Recent Literary Awards & Online Events: Folio Prize and Claire Fuller

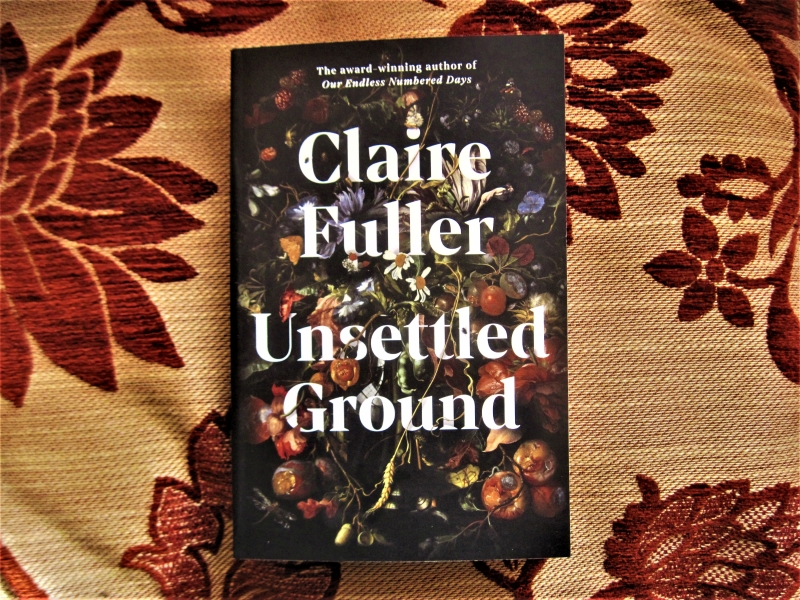

Literary prize season is in full swing! The Women’s Prize longlist, revealed on the 10th, contained its usual mixture of the predictable and the unexpected. I correctly predicted six of the nominees, and happened to have already read seven of them, including Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (more on this below). I’m currently reading another from the longlist, Luster by Raven Leilani, and I have four on order from the library. There are only four that I don’t plan to read, so I’ll be in a fairly good place to predict the shortlist (due out on April 28th). Laura and Rachel wrote detailed reaction posts on which there has been much chat.

Rathbones Folio Prize

This year I read almost the entire Rathbones Folio Prize shortlist because I was lucky enough to be sent the whole list to feature on my blog. The winner, which the Rathbones CEO said would stand as the “best work of literature for the year” out of 80 nominees, was announced on Wednesday in a very nicely put together half-hour online ceremony hosted by Razia Iqbal from the British Library. The Folio scheme also supports writers at all stages of their careers via a mentorship scheme.

It was fun to listen in as the three judges discussed their experience. “Now nonfiction to me seems like rock ‘n’ roll,” Roger Robinson said, “far more innovative than fiction and poetry.” (Though Sinéad Gleeson and Jon McGregor then stood up for the poetry and fiction, respectively.) But I think that was my first clue that the night was going to go as I’d hoped. McGregor spoke of the delight of getting “to read above the categories, looking for freshness, for excitement.” Gleeson said that in the end they had to choose “the book that moved us, that enthralled us.”

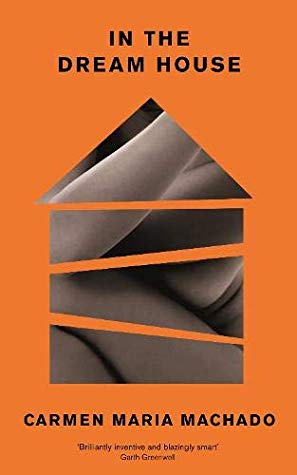

All eight authors had recorded short interview clips about their experience of lockdown and how they experiment with genre and form, and seven (all but Doireann Ní Ghríofa) were on screen for the live announcement. The winner of the £30,000 prize, author of an “exceptional, important” book and teller of “a story that had to be told,” was Carmen Maria Machado for In the Dream House. I was delighted with this result: it was my first choice and is one of the most remarkable memoirs I’ve read. I remember reading it on my Kindle on the way to and from Hungerford for a bookshop event in early March 2020 – my last live event and last train ride in over a year and counting, which only made the reading experience more memorable.

