Winter Reads: Claire Tomalin, Daniel Woodrell & Picture Books

Mid-February approaches and we’re wondering if the snowdrops and primroses emerging here in the South of England mean that it will be farewell to winter soon, or if the cold weather will return as rumoured. (Punxsutawney Phil didn’t see his shadow, but that early-spring prediction is only valid for the USA, right?) I didn’t manage to read many seasonal books this year, but I did pick up several short works with “Winter” in the title: a little-known biographical play from a respected author, a gritty Southern Gothic novella made famous through a Jennifer Lawrence film, and two picture books I picked up at the library last week.

The Winter Wife by Claire Tomalin (1991)

A search of the university library catalogue turned up this Tomalin title I’d never heard of. It turns out to be a very short play (two acts of seven scenes each, but only running to 44 pages in total) about a trip abroad Katherine Mansfield took with her housekeeper?/companion, Ida Baker, in 1920. Ida clucks over Katherine like a nurse or mother hen, but there also seems to be latent, unrequited love there (Mansfield was bisexual, as I knew from fellow New Zealander Sarah Laing’s fab graphic memoir Mansfield and Me). Katherine, for her part, alternately speaks to Ida, whom she nicknames “Jones,” with exasperation and fondness. The title comes from a moment late on when Katherine tells Ida “you’re the perfect friend – more than a friend. You know what you are, you’re what every woman needs: you’re my true wife.” Maybe what we’d call a “work wife” today, but Ida blushes with pride.

Tomalin had already written a full-length biography of Mansfield, but insists she barely referred to it when composing this. The backdrops are minimal: a French sleeper train; Isola Bella, a villa on the French Riviera; and Dr. Bouchage’s office. Mansfield was ill with tuberculosis, and the continental climate was a balm: “The sun gets right into my bones and makes me feel better. All that English damp was killing me. I can’t think why I ever tried to live in England.” There are also financial worries. The Murrys keep just one servant, Marie, a middle-aged French woman who accompanies her on this trip, but Katherine fears they’ll have to let her go if she doesn’t keep earning by her pen.

Through Katherine’s conversations with the doctor, we catch up on her romantic history – a brief first marriage, a miscarriage, and other lovers. Dr. Bouchage believes her infertility is a result of untreated gonorrhea. He echoes Ida in warning Katherine that she’s working too hard – mostly reviewing books for her husband John Middleton Murry’s magazine, but also writing her own short stories – when she should be resting. Katherine retorts, “It is simply none of your business, Jones. Dr Bouchage: if I do not work, I might as well be dead, it’s as simple as that.”

She would die not three years later, a fact that audiences learn through a final flash-forward where Ida, in a monologue, contrasts her own long life (she lived to 90 and Tomalin interviewed her when she was 88) with Katherine’s short one. “I never married. For me, no one ever equalled Katie. There was something golden about her.” Whereas Katherine had mused, “I thought there was going to be so much life then … that it would all be experience I could use. I thought I could live all sorts of different lives, and be unscathed…”

The play is, by its nature, slight, but gives a lovely sense of the subject and her key relationships – I do mean to read more by and about Mansfield. I wonder if it has been performed much since. And how about this for unexpected literary serendipity?

Yes, it’s that Rachel Joyce. (University library)

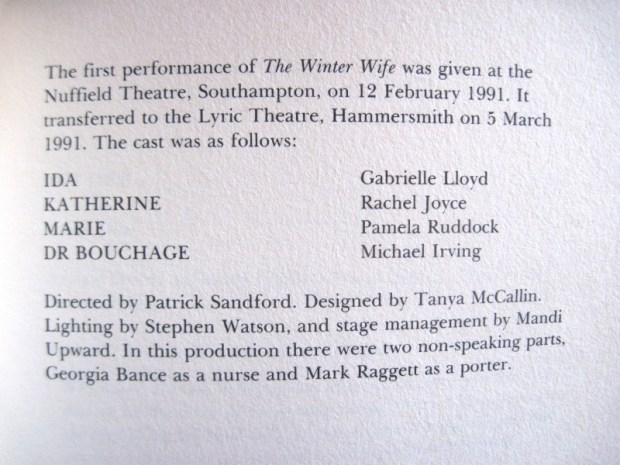

Winter’s Bone by Daniel Woodrell (2006)

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

I’d seen the movie but hadn’t remembered just how bleak and violent the story is, especially considering that the main character is a teenage girl. Ree Dolly lives in Ozarks poverty with a mentally ill, almost catatonic mother and two younger brothers whom she is effectively raising on her own. Their father, Jessup, is missing; rumour has it that he lies dead somewhere for snitching on his fellow drug producers. But unless Ree can prove he’s not coming back, the bail bondsman will repossess the house, leaving the family destitute.

