Recent Poetry Releases by Anderson, Godden, Gomez, Goodan, Lewis & O’Malley

Nature, social engagement, and/or women’s stories are linking themes across these poetry collections, much as they vary in their particulars. After my brief thoughts, I offer one sample poem from each book.

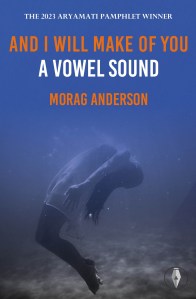

And I Will Make of You a Vowel Sound by Morag Anderson

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

Morag Anderson was the 2023 Makar of the Federation of Writers in Scotland. She won the Aryamati Pamphlet Prize for this second chapbook of 25 poems. Her subjects are ordinary people: abandoned children, a young woman on a council estate, construction workers, and a shoplifter who can’t afford period products. The verse is rich with alliteration, internal rhymes and neologisms. Although sub/urban settings predominate, there are also poems dedicated to birds and to tracking the seasons’ march along a river. There is much sibilance to “Little Wren,” while “Cormorant Speaks” enchants with its fresh compound words: “Barefoot in mudslick streambeds I pathpick over rotsoft limbs, wade neckdeep in suncold loch”. “No Ordinary Tuesday, 2001” is about 9/11 and “None of the Nine Were There” expresses feminist indignation at the repeal of Roe v. Wade: “all nine were busy / stitching rules into the seams / of bleeding wombs.” A trio of poems depicts the transformation of matrescence: “Long after my shelterbody shucks / her reluctant skull / from my shell, // her foetal cells— / rosefoamed in my core— / migrate to mend my flensed heart.” Impassioned and superbly articulated. A confident poet whose work I was glad to discover.

With thanks to Fly on the Wall Press for the free copy for review.

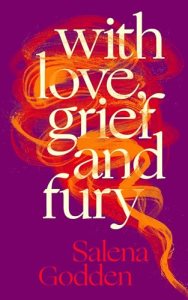

With Love, Grief and Fury by Salena Godden

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

“In a time of apathy, / hope is a revolutionary act”. I knew Godden from her hybrid novel Mrs Death Misses Death, but this was my first taste of the poetry for which she is better known. The title gives a flavour of the variety in tone. Poems arise from environmental anxiety; feminist outrage at discrimination and violence towards women; and personal experiences of bisexuality, being childfree (“Book Mother” and “Egg and Spoon Race”), and entering perimenopause (“Evergreen Tea”). Solidarity and protest are strategies for dispelling ignorance about all of the above. Godden also marks the rhythms of everyday life for a single artist, and advises taking delight in life’s small pleasures. The social justice angle made it a perfect book for me to read portions of on the Restore Nature Now march through London in June …

… and while volunteering as an election teller at a polling station last week. It contains 81 poems (many of them overlong prose ones), making for a much lengthier collection than I would usually pick up. The repetition, wordplay and run-on sentences are really meant more for performance than for reading on the page, but if you’re a fan of Hollie McNish or Kae Tempest, you’re likely to enjoy this, too.

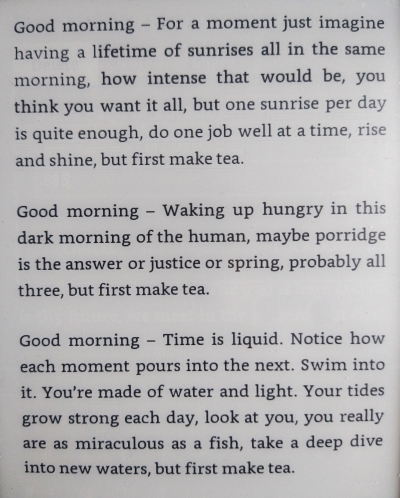

An excerpt from “But First Make Tea”

(Read via NetGalley) Published in the UK by Canongate Press.

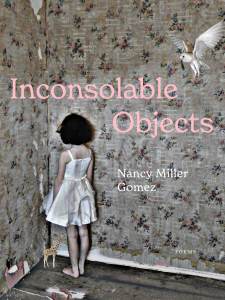

Inconsolable Objects by Nancy Miller Gomez

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

Nancy Miller Gomez’s debut collection recalls a Midwest girlhood of fairground rides and lake swimming; tornadoes and cicadas. But her remembered Kansas is no site of rose-tinted nostalgia. “Missing History” notes how women’s stories, such as her grandmother’s, are lost to time. A pet snake goes missing and she imagines it haunting her mother. In “Tilt-A-Whirl,” her older sister’s harmless flirtation with a ride operator turns sinister. “Mothering,” likewise, eschews the cosy for images of fierce protection. The poet documents the death of her children’s father and abides with a son enduring brain scans and a daughter in recovery from heroin addiction. She also takes ideas from the headlines, with poems about the Ukraine invasion and species extinction. There is a prison setting in two in a row – she has taught Santa Cruz County Jail poetry workshops. The alliteration and slant rhymes are to die for, and I love the cover (Owl Collage by Alexandra Gallagher) and frequent bird metaphors. This also appeared on my Best Books from the First Half of 2024 list. [My full review is on Goodreads.]

