Poetry Review Catch-up: Burch, Carrick-Varty, Davidson, Marya, Parsons (#ReadIndies)

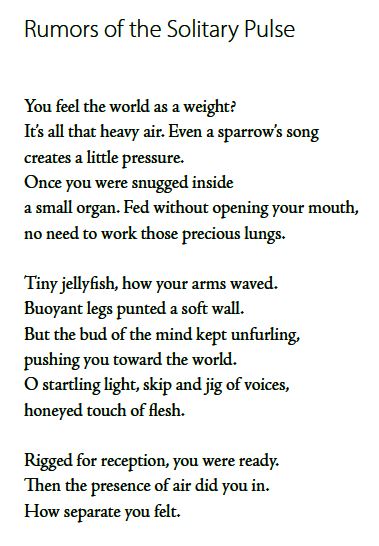

As Read Indies month continues, I’m catching up on poetry collections I’ve been sent by three independent publishers: the UK’s Carcanet Press, and Alice James Books and Terrapin Press, both based in the USA. Various as these five are in style and technique, nature and family ties are linking themes. From each I’ve chosen one short poem as a representative.

Leave Me a Little Want by Beverly Burch (2022)

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

Burch’s fourth collection juxtaposes the cosmic and the mundane, marvelling at the behind-the-scenes magic that goes into one human being born but also making poetry of an impatient wait in a long post office queue. We find weather and travel; smell as well as sight and sound; alliteration and internal rhyme. Beset by environmental anxiety and the scale of bad news during the pandemic, she pauses in appreciation of the small and gradual. Often nature teaches these lessons. “Practice slow. Days for a seed to unfurl a shoot, / yawn out true leaves. Stems creep upward like prayers. / Weeks to make a flower, more to shape fruit.” Burch expresses gratitude for what is and what has been: a man carrying an infant outside her kitchen window gives her a pang for the baby days, but when she puts her hunting cat on house arrest she realizes how glad she is that impulsivity is past: “Intensity. More subtle than passion. / Odd to be grateful so much of my life is over.” Each section contains multiple unrhymed sonnets, as well as an “incantation” and/or an exploration of “Ars Poetica”.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

More Sky by Joe Carrick-Varty (2023)

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

In this debut collection by an Eric Gregory Award-winning poet, his father’s suicide is ever-present – and not just in poems like “54 Questions for the Man Who Sold a Shotgun to My Father” but in seemingly unrelated pieces that start off being about something else. Everything comes around to the reality of a neglectful, alcoholic father and the sordid flat he inhabited before his death. Carrick-Varty alternates between an intimate “you” address and third-person scenarios, auditioning coping mechanisms. His frame of reference is wide: football, rappers, Buddhist cosmology. Some poems are printed sideways up the page; there are stanzas, paragraphs and columns. The word “suicide” itself is repeated to the point where it loses meaning, becoming just a sibilant collection of syllables (as in “From the Perspective of Coral,” where “suicide” is substituted for sea creatures, or the long culminating poem, “sky doc,” in which every stanza opens with “Once upon a time when suicide was…”) The tone is often bitter, as is to be expected, but there is joy in the deft use of language.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free e-copy for review.

Arctic Elegies by Peter Davidson (2022)

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Much of the verse in Davidson’s second collection draws on British religious history and liturgy. Some is also in conversation with art, music or other poetry. In all of these cases, I found the Notes at the end of the volume invaluable for understanding the context and inspiration. While most are in stanzas, some employing traditional forms (e.g., “Sonnet for Trinity Sunday”), a few of the poems are in paragraphs and feel more like essays, such as “Secret Theatres of Scotland.” As the title heralds, an elegiac tone runs throughout, with “Arctic Elegy” (taking material from an oratorio he wrote for performance in St Andrew’s Cathedral in 2015) dedicated to the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845–8:

Wonderful is the patience of the snow

And glorious the violence of the cold.

How lovely is the power of the dark pole

To draw the iron and move the compass rose.

As cold as loss as cold as freezing steel

In this same vein, I also appreciated the wry “The Museum of Loss” and the ornate “The Mourning Virtuoso.” There’s a bit of an Auden flavour here, but the niche topics didn’t always hold my attention.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the free copy for review.

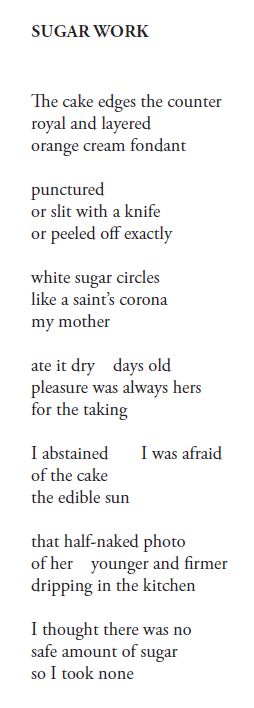

Sugar Work by Katie Marya (2022)

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

Marya’s debut collection contains frank autobiographical poems about growing up in Atlanta and Las Vegas with a single mother who was a sex worker and an absentee father. As the pages turn, she gets her first period, loses her virginity, marries and divorces. Her childhood persists in photographs, and the details of places, foods and pop culture form the recognizable texture of American suburbia. Social media haunts or taunts: that photo her addict father posts every year on Facebook of him holding her, aged three, on a beach; the Instagram perfection she wishes she could attain. Marya’s phrasing is carnal, unsentimental and in-your-face (viz. “Valentine’s Day: “Do you think love only exists / because death exists? / I do not want to marry you. // But I do want explosions / of white taffeta and a cake / propped up in my mouth // with your hand for a photo. / Skin is a casing and I hook / mine to yours with a needle.”) There is also a feminist determination to see justice for women who are abused and accused.

With thanks to Alyson Sinclair PR for the free e-copy for review.

