10 Days in Spain (or at Sea) and What I Read

(Susan is the queen of the holiday travel and reading post – see her latest here.)

We spent the end of May in Northern Spain, with 20+-hour ferry rides across the English Channel either way. Thank you for your good thoughts – we were lucky to have completely flat crossings, and the acupressure bracelets that I wore seemed to do the job, such that not only did I not feel sick, but I even had an appetite for a meal in the ship’s café each day.

Not a bad day to be at sea. (All photos in this post are by Chris Foster.)

With no preconceived ideas of what the area would be like and zero time to plan, we went with the flow and decided on hikes each morning based on the weather. After a chilly, rainy start, we had warm but not uncomfortable temperatures by the end of the week. My mental picture of Spain was of hot beaches, but the Atlantic climate of the north is more like that of Britain’s. Green gorse-covered, livestock-grazed hills reminded us of parts of Wales. Where we stayed near Potes (reached by a narrow road through a gorge) was on the edge of Picos de Europa national park. The mountain villages and wildflower-rich meadows we passed on walks were reminiscent of places we’ve been in Italy or the Swiss and Austrian Alps.

The flora and fauna were an intriguing mix of the familiar (like blackbirds and blue tits) and the exotic (black kites, Egyptian vultures; some different butterflies; evidence of brown bears, wolves and wild boar, though no actual sightings, of course). One special thing we did was visit Wild Finca, a regenerative farming project by a young English couple; we’d learned about it from their short film shown at New Networks for Nature last year. We’d noted that the towns have a lot of derelicts and properties for sale, which is rather sad to see. They told us farm abandonment is common: those who inherit a family farm and livestock might just leave the animals on the hills and move to a city apartment to have modern conveniences.

I was especially taken by this graffiti-covered derelict restaurant and accommodation complex. As I explored it I was reminded of Cal Flyn’s Islands of Abandonment. It’s a wonder no one has tried to make this a roadside eatery again; it has a fantastic view!

It so happens that we were there for the traditional weekend when cattle are moved to new pastures. A cacophony of cowbells alerted us to herds going past our cottage window a couple of times, and once we were stopped on the road to let a small group through. We enjoyed trying local cheese and cider and had two restaurant meals, one at a trendy place in Potes and one at a roadside diner where we tried the regional speciality fabada, a creamy bean stew with sausage chunks.

Sampling local products and reading The Murderer’s Ape.

With our meager Spanish we just about got by. I used a phrase book so old it still referred to pesetas to figure out how to ask for roundtrip tickets, while my husband had learned a few useful restaurant-going phrases from the Duolingo language-learning app. For communicating with the cottage owner, though, we had to resort to Google Translate.

A highlight of our trip was the Fuente Dé cable car to 1900 meters / ~6200 feet above sea level, where we found snowbanks, Alpine choughs, and trumpet gentians. That was a popular spot, but on most of our other walks we didn’t see another human soul. We felt we’d found the real, hidden Spain, with a new and fascinating landscape around every corner. We didn’t make it to any prehistoric caves, alas – we would probably have had to book that well in advance – but otherwise experienced a lot of the highlights of the area.

On our way back to Santander for the ferry, we stopped in two famous towns: Comillas, known for its modernist architecture and a palace designed by Gaudí; and Santillana del Mar, which Jean-Paul Sartre once called the most beautiful town in Spain. We did not manage any city visits – Barcelona was too far and there was no train service; that will have to be for another trip. It was a very low-key, wildlife-filled and relaxing time, just what we needed before plunging back into work and DIY.

Santillana del Mar

What I Read

On the journey there and in the early part of the trip:

The Murderer’s Ape by Jakob Wegelius (translated from the Swedish by Peter Graves): Sally Jones is a ship’s engineer who journeys from Portugal to India to clear her captain’s name when he is accused of murder. She’s also a gorilla. Though she can’t speak, she understands human language and communicates via gestures and simple written words. This was the perfect rip-roaring adventure story to read at sea; the twisty plot and larger-than-life characters who aid or betray Sally Jones kept the nearly 600 pages turning quickly. I especially loved her time repairing accordions with an instrument maker. This is set in the 1920s or 30s, I suppose, with early airplanes and maharajahs, but still long-distance sea voyages. Published by Pushkin Children’s, it’s technically a teen novel and the middle book in a trilogy, but neither fact bothered me at all.

