Tag Archives: Pat Kavanagh

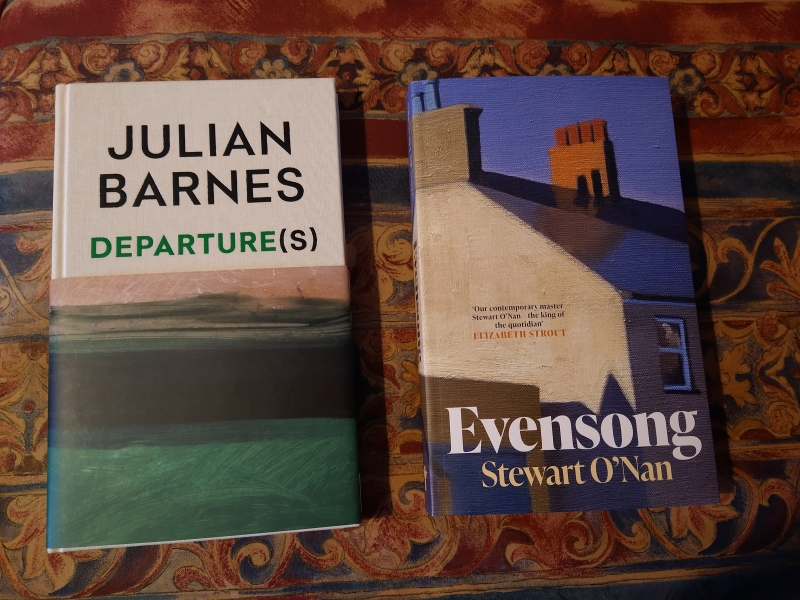

January Releases by Julian Barnes and Stewart O’Nan

These two novels by literary lions (of the UK and USA, respectively) share themes of ageing, loss, and memory, as well as a wry and gently melancholy tone. I’ve read 23 books by Julian Barnes, some of them twice; Stewart O’Nan has also published twenty-some books, but was a new author for me.

Departure(s) by Julian Barnes (2026)

“That’s what I’ve been after all my writing life: the whole story.”

Julian Barnes has been a favourite author of mine since my early twenties. He insists this novella will be his final book. It’s a coy fiction–autofiction mixture featuring the same fixations as much of his work: how time affects relationships and memory, how life gets translated into written evidence, and how we make peace with death. The narrator is one Julian Barnes, a writer approaching age 80 and adjusting to a recent diagnosis of a non-life-threatening blood cancer. The ostensible point is to retell his Oxford University friends Stephen and Jean’s two-stage romance: they were college sweethearts but married other people; then Julian reintroduced them in their sixties and they married – but it didn’t last.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume.

He parcels out bits of this story in between pondering involuntary autobiographical memory (IAM), his “incurable but manageable” condition, and his possible legacy. He hopes he’ll be exonerated due to waiting until Stephen and Jean were dead to write about them and adopting Jean’s old Jack Russell terrier, Jimmy. His late wife, Pat Kavanagh, is never far from his thoughts, and he documents other losses among his peers, including Martin Amis (d. 2023 – for a short book, this is curiously dated, as if it hung around for years unfinished). There are also, as one would expect from Barnes, occasional references to French literature. Confident narration gives the sense of an author in full control of his material. Yet I found much of it tedious. He’s addressed subjectivity much more originally in other works, and the various strands here feel like incomplete ideas shoehorned into one volume.

It’s a shame that I had just reread Talking It Over, a glistening voice-led novel of his from 1991, because it showed up the thinness and repetition of much of his recent work. (I even thought I spotted a reference to Talking It Over as Jean is warning Julian not to write about her and Stephen. “I’ll tell you the truth, and don’t you ever fucking use it, not even deeply disguised in some novel where I appear as Jeanette [Gillian?] and Stephen is Stuart.”) I see his oeuvre as a left-skewed bell curve: three of the first four novels are not worth reading and five of the last seven have also been dubious, but with much excellent material in between. It’s been a case of diminishing returns from The Sense of an Ending onwards, but I have many excellent rereads to look forward to. My next two will be A History of the World in 10½ Chapters – a typically playful take on documented history and legend – and Nothing to Be Frightened Of, his forthright memoir about mortality. If you’ve not read Barnes before, this wouldn’t be a bad place to start as you’ll get a taster of his trademark topics and dry wit, but delving into his back catalogue may well prove more rewarding.

