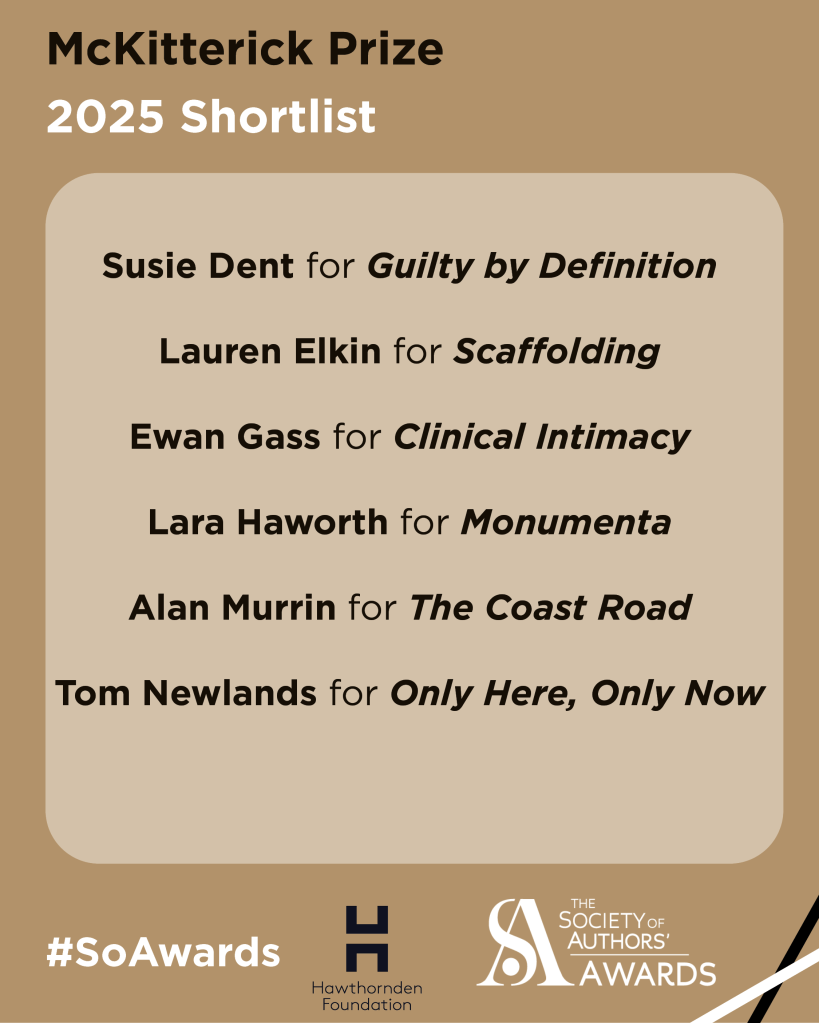

The 2025 McKitterick Prize Shortlist

For the fourth year in a row, I’ve been involved in judging the McKitterick Prize (for a first novel, published or unpublished, by a writer over 40). However, after three years of helping to assess the unpublished manuscripts, this was my first time as a judge for the published submissions. It has been a great experience! Today the shortlists for all of the 2025 Society of Authors Awards have been announced, so I can share our finalists below.

My three fellow judges and I were all asked for 50-word blurbs about each book and about the shortlist as a whole. I’m honoured that my overall blurb was chosen to accompany the McKitterick rundown in the press release:

Each of these six novels has a fully realized style. So confident and inviting are they that it’s hard to believe they are debuts. With nuanced characters and authentic settings and dilemmas, they engage the mind and delight the emotions. I will be following these authors’ careers with keen interest.

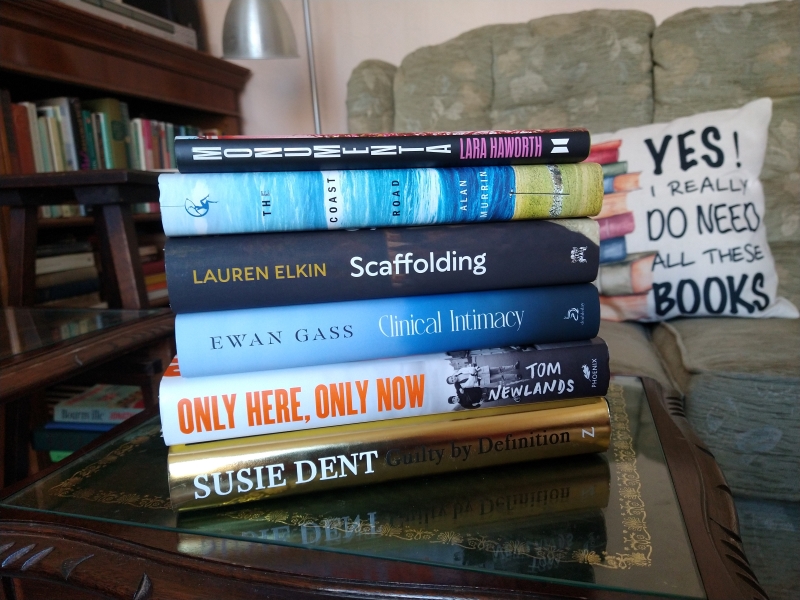

Notably, Tom Newlands’s Only Here, Only Now is a finalist for two of the prizes this year, the other being the ACDI Literary Prize, which is awarded to “a disabled or chronically ill writer, for an outstanding novel containing a disabled or chronically ill character or characters.” (A worthy successor to the Barbellion Prize, which, unfortunately, only ran for three years, 2020–22.) His teenage protagonist grows up in working-class Scotland in the 1990s with undiagnosed ADHD.

The winner and runner-up will be announced in advance of the SoA Awards ceremony in London on 18 June. In previous years, I have stayed home and watched the livestream, but this year I’ll attend in person and hope to meet Southwark Cathedral’s resident cat, Hodge!

Have you read anything from the McKitterick shortlist, or one of the other prize lists?

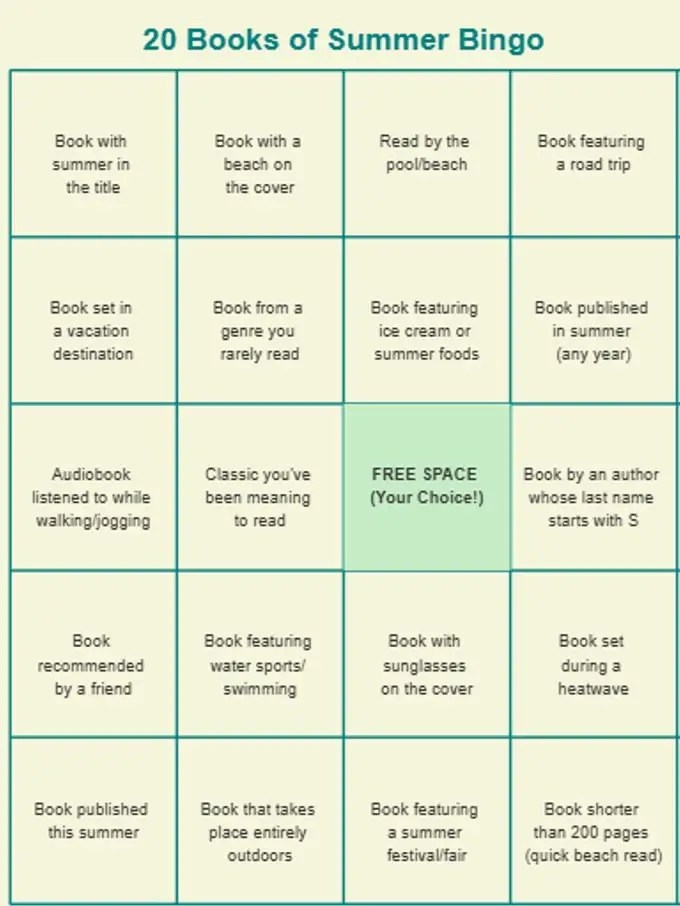

20 Books of Summer 2025 Plans

It’s my eighth year participating in the 20 Books of Summer challenge, this year co-hosted by Annabel and Emma after Cathy stepped down. #20BooksofSummer2025 starts on 1 June and runs through 31 August. In some previous years I have chosen a theme, even something as simple as “books by women.” Last year I combined two criteria and managed to get through 20 hardback books I owned by women. The problem with setting even simple boundaries like that is that I seem to almost immediately lose interest. Even more dangerous to pick 20 specific books, lest I go off them right away. Nonetheless, that’s what I’ve done. Expect substitutions galore, however; most years I read only half (or less) of what I’ve earmarked.

My only firm rule is that all 20 books must be from my own shelves. Ideally, they wouldn’t overlap with my usual reviewing commitments, book club reads, or other themed challenges (e.g., June: Reading the Meow, Father’s Day, Scotland holiday; August: Women in Translation), though it would be no problem if they did. I’m the only one enforcing this!

Other themed June reading options.

I like to work towards multiple goals, so I’ve chosen five books each in four categories.

