Six Degrees of Separation: From Wintering to The Summer of the Bear

This month we begin with Wintering by Katherine May. I reviewed this for the Times Literary Supplement back in early 2020 and enjoyed the blend of memoir, nature and travel writing. (See also Kate’s opening post.)

#1 May travels to Iceland, which is the location of Sarah Moss’s memoir Names for the Sea. I’ve read nine of Moss’s books and consider her one of my favourite contemporary authors. (I’m currently rereading Night Waking.)

#1 May travels to Iceland, which is the location of Sarah Moss’s memoir Names for the Sea. I’ve read nine of Moss’s books and consider her one of my favourite contemporary authors. (I’m currently rereading Night Waking.)

#2 Nancy Campbell’s Fifty Words for Snow shares an interest in languages and naming. I noted that the Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” refers to snowflakes as large as a dog’s paw.

#2 Nancy Campbell’s Fifty Words for Snow shares an interest in languages and naming. I noted that the Icelandic “hundslappadrifa” refers to snowflakes as large as a dog’s paw.

#3 In 2018–19, Campbell was the poet laureate for the Canal & River Trust. As part of her tour of the country’s waterways, she came to Newbury and wrote a poem on commission about the community gardening project I volunteer with. (Here’s her blog post about the experience.) Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson is about a canalboat journey.

#3 In 2018–19, Campbell was the poet laureate for the Canal & River Trust. As part of her tour of the country’s waterways, she came to Newbury and wrote a poem on commission about the community gardening project I volunteer with. (Here’s her blog post about the experience.) Three Women and a Boat by Anne Youngson is about a canalboat journey.

#4 Youngson’s novel was inspired by the setup of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Another book loosely based on a classic is The Decameron Project, a set of 29 short stories ranging from realist to dystopian in their response to pandemic times.

#4 Youngson’s novel was inspired by the setup of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. Another book loosely based on a classic is The Decameron Project, a set of 29 short stories ranging from realist to dystopian in their response to pandemic times.

#5 Another project updating the classics was the Hogarth Shakespeare series. One of these books (though not my favourite) was The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson, her take on The Winter’s Tale.

#5 Another project updating the classics was the Hogarth Shakespeare series. One of these books (though not my favourite) was The Gap of Time by Jeanette Winterson, her take on The Winter’s Tale.

#6 Even if you’ve not read it (it happened to be on my undergraduate curriculum), you probably know that The Winter’s Tale famously includes the stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear.” I’m finishing with The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, one of the novels I read on my trip to the Outer Hebrides because it’s set on North Uist. I’ll review it in full soon, but for now will say that it does actually have a bear in it, and is based on a true story.

#6 Even if you’ve not read it (it happened to be on my undergraduate curriculum), you probably know that The Winter’s Tale famously includes the stage direction “Exit, pursued by a bear.” I’m finishing with The Summer of the Bear by Bella Pollen, one of the novels I read on my trip to the Outer Hebrides because it’s set on North Uist. I’ll review it in full soon, but for now will say that it does actually have a bear in it, and is based on a true story.

I’m pleased with myself for going from Wintering (via various other ice, snow and winter references) to a “Summer” title. We’ve crossed the hemispheres from Kate’s Australian winter to summertime here.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.) Next month’s starting point will be the recent winner of the Women’s Prize, The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki.

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Women’s Prize 2022: Longlist Wishes vs. Predictions

Next Tuesday the 8th, the 2022 Women’s Prize longlist will be announced.

First I have a list of 16 novels I want to be longlisted, because I’ve read and loved them (or at least thought they were interesting), or am currently reading and enjoying them, or plan to read them soon, or am desperate to get hold of them.

Wishlist

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield (my review)

Ghosted by Jenn Ashworth (my review)

These Days by Lucy Caldwell

Damnation Spring by Ash Davidson – currently reading

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González – currently reading

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall (my review)

Early Morning Riser by Katherine Heiny (my review)

Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

My Monticello by Jocelyn Nicole Johnson (my review)

Devotion by Hannah Kent – currently reading

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith – currently reading

When the Stars Go Dark by Paula McLain (my review)

The Swimmers by Julie Otsuka – review coming to Shiny New Books on Thursday

Brood by Jackie Polzin (my review)

The Performance by Claire Thomas (my review)

Then I have a list of 16 novels I think will be longlisted mostly because of the buzz around them, or they’re the kind of thing the Prize always recognizes (like danged GREEK MYTHS), or they’re authors who have been nominated before – previous shortlistees get a free pass when it comes to publisher submissions, you see – or they’re books I might read but haven’t gotten to yet.

