Reading Ireland Month, Part II: Hughes, Kennedy, Murray

My second contribution to Reading Ireland Month after a first batch that included poetry and a novel.

Today I have a poetry collection based around science and travel, and two multi-award-winning novels, one set in the thick of the Troubles in Belfast and another about the crumbling of an ordinary suburban family.

Gathering Evidence by Caoilinn Hughes (2014)

I bought this in the same order as Patricia Lockwood’s poetry collection, thinking a segue to another genre within an author’s oeuvre (I’d enjoyed Hughes’s 2018 debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp) might be a clever strategy. That worked out with Lockwood, but not as well here. A collection about scientific discoveries and medical advances seemed likely to be up my street. “The Moon Should Be Turned” is about the future of the HeLa cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks; poems are dedicated to the Curies and Johannes Kepler and one has Fermi as a main character. Russian nuclear force is a background menace. There are also some poems about growing up in Dublin and travels in the Andes. “Vagabond Monologue” stood out for its voice, “Marbles” for its description of childhood booty: “A netted bag of green glass marbles with aquamarine swirls / deep in the otherworld of spherical transparency (simultaneous opacity) / was the first thing I ever stole when I was three and far from the last.” Elsewhere, though, I found the precision vocabulary austere and offputting. (New purchase with Amazon voucher)

I bought this in the same order as Patricia Lockwood’s poetry collection, thinking a segue to another genre within an author’s oeuvre (I’d enjoyed Hughes’s 2018 debut novel, Orchid & the Wasp) might be a clever strategy. That worked out with Lockwood, but not as well here. A collection about scientific discoveries and medical advances seemed likely to be up my street. “The Moon Should Be Turned” is about the future of the HeLa cells harvested from Henrietta Lacks; poems are dedicated to the Curies and Johannes Kepler and one has Fermi as a main character. Russian nuclear force is a background menace. There are also some poems about growing up in Dublin and travels in the Andes. “Vagabond Monologue” stood out for its voice, “Marbles” for its description of childhood booty: “A netted bag of green glass marbles with aquamarine swirls / deep in the otherworld of spherical transparency (simultaneous opacity) / was the first thing I ever stole when I was three and far from the last.” Elsewhere, though, I found the precision vocabulary austere and offputting. (New purchase with Amazon voucher) ![]()

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (2022)

Despite its many accolades, not least a shortlisting for the Women’s Prize, I couldn’t summon much enthusiasm for reading a novel about the Troubles. I don’t know why I tend to avoid this topic; perhaps it’s the insidiousness of fighting that’s not part of a war somewhere else, but ongoing domestic terrorism instead. Combine that with an affair – Cushla is a 24-year-old schoolteacher who starts sleeping with a middle-aged, married barrister she meets in her family’s pub – and it sounded like a tired, ordinary plot. But after this won last year’s McKitterick Prize (for debut authors over 40) and I was sent the whole shortlist in thanks for being a manuscript judge, I thought I should get over myself and give it a try.

Little surprise that Kennedy’s writing – compassionate, direct, heart-rending – is what sets the book apart. With no speech marks, radio reports of everyday atrocities blend in with thoughts and conversations. We meet and develop fondness for characters across classes and the Catholic–Protestant divide: Cushla’s favourite pupil, Davy, whose father was assaulted in the street; her alcoholic mother, Gina, who knows more than she lets on, despite her inebriation; Gerry, a colleague who takes Cushla on friend dates and covers for her when she goes to see Michael. An Irish language learning circle introduces the 1970s bourgeoisie with their dinner parties and opinions.

Little surprise that Kennedy’s writing – compassionate, direct, heart-rending – is what sets the book apart. With no speech marks, radio reports of everyday atrocities blend in with thoughts and conversations. We meet and develop fondness for characters across classes and the Catholic–Protestant divide: Cushla’s favourite pupil, Davy, whose father was assaulted in the street; her alcoholic mother, Gina, who knows more than she lets on, despite her inebriation; Gerry, a colleague who takes Cushla on friend dates and covers for her when she goes to see Michael. An Irish language learning circle introduces the 1970s bourgeoisie with their dinner parties and opinions.