I like what McGregor had to say about the book in the media release: “In the Dream House has changed me – expanded me – as a reader and a person, and I’m not sure how much more we can ask of the books that we choose to celebrate.”

There are now only two previous Folio winners that I haven’t read, the memoir The Return by Hisham Matar and the novel Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli, so I’d like to get those two out from the library soon and complete the set.

Other literary prizes

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

The following day, the Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist was announced. Still in the running are two novels I’ve read and enjoyed, Pew by Catherine Lacey and My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell, and one I’m currently reading (Luster). Of the rest, I’m particularly keen on Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis, and I would also like to read Alligator and Other Stories by Dima Alzayat. I’d love to see Russell win the whole thing. The announcement will be on May 13th. I hope to participate in a shortlist blog tour leading up to it.

I also tuned into the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards ceremony (on YouTube), which was unfortunately marred by sound issues. This year’s three awards went to women: Dervla Murphy (Edward Stanford Outstanding Contribution to Travel Writing), Anita King (Bradt Travel Guides New Travel Writer of the Year; you can read her personal piece on Syria here), and Taran N. Khan for Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul (Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year in association with the Authors’ Club).

Other prize races currently in progress that are worth keeping an eye on:

- The Jhalak Prize for writers of colour in Britain (I’ve read four from the longlist and would be interested in several others if I could get hold of them)

- The Republic of Consciousness Prize for work from small presses (I’ve read two; Doireann Ní Ghríofa gets another chance – fingers crossed for her)

- The Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction (next up for me: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams, to review for BookBrowse)

Claire Fuller

Yesterday evening, I attended the digital book launch for Claire Fuller’s Unsettled Ground (my review will be coming soon). I’ve read all four of her novels and count her among my favorite contemporary writers. I spotted Eric Anderson and Ella Berthoud among the 200+ attendees, and Claire’s agent quoted from Susan’s review – “A new novel from Fuller is always something to celebrate”! Claire read a passage from the start of the novel that introduces the characters just as Dot starts to feel unwell. Uniquely for online events I’ve attended, we got a tour of the author’s writing room, with Alan the (female) cat asleep on the daybed behind her, and her librarian husband Tim helped keep an eye on the chat.

After each novel, as a treat to self, she buys a piece of art. This time, she commissioned a ceramic plate from Sophie Wilson with lines and images from the book painted on it. Live music was provided by her son Henry Ayling, who played acoustic guitar and sang “We Roamed through the Garden,” which, along with traditional folk song “Polly Vaughn,” are quoted in the novel and were Claire’s earworms for two years. There was also a competition to win a chocolate Easter egg, given to whoever came closest to guessing the length of the new novel in words. (It was somewhere around 89,000.)

Good news – she’s over halfway through Book 5!