With thanks to Jonathan Cape (Penguin) for the free copy for review.

Evensong by Stewart O’Nan (2025)

The comparisons to Kent Haruf and Elizabeth Strout in the press materials and pre-publication reviews are spot on: this is the kind of quiet American novel that appeals for its small-town ambience and cosy community of lovably quirky people with everyday problems. O’Nan grew up in Pittsburgh, the setting for this fourth book in a loose series based around the character Emily Maxwell – I did have a slight feeling of having wandered into a variant of Olive, Again partway through, but it wasn’t a major stumbling block for me. The generally elderly, female members of the Humpty Dumpty Club form a constellation of care: they help each other out by driving to hospital appointments, picking up prescriptions and groceries – and, when worst comes to worst, planning funeral services.

Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.

Often, the short chapters are vignettes starring one or more of the central characters. When Joan has a fall down her stairs and lands in rehab, Kitzi takes over as de facto HDC leader. A musical couple’s hoarding and cat colony become her main preoccupation. Emily deals with family complications I didn’t fully understand for want of backstory, and Arlene realizes dementia is affecting her daily life. Susie, the “baby” of the group at 63, takes in Joan’s cat, Oscar, and meets someone through online dating. The novel covers four months of 2022–23, anchored by a string of holidays (Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas); events such as John Fetterman’s election and ongoing Covid precautions; and the cycle of the Church year.

O’Nan encourages affection for his salt-of-the-earth folk who vote Democrat, support the Steelers and attend liberal Protestant churches as a matter of course. They lead simple lives and cope with failing health with as much dignity as they can. There’s something to be said for celebrating older, ordinary people, who don’t often get a look-in in contemporary fiction. But I struggled with the ensemble nature of the cast – well over halfway through I was still trying to work out who everyone was; it doesn’t help that there are a Gene, a Jean and a Joan – and the extreme verisimilitude. The Humpty Dumpty Club exists in real life, but these women could be your aunt or choir director from Any Town, USA. Were my mother still around, this would be her, running errands and helping neighbours in suburban Pittsburgh, and I would be visiting the area annually. That combination of the mundane and the too close to home conspired to make this more of a slog than expected. I also feel I gleaned no distinct understanding of O’Nan as a writer – especially as other novels of his that I own (The Night Country and A Prayer for the Dying) are classed under horror. I’ll just have to try more.

First published in November 2025 by Atlantic Monthly Press in the USA. With thanks to Grove Press UK for the free copy for review.

While these were much anticipated reads for me, I ultimately found them a little underwhelming. I think I wanted a bit more raging against the dying of the light.

Have you read either or both of these authors? What can you recommend by them, or what will you seek out?

Short, Soul-Soothing Reads for #NovNov24 & #NonfictionNovember: Barnes, Cognetti, Lende, Mann, Nouwen and Winner

After the catastrophic U.S. election results (which we’ve all managed to ignore or normalize so as to keep going with our lives) and a medical crisis with our dear old cat, I’ve been craving literary soul food. These six short nonfiction books have been good companions, promising love, meaning and transcendence in the midst of bereavement and daily routines.

