Four for #NonfictionNovember and #NovNov25: Hanff, Humphrey, Kimmerer & Steinbeck

I’ll be doubling up posts most days for the rest of this month to cram everything in!

Today I have a cosy companion story to a beloved bibliophiles’ classic, a comprehensive account of my favourite beverage, a refreshing Indigenous approach to economics, and a journalistic exposé that feels nearly as relevant now as it did 90 years ago.

Q’s Legacy by Helene Hanff (1985)

Of course we all know and love 84, Charing Cross Road, about Hanff’s epistolary friendship with the staff of Marks & Co. Antiquarian Booksellers in London in the 1950s. This gives a bit of background to the writing and publication of that book, responds to its unexpected success, and follows up on a couple of later trips to England for the TV and stage adaptations. Hanff lived in a tiny New York City apartment and worked behind the scenes in theatre and television. Even authoring a cult classic didn’t change the facts of being a creative in one of the world’s most expensive cities: paying the bills between royalty checks was a scramble. The title is a little odd and refers to Hanff’s self-directed education after she had to leave Temple University after a year. When she stumbled on Cambridge professor Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch’s books of lectures at the library, she decided to make them the basis of her classical education. I most liked the diary from a 1970s trip to London on which she stayed in her UK publisher André Deutsch’s mother’s apartment! This is pleasant and I appreciated Hanff’s humble delight in her unexpected later-life accomplishments, but it does feel rather like a collection of scraps. I also have to wonder to what extent this repeats content from the 84 sequel, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street. But if you’ve liked her other books, you may as well read this one, too. (Free – The Book Thing of Baltimore) [177 pages]

Of course we all know and love 84, Charing Cross Road, about Hanff’s epistolary friendship with the staff of Marks & Co. Antiquarian Booksellers in London in the 1950s. This gives a bit of background to the writing and publication of that book, responds to its unexpected success, and follows up on a couple of later trips to England for the TV and stage adaptations. Hanff lived in a tiny New York City apartment and worked behind the scenes in theatre and television. Even authoring a cult classic didn’t change the facts of being a creative in one of the world’s most expensive cities: paying the bills between royalty checks was a scramble. The title is a little odd and refers to Hanff’s self-directed education after she had to leave Temple University after a year. When she stumbled on Cambridge professor Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch’s books of lectures at the library, she decided to make them the basis of her classical education. I most liked the diary from a 1970s trip to London on which she stayed in her UK publisher André Deutsch’s mother’s apartment! This is pleasant and I appreciated Hanff’s humble delight in her unexpected later-life accomplishments, but it does feel rather like a collection of scraps. I also have to wonder to what extent this repeats content from the 84 sequel, The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street. But if you’ve liked her other books, you may as well read this one, too. (Free – The Book Thing of Baltimore) [177 pages] ![]()

Gin by Shonna Milliken Humphrey (2020)

Picking up something from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series (or any of these other series of nonfiction books) is a splendid way to combine two challenges. Humphrey was introduced to gin at 16 when the manager of the movie theater where she worked gave her Pepsi cups of gin and grapefruit juice. Luckily, that didn’t precede any kind of misconduct and she’s been fond of gin ever since. She takes readers through the etymology of gin (from the Dutch genever; I startled the bartender by ordering a glass of neat vieux ginèvre at a bar in Brussels in September), the single necessary ingredient (juniper), the distillation process, the varieties (single- or double-distilled; Old Tom with sugar added), the different neutral spirits or grain bases that can be used (at a recent tasting I had gins made from apples and potatoes), and appearances in popular culture from William Hogarth’s preachy prints through The African Queen and James Bond to rap music. I found plenty of interesting tidbits – Samuel Pepys mentions gin (well, “strong water made of juniper,” anyway) in his diary as a constipation cure – but the writing is nothing special, I knew a lot of technical details from distillery tours, and I would have liked more exploration of the modern gin craze. “Gin is, in many ways, how I see myself: comfortable, but evolving,” Humphrey writes. “Gin has always interested a younger generation of drinker, as well as commitment from the older crowd, while maintaining a reputation among the middle aged. It is unique that way.” That checks out from my experience of tastings and the fact that it’s my mother-in-law’s tipple of choice as well. (Birthday gift from my Bookshop wish list) [134 pages]

Picking up something from the Bloomsbury Object Lessons series (or any of these other series of nonfiction books) is a splendid way to combine two challenges. Humphrey was introduced to gin at 16 when the manager of the movie theater where she worked gave her Pepsi cups of gin and grapefruit juice. Luckily, that didn’t precede any kind of misconduct and she’s been fond of gin ever since. She takes readers through the etymology of gin (from the Dutch genever; I startled the bartender by ordering a glass of neat vieux ginèvre at a bar in Brussels in September), the single necessary ingredient (juniper), the distillation process, the varieties (single- or double-distilled; Old Tom with sugar added), the different neutral spirits or grain bases that can be used (at a recent tasting I had gins made from apples and potatoes), and appearances in popular culture from William Hogarth’s preachy prints through The African Queen and James Bond to rap music. I found plenty of interesting tidbits – Samuel Pepys mentions gin (well, “strong water made of juniper,” anyway) in his diary as a constipation cure – but the writing is nothing special, I knew a lot of technical details from distillery tours, and I would have liked more exploration of the modern gin craze. “Gin is, in many ways, how I see myself: comfortable, but evolving,” Humphrey writes. “Gin has always interested a younger generation of drinker, as well as commitment from the older crowd, while maintaining a reputation among the middle aged. It is unique that way.” That checks out from my experience of tastings and the fact that it’s my mother-in-law’s tipple of choice as well. (Birthday gift from my Bookshop wish list) [134 pages] ![]()

The Serviceberry: An Economy of Gifts and Abundance by Robin Wall Kimmerer (2024)

Serviceberries (aka saskatoons or juneberries) are Kimmerer’s chosen example of nature’s bounty, freely offered and reliable. When her farmer neighbours invite people to come and pick pails of them for nothing, they’re straying from the prevailing economic reasoning that commodifies food. Instead of focusing on the “transactional,” they’re “banking goodwill, so-called social capital.” Kimmerer would disdain the term “ecosystem services,” arguing that turning nature into a commodity has diminished people’s sense of responsibility and made them feel more justified in taking whatever they want and hoarding it. Capitalism’s reliance on scarcity (sometimes false or forced) is anathema to her; in an Indigenous gift-based economy, there is sufficient for all to share: “You can store meat in your own pantry or in the belly of your brother.” I love that she refers to Little Free Libraries and other community initiatives such as farm stands of free produce, swap shops, and online giveaway forums. I volunteer with our local Repair Café, I curate my neighbourhood Little Free Library, and I’m lucky to live in a community where people are always giving away quality items. These are all win-win situations where unwanted or broken items get a new lease on life. Save landfill space, resources, and money at the same time! Compared to Braiding Sweetgrass, this is thin (but targeted) and sometimes feels overly optimistic about human nature. I was glad I didn’t buy the bite-sized hardback with gift money last year, but I was happy to have a chance to read the book anyway. (New purchase – Kindle 99p deal) [124 pages]