The Murderer’s Ape by Jakob Wegelius (translated from the Swedish by Peter Graves): Sally Jones is a ship’s engineer who journeys from Portugal to India to clear her captain’s name when he is accused of murder. She’s also a gorilla. Though she can’t speak, she understands human language and communicates via gestures and simple written words. This was the perfect rip-roaring adventure story to read at sea; the twisty plot and larger-than-life characters who aid or betray Sally Jones kept the nearly 600 pages turning quickly. I especially loved her time repairing accordions with an instrument maker. This is set in the 1920s or 30s, I suppose, with early airplanes and maharajahs, but still long-distance sea voyages. Published by Pushkin Children’s, it’s technically a teen novel and the middle book in a trilogy, but neither fact bothered me at all.

& to see me through the rest of the week:

The Feast by Margaret Kennedy: Originally published in 1950, this was reissued by Faber in 2021 with a foreword by Cathy Rentzenbrink – had she not made much of it, I’m not sure how well I would have recognized the allegorical framework of the Seven Deadly Sins. In August 1947, we learn, a Cornish hotel was buried under a fallen cliff, and with it seven people. Kennedy rewinds a month to let us watch the guests arriving, and to plumb their interactions and private thoughts. We have everyone from a Lady to a lady’s maid; I particularly liked the neglected Cove children. It took me until the very end to work out precisely who died and which sin each one represented. The characters and dialogue glisten. This is intelligent, literary yet light, and so makes great vacation/beach reading.

Book of Days by Phoebe Power: A set of autobiographical poems about walking the Camino pilgrimage route. Power writes about the rigours of the road – what she carried in her pack; finding places to stay and food to eat – but also gives tender pen portraits of her fellow walkers, who have come from many countries and for a variety of reasons: to escape an empty nest, to make amends, to remember a departed lover. Whether the pilgrim is religious or not, the Camino seems like a compulsion. Often the text feels more like narrative prose, though there are some sections laid out in stanzas or forming shapes on the page to remind you it is verse. I think what I mean to say is, it doesn’t feel that it was essential for this to be poetry. Short vignettes in a diary may have been more to my taste.

Book of Days by Phoebe Power: A set of autobiographical poems about walking the Camino pilgrimage route. Power writes about the rigours of the road – what she carried in her pack; finding places to stay and food to eat – but also gives tender pen portraits of her fellow walkers, who have come from many countries and for a variety of reasons: to escape an empty nest, to make amends, to remember a departed lover. Whether the pilgrim is religious or not, the Camino seems like a compulsion. Often the text feels more like narrative prose, though there are some sections laid out in stanzas or forming shapes on the page to remind you it is verse. I think what I mean to say is, it doesn’t feel that it was essential for this to be poetry. Short vignettes in a diary may have been more to my taste.

Two favourite passages:

into cobbled elegance; it’s opening time for shops

selling vegetables and pan and gratefully I present my

Spanish and warmth so far collected, and receive in return

smiles, interest, tomatoes, cheese.

We are resolute, though unknowing

if we will succeed at this.

We are still children here –

arriving, not yet grown

up.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

I’d also downloaded from Edelweiss the recent travel memoir The Way of the Wild Goose by Beebe Bahrami, in which she walks sections of the Camino in France and Spain and reflects on why the path keeps drawing her back. It’s been a probing, beautiful read so far – I think this is the mild, generically spiritual quest feel Jini Reddy was trying to achieve with Wanderland.

I’d also downloaded from Edelweiss the recent travel memoir The Way of the Wild Goose by Beebe Bahrami, in which she walks sections of the Camino in France and Spain and reflects on why the path keeps drawing her back. It’s been a probing, beautiful read so far – I think this is the mild, generically spiritual quest feel Jini Reddy was trying to achieve with Wanderland.

Plus, I read a few e-books for paid reviews and parts of other library books, including a trio of Spain-appropriate memoirs: As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee, Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell, and A Parrot in the Pepper Tree by Chris Stewart – more about this last one in my first 20 Books of Summer post, coming up on Sunday.

