Novellas in November, Week 1: My Year in Novellas (#NovNov23)

Novellas in November begins today! Cathy (746 Books) and I are delighted to be celebrating the art of the short book with you once again. Remember to let us know about your posts here, via the Inlinkz service or through a comment. How impressive is it that before November even started we were already up to 20 blog and social media posts?! I have a feeling this will be a record-breaking year for participation.

I’m kicking off our first weekly prompt:

Week 1 (starts Wednesday 1 November): My Year in Novellas

- During this partial week, tell us about any novellas you have read since last NovNov.

(See the announcement post for more info about the other weeks’ prompts and buddy reads.)

I relish building rather ludicrous stacks of novellas through the year. When I’m standing in front of a Little Free Library, browsing in secondhand bookstores and charity shops, or perusing the shelves at the public library where I volunteer, I’m always thinking about what I could add to my piles for November.

But I do read novella-length books at other times of year, too. Forty-six of them so far this year, according to my Goodreads shelves. That seems impossible, but I guess it reflects the fact that I often choose to review novellas for BookBrowse, Foreword and Shelf Awareness. I’ve read a real mixture, but predominantly literature in translation and autobiographical works. Here are seven highlights:

Fiction

How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman: A strong short story collection with the novella-length “Indigo Run” being a Southern Gothic tale of betrayal and revenge.

Loved and Missed by Susie Boyt: The heart-wrenching story of a woman who adopts her granddaughter due to her daughter’s drug addiction. Its brevity speaks emotional volumes.

Crudo by Olivia Laing: A wry, all too relatable take on recent events and our collective hypocrisy and sense of helplessness. Biography + autofiction + cultural commentary.

Nonfiction

Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop by Alba Donati: Lovely snapshots of a bookseller’s personal and professional life.

La Vie: A Year in Rural France by John Lewis-Stempel: A ‘peasant farmer’ chronicles a year in the quest to become self-sufficient. His best book in an age, ideal for armchair travel.

My Neglected Gods by Joanne Nelson: The poignant microessays locate epiphanies in the everyday.

Eggs in Purgatory by Genanne Walsh: A stunning autobiographical essay about the last few months of her father’s life.

I currently have five novellas underway, and I’ve laid out a pile of potential one-sitting reads for quiet mornings in the weeks to come.

Here’s hoping you all are as excited about short books as I am!

Why not share some recent favourites with us in a post of your own?

Novellas in November 2023 Link-Up

Novellas in November had another great year, with 52 bloggers contributing a total of 175 posts! You can peruse them all at the links below.

Novellas in November Possibility Piles (#NovNov23)

