May Releases, Part II (Fiction): Le Blevennec, Lynch, Puchner, Stanley, Ullmann, and Wald

A cornucopia of May novels, ranging from novella to doorstopper and from Montana to Tunisia; less of a spread in time: only the 1980s to now. Just a paragraph on each to keep things simple. I’ll catch up soon with May nonfiction and poetry releases I read.

Friends and Lovers by Nolwenn Le Blevennec (2023; 2025)

[Translated from French by Madeleine Rogers]

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

Armelle, Rim, and Anna are best friends – the first two since childhood. They formed a trio a decade or so ago when they worked on the same magazine. Now in their mid-thirties, partnered and with children, they’re all gripped by a sexual “great awakening” and long to escape Paris and their domestic commitments – “we went through it, this mutiny, like three sisters,” poised to blow up the “perfectly executed choreography of work, relationships, children”. The friends travel to Tunisia together in December 2014, then several years later take a completely different holiday: a disaster-prone stay in a lighthouse-keeper’s cottage on an island off the coast of Brittany. They used to tolerate each other’s foibles and infidelities, but now resentment has sprouted up, especially as Armelle (the narrator) is writing a screenplay about female friendship that’s clearly inspired by Rim and Anna. Armelle is relatably neurotic (a hilarious French blurb for the author’s previous novel is not wrong: “Woody Allen meets Annie Ernaux”) and this is wise about intimacy and duplicity, yet I never felt invested in any of the three women or sufficiently knowledgeable about their lives.

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

A Family Matter by Claire Lynch

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

“The fluke of being born at a slightly different time, or in a slightly different place, all that might gift you or cost you.” At events for Small, Lynch’s terrific memoir about how she and her wife had children, women would speak up about how different their experience had been. Lesbians born just 10 or 20 years earlier didn’t have the same options. Often, they were in heterosexual marriages because that’s all they knew to do; certainly the only way they thought they could become mothers. In her research into divorce cases in the UK in the 1980s, Lynch learned that 90% of lesbian mothers lost custody of their children. Her aim with this earnest, delicate debut novel, which bounces between 2022 and 1982, is to imagine such a situation through close portraits of Heron, an ageing man with terminal cancer; his daughter, Maggie, who in her early forties bears responsibility for him and her own children; and Dawn, who loved Maggie desperately but felt when she met Hazel that she was “alive at last, at twenty-three.” How heartbreaking that Maggie knew only that her mother abandoned her when she was little; not until she comes across legal documents and newspaper clippings does she understand the circumstances. Lynch made the wise decision to invite sympathy for Heron from the start, so he doesn’t become the easy villain of the piece. Her compassion, and thus ours, is equal for all three characters. This confident, tender story of changing mores and steadfast love is the new Carol for our times. (Such a lovely but low-key novel was liable to make few ripples, so I’m delighted for Lynch that the U.S. release got a Read with Jenna endorsement.)

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Dream State by Eric Puchner

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

If it starts and ends with a wedding, it must be a comedy. If much of the in between is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, failure, and loss, it must be a tragedy. If it stretches towards 2050 and imagines a Western USA smothered in smoke from near-constant forest fires, it must be an environmental dystopian. Somehow, this novel is all three. The first 163 pages are pure delight: a glistening romantic comedy about the chaos surrounding Charlie and Cece’s wedding at his family’s Montana lake house in the summer of 2004. First half the wedding party falls ill with norovirus, then Charlie’s best friend, Garrett (who’s also the officiant), falls in love with the bride. Do I sound shallow if I admit this was the section I enjoyed the most? The rest of this Oprah’s Book Club doorstopper examines the fallout of this uneasy love triangle. Charlie is an anaesthesiologist, Cece a bookstore owner, and Garrett a wolverine researcher in Glacier National Park, which is steadily losing its wolverines and its glaciers. The next generation comes of age in a diminished world, turning to acting or addiction. There are still plenty of lighter moments: funny set-pieces, warm family interactions, private jokes and quirky descriptions. But this feels like an appropriately grown-up vision of idealism ceding to a reality we all must face. I struggled with a lack of engagement with the children, but loved Puchner’s writing so much on the sentence level that I will certainly seek out more of his work. Imagine this as a cross between Jonathan Franzen and Maggie Shipstead.

With thanks to Sceptre (Hodder) for the proof copy for review.

Consider Yourself Kissed by Jessica Stanley

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

Coralie is nearing 30 when her ad agency job transfers her from Australia to London in 2013. Within a few pages, she meets Adam when she rescues his four-year-old, Zora, from a lake. That Adam and Coralie will be together is never really in question. But over the next decade of personal and political events, we wonder whether they have staying power – and whether Coralie, a would-be writer, will lose herself in soul-destroying work and motherhood. Adam’s job as a political journalist and biographer means close coverage of each UK election and referendum. As I’ve thought about some recent Jonathan Coe novels: These events were so depressing to live through, who would want to relive them through fiction? I also found this overlong and drowning in exclamation points. Still, it’s so likable, what with Coralie’s love of literature (the title is from The Group) and adjustment to expat life without her mother; and secondary characters such as Coralie’s brother Daniel and his husband, Adam’s prickly mother and her wife, and the mums Coralie meets through NCT classes. Best of all, though, is her relationship with Zora. This falls solidly between literary fiction and popular/women’s fiction. Given that I was expecting a lighter romance-led read, it surprised me with its depth. It may well be for you if you’re a fan of Meg Mason and David Nicholls.

With thanks to Hutchinson Heinemann for the proof copy for review.

Girl, 1983 by Linn Ullmann (2021; 2025)

[Translated from Norwegian by Martin Aitken]

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

Ullmann is the daughter of actress Liv Ullmann and film director Ingmar Bergman. That pedigree perhaps accounts for why she got the opportunity to travel to Paris in the winter of 1983 to model for a renowned photographer. She was 16 at the time and spent the whole trip disoriented: cold, hungry, lost. Unable to retrace the way to her hotel and wearing a blue coat and red hat, she went to the only address she knew – that of the photographer, K, who was in his mid-forties. Their sexual relationship is short-lived and unsurprising, at least in these days of #MeToo revelations. Its specifics would barely fill a page, yet the novel loops around and through the affair for more than 250. Ullmann mostly pulls this off thanks to the language of retrospection. She splits herself both psychically and chronologically. There’s a “you” she keeps addressing, a childhood imaginary friend who morphs into a critical voice of conscience and then the self dissociated from trauma. And there’s the 55-year-old writer looking back with empathy yet still suffering the effects. The repetition made this something of a sombre slog, though. It slots into a feminist autofiction tradition but is not among my favourite examples.