Predictions

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Second Place by Rachel Cusk (my review)

Matrix by Lauren Groff

Free Love by Tessa Hadley

The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris (my review)

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

The Fell by Sarah Moss (my review)

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney (my review)

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

Still Life by Sarah Winman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara – currently reading

*A wildcard entry that could fit on either list: Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason (my review).*

Okay, no more indecision and laziness. Time to combine these two into a master list that reflects my taste but also what the judges of this prize generally seem to be looking for. It’s been a year of BIG books – seven of these are over 400 pages; three of them over 600 pages even – and a lot of historical fiction, but also some super-contemporary stuff. Seven BIPOC authors as well, which would be an improvement over last year’s five and closer to the eight from two years prior. A caveat: I haven’t given thought to publisher quotas here.

MY WOMEN’S PRIZE FORECAST

Love Marriage by Monica Ali

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo

Olga Dies Dreaming by Xóchitl González

Matrix by Lauren Groff

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Devotion by Hannah Kent

Build Your House Around My Body by Violet Kupersmith

The Fell by Sarah Moss

My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley

Beautiful World, Where Are You by Sally Rooney

Ariadne by Jennifer Saint

The Island of Missing Trees by Elif Shafak

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead

Pandora by Susan Stokes-Chapman

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara

What do you think?

See also Laura’s, Naty’s, and Rachel’s predictions (my final list overlaps with theirs on 10, 5 and 8 titles, respectively) and Susan’s wishes.

Just to further overwhelm you, here are the other 62 eligible 2021–22 novels that were on my radar but didn’t make the cut:

In Every Mirror She’s Black by Lola Akinmade Åkerström

Violeta by Isabel Allende

The Leviathan by Rosie Andrews

Somebody Loves You by Mona Arshi

The Stars Are Not Yet Bells by Hannah Lillith Assadi

The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore

Mary Jane by Jessica Anya Blau

Defenestrate by Renee Branum

Songs in Ursa Major by Emma Brodie

Assembly by Natasha Brown

We Were Young by Niamh Campbell

The Raptures by Jan Carson

A Very Nice Girl by Imogen Crimp

Scary Monsters by Michelle de Kretser

Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline

Infinite Country by Patricia Engel

Love & Saffron by Kim Fay

Mrs March by Virginia Feito

Booth by Karen Joy Fowler

Tides by Sara Freeman

I Couldn’t Love You More by Esther Freud

Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia

Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge

Listening Still by Anne Griffin

The Twyford Code by Janice Hallett

Mrs England by Stacey Halls

Three Rooms by Jo Hamya

The Giant Dark by Sarvat Hasin

The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller

Violets by Alex Hyde

Fault Lines by Emily Itami

Beasts of a Little Land by Juhea Kim

Woman, Eating by Claire Kohda

Notes on an Execution by Danya Kukafka

Paul by Daisy Lafarge

Circus of Wonders by Elizabeth Macneal

The Truth About Her by Jacqueline Maley

Wahala by Nikki May

Once There Were Wolves by Charlotte McConaghy

Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors

The Exhibitionist by Charlotte Mendelson

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki

The Anthill by Julianne Pachico

The Vixen by Francine Prose

The Five Wounds by Kirstin Valdez Quade

Malibu Rising by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Cut Out by Michèle Roberts

This One Sky Day by Leone Ross

Secrets of Happiness by Joan Silber

Cold Sun by Anita Sivakumaran

Hear No Evil by Sarah Smith

Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

Animal by Lisa Taddeo

Daughter of the Moon Goddess by Sue Lynn Tan

Lily by Rose Tremain

French Braid by Anne Tyler

We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida

I Love You but I’ve Chosen Darkness by Claire Vaye Watkins

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

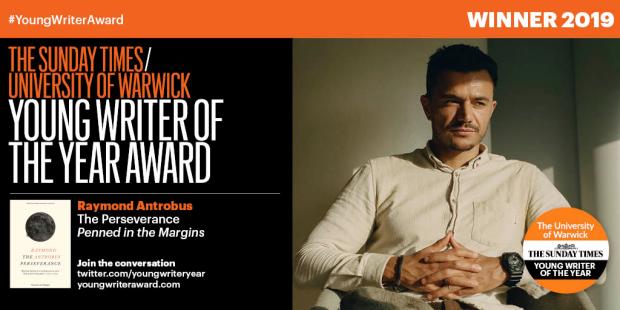

Young Writer of the Year Award 2021 Shortlist: Reactions and Prediction

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award was a bookish highlight of 2017 for me and, looking back, still one of the best things I’ve achieved in my time as a book blogger. Each year I eagerly keep an eye out for the award shortlist to see how many I’ve read and who I think the judges will choose as the winner. The prize has a higher profile and cash fund this year thanks to new sponsorship from the Charlotte Aitken Trust and partnership with Waterstones.