Forced to undertake a frozen odyssey to find traces of Jessup, she’s unwelcome everywhere she goes, even among extended family. No one is above hitting a girl, it seems, and just for asking questions Ree gets beaten half to death. Her only comfort is in her best friend, Gail, who’s recently given birth and married the baby daddy. Gail and Ree have long “practiced” on each other romantically. Without labelling anything, Woodrell sensitively portrays the different value the two girls place on their attachment. His prose is sometimes gorgeous –

Pine trees with low limbs spread over fresh snow made a stronger vault for the spirit than pews and pulpits ever could.

– but can be overblown or off-puttingly folksy:

Ree felt bogged and forlorn, doomed to a spreading swamp of hateful obligations.

Merab followed the beam and led them on a slow wamble across a rankled field

This was my second from Woodrell, after the short stories of The Outlaw Album. I don’t think I’ll need to try any more by him, but this was a solid read. (Secondhand – New Chapter Books, Wigtown)

Children’s picture books:

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor and Alex Morss [illus. Cinyee Chiu] (2019): My second book by this group; I read Busy Spring: Nature Wakes Up a couple of years ago. Granny Sylvie reassures her grandson that everything hasn’t died in winter, but is sleeping or in hiding beneath the ice or behind the scenes. As before, the only niggle is that European and North American species are both mentioned and it’s not made clear that they live in different places. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

The Lightbringers: Winter by Karin Celestine (2020): An unusual artistic style here: every spread is a photograph of felted woodland creatures. The focus is on midwinter and the hope of the light coming back – depicted as poppy seed heads, lit from within and carried by mouse, hare, badger and more. “The light will always return because it is guarded by small beings and they are steadfast in their task.” The first of four seasonal stories. (Public library)

Any wintry reading (or weather) for you lately?

Two Recommended January Releases: Dominicana and Let Me Be Frank

Much as I’d like to review books in advance of their release dates, that doesn’t seem to be how things are going this year. I hope readers will find it useful to learn about recent releases they might have missed.

This month I’m featuring a fictionalized immigration story from the Dominican Republic and a collection of autobiographical comics by a New Zealander.

Dominicana by Angie Cruz

(Published by John Murray on the 23rd)

It’s easy to assume that all the immigration (or Holocaust, or WWI; whatever) stories have been told. This is proof that that is not true; it felt completely fresh to me. Ana Canción is 11 when Juan Ruiz first proposes to her in 1961 – the same year dictator Rafael Trujillo is assassinated, throwing their native Dominican Republic into chaos. The Ruiz brothers are admired for their entrepreneurial spirit; they jet back and forth to New York City to earn money they plan to invest in a restaurant back home. To Ana’s parents, pairing their daughter with a man with such good prospects makes financial sense, so though Ana doesn’t love him and knows nothing about sex, she finds herself married to Juan at age 15. With fake papers that claim she’s 19, she arrives in New York on the first day of 1965 to start a new life.

It is not the idyll she expected. Ana often feels confused and isolated in their tiny apartment, and the political unrest in NYC (e.g. the assassination of Malcolm X) and in DR mirrors the turbulence of her marriage. Juan is violent and unfaithful, and although Ana dreams of leaving him she soon learns that she is pregnant and has to think of her duty to her family, who expect to join her in America. The content of the novel could have felt like heavy going, but Ana is such a plucky and confiding narrator that you’re drawn into her world and cheer for her as she comes up with ways to earn money of her own (such as selling pastelitos to homesick factory workers and at the World’s Fair) and figures out what she wants from life.

It is not the idyll she expected. Ana often feels confused and isolated in their tiny apartment, and the political unrest in NYC (e.g. the assassination of Malcolm X) and in DR mirrors the turbulence of her marriage. Juan is violent and unfaithful, and although Ana dreams of leaving him she soon learns that she is pregnant and has to think of her duty to her family, who expect to join her in America. The content of the novel could have felt like heavy going, but Ana is such a plucky and confiding narrator that you’re drawn into her world and cheer for her as she comes up with ways to earn money of her own (such as selling pastelitos to homesick factory workers and at the World’s Fair) and figures out what she wants from life.

