Six Degrees of Separation: From The End of the Affair to Nutshell

This month we begin with The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, a perfect excuse for me to review a novel I finished more than a year ago. This was only my second novel from Greene, after The Quiet American many a year ago. It’s subtle: low on action and majoring on recollection and regret. Mostly what we get are the bitter memories of Maurice Bendrix, a writer who had an affair with his clueless friend Henry’s wife Sarah during the last days of the Second World War. After she broke up with him, he remained obsessed with her and hired Parkis, a lower-class private detective, to figure out why. To his surprise, Sarah’s diaries revealed, not that she’d taken up with another man, but that she’d found religion. Maurice finds himself in the odd position of being jealous of … God? (More thoughts here.)

This month we begin with The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, a perfect excuse for me to review a novel I finished more than a year ago. This was only my second novel from Greene, after The Quiet American many a year ago. It’s subtle: low on action and majoring on recollection and regret. Mostly what we get are the bitter memories of Maurice Bendrix, a writer who had an affair with his clueless friend Henry’s wife Sarah during the last days of the Second World War. After she broke up with him, he remained obsessed with her and hired Parkis, a lower-class private detective, to figure out why. To his surprise, Sarah’s diaries revealed, not that she’d taken up with another man, but that she’d found religion. Maurice finds himself in the odd position of being jealous of … God? (More thoughts here.)

#1 I asked myself if I’d ever read another book where someone was jealous of a concept rather than a fellow human being, and finally came up with one. I enjoyed Cooking as Fast as I Can by Cat Cora even though I wasn’t aware of this Food Network celebrity and restaurateur. Her memoir focuses on her Mississippi upbringing in a half-Greek adoptive family and the challenges of being gay in the South. Separate obsessions plagued her marriage; I remember at one point she gave her wife an ultimatum: it’s either me or the hot yoga.

#1 I asked myself if I’d ever read another book where someone was jealous of a concept rather than a fellow human being, and finally came up with one. I enjoyed Cooking as Fast as I Can by Cat Cora even though I wasn’t aware of this Food Network celebrity and restaurateur. Her memoir focuses on her Mississippi upbringing in a half-Greek adoptive family and the challenges of being gay in the South. Separate obsessions plagued her marriage; I remember at one point she gave her wife an ultimatum: it’s either me or the hot yoga.

#2 Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It by Geoff Dyer is one of my favourite-ever book titles. The title is his proposed idea for a self-help book, but … wait for the punchline … he couldn’t be bothered to write it. It’s a book of disparate travel essays, with him as the bumbling antihero, sluggish and stoned. This wasn’t one of his better books, but his descriptions and one-liners are always amusing (my review).

#2 Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It by Geoff Dyer is one of my favourite-ever book titles. The title is his proposed idea for a self-help book, but … wait for the punchline … he couldn’t be bothered to write it. It’s a book of disparate travel essays, with him as the bumbling antihero, sluggish and stoned. This wasn’t one of his better books, but his descriptions and one-liners are always amusing (my review).

#3 Another book with a fantastic title that has nothing to do with the contents: Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls by David Sedaris. Again, not my favourite of his essay collections (try Me Talk Pretty One Day or When You Are Engulfed in Flames instead), but he’s reliable for laughs.

#3 Another book with a fantastic title that has nothing to do with the contents: Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls by David Sedaris. Again, not my favourite of his essay collections (try Me Talk Pretty One Day or When You Are Engulfed in Flames instead), but he’s reliable for laughs.

#4 No more about owls than the previous one; Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame is an autobiographical novel that tells the same story as her An Angel at My Table trilogy (but less compellingly): a hardscrabble upbringing in New Zealand and mental illness that led to incarceration in psychiatric hospitals. The title phrase is from Ariel’s song in The Tempest, which the Withers siblings learn at school. I’ve been ‘reading’ this for nearly a year and a half; really, it’s mostly been on the set-aside shelf for that time.

#4 No more about owls than the previous one; Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame is an autobiographical novel that tells the same story as her An Angel at My Table trilogy (but less compellingly): a hardscrabble upbringing in New Zealand and mental illness that led to incarceration in psychiatric hospitals. The title phrase is from Ariel’s song in The Tempest, which the Withers siblings learn at school. I’ve been ‘reading’ this for nearly a year and a half; really, it’s mostly been on the set-aside shelf for that time.

#5 Another title drawn from Shakespeare: there are more things by Yara Rodrigues Fowler is one of my Most Anticipated Books of 2022. It’s about a female friendship that links Brazil and London. I’m holding out hope for a review copy.

#5 Another title drawn from Shakespeare: there are more things by Yara Rodrigues Fowler is one of my Most Anticipated Books of 2022. It’s about a female friendship that links Brazil and London. I’m holding out hope for a review copy.