Our next holiday, to the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, is just two weeks away! It’ll be very different, but no doubt equally welcome and book-stuffed.

10 Favorite Nonfiction Novellas from My Shelves

What do I mean by a nonfiction novella? I’m not claiming a new genre like Truman Capote did for the nonfiction novel (so unless they’re talking about In Cold Blood or something very similar, yes, I can and do judge people who refer to a memoir as a “nonfiction novel”!); I’m referring literally to any works of nonfiction shorter than 200 pages. Many of my selections even come well under 100 pages.

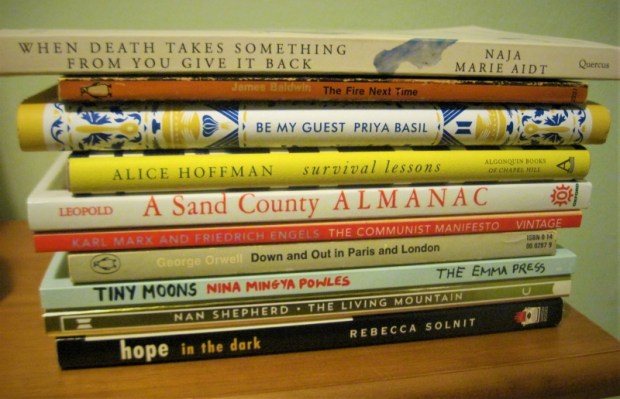

I’m kicking off this nonfiction-focused week of Novellas in November with a rundown of 10 of my favorite short nonfiction works. Maybe you’ll find inspiration by seeing the wide range of subjects covered here: bereavement, social and racial justice, hospitality, cancer, nature, politics, poverty, food and mountaineering. I’d reviewed all but one of them on the blog, half of them as part of Novellas in November in various years.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt [137 pages]: In March 2015 Aidt got word that her son Carl Emil was dead. The 25-year-old jumped out of his fifth-floor Copenhagen window after taking some mushrooms. The text is a collage of fragments: memories, dreams, dictionary definitions, journal entries, and quotations. The playful disregard for chronology and the variety of fonts, typefaces and sizes are a way of circumventing the feeling that grief has made words lose their meaning forever.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin [89 pages]: A hard-hitting book composed of two essays: “My Dungeon Shook,” is a letter addressed to his nephew and namesake on the 100th anniversary of emancipation; and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind,” which first appeared in the New Yorker and tells of a crisis of faith that hit Baldwin when he was a teenager and started to question to what extent Christianity of all stripes was upholding white privilege. This feels completely relevant, and eminently quotable, nearly 60 years later.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Be My Guest: Reflections on Food, Community and the Meaning of Generosity by Priya Basil [117 pages]: A thought-provoking essay that reaches into many different topics. Part of an Indian family that has lived in Kenya and England, Basil is used to culinary abundance. However, living in Berlin increased her awareness of the suffering of the Other – hundreds of thousands of refugees have entered the EU to be met with hostility. Yet the Sikh tradition she grew up in teaches kindness to strangers. She asks how we can all cultivate a spirit of generosity.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