The Mayapple Forest by Kim Ports Parsons (2022)

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

Parts of this alliteration-rich debut collection respond to the pandemic’s gifts of time and attention. Gardening and baking, two of the activities that sustained so many people during lockdowns, appear as acts of faith – planting seeds and waiting to see what becomes of them – and acts of remembrance (in “The Poetry of Pie,” she’s a child making peach pie with her mother). There is a fresh awareness of nature, especially birds: starlings, a bluebird nest, the lovely portrait in “Barn Owl.” From the forest floor to the stars, this world is full of wonders. Human stories thread through, too: dancing to soul music, fixing an elderly woman’s hair, the layers of history uncovered during a renovation of her childhood home. Contrasting with her temporary residence in the Midwest is her nostalgia for Baltimore. Parsons reflects on the sudden loss of her father (“A quick death’s a blessing / for the one who dies”) and the still-tender absence of her mother, the book’s dedicatee.

With thanks to Terrapin Books for the free e-copy for review.

Read any good poetry recently?

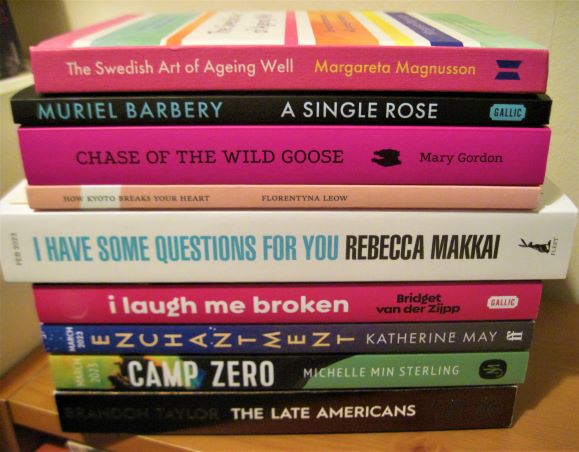

The 2023 Releases I’ve Read So Far

Some reviewers and book bloggers are constantly reading three to six months ahead of what’s out on the shelves, but I tend to get behind on proof copies and read from the library instead. (Who am I kidding? I’m no influencer.)

In any case, I happen to have read a number of pre-release books, generally for paid review for Foreword, Shelf Awareness, etc. Most of my reviews haven’t been published yet; I’ll give very brief excerpts and ratings here to pique the interest.

Early in January I’ll follow up with my 20 Most Anticipated titles of the coming year.

My top recommendations so far:

(In alphabetical order)

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman [Feb. 28, Kernpunkt Press]: Sixteen sumptuous historical stories ranging from flash to novella length depict outsiders and pioneers who face disability and prejudice with poise.

Shoot the Horses First by Leah Angstman [Feb. 28, Kernpunkt Press]: Sixteen sumptuous historical stories ranging from flash to novella length depict outsiders and pioneers who face disability and prejudice with poise.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland [April 4, Simon & Schuster]: Four characters – two men and two women; two white people and two Black slaves – are caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. Painstakingly researched and a propulsive read.

The House Is on Fire by Rachel Beanland [April 4, Simon & Schuster]: Four characters – two men and two women; two white people and two Black slaves – are caught up in the Richmond Theater Fire of 1811. Painstakingly researched and a propulsive read.

Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe [March 7, Akashic Books]: A high school girl’s basketball coach and a Black poet, both survivors of a conversion therapy camp in Oregon, return to the site of their spiritual abuse, looking for redemption.

Tell the Rest by Lucy Jane Bledsoe [March 7, Akashic Books]: A high school girl’s basketball coach and a Black poet, both survivors of a conversion therapy camp in Oregon, return to the site of their spiritual abuse, looking for redemption.

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer [April 4, Hub City Press]: A pensive memoir investigates the blinking lights that appeared in his family’s woods soon after his mother’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in 2019.

All of Us Together in the End by Matthew Vollmer [April 4, Hub City Press]: A pensive memoir investigates the blinking lights that appeared in his family’s woods soon after his mother’s death from complications of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in 2019.

Other 2023 releases I’ve read:

(In publication date order; links to the few reviews that are already available online)

Pusheen the Cat’s Guide to Everything by Claire Belton [Jan. 10, Gallery Books]: Good-natured and whimsical comic scenes delight in the endearing quirks of Pusheen, everyone’s favorite cartoon cat since Garfield. Belton creates a family and pals for her, too.

Pusheen the Cat’s Guide to Everything by Claire Belton [Jan. 10, Gallery Books]: Good-natured and whimsical comic scenes delight in the endearing quirks of Pusheen, everyone’s favorite cartoon cat since Garfield. Belton creates a family and pals for her, too.

Everything’s Changing by Chelsea Stickle [Jan. 13, Thirty West]: The 20 weird flash fiction stories in this chapbook are like prizes from a claw machine: you never know whether you’ll pluck a drunk raccoon or a red onion the perfect size to replace a broken heart.

Everything’s Changing by Chelsea Stickle [Jan. 13, Thirty West]: The 20 weird flash fiction stories in this chapbook are like prizes from a claw machine: you never know whether you’ll pluck a drunk raccoon or a red onion the perfect size to replace a broken heart.

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph [Jan. 17, Alice James Books]: With formal variety and thematic intensity, this second collection by the Philippines-born poet ruminates on her protracted recovery from a traumatic car accident and her journey to U.S. citizenship.

Decade of the Brain by Janine Joseph [Jan. 17, Alice James Books]: With formal variety and thematic intensity, this second collection by the Philippines-born poet ruminates on her protracted recovery from a traumatic car accident and her journey to U.S. citizenship.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie [Jan. 19, Bloomsbury]: Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie [Jan. 19, Bloomsbury]: Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on.