Last May I started a list of books and authors I expected would be eligible, and continued updating it throughout the year. I was certainly expecting Open Water to make the cut, but I had a lot of other wishes that didn’t come true, particularly Charlie Gilmour for Featherhood, Daisy Johnson for Sisters, Will McPhail for In, Merlin Sheldrake for Entangled Life, and Eley Williams for The Liar’s Dictionary.

Yesterday the five nominees – three debut novels, one work of nonfiction, and one poetry collection – were announced in the Sunday Times and on the website. I happen to have already read three of them. I was vaguely interested in Megan Nolan’s novel already so will get it out from the library to read soon; I had not heard of Anna Beecher’s at all but would be willing to read a review copy if one came my way.

Here Comes the Miracle by Anna Beecher: Sounds potentially mawkish in a Jodi Picoult or Sarah Winman way. Publisher’s blurb: “It begins with a miracle: a baby born too small and too early, but defiantly alive. This is Joe. Decades before, another miracle. In a patch of nettle-infested wilderness, a seventeen-year-old boy falls in love with his best friend, Jack. This is Edward. Joe gains a sister, Emily. From the outset, her life is framed by his. She watches him grow into a young man who plays the violin magnificently and longs for a boyfriend. A young man who is ready to begin. Edward, after being separated from Jack, builds a life with Eleanor. They start a family and he finds himself a grandfather to Joe and Emily. When Joe is diagnosed with stage 4 cancer, Emily and the rest of the family are left waiting for a miracle.”

Here Comes the Miracle by Anna Beecher: Sounds potentially mawkish in a Jodi Picoult or Sarah Winman way. Publisher’s blurb: “It begins with a miracle: a baby born too small and too early, but defiantly alive. This is Joe. Decades before, another miracle. In a patch of nettle-infested wilderness, a seventeen-year-old boy falls in love with his best friend, Jack. This is Edward. Joe gains a sister, Emily. From the outset, her life is framed by his. She watches him grow into a young man who plays the violin magnificently and longs for a boyfriend. A young man who is ready to begin. Edward, after being separated from Jack, builds a life with Eleanor. They start a family and he finds himself a grandfather to Joe and Emily. When Joe is diagnosed with stage 4 cancer, Emily and the rest of the family are left waiting for a miracle.”

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: One of my top nonfiction books of 2021, but I’ll confess I hadn’t realized Flyn was eligible. (Now that I’m, ahem, a few years past the cutoff age myself, I can find it difficult to gauge the difference between early 30s and late 30s in appearance.) Flyn travels to neglected and derelict places, looking for the traces of human impact and noting how landscapes restore themselves – how life goes on without us. Places like a wasteland where there was once mining, nuclear exclusion zones, the depopulated city of Detroit, and areas that have been altered by natural disasters and conflict. The writing is literary and evocative, at times reminiscent of Peter Matthiessen’s. It’s a nature/travel book with a difference, and the poetic eye helps you to see things anew.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flyn: One of my top nonfiction books of 2021, but I’ll confess I hadn’t realized Flyn was eligible. (Now that I’m, ahem, a few years past the cutoff age myself, I can find it difficult to gauge the difference between early 30s and late 30s in appearance.) Flyn travels to neglected and derelict places, looking for the traces of human impact and noting how landscapes restore themselves – how life goes on without us. Places like a wasteland where there was once mining, nuclear exclusion zones, the depopulated city of Detroit, and areas that have been altered by natural disasters and conflict. The writing is literary and evocative, at times reminiscent of Peter Matthiessen’s. It’s a nature/travel book with a difference, and the poetic eye helps you to see things anew.