This doesn’t read like a first novel at all, with each character fully realized and the plot so carefully constructed that I was as shocked as Cushla by a revelation four-fifths of the way through. Desire is bound up with guilt; can anyone ever be happy when violence is so ubiquitous and random? “Booby trap. Incendiary device. Gelignite. Nitroglycerine. Petrol bomb. Rubber bullets. Saracen. Internment. The Special Powers Act. Vanguard. The vocabulary of a seven-year-old child now.” But a brief framing episode set in 2015 gives hope of life beyond seemingly inescapable tragedy. (Free from the Society of Authors) ![]()

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray (2023)

“The trouble is coming from inside; from his family. And unless something happens to stop it, it will keep billowing out, worse and worse”

Another great Irish novel I nearly missed out on, despite it being shortlisted for the Booker Prize and Writers’ Prize and winning the inaugural Nero Book Awards’ Gold Prize, this one because I was daunted by its doorstopper proportions. I’d gotten it in mind that it was all about money: Dickie Barnes’s car dealership is foundering and the straitened circumstances affect his whole family (wife Imelda, teenage daughter Cass, adolescent son PJ). A belated post-financial crash novel? Again, it sounded tired, maybe clichéd.

But actually, this turned out to be just the kind of wry, multi-perspective dysfunctional family novel that I love, such that I was mostly willing to excuse a baggy midsection. Murray opens with long sections of close third person focusing on each member of the Barnes family in turn. Cass is obsessed with sad-girl poetry and her best friend Elaine, but self-destructive habits threaten her university career before it’s begun. PJ is better at making friends through online gaming than in real life because of his family’s plunging reputation, so concocts a plan to run away to Dublin. Imelda is flirting with Big Mike, who’s taking over the dealership, but holds out hope that Dickie’s wealthy father will bail them out. Dickie, under the influence of a weird handyman named Victor, has become fixated on eradicating grey squirrels and building a bunker to keep his family safe.

But actually, this turned out to be just the kind of wry, multi-perspective dysfunctional family novel that I love, such that I was mostly willing to excuse a baggy midsection. Murray opens with long sections of close third person focusing on each member of the Barnes family in turn. Cass is obsessed with sad-girl poetry and her best friend Elaine, but self-destructive habits threaten her university career before it’s begun. PJ is better at making friends through online gaming than in real life because of his family’s plunging reputation, so concocts a plan to run away to Dublin. Imelda is flirting with Big Mike, who’s taking over the dealership, but holds out hope that Dickie’s wealthy father will bail them out. Dickie, under the influence of a weird handyman named Victor, has become fixated on eradicating grey squirrels and building a bunker to keep his family safe.

There are no speech marks throughout, and virtually no punctuation in Imelda’s sections. There are otherwise no clever tricks to distinguish the points-of-view, though. The voice is consistent. Murray doesn’t have to strain to sound like a teenage girl; he fully and convincingly inhabits each character (even some additional ones towards the end). I particularly liked the final “Age of Loneliness” section, which starts rotating between the perspectives more quickly, each one now in the second person. It all builds towards a truly thrilling yet inconclusive ending. I could imagine this as a TV miniseries for sure.

SPOILERS, if you’re worried about that sort of thing:

It was all the details I didn’t pick up from my pre-reading about The Bee Sting that made it so intricate and rewarding. Imelda’s awful upbringing in macho poverty and how it seemed that Rose, then Frank, might save her. The cruelty of Frank’s accidental death and the way that, for both Imelda and Dickie, being together seemed like the only way of getting over him, even if Imelda was marrying the ‘wrong’ brother. The recurrence of same-sex attraction for Dickie, then Cass. The irony of the bee sting that never was.

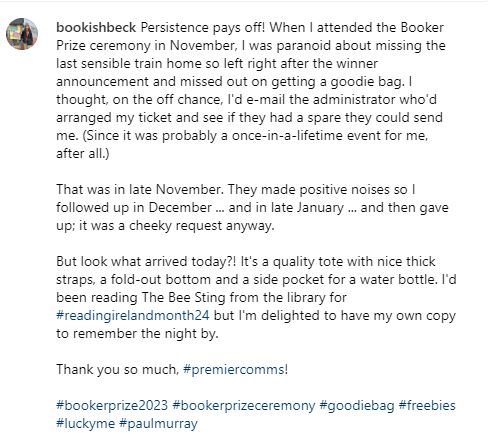

BUT. Yes, it’s too long, particularly Imelda’s central section. I had to start skimming to have any hope of making it through. Trim the whole thing by 200 pages and then we’re really talking. But I will certainly read Murray again, and most likely will revisit this book in the future to give it the attention it deserves. I read it from the library’s Bestsellers collection; the story of how I own a copy as of this week is a long one…

(Public library; free from the Booker Prize/Premier Comms) ![]()

I’ll be catching up on reviewing March releases in early April.