Levels of Life by Julian Barnes (2013)

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning Question 7, a similar hybrid work that pulls it off better. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

Barnes was a favourite author in my twenties and thirties, though I’ve had less success with his recent work. He wrote a few grief-soaked books in the wake of the death of his wife, celebrated literary agent Pat Kavanagh*. I had this mistaken for a different one (Through the Window, I think?) that I had enjoyed more. No matter; it was still interesting to reread this triptych of auto/biographical essays. The final, personal piece, “The Loss of Depth,” is a classic of bereavement literature on par with C.S. Lewis’s A Grief Observed; I would happily take it as a standalone pamphlet. Its every word rings true, especially the sense of duty as the lost one’s “principal rememberer.” But the overarching ballooning metaphor, and links with early French aerial photographer Nadar and Colonel Fred Burnaby, aeronaut and suitor of Sarah Bernhardt, don’t convince. The strategy feels like a rehearsal for Richard Flanagan’s Baillie Gifford Prize-winning Question 7, a similar hybrid work that pulls it off better. (Little Free Library) [118 pages]

*In spring 2008, I attended a talk by John Irving at King’s College, London, where I worked in library services for five years. Barnes and Kavanagh were in the front row and embraced Irving before the start. I was floored to hear of Kavanagh’s death later that year because she’d looked so well. It was a fast-acting brain tumour that felled her just 37 days after diagnosis.

Without Ever Reaching the Summit by Paolo Cognetti (2018; 2020)

[Translated from the Italian by Stash Luczkiw]

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard. Cognetti struggles with altitude sickness and the fare: “I tried salted yak butter tea for the first time—nauseating if you thought you were drinking tea, good and refreshing if you thought you were drinking broth.” He and his companions fancifully decide that Kanjiroba, the lovable stray dog who joins their party, is a reincarnation of Matthiessen. I have limited tolerance for travel books’ episodic combinations of nature descriptions, anthropological observations, and the rigours of the nomadic lifestyle. The same was true here, but the slight spiritual aspect and references to The Snow Leopard lifted it. (Public library) [135 pages]

Part pilgrimage and part 40th birthday treat, Cognetti’s October 2017 Himalayan trek through Dolpo (a Nepalese plateau at the Tibetan border) would also somewhat recreate Peter Matthiessen’s The Snow Leopard. Cognetti struggles with altitude sickness and the fare: “I tried salted yak butter tea for the first time—nauseating if you thought you were drinking tea, good and refreshing if you thought you were drinking broth.” He and his companions fancifully decide that Kanjiroba, the lovable stray dog who joins their party, is a reincarnation of Matthiessen. I have limited tolerance for travel books’ episodic combinations of nature descriptions, anthropological observations, and the rigours of the nomadic lifestyle. The same was true here, but the slight spiritual aspect and references to The Snow Leopard lifted it. (Public library) [135 pages]

Find the Good: Unexpected Life Lessons from a Small-Town Obituary Writer by Heather Lende (2015)

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Lende is a journalist in isolated Haines, Alaska (population: 2,000). There’s a plucky motivational bent to these mini-essays about small-town life and death. In writing obituaries for normal, flawed people, she is reminded of what matters most: family (she’s a mother of five, one adopted, and a grandmother; she includes beloved pets in this category) and vocation. The title phrase is the motto she lives by. “I believe gratitude comes from a place in your soul that knows the story could have ended differently, and often does, and I also know that gratitude is at the heart of finding the good in this world—especially in our relationships with the ones we love.” The anecdotes and morals are sweet if not groundbreaking. The pocket-sized hardback might appeal to readers of Anne Lamott and Elizabeth Strout. (Birthday gift from my wish list, secondhand) [162 pages]

Do Not Be Afraid: The joy of waiting in a time of fear by Rachel Mann (2024)

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

This is the Archbishop of York’s Advent Book 2024; I read it early because, pre-election, I yearned for its message of courage and patience. We need it all the more now. The bite-sized essays are designed to be read one per day from the first Sunday of Advent through to Christmas Day. Often they include a passage of scripture or poetry (including some of Mann’s own) for meditation, and each entry closes with a short prayer and a few questions for discussion or private contemplation. The topics are a real variety but mostly draw on the author’s own experiences of waiting and suffering: medical appointments and Covid isolation as well as the everyday loneliness of being single and the pain of coping with chronic illness. She writes about sitting with parishioners as they face death and bereavement. But there are also pieces inspired by popular culture – everything from Strictly to Quentin Tarantino.