My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long: I read this when it was shortlisted for last year’s Costa Awards and reviewed it when it was shortlisted for the Folio Prize. It’s had a lot of critical attention now, but wasn’t my cup of tea. Race, sex, and religion come into play, but the focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long: I read this when it was shortlisted for last year’s Costa Awards and reviewed it when it was shortlisted for the Folio Prize. It’s had a lot of critical attention now, but wasn’t my cup of tea. Race, sex, and religion come into play, but the focus is on memories of coming of age, with the voice sometimes a girl’s and sometimes a grown woman’s. Her course veers between innocence and hazard. She must make her way beyond the world’s either/or distinctions and figure out how to be multiple people at once (biracial, bisexual). Her Black mother is a forceful presence; “Red Hoover” is a funny account of trying to date a Nigerian man to please her mother. Much of the rest of the book failed to click with me, but the experience of poetry is so subjective that I find it hard to give any specific reasons why that’s the case.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson: I always enjoy the use of second person narration. It works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles. Ultimately, I wasn’t convinced that fiction was the right vehicle for this story, especially with all the references to other authors, from Hanif Abdurraqib to Zadie Smith (NW, in particular); I think a memoir with cultural criticism was what Nelson really intended. I’ll keep an eye out for him, though – with his next book he might truly find his voice.

Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson: I always enjoy the use of second person narration. It works pretty well in this love story between two young Black British people in South London. The title is a metaphor for the possibilities and fear of intimacy. The protagonist, a photographer, doesn’t know what to do with his anger about how young Black men are treated. I felt Nelson was a little heavy-handed in his treatment of this theme, though I did love that the pivotal scene is set in a barbershop, a place where men reveal more of themselves than usual – I was reminded of a terrific play I saw a few years ago, Barber Shop Chronicles. Ultimately, I wasn’t convinced that fiction was the right vehicle for this story, especially with all the references to other authors, from Hanif Abdurraqib to Zadie Smith (NW, in particular); I think a memoir with cultural criticism was what Nelson really intended. I’ll keep an eye out for him, though – with his next book he might truly find his voice.

Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan: Another debut from an Irish writer – heir to Sally Rooney? Publisher’s blurb: “In the first scene of this provocative gut-punch of a novel, our unnamed narrator meets a magnetic writer named Ciaran and falls, against her better judgment, completely in his power. After a brief, all-consuming romance he abruptly rejects her, sending her into a tailspin of jealous obsession and longing. … Part breathless confession, part lucid critique, Acts of Desperation renders a consciousness split between rebellion and submission, between escaping degradation and eroticizing it, between loving and being lovable. With unsettling, electric precision, Nolan dissects one of life’s most elusive mysteries: Why do we want what we want, and how do we want it?”

Acts of Desperation by Megan Nolan: Another debut from an Irish writer – heir to Sally Rooney? Publisher’s blurb: “In the first scene of this provocative gut-punch of a novel, our unnamed narrator meets a magnetic writer named Ciaran and falls, against her better judgment, completely in his power. After a brief, all-consuming romance he abruptly rejects her, sending her into a tailspin of jealous obsession and longing. … Part breathless confession, part lucid critique, Acts of Desperation renders a consciousness split between rebellion and submission, between escaping degradation and eroticizing it, between loving and being lovable. With unsettling, electric precision, Nolan dissects one of life’s most elusive mysteries: Why do we want what we want, and how do we want it?”

You can read more about these books and the judges’ reactions to them on the website. This year’s judges are authors Tahmima Anam, Sarah Moss, and Andrew O’Hagan; critic Claire Lowdon; and creative writing teacher Gonzalo C. Garcia. The chair, as always, is Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate.

Reasoning and Prediction

- Poetry has won the last two years in a row.

- Nelson has just won the Costa First Novel Award (though the judges chose Raymond Antrobus, at that time already a recipient of multiple major awards).

- We haven’t had a female winner since 2017, so it’s past time.

- We haven’t had a nonfiction winner since Adam Weymouth in 2018 for Kings of the Yukon.

So, I’d love for Cal Flyn to win for the excellent and timely Islands of Abandonment. She’s had a few nominations (the Baillie Gifford Prize, the Saltire Award, the Wainwright Prize) but not won anything, and richly deserves to.

I haven’t heard yet if there will be a shadow panel this year. Anyone got any intel on this? If it goes ahead in person this year, I’ll hope to attend the awards ceremony in London on 24 February. In any case, I’ll be looking out for the winner announcement.

Have you read anything from this year’s shortlist?

Novellas in November Wrap-Up

Last year, our first of hosting Novellas in November as an official blogger challenge, we had 89 posts by 30 bloggers. This year, Cathy and I have been simply blown away by the level of participation: as of this afternoon, our count is that 49 bloggers have taken part, publishing just over 200 posts and covering over 270 books. We’ve done our best to keep up with the posts, which we’ve each been collecting as links on the opening master post. (Here’s mine.)