Happy Easter to those who celebrate!

Prize Updates: McKitterick Prize Winner and Wainwright Prize Longlists

It was my second year as a first-round manuscript judge for the McKitterick Prize; have a look at my rundown of the shortlist here.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

The winner, Louise Kennedy, and runner-up, Liz Hyder, were announced on 29 June. (Nominee Aamina Ahmad won a different SoA Award that night, the Gordon Bowker Volcano Prize for a novel focusing on the experience of travel away from home.) Other recipients included Travis Alabanza, Caroline Bird, Bonnie Garmus and Nicola Griffith. For more on all of this year’s SoA Award winners, see their website.

I’m a big fan of the Wainwright Prize for nature and conservation writing, and have been following it particularly closely since 2020, when I happened to read most of the nominees. In 2021 I also managed to read quite a lot from the longlists; 2022, the first year of an additional prize for children’s literature, saw me reading about a third of the total nominees.

This is the third year that I’ve been part of an “academy” of bloggers, booksellers, former judges and previously shortlisted authors asked to comment on a very long list of publisher submissions. I’m delighted that a few of my preferences made it through to the longlists.

My taste generally runs more to the narrative nature writing than the popular science or travel-based books. I find I’ve read just two from the Nature list (Bersweden and Huband) and one each from Conservation (Pavelle) and Children’s (Hargrave) so far.

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Nature Writing longlist:

- The Swimmer: The Wild Life of Roger Deakin, Patrick Barkham (Hamish Hamilton)

- The Flow: Rivers, Water and Wildness, Amy-Jane Beer (Bloomsbury)

- Where the Wildflowers Grow, Leif Bersweden (Hodder)

- Twelve Words for Moss, Elizabeth-Jane Burnett (Allen Lane)

- Cacophony of Bone, Kerri ní Dochartaigh (Canongate)

- Sea Bean, Sally Huband (Hutchinson)

- Ten Birds that Changed the World, Stephen Moss (Faber)

- A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast, Dorthe Nors, translated by Caroline Waight (Pushkin)

- The Golden Mole: And Other Living Treasure, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Talya Baldwin (Faber)

- Belonging: Natural Histories of Place, Identity and Home, Amanda Thomson (Canongate)

- Why Women Grow: Stories of Soil, Sisterhood and Survival, Alice Vincent (Canongate)

- Landlines, Raynor Winn (Penguin)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Writing on Conservation longlist:

- Sarn Helen: A Journey Through Wales, Past, Present and Future, Tom Bullough, illustrated by Jackie Morris (Granta)

- Beastly: A New History of Animals and Us, Keggie Carew (Canongate)

- Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans, Charles Clover (Ebury)

- Birdgirl, Mya-Rose Craig (Jonathan Cape)

- The Orchid Outlaw, Ben Jacob (John Murray)

- Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time, Kapka Kassabova (Jonathan Cape)

- Rooted: How Regenerative Farming Can Change the World, Sarah Langford (Viking)

- Black Ops and Beaver Bombing: Adventures with Britain’s Wild Mammals, Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall (Oneworld)

- Forget Me Not, Sophie Pavelle (Bloomsbury)

- Fen, Bog, and Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and its Role in the Climate Crisis, Annie Proulx (Fourth Estate)

- The Lost Rainforests of Britain, Guy Shrubsole (HarperCollins)

- Nomad Century: How to Survive the Climate Upheaval, Gaia Vince (Allen Lane)

The 2023 James Cropper Wainwright Prize for Children’s Writing on Nature and Conservation longlist:

- The Earth Book, Hannah Alice (Nosy Crow)

- The Light in Everything, Katya Balen, illustrated by Sydney Smith (Bloomsbury)

- Billy Conker’s Nature-Spotting Adventure, Conor Busuttil (O’Brien)