With thanks to Hamish Hamilton (Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

The Bayrose Files by Diane Wald

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

In the 1980s, Boston journalist Violet Maris infiltrates the Provincetown Home for Artists and Writers, intending to write a juicy insider’s exposé of what goes on at this artists’ colony. But to get there she has to commit a deception. Her gay friend Spencer Bayrose has a whole sheaf of unpublished short stories drawing on his Louisiana upbringing, and he offers to let her submit them as her own work to get a place at PHAW. Here Violet finds eccentrics aplenty, and even romance, but when news comes that Spence has AIDS, she has to decide how far she’ll go for a story and what she owes her friend. At barely over 100 pages, this feels more like a long short story, one with a promising setting and a sound plot arc, but not enough time to get to know or particularly care about the characters. I was reminded of books I’ve read by Julia Glass and Sara Maitland. It’s offbeat and good-natured but not top tier.

Published by Regal House Publishing. With thanks to publicist Jackie Karneth of Books Forward for the advanced e-copy for review.

A Family Matter was the best of the bunch for me, followed closely by Dream State.

Which of these do you fancy reading?

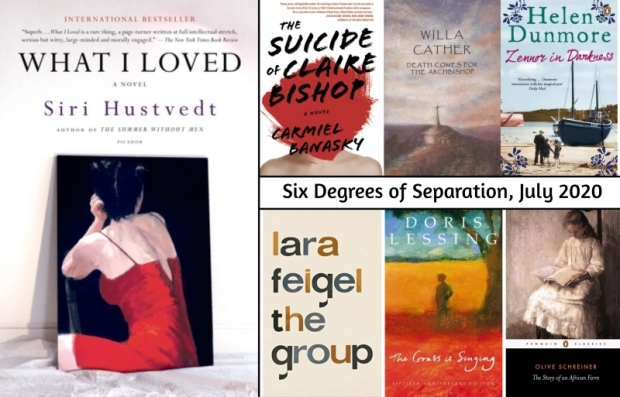

Six Degrees of Separation: From What I Loved to The Story of an African Farm

I’m a Six Degrees regular now: this is my sixth month taking part. This time (see Kate’s introductory post) we have all started with Siri Hustvedt’s What I Loved (2003). Narrated by a professor and set between the 1970s and 1990s, it’s about two New York City couples – academics and artists – and the losses they suffer over the years.

#1 The readalike I chose when I read What I Loved for a Valentine’s Day post in 2017 was The Suicide of Claire Bishop by Carmiel Banasky, which I’d covered for Foreword Reviews in 2015 (see here); it shares the themes of modern art and mental illness.

#1 The readalike I chose when I read What I Loved for a Valentine’s Day post in 2017 was The Suicide of Claire Bishop by Carmiel Banasky, which I’d covered for Foreword Reviews in 2015 (see here); it shares the themes of modern art and mental illness.

#2 Death + a “bishop” leads me to Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927), which vies with My Ántonia for the top spot from the six novels I’ve read so far by Willa Cather. It’s set in Santa Fe, New Mexico in the nineteenth century. I read it shortly after my trip to Santa Fe for the D.H. Lawrence Society of North America conference in the summer of 2005.

#3 Although I don’t think I’ve read a Lawrence novel in the past 15 years, I still enjoy reading about him, e.g. in Frieda by Annabel Abbs. My next biographical novel that includes DHL and his wife as characters will be Zennor in Darkness by Helen Dunmore (1994).

#4 Although it’s mostly set in London among university friends now in their late thirties or early forties, a few late scenes of The Group by Lara Feigel (brand new; I’ll be reviewing it in full later this month) are set in Zennor, Cornwall.

#5 The other book I’ve read by Lara Feigel is Free Woman, her bibliomemoir about marriage, motherhood and the works of Doris Lessing. My favorite of the six books I’ve read so far by Lessing is The Grass Is Singing (1950), set on a farm in Zimbabwe.

#6 The Story of an African Farm by Olive Schreiner (1883) is one of the novels I wrote about for my MA dissertation on female characters with unconventional religious views in the Victorian novel. In particular, I looked at the intersection of dissenting religious fiction and the “New Woman” novels that paved the way for Modernism. This is an obscure classic well worth picking up for its early feminist perspective; Schreiner was also a socialist and anti-war campaigner.

#6 The Story of an African Farm by Olive Schreiner (1883) is one of the novels I wrote about for my MA dissertation on female characters with unconventional religious views in the Victorian novel. In particular, I looked at the intersection of dissenting religious fiction and the “New Woman” novels that paved the way for Modernism. This is an obscure classic well worth picking up for its early feminist perspective; Schreiner was also a socialist and anti-war campaigner.

My chain has featured only books by women again this month: a few classics, a historical novel with real people in it, an updated modern classic (the Feigel – I’ll discuss its debt to Mary McCarthy’s The Group in my review), and more. The themes have included art, death, feminism, friendship, and religion.

Join us for #6Degrees of Separation if you haven’t already! Next month’s starting book is How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell.

Have you read any of my selections?

Are you tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Mini-Reviews of Three Recent Releases: Chariandy, Dean & Tallack

Brother by David Chariandy

Canadian author David Chariandy’s second novel was longlisted for the Giller Prize and won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. Narrator Michael and his older brother Francis grew up in the early 1980s in The Park, a slightly dodgy area of Toronto. Their single mother, Ruth, is a Trinidadian immigrant who worked long shifts as a cleaner to support the family after their father left early on. From the first pages we know that Francis is an absence, but don’t find out why until nearly the end of the book. The short novel is split between the present, as Michael and Ruth try to proceed with normal life, and vignettes from the past, culminating in the incident that took Francis from them 10 years ago.

Canadian author David Chariandy’s second novel was longlisted for the Giller Prize and won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. Narrator Michael and his older brother Francis grew up in the early 1980s in The Park, a slightly dodgy area of Toronto. Their single mother, Ruth, is a Trinidadian immigrant who worked long shifts as a cleaner to support the family after their father left early on. From the first pages we know that Francis is an absence, but don’t find out why until nearly the end of the book. The short novel is split between the present, as Michael and Ruth try to proceed with normal life, and vignettes from the past, culminating in the incident that took Francis from them 10 years ago.

The title is literal, of course, but also street slang for friends or comrades. Michael looked up to street-smart Francis, who fell in with a gang of “losers and neighbourhood schemers” and got expelled from school at age 18. Francis tried to teach his little brother how to carry himself: “You’ve got to be cooler about things, and not put everything out on your face all the time.” Yet the more we hear about Francis staying with friends at a barber shop and getting involved with preparations for a local rap DJ competition, the more his ideal of aloof masculinity starts to sound ironic, if not downright false.