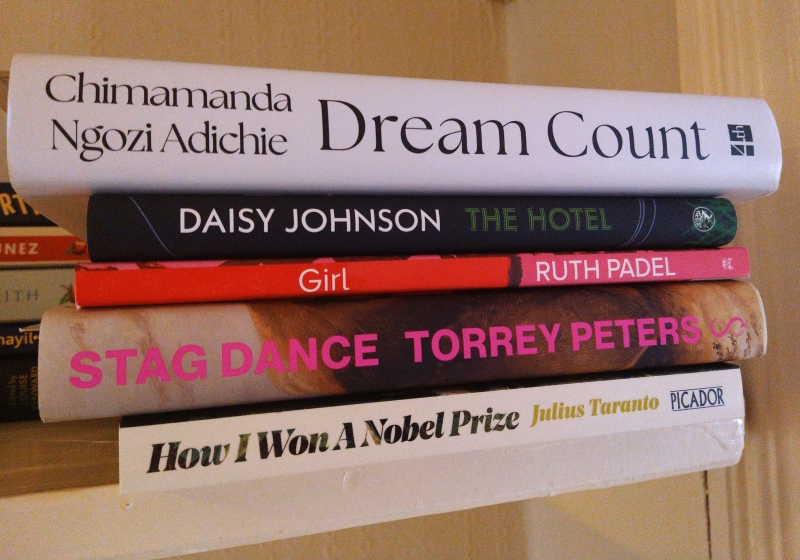

Books I acquired new this year:

Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Hungerford Bookshop) – I pre-ordered this, a super-rarity for me, and read the first 20-some pages before petering out. I think it’s fair to say it won’t be a favourite of hers for me, but I’d still like to read it in its publication year.

The Hotel by Daisy Johnson (Hungerford Bookshop with Christmas gift token) – Creepy short stories by an author whose long-form fiction I’ve really enjoyed. Also counts toward my low-key goal of reducing the list of authors by whom I own two or more unread books.

Girl by Ruth Padel (Hungerford Bookshop with Christmas gift token) – A poetry collection about girlhood through history and in myth. A repeat appearance on my summer reading list; I reviewed her Emerald in 2021. Good to add it in for variety, and a quick win length-wise.

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters (Bookshop.org) – I bought this to show solidarity with trans women after a short-sighted legal ruling here in the UK. Detransition, Baby was awesome but I haven’t managed to get into this yet. It contains three long short stories plus a novella.

How I Won a Nobel Prize by Julius Taranto (Hungerford Bookshop with Christmas gift token) – I believe it was Susan’s review that put this on my radar, though the title and the fact that it’s an academic satire would have been enough to get it onto my TBR.

Catch-up review copies:

A couple of these date back to 2023…

Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino – “At the moment when Voyager 1 is launched into space … , a baby of unusual perception is born to a single mother in Philadelphia. Adina Giorno … recognizes that she is different: She possesses knowledge of a faraway planet. The arrival of a fax machine enables her to contact her extraterrestrial relatives.” Quirky; well received by blog and Goodreads friends.

The Sleep Watcher by Rowan Hisayo Buchanan – I’ve read her other two novels but for some reason didn’t pick this up when it was first sent to me. “When she is sixteen, Kit suffers a summer of sleeplessness that isn’t quite what it seems; her body lies in bed while she wanders through her family home, the streets of her run-down seaside town and into the houses of friends and strangers.” Bonus points for being set during summer.

Museum Visits by Éric Chevillard – My one selection in translation. This hybrid collection of short pieces might be deemed essays or stories. “This ensemble of comic miniatures compiles reflections on chairs, stairs, stones, goldfish, objects found, strangers observed, scenarios imagined, reasonable premises taken to absurd conclusions, and vice versa.”

Storm Pegs by Jen Hadfield – New in paperback. I knew I had to read a Shetland-set memoir, and had enjoyed Hadfield’s piece in the Antlers of Water anthology. “In prose as rich and magical as Shetland itself, Hadfield transports us to the islands as a local; introducing us to the remote and beautiful archipelago where she has made her home”.

The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese – Cutting for Stone is brilliant but I was daunted by the even greater heft of this follow-up. I hope I’ll find just the right time to sink into it. “Spanning the years 1900 to 1977,” set “on India’s Malabar Coast, and follows three generations of a family that suffers a peculiar affliction: in every generation, at least one person dies by drowning—and in Kerala, water is everywhere.”

Summer-themed books / four in a row on the Bingo card:

I’d be aiming to complete the second row with this quartet:

(Book set in a vacation destination)

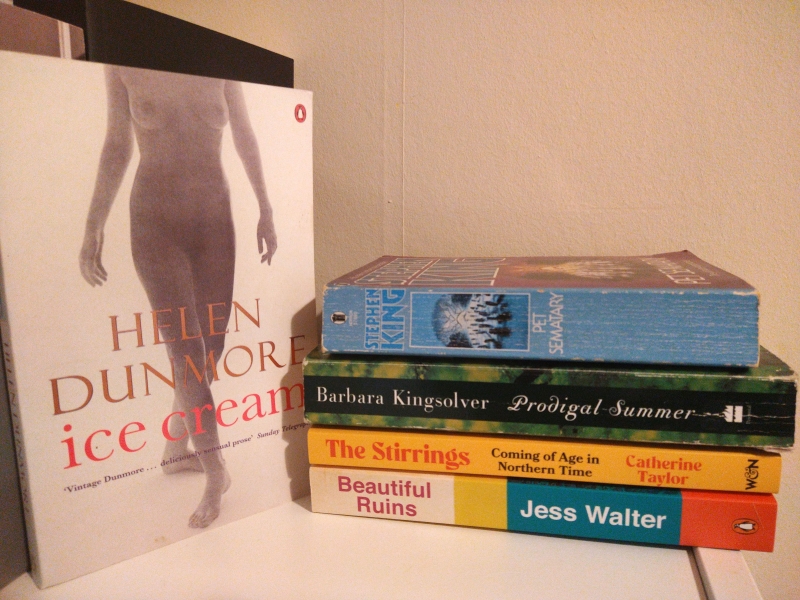

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (40th birthday gift from my husband, purchased from Hungerford Bookshop) – “the story of an almost-love affair that begins on the Italian coast in 1962 and resurfaces fifty years later in Hollywood. From the lavish set of Cleopatra to the shabby revelry of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival to the backlots of contemporary Hollywood, this is a dazzling, yet deeply human roller coaster of a novel.”

(Book from a genre you rarely read)

Pet Sematary by Stephen King (Little Free Library) – I’ve only ever read King’s book on writing, which of course is not representative of his oeuvre. Sounds like this could be a good introduction to his horror work. Rural Maine + dead animals in the woods + grief theme. A chunky but lightweight paperback; I fancy it for my solo train ride home from Edinburgh.

(Book featuring ice cream or summer foods)

Ice Cream by Helen Dunmore (Community Furniture Project) – A short story collection, facing out because the spine is faded to illegibility rather than to show off the naked lady. I’ve enjoyed Dunmore’s stories before (Love of Fat Men). The plots are described as “ranging from … the death of a lighthouse keeper’s wife to the birth of babies from the Superstock catalogue.”

(Book published in summer)

The Stirrings by Catherine Taylor (Bookshop.org with Christmas gift token) – This was originally published in August 2023, and it’s also set mostly during two pivotal summers: “the scorching summer of 1976 – the last Catherine Taylor would spend with both her parents in their home in Sheffield” and “1989’s ‘Second Summer of Love’, a time of sexual awakening for Catherine, and the unforeseen consequences that followed it.”

Plus my one reread of the challenge:

Prodigal Summer by Barbara Kingsolver (Little Free Library) – “From her outpost in an isolated mountain cabin, Deanna Wolfe, a reclusive wildlife biologist, watches a den of coyotes that have recently migrated into the region. She is caught off-guard by a young hunter who invades her most private spaces and confounds her self-assured, solitary life.”

I have a number of other potential summery reads, too.

“Just because” books

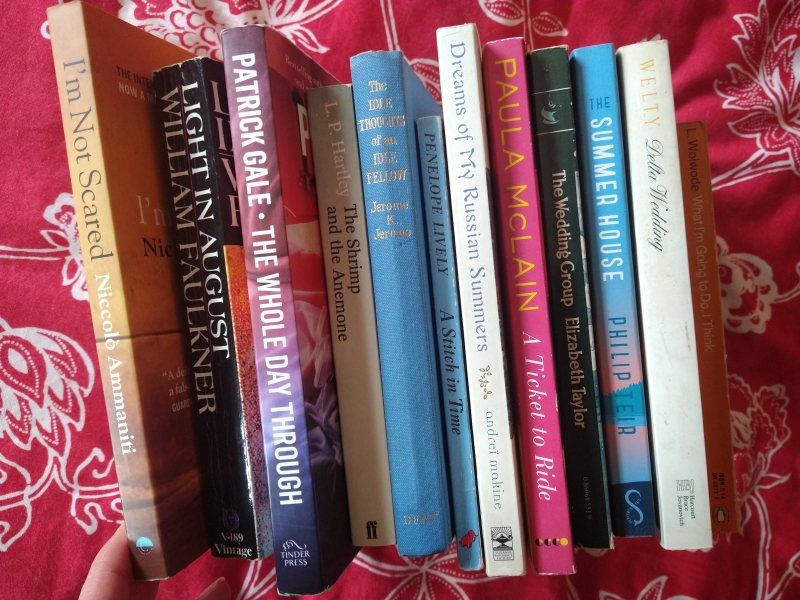

At the start of the year, I pulled out two huge piles of books I had no particular excuse to read yet was keen to get to. My plan was to pick up one per week or so. Of course, I’ve not so much as opened one yet. Three of these are from that stack, with two more from my BIPOC shelf.