With thanks to publicist Sarah Cassavant (Nectar Literary) and YesYes Books for the e-copy for review.

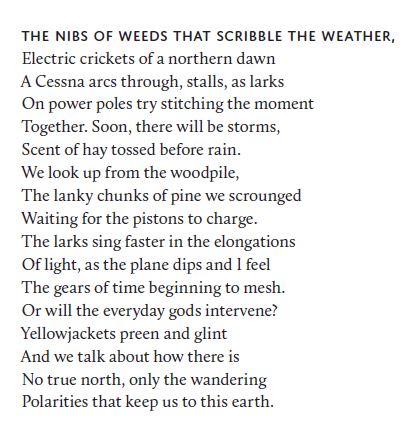

In the Days that Followed by Kevin Goodan

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

These 41 poems, each limited to one stanza and one page, are named for their first lines, like hymns. With their old-fashioned lyricism and precise nature vocabulary, they are deeply rooted in place and animated by frequent rhetorical questions. Birds and fields, livestock and wildfires: Goodan marks where human interest and the natural world meet, or sometimes clash. He echoes Emily Dickinson (“After great patience, a small bird comes”) and also reminds me of Keith Taylor, whose upcoming collection I’ve reviewed for Shelf Awareness. The pages are rain-soaked and ghost-haunted, creating a slightly melancholy atmosphere. Unusual phrasing and alliteration stand out: “on the field / A fallow calm falls / Leaving the soil / To its feraling.” He’s a new name for me though this is his seventh collection; I’d happily read more. [After I read the book I looked at the blurb on Goodreads. I got … none of that from my reading, so be aware that it’s very subtle.]

With thanks to Alice James Books for the e-copy for review.

From Base Materials by Jenny Lewis

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

This nicely ties together many of the themes covered by the other collections I’ve discussed: science and nature imagery, ageing, and social justice pleas. But Lewis adds in another major topic: language itself, by way of etymology and translation. “Another Way of Saying It” gives the origin of all but incidental words in parentheses. The “Tales from Mesopotamia” are from a commissioned verse play she wrote and connect back to her 2014 collection Taking Mesopotamia, with its sequence inspired by The Epic of Gilgamesh. There are also translations from the Arabic and a long section paraphrases the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, which recalls the books of Ecclesiastes and Job with its self-help aphorisms. Other poems are inspired by a mastectomy, Julian of Norwich, Japanese phrases, and Arthurian legend. The title phrase comes from the Rubaiyat and refers to the creation of humanity from clay. There’s such variety of subject matter here, but always curiosity and loving attention.

“On Translation”

The trouble with translating, for me, is that

when I’ve finished, my own words won’t come;

like unloved step-children in a second marriage,

they hang back at table, knowing their place.

While their favoured siblings hold forth, take

centre stage, mine remain faint, out of ear-shot

like Miranda on her island shore before the boats

came near enough, signalling a lost language;

and always the boom of another surf – pounding,

subterranean, masculine, urgent – makes my words

dither and flit, become little and scattered

like flickering shoals caught up in the slipstream

of a whale, small as sand crabs at the bottom of a bucket,

harmless; transparent as zooplankton.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

This was my first time reading Irish poet Mary O’Malley. Nature looms large in her tenth collection, as in several of the other books I’ve reviewed here, with poems about flora and fauna. “Late Swallow” is a highlight (“your loops and dives leave ripples in the air, / a winged Matisse, painting with scissors”) and the title’s reference is to dogfish – what’s in a name, eh? The meticulous detail in her descriptions made me think of still lifes, as did a mention of an odalisque. Other verse is stimulated by Greek myth, travel to Lisbon, and the Gaelic language. Sections are devoted to pandemic experiences (“Another Plague Season”) and to technology. “The Dig” imagines what future archaeologists will make of our media. I noted end and internal rhymes in “April” and the repeated sounds and pattern of stress of “clean as a quiver of knives.” O’Malley has a light touch but leaves a big impression.

“Holy”

The days lengthen, the sky quickens.

Something invisible flows in the sticks

and they blossom. We learn to let this

be enough. It isn’t; it’s enough to go on.