The Faraway World by Patricia Engel [Jan. 24, Simon & Schuster]: These 10 short stories contrast dreams and reality. Money and religion are opposing pulls for Latinx characters as they ponder whether life will be better at home or elsewhere.

The Faraway World by Patricia Engel [Jan. 24, Simon & Schuster]: These 10 short stories contrast dreams and reality. Money and religion are opposing pulls for Latinx characters as they ponder whether life will be better at home or elsewhere.

Your Hearts, Your Scars by Adina Talve-Goodman [Jan. 24, Bellevue Literary Press]: The author grew up a daughter of rabbis in St. Louis and had a heart transplant at age 19. This posthumous collection gathers seven poignant autobiographical essays about living joyfully and looking for love in spite of chronic illness.

Your Hearts, Your Scars by Adina Talve-Goodman [Jan. 24, Bellevue Literary Press]: The author grew up a daughter of rabbis in St. Louis and had a heart transplant at age 19. This posthumous collection gathers seven poignant autobiographical essays about living joyfully and looking for love in spite of chronic illness.

God’s Ex-Girlfriend: A Memoir About Loving and Leaving the Evangelical Jesus by Gloria Beth Amodeo [Feb. 21, Ig Publishing]: In a candid memoir, Amodeo traces how she was drawn into Evangelical Christianity in college before coming to see it as a “common American cult” involving unhealthy relationship dynamics and repressed sexuality.

God’s Ex-Girlfriend: A Memoir About Loving and Leaving the Evangelical Jesus by Gloria Beth Amodeo [Feb. 21, Ig Publishing]: In a candid memoir, Amodeo traces how she was drawn into Evangelical Christianity in college before coming to see it as a “common American cult” involving unhealthy relationship dynamics and repressed sexuality.

Zig-Zag Boy: A Memoir of Madness and Motherhood by Tanya Frank [Feb. 28, W. W. Norton]: A wrenching debut memoir ranges between California and England and draws in metaphors of the natural world as it recounts a decade-long search to help her mentally ill son.

Zig-Zag Boy: A Memoir of Madness and Motherhood by Tanya Frank [Feb. 28, W. W. Norton]: A wrenching debut memoir ranges between California and England and draws in metaphors of the natural world as it recounts a decade-long search to help her mentally ill son.

The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore [March 7, The University of North Carolina Press]: An Iowan now based in Oregon, Moore balances nostalgia and critique to craft nuanced, hypnotic autobiographical essays about growing up in the Midwest. The piece on Shania Twain is a highlight.

The Distance from Slaughter County by Steven Moore [March 7, The University of North Carolina Press]: An Iowan now based in Oregon, Moore balances nostalgia and critique to craft nuanced, hypnotic autobiographical essays about growing up in the Midwest. The piece on Shania Twain is a highlight.

Currently reading:

(In release date order)

My What If Year: A Memoir by Alisha Fernandez Miranda [Feb. 7, Zibby Books]: “On the cusp of turning forty, Alisha Fernandez Miranda … decides to give herself a break, temporarily pausing her stressful career as the CEO of her own consulting firm … she leaves her home in London to spend one year exploring the dream jobs of her youth.”

My What If Year: A Memoir by Alisha Fernandez Miranda [Feb. 7, Zibby Books]: “On the cusp of turning forty, Alisha Fernandez Miranda … decides to give herself a break, temporarily pausing her stressful career as the CEO of her own consulting firm … she leaves her home in London to spend one year exploring the dream jobs of her youth.”

Sea Change by Gina Chung [April 11, Vintage]: “With her best friend pulling away to focus on her upcoming wedding, Ro’s only companion is Dolores, a giant Pacific octopus who also happens to be Ro’s last remaining link to her father, a marine biologist who disappeared while on an expedition when Ro was a teenager.”

Sea Change by Gina Chung [April 11, Vintage]: “With her best friend pulling away to focus on her upcoming wedding, Ro’s only companion is Dolores, a giant Pacific octopus who also happens to be Ro’s last remaining link to her father, a marine biologist who disappeared while on an expedition when Ro was a teenager.”

Additional pre-release books on my shelf:

(In release date order)

Will you look out for one or more of these?

Any 2023 reads you can recommend already?

Short Nature Books for #NovNov by John Burnside, Jim Crumley and Aimee Nezhukumatathil

#NovNov meets #NonfictionNovember as nonfiction week of Novellas in November continues!

Tomorrow I’ll post my review of our buddy read for the week, The Story of My Life by Helen Keller (free from Project Gutenberg, here).

Today I review four nature books that celebrate marvelous but threatened creatures and ponder our place in relation to them.

Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction by John Burnside (2021)

[127 pages]

I’ve read a novel, a memoir, and several poetry collections by Burnside. He’s a multitalented author who’s written in many different genres. These four essays are rich with allusions and chewy with philosophical questions. “Aurochs” traces ancient bulls from the classical world onward and notes the impossibility of entering others’ subjectivity – true for other humans, so how much more so for extinct animals. Imagination and empathy are required. Burnside recounts an incident from when he went to visit his former partner’s family cattle farm in Gloucestershire and a poorly cow fell against his legs. Sad as he felt for her, he couldn’t help.

I’ve read a novel, a memoir, and several poetry collections by Burnside. He’s a multitalented author who’s written in many different genres. These four essays are rich with allusions and chewy with philosophical questions. “Aurochs” traces ancient bulls from the classical world onward and notes the impossibility of entering others’ subjectivity – true for other humans, so how much more so for extinct animals. Imagination and empathy are required. Burnside recounts an incident from when he went to visit his former partner’s family cattle farm in Gloucestershire and a poorly cow fell against his legs. Sad as he felt for her, he couldn’t help.

