s better-known poems in favour of “Out, Out” and “The Explosion”). The diversity is fairly low, and you can see Carey’s age in some of his introductions: “Edward Lear was gay, and felt a little sad when friends got married”; “Alfred Edward Housman was gay, and he thought it unjust that he should be made to feel guilty about something that was part of his nature.” There’s way too much First and Second World War poetry here. And can a poet really be one of the 100 greatest ever when I’ve never heard of them? (May Wedderburn Cannan, anyone?)

There is some inconsistency in terms of the amount of context and interpretation given, however. For some poets, there may be just a line or two of text, followed by a reprinted poem (Richard Wilbur, Les Murray); for others, there are paragraphs’ worth of explanations, interspersed with excerpts (Andrew Marvell, Thomas Gray). Some choices are obvious; others are deliberately obscure (e.g., eschewing Robert Frost’s and Philip Larkin’s better-known poems in favour of “Out, Out” and “The Explosion”). The diversity is fairly low, and you can see Carey’s age in some of his introductions: “Edward Lear was gay, and felt a little sad when friends got married”; “Alfred Edward Housman was gay, and he thought it unjust that he should be made to feel guilty about something that was part of his nature.” There’s way too much First and Second World War poetry here. And can a poet really be one of the 100 greatest ever when I’ve never heard of them? (May Wedderburn Cannan, anyone?) In her bittersweet second memoir, a religion professor finds the joys and ironies in a life overshadowed by advanced cancer.

In her bittersweet second memoir, a religion professor finds the joys and ironies in a life overshadowed by advanced cancer. This story hit all too close to home to me: like Kat Lister, my sister was widowed in her thirties, her husband having endured gruelling years of treatment for brain cancer that caused seizures and memory loss. Lister’s husband,

This story hit all too close to home to me: like Kat Lister, my sister was widowed in her thirties, her husband having endured gruelling years of treatment for brain cancer that caused seizures and memory loss. Lister’s husband,  Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation:

Allen-Paisant, from Jamaica and now based in Leeds, describes walking in the forest as an act of “reclamation.” For people of colour whose ancestors were perhaps sent on forced marches, hiking may seem strange, purposeless (the subject of “Black Walking”). Back in Jamaica, the forest was a place of utility rather than recreation: The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The emotional scope of the poems is broad: the author fondly remembers his brick-making ancestors and his honeymoon; he sombrely imagines the last moments of an old man dying in a hospital; he expresses guilt over accidentally dismembering an ant, yet divulges that he then destroyed the ants’ nest deliberately. There are even a couple of cheeky, carnal poems, one about a couple of teenagers he caught copulating in the street and one, “The Hottest Day of the Year,” about a longing for touch. “Matter,” in ABAB stanzas, is on the theme of racial justice by way of the Black Lives Matter movement. What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort.

What came through particularly clearly for me was the older generation’s determination to not be a burden: living through the Second World War gave them a sense of perspective, such that they mostly did not complain about their physical ailments and did not expect heroic measures to be made to help them. (Her father knew his condition was “becoming too much” to deal with, and Granny Rosie would sometimes say, “I’ve had enough of me.”) In her father’s case, this was because he held out hope of an afterlife. Although Mosse does not share his religious beliefs, she is glad that he had them as a comfort.