Serviceberries (aka saskatoons or juneberries) are Kimmerer’s chosen example of nature’s bounty, freely offered and reliable. When her farmer neighbours invite people to come and pick pails of them for nothing, they’re straying from the prevailing economic reasoning that commodifies food. Instead of focusing on the “transactional,” they’re “banking goodwill, so-called social capital.” Kimmerer would disdain the term “ecosystem services,” arguing that turning nature into a commodity has diminished people’s sense of responsibility and made them feel more justified in taking whatever they want and hoarding it. Capitalism’s reliance on scarcity (sometimes false or forced) is anathema to her; in an Indigenous gift-based economy, there is sufficient for all to share: “You can store meat in your own pantry or in the belly of your brother.” I love that she refers to Little Free Libraries and other community initiatives such as farm stands of free produce, swap shops, and online giveaway forums. I volunteer with our local Repair Café, I curate my neighbourhood Little Free Library, and I’m lucky to live in a community where people are always giving away quality items. These are all win-win situations where unwanted or broken items get a new lease on life. Save landfill space, resources, and money at the same time! Compared to Braiding Sweetgrass, this is thin (but targeted) and sometimes feels overly optimistic about human nature. I was glad I didn’t buy the bite-sized hardback with gift money last year, but I was happy to have a chance to read the book anyway. (New purchase – Kindle 99p deal) [124 pages] ![]()

The Harvest Gypsies: On the Road to The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck (1936; 1988)

This lucky find is part of the “California Legacy” collection published by Heyday and Santa Clara University. In October 1936, Steinbeck produced a series of seven articles for The San Francisco News about the plight of Dust Bowl-era migrant workers. His star was just starting to rise but he wouldn’t achieve true fame until 1939 with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, which was borne out of his travels as a journalist. Some 150,000 transient workers traveled the length of California looking for temporary employment in the orchards and vegetable fields. Squatters’ camps were places of poor food and hygiene where young children often died of disease or malnutrition. Women in their thirties were worn out by annual childbirth and frequent miscarriage and baby loss. Dignity was hard to maintain without proper toilet facilities. Because workers moved around, they could not establish state residency and so had no access to healthcare or unemployment benefits. This distressing material is captured through dispassionate case studies. Steinbeck gives particular attention to the state’s poor track record for the treatment of foreign workers – Chinese, Japanese and Filipino as well as Mexican. He recounts disproportionate police brutality in response to workers’ attempts to organize. (Has anything really changed?!) In the final article, he offers solutions: the right to unionize, and blocks of subsistence farms on federal land. Charles Wollenberg’s introduction about Steinbeck and his tour guide, camp manager Tom Collins, is illuminating and Dorothea Lange’s photographs are the perfect accompaniment. Now I’m hankering to reread The Grapes of Wrath. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year) [62 pages]

This lucky find is part of the “California Legacy” collection published by Heyday and Santa Clara University. In October 1936, Steinbeck produced a series of seven articles for The San Francisco News about the plight of Dust Bowl-era migrant workers. His star was just starting to rise but he wouldn’t achieve true fame until 1939 with the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath, which was borne out of his travels as a journalist. Some 150,000 transient workers traveled the length of California looking for temporary employment in the orchards and vegetable fields. Squatters’ camps were places of poor food and hygiene where young children often died of disease or malnutrition. Women in their thirties were worn out by annual childbirth and frequent miscarriage and baby loss. Dignity was hard to maintain without proper toilet facilities. Because workers moved around, they could not establish state residency and so had no access to healthcare or unemployment benefits. This distressing material is captured through dispassionate case studies. Steinbeck gives particular attention to the state’s poor track record for the treatment of foreign workers – Chinese, Japanese and Filipino as well as Mexican. He recounts disproportionate police brutality in response to workers’ attempts to organize. (Has anything really changed?!) In the final article, he offers solutions: the right to unionize, and blocks of subsistence farms on federal land. Charles Wollenberg’s introduction about Steinbeck and his tour guide, camp manager Tom Collins, is illuminating and Dorothea Lange’s photographs are the perfect accompaniment. Now I’m hankering to reread The Grapes of Wrath. (Secondhand – Gifted by a friend as part of a trip to Community Furniture Project, Newbury last year) [62 pages] ![]()

Check out Kris Drever’s folk song “Harvest Gypsies” (written by Boo Hewerdine) here.

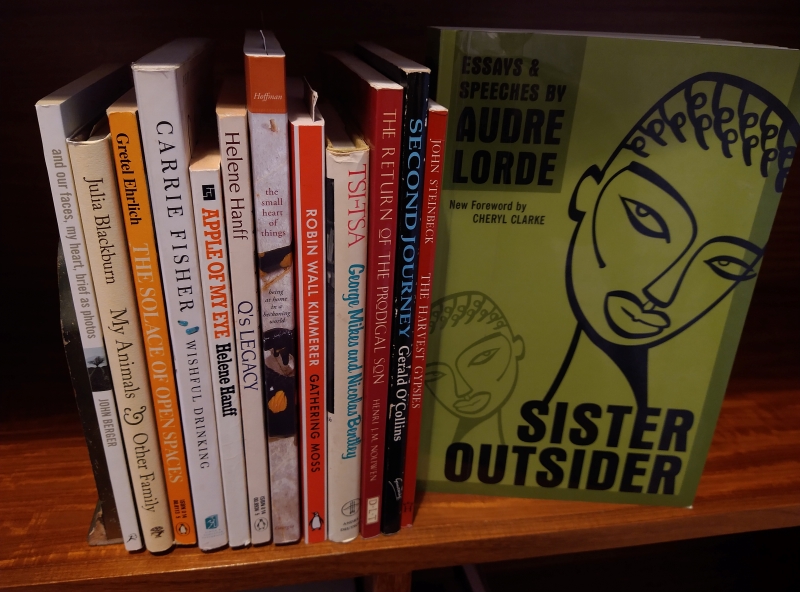

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde (#NovNov25 Buddy Read, #NonfictionNovember)

This year we set two buddy reads for Novellas in November: one contemporary work of fiction (Seascraper) and one classic work of short nonfiction. Do let us know if you’ve been reading them and what you think!