Then a lull and a clip on my phone

of a small girl playing with a tennis ball

her three-year-old face a chalice brimming

with life, and I promise when all this is over

I will remember what is holy. I will say

the word without shame, and ask if God

was his own fable to help us bear absence,

the cold space at the heart of the atom.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the e-copy for review.

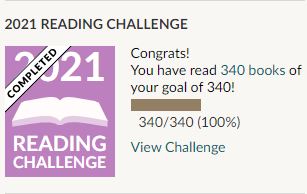

Women’s Prize 2021: Predictions & Eligible Titles

In previous years I’ve been a half-hearted follower of the Women’s Prize – often half or more of the longlist doesn’t interest me – but given that nearly two-thirds of my annual reading is by women, and that I so enjoyed catching up on the previous winners last year, I somehow feel more invested this year. Following literary prizes is among my greatest bookish joys, so this time round I’ve made more of an effort to look back through a year of UK fiction releases by women, whether I’ve read the books or not, and make some informed predictions.

Here is the scope of the prize: “Any woman writing in English – whatever her nationality, country of residence, age or subject matter – is eligible. Novels must be published in the United Kingdom between 1 April in the year the Prize calls for entries, and 31 March the following year, when the Prize is announced.” (Note: no novellas or short stories; the judges are looking for the best work by a woman – or a trans person legally defined as a woman.)

Based on the books by women that I have admired, loved, or found most relevant in 2020‒21, here are my predictions for the longlist, which will be revealed on March 10th (two weeks from today) and will contain 16 titles. I’ve aimed for a balance between new and established voices, and a mix of genres. I link to my reviews where available.

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett

- Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

- Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan

- Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

- Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden

- Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

- Sisters by Daisy Johnson

- Pew by Catherine Lacey

- No One Is Talking about This by Patricia Lockwood – currently reading

- A Burning by Megha Majumdar*

- The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

- Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley**

- Outlawed by Anna North

- Love After Love by Ingrid Persaud

- The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey***

- The Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams

* Not read yet. It seems like this year’s Home Fire.

** Not read yet, but I loved Elmet so much that I’m confident this will be a hit with me, too.

*** Not read yet. I plan to read it, but after its Costa win there’s a long library holds queue.

Note: “The Prize only accepts novels entered by publishers, who may each submit a maximum of two titles per imprint and one title for imprints with a list of five fiction titles or fewer published in a year. Previously shortlisted and winning authors are awarded a ‘free pass’ in addition to a publisher’s general submissions.”

- Because of all the funds the publishers are expected to contribute to the Prize’s publicity at each level of judging, the process unfairly discriminates against small, independent publishers.

Bernardine Evaristo is the chair of judges this year, so I expect a strong showing from BIPOC and LGBTQ authors AND a leaning towards experimental prose, probably even more so than my above list reflects.

Other novels I considered:

Runners-up – books that I enjoyed and would be perfectly happy to see nominated:

- Milk Fed by Melissa Broder – not reviewed yet

- Here Is the Beehive by Sarah Crossan

- The Group by Lara Feigel

- Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller – not reviewed yet

- Artifact by Arlene Heyman

- The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd

- A Town Called Solace by Sue Lawson – not reviewed yet

- Monogamy by Sue Miller

- What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez

- Islands of Mercy by Rose Tremain

Reads that didn’t match up for me, but would be eligible:

- When the Lights Go Out by Carys Bray

- The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

- Tennis Lessons by Susannah Dickey

- The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney (DNF)

- The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin

- Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce

- The Animals in That Country by Laura Jean McKay

- Scenes of a Graphic Nature by Caroline O’Donoghue

- True Story by Kate Reed Petty (DNF)

- Rodham by Curtis Sittenfeld

- The Lamplighters by Emma Stonex – currently reading

- Redhead by the Side of the Road by Anne Tyler

- little scratch by Rebecca Watson

- Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson

Haven’t had a chance to read yet / don’t have access to, so can only list without comment (most likely alternative nominees in bold):

- Against the Loveless World by Susan Abulhawa

- You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

- The Push by Ashley Audrain

- If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

- [The Death of Vivek Oji by Akwaeke Emezi] – Update: would not be eligible according to the new requirement that trans people be legally defined as female; before that regulation was in place, Emezi was longlisted for Freshwater.