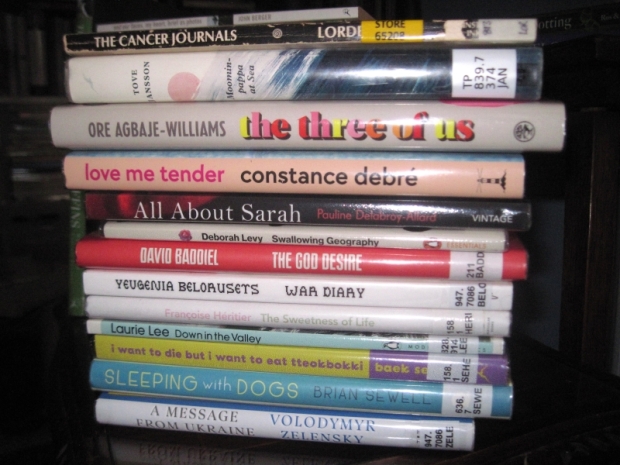

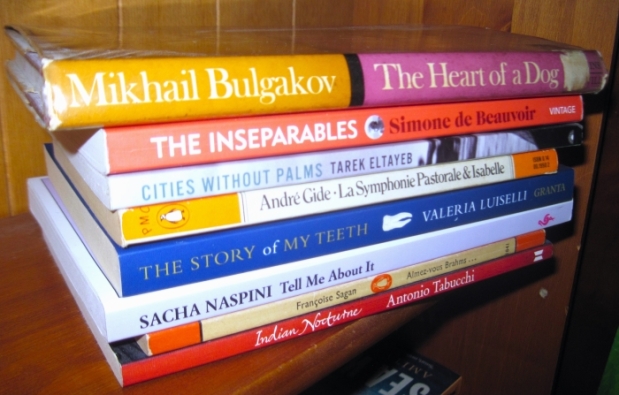

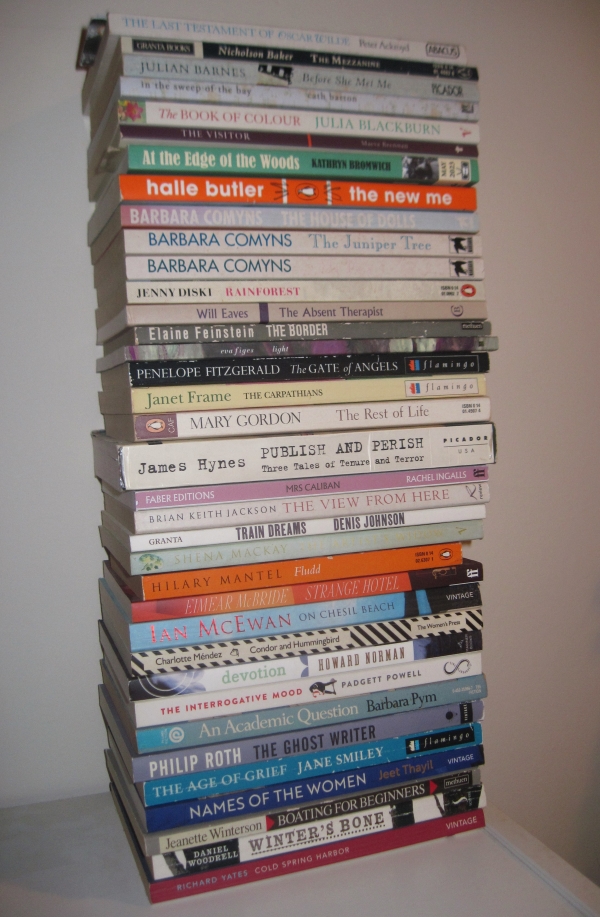

It’s less than a month now until Novellas in November (#NovNov23) begins, so Cathy and I are getting excited and making plans. I gathered up all of my potential reads of under 200 pages for a photo shoot, in rough categories as follows:

Library Haul

Short Classics (pre-1980)

Novellas in Translation

Short Nonfiction

Contemporary Novellas

I’m still awaiting various library holds, including Western Lane by Chetna Maroo, one of our buddy reads for the month; and Ferdinand: The Man with the Kind Heart by Irmgard Keun, which would do double duty for German Literature Month.

I read 29 novellas in November 2021 and 24 in November 2022. I wonder how many I’ll manage this year.

Spy any favourites or a particularly appealing title in my piles? Give me a recommendation for what I should be sure to try to get to!

Have any novellas lined up to read next month?

Getting Ready for Novellas in November!

Novellas: “all killer, no filler”

~Joe Hill

For the fourth year in a row, Cathy of 746 Books and I are celebrating the art of the short* book by co-hosting Novellas in November as a month-long challenge. This time we have five prompts, adapted from ones commonly used for Nonfiction November. (*A reminder that we suggest 200 pages as the upper limit for a novella.)

Here’s the schedule:

Week 1 (starts Wednesday 1 November): My Year in Novellas

- During this partial week, tell us about any novellas you have read since last NovNov.

Week 2 (starts Monday 6 November): What Is a Novella?

- Ponder the definition, list favourites, or choose ones you think best capture the ‘spirit’ of a novella.

Week 3 (starts Monday 13 November): Broadening My Horizons

- Pick your top novellas in translation and think about new genres or authors you’ve been introduced to through novellas.

Week 4 (starts Monday 20 November): The Short and the Long of It

- Pair a novella with a nonfiction book or novel that deals with similar themes or topics.

Week 5 (starts Monday 27 November): New to My TBR

- In the last few days, talk about the novellas you’ve added to your TBR since the month began.

We also have two buddy read options, one contemporary and one classic. Please join us in reading one or both at any time in November!

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo (2023) is on this year’s Booker Prize longlist; whether or not it advances to the shortlist on Thursday, it promises to be a one-of-a-kind debut novel about an eleven-year-old girl coming to terms with the loss of her mother and becoming deeply involved in the world of competitive squash.