This allowed me to imagine what it would be like to have an arranged marriage and arrive in a country not knowing a word of the language. Cruz based the story on her mother’s experience, even though her mother thought her life was too common and boring to interest anyone. The literary style – short chapters with no speech marks – could be offputting for some but worked for me, and I loved the tongue-in-cheek references to I Love Lucy. Had I only managed to read this in December, it would have been on my Best of 2019 list – it was first published in September by Flatiron Books, USA.

Let Me Be Frank by Sarah Laing

(Published by Lightning Books on the 16th)

Laing is a novelist and comics artist from New Zealand known for her previous graphic memoir, Mansfield and Me, about her obsession with acclaimed NZ writer Katherine Mansfield. This collection brings together the autobiographical comics that originally appeared on Laing’s blog of the same title in 2010‒19. She started posting the comics when she was writer-in-residence at the Frank Sargeson Centre in Auckland. (I know the name Sargeson because he helped Janet Frame when she was early in her career.)

Laing is a novelist and comics artist from New Zealand known for her previous graphic memoir, Mansfield and Me, about her obsession with acclaimed NZ writer Katherine Mansfield. This collection brings together the autobiographical comics that originally appeared on Laing’s blog of the same title in 2010‒19. She started posting the comics when she was writer-in-residence at the Frank Sargeson Centre in Auckland. (I know the name Sargeson because he helped Janet Frame when she was early in her career.)

So what is the book about? All of life, really: growing up with type 1 diabetes, having boyfriends, being part of a family, the constant niggle of body issues, struggling as a writer, and trying to be a good mother. Other specific topics include her teenage obsession with music (especially Morrissey) and her run-ins with various animals (a surprising number of dead possums!). She ruminates about the times when she hasn’t done enough to help people who were in trouble. She also admits her confusion about fashion: she is always looking for, but never finding, ‘her look’. And is she modeling a proper female identity for her children? “I feel like I’m betraying feminism, buying my daughter a fairy princess dress,” she frets.

But even as she expresses these worries, she wonders how genuine she can be since they form the basis of her art. Is she just “publically performing my neuroses”? The work/life divide is especially tricksy when your life inspires your work.

I took half a month to read these comics on screen, usually just a few pages a day. It’s a tough book to assess as a whole because there is such a difference between the full-color segments and the sketch-like black-and-white ones. There is also a ‘warts-and-all’ approach here, with typos and cross-outs kept in. (Two that made me laugh were “aesophegus” [for oesophagus] and “Diana Anthill”!) Overall, though, I think this is a relatable and fun book that would suit fans of Alison Bechdel and Roz Chast but should also draw in readers new to the graphic novel format.

My thanks to Eye/Lightning Books for sending me an e-book to review.

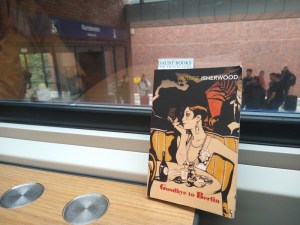

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

Isherwood intended for these six autofiction stories to contribute to a “huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin” titled The Lost. Two “Berlin Diary” segments from 1930 and 1933 bear witness to a change in tenor accompanying the rise of Nazism. Even in lighter pieces about a holiday at the Baltic coast and his friendship with a family who run a department store, menace creeps in through characters’ offhand remarks about “dirty Jews” ruining the country. The narrator, Christopher Isherwood, is a private English tutor staying in squalid boarding houses or spare rooms. His living conditions are mostly played for laughs – his landlady, Fraulein Schroeder, calls him “Herr Issyvoo” – but I was also reminded of George Orwell’s didactic realism. I had it in mind that Isherwood was homosexual; the only evidence of that here is his observation of the homoerotic tension between two young men, Otto and Peter, whom he meets on the Ruegen Island vacation, so he was still being coy in print. Famously, the longest story introduces Sally Bowles (played by Liza Minnelli in Cabaret), the lovable club singer who flits from man to man and feigns a carefree joy she doesn’t always feel. This is the second of two Berlin books; I will have to find the other and explore the rest of Isherwood’s work as I found this witty and humane, restrained but vigilant. (Little Free Library)