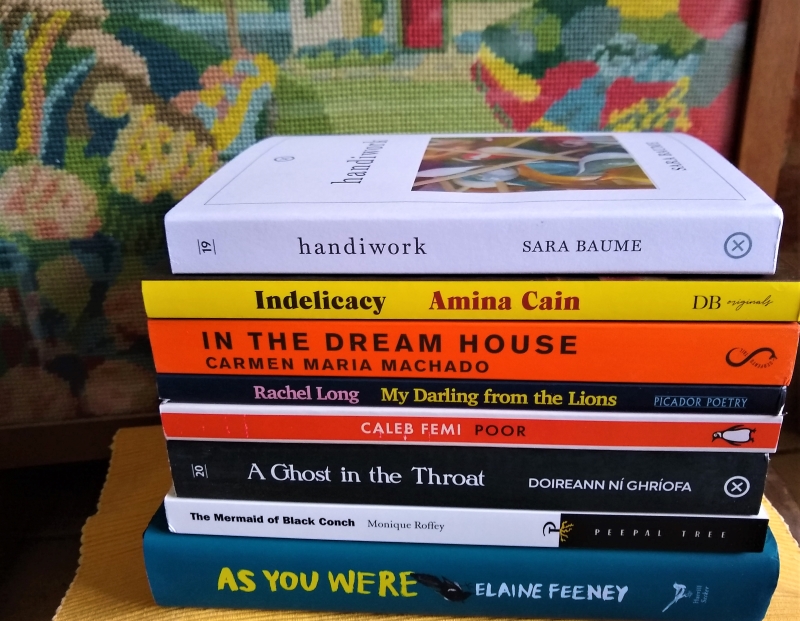

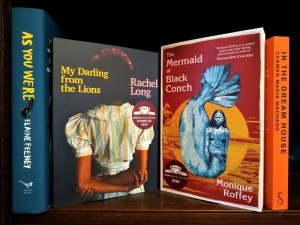

The Rathbones Folio Prize 2021 Shortlist

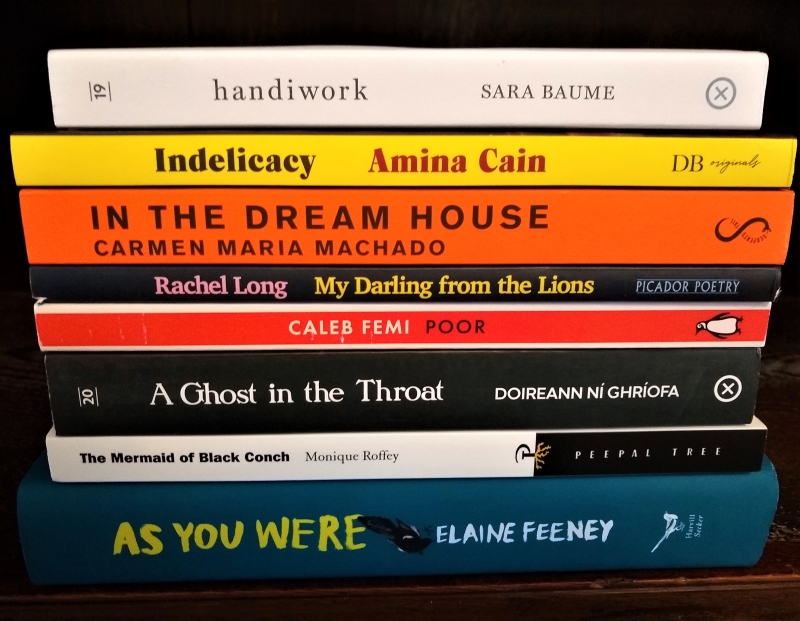

The Rathbones Folio Prize is unique in that nominations come from the Folio Academy, an international group of writers and critics, and any book written in English is eligible, so nonfiction and poetry share space with fiction on the varied shortlist of eight titles:

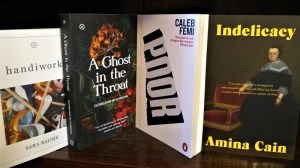

- handiwork by Sara Baume (Tramp Press)

- Indelicacy by Amina Cain (Daunt Books)

- As You Were by Elaine Feeney (Harvill Secker)

- Poor by Caleb Femi (Penguin)

- My Darling from the Lions by Rachel Long (Picador)

- In the Dream House: A Memoir by Carmen Maria Machado (Serpent’s Tail)

- A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa (Tramp Press)

- The Mermaid of Black Conch by Monique Roffey (Peepal Tree Press)

I was delighted to be sent the whole shortlist to feature. I’d already read Rachel Long’s poetry collection and Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir (reviewed here), but I’m keen to start on the rest and will read and review as many as possible before the online prize announcement on Wednesday the 24th. I’m starting with the Baume, Cain, Femi and Roffey.

I was delighted to be sent the whole shortlist to feature. I’d already read Rachel Long’s poetry collection and Carmen Maria Machado’s memoir (reviewed here), but I’m keen to start on the rest and will read and review as many as possible before the online prize announcement on Wednesday the 24th. I’m starting with the Baume, Cain, Femi and Roffey.

For more information on the prize, these eight authors, and the longlist, see the website.

(The remainder of the text in this post comes from the official press release.)

The Rathbones Folio Prize — known as the “writers’ prize” — rewards the best work of literature of the year, regardless of form. It is the only award governed by an international academy of distinguished writers and critics, ensuring a unique quality and consistency in the nomination and judging process.