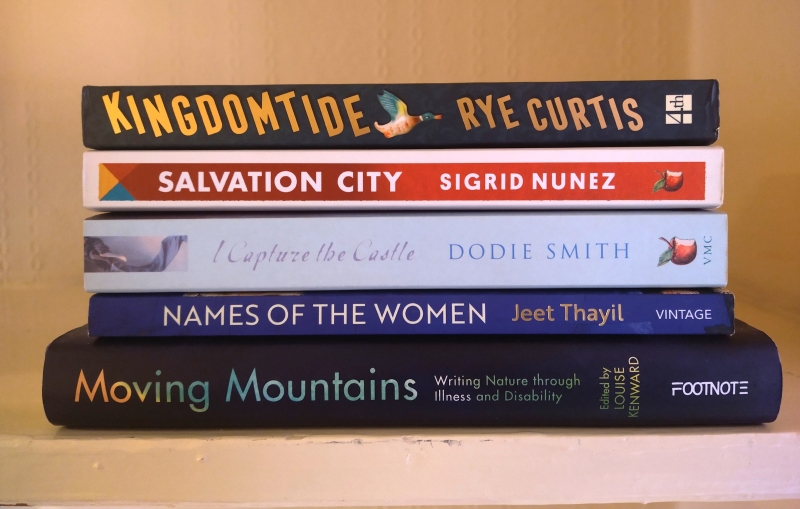

Kingdomtide by Rye Curtis (passed on by Laura T. – thank you!) – I’ve meant to read this for ages, plus it sounds like a good readalike for Heartwood. “The sole survivor of a plane crash, seventy-two-year-old Cloris Waldrip finds herself lost and alone in the unforgiving wilderness of Montana’s rugged Bitterroot Range … Intertwined with her story is Debra Lewis, a park ranger struggling with addiction, a recent divorce, and a new mission: to find and rescue Cloris.”

Salvation City by Sigrid Nunez (new from Amazon some years back) – I love Nunez and aim to read all of her books. This sounds very different from the four I know! “His family’s sole survivor after a flu pandemic …, Cole Vining is lucky to have found refuge with the evangelical Pastor Wyatt and his wife in a small town in southern Indiana. As the world outside has grown increasingly anarchic, Salvation City has been spared much of the devastation, and its residents have renewed their preparations for the Rapture.”

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith (charity shop, possibly a decade ago?) – One I’ve always meant to read. My token classic for this challenge, though there are plenty more to choose from on the bookcase in the lounge, e.g. an Austen for Brona’s #ReadAusten25 challenge. “Through six turbulent months of 1934, 17-year-old Cassandra Mortmain keeps a journal, filling three notebooks with sharply funny yet poignant entries about her home, a ruined Suffolk castle, and her eccentric and penniless family.”

Names of the Women by Jeet Thayil (gift from my wish list several years ago) – A novella on the stack will be welcome; this is “about the women whose roles were suppressed, reduced or erased in the Gospels. … Together, the voices of the women dare us to reimagine the story of the New Testament in a way it has never before been told.”

Moving Mountains, ed. Louise Kenward (gift from my wish list last year) – “A first-of-its-kind anthology of nature writing by authors living with chronic illness and physical disability. Through 25 pieces, the writers … offer a vision of nature that encompasses the close up, the microscopic, and the vast.” It will be nice to have a book of short nature pieces on the go.

The above list is more fiction-heavy than usual for me, with a number of chunksters – but also four short fiction collections and a poetry collection to balance out the length. Inspired by Eleanor, I decided to ensure at least 25% were by authors of colour.

If I need to draw on back-ups, I have many more between my “just because” stack, my Women’s Prize nominees shelf, and the rest of my BIPOC authors area.

This happens to be my 1,500th blog post!!

What do you make of my lists? See any options that I should prioritize instead?

April Releases by Chung, Ellis, Gaige, Lutz, McAlpine and Rubin

April felt like a crowded publishing month, though May looks to be twice as busy again. Adding this batch to my existing responses to books by Jean Hannah Edelstein & Emily Jungmin Yoon plus Richard Scott, I reviewed nine April releases. Today I’m featuring a real mix of books by women, starting with two foodie family memoirs, moving through a suspenseful novel about a lost hiker, a sparse Scandinavian novella, and a lovely poetry collection with themes of nature and family, and finishing up with a collection of aphorisms. I challenged myself to write just a paragraph on each for simplicity and readability.

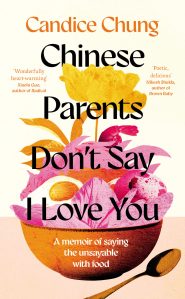

Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You: A memoir of saying the unsayable with food by Candice Chung

“to love is to gamble, sometimes gastrointestinally … The stomach is a simple animal. But how do we settle the heart—a flailing, skittish thing?”

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

I got Caroline Eden (Cold Kitchen) and Nina Mingya Powles (Tiny Moons) vibes from this vibrant essay collection spotlighting food and family. The focus is on 2019–2021, a time of huge changes for Chung. She’s from Hong Kong via Australia, and reconnects with her semi-estranged parents by taking them along on restaurant review gigs for a Sydney newspaper. Fresh from a 13-year relationship with “the psychic reader,” she starts dating again and quickly falls in deep with “the geographer.” Sharing meals in restaurants and at home kindles closeness and keeps their spirits up after Covid restrictions descend. But when he gets a job offer in Scotland, they have to make decisions about their relationship sooner than intended. Although there is a chronological through line, the essays range in time and style, including second-person advice column (“Faux Pas”) and choose-your-own adventure (“Self-Help Meal”) segments alongside lists, message threads and quotes from the likes of Deborah Levy. My favourite piece was “The Soup at the End of the Universe.” Chung delicately contrasts past and present, singleness and being partnered, and different mental health states. The essays meld to capture a life in transition and the tastes and bonds that don’t alter.

With thanks to Elliott & Thompson for the free copy for review.

Chopping Onions on My Heart: On Losing and Preserving Culture by Samantha Ellis

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

Ellis was distressed to learn that her refugee parents’ first language, Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, is in danger of extinction. Her own knowledge of it is piecemeal, mostly confined to its colourful food-inspired sayings – for example, living “eeyam al babenjan (in the days of the aubergines)” means that everything feels febrile and topsy-turvy. She recounts her family’s history with conflict and displacement, takes a Zoom language class, and ponders what words, dishes, and objects she would save on an imaginary “ark” that she hopes to bequeath to her son. Along the way, she reveals surprising facts about Ashkenazi domination of the Jewish narrative. “Did you know the poet [Siegfried Sassoon] was an Iraqi Jew?” His great-grandfather even invented a special variety of mango pickle. All of the foods described sound delicious, and some recipes are given. Ellis’s writing is enthusiastic and she braids the book’s various strands effectively. I wasn’t as interested in the niche history as I wanted to be, but I did appreciate learning about an endangered culture and language.

With thanks to Chatto & Windus (Vintage/Penguin) for the proof copy for review.

Heartwood by Amity Gaige

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

This was on my Most Anticipated list after how much I’d enjoyed Sea Wife when we read it for Literary Wives club. In July 2022, 42-year-old nurse Valerie Gillis, nicknamed “Sparrow,” goes missing in the Maine woods while hiking the Appalachian Trail. An increasingly desperate search ensues as the chances of finding her alive diminish with each day. The shifting formats – letters, transcripts, news reports, tip line messages – hold the interest. However, the chapters voiced by Lt. Bev, the warden who heads the mission, are much the most engaging, and it’s a shame that her delightful interactions with her sisters and nieces are so few and come so late. The third-person passages about Lena Kucharski in her Connecticut retirement home are intriguing but somehow feel like they belong in a different book. Gaige attempts to bring the threads together through three mother–daughter pairs, which struck me as heavy-handed. Mostly, this hits the sweet spot between mystery and literary fiction (apart from some red herrings), but because I wasn’t particularly invested in the characters, even Valerie, this fell a little short of my expectations. (Read via Edelweiss)

Wild Boar by Hannah Lutz (2016; 2025)

[Translated from Swedish by Andy Turner]

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

“I have seen them, the wild boar, they have found their way into my dreams!” Ritve travels from Finland to the forests of southern Sweden to track the creatures. Glenn, who appraises project applications for the council, has boar wander onto his property in the middle of the night. Mia, recipient of a council grant for her Recollections of a Sigga Child proposal, brings her ailing grandfather to record his memories for the local sound archive. As midsummer approaches, these three characters plus a couple of their partners will have encounters with the boar and with each other. Short sections alternate between their first-person perspectives. There is a strong sense of place and how migration poses challenges for both the human and more-than-human worlds. But it’s over before it begins. I found myself frustrated by how little happens, how stingily the characters reveal themselves, and how the boar, ultimately, are no more than a metaphor or plot device – a frequent complaint of mine when animals are central to a narrative. This might appeal to fans of Melissa Harrison’s fiction. In any case, I congratulate The Emma Press on their first novel, which won an English PEN Award.