Survival Lessons by Alice Hoffman [83 pages]: Hoffman wrote this 15 years after her own experience of breast cancer to encourage anyone going through a crisis. Each chapter title begins with the word “Choose” – a reminder that, even when you can’t choose your circumstances, you can choose your response. This has been beautifully put together with blue-tinted watercolor-effect photographs and an overall yellow and blue theme (along with deckle edge pages – a personal favorite book trait). It’s a sweet little memoir with a self-help note.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold [92 pages]: Few know how much of our current philosophy of wilderness and the human impact on the world is indebted to Aldo Leopold. This was published in 1949, but so much rings true today: how we only appreciate wildlife if we can put an economic value on it, the troubles we get into when we eradicate predators and let prey animals run rampant, and the danger of being disconnected from the land that supplies our very life. And all this he delivers in stunning, incisive prose.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels [70 pages]: Maybe you, like me, had always assumed this was an impenetrable tome of hundreds of pages? But, as I discovered when I read it on the train to Manchester some years ago, it’s very compact. That’s not to say it’s an easy read; I’ve never been politically or economically minded, so I struggled to follow the argument at times. Mostly what I appreciated was the language. Like The Origin of Species, it has many familiar lines and wonderful metaphors.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell [189 pages]: Orwell’s first book, published when he was 30, is an excellent first-hand account of the working and living conditions of the poor in two world cities. He works as a dishwasher and waiter in Paris hotel restaurants for up to 80 hours a week and has to pawn his clothes to scrape together enough money to ward off starvation. Even as he’s conveying the harsh reality of exhaustion and indignity, Orwell takes a Dickensian delight in people and their eccentricities.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai by Nina Mingya Powles [85 pages]: This lovely pamphlet of food-themed essays arose from a blog Powles kept while in Shanghai on a one-year scholarship to learn Mandarin. From one winter to another, she explores the city’s culinary offerings and muses on the ways in which food is bound up with her memories of people and places. This is about how food can help you be at home. I loved how she used the senses – not just taste, but also smell and sight – to recreate important places in her life.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd [108 pages]: This is something of a lost nature classic. Composed during the later years of World War II but only published in 1977, it’s Shepherd’s tribute to her beloved Cairngorms, a mountain region of Scotland. But it’s not a travel or nature book in the way you might usually think of those genres. It’s a subtle, meditative, even mystical look at the forces of nature, which are majestic but also menacing. Shepherd dwells on the senses, the mountain flora and fauna, and the special quality of time and existence (what we’d today call mindfulness) achieved in a place of natural splendor and solitude.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit [143 pages]: Solnit believes in the power of purposeful individuals working towards social justice, even in the face of dispiriting evidence (e.g. the largest protests the world had seen didn’t stop the Iraq War). Instead of perfectionism, she advises flexibility and resilience; things could be even worse had we not acted. Her strong and stirring writing is a reminder that, though injustice is always with us, so is everyday heroism.

Keep in touch via Twitter (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). We’ll add any of your review links in to our master posts. Feel free to use the terrific feature image Cathy made and don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov.

Any suitably short nonfiction on your shelves?

Snow, Dog, Foot by Claudio Morandini: A Peirene Press Novella

Who could resist the title of this Italian bestseller? A black comedy about a hermit in the Italian Alps, it starts off like Robert Seethaler’s A Whole Life and becomes increasingly reminiscent of Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead with its remote setting, hunting theme, and focus on an older character of dubious mental health.

Adelmo Farandola hasn’t washed in years. Why bother since he only sees fellow humans every six months when he descends to the valley to stock up on food and wine? When he arrives at the general store at the start of autumn, though, he gets a surprise. The shopkeeper laughs at him, saying he nearly cleared her out the week before. Yet he doesn’t remember having been there since April. Sure enough, when he gets back to the cabin he sees that his stable is full of supplies. He also finds an old dog that won’t go away and soon starts talking to him.

Estranged from his brother, who co-owns the property, and still haunted by the trauma of the war years, when he had to hide in a mine shaft, Adelmo is used to solitude and starvation rations. But now, with the dog around, there’s an extra mouth to feed. Normally Adelmo might shoot an occasional chamois for food, but a pesky mountain ranger keeps coming by and asking if Adelmo has a shotgun – and whether he has a license for it.

When winter sets in and heavy snowfall and then an avalanche trap Adelmo and the dog in the cabin, they are driven to the limits of their resilience and imagination. The long-awaited thaw reveals something disturbing: a blackened human foot poking out of a snowdrift. Each day Adelmo forgets about the corpse and the dog has to remind him that the foot has been visible for a week now, so they really should alert someone down in the village…

The hints of Adelmo’s dementia and mental illness accumulate gradually, making him a highly unreliable point-of-view character. This is a taut story that alternates between moments of humor and horror. I was so gripped I read it in one evening sitting, and would call it one of the top two Peirene books I’ve read (along with The Looking-Glass Sisters by Gøhril Gabrielsen).