A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf (1929), an extended essay about the conditions necessary for women’s artistic achievement, is based on lectures she delivered at Cambridge’s women’s colleges. This feminist classic is in print or can be freely read online (Internet Archive or Project Gutenberg Canada).

It’s always a busy month in the blogging world, what with Nonfiction November, German Literature Month, and Margaret Atwood Reading Month. Why not search your shelves and/or local library for novellas that count towards multiple challenges? You might also consider participating in Annabel’s Beryl Bainbridge Reading Week (the 18th through 26th) as most of Bainbridge’s novels were under 200 pages.

We’re looking forward to having you join us! From 1 November there will be a pinned post on my site from which you can join the link-up. Keep in touch via Twitter (@cathy746books) and Instagram (@cathy_746books), and feel free to use the terrific feature images Cathy has made plus our new hashtag, #NovNov23.

Novellas in November 2022: That’s a Wrap!

This was Cathy’s and my third year co-hosting Novellas in November. We’ve done our best keeping up with your posts, which Cathy has collected as links on her master post.

The challenge seemed doomed at points, what with my bereavement and Cathy catching Covid a second time, but we persisted! At last count, we had 42 bloggers who took part this year, contributing just over 150 posts covering some 170+ books.

Ten of us read our chosen buddy read, Foster by Claire Keegan (with four bloggers reading Keegan’s Small Things Like These also/instead). I’ve gathered the review links here.

Our next most popular novella was a recent release, Maureen [Fry and the Angel of the North] by Rachel Joyce, which was reviewed four times. Other books highlighted more than once were Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, Mrs Caliban, The Swimmers, The Time Machine, Winter in Sokcho, Ti Amo, Body Kintsugi, Notes on Grief, and Another Brooklyn.

Thank you all for being so engaged with #NovNov22! We’ll see you back here next year.

For Thy Great Pain… and Ti Amo for #NovNov22

On Friday evening we went to see Aqualung give his first London show in 12 years. (Here’s his lovely new song “November.”) I like travel days because I tend to get loads of reading done on my Kindle, and this was no exception: I read both of the below novellas, plus two-thirds of a poetry collection. Novellas aren’t always quick reads, but these were.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie (2023)

Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on when she posits that Margery visited Julian in her cell and took into safekeeping the manuscript of her “shewings.” I finished reading Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love earlier this year and, apart from a couple of biographical details (she lost her husband and baby daughter to an outbreak of plague, and didn’t leave her cell in Norwich for 23 years), this added little to my experience of her work.

Two female medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, are the twin protagonists of Mackenzie’s debut. She allows each to tell her life story through alternating first-person strands that only braid together very late on when she posits that Margery visited Julian in her cell and took into safekeeping the manuscript of her “shewings.” I finished reading Julian’s Revelations of Divine Love earlier this year and, apart from a couple of biographical details (she lost her husband and baby daughter to an outbreak of plague, and didn’t leave her cell in Norwich for 23 years), this added little to my experience of her work.

I didn’t know Margery’s story, so found her sections a little more interesting. A married mother of 14, she earned scorn for preaching, prophesying and weeping in public. Again and again, she was told to know her place and not dare to speak on behalf of God or question the clergy. She was a bold and passionate woman, and the accusations of heresy were no doubt motivated by a wish to see her humiliated for claiming spiritual authority. But nowadays, we would doubtless question her mental health – likewise for Julian when you learn that her shewings arose from a time of fevered hallucination. If you’re new to these figures, you might be captivated by their bizarre life stories and religious obsession, but I thought the bare telling was somewhat lacking in literary interest. (Read via NetGalley) [176 pages]

Coming out on January 19th from Bloomsbury.

Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik (2020; 2022)

[Translated from the Norwegian by Martin Aitken; Archipelago Books]

Ørstavik wrote this in the early months of 2020 while she was living in Milan with her husband, Luigi Spagnol, who was her Italian publisher as well as a painter. They had only been together for four years and he’d been ill for half of that. The average life expectancy for someone who had undergone his particular type of pancreatic cancer surgery was 15–20 months; “We’re at fifteen months now.” Indeed, Spagnol would die in June 2020. But Ørstavik writes from that delicate in-between time when the outcome is clear but hasn’t yet arrived:

Ørstavik wrote this in the early months of 2020 while she was living in Milan with her husband, Luigi Spagnol, who was her Italian publisher as well as a painter. They had only been together for four years and he’d been ill for half of that. The average life expectancy for someone who had undergone his particular type of pancreatic cancer surgery was 15–20 months; “We’re at fifteen months now.” Indeed, Spagnol would die in June 2020. But Ørstavik writes from that delicate in-between time when the outcome is clear but hasn’t yet arrived:

What’s real is that you’re still here, and at the same time, as if embedded in that, the fact that soon you’re going to die. Often I don’t feel a thing.