Sister Outsider is a 1984 collection of Audre Lorde’s essays and speeches. Many of these short pieces appeared in Black or radical feminist magazines or scholarly journals, while a few give the text of her conference presentations. Lorde must have been one of the first writers to spotlight intersectionality: she ponders the combined effect of her Black lesbian identity on how she is perceived and what power she has in society.

The title’s paradox draws attention to the push and pull of solidarity and ostracism. She calls white feminists out for not considering what women of colour endure (or for making her a token Black speaker); she decries misogyny in the Black community; and she and her white lover, Frances, seem to attract homophobia from all quarters. Especially while trying to raise her Black teenage son to avoid toxic masculinity, the author comes to realise the importance of “learning to address each other’s difference with respect.”

This is a point she returns to again and again, and it’s as important now as it was when she was writing in the 1970s. So many forms of hatred and discrimination come down to difference being seen as a threat – “I disagree with you, so I must destroy you” is how she caricatures that perspective.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

Even if you’ve never read a word that Lorde wrote, you probably know the phrase “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – this talk title refers to having to circumvent the racist patriarchy to truly fight oppression. “Revolution is not a one-time event,” she writes in another essay. “It is becoming always vigilant for the smallest opportunity to make a genuine change in established, outgrown responses”.

My two favourite pieces here also feel like they have entered into the zeitgeist. “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” deems poetry a “necessity for our existence … the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought.” And “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” is a thrilling redefinition of a holistic sensuality that means living at full tilt and tapping into creativity. “The sharing of joy, whether physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual, forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared”.

In some ways this is not an ideal way to be introduced to Lorde’s work, because many of the essays repeat the same themes and reasoning. I made my way through the book very slowly, one piece every day or few days. The speeches would almost certainly be more effective if heard aloud, as intended – and more provocative, too, as they must have undermined other speakers’ assumptions. I was also a bit taken aback by the opening and closing pieces being travelogues: “Notes from a Trip to Russia” is based on journal entries from 1976, while “Grenada Revisited: An Interim Report” about a 1983 trip to her mother’s birthplace. I saw more point to the latter, while the former felt somewhat out of place.

Nonetheless, Lorde’s thinking is essential and ahead of its time. I’d only previously read her short work The Cancer Journals. For years my book club has been toying with reading Zami, her memoir starting with growing up in 1930s Harlem, so I’ll hope to move that up the agenda for next year. Have you read any of her other books that you can recommend?(University library) [190 pages]

Other reviews of Sister Outsider:

Cathy (746 Books)

Marcie (Buried in Print) is making her way through the book one essay at a time. Here’s her latest post.

Three on a Theme of Sylvia Plath (The Slicks by Maggie Nelson for #NonfictionNovember & #NovNov25; The Bell Jar and Ariel)

A review copy of Maggie Nelson’s brand-new biographical essay on Sylvia Plath (and Taylor Swift) was the excuse I needed to finally finish a long-neglected paperback of The Bell Jar and also get a taste of Plath’s poetry through the posthumous collection Ariel, which is celebrating its 60th anniversary. These are the sorts of works it’s hard to believe ever didn’t exist; they feel so fully formed and part of the zeitgeist. It also boggles the mind how much Plath accomplished before her death by suicide at age 30. What I previously knew of her life mostly came from hearsay and was reinforced by Euphoria by Elin Cullhed. For the mixture of nonfiction, fiction and poetry represented below, I’m counting this towards Nonfiction November’s Book Pairings week.

The Slicks: On Sylvia Plath and Taylor Swift by Maggie Nelson (2025)

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Can young women embrace fame amidst the other cultural expectations of them? Nelson attempts to answer this question by comparing two figures who turn(ed) life into art. The link between them was strengthened by Swift titling her 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department. “Plath … serves as a metonym – as does Swift – for a woman who makes art about a broken heart,” Nelson writes. “When women make the personal public, the charge of whorishness always lurks nearby.” What women are allowed to say and do has always, it seems, attracted public commentary, and “anyone who puts their work into the world, at any level, must learn to navigate between self-protectiveness and risk, becoming harder and staying soft.”

Nelson acknowledges a major tonal difference between Plath and Swift, however. Plath longed for fame but didn’t get the chance to enjoy it; she’s the patron saint of sad-girl poetry and makes frequent reference to death, whereas Swift spotlights joy and female empowerment. It’s a shame this was out of date before it went to print; my advanced copy, at least, isn’t able to comment on Swift’s engagement and the baby rumour mill sure to follow. It would be illuminating to have an afterword in which Nelson discusses the effect of spouses’ competing fame and speculates on how motherhood might change Swift’s art.

Full confession: I’ve only ever knowingly heard one Taylor Swift song, “Anti-Hero,” on the radio in the States. (My assessment was: wordy, angsty, reasonably catchy.) Undoubtedly, I would have gotten more out of this essay were I equally familiar with the two subjects. Nonetheless, it’s fluid and well argued, and I was engaged throughout. If you’re a Swiftie as well as a literary type, you need to read this.

[66 pages]

With thanks to Vintage (Penguin) for the advanced e-copy for review.

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

Given my love of mental hospital accounts and women’s autofiction, it’s a wonder I’d not read this before my forties. It was first published under the pseudonym “Victoria Lucas” because Plath thought it immature, “an autobiographical apprentice work which I had to write in order to free myself from the past.” Esther Greenwood is the stand-in for Plath: a talented college student who, after working in New York City during the remarkable summer of 1953, plunges into mental ill health. Chapter 13 is amazing and awful at the same time as Esther attempts suicide thrice in one day, toying with a silk bathrobe cord and ocean waves before taking 50 pills and walling herself into a corner of the cellar. She bounces between various institutional settings, undergoing electroshock therapy – the first time it’s horrible, but later, under a kind female doctor, it’s more like it’s ‘supposed’ to be: a calming reset.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

The 19-year-old is obsessed with the notion of purity. She has a couple of boyfriends but decides to look for someone else to take her virginity. Beforehand, the asylum doctor prescribes her a fitting for a diaphragm. A defiant claim to the right to contraception despite being unmarried is a way of resisting the bell jar – the rarefied prison – of motherhood. Still, Esther feels guilty about prioritizing her work over what seems like feminine duty: “Why was I so maternal and apart? Why couldn’t I dream of devoting myself to baby after fat puling baby? … I was my own woman.” Plath never reconciled parenthood with poetry. Whether that’s the fault of Ted Hughes, or the times they lived in, who can say. For her and for Esther, the hospital is a prison as well – but not so hermetic as the turmoil of her own mind. How ironic to read “I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart. I am, I am, I am” knowing that this was published just a few weeks before this literary genius ceased to be.