#6 Fowler’s title comes from Hamlet, which provides the plot for Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, one of his strongest novels of recent years. Within a few pages, I was captivated and utterly convinced by the voice of this contemporary, in utero Hamlet. Not even born and already a snob with an advanced vocabulary and a taste for fine wine, this foetus is a delight to spend time with. His captive state pairs perfectly with Hamlet’s existential despair, but also makes him (and us as readers) part of the conspiracy: even as he wants justice for his father, he has to hope his mother and uncle will get away with their crime; his future depends on it.

#6 Fowler’s title comes from Hamlet, which provides the plot for Ian McEwan’s Nutshell, one of his strongest novels of recent years. Within a few pages, I was captivated and utterly convinced by the voice of this contemporary, in utero Hamlet. Not even born and already a snob with an advanced vocabulary and a taste for fine wine, this foetus is a delight to spend time with. His captive state pairs perfectly with Hamlet’s existential despair, but also makes him (and us as readers) part of the conspiracy: even as he wants justice for his father, he has to hope his mother and uncle will get away with their crime; his future depends on it.

Where will your chain take you? Join us for #6Degrees of Separation! (Hosted on the first Saturday of each month by Kate W. of Books Are My Favourite and Best.)

Have you read any of my selections? Tempted by any you didn’t know before?

Fairy Tales, Outlaws, Experimental Prose: Three More January Novels

Today I’m featuring three more works of fiction that were released this month, as a supplement to yesterday’s review of Mrs Death Misses Death. Although the four are hugely different in setting and style, and I liked some better than others (such is the nature of reading and book reviewing), together they’re further proof – as if we needed it – that female authors are pushing the envelope. I wouldn’t be surprised to see any or all of these on the Women’s Prize longlist in March.

The Charmed Wife by Olga Grushin

What happens next for Cinderella?

What happens next for Cinderella?

Grushin’s fourth novel unpicks a classic fairy tale narrative, starting 13.5 years into a marriage when, far from being starry-eyed with love for Prince Roland, the narrator hates her philandering husband and wants him dead. As she retells the Cinderella story to her children one bedtime, it only underscores how awry her own romance has gone: “my once-happy ending has proved to be only another beginning, a prelude to a tale dimmer, grittier, far more ambiguous, and far less suitable for children”. She gathers Roland’s hair and nails and goes to a witch for a spell, but her fairy godmother shows up to interfere. The two embark on a good cop/bad cop act as the princess runs backward through her memories: one defending Roland and the other convinced he’s a scoundrel.

Part One toggles back and forth between flashbacks (in the third person and past tense) and the present-day struggle for the narrator’s soul. She comes to acknowledge her own ignorance and bad behaviour. “All I want is to be free—free of him, free of my past, free of my story. Free of myself, the way I was when I was with him.” In Part Two, as the princess tries out different methods of escape, Grushin coyly inserts allusions to other legends and nursery rhymes: a stepsister lives with her many children in a house shaped like a shoe; the witch tells a variation on the Bluebeard story; the fairy godmother lives in a Hansel and Gretel-like candy cottage; the narrator becomes a maid for 12 slovenly sisters; and so on.

The plot feels fairly aimless in this second half, and the mixture of real-world and fantasy elements is peculiar. I much preferred Grushin’s previous book, Forty Rooms (and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of her chief inspirations). However, her two novels share a concern with how women’s ambitions can take a backseat to their roles, and both weave folktales and dreams into a picture of everyday life. But my favourite part of The Charmed Wife was the subplot: interludes about Brie and Nibbles, the princess’s pet mice; their lives being so much shorter, they run through many generations of a dramatic saga while the narrator (whose name we do finally learn, just a few pages from the end) is stuck in place.

The plot feels fairly aimless in this second half, and the mixture of real-world and fantasy elements is peculiar. I much preferred Grushin’s previous book, Forty Rooms (and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, one of her chief inspirations). However, her two novels share a concern with how women’s ambitions can take a backseat to their roles, and both weave folktales and dreams into a picture of everyday life. But my favourite part of The Charmed Wife was the subplot: interludes about Brie and Nibbles, the princess’s pet mice; their lives being so much shorter, they run through many generations of a dramatic saga while the narrator (whose name we do finally learn, just a few pages from the end) is stuck in place.

With thanks to Hodder & Stoughton for the free copy for review.

Outlawed by Anna North

I was a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which cobbles together the story of the title character, a bisexual filmmaker, from accounts by the people who knew her best. Outlawed, an alternative history/speculative take on the traditional Western, could hardly be more different. In a subtly different version of the United States, everyone now alive in the 1890s is descended from those who survived a vicious 1830s flu epidemic. The duty to repopulate the nation has led to a cult of fertility and devotion to the Baby Jesus. From her mother, a midwife and herbalist, Ada has learned the basics of medical care, but the causes of barrenness remain a mystery and childlessness is perceived as a curse.