Mann has written several previous Lent course books based on films. I’ve read her work in multiple genres (poetry: A Kingdom of Love and Eleanor Among the Saints; literary criticism: In the Bleak Midwinter; memoir: Dazzling Darkness; fiction: The Gospel of Eve); she is such a versatile writer, and with a fascinating story as a trans priest. Sombre yet hopeful, this is recommended seasonal reading. [114 pages]

With thanks to SPCK for the free copy for review.

The Inner Voice of Love: A Journey through Anguish to Freedom by Henri J. M. Nouwen (1997)

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Anguish is a strong word; I haven’t done any biographical digging to figure out what was going on in Nouwen’s life to prompt it, but apparently this secret journal came out of a lost relationship. (I wonder if it could have been a homosexual attachment. Nouwen was a Dutch Roman Catholic priest who became the pastor of a community for disabled adults in Canada.) He didn’t publish for another eight years but friends encouraged him to let his experience aid others. The one- or two-page reflections are written in the second person, so they feel like a self-help pep talk. The recurring themes are overcoming abandonment and rejection, relinquishing control, and trusting in God’s love and faithfulness. “You must stop being a pleaser and reclaim your identity as a free self.” The point about needing to integrate rather than sideline psychological pain is one I’m sure any therapist would affirm. Nouwen writes that a new spirituality of the body is necessary. This was a comforting bedside book with lots of passages that resonated. (Free – withdrawn from church theological library) [98 pages]

Mudhouse Sabbath: An Invitation to a Life of Spiritual Discipline by Lauren F. Winner (2003)

After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

After Winner converted from Orthodox Judaism to Christianity, she found that she missed how Jewish rituals make routine events sacred. There are Christian sacraments, of course, but this book is about how the wisdom of another tradition might be applied in a new context. “Judaism offers opportunities for people to inhabit and sanctify bodies and bodily practices,” Winner writes. There are chapters on the concept of the Sabbath, wedding ceremonies, prayer and hospitality. Fasting is a particular sticking point for Winner, but her priest encourages her to see it as a way of demonstrating dependence on, and hunger for, God. I most appreciated the sections on mourning and ageing. “Perhaps the most essential insight of the Jewish approach to caring for one’s elderly is that this care is, indeed, an obligation. What Judaism understands is that obligations are good things. They are the very bedrock of the Jew’s relationship to God, and they govern some of the most fundamental human relationships”. By the way, Mudhouse is Winner’s local coffeehouse, so she believes these disciplines can be undertaken anywhere. (Secondhand – Awesomebooks.com) [142 pages]

Adventures in Rereading: Julian Barnes and Jennifer Egan

My last two rereads ended up being as good as or better than they had been the first time around; these two, however, failed to live up to my memory of them, one of them dramatically so. My increased literary experience and/or the advance of years meant these works felt less fresh than they did the first time around.

Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes (1984)

Barnes is in my trio of favorite authors, along with A. S. Byatt and David Lodge. He’s an unapologetic intellectual and a notable Francophile who often toggles between England and France, especially in his essays and short stories. This was his third novel and riffs on the life and works of Gustave Flaubert, best known for Madame Bovary.

Barnes is in my trio of favorite authors, along with A. S. Byatt and David Lodge. He’s an unapologetic intellectual and a notable Francophile who often toggles between England and France, especially in his essays and short stories. This was his third novel and riffs on the life and works of Gustave Flaubert, best known for Madame Bovary.

Odd-numbered chapters build a straightforward narrative as Geoffrey Braithwaite, a widower, retired doctor and self-described “senile amateur scholar,” travels to Rouen for five days to see the sites associated with Flaubert and becomes obsessed with determining which of two museum-held stuffed parrots Flaubert used as his inspiration while writing the story “A Simple Heart.” Even-numbered chapters, however, throw in a variety of different formats: a Flaubert chronology, a bestiary, an investigation of the contradictory references to Emma Bovary’s eye color, a dictionary of accepted ideas, an examination paper, and an imagined prosecutor’s case against the writer.