- Protecting the Planet: The Season of Giraffes, Nicola Davies, illustrated by Emily Sutton (Walker)

- Blobfish, Olaf Falafel (Walker)

- A Friend to Nature, Laura Knowles, illustrated by Rebecca Gibbon (Welbeck)

- Spark, M G Leonard (Walker)

- A Wild Child’s Book of Birds, Dara McAnulty (Macmillan)

- Leila and the Blue Fox, Kiran Millwood Hargrave, illustrated by Tom de Freston (Hachette Children’s Group)

- The Zebra’s Great Escape, Katherine Rundell, illustrated by Sara Ogilvie (Bloomsbury)

- Archie’s Apple, Hannah Shuckburgh, illustrated by Octavia Mackenzie (Little Toller)

- Grandpa and the Kingfisher, Anna Wilson, illustrated by Sarah Massini (Nosy Crow)

It’s impressive that women writers are represented so well this year: 9/12 for Nature, 8/12 for Conservation, and 8/12 for Children’s. Amusingly, Katherine Rundell is on TWO of the lists. There are also, refreshingly, several BIPOC authors, and – I think for the first time ever – a work in translation (A Line in the World by Dorthe Nors, which I have as a set-aside proof copy and will get back into at once).

Here is where I have to admit that quite a number of the nominees, overall, are books I DNFed, authors whose work I’ve tried before and not enjoyed, or books I’ve been turned off of by the reviews. I’ll not mention these by name just now, and will leave any predictions for a future date when I’ve read a few more of the nominees. It seems that I’m most likely to catch up with the majority of the children’s longlist, if anything.

The shortlists will be announced on 10 August, and winners will be announced on 14 September at a 10th Anniversary live event held as part of the Kendal Mountain Festival in Cumbria (tickets available here).

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see shortlisted?

Introducing the 2023 McKitterick Prize Shortlist

For the second year in a row, I was a first-round judge for the McKitterick Prize (for a first novel by a writer over 40), helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts. Perhaps lockdowns gave people time to achieve a long-held goal of writing a novel, because submissions were up by 50%. None of the manuscripts made it through to the shortlist this year or last, but one day it could happen!

The Society of Authors kindly sent me a parcel with five of the shortlisted novels, and I picked up the remaining one from the library this week. Below are synopses from Goodreads and author bios from the SoA:

The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad (Sceptre): “Sent back to his birthplace—Lahore’s notorious red-light district—to hush up the murder of a girl, a man finds himself in an unexpected reckoning with his past. … Profoundly intimate and propulsive, The Return of Faraz Ali is a spellbindingly assured first novel that poses a timeless question: Whom do we choose to protect, and at what price?”

The Return of Faraz Ali by Aamina Ahmad (Sceptre): “Sent back to his birthplace—Lahore’s notorious red-light district—to hush up the murder of a girl, a man finds himself in an unexpected reckoning with his past. … Profoundly intimate and propulsive, The Return of Faraz Ali is a spellbindingly assured first novel that poses a timeless question: Whom do we choose to protect, and at what price?”

Aamina Ahmad was born and raised in London, where she worked for BBC Drama and other independent television companies as a script editor. Her play The Dishonoured was produced by Kali Theatre Company in 2016. She has an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and is a recipient of a Stegner Fellowship from Stanford University, a Pushcart Prize and a Rona Jaffe Writers Award. Her short fiction has appeared in journals including One Story, the Southern Review and Ecotone. She teaches creative writing at the University of Minnesota.

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo (Hamish Hamilton): “Yejide and Darwin will meet inside the gates of Fidelis, Port Angeles’s largest and oldest cemetery, where the dead lie uneasy in their graves and a reckoning with fate beckons them both. A masterwork of lush imagination and immersive lyricism, When We Were Birds is a spellbinding novel about inheritance, loss, and love’s seismic power to heal.”

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo (Hamish Hamilton): “Yejide and Darwin will meet inside the gates of Fidelis, Port Angeles’s largest and oldest cemetery, where the dead lie uneasy in their graves and a reckoning with fate beckons them both. A masterwork of lush imagination and immersive lyricism, When We Were Birds is a spellbinding novel about inheritance, loss, and love’s seismic power to heal.”