The judges (Roger Robinson, Sinéad Gleeson, and Jon McGregor) have chosen books by seven women and one man to be in contention for the £30,000 prize which looks for the best fiction, non-fiction and poetry in English from around the world. Six out of the eight titles are by British and Irish writers, with three out of Ireland alone (two of which are published by the same publisher, Tramp Press). The spirit of experimentation is also reflected in the strong showing of independent publishers and small presses (five out of eight).

Chair of judges Roger Robinson says: “It was such a joy to spend detailed and intimate time with the books nominated for the Rathbones Folio Prize and travel deep into their worlds. The judges chose the eight books on the shortlist because they are pushing at the edges of their forms in interesting ways, without sacrificing narrative or execution. The conversations between the judges may have been as edifying as the books themselves. From a judges’ vantage point, the future of book publishing looks incredibly healthy – and reading a book is still one of the most revolutionary things that one can do.”

The 2021 shortlist ranges from Amina Cain’s Indelicacy – a feminist fable about class and desire – and the exploration of the estates of South London through poetry and photography in Caleb Femi’s Poor, to a formally innovative, genre-bending memoir about domestic abuse in Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, and a feminist revision of Caribbean mermaid myths, in Monique Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch.

The 2021 shortlist ranges from Amina Cain’s Indelicacy – a feminist fable about class and desire – and the exploration of the estates of South London through poetry and photography in Caleb Femi’s Poor, to a formally innovative, genre-bending memoir about domestic abuse in Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, and a feminist revision of Caribbean mermaid myths, in Monique Roffey’s The Mermaid of Black Conch.

In the darkly comic novel As You Were, poet Elaine Feeney tackles the intimate histories, institutional failures, and the darkly present past of modern Ireland, while Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat finds the eighteenth-century poet Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill haunting the life of a contemporary young mother, prompting her to turn detective. Doireann Ní Ghríofa is published by Dublin’s Tramp Press, also publishers of Sara Baume’s handiwork – which charts the author’s daily process of making and writing, and explores what it is to create and to live as an artist – while poet Rachel Long’s acclaimed debut collection My Darling from the Lions skewers sexual politics, religious awakenings and family quirks with wit, warmth and precision.

My thanks to the publishers and FMcM Associates for the free copies for review.

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

The latest in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series (I’ve also reviewed their books on

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating.

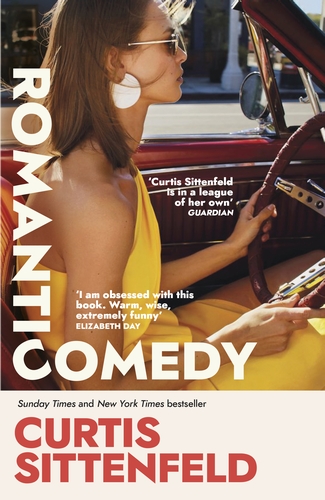

Eight of the 11 stories are in the third person and most protagonists are young or middle-aged women navigating marriage/divorce and motherhood. A driving examiner finds herself in the same situation as her teenage test-taker; a wife finds evidence of her actor husband’s adultery. In “Damascus,” Mia worries her son might be on drugs, but doesn’t question her own self-destructive habits. Inspired by Marie Kondo, Rachel tries to pare her life back to the basics in “CobRa.” In “King Midas,” Oscar learns that all is not golden with his mistress. “Sky Bar” has Fawn stuck in her hometown airport during a blizzard. I particularly liked the ridiculous situations Florida housemates get themselves into in “Pandemic Behavior,” and the second-person “Twist and Shout,” about loving an elderly father even though he’s infuriating. Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

Plain Jane getting the hot guy … that never happens, right? In fact, Sally has a theory about this very dilemma, named after her schlubby TNO office-mate: The Danny Horst Rule states that ordinary men may date and even marry actresses or supermodels, but reverse the genders and it never works. A fundamental lack of confidence means that, whenever she feels too vulnerable, Sally resorts to snarky comedy and sabotages her chances at happiness. But when, midway through the summer of 2020, she gets an out-of-the-blue e-mail from Noah, she wonders if this relationship has potential in the real world. (This, for me, is the peak: when you find out that interest is requited; that the person you’ve been thinking about for years has also been thinking about you. Whatever comes next pales in comparison to this moment.)