I was a huge fan of North’s previous novel, The Life and Death of Sophie Stark, which cobbles together the story of the title character, a bisexual filmmaker, from accounts by the people who knew her best. Outlawed, an alternative history/speculative take on the traditional Western, could hardly be more different. In a subtly different version of the United States, everyone now alive in the 1890s is descended from those who survived a vicious 1830s flu epidemic. The duty to repopulate the nation has led to a cult of fertility and devotion to the Baby Jesus. From her mother, a midwife and herbalist, Ada has learned the basics of medical care, but the causes of barrenness remain a mystery and childlessness is perceived as a curse.

Ada marries at 17 and fails to get pregnant within a year. After an acquaintance miscarries, rumours start to spread about Ada being a witch. Kicked out by her mother-in-law, she takes shelter first at a convent and then with the Hole in the Wall gang. She’ll be the doctor to this band of female outlaws who weren’t cut out for motherhood and shunned marriage – including lesbians, a mixed-race woman, and their leader, the Kid, who is nonbinary. The Kid is a mentally tortured prophet with a vision of making the world safe for people like them (“we were told a lie about God and what He wants from us”), mainly by, Robin Hood-like, redistributing wealth through hold-ups and bank robberies. Ada, who longs to conduct proper research into reproductive health rather than relying on religious propaganda, falls for another gender nonconformist, Lark, and does what she can to make the Kid’s dream a reality.

Reese Witherspoon choosing this for her Hello Sunshine book club was a great chance for North’s work to get more attention. However, I felt that the ideas behind this novel were more noteworthy than the execution. The similarity to The Handmaid’s Tale is undeniable, though I liked this a bit more. I most enjoyed the medical and religious themes, and appreciated the attention to childless and otherwise unconventional women. But the setup is so condensed and the consequences of the gang’s major heist so rushed that I wondered if the novel needed another 100 pages to stretch its wings. I’ll just have to await North’s next book.

With thanks to W&N for the proof copy for review.

little scratch by Rebecca Watson

I love a circadian narrative and had heard interesting things about the experimental style used in this debut novel. I even heard Watson read a passage from it as part of the Faber Live Fiction Showcase and found it very funny and engaging. But I really should have tried an excerpt before requesting this for review; I would have seen at a glance that it wasn’t for me. I don’t have a problem with prose being formatted like poetry (Girl, Woman, Other; Stubborn Archivist; the prologue of Wendy McGrath’s Santa Rosa; parts of Mrs Death Misses Death), but here it seemed to me that it was only done to alleviate the tedium of the contents.

I love a circadian narrative and had heard interesting things about the experimental style used in this debut novel. I even heard Watson read a passage from it as part of the Faber Live Fiction Showcase and found it very funny and engaging. But I really should have tried an excerpt before requesting this for review; I would have seen at a glance that it wasn’t for me. I don’t have a problem with prose being formatted like poetry (Girl, Woman, Other; Stubborn Archivist; the prologue of Wendy McGrath’s Santa Rosa; parts of Mrs Death Misses Death), but here it seemed to me that it was only done to alleviate the tedium of the contents.

A young woman who, like Watson, works for a newspaper, trudges through a typical day: wake up, get ready, commute to the office, waste time and snack in between doing bits of work, get outraged about inconsequential things, think about her boyfriend (only ever referred to as “my him” – probably my biggest specific pet peeve about the book), and push down memories of a sexual assault. Thus, the only thing that really happens happened before the book even started. Her scratching, to the point of open wounds and scabs, seems like a psychosomatic symptom of unprocessed trauma. By the end, she’s getting ready to tell her boyfriend about the assault, which seems like a step in the right direction.

I might have found Watson’s approach captivating in a short story, or as brief passages studded in a longer narrative. At first it’s a fun puzzle to ponder how these mostly unpunctuated words, dotted around the pages in two to six columns, fit together – should one read down each column, or across each row, or both? – but when all the scattershot words are only there to describe a train carriage filling up or repetitive quotidian actions (sifting through e-mails, pedalling a bicycle), the style soon grates. You may have more patience with it than I did if you loved A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing or books by Emma Glass.

A favourite passage: “got to do this thing again, the waking up thing, the day thing, the work thing, disentangling from my duvet thing, this is something, this is a thing I have to do then,” [appears all as one left-aligned paragraph]

With thanks to Faber & Faber for the free copy for review.

Tomorrow I’ll review three nonfiction works published in January, all on a medical theme.

What recent releases can you recommend?