- Sea Wife by Amity Gaige

- The Wild Laughter by Caoilinn Hughes

- How We Are Translated by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson

- Consent by Annabel Lyon

- A Crooked Tree by Una Mannion

- The Last Migration by Charlotte McConaghy

- The Art of Falling by Danielle McLaughlin

- His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie

- A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa

- Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan

- Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler

- An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon

- Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

- Jack by Marilynne Robinson – gets a “free pass” entry as MR is a previous winner

- Belladonna by Anbara Salam

- Kololo Hill by Neema Shah

- All Adults Here by Emma Straub

- Friends and Strangers by J. Courtney Sullivan

- Saving Lucia by Anna Vaught

- We Are All Birds of Uganda by Hafsa Zayyan

- How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang

I overlapped with this Goodreads list (which I didn’t look at until after compiling mine) on 28 titles. It erroneously includes The Anthill by Julianne Pachico – not released in the UK until May 2021 – but otherwise has another nearly 50, mostly solid, ideas, such as Luster by Raven Leilani, Blue Ticket by Sophie Mackintosh, and Death in her Hands by Ottessa Moshfegh.

See also Laura’s and Rachel’s predictions.

Any predictions or wishes for the Women’s Prize longlist?

Fairy Tales, Outlaws, Experimental Prose: Three More January Novels

Today I’m featuring three more works of fiction that were released this month, as a supplement to yesterday’s review of Mrs Death Misses Death. Although the four are hugely different in setting and style, and I liked some better than others (such is the nature of reading and book reviewing), together they’re further proof – as if we needed it – that female authors are pushing the envelope. I wouldn’t be surprised to see any or all of these on the Women’s Prize longlist in March.

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin

What happens next for Cinderella?

What happens next for Cinderella?

Grushin’s fourth novel unpicks a classic fairy tale narrative, starting 13.5 years into a marriage when, far from being starry-eyed with love for Prince Roland, the narrator hates her philandering husband and wants him dead. As she retells the Cinderella story to her children one bedtime, it only underscores how awry her own romance has gone: “my once-happy ending has proved to be only another beginning, a prelude to a tale dimmer, grittier, far more ambiguous, and far less suitable for children”. She gathers Roland’s hair and nails and goes to a witch for a spell, but her fairy godmother shows up to interfere. The two embark on a good cop/bad cop act as the princess runs backward through her memories: one defending Roland and the other convinced he’s a scoundrel.

Part One toggles back and forth between flashbacks (in the third person and past tense) and the present-day struggle for the narrator’s soul. She comes to acknowledge her own ignorance and bad behaviour. “All I want is to be free—free of him, free of my past, free of my story. Free of myself, the way I was when I was with him.” In Part Two, as the princess tries out different methods of escape, Grushin coyly inserts allusions to other legends and nursery rhymes: a stepsister lives with her many children in a house shaped like a shoe; the witch tells a variation on the Bluebeard story; the fairy godmother lives in a Hansel and Gretel-like candy cottage; the narrator becomes a maid for 12 slovenly sisters; and so on.

The plot feels fairly aimless in this second half, and the mixture of real-world and fantasy elements is peculiar. I much preferred Grushin’s previous book, Forty Rooms (and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of her chief inspirations). However, her two novels share a concern with how women’s ambitions can take a backseat to their roles, and both weave folktales and dreams into a picture of everyday life. But my favourite part of The Charmed Wife was the subplot: interludes about Brie and Nibbles, the princess’s pet mice; their lives being so much shorter, they run through many generations of a dramatic saga while the narrator (whose name we do finally learn, just a few pages from the end) is stuck in place.

The plot feels fairly aimless in this second half, and the mixture of real-world and fantasy elements is peculiar. I much preferred Grushin’s previous book, Forty Rooms (and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of her chief inspirations). However, her two novels share a concern with how women’s ambitions can take a backseat to their roles, and both weave folktales and dreams into a picture of everyday life. But my favourite part of The Charmed Wife was the subplot: interludes about Brie and Nibbles, the princess’s pet mice; their lives being so much shorter, they run through many generations of a dramatic saga while the narrator (whose name we do finally learn, just a few pages from the end) is stuck in place.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Outlawed by Anna North

I was a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which cobbles together the story of the title character, a bisexual filmmaker, from accounts by the people who knew her best. Outlawed, an alternative history/speculative take on the traditional Western, could hardly be more different. In a subtly different version of the United States, everyone now alive in the 1890s is descended from those who survived a vicious 1830s flu epidemic. The duty to repopulate the nation has led to a cult of fertility and devotion to the Baby Jesus. From her mother, a midwife and herbalist, Ada has learned the basics of medical care, but the causes of barrenness remain a mystery and childlessness is perceived as a curse.