Thank you all for being so engaged with #NovNov, including with the buddy reads we tried out for the first time this year. We’re already thinking about changes we might implement for next year.

A special mention goes to Simon of Stuck in a Book for being such a star supporter and managing to review a novella on most days of the month.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Our most reviewed books of the month included new releases (The Fell by Sarah Moss, Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan, Assembly by Natasha Brown, and The Writer’s Cats by Muriel Barbery), our four buddy reads, and The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy.

Some authors who were reviewed more than once (highlighting different works) were Margaret Atwood, Henry James, Elizabeth Jolley, Amos Oz, George Simenon, and Muriel Spark.

Of course, novellas are great to read the whole year round and not just in November, but we hope this has been a good excuse to pick up some short books and appreciate how much can be achieved with such a limited number of pages. If we missed any of your coverage, let us know and we will gladly add it in to the master list.

See you next year!

The Fell by Sarah Moss for #NovNov

Sarah Moss’s latest three releases have all been of novella length. I reviewed Ghost Wall for Novellas in November in 2018, and Summerwater in August 2020. In this trio, she’s demonstrated a fascination with what happens when people of diverging backgrounds and opinions are thrown together in extreme circumstances. Moss almost stops time as her effortless third-person omniscient narration moves from one character’s head to another. We feel that we know each one’s experiences and motivations from the inside. Whereas Ghost Wall was set in two weeks of a late-1980s summer, Summerwater and now the taut The Fell have pushed that time compression even further, spanning a day and about half a day, respectively.

A circadian narrative holds a lot of appeal – we’re all tantalized, I think, by the potential difference that one day can make. The particular day chosen as the backdrop for The Fell offers an ideal combination of the mundane and the climactic because it was during the UK’s November 2020 lockdown. On top of that blanket restriction, single mum Kate has been exposed to Covid-19 via a café colleague, so she and her teenage son Matt are meant to be in strict two-week quarantine. Except Kate can’t bear to be cooped up one minute longer and, as dusk falls, she sneaks out of their home in the Peak District National Park to climb a nearby hill. She knows this fell like the back of her hand, so doesn’t bother taking her phone.

Over the next 12 hours or so, we dart between four stream-of-consciousness internal monologues: besides Kate and Matt, the two main characters are their neighbour, Alice, an older widow who has undergone cancer treatment; and Rob, part of the volunteer hill rescue crew sent out to find Kate when she fails to return quickly. For the most part – as befits the lockdown – each is stuck in their solitary musings (Kate regrets her marriage, Alice reflects on a bristly relationship with her daughter, Rob remembers a friend who died up a mountain), but there are also a few brief interactions between them. I particularly enjoyed time spent with Kate as she sings religious songs and imagines a raven conducting her inquisition.

What Moss wants to do here, is done well. My misgiving is to do with the recycling of an identical approach from Summerwater – not just the circadian limit, present tense, no speech marks and POV-hopping, but also naming each short chapter after a random phrase from it. Another problem is one of timing. Had this come out last November, or even this January, it might have been close enough to events to be essential. Instead, it seems stuck in a time warp. Early on in the first lockdown, when our local arts venue’s open mic nights had gone online, one participant made a semi-professional music video for a song with the refrain “everyone’s got the same jokes.”

That’s how I reacted to The Fell: baking bread and biscuits, a family catch-up on Zoom, repainting and clearouts, even obsessive hand-washing … the references were worn out well before a draft was finished. Ironic though it may seem, I feel like I’ve found more cogent commentary about our present moment from Moss’s historical work. Yet I’ve read all of her fiction and would still list her among my favourite contemporary writers. Aspiring creative writers could approach the Summerwater/The Fell duology as a masterclass in perspective, voice and concise plotting. But I hope for something new from her next book.

[180 pages]

With thanks to Picador for the free copy for review.

Other reviews:

Young Writer of the Year Award Ceremony

It was great to be back at the London Library for last night’s Young Writer of the Year Award prize-giving ceremony. I got to meet Anne Cater (Random Things through my Letterbox) from the shadow panel, who’s coordinated a few blog tours I’ve participated in, as well as Ova Ceren (Excuse My Reading). It was also good to see shadow panelist Linda (Linda’s Book Bag) again and hang out with Clare (A Little Blog of Books), also on the shadow panel in my year, and Eric (Lonesome Reader), who seems to get around to every London literary event.