Apart from an unfortunate portrayal of a “negro” worker at the hospital, this was an enduringly relevant and absorbing read, a classic to sit alongside Emily Holmes Coleman’s The Shutter of Snow and Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water.

(Secondhand – it’s been in my collection so long I can’t remember where it’s from, but I’d guess a Bowie Library book sale or Wonder Book & Video / Public library – I was struggling with the small type so switched to a recent paperback and found it more readable)

Ariel by Sylvia Plath (1965)

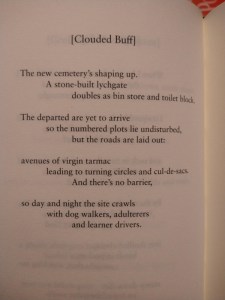

Impossible not to read this looking for clues of her death to come:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

(from “Lady Lazarus”)

Eternity bores me,

I never wanted it.

(from “Years”)

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment

(from “Edge”)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

I feel incapable of saying anything fresh about this collection, which takes no prisoners. The images and vocabulary are razor-sharp. First and last lines or stanzas are particularly memorable. (“Morning Song” starts “Love set you going like a fat gold watch”; “Lady Lazarus” ends “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.”) Words and phrases repeat and gather power as they go. “The Applicant” mocks the obligations of a wife: “A living doll … / It can sew, it can cook. It can talk, talk, talk. … // … My boy, it’s your last resort. / Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.” I don’t know a lot about Plath’s family life, only that her father was a Polish immigrant and died after a long illness when she was eight, but there must have been some daddy issues there – after all, “Daddy” includes the barbs “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two— / The vampire who said he was you / And drank my blood for a year, / Seven years, if you want to know.” It ends, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Several later poems in a row, including “Stings,” incorporate bee-related imagery, and Plath’s father was an international bee expert. I can see myself reading this again and again in future, and finding her other collections, too – all but one of them posthumous. (Secondhand – RSPCA charity shop, Newbury)

#NovNov25 and Other November Reading Plans

Not much more than two weeks now before Novellas in November (#NovNov25) begins! Cathy and I are getting geared up and making plans for what we’re going to read. I have a handful of novellas out from the library, but mostly I gathered potential reads from my own shelves. I’m hoping to coincide with several of November’s other challenges, too.

Although we’re not using the below as themes this year, I’ve grouped my options into categories:

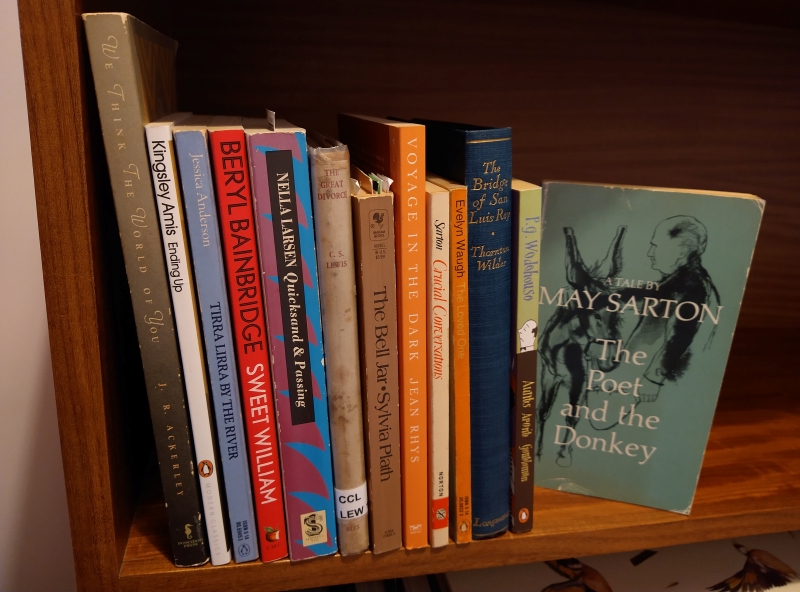

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Just Quicksand to read from the Larsen volume; the Wilder would be a reread.

Contemporary Novellas

(Just Blow Your House Down; and the last two of the three novellas in the Hynes.)

Also, on my e-readers: Sea, Poison by Caren Beilin, Likeness by Samsun Knight, Eradication: A Fable by Jonathan Miles (a 2026 release, to review early for Shelf Awareness)

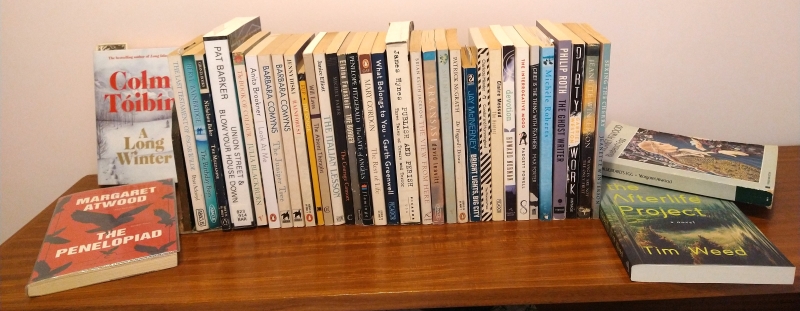

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

*Margaret Atwood Reading Month is hosted by Marcie of Buried in Print. I’ve just read The Penelopiad for book club, so I’ll start off with a review of that. I might also reread Bluebeard’s Egg, and I’ll be eagerly awaiting her memoir from the library.

[*Science Fiction Month: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, Archive of Unknown Universes by Ruben Reyes Jr., and The Afterlife Project (all catch-up review books) are options, plus I recently started reading The Martian by Andy Weir.]

Short Nonfiction

Including our buddy read, Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde. (A shame about that cover!)

Also, on my e-readers: The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer, No Straight Road Takes You There by Rebecca Solnit, Because We Must by Tracy Youngblom. And, even though it doesn’t come out until February, I started reading The Irish Goodbye: Micro-Memoirs by Beth Ann Fennelly via Edelweiss.

For Nonfiction November, I also have plenty of longer nonfiction on the go, a mixture of review books to catch up on and books from the library:

I also have one nonfiction November release, Joyride by Susan Orlean, to review.