She knows, having heard it straight from his doctor’s lips, that her husband is going to die in a matter of months, but he doesn’t know. And now he wants to host a New Year’s Eve party, as is their annual tradition. Ørstavik skips between the present, the couple’s shared past, and an incident from her recent past that she hasn’t yet told anyone else: not long ago, while in Mexico for a literary festival, she fell in love with A., her handler. And while she hasn’t acted on that, beyond a kiss on the cheek, it’s smouldering inside her, a secret from the husband she still loves and can’t bear to hurt. Novels are where she can be most truthful, and she knows the one she needs to write will be healing.

There are many wrenching scenes and moments here, but it’s all delivered in a fairly flat style that left little impression on me. I wonder if I’d appreciate her fiction more. (Read via Edelweiss) [124 pages]

Miscellaneous Novellas: Jungle Nama, The Magic Pudding, Tree Glee (#NovNov22)

Here’s a random trio of short books I read earlier and haven’t managed to review until now. Novellas in November is a deliberately wide-ranging challenge, taking in almost any genre you care to read – here I have a retold fable, a bizarre children’s classic, and a self-help work celebrating our connection with trees. I’ll do a couple more of these miscellaneous round-ups before the end of the month.

Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sunderban by Amitav Ghosh (2021)

My first from Ghosh. It’s a retelling in verse of a local Indian legend about Dhona, a greedy merchant who arrives in the mangrove swamps to exploit their resources. To gain wealth he is willing to sacrifice his destitute cousin, Dhukey, to placate Dokkhin Rai, a jungle-dwelling demon that takes the form of a man-eating tiger.

My first from Ghosh. It’s a retelling in verse of a local Indian legend about Dhona, a greedy merchant who arrives in the mangrove swamps to exploit their resources. To gain wealth he is willing to sacrifice his destitute cousin, Dhukey, to placate Dokkhin Rai, a jungle-dwelling demon that takes the form of a man-eating tiger.

However, Dhukey’s mother, distrustful of their cousin, prepared her son for trouble, telling him that if he calls on the goddess Bon Bibi in dwipodi-poyar (rhyming couplets of 24 syllables), she will rescue him. I loved this idea of poetry itself saving the day.

The legend is told, then, in that very Bengali verse style. The insistence on rhyme sometimes necessitates slightly silly word choices, but the text feels very musical. Beyond the fairly obvious messages of forgiveness—

But you must forgive him, rascal though he is;

to hate forever is to fall into an abyss.

—and not grasping for more than you need—

All you need do, is be content with what you’ve got;

to be always craving more, is a demon’s lot.

—I appreciated the idea of ordered verse replicating, or even creating, the order of nature:

Thus did Bon Bibi create a dispensation,

that brought peace to the beings of the Sundarban;

every creature had a place, every want was met,

all needs were balanced, like the lines of a couplet.

With illustrations by Salman Toor. (Public library) [79 pages]

The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay (1918)

This is one of the stranger books I’ve ever read. I happened to see it on Project Gutenberg and downloaded it pretty much for the title alone, without knowing anything about it. It’s an obscure Australian children’s chapter book peopled largely by talking animals. Bill Barnacle (a human), Bunyip Bluegum (a koala bear) and Sam Sawnoff (a penguin) come into possession of a magical pudding by the name of Albert. Cut into the puddin’ as often as you like for servings of steak and kidney pudding and apple dumpling – or your choice from a limited range of other comforting savoury and sweet dishes – and he simply regenerates.