With thanks to The Emma Press for the free copy for review.

Small Pointed Things by Erica McAlpine

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

McAlpine is an associate professor of English at Oxford. Her second poetry collection is full of flora and fauna imagery. The title phrase comes from the opening poem, “Bats and Swallows” – in the “gloaming,” it’s hard to tell the difference between the flying creatures. The verse is bursting with alliteration and end rhymes, as just this first one shows (emphasis mine): “we couldn’t see / from where we stood in soft shadows / any signs that they were swallows // or bats”; “One seemed almost iridescent / as I tried to track / its crescent / flight across the hill.” Other poems consider moths, manatees, bees, swans and ladybirds; snowdrops and a cedar tree. Part II expands the view through conversations, theories and travel. What-ifs, consequences and regrets seep in. Parts III and IV incorporate mythical allusions, elegies and the concerns of motherhood. Sometimes the rhyme scheme adheres to a particular form. For instance, I loved “Triolet on My Mother’s 74th Birthday” – “You cannot imagine one season in another. … You cannot imagine life without your mother.” This is just my sort of poetry, sweet on the ear and rooted in nature and the everyday. A sample poem:

“Clementines”

New Year’s Day – another turning

of the sphere, with all we planned

in yesteryear as close to hand

as last night’s coals left unmanned

in the fire, still orange and burning.

It is the season for clementines

and citrus from Seville

and whatever brightness carries us until

leaves and petals once more fill

the treetops and the vines.

If ever you were to confess

some cold truth about love’s

dwindling, now would be the time – less

in order for things to improve

than for the half-bitter happiness

of peeling rinds

during mid-winter

recalling days that are behind

us and doors we cannot re-enter

and other doors we couldn’t find.

With thanks to Carcanet Press for the advanced e-copy for review.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for Our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Rubin is one of the best self-help authors out there: Her books are practical, well-researched and genuinely helpful. She understands human nature and targets her strategies to suit different personality types. If you know her work, you’re likely aware of her fondness for aphorisms. “Sometimes, a single sentence can provide all the insight we need,” she believes. Here she collects her own pithy sayings relating to happiness, self-knowledge, relationships, work, creativity and decision-making. Some of the aphorisms were familiar to me through her previous books or her social media. They’re straightforward and sensible, distilling down to a few words truths we might be aware of but hadn’t truly absorbed. Like the great aphorists throughout history, Rubin relishes alliteration, repetition and contrasts. Some examples:

Accept yourself, and expect more from yourself.

I admire nature, and I am also nature. I resent traffic, and I am also traffic.

Work is the play of adulthood. If we’re not failing, we’re not trying hard enough.

Don’t wait until you have more free time. You may never have more free time.

This is not as meaty as her other work, and some parts feel redundant, but that’s the nature of the project. It would make a good bedside book for nibbles of inspiration. (Read via Edelweiss)

Which of these appeal to you?

Carol Shields Prize Reads: Pale Shadows & All Fours

Later this evening, the Carol Shields Prize will be announced at a ceremony in Chicago. I’ve managed to read two more books from the shortlist: a sweet, delicate story about the women who guarded Emily Dickinson’s poems until their posthumous publication; and a sui generis work of autofiction that has become so much a part of popular culture that it hardly needs an introduction. Different as they are, they have themes of women’s achievements, creativity and desire in common – and so I would be happy to see either as the winner (more so than Liars, the other one I’ve read, even though that addresses similar issues). Both: ![]()

Pale Shadows by Dominique Fortier (2022; 2024)

[Translated from French by Rhonda Mullins]

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

This is technically a sequel to Paper Houses, which is about Emily Dickinson, but I had no trouble reading this before its predecessor. In an Author’s Note at the end, Fortier explains how, during the first Covid summer, she was stalled on multiple fiction projects and realized that all she wanted was to return to Amherst, Massachusetts – even though her subject was now dead. The poet’s presence and language haunt the novel as the characters (which include the author) wrestle over her words. The central quartet comprises Lavinia, Emily’s sister; Susan, their brother Austin’s wife; Mabel, Austin’s mistress; and Millicent, Mabel’s young daughter. Mabel is to assist with editing the higgledy-piggledy folder of handwritten poems into a volume fit for publication. Thomas Higginson’s clear aim is to tame the poetry through standardized punctuation, assigned titles, and thematic groupings. But the women are determined to let Emily’s unruly genius shine through.

The short novel rotates through perspectives as the four collide and retreat. Susan and Millicent connect over books. Mabel considers this project her own chance at immortality. At age 54, Lavinia discovers that she’s no longer content with baking pies and embarks on a surprising love affair. And Millicent perceives and channels Emily’s ghost. The writing is gorgeous, full of snow metaphors and the sorts of images that turn up in Dickinson’s poetry. It’s a lovely tribute that mingles past and present in a subtle meditation on love and legacy.

Some favourite lines:

“Emily never writes about any one thing or from any one place; she writes from alongside love, from behind death, from inside the bird.”

“Maybe this is how you live a hundred lives without shattering everything; maybe it is by living in a hundred different texts. One life per poem.”

“What Mabel senses and Higginson still refuses to see is that Emily only ever wrote half a poem; the other half belongs to the reader, it is the voice that rises up in each person as a response. And it takes these two voices, the living and the dead, to make the poem whole.”

With thanks to The Carol Shields Prize Foundation for the free e-copy for review.

All Fours by Miranda July (2024)

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

Miranda July’s The First Bad Man is one of the first books I ever reviewed on this blog back in 2015, after an unsolicited review copy came my way. It was so bizarre that I didn’t plan to ever read anything else by her, but I was drawn in by the hype machine and started this on my Kindle in September, later switching to a library copy when I got stuck at 65%. The narrator sets off on a road trip from Los Angeles to New York to prove to her husband, Harris, that she’s a Driver, not a Parker. But after 20 minutes she pulls off the highway and ends up at a roadside motel. She blows $20,000 on having her motel room decorated in the utmost luxury and falls for Davey, a younger man who works for a local car rental chain – and happens to be married to the decorator. In his free time, he’s a break dancer, so the narrator decides to choreograph a stunning dance to prove her love and capture his attention.

I got bogged down in the ridiculous details of the first two-thirds, as well as in the kinky stuff that goes on (with Davey, because neither of them is willing to technically cheat on a spouse; then with the women partners the narrator has after she and Harris decide on an open marriage). However, all throughout I had been highlighting profound lines; the novel is full to bursting with them (“maybe the road split between: a life spent longing vs. a life that was continually surprising”). I started to appreciate the story more when I thought of it as archetypal processing of women’s life experiences, including birth trauma, motherhood and perimenopause, and as an allegory for attaining an openness of outlook. What looks like an ending (of career, marriage, sexuality, etc.) doesn’t have to be.

Whereas July’s debut felt quirky for the sake of it, showing off with its deadpan raunchiness, I feel that here she is utterly in earnest. And, weird as the book may be, it works. It’s struck a chord with legions, especially middle-aged women. I remember seeing a Guardian headline about women who ditched their lives after reading All Fours. I don’t think I’ll follow suit, but I will recommend you read it and rethink what you want from life. It’s also on this year’s Women’s Prize shortlist. I suspect it’s too divisive to win either, but it certainly would be an edgy choice. (NetGalley/Public library)

(My full thoughts on both longlists are here.) The other two books on the Carol Shields Prize shortlist are River East, River West by Aube Rey Lescure and Code Noir by Canisia Lubrin, about which I know very little. In its first two years, the Prize was awarded to women of South Asian extraction. Somehow, I can’t see the jury choosing one of three white women when it could be a Black woman (Lubrin) instead. However, Liars and All Fours feel particularly zeitgeist-y. I would be disappointed if the former won because of its bitter tone, though Manguso is an undeniable talent. Pale Shadows? Pure literary loveliness, if evanescent. But honouring a translation would make a statement, too. I’ll find out in the morning!

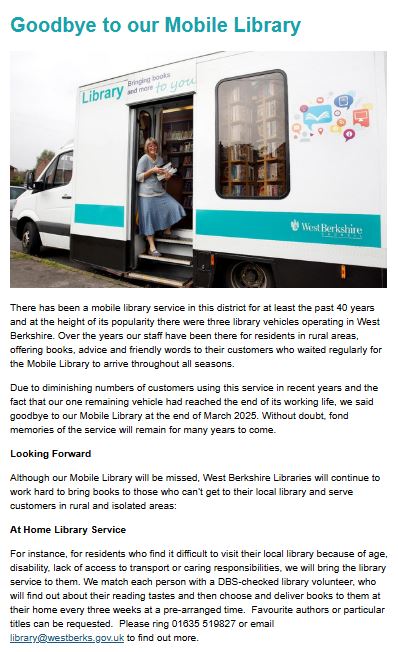

Love Your Library, April 2025

Thanks to Eleanor, Laura, Marcie, and Skai for posting about their recent library reading!

Sadly, my library system’s Mobile Library service closed down recently.