“Auks” tells the story of how we drove the Great Auk to extinction and likens it to whaling, two tragic cases of exploiting species for our own ends. The second and fourth essays stood out most to me. “The hint half guessed, the gift half understood” links literal species extinction with the loss of a sense of place. The notion of ‘property’ means that land becomes a space to be filled. Contrast this with places devoid of time and ownership, like Chernobyl. Although I appreciated the discussion of solastalgia and ecological grief, much of the material here felt a rehashing of my other reading, such as Footprints, Islands of Abandonment, Irreplaceable, Losing Eden and Notes from an Apocalypse. Some Covid references date this one in an unfortunate way, while the final essay, “Blossom Ruins,” has a good reason for mentioning Covid-19: Burnside was hospitalized for it in April 2020, his near-death experience a further spur to contemplate extinction and false hope.

The academic register and frequent long quotations from other thinkers may give other readers pause. Those less familiar with current environmental nonfiction will probably get more out of these essays than I did, though overall I found them worth engaging with.

With thanks to Little Toller Books for the proof copy for review.

Kingfisher and Otter by Jim Crumley (2018)

[59 pages each]

Part of Crumley’s “Encounters in the Wild” series for the publisher Saraband, these are attractive wee hardbacks with covers by Carry Akroyd. (I’ve previously reviewed his The Company of Swans.) Each is based on the Scottish nature writer’s observations and serendipitous meetings, while an afterword gives additional information on the animal and its appearances in legend and literature.

An unexpected link between these two volumes was beavers, now thriving in Scotland after a recent reintroduction. Crumley marvels that, 400 years after their kind could last have interacted with beavers, otters have quickly gotten used to sharing rivers – to him this “suggests that race memory is indestructible.” Likewise, kingfishers gravitate to where beaver dams have created fish-filled ponds.

Kingfisher was, marginally, my preferred title from the pair. It sticks close to one spot, a particular “bend in the river” where the author watches faithfully and is occasionally rewarded by the sight of one or two kingfishers. As the book opens, he sees what at first looks like a small brown bird flying straight at him, until the head-on view becomes a profile that reveals a flash of electric blue. As the Gerard Manley Hopkins line has it (borrowed for the title of Alex Preston’s book on birdwatching), kingfishers “catch fire.” Lyrical writing and self-deprecating honesty about the necessity of waiting (perhaps in the soaking rain) for moments of magic made this a lovely read. “Colour is to kingfishers what slipperiness is to eels. … Vanishing and theory-shattering are what kingfishers do best.”

In Otter, Crumley ranges a bit more widely, prioritizing outlying Scottish islands from Shetland to Skye. It’s on Mull that he has the best views, seeing four otters in one day, though “no encounter is less than unforgettable.” He watches them playing with objects and tries to talk back to them by repeating their “Haah?” sound. “Everything I gather from familiar landscapes is more precious as a beholder, as a nature writer, because my own constant presence in that landscape is also a part of the pattern, and I reclaim the ancient right of my own species to be part of nature myself.”

From time to time we see a kingfisher flying down the canal. Some of our neighbors have also seen an otter swimming across from the end of the gardens, but despite our dusk vigils we haven’t been so lucky as to see one yet. I’ve only seen a wild otter once, at Ham Wall Nature Reserve in Somerset. One day, maybe there will be one right here in my backyard. (Public library)

World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks and Other Astonishments by Aimee Nezhukumatathil (2020)

[160 pages]

Nezhukumatathil, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi, published four poetry collections before she made a splash with this beautifully illustrated collection of brief musings on species and the self – this was shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize. Some of the 28 pieces spotlight an animal simply for how head-shakingly wondrous it is, like the dancing frog or the cassowary. More often, though, a creature or plant is a figurative vehicle for uncovering an aspect of her past. An example: “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun. Don’t get too dark … our mother would remind us as we ambled out into the relentless midwestern light.”

Nezhukumatathil, a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Mississippi, published four poetry collections before she made a splash with this beautifully illustrated collection of brief musings on species and the self – this was shortlisted for the Kirkus Prize. Some of the 28 pieces spotlight an animal simply for how head-shakingly wondrous it is, like the dancing frog or the cassowary. More often, though, a creature or plant is a figurative vehicle for uncovering an aspect of her past. An example: “A catalpa can give two brown girls in western Kansas a green umbrella from the sun. Don’t get too dark … our mother would remind us as we ambled out into the relentless midwestern light.”

The author’s Indian/Filipina family moved frequently for her mother’s medical jobs, and sometimes they were the only brown people around. Loneliness, the search for belonging and a compulsion to blend in are thus recurrent themes. As an adult, traveling for poetry residencies and sabbaticals exposes her to new species like whale sharks. Childhood trips back to India allowed her to spend time among peacocks, her favorite animal. In the American melting pot, her elementary school drawing of a peacock was considered unacceptable, but when she featured a bald eagle and flag instead she won a prize.

These pinpricks of the BIPOC experience struck me more powerfully than the actual nature writing, which can be shallow and twee. Talking to birds, praising the axolotl’s “smile,” directly addressing the reader – it’s all very nice, but somewhat uninformed; while she does admit to sadness and worry about what we are losing, her sunny outlook seemed out of touch at times. On the one hand, it’s great that she wanted to structure her fragments of memoir around amazing animals; on the other, I suspect that it cheapens a species to only consider it as a metaphor for the self (a vampire squid or potoo = her desire to camouflage herself in high school; flamingos = herself and other fragile long-legged college students; a bird of paradise = the guests dancing the Macarena at her wedding reception).

My favorite pieces were one on the corpse flower and the bookend duo on fireflies – she hits just the right note of nostalgia and warning: “I know I will search for fireflies all the rest of my days, even though they dwindle a little bit more each year. I can’t help it. They blink on and off, a lime glow to the summer night air, as if to say, I am still here, you are still here.”

With thanks to Souvenir Press for the free copy for review.