I came into the book with pretty much no idea of what it was about. It didn’t fit my narrow expectations of Canadian fiction (sweeping prairie stories or hip city ones); instead, it reminded me of The Corner by David Simon, We, the Animals by Justin Torres, and Another Day in the Death of America by Gary Younge. It undoubtedly gives a powerful picture of immigrant poverty and complicated grief. Yet the measured prose somehow left me cold.

My rating:

Brother was published in the UK by Bloomsbury on March 8th. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Sharp by Michelle Dean

“People have trouble with women who aren’t ‘nice,’ … who have the courage to sometimes be wrong in public.” In compiling 10 mini-biographies of twentieth-century women writers and cultural critics who weren’t afraid to be unpopular, Dean (herself a literary critic) celebrates their feminist achievements and insists “even now … we still need more women like this.” Her subjects include Rebecca West, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron and Renata Adler. She draws on the women’s correspondence and published works as well as biographies to craft concise portraits of their personal and professional lives.

“People have trouble with women who aren’t ‘nice,’ … who have the courage to sometimes be wrong in public.” In compiling 10 mini-biographies of twentieth-century women writers and cultural critics who weren’t afraid to be unpopular, Dean (herself a literary critic) celebrates their feminist achievements and insists “even now … we still need more women like this.” Her subjects include Rebecca West, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron and Renata Adler. She draws on the women’s correspondence and published works as well as biographies to craft concise portraits of their personal and professional lives.

You’ll get the most out of this book if a) you know nothing about these women and experience this as a taster session; or b) you’re already interested in at least a few of them and are keen to learn more. I found the Dorothy Parker and Hannah Arendt chapters most interesting because, though I was familiar with their names, I knew very little about their lives or works. Parker’s writing was pulled from a slush pile in 1914 and she soon replaced P.G. Wodehouse as Vanity Fair’s drama critic. Her famous zingers masked her sadness over her dead parents and addict husband. “This was her gift,” Dean writes: “to shave complex emotions down to a witticism that hints at bitterness without wearing it on the surface.”

Unfortunately, such perceptive lines are few and far between, and the book as a whole lacks a thesis. Chance meetings between figures sometimes provide transitions, but the short linking chapters are oddly disruptive. In one, by arguing that Zora Neale Hurston would have done a better job covering a lynching than Rebecca West, Dean only draws attention to the homogeneity of her subjects: all white and middle-class; mostly Jewish New Yorkers. I knew too much about Sontag and Didion to find their chapters interesting, but enjoyed reading more about Ephron. I’ll keep the book to refer back to when I finally get around to reading Mary McCarthy. It has a terrific premise, but I found myself asking what the point was.

My rating:

Sharp was published in the UK by Fleet on May 3rd. My thanks to the publisher for a proof copy for review.

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack

I’d previously enjoyed Malachy Tallack’s two nonfiction books, Sixty Degrees North and The Undiscovered Islands. In his debut novel he returns to Shetland, where he spent some of his growing-up and early adult years, to sketch out a small community and the changes it undergoes over about ten months. Sandy has lived in this valley for three years with Emma, but she left him the day before the action opens. Unsure what to do now, he sticks around to help her father, David, butcher the lambs. After their 90-year-old neighbor, Maggie, dies, Sandy takes over her croft. Other valley residents include Ryan and Jo, a troubled young couple; Terry, a single dad; and Alice, who moved here after her husband’s death and is writing a human and natural history of the place, The Valley at the Centre of the World. (This strand reminded me of Annalena McAfee’s Hame.)

I’d previously enjoyed Malachy Tallack’s two nonfiction books, Sixty Degrees North and The Undiscovered Islands. In his debut novel he returns to Shetland, where he spent some of his growing-up and early adult years, to sketch out a small community and the changes it undergoes over about ten months. Sandy has lived in this valley for three years with Emma, but she left him the day before the action opens. Unsure what to do now, he sticks around to help her father, David, butcher the lambs. After their 90-year-old neighbor, Maggie, dies, Sandy takes over her croft. Other valley residents include Ryan and Jo, a troubled young couple; Terry, a single dad; and Alice, who moved here after her husband’s death and is writing a human and natural history of the place, The Valley at the Centre of the World. (This strand reminded me of Annalena McAfee’s Hame.)

The prose is reminiscent of the American plain-speaking style of books set in the South or Appalachia – Richard Ford, Walker Percy, Ron Rash and the like. We dive deep into this tight-knit community and its secrets. It’s an offbeat blend of primitive and modern: the minimalism of the crofting life contrasts with the global reach of Facebook, for instance. When Ryan and Jo host a housewarming party, all the characters are brought together at about the halfway point, and some relationships start to shift. Overall, though, this is a slow and meandering story. Don’t expect any huge happenings, just some touching reunions and terrific scenes of manual labor. David is my favorite character, an almost biblical patriarch who seems “to live in a kind of eternal present, looking neither forward nor backward but always, somehow, towards the land.”

Tallack has taken a risk by writing in phonetic Shetland dialect. David’s speech is particularly impenetrable. The dialect does rather intrude; the expository passages are a relief. I’ve been to Shetland once, in 2006. This quiet story of belonging versus being an outsider is one to reread there some years down the line: I reckon I’d appreciate it more on location.

My rating:

The Valley at the Centre of the World was published by Canongate on May 3rd. My thanks to the publisher for the free copy for review.

Stella, Kay, Helena, Polly and Priss met at a picnic while studying at Oxbridge and decided to rent a house together. Now 40-ish, they live in London and remain close, though their lives have branched in slightly different directions. Kay is an English teacher but has always wanted to be a novelist like her American husband, Harald. Priss is a stay-at-home mother excited to be opening a café. Polly, a gynaecological consultant at St Thomas’s Hospital, is having an affair with a married colleague. Helena, a single documentary presenter, decides she wants to have a baby and pursues insemination via a gay friend.

Stella, Kay, Helena, Polly and Priss met at a picnic while studying at Oxbridge and decided to rent a house together. Now 40-ish, they live in London and remain close, though their lives have branched in slightly different directions. Kay is an English teacher but has always wanted to be a novelist like her American husband, Harald. Priss is a stay-at-home mother excited to be opening a café. Polly, a gynaecological consultant at St Thomas’s Hospital, is having an affair with a married colleague. Helena, a single documentary presenter, decides she wants to have a baby and pursues insemination via a gay friend.

McCarthy focuses on eight girls from the Vassar class of ’33. Kay, the first to marry, has an upper-crust New York City wedding one week after graduation. But after Harald loses his theatre job, his cocktail habit and their luxury apartment soon deplete Kay’s Macy’s salary. Meanwhile, Dottie loses her virginity to Harald’s former neighbour in a surprisingly explicit scene. Contraception is complicated, but not without comic potential – as when Dottie confuses a pessary and a peccary. Career, romance, and motherhood are all fraught matters.