Novellas in Translation

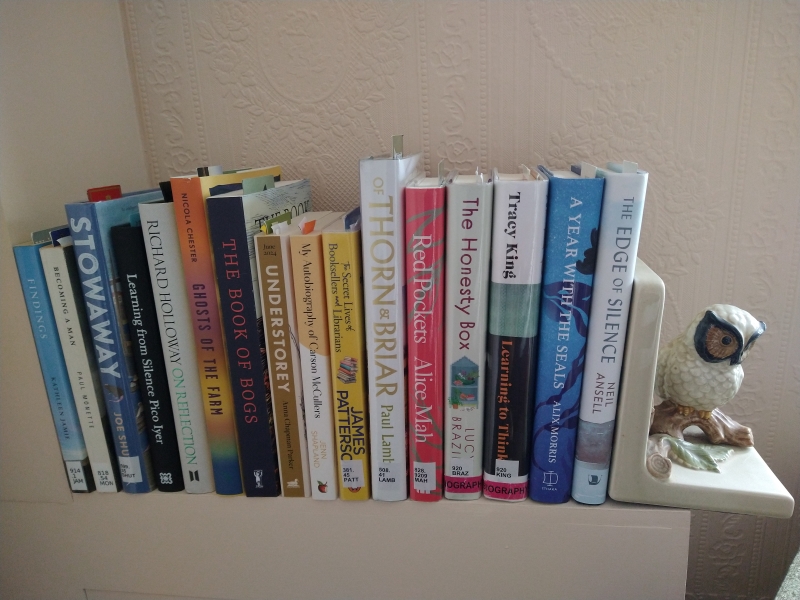

At left are all the novella-length options, with four German books on top.

The Chevillard and Modiano are review copies to catch up on.

Also on the stack, from the library: Super-Frog Saves Tokyo by Haruki Murakami

On my e-readers: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Man by the Sea by Domenico Starnone, Our Precious Wars by Perrine Tripier

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

*German Literature Month: Our recent trip to Berlin and Lübeck whetted my appetite to read more German/German-language fiction. I’ll try to coincide with the Thomas Mann week as I was already planning to reread Death in Venice. I have some longer German books on the right-hand side as well. I started Kairos but found it hard going so might switch to audiobook. I also have Demian by Hermann Hesse on my Nook, downloaded from Project Gutenberg.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles?

The link-up is now open for you to share your planning post!

Any novellas lined up to read next month?

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Autistic Husbands & The Ocean

Liz is the host for this week’s Nonfiction November prompt. The idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with these two based on my recent reading:

An Autistic Husband

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion (also The Rosie Project and The Rosie Result)

&

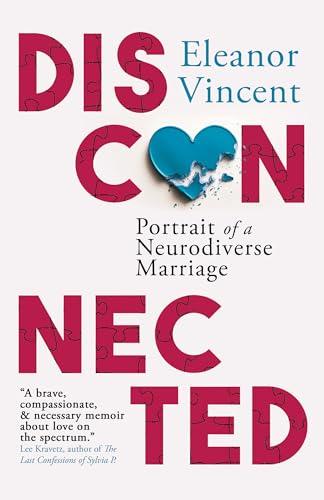

Disconnected: Portrait of a Neurodiverse Marriage by Eleanor Vincent

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

Graeme Simsion’s Don Tillman trilogy tells the odd-couple story of an autistic professor and how he falls in love with and marries a wholly unsuitable neurotypical woman. He turns this situation into romantic comedy. For Eleanor Vincent, it wasn’t so funny. She met her third husband, computer scientist Lars (a pseudonym), through Zydeco dancing when she was in her sixties. Though aware that he could be unemotional and act strangely, she found him chivalrous and sweet. They dated for a time but he hurt and confused her by asking for his apartment keys back. After a five-year period she calls their “Interregnum,” the two got back together and married. Despite their years of friendship, she was completely unprepared for what living with him would be like. “At the age of seventy-one, I had married a stranger,” she writes.

It didn’t help that Covid hit partway through their four-year marriage, nor that they each received a cancer diagnosis (cervical vs. prostate). But the problems were more with their everyday differences in responses and processing. During their courtship, she ignored some bizarre things he did around her family: he bit her nine-year-old granddaughter as a warning of what would happen if she kept antagonizing their cat, and he put a gift bag over his head while they were at the dinner table with her siblings. These are a couple of the most egregious instances, but there are examples throughout of how Lars did things she didn’t understand. Through support groups and marriage counselling, she realized how well Lars had masked his autism when they were dating – and that he wasn’t willing to do the work required to make their marriage succeed. The book ends with them estranged but a divorce imminent.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

If this were purely carping about a husband’s weirdness, it might have been tedious or depressing. But Vincent doesn’t blame Lars, and she incorporates so much else in this short memoir, including a number of topics that are of particular interest to me. There’s her PTSD from a traumatic upbringing, her parents’ identity as closeted gay people, the complications around her father’s death, the tragedy of her older daughter’s death, as well as the more everyday matters of being a working single parent, finding an affordable property in California’s Bay Area, and blending households.

Vincent crafts engaging scenes with solid recreated dialogue, and I especially liked the few meta chapters revealing “What I Left Out” – a memoir is always a shaped narrative, while life is messy; this shows both. She is also honest about her own failings and occasional bad behavior. I probably could have done with a little less detail on their sex life, however.

This had more relevance to me than expected. While my sister and I were clearing our mother’s belongings from the home she shared with her second husband for the 16 months between their wedding and her death, our stepsisters mentioned to us that they suspected their father was autistic. It was, as my sister said, a “lightbulb” moment, explaining so much about our respective parents’ relationship, and our interactions with him as well. My stepfather (who died just 10 months after my mother) was a dear man, but also maddening at times. A retired math professor, he was logical and flat of affect. Sometimes his humor was off-kilter and he made snap, unsentimental decisions that we couldn’t fathom. Had they gotten longer together, no doubt many of the issues Vincent experienced would have arisen. (Read via BookSirens)

[173 pages]

The Ocean

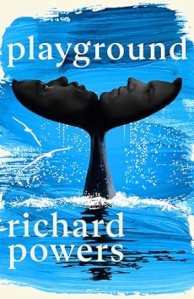

Playground by Richard Powers

&

Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love by Lida Maxwell

The Blue Machine by Helen Czerski

Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

While I was less than enraptured with its artificial intelligence theme and narrative trickery, I loved the content about the splendour of the ocean in Richard Powers’s Booker Prize-longlisted Playground. Most of this comes via Evelyne Beaulieu, a charismatic French Canadian marine biologist (based in part on Sylvia Earle) who is on the first all-female submarine mission and is still diving in the South Pacific in her nineties. Powers explicitly references Rachel Carson’s The Sea Around Us. Between that and the revelation of Evelyne as a late-bloomer lesbian, I was reminded of Rachel Carson and the Power of Queer Love, a forthcoming novella-length academic study by Lida Maxwell that I have assessed for Foreword Reviews. Maxwell’s central argument is that Carson’s romantic love for a married woman, Dorothy Freeman, served as an awakening to wonder and connection and spurred her to write her greatest works.