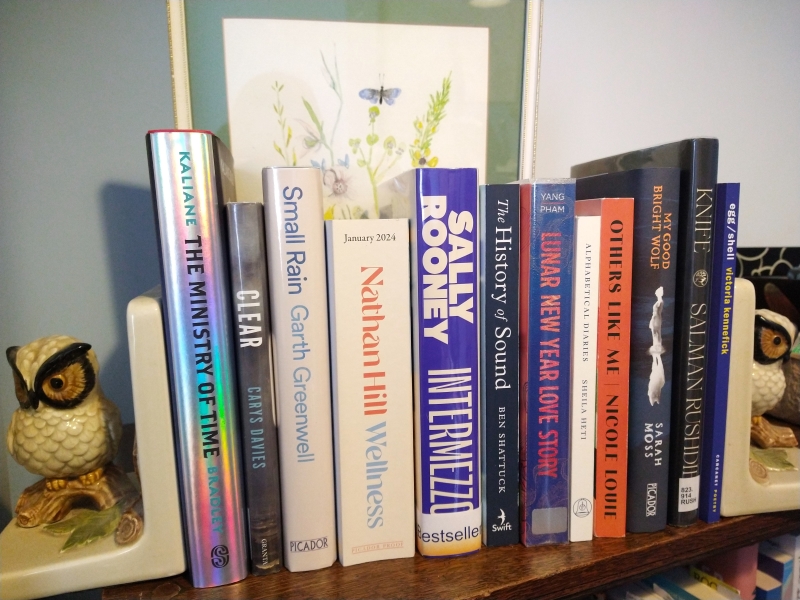

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Small Rain by Garth Greenwell: A poet and academic (who both is and is not Greenwell) endures a Covid-era medical crisis that takes him to the brink of mortality and the boundary of survivable pain. Over two weeks, we become intimately acquainted with his every test, intervention, setback and fear. Experience is clarified precisely into fluent language that also flies far above a hospital bed, into a vibrant past, a poetic sensibility, a hoped-for normality. I’ve never read so remarkable an account of what it is to be a mind in a fragile body.

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”):

Dorothy Caliban is a California housewife whose unhappy marriage to Fred has been strained by the death of their young son (an allergic reaction during routine surgery) and a later miscarriage. When we read that Dorothy believes the radio has started delivering personalized messages to her, we can’t then be entirely sure if its news report about a dangerous creature escaped from an oceanographic research centre is real or a manifestation of her mental distress. Even when the 6’7” frog-man, Larry, walks into her kitchen and becomes her lover and secret lodger, I had to keep asking myself: is he ever independently seen by another character? Can these actions be definitively attributed to him? So perhaps this is a novella to experience on two levels. Take it at face value and it’s a lighthearted caper of duelling adulterers and revenge, with a pointed message about the exploitation of the Other. Or interpret it as a midlife fantasy of sexual rejuvenation and an attentive partner (“[Larry] said that he enjoyed housework. He was good at it and found it interesting”): I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]

I hadn’t heard of the author but picked this up from the Bestseller display in my library. It’s a posthumous collection of writings, starting with a few articles Boas wrote for his local newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, about his experience of terminal illness. Diagnosed late on with incurable throat cancer, Boas spent his last year smoking and drinking Muscadet. Looking back at the privilege and joys of his life, he knew he couldn’t complain too much about dying at 46. He had worked in charitable relief in wartorn regions, finishing his career as director of Jersey Overseas Aid. The articles are particularly witty. After learning his cancer had metastasized to his lungs, he wrote, “The prognosis is not quite ‘Don’t buy any green bananas’, but it’s pretty close to ‘Don’t start any long books’.” While I admired the perspective and equanimity of the other essays, most of their topics were overly familiar for me (gratitude, meditation, therapy, what (not) to do/say to the dying). His openness to religion and use of psychedelics were a bit more interesting. It’s hard to write anything original about dying, and his determined optimism – to the extent of downplaying the environmental crisis – grated. (Public library) [138 pages]  I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:

I’ve reviewed one of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s books for a previous NovNov:  I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

I was always going to read this because I’m a big fan of Susan Allen Toth’s work, including her trilogy of cosy

There are 22 stories in this fairly short book, so most top out at no more than 10 pages: little slices of life on and around the reservation at Spokane, Washington. Some central characters recur, such as Victor, Thomas Builds-the-Fire and James Many Horses, but there are so many tales that I couldn’t keep track of them across the book even though I read it quickly. My favourite was “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona,” in which Victor and Thomas fly out to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Some of the longer titles give a sense of the tone: “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” and “Jesus Christ’s Half-Brother Is Alive and Well on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” I couldn’t help but think of it as a so-so rehearsal for

There are 22 stories in this fairly short book, so most top out at no more than 10 pages: little slices of life on and around the reservation at Spokane, Washington. Some central characters recur, such as Victor, Thomas Builds-the-Fire and James Many Horses, but there are so many tales that I couldn’t keep track of them across the book even though I read it quickly. My favourite was “This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona,” in which Victor and Thomas fly out to collect the ashes of Victor’s father. Some of the longer titles give a sense of the tone: “Because My Father Always Said He Was the Only Indian Who Saw Jimi Hendrix Play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock” and “Jesus Christ’s Half-Brother Is Alive and Well on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” I couldn’t help but think of it as a so-so rehearsal for  The title story is about Mary Toft – I thought of making her hoax the subject of a Three on a Theme post because I actually have two novels about her downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss (Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer), but the facts as conveyed here don’t seem like nearly enough to fuel a whole book, so I doubt I’ll read those. Donoghue has a good eye for historical curios and incidents and an academic’s gift for research, yet not many of these 17 stories, most of which are in the third person, rise above the novelty. Many protagonists are British or Irish women who were a footnote in the historical record: an animal rights activist, a lord’s daughter, a cult leader, a blind poet, a medieval rioter, a suspected witch. There are mild homoerotic touches, too. I enjoyed “Come, Gentle Night,” about John Ruskin’s honeymoon, and “Cured,” which reveals a terrifying surgical means of controlling women’s moods but, as I found with Astray and Learned by Heart, Donoghue sometimes lets documented details overwhelm other elements of a narrative. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)

