10 Favorite Nonfiction Novellas from My Shelves

What do I mean by a nonfiction novella? I’m not claiming a new genre like Truman Capote did for the nonfiction novel (so unless they’re talking about In Cold Blood or something very similar, yes, I can and do judge people who refer to a memoir as a “nonfiction novel”!); I’m referring literally to any works of nonfiction shorter than 200 pages. Many of my selections even come well under 100 pages.

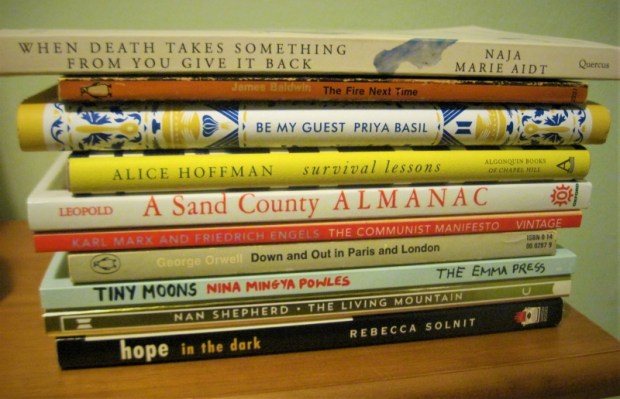

I’m kicking off this nonfiction-focused week of Novellas in November with a rundown of 10 of my favorite short nonfiction works. Maybe you’ll find inspiration by seeing the wide range of subjects covered here: bereavement, social and racial justice, hospitality, cancer, nature, politics, poverty, food and mountaineering. I’d reviewed all but one of them on the blog, half of them as part of Novellas in November in various years.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

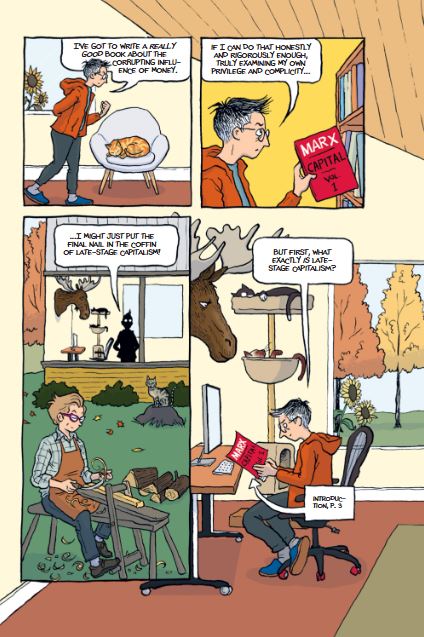

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Any suitably short nonfiction on your shelves?

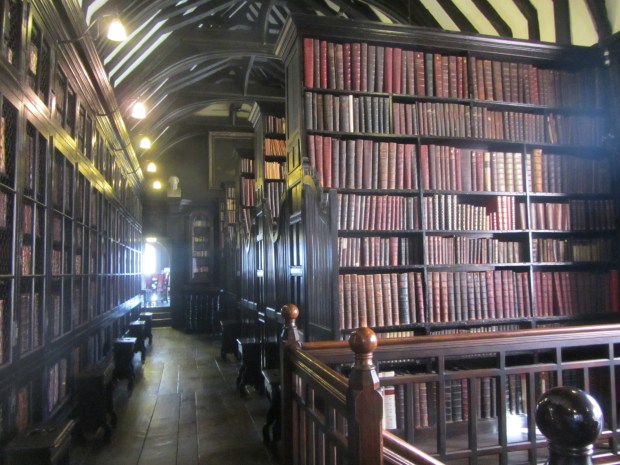

Literary Tourism in Manchester

Over the August bank holiday weekend, my husband and I went to Manchester for the first time. Big cities aren’t our usual vacation destinations of choice, but we were going for the Sufjan Stevens gig at the O2 Apollo on the 31st and wanted to do the city justice while we were there, so stayed two nights at a chain hotel and worked out everything we wanted to see and do there, including two literary pilgrimages for me: Elizabeth Gaskell’s House and Chetham’s Library, where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels met and discussed ideas in the summer of 1845. Armed only with a two-page map sliced out of an eleven-year-old Rough Guide, we felt perhaps a little ill-equipped, but managed to have a nice time nonetheless.