This is one of the stranger books I’ve ever read. I happened to see it on Project Gutenberg and downloaded it pretty much for the title alone, without knowing anything about it. It’s an obscure Australian children’s chapter book peopled largely by talking animals. Bill Barnacle (a human), Bunyip Bluegum (a koala bear) and Sam Sawnoff (a penguin) come into possession of a magical pudding by the name of Albert. Cut into the puddin’ as often as you like for servings of steak and kidney pudding and apple dumpling – or your choice from a limited range of other comforting savoury and sweet dishes – and he simply regenerates.

Naturally, others want to get their hands on this handy source of bounteous food, and the characters have to fend off would-be puddin’-snatchers such as a possum and a wombat and even take their case before a judge. The four chapters are called “Slices,” there are lots of songs reminiscent of Edward Lear, and the dialogue often veers into the farcical:

“‘You can’t wear hats that high, without there’s puddin’s under them,’ said Bill. ‘That’s not puddin’s,’ said the Possum; ‘that’s ventilation. He wears his hat like that to keep his brain cool.’”

I did find it all amusing, but also inane, such that I don’t necessarily think it earns its place as a rediscovered classic. It didn’t help that I then borrowed a copy of the book from the library and found that it was a terribly reproduced “Alpha Editions” version in Comic Sans with distorted illustrations and no line breaks in the songs. (Public library) [169 pages]

Tree Glee: How and Why Trees Make Us Feel Better by Cheryl Rickman (2022)

This is a small-format coffee table self-help book for nature lovers. It affirms something that many of us know intuitively: being around trees improves our mood and our health. Rickman looks at this from a psychological and a cultural perspective, and talks about her own love of trees and how it helped her get through difficult times in life such as when she lost her mum when she was a teenager. She includes some practical ideas for how to spend more time in nature and how we can fight to preserve trees. Unfortunately, a lot of the information was very familiar to me from books such as Rooted by Lyanda Lynn Haupt and Losing Eden by Lucy Jones – for a long time, forest bathing was one of the themes that kept recurring across my reading – such that this felt like an unnecessary rehashing, illustrated with stock photographs that are nice enough to look at but don’t add anything. [182 pages]

This is a small-format coffee table self-help book for nature lovers. It affirms something that many of us know intuitively: being around trees improves our mood and our health. Rickman looks at this from a psychological and a cultural perspective, and talks about her own love of trees and how it helped her get through difficult times in life such as when she lost her mum when she was a teenager. She includes some practical ideas for how to spend more time in nature and how we can fight to preserve trees. Unfortunately, a lot of the information was very familiar to me from books such as Rooted by Lyanda Lynn Haupt and Losing Eden by Lucy Jones – for a long time, forest bathing was one of the themes that kept recurring across my reading – such that this felt like an unnecessary rehashing, illustrated with stock photographs that are nice enough to look at but don’t add anything. [182 pages]

With thanks to Welbeck for the free copy for review.

Body Kintsugi by Senka Marić: A Peirene Press Novella (#NovNov22)

This is my eleventh translated novella from Peirene Press* and, in my opinion, their best yet. It’s an intense work of autofiction about two years of hellish treatment for breast cancer, all the more powerful due to the second-person narration that displaces the pain from the protagonist and onto the reader.

This is a story about the body. Its struggle to feel whole while reality shatters it into fragments. The gash goes from the right nipple towards your back, and after five centimetres makes a gentle curve up and continues to your armpit. It’s still fresh and red.

How does the story crumbling under your tongue and refusing to take on a firm shape begin to be told?

You knew on that day, sixteen years ago, when your mother’s diagnosis was confirmed, that you’d get cancer?

Or

Ever since that day, sixteen years ago, when your mother’s diagnosis was confirmed, that you’d never get cancer?

Both are equally true.

In 2014, just a couple of months after her husband leaves her – making her, in her early forties, a single mother to a son and a daughter – she discovers a lump in her right breast.

In 2014, just a couple of months after her husband leaves her – making her, in her early forties, a single mother to a son and a daughter – she discovers a lump in her right breast.

As she endures five operations, chemotherapy and adjuvant therapies, as well as endless testing and hospital stays, her mind keeps going back to her girlhood and adolescence, especially the moments when she felt afraid or ashamed. Her father, alcoholic and perpetually ill, made her feel like she was an annoyance to him.

Coming of age in a female body was traumatic in itself; now that same body threatens to kill her. Even as she loses the physical signs of femininity, she remains resilient. Her body will document what she’s been through: “Perfectly sculpted through all your defeats, and your victories. The scars scrawled on it are the map of your journey. The truest story about you, which words cannot grasp.”