Ayanna Lloyd Banwo is a writer from Trinidad and Tobago. She is a graduate of the University of the West Indies and holds an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia, where she is now a Creative and Critical Writing PhD candidate. Her work has been published in Moko Magazine, Small Axe and PREE, among others, and shortlisted for the Small Axe Literary Competition and the Wasafiri New Writing Prize. When We Were Birds, Ayanna’s first novel, was shortlisted for the Jhalak Prize and won the OCM Bocas Prize for Fiction. She is now working on her second novel. Ayanna lives with her husband in London.

The Gifts by Liz Hyder (Manilla Press): “October 1840. A young woman staggers alone through a forest in the English countryside as a huge pair of impossible wings rip themselves from her shoulders. In London, rumours of a “fallen angel” cause a frenzy across the city, and a surgeon desperate for fame and fortune finds himself in the grips of a dangerous obsession. … [A] spellbinding tale told through five different perspectives …, it explores science, nature and religion, enlightenment, the role of women in society and the dark danger of ambition.”

The Gifts by Liz Hyder (Manilla Press): “October 1840. A young woman staggers alone through a forest in the English countryside as a huge pair of impossible wings rip themselves from her shoulders. In London, rumours of a “fallen angel” cause a frenzy across the city, and a surgeon desperate for fame and fortune finds himself in the grips of a dangerous obsession. … [A] spellbinding tale told through five different perspectives …, it explores science, nature and religion, enlightenment, the role of women in society and the dark danger of ambition.”

Liz Hyder has been making up stories for as long she can remember. She has a BA in drama from the University of Bristol and, in early 2018, won the Bridge Award/Moniack Mhor Emerging Writer Award. Bearmouth, her debut young adult novel, won a Waterstones Children’s Book Prize, the Branford Boase Award and was chosen as the Children’s Book of the Year by The Times. Originally from London, she now lives in South Shropshire. The Gifts is her debut adult novel.

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing): “Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, a shattering novel about a young woman caught between allegiance to community and a dangerous passion. … As tender as it is unflinching, Trespasses is a heart-pounding, heart-rending drama of thwarted love and irreconcilable loyalties, in a place what you come from seems to count more than what you do, or whom you cherish.”

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury Publishing): “Set in Northern Ireland during the Troubles, a shattering novel about a young woman caught between allegiance to community and a dangerous passion. … As tender as it is unflinching, Trespasses is a heart-pounding, heart-rending drama of thwarted love and irreconcilable loyalties, in a place what you come from seems to count more than what you do, or whom you cherish.”

Louise Kennedy grew up a few miles from Belfast. She is the author of the Women’s Prize-shortlisted novel Trespasses, and the acclaimed short story collection The End of the World is a Cul de Sac, and is the only woman to have been shortlisted twice for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award (2019 and 2020). Before starting her writing career, she spent nearly thirty years working as a chef. She lives in Sligo.

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn (Fig Tree): “One blustery night in 1928, a whale washes up on the shores of the English Channel. By law, it belongs to the King, but twelve-year-old orphan Cristabel Seagrave has other plans. She and the rest of the household … build a theatre from the beast’s skeletal rib cage. … As Cristabel grows into a headstrong young woman, World War II rears its head.”

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn (Fig Tree): “One blustery night in 1928, a whale washes up on the shores of the English Channel. By law, it belongs to the King, but twelve-year-old orphan Cristabel Seagrave has other plans. She and the rest of the household … build a theatre from the beast’s skeletal rib cage. … As Cristabel grows into a headstrong young woman, World War II rears its head.”

Joanna Quinn was born in London and grew up in the southwest of England, where her bestselling debut novel, The Whalebone Theatre, is set. Joanna has worked in journalism and the charity sector. She is also a short story writer, published by The White Review and Comma Press, among others. She lives in a village near the sea in Dorset.

Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Harvill Secker): “A seductive coming-of-age story about queer desire, Other Names for Love is a charged, hypnotic debut novel about a boy’s life-changing summer in rural Pakistan: a story of fathers, sons, and the consequences of desire. … Decades later, Fahad is living abroad when he receives a call from his mother summoning him home. … [A] tale of masculinity, inheritance, and desire set against the backdrop of a country’s violent history, told with uncommon urgency and beauty.”