There are themes and elements here that recur in much of Barnes’s later work:

- History – what remains of a life? (“He died little more than a hundred years ago, and all that remains of him is paper.”)

- Love versus criticism of one’s country (“The greatest patriotism is to tell your country when it is behaving dishonourably, foolishly, viciously.”)

- Time and its effects on relationships and memory

- How life is transmuted into art

- Languages and wordplay

- Bereavement

Indeed, I was most struck by Chapter 13, “Pure Story,” in which Dr. Braithwaite finally comes clean about his wife’s death and the complications of their relationship. Barnes writes about grief so knowingly and with such nuance, yet his own wife, Pat Kavanagh, didn’t die until 2008. Much of what he’s published since then has dwelt on loss, but more than two decades earlier he was already able to inhabit that experience in his imagination.

As a 22-year-old graduate student, I gobbled this up even though I knew very little about French literature and history and hadn’t yet read any Flaubert. I wasn’t quite as dazzled by the literary and biographical experimentation this time. While I still admired the audacity of the novel, I wouldn’t call it a personal favorite any longer. I think others of Barnes’s works will resonate for me more on a reread.

My original rating (c. 2006):

My rating now:

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan (2010)

This makes up a pleasing pair as it shares Barnes’s experimentation with form and meditation on time. Before my reread I only remembered that it was about washed-up musicians and that there was one second-person chapter and another told as a PowerPoint presentation. Looking back at my original review, I see I was impressed by how Egan interrogated “society’s obsession with youth and celebrity, the moments of decision that can lead to success or to downfall … and the way time (the ‘goon’ of the title) and failure can wear away at one’s identity.” Back then I called the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “achingly fresh, contemporary and postmodern. It is, in fact, so up-to-the-minute that one wonders how long that minute can last.” I was right to question its enduring appeal: this time I found the book detached, show-offy and even silly in places, and the characterization consistently left me cold.

This was probably the first linked short story collection I ever read (now a favorite subgenre), and the first time I’d encountered second-person narration in fiction, so it’s no wonder I was intrigued. “Each chapter involves a very clever shift in time period and point of view,” I noted in 2011. This time, though, I found the 1970s–2020s timeline unnecessarily diffuse, and I was so disinterested in most of the characters – kleptomaniac PA Sasha, post-punk music producer Bennie, musician turned janitor turned children’s performer Scotty, a disgraced journalist, a starlet, and so on – that I didn’t care to revisit them.

This was probably the first linked short story collection I ever read (now a favorite subgenre), and the first time I’d encountered second-person narration in fiction, so it’s no wonder I was intrigued. “Each chapter involves a very clever shift in time period and point of view,” I noted in 2011. This time, though, I found the 1970s–2020s timeline unnecessarily diffuse, and I was so disinterested in most of the characters – kleptomaniac PA Sasha, post-punk music producer Bennie, musician turned janitor turned children’s performer Scotty, a disgraced journalist, a starlet, and so on – that I didn’t care to revisit them.

The chapter in which Scotty catches a fish and takes it into Bennie’s office was a favorite, along with the PowerPoint presentation Sasha’s daughter puts together on the great pauses of rock music (while also revealing a lot about her family dynamic), but I found the segment on PR attempts to burnish an African general’s reputation far-fetched and ended up mostly skimming five of the last six chapters.

This was a buddy read with Laura T. (see her review); we came to similar conclusions: this may have felt fresh and even prescient about technology in 2010–11, but it didn’t stand up to a reread; still, we’ll keep our copies if just for the 75-page PowerPoint presentation.

Note: Egan has said that her next project is a companion piece to Goon Squad that uses a similar structure and follows some of its peripheral characters into new territory. Based on this rereading experience, I don’t think I’ll seek out the sequel.

My original rating (June 2011):

My rating now:

To reread next: Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer and On Beauty by Zadie Smith