McCarthy focuses on eight girls from the Vassar class of ’33. Kay, the first to marry, has an upper-crust New York City wedding one week after graduation. But after Harald loses his theatre job, his cocktail habit and their luxury apartment soon deplete Kay’s Macy’s salary. Meanwhile, Dottie loses her virginity to Harald’s former neighbour in a surprisingly explicit scene. Contraception is complicated, but not without comic potential – as when Dottie confuses a pessary and a peccary. Career, romance, and motherhood are all fraught matters.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

A brother steals the main character’s object of affection in The Crow Road by Iain Banks and Sacred Country by Rose Tremain.

Everything Happens for a Reason, and Other Lies I’ve Loved by Kate Bowler: An assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, Bowler was fascinated by prosperity theology: the idea that God’s blessings reward righteous living and generous giving to the church. If she’d been tempted to set store by this notion, that certainty was permanently fractured when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in her mid-thirties. Bowler writes tenderly about suffering and surrender, and about living in the moment with her husband and son while being uncertain of the future, in a style reminiscent of Anne Lamott and Nina Riggs.

Everything Happens for a Reason, and Other Lies I’ve Loved by Kate Bowler: An assistant professor at Duke Divinity School, Bowler was fascinated by prosperity theology: the idea that God’s blessings reward righteous living and generous giving to the church. If she’d been tempted to set store by this notion, that certainty was permanently fractured when she was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in her mid-thirties. Bowler writes tenderly about suffering and surrender, and about living in the moment with her husband and son while being uncertain of the future, in a style reminiscent of Anne Lamott and Nina Riggs.

The Most Beautiful Thing I’ve Seen: Opening Your Eyes to Wonder by Lisa Gungor: Like many Gungor listeners, Lisa grew up in, and soon outgrew, a fundamentalist Christian setting. She married Michael Gungor at the absurdly young age of 19 and they struggled with infertility and world events. When their second daughter was born with Down syndrome and required urgent heart surgery, it sparked further soul searching and a return to God, but this time within a much more open spirituality that encircles and values everyone – her gay neighbors, her disabled daughter; the ones society overlooks.

The Most Beautiful Thing I’ve Seen: Opening Your Eyes to Wonder by Lisa Gungor: Like many Gungor listeners, Lisa grew up in, and soon outgrew, a fundamentalist Christian setting. She married Michael Gungor at the absurdly young age of 19 and they struggled with infertility and world events. When their second daughter was born with Down syndrome and required urgent heart surgery, it sparked further soul searching and a return to God, but this time within a much more open spirituality that encircles and values everyone – her gay neighbors, her disabled daughter; the ones society overlooks.

In the Days of Rain: A Daughter, a Father, a Cult by Rebecca Stott: This is several things: a bereavement memoir that opens with Stott’s father succumbing to cancer and eliciting her promise to finish his languishing memoirs; a family memoir tracking generations in England, Scotland and Australia; and a story of faith and doubt, of the absolute certainty experienced inside the Exclusive Brethren (a sect that numbers 45,000 worldwide) and how that cracked until there was no choice but to leave. Stott grew up with an apocalyptic mindset. It wasn’t until she was a teenager that she learned to trust her intellect and admit doubts.

In the Days of Rain: A Daughter, a Father, a Cult by Rebecca Stott: This is several things: a bereavement memoir that opens with Stott’s father succumbing to cancer and eliciting her promise to finish his languishing memoirs; a family memoir tracking generations in England, Scotland and Australia; and a story of faith and doubt, of the absolute certainty experienced inside the Exclusive Brethren (a sect that numbers 45,000 worldwide) and how that cracked until there was no choice but to leave. Stott grew up with an apocalyptic mindset. It wasn’t until she was a teenager that she learned to trust her intellect and admit doubts.

A River Could Be a Tree by Angela Himsel: From rural Indiana and an apocalyptic Christian cult to New York City and Orthodox Judaism by way of studies in Jerusalem: Himsel has made quite the religious leap. She was one of 11 children and grew up in the Worldwide Church of God (reminiscent of the Exclusive Brethren from Stott’s book). Although leaving a cult is easy to understand, what happens next feels more like a random sequence of events than a conscious choice; maybe I needed some more climactic scenes.

A River Could Be a Tree by Angela Himsel: From rural Indiana and an apocalyptic Christian cult to New York City and Orthodox Judaism by way of studies in Jerusalem: Himsel has made quite the religious leap. She was one of 11 children and grew up in the Worldwide Church of God (reminiscent of the Exclusive Brethren from Stott’s book). Although leaving a cult is easy to understand, what happens next feels more like a random sequence of events than a conscious choice; maybe I needed some more climactic scenes.  Why Religion? A Personal Story by Elaine Pagels: Pagels is a religion scholar known for her work on the Gnostic Gospels. As a teen she joined a friend’s youth group and answered the altar call at a Billy Graham rally. Although she didn’t stick with Evangelicalism, spirituality provided some comfort when her son died of pulmonary hypertension at age six and her physicist husband Heinz fell to his death on a hike in Colorado little more than a year later. She sees religion’s endurance as proof that it plays a necessary role in human life.

Why Religion? A Personal Story by Elaine Pagels: Pagels is a religion scholar known for her work on the Gnostic Gospels. As a teen she joined a friend’s youth group and answered the altar call at a Billy Graham rally. Although she didn’t stick with Evangelicalism, spirituality provided some comfort when her son died of pulmonary hypertension at age six and her physicist husband Heinz fell to his death on a hike in Colorado little more than a year later. She sees religion’s endurance as proof that it plays a necessary role in human life.  When I Spoke in Tongues: A Story of Faith and Its Loss by Jessica Wilbanks: Like me, Wilbanks grew up attending a Pentecostal-style church in southern Maryland. I recognized the emotional tumult of her trajectory – the lure of power and certainty; the threat of punishment and ostracism – as well as some of the specifics of her experience. Captivated by the story of Enoch Adeboye and his millions-strong Redemption Camps, she traveled to Nigeria to research the possible Yoruba roots of Pentecostalism in the summer of 2010.