My rating:

Snow, Dog, Foot will be published in the UK on the 15th. It was translated from the Italian by J. Ockenden, who won the 2019 Peirene Stevns Translation Prize for the work in progress. With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

Peirene Press issues its novellas in thematic trios. This is the first in 2020’s “Closed Universe” series, which will also include Ankomst by Gøhril Gabrielsen, about a Norwegian climatologist who has left her family to study seabird parenting and meet up with a lover; and The Pear Field by Nana Ekvtimishvili, set at a Georgian orphanage. (I’m especially keen on the former.)

Books of Summer #18–20: Alan Garner, Peter Matthiessen, Lorrie Moore

I’m sneaking in just in time here, on the very last day of the #20BooksofSummer challenge, with my final three reviews: two novellas, one of them a work of children’s fantasy; and a nature/travel classic that turns into something more like a spiritual memoir.

The Owl Service by Alan Garner (1967)

I’d heard of Garner, a British writer of classic children’s fantasy novels, but never read any of his work until I picked this up from the free bookshop where I volunteer on a Friday. My husband remembers reading Elidor (also a 1990s TV series) as a boy, but I’m not sure Garner was ever well known in America. Perhaps if I’d discovered this right after the Narnia series when I was a young child, I would have been captivated. I did enjoy the rural Welsh setting, and to start with I was intrigued by the setup: curious about knocking and scratching overhead, Alison and her stepbrother Roger find a complete dinner service up in the attic of this house Alison inherited from her late father. Alison becomes obsessed with tracing out the plates’ owl pattern – which disappears when anyone else, like Nancy the cook, looks at them.

I’d heard of Garner, a British writer of classic children’s fantasy novels, but never read any of his work until I picked this up from the free bookshop where I volunteer on a Friday. My husband remembers reading Elidor (also a 1990s TV series) as a boy, but I’m not sure Garner was ever well known in America. Perhaps if I’d discovered this right after the Narnia series when I was a young child, I would have been captivated. I did enjoy the rural Welsh setting, and to start with I was intrigued by the setup: curious about knocking and scratching overhead, Alison and her stepbrother Roger find a complete dinner service up in the attic of this house Alison inherited from her late father. Alison becomes obsessed with tracing out the plates’ owl pattern – which disappears when anyone else, like Nancy the cook, looks at them.

I gather that Garner frequently draws on ancient legend for his plots. Here he takes inspiration from Welsh myths, but the background was so complex and unfamiliar that I could barely follow along. This meant that the climactic ‘spooky’ scenes failed to move me. Instead, I mostly noted the period slang and the class difference between the English children and Gwyn, Nancy’s son, who’s forbidden from speaking Welsh (Nancy says, “I’ve not struggled all these years in Aber to have you talk like a labourer”) and secretly takes elocution lessons to sound less ‘common’.

Can someone recommend a Garner book I might get on with better?

My rating:

The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen (1978)

For two months of 1973, from late September to late November, Matthiessen joined zoologist George Schaller on a journey from the Nepalese Himalayas to the Tibetan Plateau to study Himalayan blue sheep. Both also harbored a hope of spotting the elusive snow leopard.

For two months of 1973, from late September to late November, Matthiessen joined zoologist George Schaller on a journey from the Nepalese Himalayas to the Tibetan Plateau to study Himalayan blue sheep. Both also harbored a hope of spotting the elusive snow leopard.

Matthiessen had recently lost his partner, Deborah Love, to cancer, and left their children behind – at residential schools or with family friends – to go on this spirit-healing quest. Though he occasionally feels guilty, especially about the eight-year-old, his thoughts are usually on the practicalities of the mountain trek. They have sherpas to carry their gear, and they stop in at monasteries but also meet ordinary people. More memorable than the human encounters, though, are those with the natural world. Matthiessen watches foxes hunting and griffons soaring overhead; he marvels at alpine birds and flora.

The writing is stunning. No wonder this won a 1979 National Book Award (in the short-lived “Contemporary Thought” category, which has since been replaced by a general nonfiction award). It’s a nature and travel writing classic. However, it took me nearly EIGHTEEN MONTHS to read, in all kinds of fits and starts (see below), because I could rarely read more than part of one daily entry at a time. I struggle with travel narratives in general – perhaps I think it’s unfair to read them faster than the author lived through them? – but there’s also an aphoristic density to the book that requires unhurried, meditative engagement.