I was a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which cobbles together the story of the title character, a bisexual filmmaker, from accounts by the people who knew her best. Outlawed, an alternative history/speculative take on the traditional Western, could hardly be more different. In a subtly different version of the United States, everyone now alive in the 1890s is descended from those who survived a vicious 1830s flu epidemic. The duty to repopulate the nation has led to a cult of fertility and devotion to the Baby Jesus. From her mother, a midwife and herbalist, Ada has learned the basics of medical care, but the causes of barrenness remain a mystery and childlessness is perceived as a curse.

Ada marries at 17 and fails to get pregnant within a year. After an acquaintance miscarries, rumours start to spread about Ada being a witch. Kicked out by her mother-in-law, she takes shelter first at a convent and then with the Hole in the Wall gang. She’ll be the doctor to this band of female outlaws who weren’t cut out for motherhood and shunned marriage – including lesbians, a mixed-race woman, and their leader, the Kid, who is nonbinary. The Kid is a mentally tortured prophet with a vision of making the world safe for people like them (“we were told a lie about God and what He wants from us”), mainly by, Robin Hood-like, redistributing wealth through hold-ups and bank robberies. Ada, who longs to conduct proper research into reproductive health rather than relying on religious propaganda, falls for another gender nonconformist, Lark, and does what she can to make the Kid’s dream a reality.

Reese Witherspoon choosing this for her Hello Sunshine book club was a great chance for North’s work to get more attention. However, I felt that the ideas behind this novel were more noteworthy than the execution. The similarity to The Handmaid’s Tale is undeniable, though I liked this a bit more. I most enjoyed the medical and religious themes, and appreciated the attention to childless and otherwise unconventional women. But the setup is so condensed and the consequences of the gang’s major heist so rushed that I wondered if the novel needed another 100 pages to stretch its wings. I’ll just have to await North’s next book.

With thanks to W&N for the proof copy for review.

little scratch by Rebecca Watson

I love a circadian narrative and had heard interesting things about the experimental style used in this debut novel. I even heard Watson read a passage from it as part of the Faber Live Fiction Showcase and found it very funny and engaging. But I really should have tried an excerpt before requesting this for review; I would have seen at a glance that it wasn’t for me. I don’t have a problem with prose being formatted like poetry (Girl, Woman, Other; Stubborn Archivist; the prologue of Wendy McGrath’s Santa Rosa; parts of Mrs Death Misses Death), but here it seemed to me that it was only done to alleviate the tedium of the contents.

I love a circadian narrative and had heard interesting things about the experimental style used in this debut novel. I even heard Watson read a passage from it as part of the Faber Live Fiction Showcase and found it very funny and engaging. But I really should have tried an excerpt before requesting this for review; I would have seen at a glance that it wasn’t for me. I don’t have a problem with prose being formatted like poetry (Girl, Woman, Other; Stubborn Archivist; the prologue of Wendy McGrath’s Santa Rosa; parts of Mrs Death Misses Death), but here it seemed to me that it was only done to alleviate the tedium of the contents.

A young woman who, like Watson, works for a newspaper, trudges through a typical day: wake up, get ready, commute to the office, waste time and snack in between doing bits of work, get outraged about inconsequential things, think about her boyfriend (only ever referred to as “my him” – probably my biggest specific pet peeve about the book), and push down memories of a sexual assault. Thus, the only thing that really happens happened before the book even started. Her scratching, to the point of open wounds and scabs, seems like a psychosomatic symptom of unprocessed trauma. By the end, she’s getting ready to tell her boyfriend about the assault, which seems like a step in the right direction.

I might have found Watson’s approach captivating in a short story, or as brief passages studded in a longer narrative. At first it’s a fun puzzle to ponder how these mostly unpunctuated words, dotted around the pages in two to six columns, fit together – should one read down each column, or across each row, or both? – but when all the scattershot words are only there to describe a train carriage filling up or repetitive quotidian actions (sifting through e-mails, pedalling a bicycle), the style soon grates. You may have more patience with it than I did if you loved A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing or books by Emma Glass.

A favourite passage: “got to do this thing again, the waking up thing, the day thing, the work thing, disentangling from my duvet thing, this is something, this is a thing I have to do then,” [appears all as one left-aligned paragraph]

With thanks to Faber & Faber for the free copy for review.

Tomorrow I’ll review three nonfiction works published in January, all on a medical theme.

What recent releases can you recommend?

Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers meets Girl, Woman, Other would be my marketing shorthand for this one. Poet Salena Godden’s debut novel is a fresh and fizzing work, passionate about exposing injustice but also about celebrating simple joys, and in the end it’s wholly life-affirming despite a narrative stuffed full of deaths real and imagined.