When I Spoke in Tongues: A Story of Faith and Its Loss by Jessica Wilbanks: Like me, Wilbanks grew up attending a Pentecostal-style church in southern Maryland. I recognized the emotional tumult of her trajectory – the lure of power and certainty; the threat of punishment and ostracism – as well as some of the specifics of her experience. Captivated by the story of Enoch Adeboye and his millions-strong Redemption Camps, she traveled to Nigeria to research the possible Yoruba roots of Pentecostalism in the summer of 2010.  Not That Kind of Girl by Carlene Bauer: A bookish, introspective adolescent, Bauer was troubled by how fundamentalism denied the validity of secular art. All the same, Christian notions of purity and purpose stuck with her throughout her college days in Baltimore and then when she was trying to make it in publishing in New York City. Along the way she flirted with converting to Catholicism. What Bauer does best is to capture a fleeting mindset and its evolution into a broader way of thinking.

Not That Kind of Girl by Carlene Bauer: A bookish, introspective adolescent, Bauer was troubled by how fundamentalism denied the validity of secular art. All the same, Christian notions of purity and purpose stuck with her throughout her college days in Baltimore and then when she was trying to make it in publishing in New York City. Along the way she flirted with converting to Catholicism. What Bauer does best is to capture a fleeting mindset and its evolution into a broader way of thinking.  The Book of Separation by Tova Mirvis: In a graceful and painfully honest memoir, Mirvis goes back and forth in time to contrast the simplicity – but discontentment – of her early years of marriage with the disorientation she felt after divorcing her husband and leaving Orthodox Judaism. Anyone who has wrestled with faith or other people’s expectations will appreciate this story of finding the courage to be true to yourself.

The Book of Separation by Tova Mirvis: In a graceful and painfully honest memoir, Mirvis goes back and forth in time to contrast the simplicity – but discontentment – of her early years of marriage with the disorientation she felt after divorcing her husband and leaving Orthodox Judaism. Anyone who has wrestled with faith or other people’s expectations will appreciate this story of finding the courage to be true to yourself.  Between Gods by Alison Pick: At a time of transition – preparing for her wedding and finishing her first novel, set during her Holocaust – the author decided to convert to Judaism, the faith of her father’s Czech family. Ritual was her way into Judaism: she fasted for Yom Kippur and took her father to synagogue on the anniversary of her grandfather’s death, but also had the fun of getting ready for a Purim costume party.

Between Gods by Alison Pick: At a time of transition – preparing for her wedding and finishing her first novel, set during her Holocaust – the author decided to convert to Judaism, the faith of her father’s Czech family. Ritual was her way into Judaism: she fasted for Yom Kippur and took her father to synagogue on the anniversary of her grandfather’s death, but also had the fun of getting ready for a Purim costume party.  Post-Traumatic Church Syndrome: A Memoir of Humor and Healing by Reba Riley: Riley was a Pentecostal-leaning fundamentalist through high school, but turned her back on it in college. Yet she retained a strong spiritual compass that helped her tap into the energy of the “Godiverse.” She concocted the idea of experiencing 30 different religious traditions before she turned 30, and spent 2011–12 visiting a Hindu temple, a Buddhist meditation center, a mosque, a synagogue, a gathering of witches, and a range of Christian churches.

Post-Traumatic Church Syndrome: A Memoir of Humor and Healing by Reba Riley: Riley was a Pentecostal-leaning fundamentalist through high school, but turned her back on it in college. Yet she retained a strong spiritual compass that helped her tap into the energy of the “Godiverse.” She concocted the idea of experiencing 30 different religious traditions before she turned 30, and spent 2011–12 visiting a Hindu temple, a Buddhist meditation center, a mosque, a synagogue, a gathering of witches, and a range of Christian churches.  Girl Meets God: A Memoir by Lauren F. Winner: Some people just seem to have the religion gene. That’s definitely true of Winner, who was as enthusiastic an Orthodox Jew as she later was a Christian after the conversion that began in her college years. Like Anne Lamott, Winner draws on anecdotes from everyday life and very much portrays herself as a “bad Christian,” one who struggles with the basics like praying and finding a church community and is endlessly grateful for the grace that covers her shortcomings.

Girl Meets God: A Memoir by Lauren F. Winner: Some people just seem to have the religion gene. That’s definitely true of Winner, who was as enthusiastic an Orthodox Jew as she later was a Christian after the conversion that began in her college years. Like Anne Lamott, Winner draws on anecdotes from everyday life and very much portrays herself as a “bad Christian,” one who struggles with the basics like praying and finding a church community and is endlessly grateful for the grace that covers her shortcomings.  When We Were on Fire by Addie Zierman: Zierman was a poster girl for Evangelicalism in her high school years. After attending Christian college, she and her husband spent a lonely year teaching English in Pinghu, China. Things got worse before they got better, but eventually she made her way out of depression through therapy, antidepressants and EMDR treatments, marriage counselling, a dog, a home of their own, and – despite the many ways she’d been hurt and let down by “Church People” over the years – a good-enough church.

When We Were on Fire by Addie Zierman: Zierman was a poster girl for Evangelicalism in her high school years. After attending Christian college, she and her husband spent a lonely year teaching English in Pinghu, China. Things got worse before they got better, but eventually she made her way out of depression through therapy, antidepressants and EMDR treatments, marriage counselling, a dog, a home of their own, and – despite the many ways she’d been hurt and let down by “Church People” over the years – a good-enough church.  Fleeing Fundamentalism by Carlene Cross

Fleeing Fundamentalism by Carlene Cross

Not pictured: (on Nook) Girl at the End of the World by Elizabeth Esther; (on Kindle) Shunned by Linda A. Curtis and Cut Me Loose by Leah Vincent. Also, I got a copy of Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood for my birthday, but I’m not clear to what extent it’s actually about her religious experiences.

Not pictured: (on Nook) Girl at the End of the World by Elizabeth Esther; (on Kindle) Shunned by Linda A. Curtis and Cut Me Loose by Leah Vincent. Also, I got a copy of Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood for my birthday, but I’m not clear to what extent it’s actually about her religious experiences. On the Bright Side: The New Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen [Jan. 11, Michael Joseph (Penguin UK)]: I loved the first Hendrik Groen novel back in 2016 (reviewed

On the Bright Side: The New Secret Diary of Hendrik Groen [Jan. 11, Michael Joseph (Penguin UK)]: I loved the first Hendrik Groen novel back in 2016 (reviewed  Writer’s Luck: A Memoir: 1976–1991 by David Lodge [Jan. 11, Harvill Secker]: I reviewed the first volume of Lodge’s memoirs,

Writer’s Luck: A Memoir: 1976–1991 by David Lodge [Jan. 11, Harvill Secker]: I reviewed the first volume of Lodge’s memoirs,  Brass: A Novel by Xhenet Aliu (for BookBrowse review) [Jan. 23, Random House]: “A waitress at the Betsy Ross Diner, Elsie hopes her nickel-and-dime tips will add up to a new life. Then she meets Bashkim, … who left Albania to chase his dreams. … Told in equally gripping parallel narratives with biting wit and grace, Brass announces a fearless new voice with a timely, tender, and quintessentially American story.” (NetGalley download)