After reading Playground, I decided to place a library hold on Blue Machine by Helen Czerski (winner of the Wainwright Writing on Conservation Prize this year), which Powers acknowledges as an inspiration that helped him to think bigger. I have also pulled my copy of Under the Sea Wind by Rachel Carson off the shelf as it’s high time I read more by her.

Previous book pairings posts: 2018 (Alzheimer’s, female friendship, drug addiction, Greenland and fine wine!) and 2023 (Hardy’s Wives, rituals and romcoms).

Short Nonfiction Series for Novellas in November + Nonfiction November

Most Novellas in November participants focus on fiction, which is understandable and totally fine; I also like to incorporate works of short nonfiction during the month, which is a great opportunity to combine challenges with Nonfiction November.

Building on this list I wrote in 2021 (all the recommendations stand, but I’d update it by adding Weatherglass Books to the list of UK publishers), here are some nonfiction series that publish brief, intriguing works:

404 Ink’s Inklings series bears the tagline “big ideas to carry in your pocket.”

I have reviewed Happy Death Club.

I have reviewed Happy Death Club.

Biteback Publishing’s Provocations series “is a groundbreaking new series of short polemics composed by some of the most intriguing voices in contemporary culture.”

- I have reviewed Last Rights. I spied a pair of books by John Sutherland on youth and ageing at my library.

Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series “is a series of concise, collectable, beautifully designed books about the hidden lives of ordinary things.”

- I have reviewed Doctor, Dust, Grave, Pregnancy Test, and Recipe.

Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 is “a series of short books about popular music.”

- I have reviewed Jesus Freak.

Bristol University Press’s What Is It For series is edited by George Miller, creator of the OUP Very Short Introductions (see below). Miller believes “short, affordable books can, and should, be intelligent and thought-provoking”; he hopes these will “be an agent for positive change,” addressing “tough questions about purpose and fitness for purpose: what has to change for the future to be better?”

A number of Fitzcarraldo Editions’ Essays are significantly under 200 pages.

I have reviewed Intervals, A Very Easy Death, Happening, I Remain in Darkness, A Woman’s Story, and Alphabetical Diaries (plus others that are longer).

I have reviewed Intervals, A Very Easy Death, Happening, I Remain in Darkness, A Woman’s Story, and Alphabetical Diaries (plus others that are longer).

[Edited:] Thanks so much to Liz for letting me know about Jacaranda Books’ A Quick Ting On series, “the first ever non-fiction book series dedicated to Black British culture,” with books on plantains, Grime music, Black hair, and more.

[Edited:] There are three books so far in the Leaping Hare Press Find Your Path self-help series. I have just downloaded Find Your Path through Imposter Syndrome from Edelweiss.

Little Toller Books publishes mostly short nature and travel monographs and reprints.

- I have reviewed Deer Island, Aurochs and Auks, Orison for a Curlew, Herbaceous, The Ash Tree, and Snow.

From the Little Toller website

[Edited:] Thanks so much to Annabel for making me aware of Melville House’s The FUTURES series, which gives “imaginative future visions on a wide range of subjects, written by experts, academics, journalists and leading pop-culture figures.”

MIT Press’s Essential Knowledge series “offers accessible, concise, beautifully produced books on topics of current interest.” I spotted the Plastics book at my library.

Oxford University Press’s Very Short Introductions now cover a whopping 867 subjects!

- I had a couple of them assigned in my college days, including Judaism.

Penguin’s 100-book Great Ideas series reprints essays that introduce readers to “history’s most important and game-changing theories, philosophies and discoveries in accessible, concise editions.”

A number of Profile’s health-themed Wellcome Collection Books are well under 200 pages.

- I have reviewed Recovery, Free for All, Chasing the Sun, An Extra Pair of Hands, and After the Storm (plus others that are longer).

Saraband’s In the Moment series contains “portable, accessible books … exploring the role of both mind and body in movement, purpose, and reflection, finding ways of being fully present in our activities and environment.”

- I’m interested in Writing Landscape by Linda Cracknell and On Community by Casey Plett.

Most of the original School of Life books are around 150 pages long. Their newer Essential Ideas series of three titles also promises “pocket books.”

Most of the original School of Life books are around 150 pages long. Their newer Essential Ideas series of three titles also promises “pocket books.”

- I have reviewed How to Develop Emotional Health, How to Age, How to Be Alone, and How to Think about Exercise.

Why not see if your local library has any selections from one or more of these series? #LoveYourLibrary

If you’re a reluctant nonfiction reader, choosing a short book could be a great way to engage with a topic that interests you – without a major time commitment. #NonfictionNovember

Keep in touch via X (@bookishbeck / @cathy746books) and Instagram (@bookishbeck / @cathy_746books). Add any related posts to the link-up. Don’t forget the hashtag #NovNov24.

Any suitable short nonfiction on your shelves?

Nonfiction November Book Pairings: Hardy’s Wives, Rituals, and Romcoms

Liz is hosting this week of Nonfiction November. For this prompt, the idea is to choose a nonfiction book and pair it with a fiction title with which it has something in common.

I came up with three based on my recent reading:

Thomas Hardy’s Wives

On my pile for Novellas in November was a tiny book I’ve owned for nearly two decades but not read until now. It contains some of the backstory for an excellent historical novel I reviewed earlier in the year.

Some Recollections by Emma Hardy

&

The Chosen by Elizabeth Lowry

The manuscript of Some Recollections is one of the documents Thomas Hardy found among his first wife’s things after her death in 1912. It is a brief (15,000-word) memoir of her early life from childhood up to her marriage – “My life’s romance now began.” Her middle-class family lived in Plymouth and moved to Cornwall when finances were tight. (Like the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice, you look at the house they lived in, and read about the servants they still employed, and think, “impoverished,” seriously?!) “Though trifling as they may seem to others all these memories are dear to me,” she writes. It’s true that most of these details seem inconsequential, of folk historical value but not particularly illuminating about the individual.