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers meets Girl, Woman, Other would be my marketing shorthand for this one. Poet Salena Godden’s debut novel is a fresh and fizzing work, passionate about exposing injustice but also about celebrating simple joys, and in the end it’s wholly life-affirming despite a narrative stuffed full of deaths real and imagined.

What if Death wasn’t the male Grim Reaper stereotype? What if, instead, she was a poor black woman – a bag lady on a bus, or a hospital cleaner? In this playful and lilting story, we learn of Mrs Death’s work via her unwitting medium, Wolf Willeford, who one Christmas Eve goes walking in London’s Brick Lane area and buys an irresistible desk that reveals flashes of historical deaths. Once Mrs Death’s desk (and resentful at not being a piano), it now transmits her stories to Wolf, giving a whole new meaning to the term ghost writer. Wolf compiles and edits her memoirs, which take the form of diary entries, poems, and songs.

It’s never been more stressful to be Death, what with civil war in Syria, school shootings in the USA, and refugees drowning off the coast of France. But although the book’s frame of reference is up to the minute, wrongful deaths are nothing new, so occasional vignettes dramatize untimely demises – especially of black women – across the centuries: from the days of slavery to Jack the Ripper to police custody a few years ago. There are so many ways to die:

really nearly took that other plane on 9/11

had a coconut fall on your head

saw your village being bombed

slipped taking a selfie by the Grand Canyon

had a fight with an alligator

got stranded in a fierce and fast-moving bushfire

Speaking of fire, and of the title, Wolf (biracial, nonbinary, and possibly bipolar) is here to narrate only because Mrs Death missed one. Their mum died in a house fire. Wolf should have died that day, too, but heard a voice saying “Wake up, Wolf … Can you smell smoke?” Were they spared deliberately, or did Mrs Death make a mistake? (After all, we learn that when a patient briefly wakes up on the operating table before dying for good, it’s because Mrs Death’s printer got jammed.)

Where I think the novel really succeeds is in balancing its two levels: the cosmic, in which Life and Death are sisters and Time is Death’s lover in a sort of creation myth; and the personal, in which Wolf’s family tree, printed at the end, is an appalling litany of accidental deaths and executions. It’s easy to see why Wolf is so traumatized, but Mrs Death, ironically, reminds him that, despite all of the world’s fallen heroes and ongoing crises, there is still such beauty to be found in life.

All the warmth and all the joy is boiled in a soup of memory, we stir the good stuff from the bottom of the pot and hold the ladle up, drink, we say, look at all the good chunks of goodness, take in your share of good times, good music, good books, good food, good laughter, good people, be grateful for the good stuff, life and death, we say, drink.

There were a few spots where I thought the content repetitive and wondered if the miscellany format distracted from the narrative, but overall the book more than lives up to its fantastic cover, title, and premise. And with the pandemic’s global death toll rising daily, it could hardly be more relevant.

Unusual, musical, and a real pleasure to read: this is the first entry on my Best of 2021 shelf.

With thanks to Canongate for the free copy for review.

Tomorrow I’ll review a few more of January’s fiction releases, followed by nonfiction on Saturday.

My simple reading goals for 2021 were to read more biographies, classics, doorstoppers and travel books – genres that tend to sit on my shelves unread. I read one biography in graphic novel form (Orwell by Pierre Christin), but otherwise didn’t manage any. I only read three doorstoppers the whole year, but 29 classics – defining them is always a nebulous matter, but I’m going with books from before 1980 – a number I’m happy with.

My simple reading goals for 2021 were to read more biographies, classics, doorstoppers and travel books – genres that tend to sit on my shelves unread. I read one biography in graphic novel form (Orwell by Pierre Christin), but otherwise didn’t manage any. I only read three doorstoppers the whole year, but 29 classics – defining them is always a nebulous matter, but I’m going with books from before 1980 – a number I’m happy with. Surprisingly, I did the best with travel books, perhaps because I’ve started thinking about travel writing more broadly and not just as a white man going to the other side of the world and seeing exotic things, since I don’t often enjoy such narratives. Granted, I did read a few like that, and they were exceptional (The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński and Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth), but if I include essays, memoirs and poetry with significant place-based and migration themes, I was at 26.

Surprisingly, I did the best with travel books, perhaps because I’ve started thinking about travel writing more broadly and not just as a white man going to the other side of the world and seeing exotic things, since I don’t often enjoy such narratives. Granted, I did read a few like that, and they were exceptional (The Glitter in the Green by Jon Dunn, The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński and Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth), but if I include essays, memoirs and poetry with significant place-based and migration themes, I was at 26.

A 2021 book that everyone loved but me: The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles.

A 2021 book that everyone loved but me: The Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles.