New at the library, however, is a digital piano, which can only be played with headphones on.

I was delighted to come across Lucy Mangan’s paean to Bromley Library in Bookish: “it was ugly as sin. Unlike my beloved Torridon, it was modern. Its cold, stark, straight lines, metal bookshelves and thin polyester carpeting … amplified every sound. … But it had more books than Torridon. Lots more books. More books in one place than I had ever seen. … And it had a secret. Behind a set of unassuming double doors was hiding a silent reading room and a reference library.” It was a sacred space for her even when she wasn’t borrowing books.

I was delighted to come across Lucy Mangan’s paean to Bromley Library in Bookish: “it was ugly as sin. Unlike my beloved Torridon, it was modern. Its cold, stark, straight lines, metal bookshelves and thin polyester carpeting … amplified every sound. … But it had more books than Torridon. Lots more books. More books in one place than I had ever seen. … And it had a secret. Behind a set of unassuming double doors was hiding a silent reading room and a reference library.” It was a sacred space for her even when she wasn’t borrowing books.

My library use over the last month:

(links are to books not already reviewed on the blog)

READ

- The Things He Carried by Stephen Cottrell (from my church’s theological library)

- Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton

- Broken Country by Clare Leslie Hall

- We Do Not Part by Han Kang

- Bookish: How Reading Shapes Our Lives by Lucy Mangan

- Poetry Unbound by Pádraig Ó Tuama

- The Leopard in My House: One Man’s Adventures in Cancerland by Mark Steel

SKIMMED

- The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

CURRENTLY READING

- Spring Is the Only Season: How It Works, What It Does and Why It Matters by Simon Barnes

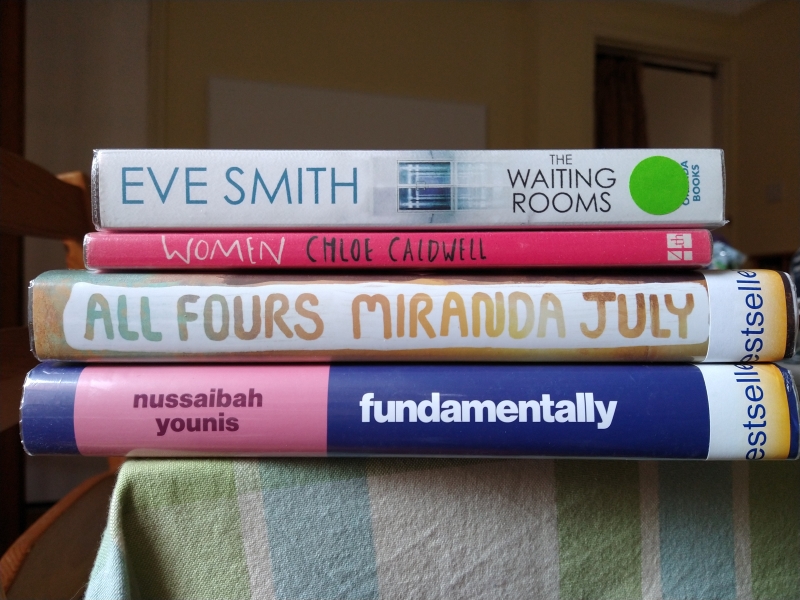

- Women by Chloe Caldwell

- All Fours by Miranda July

- Stoner by John Williams (a reread for May book club)

CHECKED OUT, TO BE READ

- Case Histories by Kate Atkinson (for June book club)

- A Conversation with a Cat by Hilaire Belloc

- Day by Michael Cunningham

- The Meteorites: Encounters with Outer Space and Deep Time by Helen Gordon

- Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working for You by Maisie Hill

- I Am Not a Tourist by Daisy J. Hung

- The Forgotten Sense: The Nose and the Perception of Smell by Jonas Olofsson

- The Waiting Rooms by Eve Smith

ON HOLD, TO BE PICKED UP

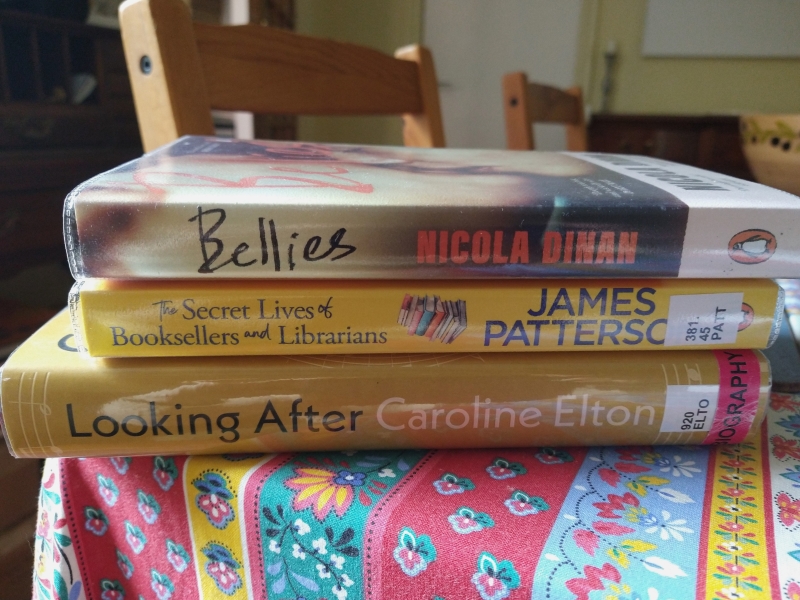

- Bellies by Nicola Dinan

- Looking After: A Portrait of My Autistic Brother by Caroline Elton

- Rebel Bodies: A Guide to the Gender Health Gap Revolution by Sarah Graham

- Of Thorn & Briar: A Year with the West Country Hedgelayer by Paul Lamb

- The Secret Lives of Booksellers and Librarians: True Stories of the Magic of Reading by James Patterson & Matt Eversmann

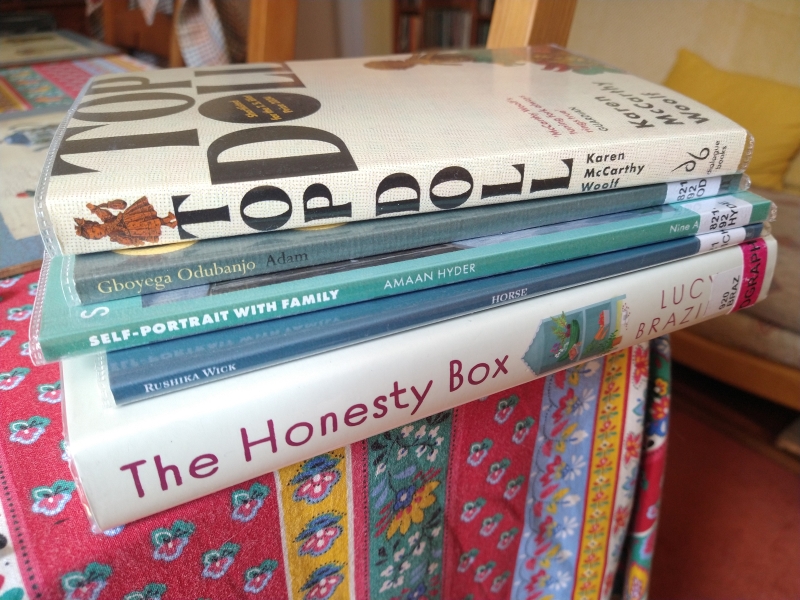

IN THE RESERVATION QUEUE

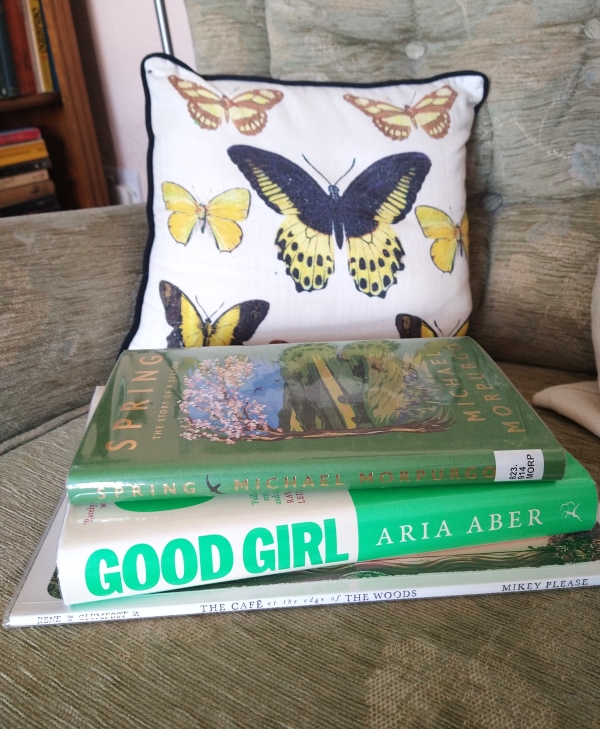

- Good Girl by Aria Aber

- Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever: A New Generation’s Search for Religion by Lamorna Ash

- A Sharp Scratch by Heather Darwent

- The Husbands by Holly Gramazio

- Normally Weird and Weirdly Normal: My Adventures in Neurodiversity by Robin Ince

- The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce

- Enchanted Ground: Growing Roots in a Broken World by Steven Lovatt

- Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane

- Whisky Galore by Compton Mackenzie

- The Persians by Sanam Mahloudji

- Spring: The Story of a Season by Michael Morpurgo

- Ripeness by Sarah Moss

- The Age of Diagnosis: Sickness, Health and Why Medicine Has Gone Too Far by Suzanne O’Sullivan

RETURNED UNFINISHED

- The Alternatives by Caoilinn Hughes – The type is so small in the paperback that I couldn’t cope. I will have to get this on Kindle or secondhand in hardback sometime.