As forthright as it is about the brutality of cancer treatment, the novella can also be creative, playful and even darkly comic.

Things you don’t want to think about:

Your children

Your boobs

Your cancer

Your bald head

Your death

Almost unbearable nausea delivers her into a new space: “Here, the only colours are black and red. You’re lost in a vast hotel. However hard you try, you can’t count the floors.” One snowy morning, she imagines she’s being visited by a host of Medusa-like women in long black dresses who minister to her. Whether it’s a dream or a medication-induced hallucination, it feels mystical, like she’s part of a timeless lineage of wise women. The themes, tone and style all came together here for me, though I can see how this book might not be for everyone. I have a college friend who’s going through breast cancer treatment right now. She’s only 40. She was diagnosed in the summer and has already had surgery and a few rounds of chemo. I wonder if this book is just what she would want to read right now … or the last thing she would want to think about. All I can do is ask.

(Translated from the Bosnian by Celia Hawkesworth) [165 pages]

With thanks to Peirene Press for the free copy for review.

*Other Peirene Press novellas I’ve reviewed:

Mr. Darwin’s Gardener by Kristina Carlson

The Looking-Glass Sisters by Gøhril Gabrielsen

Ankomst by Gøhril Gabrielsen

Dance by the Canal by Kerstin Hensel

The Last Summer by Ricarda Huch

Snow, Dog, Foot by Claudio Morandini

Her Father’s Daughter by Marie Sizun

The Orange Grove by Larry Tremblay

The Man I Became by Peter Verhelst

Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

This came out in May last year – I pre-ordered it from Waterstones with points I’d saved up, because I’m that much of a fan – and it’s rare for me to reread something so soon, but of course it took on new significance for me this month. Like me, Adichie lived on a different continent from her family and so technology mediated her long-distance relationships. She saw her father on their weekly Sunday Zoom on June 7, 2020 and he appeared briefly on screen the next two days, seeming tired; on June 10, he was gone, her brother’s phone screen showing her his face: “my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose.”

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

The first (and so far only) fiction by the poet and 2020 Nobel Prize winner, this is a curious little story that imagines the inner lives of infant twins and closes with their first birthday. Like Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, it ascribes to preverbal beings thoughts and wisdom they could not possibly have. Marigold, the would-be writer of the pair, is spiky and unpredictable, whereas Rose is the archetypal good baby.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head.

A lesser-known Booker Prize winner that we read for our book club’s women’s classics subgroup. My reading was interrupted by the last-minute trip back to the States, so I ended up finishing the last two-thirds after we’d had the discussion and also watched the movie. I found I was better able to engage with the subtle story and understated writing after I’d seen the sumptuous 1983 Merchant Ivory film: the characters jumped out for me much more than they initially had on the page, and it was no problem having Greta Scacchi in my head. Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)

Various writers and artists contributed these graphic shorts, so there are likely to be some stories you enjoy more than others. “The Ghost of Kyiv” is about a mythical hero from the early days of the Russian invasion who shot down six enemy planes in a day. I got Andy Capp vibes from “Looters,” about Russian goons so dumb they don’t even recognize the appliances they haul back to their slum-dwelling families. (Look, this is propaganda. Whether it comes from the right side or not, recognize it for what it is.) In “Zmiinyi Island 13,” Ukrainian missiles destroy a Russian missile cruiser. Though hospitalized, the Ukrainian soldiers involved – including a woman – can rejoice in the win. “A pure heart is one that overcomes fear” is the lesson they quote from a legend. “Brave Little Tractor” is an adorable Thomas the Tank Engine-like story-within-a-story about farm machinery that joins the war effort. A bit too much of the superhero, shoot-’em-up stylings (including perfectly put-together females with pneumatic bosoms) for me here, but how could any graphic novel reader resist this Tokyopop compilation when a portion of proceeds go to RAZOM, a nonprofit Ukrainian-American human rights organization? (Read via Edelweiss)  August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in

August looks back on her coming of age in 1970s Bushwick, Brooklyn. She lived with her father and brother in a shabby apartment, but friendship with Angela, Gigi and Sylvia lightened a gloomy existence: “as we stood half circle in the bright school yard, we saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.” As in