In preparation, I read The Communist Manifesto on the train ride north. It’s only 50 pages, and even with an introduction and multiple prefaces my Vintage Classics copy only comes to 70-some pages. That’s not to say it’s an easy read. I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the thread of the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. In fact, it had never occurred to me that this was first issued in Marx’s native German; like Darwin’s Origin of Species, another seminal Victorian text, it has so many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors that have entered into common discourse that I simply assumed it was composed in English.

After leaving our bags at the hotel on Sunday afternoon, we wandered over to the Gaskell House. It’s only open a few days a week, so we were lucky to be around during its opening hours. All of the house’s contents were sold at auction early in the twentieth century, so none of the furnishings are original, but the current contents have been painstakingly chosen to suggest what the house would have looked like at the time Gaskell and her family – a Unitarian minister husband and their four daughters – lived there. I especially enjoyed seeing William’s study and hearing how Charlotte Brontë hid behind the curtains in the drawing room so she wouldn’t have to socialize with the Gaskells’ visitors. The staff are knowledgeable and unfussy; unlike in your average National Trust house, they let you sit on the furniture and touch the objects. The gardens are also beautifully landscaped.

Talk about a contrast, though: look across the street and you see council housing and rubbish piled up on the pavement. In Gaskell’s time this was probably a genteel suburb, but now it’s an easy walk from the city center and in a considerably down-at-heel area. Indeed, we were taken aback by how grimy parts of Manchester were, and by how many homeless we encountered.

I’ve read four of Gaskell’s books: Mary Barton, North and South, Cranford and The Life of Charlotte Brontë. She’s not one of my favorite Victorian novelists, but I enjoyed each of those and intend to – someday – read Sylvia’s Lovers and Wives and Daughters, which was a few pages from completion when Gaskell died of a sudden heart attack in their second home in Hampshire, aged 55, in 1865.

Afterwards we stopped into the city’s Art Gallery and then headed to Mr Thomas’s Chop House for roast lamb and corned beef hash, then on to Sugar Junction to meet a blogger friend, the fabulous Lucy (aka Literary Relish), who I’d been corresponding with online for about two years but never met in real life. She graciously treated us to drinks and dessert at this cute café (one of the city’s many hip eateries) where she often hosts the Manchester Book Club, and we chatted about books and travel spots for a pleasant hour and a half.

On Monday we explored the Castlefield area with its canals and Roman ruins and went round both the Museum of Science and Industry and the People’s Museum, which together give a powerful sense of the city’s industrial and revolutionary past. We also toured the cathedral, took a peek at a Special Collections exhibit on the Gothic plus the main reading room at John Rylands Library, and browsed the huge selection at the main Waterstones branch. (On a future visit we are reliably informed that we must go find Sharston Books, a warehouse-scale secondhand shop out of town.) After a necessary pit stop for caffeine at The Foundation Coffee House and the best pizza we’ve ever had in the UK at Slice (including a Nutella and banana calzone for pudding), we headed over to the gig, which was terrific but not the purpose of this blog post.

Contrast between old and new Manchester: the hideous Beetham Tower on the left and Roman ruins in the foreground.

Our trip only spanned a Sunday and a bank holiday, so we missed seeing the inside of the hugely impressive Central Library and the 19th-century Portico Library. On Tuesday morning, though, we had just enough time before our train back to stop into Chetham’s Library. It’s a beautiful old library with rank after rank of leather-bound books sheltering amidst dark wood and mullioned windows. I love being in these kinds of places. They smell divine, and you can imagine holing up in a corner and reading all day, with the atmosphere beaming all kinds of lofty thoughts into your brain. We had the place to ourselves on this sunny morning and sat for a while in the bright alcove where Marx and Engels studied.

Apart from The Communist Manifesto, my reading on this trip was largely unrelated: My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff, a delightful literary memoir (review coming later this month); Number 11 by Jonathan Coe, a funny and mildly disturbing state-of-England and coming-of-age novel (releases November 11th); and The Mountain Can Wait by Sarah Leipciger, an atmospheric family novel set in the forests of Canada.

What have been some of your recent literary destinations? Do you like to read books related to the place you’re going, or do you choose your holiday reading at random?

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

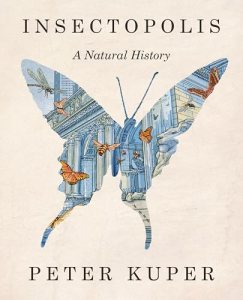

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,