Other Names for Love by Taymour Soomro (Harvill Secker): “A seductive coming-of-age story about queer desire, Other Names for Love is a charged, hypnotic debut novel about a boy’s life-changing summer in rural Pakistan: a story of fathers, sons, and the consequences of desire. … Decades later, Fahad is living abroad when he receives a call from his mother summoning him home. … [A] tale of masculinity, inheritance, and desire set against the backdrop of a country’s violent history, told with uncommon urgency and beauty.”

Taymour Soomro is the author of Other Names for Love and co-editor of Letters to a Writer of Colour. His writing has been published in the New Yorker, the New York Times and elsewhere. He is the recipient of fellowships from the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and the Sozopol Fiction Seminars. He has degrees from Cambridge University and Stanford Law School and a PhD in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. He currently teaches on the MFA program at Bennington College.

Fellow judge Selma Dabbagh summarises the shortlist thus: “Family estates in rural Pakistan (Other Names for Love) and England (The Whalebone Theatre) fall into decline reflecting the hubris and short-sightedness of their owners[;] in The Return of Faraz Ali, it is the decaying grandeur of the courtesans of Lahore that is lovingly depicted. Whereas in both The Gifts and When We Were Birds, the otherworldly brings new possibilities to the tawdry and impoverished as mystical wings fly over the slums of Victorian London and the graveyards of Trinidad.”

I was already interested in reading a couple of these novels, and was pleased to discover a few new-to-me titles. As it’s also shortlisted for the Women’s Prize (which will be awarded on Wednesday), it seems to make sense to start with Trespasses, and I’m also particularly keen on The Gifts, which sounds like a great holiday read and right up my street, so I’m packing it for our trip to Scotland later this month. One or more of the others might end up on my 20 Books of Summer list. I’ll be sure to follow up with reviews of any I manage to read this summer.

The winner and runner-up will be announced at the SoA Awards ceremony in London on 29 June. I’ll be away at the time but will hope to watch part of the livestream. For more on all of the SoA Awards, see the press release on their website.

See any nominees you’ve read? Who would you like to see win?

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition.

Etymology and Shakespeare studies are the keys to solving a cold case in Susie Dent’s clever, engrossing mystery, Guilty by Definition. Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down.

Psychoanalysis, motherhood, and violence against women are resounding themes in Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding. As history repeats itself one sweltering Paris summer, the personal and political structures undergirding the protagonists’ parallel lives come into question. This fearless, sophisticated work ponders what to salvage from the past—and what to tear down. Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

Clinical Intimacy’s mysterious antihero comes to life through interviews with his family, friends and clients. The brilliant oral history format builds a picture of isolation among vulnerable populations, only alleviated by care and touch—especially during Covid-19. Ewan Gass’s intricate story reminds us of the ultimate unknowability of other people.

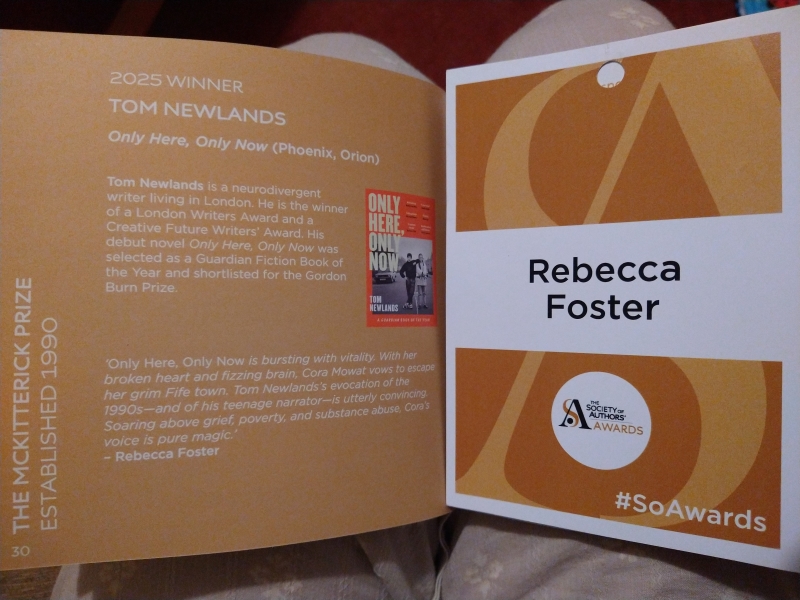

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Only Here, Only Now is bursting with vitality. With her broken heart and fizzing brain, Cora Mowat vows to escape her grim Fife town. Tom Newlands’s evocation of the 1990s—and of his teenage narrator—is utterly convincing. Soaring above grief, poverty, and substance abuse, Cora’s voice is pure magic.