In case you haven’t heard, the shadow panel chose Salt Slow by Julia Armfield as their very deserving winner, but the official winner was Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance. In all honesty, I’d given no thought to the possibility of it winning, mostly because Antrobus has already won several major prizes for the book, including this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize (I reviewed it for the Prize’s blog tour). Now, there’s no rule saying you can’t win multiple prizes for the same book, but what struck me strangely about this case is that Kate Clanchy was a judge for both the Folio Prize and the Young Writer Award.

In case you haven’t heard, the shadow panel chose Salt Slow by Julia Armfield as their very deserving winner, but the official winner was Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance. In all honesty, I’d given no thought to the possibility of it winning, mostly because Antrobus has already won several major prizes for the book, including this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize (I reviewed it for the Prize’s blog tour). Now, there’s no rule saying you can’t win multiple prizes for the same book, but what struck me strangely about this case is that Kate Clanchy was a judge for both the Folio Prize and the Young Writer Award.

Antrobus seemed genuinely taken aback by his win and gave a very gracious speech in which he said that he looked forward to all the shortlistees contributing to the canon of English literature. He was quickly whisked away for a photo shoot, so I didn’t get a chance to congratulate him or have my book signed, but I did get to meet Julia Armfield and Yara Rodrigues Fowler and get their autographs.

Some interesting statistics for you: in three of the past four years the shadow panel has chosen a short story collection as its winner (and they say no one likes short stories these days!). In none of those four years did the shadow panel correctly predict the official winner – so, gosh, is it the kiss of death to be the shadow panel winner?!

In the official press release, chair of judges and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes that The Perseverance is “both very personal and immensely resonant. The result is a memoir in verse very, very affecting and fresh.” Poet Kate Clanchy adds, “we wanted to find a writer who both speaks for now and who we were confident would continue to produce valuable, central work. … it was the humanity of the book, its tempered kindness, and the commitment not just to recognising difference but to the difficult act of forgiveness that made us confident we had found a winner for this extraordinary year.”

In the official press release, chair of judges and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes that The Perseverance is “both very personal and immensely resonant. The result is a memoir in verse very, very affecting and fresh.” Poet Kate Clanchy adds, “we wanted to find a writer who both speaks for now and who we were confident would continue to produce valuable, central work. … it was the humanity of the book, its tempered kindness, and the commitment not just to recognising difference but to the difficult act of forgiveness that made us confident we had found a winner for this extraordinary year.”

Also present at the ceremony were Sarah Moss (who teaches at the University of Warwick, the Award’s new co-sponsor) and Katya Taylor. I could have sworn I spotted Deborah Levy, too, but after conferring with other book bloggers we decided it was just someone who looked a lot like her.

In any event, it was lovely to see London all lit up with Christmas lights and to spend a couple of hours celebrating up-and-coming writing talent. (And I just managed to catch the last train home and avoid a rail replacement bus nightmare.)

Looking forward to next year already!

A sweltering summer versus an encasing of ice; an ordinary day versus decades of futile waiting. Sackville explores these contradictions only to deflate them, collapsing time such that a polar explorer’s wife and her great-great-niece can inhabit the same literal and emotional space despite being separated by more than a century. When Edward Mackley went off on his expedition in the early 1900s, he left behind Emily, his devoted, hopeful new bride. She was to live out the rest of her days in the Mackley family home with her brother-in-law and his growing family; Edward never returned. Now Julia and her husband Simon reside in that same Victorian house, serving as custodians of memories and artifacts from her ancestors’ travels and naturalist observations. From one early morning until the next, we peer into this average marriage with its sadness and silences. On this day, Julia discovers a family secret, and late on reveals another of her own, that subtly change how we see her and Emily.

A sweltering summer versus an encasing of ice; an ordinary day versus decades of futile waiting. Sackville explores these contradictions only to deflate them, collapsing time such that a polar explorer’s wife and her great-great-niece can inhabit the same literal and emotional space despite being separated by more than a century. When Edward Mackley went off on his expedition in the early 1900s, he left behind Emily, his devoted, hopeful new bride. She was to live out the rest of her days in the Mackley family home with her brother-in-law and his growing family; Edward never returned. Now Julia and her husband Simon reside in that same Victorian house, serving as custodians of memories and artifacts from her ancestors’ travels and naturalist observations. From one early morning until the next, we peer into this average marriage with its sadness and silences. On this day, Julia discovers a family secret, and late on reveals another of her own, that subtly change how we see her and Emily. “The literature of nineteenth-century arctic exploration is full of coincidence and drama—last-minute rescues, a desperate rifle shot to secure food for starving men, secret letters written to painfully missed loved ones. There are moments of surreal stillness, as in Parry’s journal when he writes of the sound of the human voice in the land. And of tender ministration and quiet forbearance in the face of inevitable death.”