The mountains in their monolithic permanence remind the author that he will die. The question of whether he will ever see a snow leopard comes to matter less and less as he uses his Buddhist training to remind himself of tenets of acceptance (“not fatalism but a deep trust in life”) and transience: “In worrying about the future, I despoil the present”; what is this “forever getting-ready-for-life instead of living it each day”? I’m fascinated by Buddhism, but anyone who ponders life’s deep questions should get something out of this.

My rating:

Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? by Lorrie Moore (1994)

Thanks to Cathy for reminding me about this one – I had intended to make it one of my novellas for November, but as I was scrambling around to find a last couple of short books to make up my 20 I thought, “Frog! hey, that fits”* and picked it up.

Oddly, given that Moore is so well known for short stories, I’ve only ever read two of her novels (the other was A Gate at the Stairs). Berie Carr lives just over the border from Quebec in Horsehearts, a fictional town in upstate New York. She and her best friend Sils are teenagers at the tail end of the Vietnam War, and work at Storyland amusement park on the weekends and during the summer. When Sils gets into trouble, Berie starts pocketing money from the cash register to help her out, but it will only be so long until she gets caught and the course of her life changes.

Oddly, given that Moore is so well known for short stories, I’ve only ever read two of her novels (the other was A Gate at the Stairs). Berie Carr lives just over the border from Quebec in Horsehearts, a fictional town in upstate New York. She and her best friend Sils are teenagers at the tail end of the Vietnam War, and work at Storyland amusement park on the weekends and during the summer. When Sils gets into trouble, Berie starts pocketing money from the cash register to help her out, but it will only be so long until she gets caught and the course of her life changes.

Berie is recounting these pivotal events from adulthood, when she’s traveling in Paris with her husband, Daniel. There are some troubling aspects to their relationship that don’t get fully explored, but that seems to be part of the point: we are always works in progress, and never as psychologically well as we try to appear. I most enjoyed the book’s tone of gentle nostalgia: “Despite all my curatorial impulses and training, my priestly harborings and professional, courtly suit of the past, I never knew what to do with all those years of one’s life: trot around in them forever like old boots – or sever them, let them fly free?”

Moore’s voice here reminds me of Amy Bloom’s and Elizabeth McCracken’s, though I’ve generally enjoyed those writers more.

*There are a few literal references to frogs (as well as the understood slang for French people). The title phrase comes from a drawing Sils makes about their mission to find and mend all the swamp frogs that boys shoot with BB guns. Berie also remarks on the sound of a frog chorus, and notes that two decades later frogs seem to be disappearing from the earth. In both these cases frogs are metaphors for a lost innocence. “She has eaten the frog” is also, in French, a slang term for taking from the cash box.

(I can’t resist mentioning Berie and Sils’ usual snack: raw, peeled potatoes cut into quarters and spread with margarine and salt!)

My rating:

A recap of my 20 Books of Summer:

- I enjoyed my animal theme, which was broad enough to encompass straightforward nature books but also a wide variety of memoirs and fiction. In most cases there was a literal connection between the animal in the title and the book’s subject.

- I read just nine of my original choices, plus two of the back-ups. The rest were a mixture of: books I brought back from America, review copies, books I’d started last year and set aside for ages, and ones I had lying around and had forgotten were relevant.

- I accidentally split the total evenly between fiction and nonfiction: 10 of each.

- I happened to read three novels by Canadian authors. The remainder were your usual British and American suspects.

- The clear stand-out of the 20 was Crow Planet by Lyanda Lynn Haupt, followed closely by The Snow Leopard (see above) and The Seafarers by Stephen Rutt – all nonfiction!

- In my second tier of favorites were three novels: Fifteen Dogs, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, and Crow Lake.

I also had three DNFs that I managed to replace in time.

Hollow Kingdom by Kira Jane Buxton [a review copy – and one of my Most Anticipated titles]

(I managed the first 36 pages.) Do you have a friend who’s intimidatingly sharp, whose every spoken or written line leaps from wordplay to a joke to an allusion to a pun? That’s how I felt about Hollow Kingdom. It’s so clever it’s exhausting.