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted]

Hyper by Agri Ismaïl [I longlisted it – and then shortlisted it – but was outvoted] How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

How to Be Somebody Else by Miranda Pountney [It had two votes to make the shortlist, but because it was so similar to Scaffolding in its basics (a thirtysomething woman in a big city, the question of motherhood, and pregnancy loss) we decided to cut it.]

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in

When Doll English is kidnapped by the Ferdia brothers in revenge for a huge loss on a drug deal, his girlfriend, mother and brother must go to unexpected lengths to set him free. There’s plenty of cursing and violence in this small-town crime caper, yet Barrett has a light touch; the dialogue, especially, is funny. The dialect is easy enough to decipher. Nicky, Doll’s girlfriend, lost both parents young and works in a hotel bar. She’s a strong character reminiscent of the protagonist in  Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters.

Inspired by a real-life disaster involving a train on the approach to Paris’s Montparnasse station in 1895. The Author’s Note at the end reveals the blend of characters included: people known to have been on that particular train, whether as crew or passengers; those who might have journeyed on it because they spent time in Paris at around that period (such as Irish playwright John Millington Synge); and those made up from scratch. It’s a who’s-who of historical figures, many of whom represent different movements or social issues, such as a woman medical student and an African American painter who can pass as white in certain circumstances. Donoghue clearly intends to encompass the entire social hierarchy, from a maid to a politician with a private carriage. She also crafts a couple of queer encounters. This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle.

This was a reread for book club, and oh how brilliant it is. I’m more convinced than ever that the memoir-in-essays is a highly effective form because it focuses on themes or moments of great intensity and doesn’t worry about accounting for all the boring intermediate material. A few of these pieces feel throwaway, but together they form a vibrant picture of a life and also inspire awe at what the human body can withstand. No doubt on Wednesday we will each pick out different essays that resonated the most with us, perhaps because they run very close to our own experience. I imagine our discussion will start there – and with sharing our own NDEs. Stylistically, the book has a lot in common with O’Farrell’s fiction, which often employs the present tense and a complicated chronology. The present tense and a smattering of second person make the work immediate and invite readers to feel their way into her situations. Otherwise, my thoughts are as before – the last two essays are the pinnacle. This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

This is actually her third children’s book, after Where Snow Angels Go (2020) and The Boy Who Lost His Spark (2022). All are illustrated by Daniela Jaglenka Terrazzini, who has a richly colourful and slightly old-fashioned style; she makes kids look as dignified as adults. The books are intended for slightly older children in that they’re on the longer side, have more words than pictures, and are more serious than average. They all weave in gentle magic as a way of understanding and coping with illness, a mental health challenge, or a disability.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

Information about coral reefs dying in Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar and Mothership by Greg Wrenn.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

An Uncle Frank in an Irish novel with no speech marks: Trespasses by Louise Kennedy and The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Quotes from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed in Intervals by Marianne Brooker and A Flat Place by Noreen Masud.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

Indigenous author, Native versus Catholic religion, and descriptions of abuse and cultural suppression at residential schools in Becoming Little Shell by Chris La Tray and A Council of Dolls by Mona Susan Power.

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

The protagonist is ‘Amy’, who lives in a tornado-ridden Oklahoma and whose sister, ‘Zoe’ – a handy A to Z of growing up there – has a mysterious series of illnesses that land her in hospital. The third person limited perspective reveals Amy to be a protective big sister who shoulders responsibility: “There is nothing in the world worse than Zoe having her blood drawn. Amy tries to show her the pictures [she’s taken of Zoe’s dog] at just the right moment, just right before the nurse puts the needle in”.

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,

In 2017 I reviewed Grudova’s surreal story collection,

Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”

Lucrezia di Cosimo de’ Medici is a historical figure who died at age 16, having been married off from her father’s Tuscan palazzo as a teenager to Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She was reported to have died of a “putrid fever” but the suspicion has persisted that her husband actually murdered her, a story perhaps best known via Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess.”