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for

In a fragmentary work of autobiography and cultural commentary, the Mexican author investigates pregnancy as both physical reality and liminal state. The linea nigra is a stripe of dark hair down a pregnant woman’s belly. It’s a potent metaphor for the author’s matriarchal line: her grandmother was a doula; her mother is a painter. In short passages that dart between topics, Barrera muses on motherhood, monitors her health, and recounts her dreams. Her son, Silvestre, is born halfway through the book. She gives impressionistic memories of the delivery and chronicles her attempts to write while someone else watches the baby. This is both diary and philosophical appeal—for pregnancy and motherhood to become subjects for serious literature. (See my full review for  It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for

It so happens that May is Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month. Cornwell comes from a deeply literary family; the late John le Carré was her grandfather. Her memoir shimmers with visceral memories of delivering her twin sons in 2018 and the postnatal depression and infections that followed. The details, precise and haunting, twine around a historical collage of words from other writers on motherhood and mental illness, ranging from Margery Kempe to Natalia Ginzburg. Childbirth caused other traumatic experiences from her past to resurface. How to cope? For Cornwell, therapy and writing went hand in hand. This is vivid and resolute, and perfect for readers of Catherine Cho, Sinéad Gleeson and Maggie O’Farrell. (See my full review for  Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for

Jones’s fourth work of fiction contains 11 riveting stories of contemporary life in the American South and Midwest. Some have pandemic settings and others are gently magical; all are true to the anxieties of modern careers, marriage and parenthood. In the title story, the narrator, a harried mother and business school student in Kentucky, seeks to balance the opposing forces of her life and wonders what she might have to sacrifice. The ending elicits a gasp, as does the audacious inconclusiveness of “Exhaust,” a tense tale of a quarreling couple driving through a blizzard. Worry over environmental crises fuels “Ark,” about a pyramid scheme for doomsday preppers. Fans of Nickolas Butler and Lorrie Moore will find much to admire. (Read via Edelweiss. See my full review for  Having read Ruhl’s memoir

Having read Ruhl’s memoir  I reviewed

I reviewed

A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)

A reread of a book that transformed my understanding of gender back in 2006. Morris (d. 2020) was a trans pioneer. Her concise memoir opens “I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl.” Sitting under the family piano, little James knew it, but it took many years – a journalist’s career, including the scoop of the first summiting of Mount Everest in 1953; marriage and five children; and nearly two decades of hormone therapy – before a sex reassignment surgery in Morocco in 1972 physically confirmed it. I was struck this time by Morris’s feeling of having been a spy in all-male circles and taking advantage of that privilege while she could. She speculates that her travel books arose from “incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.” The focus is more on her unchanging soul than on her body, so this is not a sexual tell-all. She paints hers as a spiritual quest toward true identity and there is only joy at new life rather than regret at time wasted in the ‘wrong’ one. (Public library)

This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

This was my third memoir by the author; I reviewed

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

A woman, her partner (R), and their baby son flee a flooded London in search of a place of safety, traveling by car and boat and camping with friends and fellow refugees. “How easily we have got used to it all, as though we knew what was coming all along,” she says. Her baby, Z, tethers her to the corporeal world. What actually happens? Well, on the one hand it’s very familiar if you’ve read any dystopian fiction; on the other hand it is vague because characters only designated by initials are hard to keep straight and the text is in one- or two-sentence or -paragraph chunks punctuated by asterisks (and dull observations): “Often, I am unsure whether something is a bird or a leaf. *** Z likes to eat butter in chunks. *** We are overrun by mice.” etc. It’s touching how Z’s early milestones structure the book, but for the most part the style meant this wasn’t my cup of tea. (Secondhand purchase)

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s

Pick this up right away if you loved Danielle Evans’s

After reviewing Josipovici’s

After reviewing Josipovici’s  Otsuka’s

Otsuka’s

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

Crossing to Safety with Laila (Big Reading Life)

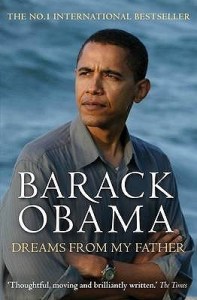

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.