A Report on My Most Anticipated Reads & The Ones that Got Away

Between my lists in January and June, I highlighted 45 of the 2019 releases I was most looking forward to reading. Here’s how I did:

Read: 28 [Disappointments (rated

or

): 12]

Currently reading: 1

Abandoned partway through: 5

Lost interest in reading: 1

Haven’t managed to find yet: 9

Languishing on my Kindle; I still have vague intentions to read: 1

To my dismay, it appears I’m not very good at predicting which books I’ll love; I would have gladly given 43% of the ones I read a miss, and couldn’t finish another 11%. Too often, the blurb is tempting or I loved the author’s previous book(s), yet the book doesn’t live up to my expectations. And I still have 376 books published in 2019 on my TBR, which is well over a year’s reading. For the list to keep growing at that annual rate is simply unsustainable.

Thus, I’m gradually working out a 2020 strategy that involves many fewer review copies. For strings-free access to new releases I’m keen to read, I’ll go via my local library. I can still choose to review new and pre-release fiction for BookBrowse, and nonfiction for Kirkus and the TLS. If I’m desperate to read an intriguing-sounding new book and can’t find it elsewhere, there’s always NetGalley or Edelweiss, too. I predict my FOMO will rage, but I’m trying to do myself a favor by waiting most of the year to find out which are truly the most worthwhile books rather than prematurely grabbing at everything that might be interesting.

I regret not having time to finish two 2019 novels I’m currently reading that are so promising they likely would have made at least my runners-up list had I finished them in time. I’m only a couple of chapters into The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins (on the Costa Awards debut shortlist), a Gothic pastiche about a Jamaican maidservant on trial for killing her master and mistress (doubly intended) in Georgian London, but enjoying it very much. I’m halfway through The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall, a quiet character study of co-pastors and their wives and how they came to faith (or not); it is lovely and simply cannot be rushed.

The additional 2019 releases I most wished I’d found time for before the end of this year are:

All This Could Be Yours by Jami Attenberg

Your House Will Pay by Steph Cha

Dominicana by Angie Cruz

&

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado: I’ve heard that this is an amazing memoir of a same-sex abusive relationship, written in an experimental style. It was personally recommended to me by Yara Rodrigues Fowler at the Young Writer of the Year Award ceremony, and also made Carolyn Oliver’s list of nonfiction recommendations.

Luckily, I have another chance at these four since they’re all coming out in the UK in January; I have one as a print proof (Cruz) and the others as NetGalley downloads. I also plan to skim Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men by Caroline Criado Perez, a very important new release, before it’s due back at the library.

The biggest release of 2019 is another that will have to wait until 2020: I know I made a lot of noise about boycotting The Testaments, but I’ve gradually come round to the idea of reading it, and was offered a free hardback to read as a part of an online book club starting on the 13th, so I’m currently rereading Handmaid’s to be ready to start the sequel in the new year.

The biggest release of 2019 is another that will have to wait until 2020: I know I made a lot of noise about boycotting The Testaments, but I’ve gradually come round to the idea of reading it, and was offered a free hardback to read as a part of an online book club starting on the 13th, so I’m currently rereading Handmaid’s to be ready to start the sequel in the new year.

Here’s the books I’m packing for the roughly 48 hours we’ll spend at my in-laws’ over Christmas. (Excessive, I know, but I’m a dabbler, and like to keep my options open!) A mixture of current reads, including a fair bit of suspense and cozy holiday stuff, with two lengthy autobiographies, an enormous Victorian pastiche, and an atmospheric nature/travel book waiting in the wings. I find that the holidays can be a good time to start some big ol’ books I’ve meant to read for ages.

Left stack: to start and read gradually over the next couple of months; right stack: from the currently reading pile.

I’ll be back on the 26th to start the countdown of my favorite books of the year, starting with fiction.

Merry Christmas!

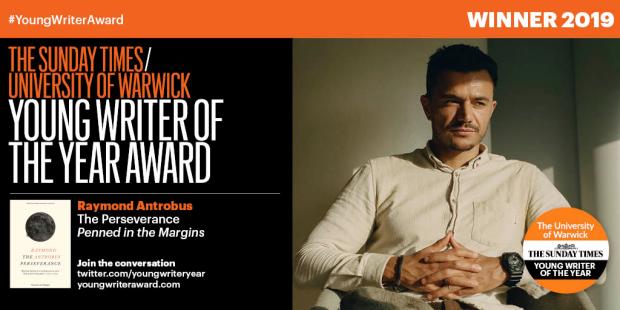

Young Writer of the Year Award Ceremony

It was great to be back at the London Library for last night’s Young Writer of the Year Award prize-giving ceremony. I got to meet Anne Cater (Random Things through my Letterbox) from the shadow panel, who’s coordinated a few blog tours I’ve participated in, as well as Ova Ceren (Excuse My Reading). It was also good to see shadow panelist Linda (Linda’s Book Bag) again and hang out with Clare (A Little Blog of Books), also on the shadow panel in my year, and Eric (Lonesome Reader), who seems to get around to every London literary event.