The title story is about Mary Toft – I thought of making her hoax the subject of a Three on a Theme post because I actually have two novels about her downloaded from NetGalley and Edelweiss (Mary and the Rabbit Dream by Noémi Kiss-Deáki and Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen by Dexter Palmer), but the facts as conveyed here don’t seem like nearly enough to fuel a whole book, so I doubt I’ll read those. Donoghue has a good eye for historical curios and incidents and an academic’s gift for research, yet not many of these 17 stories, most of which are in the third person, rise above the novelty. Many protagonists are British or Irish women who were a footnote in the historical record: an animal rights activist, a lord’s daughter, a cult leader, a blind poet, a medieval rioter, a suspected witch. There are mild homoerotic touches, too. I enjoyed “Come, Gentle Night,” about John Ruskin’s honeymoon, and “Cured,” which reveals a terrifying surgical means of controlling women’s moods but, as I found with Astray and Learned by Heart, Donoghue sometimes lets documented details overwhelm other elements of a narrative. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com)  Hard to convey the variety of this 20-story anthology in a concise way because they run the gamut from realist (Nigerian homosexuality in “Happy Is a Doing Word” by Arinze Ifeakandu; Irish gangsters in “The Blackhills” by Eamon McGuinness) to absurd (Ling Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Catherine Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal; “Ira and the Whale” is Rachel B. Glaser’s gay version of the Jonah legend). Also difficult to encapsulate my reaction, because for every story I would happily have seen expanded into a novel (the gloomy character study “The Locksmith” by Grey Wolfe LaJoie, the teenage friends’ coming-of-age in “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool” by the marvellous Kirstin Valdez Quade), there was another I thought might never end (“Dream Man” by Cristina Rivera-Garza and “Temporary Housing” by Kathleen Alcott). Three are in translation. I admired Lisa Taddeo’s tale of grief and revenge, “Wisconsin,” and Naomi Shuyama-Gómez’s creepy Colombian-set “The Commander’s Teeth.” But my two favourites were probably “Me, Rory, and Aurora” by Jonas Eika (Danish), which combines an uneasy threesome, the plight of the unhoused and a downright chilling Ishiguro-esque ending; and “Xífù,” K-Ming Chang’s funny, morbid take on daughter/mother-in-law relations in China. (PDF review copy)

Hard to convey the variety of this 20-story anthology in a concise way because they run the gamut from realist (Nigerian homosexuality in “Happy Is a Doing Word” by Arinze Ifeakandu; Irish gangsters in “The Blackhills” by Eamon McGuinness) to absurd (Ling Ma’s “Office Hours” has academics passing through closet doors into a dream space; the title of Catherine Lacey’s “Man Mountain” is literal; “Ira and the Whale” is Rachel B. Glaser’s gay version of the Jonah legend). Also difficult to encapsulate my reaction, because for every story I would happily have seen expanded into a novel (the gloomy character study “The Locksmith” by Grey Wolfe LaJoie, the teenage friends’ coming-of-age in “After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool” by the marvellous Kirstin Valdez Quade), there was another I thought might never end (“Dream Man” by Cristina Rivera-Garza and “Temporary Housing” by Kathleen Alcott). Three are in translation. I admired Lisa Taddeo’s tale of grief and revenge, “Wisconsin,” and Naomi Shuyama-Gómez’s creepy Colombian-set “The Commander’s Teeth.” But my two favourites were probably “Me, Rory, and Aurora” by Jonas Eika (Danish), which combines an uneasy threesome, the plight of the unhoused and a downright chilling Ishiguro-esque ending; and “Xífù,” K-Ming Chang’s funny, morbid take on daughter/mother-in-law relations in China. (PDF review copy)  The novel-in-stories is about Lucy, a photographer in her early thirties with a penchant for falling for the wrong men – alcoholics or misogynists or ones who aren’t available. When she’s not working she’s thrill-seeking: rafting in Colorado, travelling in the Amazon, sailing in the Caribbean, or gliding. “Everything good I’ve gotten in life I’ve gotten by plunging in,” she boasts, to which a friend replies, “Sure, and everything bad you’ve gotten in your life you’ve gotten by plunging in.” Ultimately she ‘settles down’ on the Colorado ranch she inherits from her grandmother with a dog, making this – based on what I learned from the autobiographical essays in

The novel-in-stories is about Lucy, a photographer in her early thirties with a penchant for falling for the wrong men – alcoholics or misogynists or ones who aren’t available. When she’s not working she’s thrill-seeking: rafting in Colorado, travelling in the Amazon, sailing in the Caribbean, or gliding. “Everything good I’ve gotten in life I’ve gotten by plunging in,” she boasts, to which a friend replies, “Sure, and everything bad you’ve gotten in your life you’ve gotten by plunging in.” Ultimately she ‘settles down’ on the Colorado ranch she inherits from her grandmother with a dog, making this – based on what I learned from the autobiographical essays in  McCracken is terrific in short forms:

McCracken is terrific in short forms:  Compared to

Compared to  These 44 stories, mostly of flash fiction length, combine the grit of Denis Johnson with the bite of Flannery O’Connor. Siblings squabble over a late parent’s effects or wishes, marriages go wrong, the movie business isn’t as glittering as it’s cracked up to be, and drugs and alcohol complicate everything. The settings range through North America and the Caribbean, with a couple of forays to Europe. There are no speech marks and, whether the narrative is in first person or third, all the voices are genuine and distinctive yet flow together admirably. Svoboda has a poet-like talent for compact, zingy lines; two favourites were “my laziness is born of generalized-looking-to-get-specific grief, like an atom trying to make salt” (“Niagara”) and “Ditziness, a kind of Morse code of shriek-and-stop, erupts around the girls” (“Orphan Shop”).