- Fundamentally by Nussaibah Younis – The first couple of short chapters were entertaining enough but a little bit try-hard. I decided to focus on other things.

RETURNED UNREAD

- Deep Cuts by Holly Brickley – The first pages weren’t gripping and it was requested after me. Let me know if it’s worth trying again another time.

- Sarn Helen by Tom Bullough – It’s at least the second time I’ve had this out from the library, thinking it would be a perfect one to take on holiday to Wales, and not read it. I glanced at the first few pages but, you know, I don’t actually enjoy most long-distance walking adventure books.

What have you been reading or reviewing from the library recently?

Share a link to your own post in the comments. Feel free to use the above image. The hashtag is #LoveYourLibrary.

#1952Club: Patricia Highsmith, Paul Tillich & E.B. White

Simon and Karen’s classics reading weeks are always a great excuse to pick up some older books. I assembled an unlikely trio of lesbian romance, niche theology, and an animal-lover’s children’s classic.

Carol by Patricia Highsmith

Originally published as The Price of Salt under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, this is widely considered the first lesbian novel with a happy ending (it’s more open-ended, really, but certainly not tragic; suicide was a common consequence in earlier fiction). Therese, a 19-year-old aspiring stage designer in New York City, takes a job selling dolls in a department store one Christmas season. Her boyfriend, Richard, is a painter and has promised to take her to Europe, but she’s lukewarm about him and the physical side of their relationship has never interested her. One day, a beautiful blonde woman in a fur coat – “Mrs. H. F. Aird” (Carol) – comes to her counter to order a doll and have it sent to her out in New Jersey. Therese sends a Christmas card to the same address, and the women start meeting up for drinks and meals.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

It takes time for them to clarify their feelings to themselves, let alone to each other. “It would be almost like love, what she felt for Carol, except that Carol was a woman,” Therese thinks early on. When she first visits Carol’s home, a mothering dynamic prevails. Carol is going through a divorce and worries about its effect on her daughter, Rindy. The older woman tucks Therese into bed and brings her warm milk. Scenes like this have symbolic power but aren’t overdone; another has Therese and Richard out flying kites. She brings up homosexuality as a theoretical (“Did you ever hear of it? … I mean two people who fall in love suddenly with each other, out of the blue. Say two men or two girls”) and he cuts her kite strings.

The second half of the book has Carol and Therese setting out on a road trip out West. It should be an idyllic consummation, but they realize they’re being trailed by a private detective collecting evidence for Carol’s husband Harge to use against her in a custody battle. I was reminded of the hunt for Humbert Humbert and his charge in Lolita; “the whole world was ready to be their enemy,” Therese realizes, and to consider their relationship “sordid and pathological,” as Richard describes it in a letter.

The novel is a beautiful and subtle romance that unfolds despite the odds against it. I’d read five of Highsmith’s mysteries and thought them serviceable but nothing special (I don’t read crime in general). This does, however, share their psychological intensity and the suspense about how things will play out. Highsmith gives details about Therese’s early life and Carol’s previous intimate friendship that help to explain some things but never reduce either character to a diagnosis or a tendency. Neither of them wanted just anyone, some woman; it was this specific combination of souls that sparked at first sight. (Secondhand from a charity shop that closed long ago, so I know I’d had it on my shelf unread since 2016!) ![]()

The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

Tillich is a theologian who left Nazi Germany for the USA in 1933. I had to read selections from his work as part of my Religion degree (during the Pauline Theology tutorial I took in Oxford during my year abroad, I think). This book is based on a lecture series he delivered at Yale University. He posits that in an age of anxiety, which “becomes general if the accustomed structures of meaning, power, belief and order disintegrate” – certainly apt for today! – it is more important than ever to develop the courage to be oneself and to be “as a part.” The individual and the collective are of equal importance, then. Tillich discusses various philosophers and traditions, from the Stoics to Existentialism. I have to admit that I barely got anything out of this, I found it so jargon-filled, repetitive and elliptical. It’s been probably 15 years or more since I’ve read any proper theology. I adopted that old student skimming trick of reading the first paragraph of each chapter, followed by the topic sentence of each paragraph, but that left me mostly none the wiser. Anyway, I believe his conclusion is that, when assailed by doubt, we can rely on “the God above the God of theism” – by which I take it he means the ground of all being rather than the deity envisioned by any specific religious system. (University library)

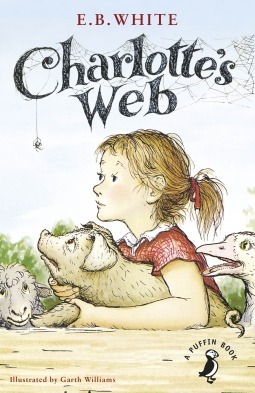

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

My library has a small section of the children’s department called “Family Matters” that includes the labels “First Time” (starting school, etc.), “Family” (divorce, new baby), “Health” (autism, medical conditions) and “Death.” I have the feeling Charlotte’s Web is not at all well known in the UK, whereas it’s a standard in the USA alongside L.M. Montgomery and Laura Ingalls Wilder. Were it more familiar to British children, it would be a great addition to that “Death” shelf. (Don’t read the Puffin Modern Classics introduction if you don’t want spoilers!) Wilbur is a doubly rescued pig. First, Fern Arable hand-rears him when he’s the doomed runt of the litter. When he’s transferred to Uncle Homer Zuckerman’s farm and an old sheep explains he’ll be fattened up for slaughter, his new friend Charlotte intervenes.

Charlotte is a fine specimen of a barn spider, well spoken and witty. She puts her mind to saving Wilbur’s bacon by weaving messages into her web, starting with “Some Pig.” He’s soon a county-wide spectacle, certain to survive the chop. But a farm is always, inevitably, a place of death. White fashions such memorable characters, including Templeton the gluttonous rat, and captures the hope of new life returning as the seasons turn over. Talking animals aren’t difficult to believe in when Fern can hear every word they say. The black-and-white line drawings are adorable. And making readers care about invertebrates? That’s a lasting achievement. I’m sure I read this several times as a child, but I appreciated it all the more as an adult. (Little Free Library) ![]()

I’ve previously participated in the 1920 Club, 1956 Club, 1936 Club, 1976 Club, 1954 Club, 1929 Club, 1940 Club, 1937 Club, and 1970 Club.

Poetry Month Reviews & Interview: Amy Gerstler, Richard Scott, Etc.

April is National Poetry Month in the USA, and I was delighted to have several of my reviews plus an interview featured in a special poetry issue of Shelf Awareness on Friday. I’ve also recently read Richard Scott’s second collection.

Wrong Winds by Ahmad Almallah

Palestinian poet Ahmad Almallah’s razor-sharp third collection bears witness to the devastation of Gaza.

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Through allusions, Almallah participates in an ancient lineage of poets, opening the collection with an homage to Al-Shanfarā and ending with “A Lament” for Zbigniew Herbert. Federico García Lorca is also a major influence. Occasional snippets of Arabic, French, and German, and accounts of travels in Berlin and Granada, reveal a cosmopolitan background. The speaker in “Loose Strings” considers exile, engaged in the potentially futile search for a homeland that is being destroyed: “What does it mean to be a poet, another ‘Homer’/ going home? Trying to find one?”

Tonally, anger and grief alternate, while alliteration and slant rhymes (sweat/sweet) create entrancing rhythms. In “Before Gaza, a Fall” and “My Tongue Is Tied Up Today,” staccato phrasing and spaced-out stanzas leave room for the unspeakable. The pièce de résistance is “A Holy Land, Wasted” (co-written with Huda Fakhreddine), which situates T.S. Eliot’s existential ruin in Palestine. Almallah contrasts Gaza then and now via childhood memories and adult experiences at checkpoints. His pastiche of “The Waste Land” starts off funny (“April is not that bad actually”) but quickly darkens, scorning those who turn away from tragedy: “It’s not good/ for your nerves to watch/ all that news, the sights/ of dead children.” The wordplay dazzles again here: “to motes the world crumbles, shattered/ like these useless mots.”

For Almallah, who now lives in Philadelphia, Gaza is elusive, enduringly potent—and mourned. Sometimes earnest, sometimes jaded, Wrong Winds is a remarkable memorial. ![]()

Is This My Final Form? by Amy Gerstler

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

Amy Gerstler’s exceptional book of poetry leaps from surrealism to elegy as it ponders life’s unpredictability.