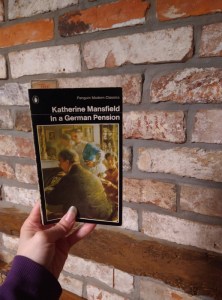

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

Mansfield was 19 when she composed this slim debut collection of arch sketches set in and around a Bavarian guesthouse. The narrator is a young Englishwoman traveling to take the waters for her health. A quiet but opinionated outsider (“I felt a little crushed … at the tone – placing me outside the pale – branding me as a foreigner”), she crafts pen portraits of a gluttonous baron, the fawning Herr Professor, and various meddling or air-headed fraus and frauleins. There are funny lines that rest on stereotypes (“you English … are always exposing your legs on cricket fields, and breeding dogs in your back gardens”; “a tired, pale youth … was recovering from a nervous breakdown due to much philosophy and little nourishment”) but also some alarming scenarios. One servant girl narrowly escapes being violated, while “The-Child-Who-Was-Tired” takes drastic action when another baby is added to her workload. Most of the stories are unmemorable, however. Mansfield renounced this early work as juvenile and inferior – her first publisher went bankrupt and when war broke out in Europe, sparking renewed interest in a book that pokes fun at Germans, she refused republishing rights. (Secondhand – Well-Read Books, Wigtown)

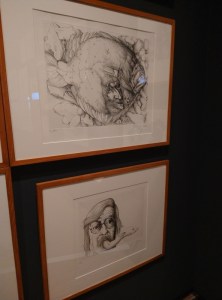

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

This posthumous prosimetric collection contains miniature essays, stories and poems, many of which seem autobiographical. By turns nostalgic and morbid, the pieces are very much concerned with senescence and last things. The black-and-white sketches, precise like Dürer’s but looser and more impressionistic, obsessively feature dead birds, fallen leaves, bent nails and shorn-off fingers. The speaker and his wife order wooden boxes in which their corpses will lie and store them in the cellar. One winter night they’re stolen, only to be returned the following summer. He has lost so many friends, so many teeth; there are few remaining pleasures of the flesh that can lift him out of his naturally melancholy state. Though, in Lübeck for the Christmas Fair, almonds might just help? The poetry happened to speak to me more than the prose in this volume. I’ll read longer works by Grass for future German Literature Months. My library has his first memoir, Peeling the Onion, as well as The Tin Drum, both doorstoppers. (Public library)

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

I must have first read this in my early twenties, and remembered it as spooky and atmospheric. I had completely forgotten that the action opens not at Manderley (despite the exceptionally famous first line, which forms part of a prologue-like first chapter depicting the place empty without its master and mistress to tend to it) but in Monte Carlo, where the unnamed narrator meets Maxim de Winter while she’s a lady’s companion to bossy Mrs. Van Hopper. This section functions to introduce Max and his tragic history via hearsay, but I found the first 60 pages so slow that I had trouble maintaining momentum thereafter, especially through the low-action and slightly repetitive scenes as the diffident second Mrs de Winter explores the house and tries to avoid Mrs Danvers, so I ended up skimming most of it.

I must have first read this in my early twenties, and remembered it as spooky and atmospheric. I had completely forgotten that the action opens not at Manderley (despite the exceptionally famous first line, which forms part of a prologue-like first chapter depicting the place empty without its master and mistress to tend to it) but in Monte Carlo, where the unnamed narrator meets Maxim de Winter while she’s a lady’s companion to bossy Mrs. Van Hopper. This section functions to introduce Max and his tragic history via hearsay, but I found the first 60 pages so slow that I had trouble maintaining momentum thereafter, especially through the low-action and slightly repetitive scenes as the diffident second Mrs de Winter explores the house and tries to avoid Mrs Danvers, so I ended up skimming most of it. I read my first work by Forster, My Life in Houses, last year, and adored it, so the fact that she was the author was all the more reason to read this when I found a copy in a library secondhand book sale. I started it immediately after our meeting about Rebecca, but I find biographies so dense and daunting that I’m still only a third of the way into it even though I’ve been liberally skimming.

I read my first work by Forster, My Life in Houses, last year, and adored it, so the fact that she was the author was all the more reason to read this when I found a copy in a library secondhand book sale. I started it immediately after our meeting about Rebecca, but I find biographies so dense and daunting that I’m still only a third of the way into it even though I’ve been liberally skimming.

It was my first time reading the famous “The Garden Party,” which likewise moves from a blithe holiday mood into something weightier. The Sheridans are making preparations for a lavish garden party dripping with flowers and food. Daughter Laura is dismayed when news comes that a man from the cottages has been thrown from his horse and killed, and thinks they should cancel the event. Everyone tells her not to be silly; of course it will go on as planned. The story ends when, after visiting his widow to hand over leftover party food, she unwittingly sees the man’s body and experiences an epiphany about the simultaneous beauty and terror of life. “Don’t cry,” her brother says. “Was it awful?” “No,” she replies. “It was simply marvellous.” Mansfield is especially good at first and last paragraphs. I’ll read more by her someday.