Brass: A Novel by Xhenet Aliu (for BookBrowse review) [Jan. 23, Random House]: “A waitress at the Betsy Ross Diner, Elsie hopes her nickel-and-dime tips will add up to a new life. Then she meets Bashkim, … who left Albania to chase his dreams. … Told in equally gripping parallel narratives with biting wit and grace, Brass announces a fearless new voice with a timely, tender, and quintessentially American story.” (NetGalley download) Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley [Jan. 25, Weidenfeld & Nicolson]: The “search for a cure [for chronic pain] takes her on a global quest, exploring the boundaries between science, psychology and faith with practitioners on the fringes of conventional, traditional and alternative medicine. Rais[es] vital questions about the modern medical system … and the struggle to retain a sense of self.” (print review copy)

Heal Me: In Search of a Cure by Julia Buckley [Jan. 25, Weidenfeld & Nicolson]: The “search for a cure [for chronic pain] takes her on a global quest, exploring the boundaries between science, psychology and faith with practitioners on the fringes of conventional, traditional and alternative medicine. Rais[es] vital questions about the modern medical system … and the struggle to retain a sense of self.” (print review copy) The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar [Jan. 25, Harvill Secker]: “A spellbinding story of curiosity, love and obsession from an astonishing new talent. One September evening in 1785, the merchant Jonah Hancock hears urgent knocking on his front door. One of his captains is waiting eagerly on the step. He has sold Jonah’s ship for what appears to be a mermaid.” Comes recommended by

The Mermaid and Mrs. Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar [Jan. 25, Harvill Secker]: “A spellbinding story of curiosity, love and obsession from an astonishing new talent. One September evening in 1785, the merchant Jonah Hancock hears urgent knocking on his front door. One of his captains is waiting eagerly on the step. He has sold Jonah’s ship for what appears to be a mermaid.” Comes recommended by  Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington [Feb. 6, Guardian Faber]: Darlington’s previous nature book, Otter Country, was stunning. Here, “Darlington sets out to tell a new story. Her fieldwork begins with wild encounters in the British Isles and takes her to the frosted borders of the Arctic. In her watching and deep listening to the natural world, she cleaves myth from reality and will change the way you think of this magnificent creature.”

Owl Sense by Miriam Darlington [Feb. 6, Guardian Faber]: Darlington’s previous nature book, Otter Country, was stunning. Here, “Darlington sets out to tell a new story. Her fieldwork begins with wild encounters in the British Isles and takes her to the frosted borders of the Arctic. In her watching and deep listening to the natural world, she cleaves myth from reality and will change the way you think of this magnificent creature.” The Grave’s a Fine and Private Place by Alan Bradley [Feb. 8, Orion]: I’ve read all eight Flavia de Luce novels so far, which is worth remarking on because I don’t otherwise read mysteries and I usually find child narrators annoying. There’s just something delicious about this series set in 1950s England. This one will be particularly interesting because a life-changing blow came at the end of the previous book.

The Grave’s a Fine and Private Place by Alan Bradley [Feb. 8, Orion]: I’ve read all eight Flavia de Luce novels so far, which is worth remarking on because I don’t otherwise read mysteries and I usually find child narrators annoying. There’s just something delicious about this series set in 1950s England. This one will be particularly interesting because a life-changing blow came at the end of the previous book. A Black Fox Running by Brian Carter [Feb. 8, Bloomsbury UK]: “A beautiful lost classic of nature writing” from 1981 that “sits alongside Tarka the Otter, Watership Down,” et al. “This is the story of Wulfgar, the dark-furred fox of Dartmoor, and of his nemesis, Scoble the trapper, in the seasons leading up to the pitiless winter of 1947. As breathtaking in its descriptions of the natural world as it is perceptive in its portrayal of damaged humanity.” Championed by Melissa Harrison.

A Black Fox Running by Brian Carter [Feb. 8, Bloomsbury UK]: “A beautiful lost classic of nature writing” from 1981 that “sits alongside Tarka the Otter, Watership Down,” et al. “This is the story of Wulfgar, the dark-furred fox of Dartmoor, and of his nemesis, Scoble the trapper, in the seasons leading up to the pitiless winter of 1947. As breathtaking in its descriptions of the natural world as it is perceptive in its portrayal of damaged humanity.” Championed by Melissa Harrison. White Houses by Amy Bloom [Feb. 13, Random House]: The story of Lorena Hickock’s friendship/affair with Eleanor Roosevelt. “From Washington, D.C. to Hyde Park, from a little white house on Long Island to an apartment on Manhattan’s Washington Square, Amy Bloom’s new novel moves elegantly through fascinating places and times, written in compelling prose and with emotional depth, wit, and acuity.” (Edelweiss download)

White Houses by Amy Bloom [Feb. 13, Random House]: The story of Lorena Hickock’s friendship/affair with Eleanor Roosevelt. “From Washington, D.C. to Hyde Park, from a little white house on Long Island to an apartment on Manhattan’s Washington Square, Amy Bloom’s new novel moves elegantly through fascinating places and times, written in compelling prose and with emotional depth, wit, and acuity.” (Edelweiss download) The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman [Feb. 20, Riverrun/Viking]: I’m a huge fan of Rachman’s, especially his previous novel, The Rise & Fall of Great Powers. “1955: The artists are gathering together for a photograph. In one of Rome’s historic villas, a party is bright with near-genius, shaded by the socialite patrons of their art. … Rachman displays a nuanced understanding of twentieth-century art and its demons, vultures and chimeras.” (Edelweiss download)

The Italian Teacher by Tom Rachman [Feb. 20, Riverrun/Viking]: I’m a huge fan of Rachman’s, especially his previous novel, The Rise & Fall of Great Powers. “1955: The artists are gathering together for a photograph. In one of Rome’s historic villas, a party is bright with near-genius, shaded by the socialite patrons of their art. … Rachman displays a nuanced understanding of twentieth-century art and its demons, vultures and chimeras.” (Edelweiss download) The Sea Beast Takes a Lover: Stories by Michael Andreasen [Feb. 27, Dutton (Penguin Group)]: “Romping through the fantastic with big-hearted ease, these stories cut to the core of what it means to navigate family, faith, and longing, whether in the form of a lovesick kraken slowly dragging a ship of sailors into the sea [or] a small town euthanizing its grandfathers in a time-honored ritual.” (NetGalley download)

The Sea Beast Takes a Lover: Stories by Michael Andreasen [Feb. 27, Dutton (Penguin Group)]: “Romping through the fantastic with big-hearted ease, these stories cut to the core of what it means to navigate family, faith, and longing, whether in the form of a lovesick kraken slowly dragging a ship of sailors into the sea [or] a small town euthanizing its grandfathers in a time-honored ritual.” (NetGalley download) The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist: A True Story of Injustice in the American South by Radley Balko and Tucker Carrington [Feb. 27, PublicAffairs]: “After two three-year-old girls were raped and murdered in rural Mississippi, law enforcement pursued and convicted two innocent men, [who] spent a combined thirty years in prison before finally being exonerated in 2008. Meanwhile, the real killer remained free.”