A Still Life by Josie George: Over a year of lockdowns, many of us became accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (Reviewed for TLS.)

A Still Life by Josie George: Over a year of lockdowns, many of us became accustomed to spending most of the time at home. But for Josie George, social isolation is nothing new. Chronic illness long ago reduced her territory to her home and garden. The magic of A Still Life is in how she finds joy and purpose despite extreme limitations. Opening on New Year’s Day and travelling from one winter to the next, the book is a window onto George’s quiet existence as well as the turning of the seasons. (Reviewed for TLS.)

A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller: Miller, a professor of creative writing, delivers a master class on the composition and appreciation of autobiographical essays. In 18 concise pieces, she tracks her development as a writer and discusses the “lyric essay”—a form as old as Seneca that prioritizes imagery over narrative. These innovative and introspective essays, ideal for fans of Anne Fadiman, showcase the interplay of structure and content. (Coming out on July 13th from the University of Michigan Press. My first review for Shelf Awareness.)

A Braided Heart by Brenda Miller: Miller, a professor of creative writing, delivers a master class on the composition and appreciation of autobiographical essays. In 18 concise pieces, she tracks her development as a writer and discusses the “lyric essay”—a form as old as Seneca that prioritizes imagery over narrative. These innovative and introspective essays, ideal for fans of Anne Fadiman, showcase the interplay of structure and content. (Coming out on July 13th from the University of Michigan Press. My first review for Shelf Awareness.)

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download]

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin [Jan. 21, Hodder & Stoughton / Jan. 12, Putnam] “Cinderella married the man of her dreams – the perfect ending she deserved after diligently following all the fairy-tale rules. Yet now, two children and thirteen-and-a-half years later, things have gone badly wrong. One night, she sneaks out of the palace to get help from the Witch who, for a price, offers love potions to disgruntled housewives.” A feminist retelling. I loved Grushin’s previous novel, Forty Rooms. [Edelweiss download] The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of

The Prophets by Robert Jones Jr. [Jan. 21, Quercus / Jan. 5, G.P. Putnam’s Sons] “A singular and stunning debut novel about the forbidden union between two enslaved young men on a Deep South plantation, the refuge they find in each other, and a betrayal that threatens their existence.” Lots of hype about this one. I’m getting Days Without End vibes, and the mention of copious biblical references is a draw for me rather than a turn-off. The cover looks so much like the UK cover of  A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson [Feb. 18, Chatto & Windus / Feb. 16, Knopf Canada] “It’s North Ontario in 1972, and seven-year-old Clara’s teenage sister Rose has just run away from home. At the same time, a strange man – Liam – drives up to the house next door, which he has just inherited from Mrs Orchard, a kindly old woman who was friendly to Clara … A beautiful portrait of a small town, a little girl and an exploration of childhood.” I’ve loved the two Lawson novels I’ve read. [Publisher request pending]

A Town Called Solace by Mary Lawson [Feb. 18, Chatto & Windus / Feb. 16, Knopf Canada] “It’s North Ontario in 1972, and seven-year-old Clara’s teenage sister Rose has just run away from home. At the same time, a strange man – Liam – drives up to the house next door, which he has just inherited from Mrs Orchard, a kindly old woman who was friendly to Clara … A beautiful portrait of a small town, a little girl and an exploration of childhood.” I’ve loved the two Lawson novels I’ve read. [Publisher request pending] Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March.

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro [March 2, Faber & Faber / Knopf] Synopsis from Faber e-mail: “Klara and the Sun is the story of an ‘Artificial Friend’ who … is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. A luminous narrative about humanity, hope and the human heart.” I’m not an Ishiguro fan per se, but this looks set to be one of the biggest books of the year. I’m tempted to pre-order a signed copy as part of an early bird ticket to a Faber Members live-streamed event with him in early March. Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to

Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley [March 18, Hodder & Stoughton / April 20, Algonquin Books] “The Soho that Precious and Tabitha live and work in is barely recognizable anymore. … Billionaire-owner Agatha wants to kick the women out to build expensive restaurants and luxury flats. Men like Robert, who visit the brothel, will have to go elsewhere. … An insightful and ambitious novel about property, ownership, wealth and inheritance.” This sounds very different to  Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download]

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge [March 30, Algonquin Books; April 29, Serpent’s Tail] “Coming of age as a free-born Black girl in Reconstruction-era Brooklyn, Libertie Sampson” is expected to follow in her mother’s footsteps as a doctor. “When a young man from Haiti proposes, she accepts, only to discover that she is still subordinate to him and all men. … Inspired by the life of one of the first Black female doctors in the United States.” I loved Greenidge’s underappreciated debut, We Love You, Charlie Freeman. [Edelweiss download] An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.”