An exception is her account of her dealings with fortune tellers, who often went out of their way to give her good – and accurate – predictions, such as that she would marry a writer. It’s interesting to set this occult belief against the traditional Christian faith she espouses in her concluding paragraph, in which she insists an “Unseen Power of great benevolence directs my ways.” The other point of interest is her description of her first meeting with Hardy, who was sent to St. Juliot, where she was living with her parson brother-in-law and sister, as an architect’s assistant to begin repairs on the church. “I thought him much older than he was,” she wrote. As editor Robert Gittings notes, Hardy made corrections to the manuscript and in some places also changed the sense. Here Hardy gave proof of an old man’s continued vanity by adding “he being tired” after that line … but then partially rubbing it out. (Secondhand, Books for Amnesty, Reading, 2004) [64 pages]

The Chosen contrasts Emma’s idyllic mini memoir with her bitterly honest journals – Hardy read but then burned these, so Lowry had to recreate their entries based on letters and tone. But Some Recollections went on to influence his own autobiography, and to be published in a stand-alone volume by Oxford University Press. Gittings introduces the manuscript (complete with Emma’s misspellings and missing punctuation) and appends a selection of Hardy’s late poems based on his first marriage – this verse, too, is central to The Chosen.

Another recent nonfiction release on this subject matter that I learned about from a Shiny New Books review is Woman Much Missed: Thomas Hardy, Emma Hardy and Poetry by Mark Ford. I’d also like to read the forthcoming Hardy Women: Mother, Sisters, Wives, Muses by Paula Byrne (1 February 2024, William Collins).

Rituals

The Ritual Effect by Michael Norton

&

The Rituals by Rebecca Roberts

Last month I reviewed this lovely Welsh novel about a woman who is an independent celebrant, helping people celebrate landmark events in their lives or cope with devastating losses by commemorating them through secular rituals.

Coming out in April 2024, The Ritual Effect is a Harvard Business School behavioral scientist’s wide-ranging study of how rituals differ from habits in that they are emotionally charged and lift everyday life into something special. Some of his topics are rites of passage in different cultures; musicians’ and sportspeople’s pre-performance routines; and the rituals we develop around food and drink, especially at the holidays. I’m just over halfway through this for an early Shelf Awareness review and I have been finding it fascinating.

Romantic Comedy

(As also featured in my August Six Degrees post)

What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding by Kristin Newman

&

Romantic Comedy by Curtis Sittenfeld

Romantic Comedy is probably still the most fun reading experience I’ve had this year. Sittenfeld’s protagonist, Sally Milz, writes TV comedy, as does Kristin Newman (That ’70s Show, How I Met Your Mother, etc.). What I Was Doing While You Were Breeding is a lighthearted record of her sexual conquests in Amsterdam, Paris, Russia, Argentina, etc. (Newman even has a passage that reminds me of Sally’s “Danny Horst Rule”: “I looked like a thirty-year-old writer. Not like a twenty-year-old model or actress or epically legged songstress, which is a category into which an alarmingly high percentage of Angelenas fall. And, because the city is so lousy with these leggy aliens, regular- to below-average-looking guys with reasonable employment levels can actually get one, another maddening aspect of being a woman in this city.”) Unfortunately, it got repetitive and raunchy. It was one of my 20 Books of Summer but I DNFed it halfway.

I died and went

I died and went I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this.

I’ve read the first two chapters of a long-neglected review copy of All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell (2022), in which she shadows various individuals who work in the death industry, starting with a funeral director and the head of anatomy services for the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In Victorian times, corpses were stolen for medical students to practice on. These days, more people want to donate their bodies to science than can usually be accommodated. The Mayo Clinic receives upwards of 200 cadavers a year and these are the basis for many practical lessons as trainees prepare to perform surgery on the living. Campbell’s prose is journalistic, detailed and matter-of-fact, but I’m struggling with the very small type in my paperback. Upcoming chapters will consider a death mask sculptor, a trauma cleaner, a gravedigger, and more. If you’ve enjoyed Caitlin Doughty’s books, try this. I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing.

I’m halfway through Red Pockets: An Offering by Alice Mah (2025) from the library. I borrowed it because it was on the Wainwright Prize for Conservation Writing shortlist. During the Qingming Festival, the Chinese return to their hometowns to honour their ancestors. By sweeping their tombs and making offerings, they prevent the dead from coming back as hungry ghosts. When Mah, who grew up in Canada and now lives in Scotland, returns to South China with a cousin in 2017, she finds little trace of her ancestors but plenty of pollution and ecological degradation. Their grandfather wrote a memoir about his early life and immigration to Canada. In the present day, the cousins struggle to understand cultural norms such as gifting red envelopes of money to all locals. This is easy reading but slightly dull; it feels like Mah included every detail from her trips simply because she had the material, whereas memoirs need to be more selective. But I’m reminded of the works of Jessica J. Lee, which is no bad thing. Perry traces the physical changes in David as he moved with alarming alacrity from normal, if slowed, daily life to complete dependency to death’s door. At the same time, she is aware that this is only her own perspective on events, so she records her responses and emotional state and, to a lesser extent, her husband’s. Her quiver of allusions is perfectly chosen and she lands on just the right tone: direct but tender. Because of her and David’s shared upbringing, the points of reference are often religious, but not obtrusive. My only wish is to have gotten more of a sense of David alive. There’s a brief section on his life at the start, mirrored by a short “Afterlife” chapter at the end telling what succeeded his death. But the focus is very much on the short period of his illness and the days of his dying. During this time, he appears confused and powerless. He barely says anything beyond “I’m in a bit of a muddle,” to refer to anything from incontinence to an inability to eat. At first I thought this was infantilizing him. But I came to see it as a way of reflecting how death strips everything away.