In case you haven’t heard, the shadow panel chose Salt Slow by Julia Armfield as their very deserving winner, but the official winner was Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance. In all honesty, I’d given no thought to the possibility of it winning, mostly because Antrobus has already won several major prizes for the book, including this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize (I reviewed it for the Prize’s blog tour). Now, there’s no rule saying you can’t win multiple prizes for the same book, but what struck me strangely about this case is that Kate Clanchy was a judge for both the Folio Prize and the Young Writer Award.

In case you haven’t heard, the shadow panel chose Salt Slow by Julia Armfield as their very deserving winner, but the official winner was Raymond Antrobus for his poetry collection The Perseverance. In all honesty, I’d given no thought to the possibility of it winning, mostly because Antrobus has already won several major prizes for the book, including this year’s £30,000 Rathbones Folio Prize (I reviewed it for the Prize’s blog tour). Now, there’s no rule saying you can’t win multiple prizes for the same book, but what struck me strangely about this case is that Kate Clanchy was a judge for both the Folio Prize and the Young Writer Award.

Antrobus seemed genuinely taken aback by his win and gave a very gracious speech in which he said that he looked forward to all the shortlistees contributing to the canon of English literature. He was quickly whisked away for a photo shoot, so I didn’t get a chance to congratulate him or have my book signed, but I did get to meet Julia Armfield and Yara Rodrigues Fowler and get their autographs.

Some interesting statistics for you: in three of the past four years the shadow panel has chosen a short story collection as its winner (and they say no one likes short stories these days!). In none of those four years did the shadow panel correctly predict the official winner – so, gosh, is it the kiss of death to be the shadow panel winner?!

In the official press release, chair of judges and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes that The Perseverance is “both very personal and immensely resonant. The result is a memoir in verse very, very affecting and fresh.” Poet Kate Clanchy adds, “we wanted to find a writer who both speaks for now and who we were confident would continue to produce valuable, central work. … it was the humanity of the book, its tempered kindness, and the commitment not just to recognising difference but to the difficult act of forgiveness that made us confident we had found a winner for this extraordinary year.”

In the official press release, chair of judges and Sunday Times literary editor Andrew Holgate writes that The Perseverance is “both very personal and immensely resonant. The result is a memoir in verse very, very affecting and fresh.” Poet Kate Clanchy adds, “we wanted to find a writer who both speaks for now and who we were confident would continue to produce valuable, central work. … it was the humanity of the book, its tempered kindness, and the commitment not just to recognising difference but to the difficult act of forgiveness that made us confident we had found a winner for this extraordinary year.”

Also present at the ceremony were Sarah Moss (who teaches at the University of Warwick, the Award’s new co-sponsor) and Katya Taylor. I could have sworn I spotted Deborah Levy, too, but after conferring with other book bloggers we decided it was just someone who looked a lot like her.

In any event, it was lovely to see London all lit up with Christmas lights and to spend a couple of hours celebrating up-and-coming writing talent. (And I just managed to catch the last train home and avoid a rail replacement bus nightmare.)

Looking forward to next year already!

November Plans: Novellas, Margaret Atwood Reading Month & More

This is my fourth year joining Laura Frey and others in reading mostly novellas in November. Last year Laura put together a history of the challenge (here); it has had various incarnations but has no particular host or rules. Join us if you like! (#NovNov and #NovellasinNovember) The definition of a novella is loose – it’s based more on the word count than the number of pages – so it’s up to you what you’d like to classify as one. I generally limit myself to books of 150 pages or fewer, though I might go as high as 180-some if there aren’t that many words on a page. Some, including Laura and Susan, would be as generous as 200.

I’ve trawled my shelves for fiction and nonfiction stacks to select from, as well as a few volumes that include several novellas (I’d plan on reading at least the first one) and some slightly longer novels (150–190 pages) for backups. [From the N. West volume, I just have the 52-page novella The Dream Life of Balso Snell, his debut, to read. The Tangye book with the faded cover is Lama.] Also available on my Kindle are The Therapist by Nial Giacomelli*, Record of a Night too Brief by Hiromi Kawakami, Childhood: Two Novellas by Gerard Reve, and Milton in Purgatory by Edward Vass* (both *Fairlight Moderns Novellas, as is Atlantic Winds by William Prendiville).