I wanted to read this because I’d heard it’s narrated by a crow. S.T. (Shit Turd) is an American Crow who lives with an electrician, Big Jim, in Seattle, along with Dennis the dumb bloodhound. One day Jim’s eyeball pops out and he starts acting crazy and spending all his time in the basement. On reconnaissance flights through the neighborhood, S.T. realizes that all the humans (aka “MoFos” or “Hollows”) are similarly deranged. He runs into a gang of zombies when he goes to the Walgreens pharmacy to loot medications. Some are even starting to eat their pets. (Uh oh.)

I wanted to read this because I’d heard it’s narrated by a crow. S.T. (Shit Turd) is an American Crow who lives with an electrician, Big Jim, in Seattle, along with Dennis the dumb bloodhound. One day Jim’s eyeball pops out and he starts acting crazy and spending all his time in the basement. On reconnaissance flights through the neighborhood, S.T. realizes that all the humans (aka “MoFos” or “Hollows”) are similarly deranged. He runs into a gang of zombies when he goes to the Walgreens pharmacy to loot medications. Some are even starting to eat their pets. (Uh oh.)

We get brief introductions to other animal narrators, including Winnie the Poodle and Genghis Cat. An Internet-like “Aura” allows animals of various species to communicate with each other about the crisis. I struggle with dystopian and zombie stuff, but I think I could make an exception for this. Although I do think it’s overwritten (one adverb and four adjectives in one sentence: “We left slowly to the gentle song of lugubrious paw pads and the viscous beat of crestfallen wings”), I’ll try it again someday.

Gould’s Book of Fish: A Novel in Twelve Fish by Richard Flanagan: I read the first 164 pages last year before stalling; alas, I could make no more headway this summer. It’s an amusing historical pastiche in the voice of a notorious forger and counterfeiter who’s sentenced to 14 years in Van Diemen’s Land. I could bear only so much of this wordy brilliance, and no more.

Gould’s Book of Fish: A Novel in Twelve Fish by Richard Flanagan: I read the first 164 pages last year before stalling; alas, I could make no more headway this summer. It’s an amusing historical pastiche in the voice of a notorious forger and counterfeiter who’s sentenced to 14 years in Van Diemen’s Land. I could bear only so much of this wordy brilliance, and no more.

Tisala by Richard Seward Newton: I guess I read the blurb and thought this was unmissable, but I should have tried to read a sample or some more reviews of it. I got to page 6 and found it so undistinguished and overblown that I couldn’t imagine reading another 560+ pages about a whale.

Tisala by Richard Seward Newton: I guess I read the blurb and thought this was unmissable, but I should have tried to read a sample or some more reviews of it. I got to page 6 and found it so undistinguished and overblown that I couldn’t imagine reading another 560+ pages about a whale.

For next year, I’m toying with the idea of a food and drink theme. Once again, this would include fiction and nonfiction that is specifically about food but also slightly more cheaty selections that happen to have the word “eats” or “ate” or a potential foodstuff in the title, or have an author whose name brings food to mind. I perused my shelf and found exactly 20 suitable books, so that seems like a sign! (The eagle-eyed among you may note that two of these were on my piles of potential reads for this summer, and two others on last summer’s. When will they ever actually get read?!)

Alternatively, I could just let myself have completely free choice from my shelves. My only non-negotiable criterion is that all 20 books must be ones that I own, to force me to get through more from my shelves (even if that includes review copies).

I was utterly entranced by my first two Haruki Murakami novels,

I was utterly entranced by my first two Haruki Murakami novels,  As the narrator makes his way to The Rat’s mountain hideaway, an hour and a half from the nearest town, he’s moving further from rational explanations and deeper into solitude and communion with ghosts. There’s some trademark Murakami strangeness, but the book is too short to give free rein to the magic realist plot, and I felt like there were too many loose ends after his return from The Rat’s, especially around his girlfriend’s disappearance.

As the narrator makes his way to The Rat’s mountain hideaway, an hour and a half from the nearest town, he’s moving further from rational explanations and deeper into solitude and communion with ghosts. There’s some trademark Murakami strangeness, but the book is too short to give free rein to the magic realist plot, and I felt like there were too many loose ends after his return from The Rat’s, especially around his girlfriend’s disappearance.