The language of transformation is integrated throughout. Aging and the seasons are examples of everyday changes. “As Winter Sets In” delivers “every day/ a new face you can’t renounce or forsake.” “When I was a bird,” with its interspecies metamorphoses, introduces a more fantastical concept: “I once observed a scurry of squirrels,/ concealed in a hollow tree, wearing seventeenth/ century clothes. Alas, no one believes me.” Elsewhere, speakers fall in love with the bride of Frankenstein or turn to dinosaur urine for a wellness regimen.

The collection contains five thematic slices. Part I spotlights women behaving badly (such as “Marigold,” about a wild friend; and “Mae West Sonnet,” in an hourglass shape); Part II focuses on music and sound. The third section veers from the inherited grief of “Schmaltz Alert” to the miniplay “Siren Island,” a tragicomic Shakespearean pastiche. Part IV spins elegies for lives and works cut short. The final subset includes a tongue-in-cheek account of pandemic lockdown activities (“The Cure”) and wry advice for coping (“Wound Care Instructions”).

Monologues and sonnets recur—the title’s “form” refers to poetic structures as much as to personal identity. Alliteration plus internal and end rhymes create satisfying resonance. In the closing poem, “Night Herons,” nature puts life into perspective: “the whir of wings/ real or imagined/ blurs trivial things.”

This delightfully odd collection amazes with its range of voices and techniques.

I also had the chance to interview Amy Gerstler, whose work was new to me. (I’ll certainly be reading more!) We chatted about animals, poetic forms and tone, Covid, the Los Angeles fires, and women behaving ‘badly’. ![]()

Little Mercy by Robin Walter

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

In Robin Walter’s refined debut collection, nature and language are saving graces.

Many of Walter’s poems are as economical as haiku. “Lilies” entrances with its brief lines, alliteration, and sibilance: “Come/ dark, white/ petals// pull/close// —small fists// of night—.” A poem’s title often leads directly into the text: “Here” continues “the body, yes,/ sometimes// a river—little/ mercy.” Vocabulary and imagery reverberate, as the blessings of morning sunshine and a snow-covered meadow salve an unquiet soul (“how often, really, I want/ to end my life”).

Frequent dashes suggest affinity with Emily Dickinson, whose trademark themes of loss, nature, and loneliness are ubiquitous here, too. Vistas of the American West are a backdrop for pronghorn antelope, timothy grass, and especially the wrens nesting in Walter’s porch. Animals are also seen in peril sometimes: the family dog her father kicked in anger or a roadkilled fox she encounters. Despite the occasional fragility of the natural world, the speaker is “held by” it and granted “kinship” with its creatures. (How appropriate, she writes, that her mother named her for a bird.)

The collection skillfully illustrates how language arises from nature (“while picking raspberries/ yesterday I wanted to hold in my head// the delicious names of the things I saw/ so as to fold them into a poem later”—a lovely internal rhyme) and becomes a memorial: “Here, on earth,/ we honor our dead// by holding their names/ gentle in our hollow mouths—.”

This poised, place-saturated collection illuminates life’s little mercies. ![]()

The three reviews above are posted with permission from Shelf Awareness.

That Broke into Shining Crystals by Richard Scott

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

I’ve never forgotten how powerful it was to hear Richard Scott read aloud from his forthcoming collection, Soho, at the Faber Spring Party in February 2018. Back then I called his work “amazingly intimate,” and that is true of this second collection as well.

It also mirrors his debut in that the book is in several discrete sections – like movements of a musical composition – and there are extended allusions to particular poets (there, Paul Verlaine and Walt Whitman; here, Andrew Marvell and Arthur Rimbaud). But there is one overall theme, and it’s a tough one: Scott’s boyhood grooming and molestation by a male adult, and how the trauma continues to affect him.

Part I contains 21 “Still Life” poems based on particular paintings, mostly by Dutch or French artists (see the Notes at the end for details). I preferred to read the poems blind so that I didn’t have the visual inspiration in my head. The imagery is startlingly erotic: the collection opens with “Like a foreskin being pulled back, the damask / reveals – pelvic bowl of pink-fringed shadow” (“Still Life with Rose”) and “Still Life with Bananas” starts “curved like dicks they sit – cosy in wicker – an orgy / of total yellowness – all plenty and arching – beyond / erect – a basketful of morning sex and sugar and sunlight”.

“O I should have been the / snail,” the poet laments; “Living phallus that can hide when threatened. But / I’m the oyster. … Cold jelly mess of a / boy shucked wide open.” The still life format allows him to freeze himself at particular moments of abuse or personal growth; “still” can refer to his passivity then as well as to his ongoing struggle with PTSD.

Part II, “Coy,” is what Scott calls a found poem or “vocabularyclept,” rearranging the words from Marvell’s 1681 “To His Coy Mistress” into 21 stanzas. The constraint means the phrases are not always grammatical, and the section as a whole is quite repetitive.

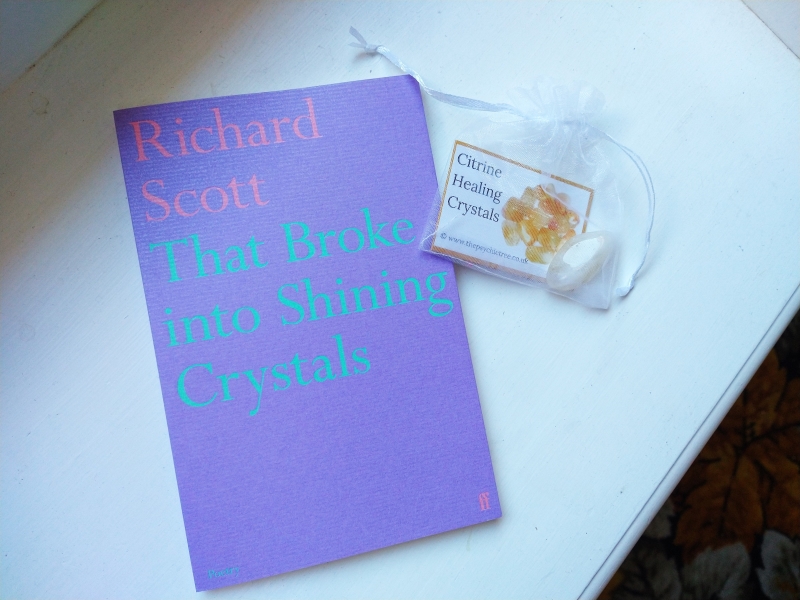

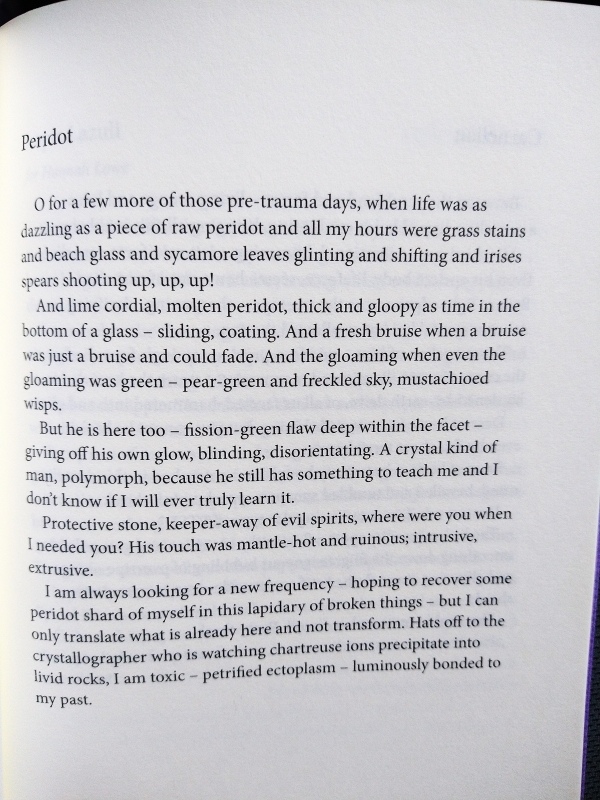

The title of the book (and of its final section) comes from Rimbaud and, according to the Notes, the 22 poems “all speak back to Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations but through the prism of various crystals and semi-precious stones – and their geological and healing properties.” My lack of familiarity with Rimbaud and his circle made me wonder if I was missing something, yet I thrilled to how visual the poems in this section were.

As with the Still Lifes, there’s an elevated vocabulary, forming a rich panoply of plants, creatures, stones, and colours. Alliteration features prominently throughout, as in “Citrine”: “O citrine – patron saint of the molested, sunny eliminator – crown us with your polychromatic glittering and awe-flecks. Offer abundance to those of us quarried. A boy is igneous.”

I’ve photographed “Peridot” (which was my mother’s birthstone) as an example of the before-and-after setup, the gorgeous language including alliteration, the rhetorical questioning, and the longing for lost innocence.

It was surprising to me that Scott refers to molestation and trauma so often by name, rather than being more elliptical – as poetry would allow. Though I admire this collection, my warmth towards it ebbed and flowed: I loved the first section; felt alienated by the second; and then found the third rather too much of a good thing. Perhaps encountering Part I or III as a chapbook would have been more effective. As it is, I didn’t feel the sections fully meshed, and the theme loses energy the more obsessively it’s repeated. Nonetheless, I’d recommend it to readers of Mark Doty, Andrew McMillan and Brandon Taylor. ![]()

Published today. With thanks to Faber for the free copy for review. An abridged version of this review first appeared in my Instagram post of 11 April.