Perry traces the physical changes in David as he moved with alarming alacrity from normal, if slowed, daily life to complete dependency to death’s door. At the same time, she is aware that this is only her own perspective on events, so she records her responses and emotional state and, to a lesser extent, her husband’s. Her quiver of allusions is perfectly chosen and she lands on just the right tone: direct but tender. Because of her and David’s shared upbringing, the points of reference are often religious, but not obtrusive. My only wish is to have gotten more of a sense of David alive. There’s a brief section on his life at the start, mirrored by a short “Afterlife” chapter at the end telling what succeeded his death. But the focus is very much on the short period of his illness and the days of his dying. During this time, he appears confused and powerless. He barely says anything beyond “I’m in a bit of a muddle,” to refer to anything from incontinence to an inability to eat. At first I thought this was infantilizing him. But I came to see it as a way of reflecting how death strips everything away. Barcode by Jordan Frith: The barcode was patented in 1952 but didn’t come into daily use until 1974. It was developed for use by supermarkets – the Universal Product Code or UPC. (These days a charity shop is the only place you might have a shopping experience that doesn’t rely on barcodes.) A grocery industry committee chose between seven designs, two of which were round. IBM’s design won and became the barcode as we know it. “Barcodes are a bit of a paradox,” Frith, a communications professor with previous books on RFID and smartphones to his name, writes. “They are ignored yet iconic. They are a prime example of the learned invisibility of infrastructure yet also a prominent symbol of cultural critique in everything from popular science fiction to tattoos.” In 1992, President Bush was considered to be out of touch when he expressed amazement at barcode scanning technology. I was most engaged with the chapter on the Bible – Evangelicals, famously, panicked that the Mark of the Beast heralded by the book of Revelation would be an obligatory barcode tattooed on every individual. While I’m not interested enough in technology to have read the whole thing, which does skew dry, I found interesting tidbits by skimming. (Public library) [152 pages]

Barcode by Jordan Frith: The barcode was patented in 1952 but didn’t come into daily use until 1974. It was developed for use by supermarkets – the Universal Product Code or UPC. (These days a charity shop is the only place you might have a shopping experience that doesn’t rely on barcodes.) A grocery industry committee chose between seven designs, two of which were round. IBM’s design won and became the barcode as we know it. “Barcodes are a bit of a paradox,” Frith, a communications professor with previous books on RFID and smartphones to his name, writes. “They are ignored yet iconic. They are a prime example of the learned invisibility of infrastructure yet also a prominent symbol of cultural critique in everything from popular science fiction to tattoos.” In 1992, President Bush was considered to be out of touch when he expressed amazement at barcode scanning technology. I was most engaged with the chapter on the Bible – Evangelicals, famously, panicked that the Mark of the Beast heralded by the book of Revelation would be an obligatory barcode tattooed on every individual. While I’m not interested enough in technology to have read the whole thing, which does skew dry, I found interesting tidbits by skimming. (Public library) [152 pages]  Island by Julian Hanna: The most autobiographical, loosest and least formulaic of these three, and perhaps my favourite in the series to date. Hanna grew up on Vancouver Island and has lived on Madeira; his genealogy stretches back to another island nation, Ireland. Through disparate travels he comments on islands that have long attracted expats: Hawaii, Ibiza, and Hong Kong. From sweltering Crete to the polar night, from family legend to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the topics are as various as the settings. Although Hanna is a humanities lecturer, he even gets involved in designing a gravity battery for Eday in the Orkneys (fully powered by renewables), having won funding through a sustainable energy prize, and is part of a team that builds one in situ there in three days. I admired the honest exploration of the positives and negatives of islands. An island can promise paradise, a time out of time, “a refuge for eccentrics.” Equally, it can be a site of isolation, of “domination and exploitation of fellow humans and of nature.” We may think that with the Internet the world has gotten smaller, but islands are still bastions of distinct culture. In an era of climate crisis, though, some will literally cease to exist. Written primarily during the Covid years, the book contrasts the often personal realities of death, grief and loneliness with idyllic desert-island visions. Whimsically, Hanna presents each chapter as a message in a bottle. What a different book this would have been if written by, say, a geographer. (Read via Edelweiss) [180 pages]

Island by Julian Hanna: The most autobiographical, loosest and least formulaic of these three, and perhaps my favourite in the series to date. Hanna grew up on Vancouver Island and has lived on Madeira; his genealogy stretches back to another island nation, Ireland. Through disparate travels he comments on islands that have long attracted expats: Hawaii, Ibiza, and Hong Kong. From sweltering Crete to the polar night, from family legend to Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, the topics are as various as the settings. Although Hanna is a humanities lecturer, he even gets involved in designing a gravity battery for Eday in the Orkneys (fully powered by renewables), having won funding through a sustainable energy prize, and is part of a team that builds one in situ there in three days. I admired the honest exploration of the positives and negatives of islands. An island can promise paradise, a time out of time, “a refuge for eccentrics.” Equally, it can be a site of isolation, of “domination and exploitation of fellow humans and of nature.” We may think that with the Internet the world has gotten smaller, but islands are still bastions of distinct culture. In an era of climate crisis, though, some will literally cease to exist. Written primarily during the Covid years, the book contrasts the often personal realities of death, grief and loneliness with idyllic desert-island visions. Whimsically, Hanna presents each chapter as a message in a bottle. What a different book this would have been if written by, say, a geographer. (Read via Edelweiss) [180 pages]  X-Ray by Nicole Lobdell: X-ray technology has been with us since 1895, when it was developed by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen. He received the first Nobel Prize in physics but never made any money off of his discovery and died in penury of a cancer that likely resulted from his work. From the start, X-rays provoked concerns about voyeurism. People were right to be wary of X-rays in those early days, but radiation was more of a danger than the invasion of privacy. Lobdell, an English professor, tends to draw slightly simplistic metaphorical messages about the secrets of the body. But X-rays make so many fascinating cultural appearances that I could forgive the occasional lack of subtlety. There’s an in-depth discussion of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, and Superman was only one of the comic-book heroes to boast X-ray vision. The technology has been used to measure feet for shoes, reveal the hidden history of paintings, and keep air travellers safe. I went in for a hospital X-ray of my foot not long after reading this. It was such a quick and simple process, as you’ll find at the dentist’s office as well, and safe enough that my radiographer was pregnant. (Read via Edelweiss) [152 pages]

X-Ray by Nicole Lobdell: X-ray technology has been with us since 1895, when it was developed by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen. He received the first Nobel Prize in physics but never made any money off of his discovery and died in penury of a cancer that likely resulted from his work. From the start, X-rays provoked concerns about voyeurism. People were right to be wary of X-rays in those early days, but radiation was more of a danger than the invasion of privacy. Lobdell, an English professor, tends to draw slightly simplistic metaphorical messages about the secrets of the body. But X-rays make so many fascinating cultural appearances that I could forgive the occasional lack of subtlety. There’s an in-depth discussion of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man, and Superman was only one of the comic-book heroes to boast X-ray vision. The technology has been used to measure feet for shoes, reveal the hidden history of paintings, and keep air travellers safe. I went in for a hospital X-ray of my foot not long after reading this. It was such a quick and simple process, as you’ll find at the dentist’s office as well, and safe enough that my radiographer was pregnant. (Read via Edelweiss) [152 pages]

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning  Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s  Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages] This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino. Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages] After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]