These 44 stories, mostly of flash fiction length, combine the grit of Denis Johnson with the bite of Flannery O’Connor. Siblings squabble over a late parent’s effects or wishes, marriages go wrong, the movie business isn’t as glittering as it’s cracked up to be, and drugs and alcohol complicate everything. The settings range through North America and the Caribbean, with a couple of forays to Europe. There are no speech marks and, whether the narrative is in first person or third, all the voices are genuine and distinctive yet flow together admirably. Svoboda has a poet-like talent for compact, zingy lines; two favourites were “my laziness is born of generalized-looking-to-get-specific grief, like an atom trying to make salt” (“Niagara”) and “Ditziness, a kind of Morse code of shriek-and-stop, erupts around the girls” (“Orphan Shop”).  I’d only ever read The Color Purple, so when I spotted this in a bookshop on our Northumberland holiday it felt like a good excuse to try something else by Walker. I had actually encountered one of the stronger stories before: “Everyday Use” is in the

I’d only ever read The Color Purple, so when I spotted this in a bookshop on our Northumberland holiday it felt like a good excuse to try something else by Walker. I had actually encountered one of the stronger stories before: “Everyday Use” is in the  This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

This was a great collection of 33 stories, all of them beginning with the words “One Dollar” and most of flash fiction length. Bruce has a knack for quickly introducing a setup and protagonist. The voice and setting vary enough that no two stories sound the same. What is the worth of a dollar? In some cases, where there’s a more contemporary frame of reference, a dollar is a sign of desperation (for the man who’s lost house, job and wife in “Little Jimmy,” for the coupon-cutting penny-pincher whose unbroken monologue makes up the whole of “Grocery List”), or maybe just enough for a small treat for a child (as in “Mouse Socks” or “Boogie Board”). In the historical stories, a dollar can buy a lot more. It’s a tank of gas – and a lesson on the evils of segregation – in “Gas Station”; it’s a huckster’s exorbitant charge for a mocked-up relic in “The Grass Jesus Walked On.”

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths.

Taking a long walk through London one day, Khaled looks back from midlife on the choices he and his two best friends have made. He first came to the UK as an eighteen-year-old student at Edinburgh University. Everything that came after stemmed from one fateful day. Matar places Khaled and his university friend Mustafa at a real-life demonstration outside the Libyan embassy in London in 1984, which ended in a rain of bullets and the accidental death of a female police officer. Khaled’s physical wound is less crippling than the sense of being cut off from his homeland and his family. As he continues his literary studies and begins teaching, he decides to keep his injury a secret from them, as from nearly everyone else in his life. On a trip to Paris to support a female friend undergoing surgery, he happens to meet Hosam, a writer whose work enraptured him when he heard it on the radio back home long ago. Decades pass and the Arab Spring prompts his friends to take different paths. A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was

A second problem: Covid-19 stories feel dated. For the first two years of the pandemic I read obsessively about it, mostly nonfiction accounts from healthcare workers or ordinary people looking for community or turning to nature in a time of collective crisis. But now when I come across it as a major element in a book, it feels like an out-of-place artefact; I’m almost embarrassed for the author: so sorry, but you missed your moment. My disappointment may primarily be because my expectations were so high. I’ve noted that two blogger friends new to Nunez were enthusiastic about this (but so was  From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

From one November to the next, he watches the seasons advance and finds many magical spaces with everyday wonders to appreciate. “This project was already beginning to challenge my assumptions of what was beautiful or natural in the landscape,” he writes in his second week. True, he also finds distressing amounts of litter, no-access signs and evidence of environmental degradation. But curiosity is his watchword: “The more I pay attention, the more I notice. The more I notice, the more I learn.”

Apart from a few third-person segments about the parents, the chapters, set between 1997 and 2005, trade off first-person narration duties between Zora, a romantic would-be writer, and Sasha, the black sheep and substitute family storyteller-in-chief, who dates women and goes by Ashes when she starts wearing a binder. It’s interesting to discover examples of queer erasure in both parents’ past, connecting Beatrice more tightly to Sasha than it first appears – people always condemn most vehemently what they’re afraid of revealing in themselves.

Apart from a few third-person segments about the parents, the chapters, set between 1997 and 2005, trade off first-person narration duties between Zora, a romantic would-be writer, and Sasha, the black sheep and substitute family storyteller-in-chief, who dates women and goes by Ashes when she starts wearing a binder. It’s interesting to discover examples of queer erasure in both parents’ past, connecting Beatrice more tightly to Sasha than it first appears – people always condemn most vehemently what they’re afraid of revealing in themselves.

Asher and Ivan, two characters of nebulous sexuality and future gender, are the core of “Cheerful Until Next Time” (check out the acronym), which has the fantastic opening line “The queer feminist book club came to an end.” “Laramie Time” stars a lesbian couple debating whether to have a baby (in the comic Leigh draws, a turtle wishes “reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary”). “A Fearless Moral Inventory” features a pansexual who is a recovering sex addict. Adolescent girls are the focus in “The Black Winter of New England” and “Ooh, the Suburbs,” where they experiment with making lesbian leanings public and seeking older role models. “Pioneer,” probably my second favorite, has Coco pushing against gender constraints at a school Oregon Trail reenactment. Refusing to be a matriarch and not allowed to play a boy, she rebels by dressing up as an ox instead. The tone is often bleak or yearning, so “Counselor of My Heart” stands out as comic even though it opens with the death of a dog; Molly’s haplessness somehow feels excusable.