It was my first time reading the famous “The Garden Party,” which likewise moves from a blithe holiday mood into something weightier. The Sheridans are making preparations for a lavish garden party dripping with flowers and food. Daughter Laura is dismayed when news comes that a man from the cottages has been thrown from his horse and killed, and thinks they should cancel the event. Everyone tells her not to be silly; of course it will go on as planned. The story ends when, after visiting his widow to hand over leftover party food, she unwittingly sees the man’s body and experiences an epiphany about the simultaneous beauty and terror of life. “Don’t cry,” her brother says. “Was it awful?” “No,” she replies. “It was simply marvellous.” Mansfield is especially good at first and last paragraphs. I’ll read more by her someday. Now in its third year, the Best Small Fictions anthology collects the year’s best short stories under 1000 words. (I reviewed the two previous volumes for

Now in its third year, the Best Small Fictions anthology collects the year’s best short stories under 1000 words. (I reviewed the two previous volumes for

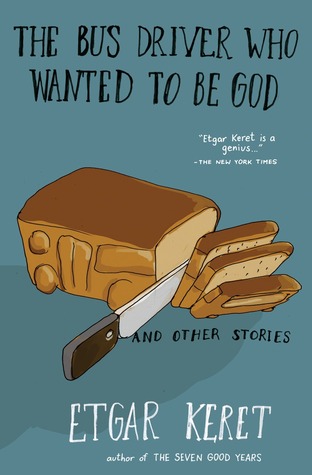

How can you not want to read a book with that title? Unfortunately, “The Story about a Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God” is the first story and probably the best, so it’s all a slight downhill journey from there. That story stars a bus driver who’s weighing justice versus mercy in his response to one lovelorn passenger, and retribution is a recurring element in the remainder of the book. Most stories are just three to five pages long. Important characters include an angel who can’t fly, visitors from the mouth of Hell in Uzbekistan, and an Israeli ex-military type with the ironic surname of Goodman who’s hired to assassinate a Texas minister for $30,000. You can never predict what decisions people will make, Keret seems to be emphasizing, or how they’ll choose to justify themselves; “Everything in life is just luck.”

How can you not want to read a book with that title? Unfortunately, “The Story about a Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God” is the first story and probably the best, so it’s all a slight downhill journey from there. That story stars a bus driver who’s weighing justice versus mercy in his response to one lovelorn passenger, and retribution is a recurring element in the remainder of the book. Most stories are just three to five pages long. Important characters include an angel who can’t fly, visitors from the mouth of Hell in Uzbekistan, and an Israeli ex-military type with the ironic surname of Goodman who’s hired to assassinate a Texas minister for $30,000. You can never predict what decisions people will make, Keret seems to be emphasizing, or how they’ll choose to justify themselves; “Everything in life is just luck.”

At any rate, I enjoyed Pearlman’s stories well enough. They all apparently take place in suburban Boston and many consider unlikely romances. My favorite was “Castle 4,” set in an old hospital. Zephyr, an anesthetist, falls in love with a cancer patient, while a Filipino widower who works as a security guard forms a tender relationship with the gift shop lady who sells his disabled daughter’s wood carvings. I also liked “Tenderfoot,” in which a pedicurist helps an art historian see that his heart is just as hard as his feet and that may be why he has an estranged wife. “Blessed Harry” amused me because the setup is a bogus e-mail requesting that a Latin teacher come speak at King’s College London (where I used to work). Two stories in a row (four in total, I’m told) center around Rennie’s antique shop – a little too Mitford quaint for me.

At any rate, I enjoyed Pearlman’s stories well enough. They all apparently take place in suburban Boston and many consider unlikely romances. My favorite was “Castle 4,” set in an old hospital. Zephyr, an anesthetist, falls in love with a cancer patient, while a Filipino widower who works as a security guard forms a tender relationship with the gift shop lady who sells his disabled daughter’s wood carvings. I also liked “Tenderfoot,” in which a pedicurist helps an art historian see that his heart is just as hard as his feet and that may be why he has an estranged wife. “Blessed Harry” amused me because the setup is a bogus e-mail requesting that a Latin teacher come speak at King’s College London (where I used to work). Two stories in a row (four in total, I’m told) center around Rennie’s antique shop – a little too Mitford quaint for me.