Other November reading plans…

Margaret Atwood Reading Month

This is the second year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. This year they’re having a special The Handmaid’s Tale/The Testaments theme, but even if you’re avoiding the sequel, join us in reading one or more Atwood works of your choice. She has so much to choose from! Last year I read The Edible Woman and Surfacing. This year I’ve earmarked copies of the novel The Robber Bride (1993) and Moral Disorder (2006), a linked short story collection, both of which I got for free – the former from the free bookshop where I volunteer, and the latter from a neighbor who was giving it away.

This is the second year of #MARM, hosted by Canadian bloggers extraordinaires Marcie of Buried in Print and Naomi of Consumed by Ink. This year they’re having a special The Handmaid’s Tale/The Testaments theme, but even if you’re avoiding the sequel, join us in reading one or more Atwood works of your choice. She has so much to choose from! Last year I read The Edible Woman and Surfacing. This year I’ve earmarked copies of the novel The Robber Bride (1993) and Moral Disorder (2006), a linked short story collection, both of which I got for free – the former from the free bookshop where I volunteer, and the latter from a neighbor who was giving it away.

Nonfiction November

I don’t usually participate in this challenge because nonfiction makes up at least 40% of my reading anyway, but last year I enjoyed putting together some fiction and nonfiction pairings and ‘being the expert’ on women’s religious memoirs, a subgenre I have a couple of books to add to this year. So I will probably end up doing at least one post. The full schedule is here.

Young Writer of the Year Award

Being on the shadow panel for the Sunday Times/PFD Young Writer of the Year Award was a highlight of 2017 for me. I was sad to not be able to attend any of the events last year. I’m excited for this year’s shadow panelists, a couple of whom are blogging friends (one I’ve met IRL), and I look forward to following along with the nominated books and attending the prize ceremony at the London Library on December 5th.

With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist, which is to be announced on November 3rd. I have my fingers crossed for Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Daisy Johnson, Elizabeth Macneal, Stephen Rutt and Lara Williams; I expect we may also see repeat appearances from one of the poets recognized by the Forward Prizes and Guy Gunaratne, the winner of the 2019 Dylan Thomas Prize.

With any luck I will already have read at least one or two books from the shortlist, which is to be announced on November 3rd. I have my fingers crossed for Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Daisy Johnson, Elizabeth Macneal, Stephen Rutt and Lara Williams; I expect we may also see repeat appearances from one of the poets recognized by the Forward Prizes and Guy Gunaratne, the winner of the 2019 Dylan Thomas Prize.

Any reading plans for November? Will you be joining in with novellas, Margaret Atwood’s books or Nonfiction November?

This year we can expect new fiction from Julian Barnes, Carol Birch, Jessie Burton, Jennifer Egan, Karen Joy Fowler, David Guterson, Sheila Heti, John Irving (perhaps? at last), Liza Klaussman, Benjamin Myers, Julie Otsuka, Alex Preston and Anne Tyler; a debut novel from Emilie Pine; second memoirs from Amy Liptrot and Wendy Mitchell; another wide-ranging cultural history/self-help book from Susan Cain; another medical history from Lindsey Fitzharris; a biography of the late Jan Morris; and much more. (Already I feel swamped, and this in a year when I’ve said I want to

This year we can expect new fiction from Julian Barnes, Carol Birch, Jessie Burton, Jennifer Egan, Karen Joy Fowler, David Guterson, Sheila Heti, John Irving (perhaps? at last), Liza Klaussman, Benjamin Myers, Julie Otsuka, Alex Preston and Anne Tyler; a debut novel from Emilie Pine; second memoirs from Amy Liptrot and Wendy Mitchell; another wide-ranging cultural history/self-help book from Susan Cain; another medical history from Lindsey Fitzharris; a biography of the late Jan Morris; and much more. (Already I feel swamped, and this in a year when I’ve said I want to  To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara [Jan. 11, Picador / Doubleday] You’ll see this on just about every list; her fans are legion after the wonder that was

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara [Jan. 11, Picador / Doubleday] You’ll see this on just about every list; her fans are legion after the wonder that was

How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu [Jan. 18, Bloomsbury / William Morrow] Amazing author name! Similar to the Yanagihara what with the century-hopping and future scenario, a feature common in 2020s literature – a throwback to Cloud Atlas? I’m also reminded of the premise of Under the Blue, one of my favourites from last year. “Once unleashed, the Arctic Plague will reshape life on Earth for generations to come.”