Asher and Ivan, two characters of nebulous sexuality and future gender, are the core of “Cheerful Until Next Time” (check out the acronym), which has the fantastic opening line “The queer feminist book club came to an end.” “Laramie Time” stars a lesbian couple debating whether to have a baby (in the comic Leigh draws, a turtle wishes “reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary”). “A Fearless Moral Inventory” features a pansexual who is a recovering sex addict. Adolescent girls are the focus in “The Black Winter of New England” and “Ooh, the Suburbs,” where they experiment with making lesbian leanings public and seeking older role models. “Pioneer,” probably my second favorite, has Coco pushing against gender constraints at a school Oregon Trail reenactment. Refusing to be a matriarch and not allowed to play a boy, she rebels by dressing up as an ox instead. The tone is often bleak or yearning, so “Counselor of My Heart” stands out as comic even though it opens with the death of a dog; Molly’s haplessness somehow feels excusable. Laskey inhabits all 11 personae with equal skill and compassion. Avery, the task force leader’s daughter, resents having to leave L.A. and plots an escape with her new friend Zach, a persecuted gay teen. Christine, a Christian homemaker, is outraged about the liberal agenda, whereas her bereaved neighbor, Linda, finds purpose and understanding in volunteering at the AAA office. Food hygiene inspector Henry is thrown when his wife leaves him for a woman, and meat-packing maven Lizzie agonizes over the question of motherhood. Task force members David, Tegan and Harley all have their reasons for agreeing to the project, but some characters have to sacrifice more than others.

Laskey inhabits all 11 personae with equal skill and compassion. Avery, the task force leader’s daughter, resents having to leave L.A. and plots an escape with her new friend Zach, a persecuted gay teen. Christine, a Christian homemaker, is outraged about the liberal agenda, whereas her bereaved neighbor, Linda, finds purpose and understanding in volunteering at the AAA office. Food hygiene inspector Henry is thrown when his wife leaves him for a woman, and meat-packing maven Lizzie agonizes over the question of motherhood. Task force members David, Tegan and Harley all have their reasons for agreeing to the project, but some characters have to sacrifice more than others. Four of the nine are holiday-themed, so this could make a good Twixtmas read if you like seasonality; eight are in the third person and just one has alternating first person narrators. All are what could be broadly dubbed romances, with most involving meet-cutes or moments when long-time friends realize their feelings go deeper (“Midnights” and “The Snow Ball”). Only one of the pairings is queer, however: Baz and Simon (who are a vampire and … a dragon-man, I think? and the subjects of a trilogy) in the Harry Potter-meets Twilight-meets Heartstopper “Snow for Christmas.” The rest are pretty straightforward boy-girl stories.

Four of the nine are holiday-themed, so this could make a good Twixtmas read if you like seasonality; eight are in the third person and just one has alternating first person narrators. All are what could be broadly dubbed romances, with most involving meet-cutes or moments when long-time friends realize their feelings go deeper (“Midnights” and “The Snow Ball”). Only one of the pairings is queer, however: Baz and Simon (who are a vampire and … a dragon-man, I think? and the subjects of a trilogy) in the Harry Potter-meets Twilight-meets Heartstopper “Snow for Christmas.” The rest are pretty straightforward boy-girl stories. This terrific Great Depression-era story was inspired by the real-life work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange who were sent by the Farm Security Administration, a new U.S. federal agency, to document the privations of the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. John Clark, 22, is following in his father’s footsteps as a photographer, leaving New York City to travel to the Oklahoma panhandle. He quickly discovers that struggling farmers are believed to have brought the drought on themselves through unsustainable practices. Many are fleeing to California. The locals are suspicious of John as an outsider, especially when they learn that he is working to a checklist (“Orphaned children”, “Family packing car to leave”).

This terrific Great Depression-era story was inspired by the real-life work of photographers such as Dorothea Lange who were sent by the Farm Security Administration, a new U.S. federal agency, to document the privations of the Dust Bowl in the Midwest. John Clark, 22, is following in his father’s footsteps as a photographer, leaving New York City to travel to the Oklahoma panhandle. He quickly discovers that struggling farmers are believed to have brought the drought on themselves through unsustainable practices. Many are fleeing to California. The locals are suspicious of John as an outsider, especially when they learn that he is working to a checklist (“Orphaned children”, “Family packing car to leave”).

This debut poetry collection is on the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist. I’ve noted that recent winners – such as

This debut poetry collection is on the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist. I’ve noted that recent winners – such as

I approached this as a companion to

I approached this as a companion to  A medical crisis during pregnancy that had her minutes from death was a wake-up call for Scull, leading her to rethink whether the life she was living was the one she wanted. She spent the next decade interviewing people in her New Zealand and the UK about what they learned when facing death. Some of the pieces are like oral histories (with one reprinted from a blog), while others involve more of an imagining of the protagonist’s past and current state of mind. Each is given a headline that encapsulates a threat to contentment, such as “Not Having a Good Work–Life Balance” and “Not Following Your Gut Instinct.” Most of her subjects are elderly or terminally ill. She also speaks to two chaplains, one a secular humanist working in a hospital and the other an Anglican priest based at a hospice, who recount some of the regrets they hear about through patients’ stories.

A medical crisis during pregnancy that had her minutes from death was a wake-up call for Scull, leading her to rethink whether the life she was living was the one she wanted. She spent the next decade interviewing people in her New Zealand and the UK about what they learned when facing death. Some of the pieces are like oral histories (with one reprinted from a blog), while others involve more of an imagining of the protagonist’s past and current state of mind. Each is given a headline that encapsulates a threat to contentment, such as “Not Having a Good Work–Life Balance” and “Not Following Your Gut Instinct.” Most of her subjects are elderly or terminally ill. She also speaks to two chaplains, one a secular humanist working in a hospital and the other an Anglican priest based at a hospice, who recount some of the regrets they hear about through patients’ stories.