The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist: A True Story of Injustice in the American South by Radley Balko and Tucker Carrington [Feb. 27, PublicAffairs]: “After two three-year-old girls were raped and murdered in rural Mississippi, law enforcement pursued and convicted two innocent men, [who] spent a combined thirty years in prison before finally being exonerated in 2008. Meanwhile, the real killer remained free.” The Gospel of Trees: A Memoir by Apricot Irving [March 6, Simon & Schuster]: “Apricot Irving grew up as a missionary’s daughter in Haiti—a country easy to sensationalize but difficult to understand. Her father was an agronomist, a man who hiked alone into the hills … to preach the gospel of trees in a deforested but resilient country. Her mother and sisters, meanwhile, spent most of their days in the confines of the hospital compound they called home. As a child, this felt like paradise; as a teenager, the same setting felt like a prison.”

The Gospel of Trees: A Memoir by Apricot Irving [March 6, Simon & Schuster]: “Apricot Irving grew up as a missionary’s daughter in Haiti—a country easy to sensationalize but difficult to understand. Her father was an agronomist, a man who hiked alone into the hills … to preach the gospel of trees in a deforested but resilient country. Her mother and sisters, meanwhile, spent most of their days in the confines of the hospital compound they called home. As a child, this felt like paradise; as a teenager, the same setting felt like a prison.” The Little Book of Feminist Saints by Julia Pierpont (illus. by Manjitt Thapp) [March 6, Random House]: This project reminds me a lot of

The Little Book of Feminist Saints by Julia Pierpont (illus. by Manjitt Thapp) [March 6, Random House]: This project reminds me a lot of  Orchid Summer: In Search of the Wildest Flowers of the British Isles by Jon Dunn [March 8, Bloomsbury UK]: Dunn’s were my favorite contributions to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies (e.g.

Orchid Summer: In Search of the Wildest Flowers of the British Isles by Jon Dunn [March 8, Bloomsbury UK]: Dunn’s were my favorite contributions to the Wildlife Trusts’ Seasons anthologies (e.g.  Anatomy of a Miracle by Jonathan Miles [March 13, Hogarth]: Miles’s previous novel, Want Not, is one of the books I most wish I’d written. “Rendered paraplegic after a traumatic event, Cameron Harris has been living his new existence alongside his sister, Tanya, in their battered Biloxi, Mississippi neighborhood where only half the houses made it through Katrina. … [A] stunning exploration of faith, science, mystery, and the meaning of life.”

Anatomy of a Miracle by Jonathan Miles [March 13, Hogarth]: Miles’s previous novel, Want Not, is one of the books I most wish I’d written. “Rendered paraplegic after a traumatic event, Cameron Harris has been living his new existence alongside his sister, Tanya, in their battered Biloxi, Mississippi neighborhood where only half the houses made it through Katrina. … [A] stunning exploration of faith, science, mystery, and the meaning of life.” Happiness by Aminatta Forna [March 16, Grove Atlantic]: “London. A fox makes its way across Waterloo Bridge. The distraction causes two pedestrians to collide—Jean, an American studying the habits of urban foxes, and Attila, a Ghanaian psychiatrist there to deliver a keynote speech. … Forna’s unerring powers of observation show how in the midst of the rush of a great city lie numerous moments of connection.” (NetGalley download)

Happiness by Aminatta Forna [March 16, Grove Atlantic]: “London. A fox makes its way across Waterloo Bridge. The distraction causes two pedestrians to collide—Jean, an American studying the habits of urban foxes, and Attila, a Ghanaian psychiatrist there to deliver a keynote speech. … Forna’s unerring powers of observation show how in the midst of the rush of a great city lie numerous moments of connection.” (NetGalley download) The Long Forgotten by David Whitehouse [March 22, Pan Macmillan/Picador]: “When the black box flight recorder of a plane that went missing 30 years ago is found at the bottom of the sea, a young man named Dove begins to remember a past that isn’t his. The memories belong to a rare flower hunter in 1980s New York, whose search led him around the world and ended in tragedy.” (NetGalley download)

The Long Forgotten by David Whitehouse [March 22, Pan Macmillan/Picador]: “When the black box flight recorder of a plane that went missing 30 years ago is found at the bottom of the sea, a young man named Dove begins to remember a past that isn’t his. The memories belong to a rare flower hunter in 1980s New York, whose search led him around the world and ended in tragedy.” (NetGalley download) The Parentations by Kate Mayfield (to review for Shiny New Books?) [March 29, Oneworld]: From editor Jenny Parrott: “a stunning speculative historical novel … The story spans 200 years across Iceland and London, as a strange boy who can never die is surrounded by a motley collection of individuals, each with vested interests in his welfare. … [S]ome of the most extraordinary literary prose I’ve read during a thirty-year career.”

The Parentations by Kate Mayfield (to review for Shiny New Books?) [March 29, Oneworld]: From editor Jenny Parrott: “a stunning speculative historical novel … The story spans 200 years across Iceland and London, as a strange boy who can never die is surrounded by a motley collection of individuals, each with vested interests in his welfare. … [S]ome of the most extraordinary literary prose I’ve read during a thirty-year career.” Things Bright and Beautiful by Anbara Salam [April 5, Fig Tree]: “1954, the South Pacific islands. When Beatriz Hanlon agreed to accompany her missionary husband Max to a remote island, she knew there would be challenges. But it isn’t just the heat and the damp and the dirt. There are more insects than she could ever have imagined, and the islanders are strangely hostile. [Then] an unexpected … guest arrives, and the couple’s claustrophobic existence is stretched to breaking point.” Sounds like Euphoria by Lily King. (NetGalley download)

Things Bright and Beautiful by Anbara Salam [April 5, Fig Tree]: “1954, the South Pacific islands. When Beatriz Hanlon agreed to accompany her missionary husband Max to a remote island, she knew there would be challenges. But it isn’t just the heat and the damp and the dirt. There are more insects than she could ever have imagined, and the islanders are strangely hostile. [Then] an unexpected … guest arrives, and the couple’s claustrophobic existence is stretched to breaking point.” Sounds like Euphoria by Lily King. (NetGalley download) Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion by Michelle Dean [April 10, Grove Press]: “Dorothy Parker, Rebecca West, Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Pauline Kael, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron, Renata Adler, and Janet Malcolm—these brilliant women’s lives intertwine as they cut through the cultural and intellectual history of America in the twentieth century, arguing as fervently with each other as they did with the sexist attitudes of the men who often undervalued their work as critics and essayists.”

Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion by Michelle Dean [April 10, Grove Press]: “Dorothy Parker, Rebecca West, Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy, Susan Sontag, Pauline Kael, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron, Renata Adler, and Janet Malcolm—these brilliant women’s lives intertwine as they cut through the cultural and intellectual history of America in the twentieth century, arguing as fervently with each other as they did with the sexist attitudes of the men who often undervalued their work as critics and essayists.” The Plant Messiah: Adventures in Search of the World’s Rarest Species by Carlos Magdalena [April 10, Doubleday]: “Carlos Magdalena is not your average horticulturist. He’s a man on a mission to save the world’s most endangered plants. … [He] takes readers from the Amazon to the jungles of Mauritius. … Back in the lab, we watch as he develops groundbreaking, left-field techniques for rescuing species from extinction, encouraging them to propagate and thrive once again.” (NetGalley download)

The Plant Messiah: Adventures in Search of the World’s Rarest Species by Carlos Magdalena [April 10, Doubleday]: “Carlos Magdalena is not your average horticulturist. He’s a man on a mission to save the world’s most endangered plants. … [He] takes readers from the Amazon to the jungles of Mauritius. … Back in the lab, we watch as he develops groundbreaking, left-field techniques for rescuing species from extinction, encouraging them to propagate and thrive once again.” (NetGalley download) The Man on the Middle Floor by Elizabeth S. Moore (for blog tour) [April 12, RedDoor Publishing]: “Despite living in the same three-flat house in the suburbs of London, the residents are strangers to one another. … They have lived their lives separately, until now, when an unsolved murder and the man on the middle floor connect them. … It questions whether society is meeting the needs of the fast growing autistic section of society.” (print ARC)

The Man on the Middle Floor by Elizabeth S. Moore (for blog tour) [April 12, RedDoor Publishing]: “Despite living in the same three-flat house in the suburbs of London, the residents are strangers to one another. … They have lived their lives separately, until now, when an unsolved murder and the man on the middle floor connect them. … It questions whether society is meeting the needs of the fast growing autistic section of society.” (print ARC) Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan [April 24, Random House UK]: “This is a love letter to the joys of childhood reading, full of enthusiasm and wit, telling the colorful story of our best-loved children’s books, the extraordinary people who created them, and the thousand subtle ways they shape our lives.” (NetGalley download)

Bookworm: A Memoir of Childhood Reading by Lucy Mangan [April 24, Random House UK]: “This is a love letter to the joys of childhood reading, full of enthusiasm and wit, telling the colorful story of our best-loved children’s books, the extraordinary people who created them, and the thousand subtle ways they shape our lives.” (NetGalley download) You Think It, I’ll Say It: Stories by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 24, Random House]: I would read anything Curtis Sittenfeld wrote; American Wife is still one of my absolute favorites. “The theme that unites these stories … is how even the cleverest people tend to misread others, and how much we all deceive ourselves. Sharp and tender, funny and wise, this collection shows [her] knack for creating real, believable characters that spring off the page.”

You Think It, I’ll Say It: Stories by Curtis Sittenfeld [April 24, Random House]: I would read anything Curtis Sittenfeld wrote; American Wife is still one of my absolute favorites. “The theme that unites these stories … is how even the cleverest people tend to misread others, and how much we all deceive ourselves. Sharp and tender, funny and wise, this collection shows [her] knack for creating real, believable characters that spring off the page.” The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack [May 3, Canongate]: I’ve reviewed and enjoyed both of Tallack’s previous nonfiction works, including

The Valley at the Centre of the World by Malachy Tallack [May 3, Canongate]: I’ve reviewed and enjoyed both of Tallack’s previous nonfiction works, including  Shapeshifters: A Journey through the Changing Human Body by Gavin Francis [May 8, Basic Books]: “Francis considers the inevitable changes all of our bodies undergo—such as birth, puberty, and death, but also … those that only some of our bodies will: like getting a tattoo, experiencing psychosis, suffering anorexia, being pregnant, or undergoing a gender transition. … [E]ach event becomes an opportunity to explore the meaning of identity.”

Shapeshifters: A Journey through the Changing Human Body by Gavin Francis [May 8, Basic Books]: “Francis considers the inevitable changes all of our bodies undergo—such as birth, puberty, and death, but also … those that only some of our bodies will: like getting a tattoo, experiencing psychosis, suffering anorexia, being pregnant, or undergoing a gender transition. … [E]ach event becomes an opportunity to explore the meaning of identity.” The Ensemble by Aja Gabel [May 15, Riverhead]: An “addictive debut novel about four young friends navigating the cutthroat world of music and their complex relationships with each other, as ambition, passion, and love intertwine over the course of their lives.”

The Ensemble by Aja Gabel [May 15, Riverhead]: An “addictive debut novel about four young friends navigating the cutthroat world of music and their complex relationships with each other, as ambition, passion, and love intertwine over the course of their lives.” Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? by Lev Parikian (for blog tour) [May 17, Unbound]: “A lapsed and hopeless birdwatcher’s attempt to see 200 birds in a year. But it’s not just about birds. It’s about family, music, nostalgia; hearing the stories of strangers; the nature of obsession and obsession with nature.”

Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear? by Lev Parikian (for blog tour) [May 17, Unbound]: “A lapsed and hopeless birdwatcher’s attempt to see 200 birds in a year. But it’s not just about birds. It’s about family, music, nostalgia; hearing the stories of strangers; the nature of obsession and obsession with nature.” The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai [June 19, Viking]: I loved both of Makkai’s previous novels and have her short story collection on my Kindle. “Fiona is in Paris tracking down her estranged daughter, who disappeared into a cult. While staying with an old friend, a famous photographer …, she finds herself finally grappling with the devastating ways the AIDS crisis affected her life and her relationship with her daughter.” (Edelweiss download)

The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai [June 19, Viking]: I loved both of Makkai’s previous novels and have her short story collection on my Kindle. “Fiona is in Paris tracking down her estranged daughter, who disappeared into a cult. While staying with an old friend, a famous photographer …, she finds herself finally grappling with the devastating ways the AIDS crisis affected her life and her relationship with her daughter.” (Edelweiss download) #2. There are two “Madame Bovarys” before the one we’re interested in.

#2. There are two “Madame Bovarys” before the one we’re interested in.