Read any good poetry recently?

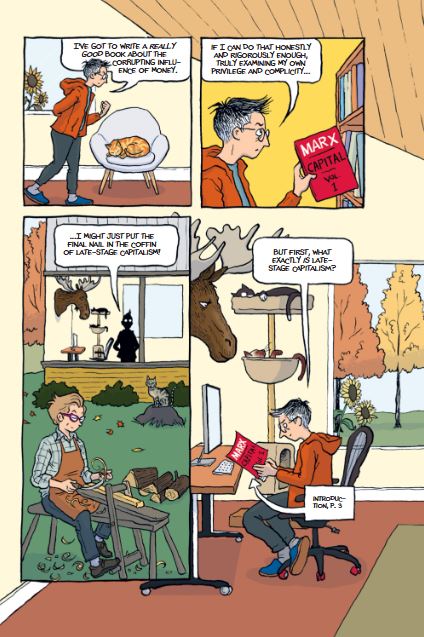

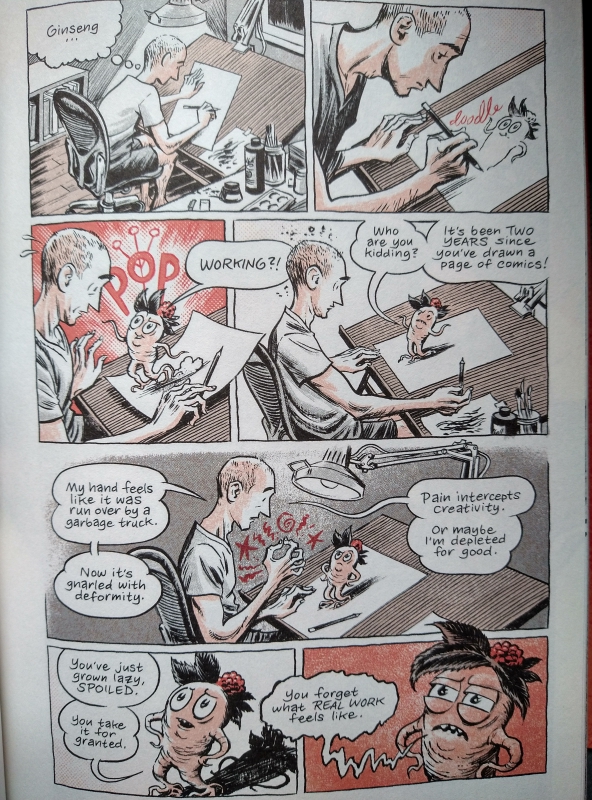

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

I’ve read all but one of Bechdel’s works now.

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

Nearly a decade ago, I reviewed Peter Kuper’s

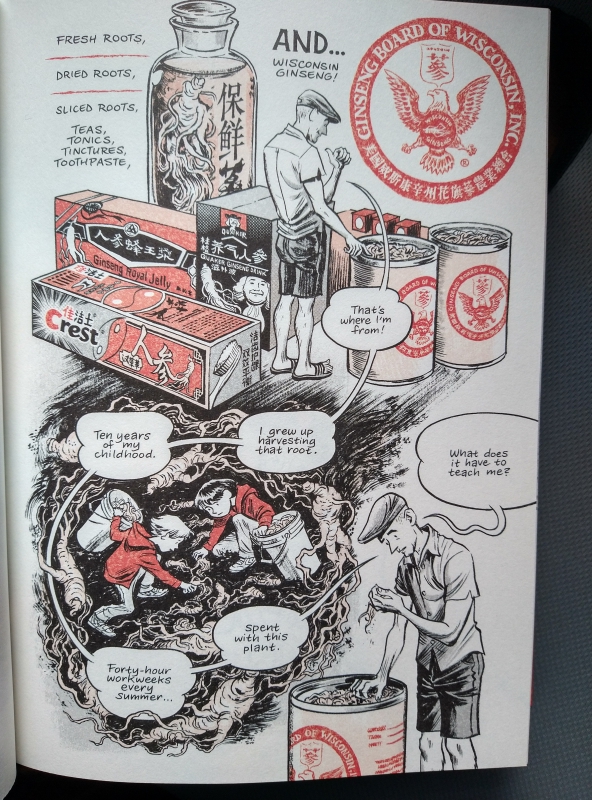

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

I’d read several of Thompson’s works and especially enjoyed his previous graphic memoir,

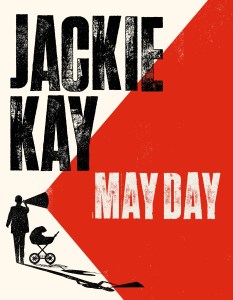

May Day is a traditional celebration for the first day of May, but it’s also a distress signal – as the megaphone and stark font on the cover reflect. Aptly, there are joyful verses as well as calls to arms here. Kay devotes poems to several of her role models, such as Harry Belafonte, Paul Robeson, Peggy Seeger and Nina Simone. But the real heroes of the book are her late parents, who were very politically active, standing up for workers’ rights and socialist values. Kay followed in their footsteps as a staunch attendee of protests. Her mother’s death during the Covid pandemic looms large. There is a touching triptych set on Mother’s Day in three consecutive years; even though her mum is gone for the last two, Kay still talks to her. Certain birds and songs will always remind her of her mum, and “Grief as Protest” links past and future. The bereavement theme resonated with me, but much of the rest made no mark (especially not the poems in dialect) and I don’t find much to admire poetically. I love Kay’s memoir, Red Dust Road, which has been among our most popular book club reads so far, but I’ve not particularly warmed to her poetry despite having read four collections now.

May Day is a traditional celebration for the first day of May, but it’s also a distress signal – as the megaphone and stark font on the cover reflect. Aptly, there are joyful verses as well as calls to arms here. Kay devotes poems to several of her role models, such as Harry Belafonte, Paul Robeson, Peggy Seeger and Nina Simone. But the real heroes of the book are her late parents, who were very politically active, standing up for workers’ rights and socialist values. Kay followed in their footsteps as a staunch attendee of protests. Her mother’s death during the Covid pandemic looms large. There is a touching triptych set on Mother’s Day in three consecutive years; even though her mum is gone for the last two, Kay still talks to her. Certain birds and songs will always remind her of her mum, and “Grief as Protest” links past and future. The bereavement theme resonated with me, but much of the rest made no mark (especially not the poems in dialect) and I don’t find much to admire poetically. I love Kay’s memoir, Red Dust Road, which has been among our most popular book club reads so far, but I’ve not particularly warmed to her poetry despite having read four collections now. I’d not read Morpurgo before. He’s known primarily as a children’s author; if you’ve heard of one of his works, it will likely be War Horse, which became a play and then a film. This is a small hardback, scarcely 150 pages and with not many words to a page, plus woodcut illustrations interspersed. As revered English nature authors such as John Lewis-Stempel and Richard Mabey have also done, he depicts a typical season through a diary of several months of life on his land. For nearly 50 years, his Devon farm has hosted the Farms for City Children charity he founded. He believes urban living cuts people off from the rhythm of the seasons and from nature generally; “For so many reasons, for our wellbeing, for the planet, we need to revive that connection.” Now in his eighties, he lives with his wife in a small cottage and leaves much of the day-to-day work like lambing to others. But he still loves observing farm tasks and spotting wildlife (notably, an otter and a kingfisher) on his walks. This is a pleasant but inconsequential book. I most appreciated how it captures the feeling of seasonal anticipation – wondering when the weather will turn, when that first swallow will return.

I’d not read Morpurgo before. He’s known primarily as a children’s author; if you’ve heard of one of his works, it will likely be War Horse, which became a play and then a film. This is a small hardback, scarcely 150 pages and with not many words to a page, plus woodcut illustrations interspersed. As revered English nature authors such as John Lewis-Stempel and Richard Mabey have also done, he depicts a typical season through a diary of several months of life on his land. For nearly 50 years, his Devon farm has hosted the Farms for City Children charity he founded. He believes urban living cuts people off from the rhythm of the seasons and from nature generally; “For so many reasons, for our wellbeing, for the planet, we need to revive that connection.” Now in his eighties, he lives with his wife in a small cottage and leaves much of the day-to-day work like lambing to others. But he still loves observing farm tasks and spotting wildlife (notably, an otter and a kingfisher) on his walks. This is a pleasant but inconsequential book. I most appreciated how it captures the feeling of seasonal anticipation – wondering when the weather will turn, when that first swallow will return. This 400+-page tome has an impressive scope. Like Mark Cocker does in

This 400+-page tome has an impressive scope. Like Mark Cocker does in

I appreciated this quote from Women by Chloe Caldwell, whose narrator works in a library: “Books are like doctors and I am lucky to have unlimited access to them during this time. A perk of the library.” Bibliotherapy works!

I appreciated this quote from Women by Chloe Caldwell, whose narrator works in a library: “Books are like doctors and I am lucky to have unlimited access to them during this time. A perk of the library.” Bibliotherapy works!