“The literature of nineteenth-century arctic exploration is full of coincidence and drama—last-minute rescues, a desperate rifle shot to secure food for starving men, secret letters written to painfully missed loved ones. There are moments of surreal stillness, as in Parry’s journal when he writes of the sound of the human voice in the land. And of tender ministration and quiet forbearance in the face of inevitable death.” In 2011 Rapp’s baby son Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a degenerative nerve condition that causes blindness, deafness, seizures, paralysis and, ultimately, death. Tay-Sachs is usually seen in Ashkenazi Jews, so it came as a surprise: Rapp and her husband Rick both had to be carriers, whereas only he was Jewish; they never thought to get tested.

In 2011 Rapp’s baby son Ronan was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, a degenerative nerve condition that causes blindness, deafness, seizures, paralysis and, ultimately, death. Tay-Sachs is usually seen in Ashkenazi Jews, so it came as a surprise: Rapp and her husband Rick both had to be carriers, whereas only he was Jewish; they never thought to get tested. Things got worse before they got better. As is common for couples who lose a child, Rapp and her first husband separated, soon after she completed her book. In the six months leading up to Ronan’s death in February 2013, his condition deteriorated rapidly and he needed hospice caretakers. Rapp came close to suicide. But in those desperate months, she also threw herself into a new relationship with Kent, a 20-years-older man who was there for her as Ronan was dying and would become her second husband and the father of her daughter, Charlotte (“Charlie”). The acrimonious split from Rick and the astonishment of a new life with Kent – starting in the literal sanctuary of his converted New Mexico chapel, and then moving to California – were two sides of a coin. So were missing Ronan and loving Charlie.

Things got worse before they got better. As is common for couples who lose a child, Rapp and her first husband separated, soon after she completed her book. In the six months leading up to Ronan’s death in February 2013, his condition deteriorated rapidly and he needed hospice caretakers. Rapp came close to suicide. But in those desperate months, she also threw herself into a new relationship with Kent, a 20-years-older man who was there for her as Ronan was dying and would become her second husband and the father of her daughter, Charlotte (“Charlie”). The acrimonious split from Rick and the astonishment of a new life with Kent – starting in the literal sanctuary of his converted New Mexico chapel, and then moving to California – were two sides of a coin. So were missing Ronan and loving Charlie.

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her.

Karl Ove Knausgaard turned his pretty ordinary life into thousands of pages of autofiction that many readers have found addictive. Adrian valiantly grapples with his six-volume exploration of identity, examining the treatment of time and the dichotomies of intellect versus emotions, self versus other, and life versus fiction. She marvels at the ego that could sustain such a project, and at the seemingly rude decision to use all real names (whereas in her own family memoir she assigned aliases to most major figures). At many points she finds the character of “Karl Ove” insufferable, especially when he’s a teenager in Book 4, and the books’ prose dull. Knausgaard’s focus on male novelists and his stereotypical treatment of feminine qualities, here and in his other work, frequently madden her.

Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

Jones also considers the precedents of wilderness literature and the 1990s memoir boom that paved the way for Wild. I most enjoyed this middle section, which, like Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir, surveys some of the key publications from a burgeoning genre. Another key point of reference is Vivian Gornick, who draws a distinction between “the situation” (the particulars or context) and “the story” (the message) – sometimes the map or message comes first, and sometimes you only discover it as you go along.

As in

As in

Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with

Kingsolver may not be well known for her poetry, but this is actually her second collection of verse after the bilingual Another America/Otra America (1992). The opening segment, “How to Fly,” is full of folk wisdom from nature and the body’s intuitive knowledge. “Pellegrinaggio” is a set of travel poems about accompanying her Italian mother-in-law back to her homeland. “This Is How They Come Back to Us” is composed of elegies for the family’s dead; four shorter remaining sections are inspired by knitting, literature, daily life, and concern for the environment. As with  The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen.