An Ordinary Wonder by Buki Papillon [April 9, Dialogue Books] “Richly imagined with art, proverbs and folk tales, this moving and modern novel follows Oto through life at home and at boarding school in Nigeria, through the heartbreak of living as a boy despite their profound belief they are a girl, and through a hunger for freedom that only a new life in the United States can offer. … a powerful coming-of-age story that explores complex desires as well as challenges of family, identity, gender and culture, and what it means to feel whole.” Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead [May 4, Doubleday / Knopf] “In 1940s London, after a series of reckless romances and a spell flying to aid the war effort, Marian embarks on a treacherous, epic flight in search of the freedom she has always craved. She is never seen again. More than half a century later, Hadley Baxter, a troubled Hollywood starlet beset by scandal, is irresistibly drawn to play Marian Graves in her biopic.” I loved Seating Arrangements and have been waiting for a new Shipstead novel for seven years!

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead [May 4, Doubleday / Knopf] “In 1940s London, after a series of reckless romances and a spell flying to aid the war effort, Marian embarks on a treacherous, epic flight in search of the freedom she has always craved. She is never seen again. More than half a century later, Hadley Baxter, a troubled Hollywood starlet beset by scandal, is irresistibly drawn to play Marian Graves in her biopic.” I loved Seating Arrangements and have been waiting for a new Shipstead novel for seven years! The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner.

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico [May 6, Faber & Faber; this has been out since May 2020 in the USA, but was pushed back a year in the UK] “Linda returns to Colombia after 20 years away. Sent to England after her mother’s death when she was eight, she’s searching for the person who can tell her what’s happened in the time that has passed. Matty – Lina’s childhood confidant, her best friend – now runs a refuge called The Anthill for the street kids of Medellín.” Pachico was our Young Writer of the Year shadow panel winner. Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,

Filthy Animals: Stories by Brandon Taylor [June 24, Daunt Books / June 21, Riverhead] “In the series of linked stories at the heart of Filthy Animals, set among young creatives in the American Midwest, a young man treads delicate emotional waters as he navigates a series of sexually fraught encounters with two dancers in an open relationship, forcing him to weigh his vulnerabilities against his loneliness.” Sounds like the perfect follow-up for those of us who loved his Booker-shortlisted debut novel,  Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending]

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape by Cal Flyn [Jan. 21, William Collins; June 1, Viking] “A variety of wildlife not seen in many lifetimes has rebounded on the irradiated grounds of Chernobyl. A lush forest supports thousands of species that are extinct or endangered everywhere else on earth in the Korean peninsula’s narrow DMZ. … Islands of Abandonment is a tour through these new ecosystems … ultimately a story of redemption”. Good news about nature is always nice to find. [Publisher request pending] The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued!

The Believer by Sarah Krasnostein [March 2, Text Publishing – might be Australia only; I’ll have an eagle eye out for news of a UK release] “This book is about ghosts and gods and flying saucers; certainty in the absence of knowledge; how the stories we tell ourselves to deal with the distance between the world as it is and as we’d like it to be can stunt us or save us.” Krasnostein was our Wellcome Book Prize shadow panel winner in 2019. She told us a bit about this work in progress at the prize ceremony and I was intrigued! A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise.

A History of Scars: A Memoir by Laura Lee [March 2, Atria Books; no sign of a UK release] “In this stunning debut, Laura Lee weaves unforgettable and eye-opening essays on a variety of taboo topics. … Through the vivid imagery of mountain climbing, cooking, studying writing, and growing up Korean American, Lee explores the legacy of trauma on a young queer child of immigrants as she reconciles the disparate pieces of existence that make her whole.” I was drawn to this one by Roxane Gay’s high praise. Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of

Everybody: A Book about Freedom by Olivia Laing [April 29, Picador / May 4, W. W. Norton & Co.] “The body is a source of pleasure and of pain, at once hopelessly vulnerable and radiant with power. … Laing charts an electrifying course through the long struggle for bodily freedom, using the life of the renegade psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich to explore gay rights and sexual liberation, feminism, and the civil rights movement.” Wellcome Prize fodder from the author of  Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.

Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt [May 4, Little, Brown Spark; no sign of a UK release] “Cutting-edge science supports a truth that poets, artists, mystics, and earth-based cultures across the world have proclaimed over millennia: life on this planet is radically interconnected. … In the tradition of Rachel Carson, Elizabeth Kolbert, and Mary Oliver, Haupt writes with urgency and grace, reminding us that at the crossroads of science, nature, and spirit we find true hope.” I’m a Haupt fan.