How High We Go in the Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu [Jan. 18, Bloomsbury / William Morrow] Amazing author name! Similar to the Yanagihara what with the century-hopping and future scenario, a feature common in 2020s literature – a throwback to Cloud Atlas? I’m also reminded of the premise of Under the Blue, one of my favourites from last year. “Once unleashed, the Arctic Plague will reshape life on Earth for generations to come.” How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman [March 29, Scribner] I enjoyed her earlier story collection,

How Strange a Season by Megan Mayhew Bergman [March 29, Scribner] I enjoyed her earlier story collection,

Search by Michelle Huneven [April 28, Penguin] A late addition to my list thanks to the

Search by Michelle Huneven [April 28, Penguin] A late addition to my list thanks to the

You Have a Friend in 10a: Stories by Maggie Shipstead [May 19, Transworld / May 17, Knopf] Shipstead’s Booker-shortlisted doorstopper, Great Circle, ironically, never took off for me; I’m hoping her short-form storytelling will work out better. “Diving into eclectic and vivid settings, from an Olympic village to a deathbed in Paris to a Pacific atoll, … Shipstead traverses ordinary and unusual realities with cunning, compassion, and wit.”

You Have a Friend in 10a: Stories by Maggie Shipstead [May 19, Transworld / May 17, Knopf] Shipstead’s Booker-shortlisted doorstopper, Great Circle, ironically, never took off for me; I’m hoping her short-form storytelling will work out better. “Diving into eclectic and vivid settings, from an Olympic village to a deathbed in Paris to a Pacific atoll, … Shipstead traverses ordinary and unusual realities with cunning, compassion, and wit.”

Horse by Geraldine Brooks [June 2, Little, Brown / June 14, Viking] You guessed it, another tripartite 1800s–1900s–2000s narrative! With themes of slavery, art and general African American history. I’m not big on horses, at least not these days, but Brooks’s

Horse by Geraldine Brooks [June 2, Little, Brown / June 14, Viking] You guessed it, another tripartite 1800s–1900s–2000s narrative! With themes of slavery, art and general African American history. I’m not big on horses, at least not these days, but Brooks’s

A Brief History of Living Forever by Jaroslav Kalfar [Aug. 4, Sceptre / Little, Brown] His

A Brief History of Living Forever by Jaroslav Kalfar [Aug. 4, Sceptre / Little, Brown] His  The Cure for Sleep by Tanya Shadrick [Jan. 20, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] Nature memoir / self-help. “On return from near-death, Shadrick vows to stop sleepwalking through life. … Around the care of young children, she starts to play with the shape and scale of her days: to stray from the path, get lost in the woods, make bargains with strangers … she moves beyond her respectable roles as worker, wife and mother in a small town.” [Review copy]

The Cure for Sleep by Tanya Shadrick [Jan. 20, Weidenfeld & Nicolson] Nature memoir / self-help. “On return from near-death, Shadrick vows to stop sleepwalking through life. … Around the care of young children, she starts to play with the shape and scale of her days: to stray from the path, get lost in the woods, make bargains with strangers … she moves beyond her respectable roles as worker, wife and mother in a small town.” [Review copy] The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness by Meghan O’Rourke [March 1, Riverhead] O’Rourke wrote

The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness by Meghan O’Rourke [March 1, Riverhead] O’Rourke wrote

Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return by Rebecca Mead [April 21, Grove Press UK / Feb. 8, Knopf] I enjoyed Mead’s

Home/Land: A Memoir of Departure and Return by Rebecca Mead [April 21, Grove Press UK / Feb. 8, Knopf] I enjoyed Mead’s

Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble by Carolyn Oliver [Aug. 19, Univ. of Utah Press] Carolyn used to blog at

Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble by Carolyn Oliver [Aug. 19, Univ. of Utah Press] Carolyn used to blog at

Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s

Like Hannah Kent’s The Good People and Sarah Perry’s  These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of

These are essays for everyone who has had a mother – not just everyone who has been a mother. I enjoyed every piece separately, but together they form a vibrant collage of women’s experiences. Care has been taken to represent a wide range of situations and attitudes. The reflections are honest about physical as well as emotional changes, with midwife Leah Hazard (author of  Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder.

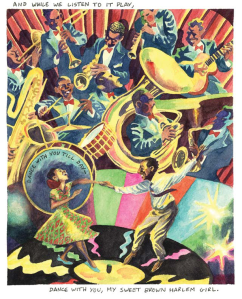

Val McDermid and Jeanette Winterson are among the fans of this, Penguin’s lead debut title of 2020. When a young woman is found drowned at a popular suicide site in the Manchester area, the police plan to dismiss the case as an open-and-shut suicide. But the others at the women’s shelter where Katie Straw worked aren’t convinced, and for nearly the whole span of this taut psychological thriller readers are left to wonder if it was suicide or murder. Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

Poems to See by: A Comic Artist Interprets Great Poetry by Julian Peters

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires.