The day starts at 5 a.m. with Justine going for a run, despite a recent heart health scare, and spends time with retirees, an engaged couple spending most of their time in bed, a 16-year-old kayaker, a woman with dementia, and more. We see different aspects of family dynamics as we revisit a previous character’s child, spouse or sibling. I had to laugh at Milly picturing Don Draper during sex with Josh, and at Claire getting an hour to herself without the kids and having no idea what to do with it beyond clean up and make a cup of tea. Moss gets each stream-of-consciousness internal monologue just right, from a frantic mum to a sarcastic teen. Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity and seems sure to follow in the footsteps of Ruby and

Like some lost mid-career gem from Toni Morrison, this novel is meaty with questions of racial and sexual identity and seems sure to follow in the footsteps of Ruby and  The unnamed narrator of Gabrielsen’s fifth novel is a 36-year-old researcher working towards a PhD on the climate’s effects on populations of seabirds, especially guillemots. During this seven-week winter spell in the far north of Norway, she’s left her three-year-old daughter behind with her ex, S, and hopes to receive a visit from her lover, Jo, even if it involves him leaving his daughter temporarily. In the meantime, they connect via Skype when signal allows. Apart from that and a sea captain bringing her supplies, she has no human contact.

The unnamed narrator of Gabrielsen’s fifth novel is a 36-year-old researcher working towards a PhD on the climate’s effects on populations of seabirds, especially guillemots. During this seven-week winter spell in the far north of Norway, she’s left her three-year-old daughter behind with her ex, S, and hopes to receive a visit from her lover, Jo, even if it involves him leaving his daughter temporarily. In the meantime, they connect via Skype when signal allows. Apart from that and a sea captain bringing her supplies, she has no human contact. This is the first collection of the Chinese Singaporean poet’s work to be published in the UK. Infused with Asian history, his elegant verse ranges from elegiac to romantic in tone. Many of the poems are inspired by historical figures and real headlines. There are tributes to soldiers killed in peacetime training and accounts of high-profile car accidents; “The Passenger” is about the ghosts left behind after a tsunami. But there are also poems about the language and experience of love. I also enjoyed the touches of art and legend: “Monologues for Noh Masks” is about the Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, while “Notes on a Landscape” is about Iceland’s geology and folk tales. In most places alliteration and enjambment produce the sonic effects, but there are also a handful of rhymes and half-rhymes, some internal.

This is the first collection of the Chinese Singaporean poet’s work to be published in the UK. Infused with Asian history, his elegant verse ranges from elegiac to romantic in tone. Many of the poems are inspired by historical figures and real headlines. There are tributes to soldiers killed in peacetime training and accounts of high-profile car accidents; “The Passenger” is about the ghosts left behind after a tsunami. But there are also poems about the language and experience of love. I also enjoyed the touches of art and legend: “Monologues for Noh Masks” is about the Pitt-Rivers Museum collection, while “Notes on a Landscape” is about Iceland’s geology and folk tales. In most places alliteration and enjambment produce the sonic effects, but there are also a handful of rhymes and half-rhymes, some internal. I noted the recurring comparison of natural and manmade spaces; outdoors (flowers, blackbirds, birds of prey, the sea) versus indoors (corridors, office life, even Emily Dickinson’s house in Massachusetts). The style shifts from page to page, ranging from prose paragraphs to fragments strewn across the layout. Most of the poems are in recognizable stanzas, though these vary in terms of length and punctuation. Alliteration and repetition (see, as an example of the latter, her poem “The Studio” on the

I noted the recurring comparison of natural and manmade spaces; outdoors (flowers, blackbirds, birds of prey, the sea) versus indoors (corridors, office life, even Emily Dickinson’s house in Massachusetts). The style shifts from page to page, ranging from prose paragraphs to fragments strewn across the layout. Most of the poems are in recognizable stanzas, though these vary in terms of length and punctuation. Alliteration and repetition (see, as an example of the latter, her poem “The Studio” on the  There isn’t, or needn’t be, a contradiction between faith and queerness, as the authors included in this anthology would agree. Many of them are stalwarts at Greenbelt, a progressive Christian summer festival – Church of Scotland minister John L. Bell even came out there, in his late sixties, in 2017. I’m a lapsed regular attendee, so a lot of the names were familiar to me, including those of poets Rachel Mann and Padraig O’Tuama.

There isn’t, or needn’t be, a contradiction between faith and queerness, as the authors included in this anthology would agree. Many of them are stalwarts at Greenbelt, a progressive Christian summer festival – Church of Scotland minister John L. Bell even came out there, in his late sixties, in 2017. I’m a lapsed regular attendee, so a lot of the names were familiar to me, including those of poets Rachel Mann and Padraig O’Tuama.