Dreams from My Father by Barack Obama: Remember when there was a U.S. president who thought deeply, searched his soul, and wrote eloquently? I first read this memoir in 2006, when Obama was an up-and-coming Democratic politician who’d given a rousing convention speech. I remembered no details, just the general sweep of Hawaii to Chicago to Kenya. On this reread I engaged most with the first third, in which he remembers a childhood in Hawaii and Indonesia, gives pen portraits of his white mother and absentee Kenyan father, and works out what it means to be black and Christian in America. By age 12, he’d stopped advertising his mother’s race, not wanting to ingratiate himself with white people. By contrast, “To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.” The long middle section on community organizing in Chicago nearly did me in; I had to skim past it to get to his trip to Kenya to meet his paternal relatives – “Africa had become an idea more than an actual place, a new promised land”.  The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot: This Wellcome Book Prize winner about the use of a poor African-American woman’s cells in medical research was one of the first books to turn me onto health-themed reads. I devoured it in a few days in 2010. Once again, I was impressed at the balance between popular science and social history. Skloot conveys the basics of cell biology in a way accessible to laypeople, and uses recreated scenes and dialogue very effectively. I had forgotten the sobering details of the Lacks family experience, including incest, abuse, and STDs. Henrietta had a rural Virginia upbringing and had a child by her first cousin at age 14. At 31 she would be dead of cervical cancer, but the tissue taken from her at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins hospital became an immortal cell line. HeLa is still commonly used in medical experimentation. Consent was a major talking point at our book club Zoom meeting. Cells, once outside a body, cannot be owned, but it looks like exploitation that Henrietta’s descendants are so limited by their race and poverty. I had forgotten how Skloot’s relationship and travels with Henrietta’s unstable daughter, Deborah, takes over the book (as in the film). While I felt a little uncomfortable with how various family members are portrayed as unhinged, I still thought this was a great read.  I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

I had some surprising rereading DNFs. These were once favorites of mine, but for some reason I wasn’t able to recapture the magic: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson, and On Beauty by Zadie Smith. I attempted a second read of John Fowles’s postmodern Victorian pastiche, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, on a mini-break in Lyme Regis, happily reading the first third on location, but I couldn’t make myself finish once we were back home. And A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan was very disappointing a second time; it hasn’t aged well. Lastly, I’ve been stalled in Watership Down for a long time, but do intend to finish my reread.

#6 Violence against women is also the theme of The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld, my novel of 2020 so far. While it ranges across the centuries, it always sticks close to the title location, an uninhabited island off the east coast of Scotland. It cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that is appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. This is not a puzzle book where everything fits together. Instead, it is a haunting echo chamber where elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. A must-read, especially for fans of Claire Fuller, Sarah Moss and Lucy Wood. (See my full

#6 Violence against women is also the theme of The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld, my novel of 2020 so far. While it ranges across the centuries, it always sticks close to the title location, an uninhabited island off the east coast of Scotland. It cycles through its three strands in an ebb and flow pattern that is appropriate to the coastal setting and creates a sense of time’s fluidity. This is not a puzzle book where everything fits together. Instead, it is a haunting echo chamber where elements keep coming back, stinging a little more each time. A must-read, especially for fans of Claire Fuller, Sarah Moss and Lucy Wood. (See my full  Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of

Such sentiments also reminded me of the relatable, but by no means ground-breaking, contents of  A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life.

A few years ago I read Royle’s An English Guide to Birdwatching, one of the stranger novels I’ve ever come across (it brings together a young literary critic’s pet peeves, a retired couple’s seaside torture by squawking gulls, the confusion between the two real-life English novelists named Nicholas Royle, and bird-themed vignettes). It was joyfully over-the-top, full of jokes and puns as well as trenchant observations about modern life. Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via

Wizenberg announced her coming-out and her separation from Brandon on her blog, so I was aware of all this for the last few years and via