“Emergency police fire, or ambulance?” The young female narrator of this debut novel lives in Sydney and works for Australia’s emergency call service. Over her phone headset she gets appalling glimpses into people’s worst moments: a woman cowers from her abusive partner; a teen watches his body-boarding friend being attacked by a shark. Although she strives for detachment, her job can’t fail to add to her anxiety – already soaring due to the country’s flooding and bush fires. With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.

With the Second World War only recently ended and nothing awaiting him apart from the coal mine where his father works, sixteen-year-old Robert Appleyard sets out on a journey. From his home in County Durham, he walks southeast, doing odd jobs along the way in exchange for food and lodgings. One day he wanders down a lane near Robin Hood’s Bay and gets a surprisingly warm welcome from a cottage owner, middle-aged Dulcie Piper, who invites him in for tea and elicits his story. Almost accidentally, he ends up staying for the rest of the summer, clearing scrub and renovating her garden studio.

Reckless Paper Birds by John McCullough: From the Costa Awards shortlist. I was struck by the hard-hitting, never-obvious verbs, and the repeating imagery. Flashes of nature burst into a footloose life in Brighton. The poems are by turns randy, neurotic, playful and nostalgic. In “Flock of Paper Birds,” one of my favorites, the poet tries to reconcile the faith he grew up in with his unabashed sexuality.

Reckless Paper Birds by John McCullough: From the Costa Awards shortlist. I was struck by the hard-hitting, never-obvious verbs, and the repeating imagery. Flashes of nature burst into a footloose life in Brighton. The poems are by turns randy, neurotic, playful and nostalgic. In “Flock of Paper Birds,” one of my favorites, the poet tries to reconcile the faith he grew up in with his unabashed sexuality.

Flèche by Mary Jean Chan: Exquisite poems of love and longing, with the speaker’s loyalties always split between head and heart, flesh and spirit. Over it all presides the figure of a mother – not just Chan’s mother, who had difficulty accepting that her daughter was a lesbian, but also the relationship to the mother tongue (Chinese) and the mother country (Hong Kong). Fencing terms are used for structure. I was impressed by how clearly Chan sees how others perceive her, and by how generously she imagines herself into her mother’s experience. I’ve read 3.5 of the 4 nominees now and this is my pick to win the Costa Award.

Flèche by Mary Jean Chan: Exquisite poems of love and longing, with the speaker’s loyalties always split between head and heart, flesh and spirit. Over it all presides the figure of a mother – not just Chan’s mother, who had difficulty accepting that her daughter was a lesbian, but also the relationship to the mother tongue (Chinese) and the mother country (Hong Kong). Fencing terms are used for structure. I was impressed by how clearly Chan sees how others perceive her, and by how generously she imagines herself into her mother’s experience. I’ve read 3.5 of the 4 nominees now and this is my pick to win the Costa Award.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection.

Two favorites for me were “Formerly Feral,” in which a 13-year-old girl acquires a wolf as a stepsister and increasingly starts to resemble her; and the final, title story, a post-apocalyptic one in which a man and a pregnant woman are alone in a fishing boat, floating above a drowned world and living as if outside of time. This one is really rather terrifying. I also liked “Cassandra After,” in which a dead girlfriend comes back – it reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I’m currently reading for #MARM. “Stop Your Women’s Ears with Wax,” about a girl group experiencing Beatles-level fandom on a tour of the UK, felt like the odd one out to me in this collection. Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

Sherwood alternates between Eva’s quest and a recreation of József’s time in wartorn Europe. Cleverly, she renders the past sections more immediate by writing them in the present tense, whereas Eva’s first-person narrative is in the past tense. Although József escaped the worst of the Holocaust by being sentenced to forced labor instead of going to a concentration camp, his brother László and their friend Zuzka were in Theresienstadt, so readers get a more complete picture of the Jewish experience at the time. All three wind up in the Lake District after the war, rebuilding their lives and making decisions that will affect future generations.

My inclination is to adapt one of Italo Calvino’s definitions of a classic (recapped

My inclination is to adapt one of Italo Calvino’s definitions of a classic (recapped

In

In  Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly, which I

Mary Ann Sate, Imbecile by Alice Jolly, which I  John Steinbeck’s

John Steinbeck’s

I’ve always felt that Maggie O’Farrell expertly straddles the line between literary and women’s fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny. Her best is The Hand that First Held Mine, but everything I’ve read by her is wonderful. I’d happily read more books like hers. (Expectation by Anna Hope was slightly less successful.)

I’ve always felt that Maggie O’Farrell expertly straddles the line between literary and women’s fiction; her books are addictively readable but also hold up to critical scrutiny. Her best is The Hand that First Held Mine, but everything I’ve read by her is wonderful. I’d happily read more books like hers. (Expectation by Anna Hope was slightly less successful.)